CHAPTER

Managing supply

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Case study

RS Components (Radio Spares) is a good example of an organization integrating its entire supply chain activities. RS provides a catalogue service to industrial and service firms. The catalogue covers all manner of items, ranging from transistors and resistors through to large-scale transformers and other heavy-duty equipment. This firm viewed itself as primarily a logistics and marketing operation, with purchasing performing the service role of providing the goods at the right time, right price and right quality. RS competes in a market with two other major firms, all using the same type of marketing channel (catalogue), and found that their sales were declining, and they were unable to differentiate themselves within the market place. They could not see how to overcome this problem, and could not understand how the purchasing function could possibly add any further value, other than logistical and inventory management. The key to their problem was that of strategic focus – i.e., where was value being added in the business? The company decided to form a ‘supply chain management’ team consisting of purchasing, marketing and logistics. After close analysis of their business they discovered that, whilst they could not offer suppliers joint risk sharing and value engineering work, they could offer market intelligence.

Essentially, RS were the link between the customers’ future requirements and their suppliers (manufacturers). If this communication flow could be optimized by clear and efficient communication, RS would be able to place new items in its catalogue almost 6 months before its competitors. This new approach had the effect of increasing customer loyalty and differentiating RS as a responsive supplier to market demands.

Why is purchasing and supply management such an important topic area? There are several reasons. First, the purchasing function has the responsibility for managing the timely delivery, quality and prices of the firm's inputs, including raw materials, services and sub-assemblies, into the organization. When we consider that many firms purchase around 80 per cent of their products and services, this is no small task. Secondly, any savings achieved by purchasing are reflected directly in the company's bottom line. In other words, as soon as a price saving is made this will have a direct impact on the firm's cost structure. In fact, it is often said that a 1 per cent saving in purchasing is equivalent to a 10 per cent increase in sales. Thirdly, purchasing and supply have links with all aspects of operations management, and so we need to understand their importance. Finally, the way a company controls its sourcing strategy will have a direct impact on how the firm does business. For example, the firm will sometimes ‘outsource’ elements of its business – including catering, travel, and aspects of information technology. The implementation and development of these approaches relies heavily on purchasing's expertise. It is important to understand how purchasing and supply are linked with operations management in the provision of goods and services to the end customer.

Aims and objectives

Aims and objectives

This chapter will discuss supply management and how it affects business.

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

![]() Explain the development of purchasing into strategic supply

Explain the development of purchasing into strategic supply

![]() Outline the various sourcing strategies available to the firm

Outline the various sourcing strategies available to the firm

![]() Explain when, why and where each strategy should be used.

Explain when, why and where each strategy should be used.

UNDERSTANDING SUPPLY

UNDERSTANDING SUPPLY

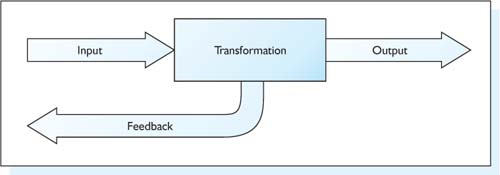

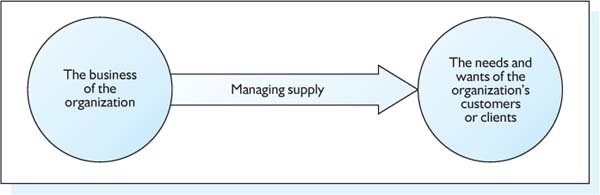

The easiest way to think about how purchasing affects the firm is by using a simple input–transformation–output model or systems model such as that we first saw in Figure 1.3. We have modified this in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Input–transformation–output model.

The first key point is to understand the distinction between purchasing and supply. Purchasing is defined as managing the inputs into the organization's transformation (production) process. Supply, on the other hand, is the process of planning the most efficient and effective ways of structuring the supply process itself. This not only includes inputs but also, to a large extent, the transformation process itself.

Purchasing's role has traditionally been seen as a service provider to the other functions within the business. The primary task of purchasing was to buy the goods and services from approved sources of supply, making sure that they conformed to the required levels of quality and performance, delivery schedules and the most competitive price.

