In this chapter, you will learn about . . .

Procurement

E-Procurement

Distribution

Transportation

The Global Supply Chain

Web resources for this chapter include

Internet Exercises

Online Practice Quizzes

Lecture Slides in PowerPoint

Virtual Tours

Company and Resource Weblinks

www.wiley.com/college/russell

Global Supply Chain Procurement and Distribution AT HERSHEY'S

Hershey's global supply chain starts in the jungles of countries like Brazil, Indonesia, the Ivory Coast, and Ghana, where the cacao tree grows. The cacao tree's melon-like fruit is harvested by hand and inside the fruit are about 20 to 40 seeds, or cocoa beans. These beans ferment in large piles for about a week and are then dried. The beans are used to produce cocoa products including cocoa liquor, cocoa butter, and cocoa powder, which are the most significant raw materials Hershey's uses to produce its chocolate products. Hershey's purchases these cocoa products directly from third-party suppliers that source cocoa beans in Far Eastern, West African, and South American equatorial regions. West African accounts for approximately 70% of the world's supply of cocoa beans. Hershey's also procures other raw materials like milk, sugar, and nut products from suppliers in the United States and around the world. Hershey's primary manufacturing and distribution facilities are in the states, but it also manufactures, imports, markets, and sells products in Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and India. It also has a manufacturing agreement with another company to produce products for its Asian market, particularly China. Starting in 2007 Hershey's initiated a three-year global supply chain transformation project at a cost of $600 million that, when completed, will enhance Hershey's manufacturing, sourcing, and customer service capabilities, and reduce inventories resulting in improvements in working capital and generate significant resources to invest in various growth initiatives. The transformed supply chain program will significantly increase manufacturing capacity utilization by reducing the number of production lines by more than one-third, outsourcing production of low value-added items, and constructing a flexible, cost-effective production facility in Monterrey, Mexico, to meet emerging marketplace needs.

In this chapter we will discuss how global companies like Hershey's manage supply chains that stretch around the world.

Source: Hershey's Web site at www.thehersheycompany.com

In Chapter 10 we introduced the topic of supply chain management and focused on the strategy and design of supply chains. We discussed the various aspects, components and implications of supply chain management in a broad context; more of a macro-view of supply chains. Early in Chapter 10 in Figure 10.3 we identified the primary processes related to supply chain management— the procurement of supply, production, and the distribution of products and services. In this chapter we are going to focus more closely on two of these processes—procurement and distribution, which also includes transportation; this entails a more micro-view of supply chains. We will begin with a discussion of procurement; the process of obtaining supply; the goods and services that are used in the production process (whether it be goods or services).

Supply chains begin with supply at the farthest upstream point in the supply chain, inevitably from raw materials, as was shown in Figure 10.1. Purchased materials have historically accounted for about half of U.S. manufacturing costs, and many manufacturers purchase over half of their parts. Companies want the materials, parts, and services necessary to produce their products to be delivered on time, to be of high quality, and to be low cost, which are the responsibility of their suppliers. If deliveries are late from suppliers, a company will be forced to keep large, costly inventories to keep their own products from being late to their customers. Thus, purchasing goods and services from suppliers, or procurement, plays a crucial role in supply chain management.

•Procurement: the purchase of goods and services from suppliers.

A key element in the development of a successful partnership between a company and a supplier is the establishment of linkages. The most important linkage is information flow; companies and suppliers must communicate—about product demand, about costs, about quality, and so on—in order to coordinate their activities. To facilitate communication and the sharing of information many companies use teams. Cross-enterprise teams coordinate processes between a company and its supplier. For example, suppliers may join a company in its product-design process as on-site suppliers do at Harley-Davidson. Instead of a company designing a product and then asking a supplier if it can provide the required part or a company trying to design a product around an existing part, the supplier works with the company in the design process to ensure the most effective design possible. This form of cooperation makes use of the expertise and talents of both parties. It also ensures that quality features will be designed into the product.

Cross-enterprise teams coordinate processes between a company and supplier.

•On-demand (direct-response) delivery: requires the supplier to deliver goods when demanded by the customer.

•Continuous replenishment: supplying orders in a short period of time according to a predetermined schedule.

In an attempt to minimize inventory levels, companies frequently require that their suppliers provide on-demand, also referred to as direct-response, delivery to support a just-in-time (JIT) or comparable inventory system. In continuous replenishment, a company shares real-time demand and inventory data with its suppliers, and goods and services are provided as they are needed. For the supplier, these forms of delivery often mean making more frequent, partial deliveries, instead of the large-batch orders suppliers have traditionally been used to filling. While large-batch orders are easier for the supplier to manage, and less costly, they increase the customer's inventory. They also reduce the customer's flexibility to deal with sudden market changes because of their large investment in inventory. Every part used at Honda's Marysville, Ohio, plant is delivered on a daily basis. Sometimes parts deliveries are required several times a day. This often requires that suppliers move their location to be close to their customer. For example, over 75% of the U.S. suppliers for Honda are within a 150-mile radius of their Marysville, Ohio, assembly plant. Each day grocers send Campbell's Soup Company demand and inventory data at their distribution centers via electronic data interchange (EDI), which Campbell's uses to replenish inventory of its products on a daily basis.

In addition to meeting their customers' demands for quality, lower inventory, and prompt delivery, suppliers are also expected to help their customers lower product cost by lowering the price of its goods and services. These customer demands on its suppliers—high quality, prompt delivery, and lower prices—are potentially very costly to suppliers. Prompt delivery of products and services as they are demanded from its customers may require the supplier to maintain excessive inventories itself. These demands require the supplier to improve its own processes and make its own supply chain more efficient. Suppliers require of their own suppliers what has been required of them— high quality, lower prices, process improvement, and better delivery performance.

•Sourcing: the selection of suppliers.

•Outsourcing: the purchase of goods and services from an outside supplier.

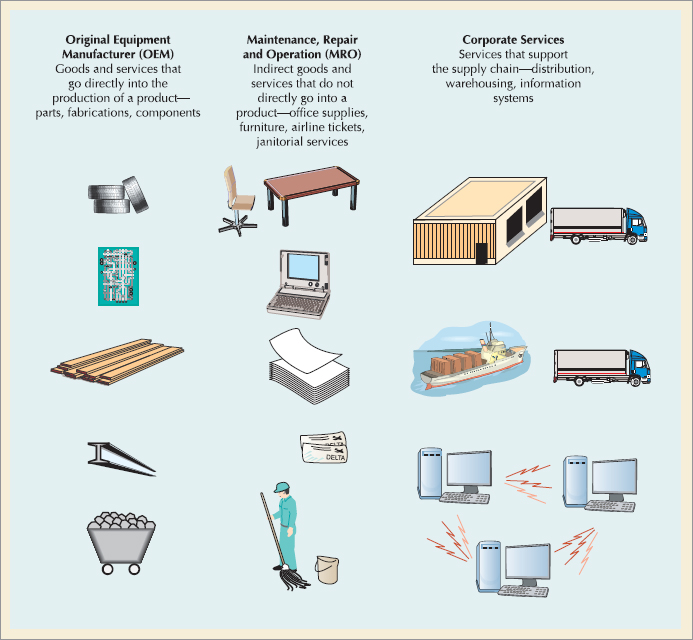

The selection of suppliers is called sourcing; suppliers are literally the "source" of supply. Outsourcing is the act of purchasing goods and services that were originally produced in-house from an out-side supplier. Outsourcing is nothing new; for decades companies have outsourced as a short-term solution to problems such as an unexpected increase in demand, breakdowns in plants and equipment, testing products, or a temporary lack of plant capacity. However, outsourcing has become a long-term strategic decision instead of simply a short-term tactical one. Companies, especially large, multinational companies, are moving more production, service, and inventory functions into the hands of suppliers. Figure 11.1 shows the three major categories of goods and services that companies tend to outsource.

• Core competencies: what a company does best.

Many companies are outsourcing as a strategic move so that they can focus more on their core competencies, that is, what they do best. They let a supplier do what the company is not very good at and what the supplier is most competent to do. Traditionally, many companies, especially large ones, attempted to own and operate all of their sources of supply and distribution along the supply chain so that they would have direct managerial control and reduce their dependence on potentially unreliable suppliers. They also thought it was more cost effective. However, this stretched these companies' resources thin, and they discovered they did not have the expertise to do everything well. In addition, management of unwieldy, complex supply chains was often difficult. Large inventories were kept throughout the supply chain to buffer against uncertainties and poor management practices. The recent trend toward outsourcing provides companies with greater flexibility and resources to focus on their own core competencies, and partnering relationships with suppliers provides them with control. In addition, many companies are outsourcing in countries where prices for supply are lower, such as China.

By limiting the numbers of its suppliers a company has more direct influence and control over the quality, cost, and delivery performance of a supplier if the company has a major portion of that supplier's volume of business. The company and supplier enter into a partnership in which the sup-plier agrees to meet the customer's quality standards for products and services and helps lower the customer's costs. The company can also stipulate delivery schedules from the supplier that enables them to reduce inventory. In return, the company enters into a long-term relationship with the supplier, providing the supplier with security and stability. It may seem that all the benefits of such an arrangement are with the customer, and that is basically true. The customer dictates cost, quality, and performance to the supplier. However, the supplier passes similar demands on to its own suppliers, and in this manner the entire supply chain can become more efficient and cost effective.

E-procurement is part of the business-to-business (B2B) commerce being conducted on the Internet, in which buyers make purchases directly from suppliers through their Web sites, by using soft-ware packages or through e-marketplaces, e-hubs, and trading exchanges. The Internet can streamline and speed up the purchase order and transaction process from companies. Benefits include lower transaction costs associated with purchasing, lower prices for goods and services, reduced labor (clerical) costs, and faster ordering and delivery times.

What do companies buy over the Internet? Purchases can be classified according to two broad categories: manufacturing inputs (direct products) and operating inputs (indirect products). Direct products are the raw materials and components that go directly into the production process of a product. Because they tend to be unique to a particular industry, they are usually purchased from in-dustry-specific suppliers and distributors. They also tend to require specialized delivery; UPS does not typically deliver engine blocks. Indirect products do not go directly into the production of finished goods. They are the maintenance, repair, and operation (MRO) goods and services we mentioned previously (Figure 11.1). They tend not to be industry specific; they include things like office supplies, computers, furniture, janitorial services, and airline tickets. As a result they can often be purchased from vendors like Staples, and they can be delivered by services like UPS.

•E-procurement: direct purchase from suppliers over the Internet.

Direct products go directly into the production process of a product; indirect products do not.

More companies tend to purchase indirect goods and services over the Internet than direct goods. One reason is that a company does not have to be as careful about indirect goods since they typically cost less than direct products and they do not directly affect the quality of the company's own final product. Companies that purchase direct goods over the Internet tend to do so through suppliers with whom they already have an established relationship.

E-marketplaces or e-hubs consolidate suppliers' goods and services at one Internet site like a catalogue. For example, e-hubs for MROs include consolidated catalogues from a wide array of suppliers that enable buyers to purchase low-value goods and services with relatively high transaction costs more cheaply and efficiently over the Internet. E-hubs for direct goods and services are similar in that they bring together groups of suppliers at a few easy-to-use Web sites.

E-marketplaces like Ariba provide a neutral ground on the Internet where companies can streamline supply chains and find new business partners. An e-marketplace also offers services such as online auctions where suppliers bid on order contracts, online product catalogues with multiple supplier listings that generate online purchase orders, and request-for-quote (RFQ) service through which buyers can submit an RFQ for their needs and users can respond.

•E-marketplaces: Web sites where companies and suppliers conduct business-to-business activities.

A process used by e-marketplaces for buyers to purchase items is the reverse auction. In a reverse auction, a company posts contracts for items it wants to purchase that suppliers can bid on. The auction is usually open for a specified time frame, and vendors can bid as often as they want in order to provide the lowest purchase price. When the auction is closed, the company can compare bids on the basis of purchase price, delivery time, and supplier reputation for quality. Some e-marketplaces restrict participation to vendors who have been previously screened or certified for reliability and product quality. Reverse auctions are not only used to purchase manufacturing items but they are also being used to purchase services. For example, transportation exchanges hold reverse auctions for carriers to bid on shipping contracts and for air travel.

•Reverse auction: a company posts orders on the Internet for suppliers to bid on.

Sometimes companies use reverse auctions to create price competition among the suppliers it does business with; other times companies simply go through a reverse auction only to determine the lowest price without any intention of awarding a contract. It only wants to determine a baseline price to use in negotiations with its regular supplier. Companies that award contracts to low bidders in auctions can later discover their purchases are delivered late or not at all, and are of poor quality. Suppliers are often able to see online their rank in the bidding process relative to other bidders (who are anonymous), which provides pricing information to them for the future.

Distribution encompasses all of the channels, processes, and functions, including warehousing and transportation, that a product passes through on its way to the final customer (end user). It is the actual movement of products and materials between locations. Distribution management involves managing the handling of materials and products at receiving docks, storing products and materials, packaging, and the shipment of orders. The focus of distribution, what it accomplishes, is referred to as order fulfillment. It is the process of ensuring on-time delivery of the customer's order.

Distribution and transportation are also often referred to as logistics. Logistics management in its broadest interpretation is similar to supply chain management. However, it is frequently more narrowly defined as being concerned with just transportation and distribution, in which case logistics is a subset of supply chain management. In this decade total U.S. business logistics is over $1 trillion.

•Order fulfillment: the process of ensuring on-time delivery of an order.

•Logistics: the transportation and distribution of goods and services.

Distribution is not simply a matter of moving products from point A to point B. The driving force behind distribution and transportation in today's highly competitive business environment is speed. One of the primary quality attributes on which companies compete is speed of service. Customers have gotten used to instant access to information, rapid Internet-based order transac-tions, and quick delivery of goods and services. As a result, walking next door to check on what's in the warehouse is not nearly fast enough when customers want to buy a product now and a company has to let them know if it's in stock. That demands real-time inventory information. Calling a trucking firm and asking it when it will have a truck in the vicinity to pick up a delivery is not nearly fast enough when a customer has come to expect delivery in a few days or overnight. That also requires real-time information about carrier location, schedules, and capacity. Thus, the key to distribution speed is information, as it has been in our discussion of other parts of the supply chain.

The most important factor in transportation and distribution is speed.

Distribution is a particularly important supply chain component for Internet companies like Amazon.com, whose supply chains consist almost entirely of supply and distribution. These companies have no production process; they simply sell and distribute products that they acquire from suppliers. They are not driven from the front end of the supply chain—the Web site—they are driven by distribution at the back end. Their success ultimately depends on the capability to ship each order when the customer needs or wants it.