This view of purchasing as a service department, performing predominantly a clerical role, is changing rapidly. Purchasing (or supply as it is now more commonly known) is viewed as an important and strategic process. In order to reflect this important role, many large organizations have divided the purchasing and supply elements of the business into two distinct parts:

1 Purchasing, which deals with the day-to-day buying activities of the firm; and

2 Supply, which is concerned with the strategic planning, goal setting and strategy development in optimizing how the firm better manages its supply process.

The role of strategic supply is to assess the options for outsourcing elements of the business. It examines how the supply structure should be organized and deals with strategic questions, including whether the business should buy from many suppliers, or have fewer suppliers who make up larger elements of the business. Once these questions have been answered, specific strategies then need to be put in place. One such strategy is known as supply tiers, and the trend for ‘mega’ or ‘first-tier suppliers’ is currently being pursued by a number of firms. For example, in both aerospace and automotive manufacturing there are now many ‘first-tier’ suppliers. ‘Mega’ suppliers are responsible for providing an entire subsystem (for example the entire wing or gearbox), as opposed to the traditional method, where many suppliers would provide their individual element and the manufacturer would assemble the parts. The idea is that a first-tier supplier will now do the majority of the coordination and assembly work for the customer, and the prime manufacturer then simply slots the elements together to form the finished product. In doing so they have re-evaluated what is core to their business and then used the supply strategy to allow them to focus upon this. This change in the focus of a company's business allows it to become more flexible and to concentrate on what it does best. It is through taking a strategic supply focus that these changes are achieved.

Motivations for the development of purchasing

Motivations for the development of purchasing

towards supply management.

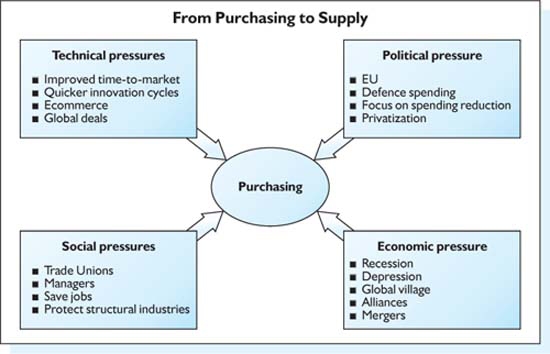

There are many reasons for the transition of purchasing form a clerical to a more strategic focus. Purchasing has had a range of pressures upon it that have forced it to change. A simple PEST (political, economic, social and technological) model can be used to illustrate this point. Figure 5.2 illustrates the PEST analysis, showing the forces of change on purchasing that have acted as a catalyst to move it from a clerical function to a strategic process.

Figure 5.2 Pressures on purchasing to change.

Political factors

Political factors

Political pressures have caused changes in both the focus of supply – for example, the change of emphasis from price to cost focus – and the change in the structure of industries. This has become evident in government policy on privatization in many public services. The introduction of the Public Private Finance (PPF) initiative has had a major impact on how public sector firms now fund major projects. Instead of the government being the sole source of funds, public bodies now form relationships with the private sector to fund the projects jointly (with government guarantees). These major policy changes have meant that within certain industrial economic sectors the focus of the organization as a whole has had to change. This has developed from defining the ‘best’ specification possible towards finding the lowest cost solution. For example, defence spending reductions, combined with a policy change allowing sourcing of components to come from non-domestic manufacturers, caused a massive shockwave throughout that industry. The aerospace industry had to change from its traditional ‘cost plus’ focus and concentrate on ‘value-for-money’, thus moving towards a cost-focused approach. Cost and price are not used interchangeably here. Price refers to the process of driving down the quoted price of the goods, and this will often have the net effect of reducing the supplier's margin. Cost is a more sophisticated approach, which focuses on understanding the entire cost of the product (including process) and then jointly finding ways to reduce this.

Further policy changes (such as privatization) moved public sector services into the private sector, where the pressures of competition and cost competitiveness are much higher.