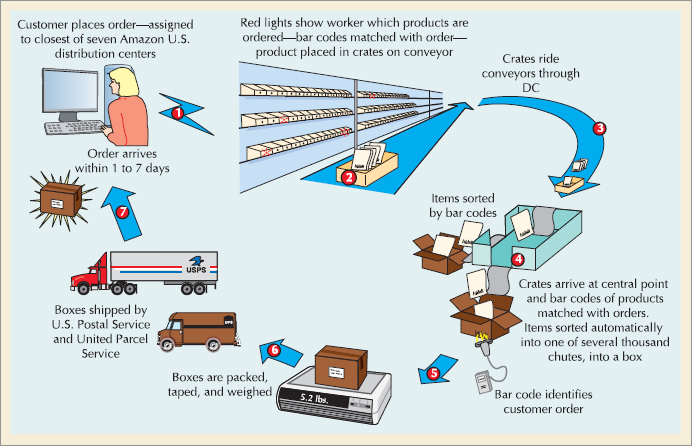

Figure 11.2 on the following page illustrates the order fulfillment process at Amazon.com when one of its millions of customers places an order via the Internet (or by phone). The order is transmitted to the closest distribution center where items are stored in a warehouse in shelved bins. Computers send workers to retrieve items from the shelves, and they place each item in a crate with other orders. When the crate is full it moves by conveyor through the plant to a central point. At this central sorting area bar codes are matched with order numbers to determine which items go with which order, and the items that fulfill an order are sorted into chutes. The items that make up an order are placed in a box as they come off the chute with a new bar code that identifies the order. The boxes are then packed, taped, weighed, and shipped by a carrier, for example, the U.S. Postal Service or UPS.

Distribution centers (DCs), which typically incorporate warehousing and storage, are buildings that are used to receive, handle, store, package, and then ship products. Some of the largest business facilities in the United States are di stribution centers. The UPS Worldwide Logistics warehouse in Louisville, Kentucky, includes 1.3 million square feet of floor space. Distribution centers for The Gap in Gallatin, Tennessee, Target in Augusta City, Virginia, and Home Depot in Savannah, Georgia, each encompass more than 1.4 million square feet of space—about 30 times bigger than the area of a football field, and about three-fourths the floor space of the Empire State Building.

As in other areas of supply chain management, information technology has a significant impact on distribution management. The Internet has altered how companies distribute goods by adding more frequent orders in smaller amounts and higher customer service expectations to the already difficult task of rapid response fulfillment. To fill Internet orders successfully, warehouses and distribution centers must be set up as "flow-through" facilities, using automated material-handling equipment to speed up the processing and delivery of orders.

Retailers have shifted from buying goods in bulk and storing them to pushing inventory and stor-age and final configuration back up the supply chain (upstream). They expect suppliers (and/or distributors) to make frequent deliveries of merchandise that includes a mix of different product items in small quantities (referred to as "mixed-pallet"), properly labeled, packed, and shipped in store-ready configurations. For example, some clothing retailers may want sweaters delivered already folded, ready for the store shelf, while others may want them to be on their own hangers. To adequately handle retailer requirements, distribution centers must be able to handle a variety of automated tasks.

Postponement, moves some final manufacturing steps like assembly or individual product customization into the warehouse or distribution center. Generic products or component parts (like computer components) are stored at the warehouse, and then final products are built-to-order (BTO), or personalized, to meet individual customer demand. It is a response to the adage that whoever can get the desired product to the customer first gets the sale. Postponement actually pulls distribution into the manufacturing process, allowing lead times to be reduced so that demand can be met more quickly. However, postponement also usually means that a distributor must stock a large number of inventory items at the warehouse to meet the final assembly or customization requirements; this can create higher inventory-carrying costs. The manufacturing and distribution supply chain members must therefore work together to synchronize their demand forecasts and carefully manage inventory.

•Postponement: moves some manufacturing steps into the distribution center.

•Warehouse management system (WMS): an automated system that runs the day-to-day operations of a distribution center.

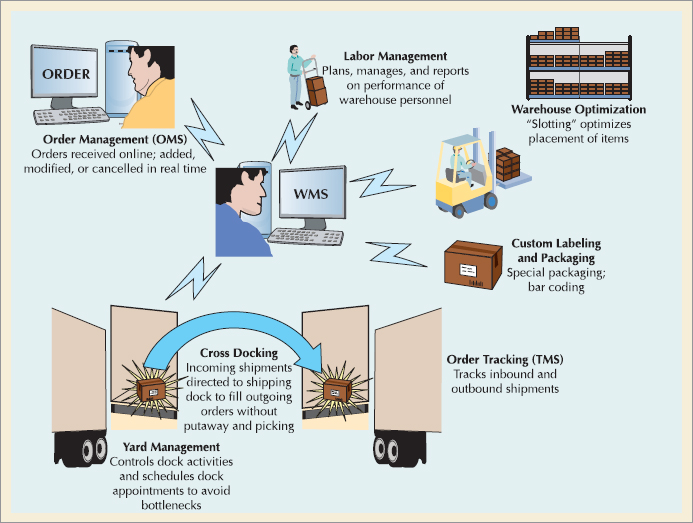

In order to handle the new trends and demands of distribution management, companies employ sophisticated, highly automated warehouse management systems (WMS) to run day-to-day operations of a distribution center and keep track of inventories. The WMS places an item in storage at a specific location (a putaway), locates and takes an item out of storage (a pick), packs the item, and ships it via a carrier. The WMS acknowledges that a product is available to ship, and, if it is not available, the system will determine from suppliers in real time when it will be available.

Figure 11.3 illustrates the features of a WMS. Orders flow into a WMS through an order management system (OMS). The OMS enables the distribution center to add, modify, or cancel orders in real time. When the OMS receives customer order information online, it provides a snapshot of product availability from the WMS and from suppliers via EDI. If an item is not in stock, the OMS looks into the supplier's production schedule to see when it will be available. The OMS then allocates inventory from the warehouse site to fill an order, establishes a delivery date, and passes these orders onto the transportation management system for delivery.

A WMS may include the following features: transportation management, order management, yard management, labor management, and warehouse optimization.

The transportation management system (TMS) allows the DC to track inbound and outbound shipments, to consolidate and build economical loads, and to select the best carrier based on cost and service. Yard management controls activities at the facility's dock and schedules dock appointments to reduce bottlenecks. Labor management plans, manages, and reports the performance level of warehouse personnel. Warehouse optimization optimizes the warehouse placement of items, called "slotting," based on demand, product groupings, and the physical characteristics of the item. A WMS also creates custom labeling and packaging. A WMS facilitates cross-docking, a system that Walmart originated which allows a DC to direct incoming shipments straight to a shipping dock to fill outgoing orders, eliminating costly putaway and picking operations. In a cross-docking system, products are delivered to a warehouse on a continual basis, where they are stored, repackaged, and distributed to stores without sitting in inventory. Goods "cross" from one loading dock to another, usually in 48 hours or less.

•Cross-docking: goods "cross" from one loading dock to another in 48 hours or less.

With vendor-managed inventory (VMI), manufacturers, instead of distributors or retailers, generate orders. Under VMI, manufacturers receive data electronically via EDI or the Internet about distributors' sales and stock levels. Manufacturers can see which items distributors carry, as well as several years of point-of-sale data, expected growth, promotions, new and lost business, and inventory goals, and use this information to create and maintain a forecast and an inventory plan. VMI is a form of "role reversal"—usually the buyer completes the administrative tasks of ordering; with VMI the responsibility for planning shifts to the manufacturer.

•Vendor-managed inventory (VMI): manufacturers rather than vendors generate orders.

VMI is usually an integral part of supply chain collaboration. The vendor has more control over the supply chain and the buyer is relieved of administrative tasks, thereby increasing supply chain efficiency. Both manufacturers and distributors benefit from increased processing speed, and fewer data entry errors occur because communications are through computer-to-computer EDI or the Internet. Distributors have fewer stockouts; planning and ordering costs go down because responsibility is shifted to manufacturers; and service is improved because distributors have the right product at the right time. Manufacturers benefit by receiving distributors' point-of-sale data, which makes forecasting easier.

Rival companies are also finding ways to collaborate in distribution. They have found that by pooling their distribution resources, which can create greater economies of scale, they can reduce their costs.

For example, Nabisco discovered it was paying for too many half-empty trucks so they moved to collaborative logistics. Using the Web as a central coordination tool between producers, carriers, and retailers, Nabisco can share trucks and warehouse space with other companies, even competitors, that are shipping to the same retail locations. Nabisco and other companies, including General Mills and Pillsbury, started using a collaborative logistics network from Nistevo Corporation. At Nistevo.com companies post the warehouse space they need or have available and share space, trucks, and ex-penses. The goal is that everyone, from suppliers to truckers to retailers, shares in the savings.

Another recent trend in distribution is outsourcing. Just as companies outsource to suppliers activities that they once performed themselves, producers and manufacturers are increasingly outsourcing distribution activities. The reason is basically the same for producers as it is for suppliers; outsourcing allows the company to focus on its core competencies. It also takes advantage of the expertise that distribution companies have developed. Outsourcing distribution activities tends to lower inventory levels and reduce costs for the outsourcing company.

Distribution outsourcing allows a company to focus on its core competencies and can lower inventory and reduce costs.

Nabisco Inc., with annual sales of $9 billion, delivers 500 types of cookies, more than 10,000 candies, and hundreds of other food items to 80,000 buyers and has incoming shipments of countless raw ingredients. It outsources many distribution and transportation activities to third-party logistics (3PL) companies. Outsourcing is more cost-effective and allows Nabisco to focus on core competencies.

In a supply chain, transportation is the movement of a product from one location to another as it makes its way to the end-use customer. Although supply chain experts agree that transportation tends to fall through the supply chain management cracks, receiving less attention than it should, it can be a significant supply chain cost. For some manufacturing companies, transportation costs can be as much as 20% of total production costs and run as high as 6% of revenue. For some retail companies primarily involved in the distribution of goods, like L.L. Bean and Amazon.com, transportation is not only a major cost of doing business, it is also a major determinant of prompt delivery service. L.L. Bean ships almost 16 million packages in a year—over 230,000 on its busiest day—mostly by UPS.

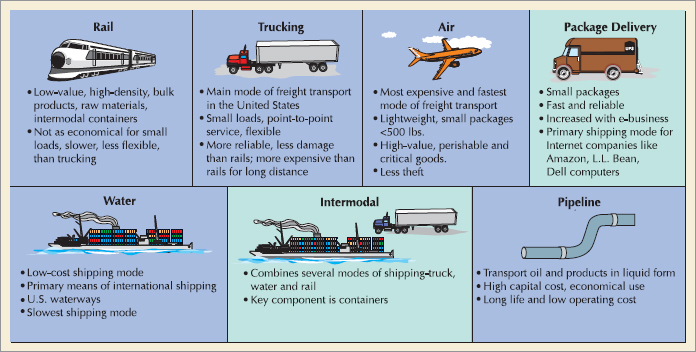

The principal modes of transportation within the United States are railroads, air, truck, inter-modal, water, package carriers, and pipeline. In the United States the greatest volume of freight is shipped by railroad (approximately one-third of the total), followed by trucking, pipeline, and in-land waterways. The different transport modes and some of their advantages and disadvantages are shown in Figure 11.4.

Railroads are cost effective for transporting low-value, high-density, bulk products such as raw materials, coal, minerals, and ores over long distances. Railroads operate on less flexible and slower schedules than trucks, and they usually cannot go directly from one business location to another as trucks can. Rail freight service has the worst record of quality performance of all modes of freight transport, with a higher incidence of product damage and almost 10 times more late deliveries than trucking.

Trucking is the main mode of freight transportation in the United States, generating over 75% of the nation's total freight cost each year. U.S. motor freight costs are over $500 billion annually. Trucks provide flexible point-to-point service, delivering small loads over short and long distances over widely dispersed geographic areas. Trucking service is typically more reliable and less damage-prone then railroads.

Air freight is the most expensive and fastest mode of freight transportation; it is also the fastest growing segment of the airline industry. For companies that use air freight, service is more important than price. Production stoppages because of missing parts or components, are much more expensive than the increased cost of air freight. For high-value goods such as pharmaceuticals, high technology, and consumer electronics, speed to market is important, and in addition, shorter shipping times reduce the chances for theft and other losses. The general rule for international air freight is that anything that's physically or economically perishable has to move by air instead of by ship. The major product groups that are shipped by international air freight, from largest to smallest, are perishables, construction and engineering equipment, textiles and wearing apparel, documents and small package shipments, and computers, peripherals, and spare parts.

Air freight is growing particularly fast in Asia and specifically China. The lack of ground infrastructure makes rail and trucking transport difficult between countries in Asia and regions in China. Companies with manufacturing plants in one place in Asia and suppliers in another are increasingly using air freight to connect the two.

Package carriers such as UPS, FedEx, and the U.S. Postal Service transport small packages, up to about 150 pounds. The growth of e-business has significantly increased the use of package carriers. Package carriers combine various modes of transportation, mostly air and truck, to ship small packages rapidly. They are not economical for large-volume shipments; however, they are fast and reliable, and they provide unique services that some companies must have. Package carriers have been innovative in the use of bar codes and the Internet to arrange and track shipments.

Federal Express Superhubs consolidate and distribute shipments from a central location. Federal Express is the industry leader in overnight package delivery service.

The FedEx Web site attracts more than 1 million hits per day, and it receives 70% of its customer orders electronically. FedEx delivers 7.5 million packages daily in over 220 countries.

Water transport over inland waterways, canals, the Great Lakes, and along coastlines is a slow but very low-cost form of shipping. It is limited to heavy, bulk items such as raw materials, minerals, ores, grains, chemicals, and petroleum products. If delivery speed is not a factor, water transport is cost competitive with railroads for shipping these kinds of bulk products. Water transport is the primary means of international shipping between countries separated by oceans for most products.

•Intermodal transportation: combines several modes of transportation to move shipments.

Intermodal transportation combines several modes of transportation to move shipments. The most common intermodal combination in the United States is truck–rail–truck, and the truck– water–rail/truck combination is the primary means of global transport. Intermodal transportation carries over 35% of all freight shipments over 500 miles in the United States. Intermodal truck–rail shipping can be as much as 40% cheaper than long-haul trucking.