Economic factors

Economic factors

Economic pressures also forced organizations to examine the way that they managed supply. Recessions and depressions, together with competition on a global as opposed to a domestic level, meant that increased costs could not be passed onto the final consumer. Instead they had to be either absorbed, resulting in lower profits, or passed back, which often meant that suppliers would go out of business; alternatively, these costs had to be eliminated. This era of the late 1980s and early 1990s saw the development of concepts such as lean manufacturing and lean supply management. The focus with all of these approaches was primarily on improving efficiency and reducing waste both within the organization and within the firm's supply chain, thus resulting in overall cost reductions to the firm.

Social/image changes

Social/image changes

Social pressures have also forced purchasing to change. If purchasing wanted to enhance its image, it would need to utilize professional and well-qualified personnel. In order to attract these types of people into the area it would need to present a professional profile similar to that of finance or marketing. Purchasing's main problem was that it was not seen as ‘sexy’.

Wickens (1987, p. 162) commented how image was a problem in the 1980s for production and supply:

The best graduates want to go into merchant banking, the professions, the Civil Service, the finance sector. If they think of industry or commerce it is in the areas of marketing, sales, finance or personnel that attract.

This view is now beginning to change as purchasing achieves higher strategic status within the organization. In addition, purchasing now has a professionally chartered institute, along with other major functions such as marketing, production and finance. All of these elements help in raising the profile of purchasing. Further social pressure on the firm by other stakeholders to save money, and therefore jobs, was exerted by trade union groups and various pressure groups both within and external to the firms.

Technology factors

Technology factors

The development of new and innovative technologies has meant that purchasing can communicate and involve a much wider range of the organization in the supply process. For example, it is now possible, via the Internet, to allow anyone (subject to their being authorized budget holders) to purchase against an E-catalogue. Purchase cards (credit cards for managers) are also revolutionizing the way that we do business. In addition to technologies that facilitate the purchasing process, firms are also requiring improved times-to-market of their own products. This can only be achieved if the supply structure is able to deliver quality suppliers that can work with the buyer.

The need to be increasingly competitive, flexible and efficient has been exacerbated by the global village phenomenon, with domestic firms having to benchmark with the best in the world.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, many firms adopted in-vogue production techniques and concepts such as just-in-time (JIT) and total quality management (TQM), which will be discussed in later chapters. During the early to mid-1980s the concept of the value chain was first proposed, which, being a systems model, involved the purchasing (input) function. Firms began to realize that the concepts of JIT, TQM and world class manufacturing (WCM) would only work if the supply process were also closely managed. This led to the development of a new buzzword, ‘partnership sourcing’. The CBI and DTI created an entire organization to promote partnership sourcing throughout UK industry.

THE EVOLUTION FROM PURCHASING TO

THE EVOLUTION FROM PURCHASING TO

SUPPLY MANAGEMENT

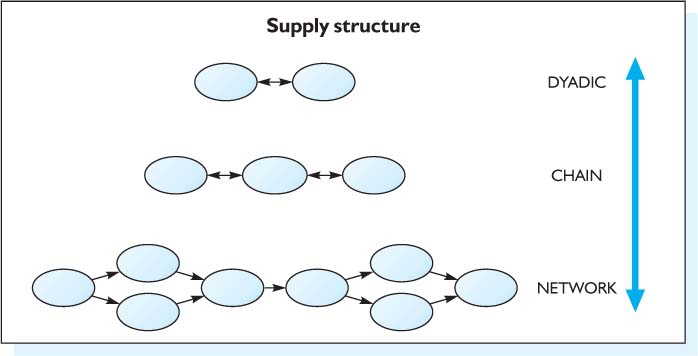

How we think about supply management has changed, and this is illustrated in Figure 5.3. Initially, purchasing focused on the dyadic linkage between a buyer and supplier. In the late 1980s, supply chain management focused on supply as a chain or pipeline, taking account of the buyer, supplier and final customer relationships. Finally, strategic supply views supply as a network of relationships across an entire industry sector, where buyer and supplier roles can be interchanged several times during the network.

Figure 5.3 The supply structure (source: Harland et al., 1999).

Managing supply is difficult, because it relies heavily on cross-functional cooperation. Often buyers do not consider the entire supply chain and its interfaces – supplier/buyer, buyer/customer, and internal buyer/buyer. Organizations need to form linkages throughout the entire supply network, as shown in the following example of an integrated supply network.