The key component in intermodal transportation is the container. Within the United States containers are hauled as trailers attached to trucks to rail terminals, where they are double- or triple-stacked on railroad flatcars or specially designed "well cars," which feature a well-like lower section in which the trailer or container rides. The containers are then transported to another rail terminal, where they are reattached to trucks for direct delivery to the customer. For overseas shipments, container ships transport containers to ports where they are off-loaded to trucks or rail for transport. Around the world over 18 million containers make over 200 million trips each year, with over 25% originating from China alone.

Pipelines in the United States are used primarily for transporting oil and petroleum products. Pipelines called slurry lines carry other products such as coal and kaolin that have been pulverized and transformed into liquid form. Once the product arrives at its destination, the water is removed, leaving the solid material. Although pipelines require a high initial capital investment to construct, they are economical because they can carry materials over terrain that would be difficult for trucks or trains to travel across, for example, the Trans-Alaska pipeline. Once in place, pipelines have a long life and are low cost in terms of operation, maintenance, and labor.

One of the most popular forms of intermodal transportation uses containers that are transported via rail or truck to ports where they are loaded onto container ships for shipment overseas, and then loaded back onto trucks or rail at destination ports for delivery to end-use customers.

Internet transportation exchanges bring together shippers who post loads and carriers who post their available capacity in order to arrange shipments. In some exchanges once the parties have matched up at a Web site, all the negotiation is done offline. In others the online service manages the load matches automatically; the services match up shipments and carriers based on shipment characteristics, trailer availability, and the like. For example, shippers tender load characteristics, and the online service returns with recommendations on carrier price and service levels. Some services also provide an online international exchange structured as a reverse auction. The shippers will tender their loads, and carriers will bid on the shipment. Shipments remain up for bid until a shipper-specified auction closing time (like on e-Bay). However, the lowest price, or lowest bid, is not always conducive to quality service. At some sites the low bid does not necessarily win; the service takes into account quality issues such as transit time, the carrier, and availability in addition to price.

Two of the more well-known Internet exchange services are www.nte.com (National Transportation Exchange), and www.freightquote.com. At these sites (and others like it) shippers and carriers identify their available shipment or capacity needs and their business requirements. The exchanges automatically match compatible shippers with carriers based on price and service. Automated processes make the trade within a few hours with no phone calls, invoices, and so on.

A number of factors have combined to create a global marketplace. International trade barriers have fallen, and new trade agreements between countries and nations have been established. The dissolution of communism opened up new markets in Russia and Middle and Eastern Europe, and the creation of the European Community resulted in the world's largest economic market—400 million people. Europe, with a total population of 850 million is the largest, best-educated economic group in the world. Emerging markets in China, growing Asian export-driven economies, burgeoning global trading centers in Hong Kong and Singapore, and a newly robust economy in India have linked with the rest of the world to form a vigorous global economic community. Global trade now exceeds $25 trillion per year.

To compete globally requires an effective supply chain.

Globalization is no longer restricted to giant companies. Technology advances have made it possible for middle-tier companies to establish a global presence. Companies previously regional in scope are using the Internet to become global overnight. Information technology is the "enabler" that lets companies gain global visibility and link disparate locations, suppliers, and customers. However, many companies are learning that it takes more than a glitzy Web site to be a global player. As with the domestic U.S. market, it takes a well-planned and coordinated supply chain to be competitive and successful.

Moving products across international borders is like negotiating an intricate maze, riddled with potential pitfalls. For U.S. companies eager to enter new and growing markets, trading in foreign countries is not "business as usual." Global supply chain management, though global in nature, must still take into account national and regional differences. Customs, business practices, and regulations can vary widely from country to country and even within a country. Foreign markets are not homogeneous and often require customized service in terms of packaging and labeling. Quality can be a major challenge when dealing with Third World markets in countries with different languages and customers.

Some of the other major differences between domestic and global supply chain transactions include:

Increased documentation for invoices, cargo insurance, letters of credit, ocean bills of lading or air waybills, and inspections

Ever changing regulations that vary from country to country that govern the import and export of goods

Limited shipping modes

Differences in communication technology and availability

Different business practices as well as language barriers

Government codes and reporting requirements that vary from country to country

Numerous players, including forwarding agents, custom house brokers, financial institutions, insurance providers, multiple transportation carriers, and government agencies

Since 9/11, numerous security regulations and requirements

The proliferation of trade agreements has changed global markets and has accelerated global trade activity. Nations have joined together to form trading groups, also called nation groups, and customs unions, and within these groups products move freely with no import tax, called tariffs or duties, charged on member products. The members of a group charge uniform import duties to nations outside their group, thus removing tariff trade barriers within the group and raising barriers for outsiders. The group adopts rules and regulations for freely transporting goods across borders that, combined with reduced tariffs, give member nations a competitive advantage over nonmembers. These trade advantages among member nations lower supply chain costs and reduce cycle time—that is, the time required for products to move through the supply chain.

•Nation groups: nations joined together into trading groups.

•Tariffs (duties): taxes on imported goods.

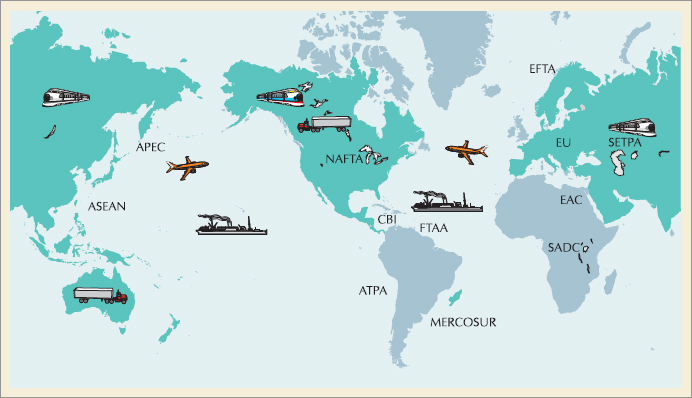

Figure 11.5 shows the international trade groups, or customs unions, that trade with the United States. NAFTA is the North American Free Trade Agreement, and EU is the European Community trade group, which includes many of the countries of Western Europe.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an international organization dealing with the global rules of trade. It ensures that trade flows as smoothly and freely as possible among its 146 members. The trade agreements and rules are negotiated and signed by governments, and their purpose is to help exporters and importers conduct business. Most-favored-nation trade (MFN) status is an arrangement in which WTO member countries must extend to other members the most favorable treatment given to any trading partner. For example, MFN status for China translates into lower duties on goods entering the United States, and fewer trade regulations for companies.

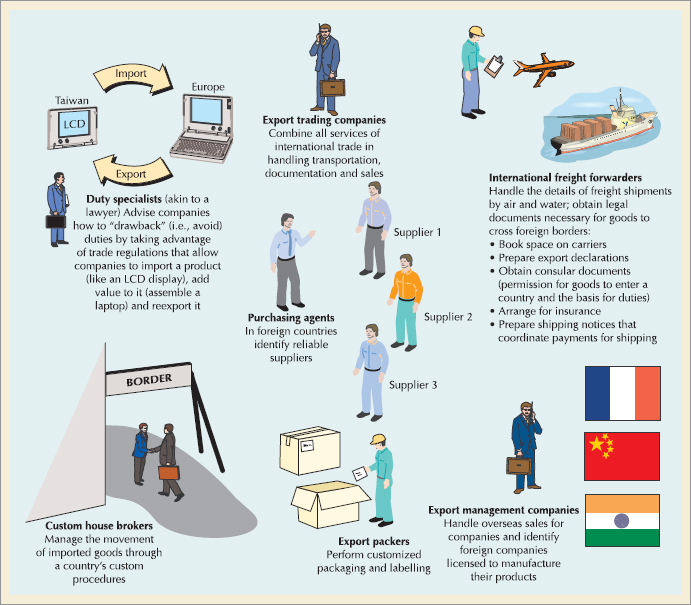

To overcome the obstacles and problems of global supply chain management, many companies hire one or more international trade specialists. Figure 11.6 summarizes the activities of the dif-ferent types of trade specialists.