Supply: a strategic process?

Supply: a strategic process?

The creation of strategic purchasing departments has transformed purchasing from a clerical function to a strategic business process. However, there is a difference between implementing strategies and being strategic. As Ellram and Carr (1994) point out:

It is critical to understand that there is a difference between purchasing strategy and purchasing performing as a strategic function. When purchasing is viewed as a strategic function, it is included as a key decision maker and participant in the firm's strategic planning process.

For example, a major aerospace company was developing a procurement strategy, and needed to confirm that it was aligned with the supply and corporate strategies. When the Purchasing Director was asked if he knew the firm's corporate strategy, he replied that he didn't, but would find out. Later, he reported: ‘I went to the Corporate Planning Director and asked him what was the strategy so that I could align my work to the needs of the organization. He replied that it was a secret, there was no way that this information could be given to me!’ Clearly the firm either had a very strange view of strategy, or it had no strategy at all. Neither situation would be particularly helpful in developing strategic alignment.

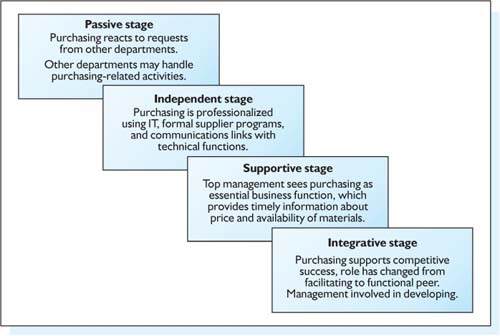

Figure 5.4 Strategic positioning tool (adapted from Reck and Long, 1988).

What, then, is the difference between implementing a strategy and acting strategically? Several tools and frameworks measure how strategic a purchasing department is. One is Reck and Long's (1988) four-phase positioning tool, shown in Figure 5.4. This positions purchasing capability from ‘passive’ through to ‘integrative’ within the overall business. This tool can be used as a detailed benchmarking mechanism for firms to position themselves in order to make changes.

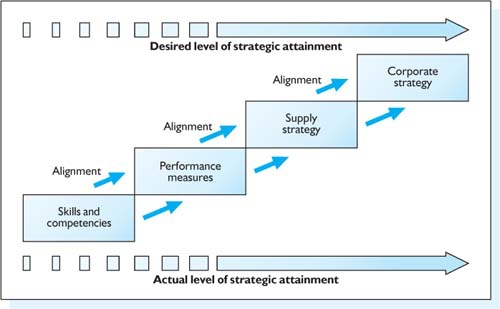

Another way to examine the strategic contribution of supply is in the strategic alignment model in Figure 5.5, which shows how supply strategy should be aligned with corporate strategy. It also shows that both of these must be supported (and aligned with) performance measurement systems and the skills and competencies of the people in purchasing.

Figure 5.5 The strategic alignment model.

Many companies focus on aligning supply and corporate strategy, and ignore performance measures and skills and competencies. In most ‘strategic’ purchasing departments performance is still measured by ‘lead time, quality and rejects’, which are tactical measures. Tactical measures encourage tactical behaviour. Strategic purchasing relies on strategic measurements. For example, cross-functional teams should be measured on team output, not on individual performance.

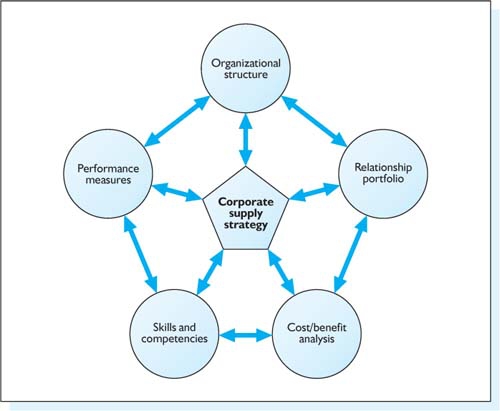

The strategic supply wheel in Figure 5.6 illustrates an integrated approach to supply strategy. Strategic supply must balance all of the elements in the wheel, rather than concentrating on a single element. A firm cannot focus only on relationship management without also considering skills and competencies, performance measures, costs and benefits and so on. The supply wheel and strategic sourcing strategies will be explained in detail later in this book.