In global trade landed cost is the total cost of producing, storing, and transporting a product to the site of consumption or another port. As many as 80 components can be included in landed cost; however, 85% of these components fall into two broad categories: (1) transportation cost and duty, and (2) governmental charges such as value added tax (VAT) and excise tax. Landed costs are important because the duty assessed by different governments incorporates varying portions of landed costs. For example, for U.S. imports, duty is charged free on board (FOB) the factory. This means that transportation costs from the point of entry into the United States to the factory destination are not calculated as part of the import duty charge. However, in other countries the duty assessed can include the cost of transportation from beginning to end.

•Trade specialists: include freight forwarders, customs house brokers, export packers, and export management and trading companies.

•Landed cost: the total cost of producing, storing, and transporting a product to its destination or port.

By knowing the landed cost of a product before it is purchased, a company can make more informed decisions, while poorly projected landed costs can balloon the price of a product move. Accurately estimating true landed costs helps avoid "clicker shock." Clicker shock occurs when an overseas customer places an order with a company that does not have the capability of calculating landed cost. Then the order gets shipped, and along the way tariffs get added on top—in some cases it can double the original purchase price.

•Value-added tax (VAT): an indirect tax assessed on the increase in value of a good at any stage of the production process from raw material to final product.

As we have indicated global supply chain management involves a stunningly complex matrix of language barriers, currency conversions, international trade agreements, taxes, tariffs, embargoes, duties, quotas, document requirements, local rules, and new trading partners. These factors require an automated, information technology solution for any company with any real volume of international shipments. International trade logistics (ITL) companies use Web-based software products that link directly to customers' Web sites to eliminate or reduce the obstacles to global trade. They convert language and currency from the U.S. system into those used by many of the United States's trading partners, giving potential buyers in other nations easy access to product and price information. ITL systems also provide information on tariffs, duties, and customs processes and some link with financial institutions to facilitate letters of credit and payment. Through the use of extensive databases these systems can attach the appropriate weights, measurements, and unit prices to individual products ordered over the Web. These systems can also incorporate transportation costs and conversion rates so that purchasers can electronically see the landed cost of ordering a product and having it delivered. Some ITL systems use a landed cost search engine that calculates shipping costs online while a company enters an order so it will know exactly what the costs will be in U.S. funds. They also track global shipments.

The Port of Singapore handles over 10 million TEUs (20-foot container equivalent units) annually at three container terminals. The Brani terminal has 9 berths, 31 Quay cranes, and a capacity of 5.5 million TEUs. The Port of Singapore has been the world's busiest port in terms of shipping tonnage since 1986.

Through their Web sites and software products, ITL companies do many of the things international trade specialists do (Figure 11.6). They let their customers know which international companies they can do business with and which companies can do business with them. They identify export and import restrictions between buyers and vendors. They provide the documents required to export and import products, and they determine the duties, taxes, and landed costs and other government charges associated with importing a product.

JP Morgan Chase Vastera, a global trade management company, enables customers through its web-based software products to calculate landed costs, screen for restricted parties, generate shipment documentation, and manage duties, and it also handles repairs and returns. It has an online library of trade regulations for different countries, and it's customers include Ford, Dell, and Toshiba. Other ITL firms include Trade Beam and Nistevo.

Two significant changes that prompted many U.S. companies to expand globally were the passage of NAFTA almost a decade ago and the admission of China into the World Trade Organization in 2001. NAFTA opened up business opportunities with Mexico, which in 2002 replaced Japan as the United States' second leading trading partner, with cross-border trade exceeding $240 billion. Approximately 700 of the Fortune 1000 companies have a portion of their operations, production components, or affiliates in Mexico. Besides cheap labor, Mexico is also close to the United States, and thus Mexican companies can meet the just-in time requirements of many U.S. companies. However, Mexico's economic gains also lead to more jobs and increased worker skills, and as a result, higher wages, which in turn has led U.S. and foreign companies away from Mexico to China with its even lower wage rates. The wage rate for unskilled labor in China is around $1.50 per hour compared to approximately $3.00 per hour in Mexico, $5 per hour in Singapore, and $25 per hour in Japan. As companies have moved their manufacturing into China because of lower labor costs, new low-cost Chinese suppliers have also emerged, and U.S., Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean suppliers have set up operations in China as well. This is basically the same pattern followed previously in Japan in the 1960s and 1970s and later in Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore before Mexico became a global hot spot. In 2003 China replaced Mexico as the number two exporter of goods to the United States.

Both Mexico and China have positive and negative aspects in terms of supply chain develop-ment for U.S. companies. You can ship from Mexico to the United States in about eight hours; however, it takes 21 to 23 days to ship from China. Many people speak English in Mexico, and many Americans speak Spanish; the same situation does not exist in China. Government regula-tions, especially in terms of business ownership, are sometimes restrictive in China, but in China a company can work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week compared to an average workweek in Mexico of approximately 44 hours. Trade regulations and tariffs are increasingly being lowered in Mexico and China.

Quality is a problem in both Mexico and China where it can vary dramatically between com panies. Chinese and Mexican suppliers generally lack quality-management systems and do not often use statistical process control or have ISO certification.

In recent years more and more companies in the United States and abroad are seeking to develop a global supply chain by sourcing in low-cost countries, and no country has received more attention as a supplier than China. Today, China has become one of the world's premier sources of supply. Not only are companies looking to China as a low-cost supplier of goods and services, but many suppliers are relocating to China. In 2006, IBM moved its global purchasing headquarters from Westchester County, NY to Shenzhen, China—the first time IBM has located the headquarters of one of its global corporate functions outside the United States. It relocated, in part, to help the company develop stronger relationships with its suppliers in China.

Companies are looking to China (as well as other emerging low-cost sources of supply such as Central/Eastern Europe, Mexico, India, and Pacific Rim countries) for several reasons. First there is an abundance of low-wage labor; China has a labor market of 750 million people, and the country's average hourly wage, although increasing, is still lower than most other emerging markets. The average worker earns about $1.50 up from 75 cents an hour a few years ago and migrant workers (who account for one-fifth of the labor market) typically earn less than $130 per month. Despite recent rapid growth, China's GDP per capita is still only about $3,200 compared to over $10,000 for Mexico. Almost half of China's population has a middle-school or greater education. Most companies that are global sourcing also want to position their source countries as future markets, and China is one of the world's fastest growing markets. China's exports increased by over 500% in the past decade. China's retail spending has increased by 12 to 16% annually in re-cent years. China has introduced a number of regulatory changes that has liberalized its market; and its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) came with a reduction in tariffs from almost 25% to a little over 9%.

Traditionally China has exported consumer goods, clothing and textiles; however, it is now increasingly exporting products with a higher technology content as its manufacturing sector matures. This is what most low-cost emerging countries do; ramp up with labor-intensive manufacturing and then migrate slowly toward more skilled, higher-value products and services. In particular, high-tech industries are looking to China as a low-cost supplier. Because high-tech companies operate on razor thin margins, with intense competition and very fast product lifecycles, they have no choice but to look to countries like China as a source of low cost supply. The Microsoft Xbox game system was first built in Mexico and Hungary, but production was shifted to China. Palm Pilots used to be built in the United States and Europe but are now mostly manufactured in China. Laptop computer manufacturing in Taiwan is moving to China.

United States companies generally follow one of several models in doing business in China. One option is to employ local third-party trading agents such as Chinese import and export companies (like Li & Fung) to help identify local suppliers, negotiate prices, and arrange logistics. Another alternative is a wholly owned foreign enterprise like Siemens that in return for a larger investment will typically provide a better understanding of suppliers, tighter control over quality, and more opportunities to form better long-term relationships with suppliers. Finally, companies can develop their own international procurement offices (like IBM did) that have specialized teams performing different sourcing functions like logistics. Of the three models, the establishment of an international procurement office has proven to be the most successful especially for large manufacturing firms.

Sourcing from China is not without challenges. Dramatic differences in organization, cultural relationships, and technology can result in significant problems to overcome. Most U.S. companies have spent years and resources building a network of reliable, high-quality suppliers, and disrupting that system in order to global outsource (often to remain competitive) can be a daunting task. Simply getting reliable information about Chinese suppliers in order to compare compa-nies is much more difficult than in the United States. Information technology is much less advanced and sophisticated in China than in the United States. Cultural relationships are more difficult to establish in China than in the United States. Guanxi (or personal relationships) will frequently trump commercial considerations in the negotiation process and in doing business. Worker turnover rates among low-skilled workers are extremely high, averaging 30–40% annu-ally, and the turnover rate among new university graduates is also extremely high compared to industrialized nations.

While China has become a burgeoning global supplier market, the country's underdevel-oped transportation infrastructure, fragmented distribution systems, lack of sophisticated technology, limited logistics skills, regulatory restrictions, and local protectionism hinder efficient logistics and make supply chain management a challenge. Companies entering the Chinese market often find they cannot manage transportation and distribution as they might in their home country. The government-controlled rail service is China's cheapest distribution mode; however, capacity shortages are routine. Roads are the preferred mode of distribution for pack-aged finished goods; however, demand exceeds capacities, and China's road transport industry is very fragmented. Airfreight is plagued by high prices, inadequate capacity, fragmented routes, and limited information exchange between airlines and freight forwarders. Ocean and inland water transport is the most developed distribution mode in China, and China's shipping companies rank among the world's largest. However, inland water distribution is underutilized because ports often cannot process and manage cargo efficiently, bureaucratic delays and theft are common, and many ports cannot accommodate larger vessels. Distribution is also hampered by poor warehousing, which is predominantly government controlled. Warehouse designs are inefficient with low ceilings and poor lighting, and goods are usually handled manually without warehouse automation.

Most supply chain functions in China are not logically linked to government departments. Logistics oversight is shared by different government entities such as various planning and trade commissions, and this shared responsibility creates problems with things like customs clearance including excessive paperwork, inefficient procedures, and short business hours. Complicated and excessive regulatory controls are also common. Foreign trade companies must sell goods through distributors and cannot sell directly to stores, and they are forbidden to own distribution channels. A foreign company can sell goods manufactured in China, but it cannot sell or distribute goods imported into the country, including those produced by a company's plants outside of China. Thus, foreign companies must rely on small local distribution companies to move goods. Regulations also have created a shortage of third-party logistics providers.

However, despite these problems China's distribution and logistics sector is growing and improving rapidly. Modernization of logistics and transportation was on one of the top three priorities in China's Tenth Five Year Plan that ended in 2005. Billions of dollars are being spent annually on new highways, airport construction and expansion, inland water transportation, and the construction of distribution and logistics centers. China's admission to the World Trade Orga-nization has forced the country to progressively remove regulations and restrictions that prevent foreign companies from participating in transportation and distribution functions, which has made it possible for foreign companies to establish subsidiaries and offices that manage a variety of supply chain functions. The demand for third-party logistics service providers has also expanded the outsourcing of logistics and transportation.

U.S. and European companies initially began expanding their supply chains and shifting operations into Asia, and specifically China, because of cheaper labor and raw materials. However, the trend toward partnering with Asian and Far Eastern suppliers, show signs of reversing itself as the gloss of global sourcing has begun to tarnish for some companies. As a result of increased capital, an improved infrastructure, and a higher standard of living, China is rapidly approaching a level of parity with other developed nations, mirroring a transition experienced in the past by other foreign countries like Japan, Taiwan, and India. Wage rates in Asia are steadily rising, thus negating one of the primary reasons for global sourcing. While Far Eastern and Asian countries are instituting new laws and port and trade regulations, countries in Latin America, South America, and Canada are investing more in education and infrastructure and developing larger and more modern port facilities, making it more appealing to source in this hemisphere. Volatile oil prices have made it more costly to ship items long distances and more difficult to predict costs; oil prices now account for nearly half of total freight costs. Shipping products over long distances while companies are demanding faster delivery times in a JIT-type competitive environment have contributed to an increase in containerization and faster ship speeds, which have increased fuel consumption. Increases in global transport costs have now effectively offset many of the trade liberalization agreements of the last 30 years.

Combined with these factors are the continuing unreliability of delivery times in longer global supply chains and quality failures, in China in particular. (See the "Along the Supply Chain" box on "Reverse Globalization at K'NEX). Recent surveys show that companies are increasingly con-cerned about the risk of poor product and supply chain quality (for example, the problem of lead paint in toys produced in China), and the infringement on intellectual property and security breaches in China. Long lead times resulting from distance and uncertainties in the shipping processes for global sourcing mean ordering far in advance, which can backfire if the product market changes or the economy sours. It is often difficult for U.S. companies to gain visibility into the financial health of foreign suppliers; during the recent global recession many overseas suppliers went bankrupt creating supply chain delays for U.S. buyers. All of these factors— increasing oil prices, higher foreign wage rates, increasing raw material costs, poor quality and long delivery times—have made what's referred to as near-shore sourcing in this hemisphere more attractive. Although wage rates are higher, many U.S. companies are moving operations and facilities back to the states, are partnering with U.S. suppliers or suppliers in this hemisphere, and some are insourcing. Near-shoring allows companies to reduce or avoid many of the risks associated with global sourcing, and shorter supply chains enable companies to gain more control and flexibility. Some companies, embracing customer concerns about service quality, are moving customer service and ordering processes from India back to the United States; even though it's more costly, maintaining customers and customer satisfaction is being recognized as the more important consideration.

Many U.S. companies are discovering attractive near shore suppliers in this hemisphere.

Brazil has 36 deep water ports making it an attractive "near shore supplier" for the United States Rio deJaneiro is the third busiest port in Brazil in terms of cargo volume and container movement; the port of Santos is the largest.