The strategic supply wheel is used to show that in order for supply to be viewed as strategic, it must balance out all of the elements of the model. It is insufficient to concentrate on just one element within the model; in addition it is about finding appropriate strategies within the model. It is not sufficient for a firm to focus its efforts on relationship management without also considering all of the other key factors now discussed.

Figure 5.6 The strategic supply wheel (from Cousins, 2000).

Key issues in the supply wheel

Key issues in the supply wheel

Performance measures: One of the central issues within any firm is the concept of performance measures. These can be thought of as both internal and external measures. Within supply, external measures are often referred to as ‘vendor assessment’ schemes. These are mechanisms that firms use to assess the performance of their suppliers. For example, they are likely to measure a range of capabilities, including delivery performance, price competitiveness, and quality and defect rates. There will also be internal measures focused on the buyers; these will generally focus on price, delivery and quality. The key here is to make sure that the internal and external measures align. In addition, measures should be appropriate, so if we are buying nuts, bolts and rivets (low value, high volume items) it is likely that we are going to measure how quickly these things are being bought; these are known as efficiency measures. On the other hand, if we are buying more complex and expensive items – for example, a computer system (low volume, high value) – it is less likely that we are interested in how quickly the item is bought; rather, we shall measure in terms of how the product has met our design specifications. These types of measures are known as effectiveness measures, which focus on how well we are achieving against our strategy as opposed to how quickly are we doing things.

It is vitally important that these measures are aligned with the strategy that the firm wants to pursue. If the firm is looking to build long-term relationships, then it will need to develop more effectiveness-focused relationships. If it is into short-term cost savings, then it will need to focus more on efficiency measures. It is, however, likely that the firm will be need to pursue both strategies, depending on what it is buying. We will see later on in this chapter how this can be achieved through using a product position matrix.

Relationship portfolio. This refers to the range of relationships that a firm can have with its suppliers. These can be very adversarial and traditional in nature. In this scenario, the relationship is focused on driving hard deals based (usually) around price. Alternatively, at the other end of the spectrum, the relationships can be much more collaboratively focused. This is where the firms will work with each other to try and find ways of reducing costs (the use of cost transparency, i.e. sharing joint cost of information). They may also share technologies and innovation ideas, jointly developing products between them. The process is sometimes referred to as ‘partnership sourcing’. Again it is vital that these strategies match with what the firm wants to achieve and that the measures, which motivate people, are focused on delivering the correct relationship strategy. Traditional relationships will generally focus on efficiency-based measures, whereas the more complex collaborative relationships will require much more effectiveness-based measures.

Cost/benefit. This refers to the amount of money that will be saved by pursuing a given strategy, and the cost to the firm of following that route. If the cost is more than the given benefit, then it is unlikely that the firm will follow the strategy. If the reverse is true, it seems like a good strategy to follow. Therefore, whatever strategy is considered the firm should be clear about possible outcomes. For example, if a firm wishes to pursue the collaborative relationship strategy, then questions must be asked about the costs involved in setting up the teams, the risk of focusing on only one supplier, exposing cost information, and so on. We must then evaluate the potential benefits of pursuing such a strategy. This may include reduced overall costs for both firms, improving time-to-market, developing new technologies and so on.

Organizational structure. This refers to the type of control mechanism the firm is using. Whilst there is a range of different structures that could be discussed, they can basically be classed into three distinct groups; centralized, decentralized and hybrid. Table 5.1 summarizes the main characteristics of each.

The way a function is structured will affect the way it interacts with other functions within the firm (dynamics). There has been a trend for firms to centralize purchasing, thereby realizing economies of scale from bulk purchasing. This has the disadvantage of potentially not satisfying local customer needs and wants. The reverse trend then followed, which was to decentralize, thus securing customer satisfaction. This in turn lost some of the economies of scale and management.

Table 5.1 Characteristics of organization structure

Organization structure |

Characteristics |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Centralized |

This is where purchasing activity is centralized in one major location. Head office is responsible for all of the purchasing for the firm |

The main advantages are: economies of scale, centralized expertise, easier management of the process, experts are easy to find. Global sourcing as opposed to local sourcing. Therefore, find the best deal |

The main disadvantages are: does not tend to be customer focused, can become bureaucratic, buyers have to constantly travel to meet supplier, customers etc. |

Decentralized |

Purchasing is conducted at a divisional level. Each division will have a budget and will focus on its own individual requirements |

Tends to be very customer-focused. Very responsive to customer needs. Source locally and manage quality levels locally |

Tends to be more expensive, miss out on global deals. Less strategic and more transaction focused. Lacks economies of scale |

Hybrid |

The hybrid is a middle ground model, which is both centralized and decentralized. This will consist of a centralized purchasing area that focuses on supply chain effectiveness. They will negotiate corporate deals and examine ways of optimizing supply chain efficiency. Day-to-day procurement is handled by the divisions |

This model allows for the advantages of both the centralized and decentralized model to be realized |

The main disadvantage of this model is that it is very difficult to control. When it works well the returns are very high, if it works badly the reverse is true! |

The current trend would appear to be a hybrid structure. This structure is both centralized and decentralized at the same time. Whilst this is naturally more complex to manage, if operated properly the benefits of both structures can be realized.

Skills and competencies. To pursue any of the chosen strategies at the centre of the strategic supply wheel model, the firm will need to have the appropriate skills and competencies within its employees. If the firm decides that it wants to develop long-term relationships with its suppliers, then it will need to make sure that the various supply personnel are trained in the correct manner. In essence, they will need to think strategically.

As with all of the previous circles in the strategic supply wheel, the appropriate skills and competencies must match the strategic direction, be supported by appropriate measures, operate within an appropriate organizational structure and aim to achieve a range of benefits at minimal cost. The strategic wheel is a useful diagnostic tool for considering the strategic nature and intent of the firm.