The events of 9/11 affected global supply chains as they have much of everything else in our lives. The two primary modes of transport in global supply chains are airfreight and ocean carriers, both of which enter the United States through portals from the outside world and thus are obvious security risks. Since 9/11, the U.S. government in concert with countries around the world has adopted security measures, which besides increasing security, has added time to supply chain schedules and in-creased supply chain costs. Air and ocean carriers must file an advance manifest with the U.S. government 24 hours before loading the containers on a U.S.-bound ship or airplane so the government can conduct "risk screening." This 24-hour rule requires extensive documentation at the airport or seaport of origin, which can extend supply chain time by three to four days. Even if shipments reach the U.S. port on time, stricter customs inspections can leave the shipment tied up for hours or days. For example, food imports can be diverted for inspections for possible bioterrorism alterations. For airfreight, a delay of three or four days would negate the benefit of shipping by air at all. As a re-sult of new security measures after 9/11, inventory levels increased almost 5% requiring more than $75 billion in extra working capital, as companies coped with delays with buffer inventory. The cost of insuring U.S. imports increased from $36 billion in 2001 to over $40 billion to 2002. The Brookings Institute has estimated that the cost of slowing the delivery of imported goods by one day because of additional security checks is approximately $7 billion per year. These costs do not even include the costs of new people, technologies, equipment, surveillance, communication, and security systems, and training necessary for screening at airports and seaports around the world.

In 2003 the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CPB) agency was established as part of the Department of Homeland Security to ensure that all imports and exports are legal and comply with U.S. laws and regulations. The CPB has implemented a comprehensive cargo security system designed to protect national security that includes the 24-hour manifest rule, a container security initiative, a customs-trade partnership against terrorism (C-PAT), non-intrusion inspection techniques, automated targeting systems, the national targeting center, and recently the secure freight initiative. The secure freight initiative, announced in 2008 to go into effect in January 2010, also known as the "10+2" initiative, is intended to reduce the rise of terrorism by using the latest tracking and tracing, and communication and reporting, technologies. It provides for a detailed security account of goods and materials shipped into the United States, called the Importer Security Filing (ISF), that distinguishes between potentially risky cargo and lower risk cargo, and more efficiently allo-cates agency resources to focus on true security threats. ISF 10+2 is mandatory for all importers; it includes "10" specific data elements related to container manufacturer, seller, buyer, content, importer, schedule, origin, and destination, that must be electronically filed 24 hours before loading any container on a ship bound for the United States. The "+2" are data files which the carrier must file within 48 hours of the departure time, and includes the location of all containers on the ship and information on the movement of containers and any status changes as they move through the supply chain. 10+2 was expected to increase annual supply chain shipping costs from $400 to $700 million as a result of government filing fees and the additional reporting information required.

continuous replenishment supplying orders in a short period of time according to a predetermined schedule.

core competencies the activities that a company does best.

cross-docking crossing of goods from one loading dock to another without being placed in storage.

e-marketplaces Web sites where companies and suppliers conduct business-to-business activities.

e-procurement business-to-business commerce in which pur-chases are made directly through a supplier's Web site.

intermodal transportation combines several modes of transportation.

landed cost total cost of producing, storing, and transporting a product to the site of consumption.

logistics the transportation and distribution of goods and services.

nation groups nations joined together into trading groups.

on-demand (direct-response) delivery requires the supplier to deliver goods when demanded by the customer.

order fulfillment the process of ensuring on-time delivery of a customer's order.

outsourcing purchasing goods and services that were originally produced in-house from an outside supplier.

postponement moving some final manufacturing steps like final assembly or product customization into the warehouse or distribution center.

procurement purchasing goods and services from suppliers.

reverse auction a company posts items it wants to purchase on an Internet e-marketplace for suppliers to bid on.

sourcing the selection of suppliers.

supply chain the facilities, functions, and activities involved in producing and delivering a product or service from suppliers (and their suppliers) to customers (and their customers).

supply chain management (SCM) managing the flow of information through the supply chain in order to attain the level of synchronization that will make it more responsive to customer needs while lowering costs.

tariffs (duties) taxes on imported goods.

trade specialists specialists who help manage transportation and distribution operations in foreign countries.

value added tax (VAT) an indirect tax on the increase in value of a good at any stage in the supply chain from raw material to final product.

vendor-managed inventory (VMI) a system in which manufacturers instead of distributors generate orders.

warehouse management system (WMS) an automated system that runs the day-to-day operations of a warehouse or distribution center and keeps track of inventory.

11-1. Describe in general terms, how you think the distribution system, for McDonald's works.

11-2. Discuss why single-sourcing is attractive to some companies.

11-3. Define the strategic goals of supply chain management, and indicate how procurement and transportation and distribution have an impact on these goals.

11-4. Identify five businesses in your community and determine what modes of transportation are used to supply them.

11-5. Pick a business you are familiar with and describe its primary transportation model and its transport routes.

11-6. Select a company and determine the type of suppliers it has, then indicate the criteria that you think the company might use to evaluate and select suppliers.

11-7. Select a company that has a global supply chain and describe it, including purchasing, production, distribution, and transportation.

11-8. Locate an e-marketplace on the Internet and describe it and the type of suppliers, and producers it connects.

11-9. Locate a transportation exchange on the Internet, describe the services it provides to its users, and indicate some of the customers that use it.

11-10. Explore the Web site of an enterprise resource planning provider and describe the transportation and distribution services it indicates it provides.

11-11. Locate an international logistics provider on the Internet; describe the services it provides and identify some of its customers.

11-12. Purchasing is a trade magazine that focuses on supply chain management and e-Procurement. Its articles include many examples of supply chain management at various companies. Research an article from Purchasing and write a brief paper on a company reporting on its procurement activities similar to the "Along the Supply Chain" boxes in this chapter.

11-13. Logistics management is a trade magazine that focuses on supply chain management, especially logistics. Its Web site is www.logisticsmgmt.com. The magazine includes numerous articles reporting on companies' experiences with supply chain management. Select an article and write a brief paper similar to the "Along the Supply Chain" boxes in this chapter about a specific company's distribution or logistics activities.

11-14. Describe the global supply and distribution channels of retail companies like L.L. Bean Sears, and J.C. Penney. What are some of their problems?

11-15. Walmart is one of the leaders in promoting the development and use of radio frequency identification (RFID) and electronic product codes. Explain how Walmart uses RFID in its procurement and distribution and why Walmart wants its suppliers to adopt RFID.

11-16. Describe the differences and/or similarities between VMI and postponement, and explain how the two might complement each other.

11-17. Explain how Walmart uses cross-docking to improve its supply chain efficiency.

11-18. Describe the supply chain for your university or college. Who are the suppliers, and distributors in this supply chain?

11-19. Identify three countries (other than Canada and Mexico) that you think would be possible near-shore suppliers for U.S. companies and discuss their advantages and disadvantages.

11-20. Discuss how sustainability can be achieved in transportation and distribution functions.

11-21. Using the Internet or your library find an article and write a report about how an actual company is achieving sustainability though improved processes in its transportation and distribution functions.

11-22. Discuss some of the disadvantages of U.S. companies using Chinese suppliers that might drive them to near-shore their supply chains.

11-23. Discuss why you think "reverse globalization" may, or may not, be a long-term trend

Somerset Furniture Company's Global Supply Chain–Continued

For the Somerset furniture Company described in Case Problem 10.1 in Chapter 10, determine the product lead time by developing a time line from the initiation of a purchase order to product delivery. Discuss the company's possible transportation modes and channels in China and to and within the United States, and the likelihood of potential problems. Identify and discuss how international trade specialist(s), trade logistics companies, and/or Internet exchanges might help Somerset reduce its product lead time and variability.