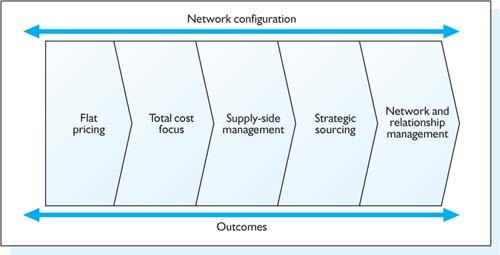

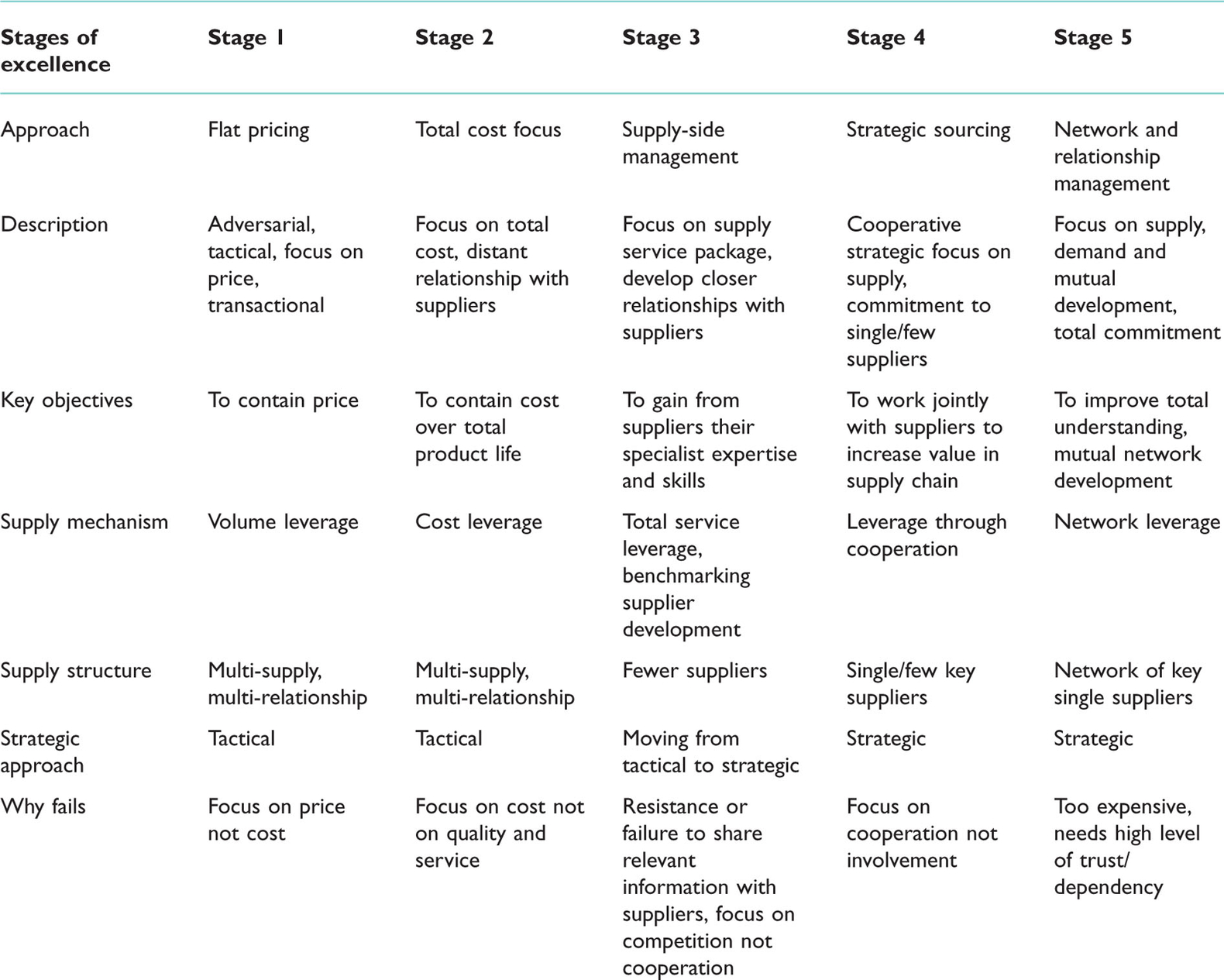

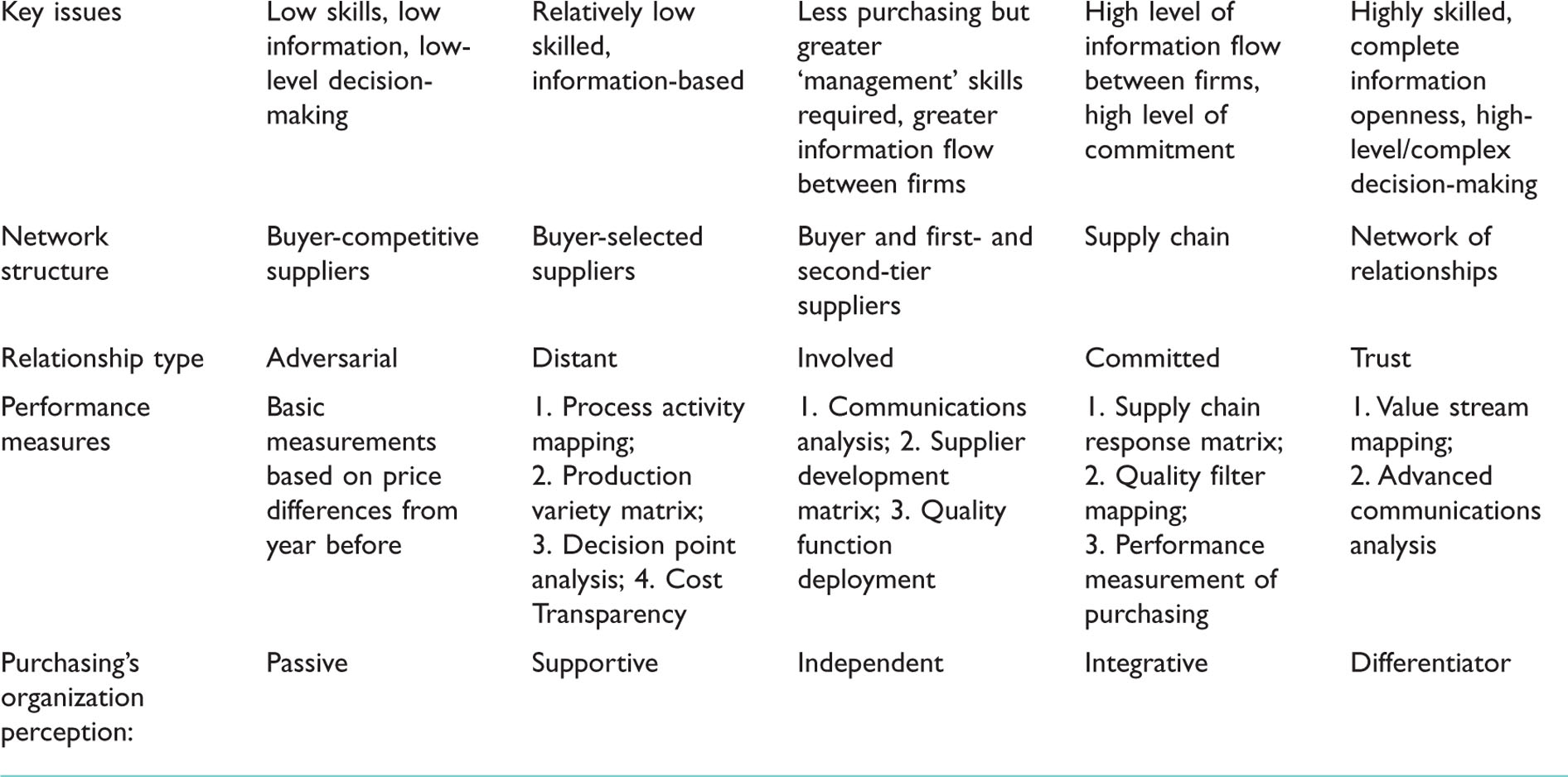

Another model that provides insight is the Strategic Transition model. This model (Figure 5.7) shows the various supply strategies available to a firm, which are are summarized in five main forms: flat pricing, total cost focus, supply-side management, strategic sourcing, and network and relationship management.

The model shows the movement from a purchasing focus on ‘flat pricing’ at one extreme towards ‘network and relationship management’ at the other end of the spectrum. Each of these five phases has a given output, and a set of characteristics that defines it. This model identifies nine key elements involved in purchasing strategy: key objectives, supply mechanism, supply structure, strategic approach, why fails, key issues, network structure, performance measurement and purchasing's perception within the organization (see Table 5.2).

Figure 5.7 The transition model.

The factors are then mapped against the overall ‘Transition model’, which enables a matrix to be produced that allows firms to see their relative positioning. The matrix is shown in Table 5.3.

Table 5.2 Purchasing assessment factors

Factor |

Definition |

Key objectives |

Refers to the main goal of the purchasing functions i.e. price reduction, cost improvement, relationship development etc. |

Supply mechanism |

Shows how the purchasing function uses its position within the supply chain to achieve the key objectives, such as price leverage, cost transparency, benchmarking etc. |

Supply structure |

Refers to the structure of the supply market – for example, is it multi-sourced, single sourced, dominant supplier, buyers’ market etc. |

Strategic approach |

This is the focus of the purchasing organization; is it predominantly short term, fire-fighting and tactical, or longer term, proactive and strategic? |

Why fails |

This category was placed in the model as respondents felt that in order to move on to the next phase they needed to understand why their current approach was not sustainable. Reasons for failure could be the focus of the approach was more on price than on cost, less on quality than on service and so on |

Key issues |

Refers to common problem areas realized with these strategies, such as skill base requirements, resource development, technology infrastructure etc. |

Network structure |

This category was used to show the type of interfaces that are most prevalent, i.e. buyer–supplier, one-way, or two-way, customer–supplier–customer, or indeed, network structure |

Relationship type |

Refers to the dominant relationships within the model, such as traditional/adversarial through to long term, close collaborative |

Performance measurement |

This is a key characteristic; it is essential to have the correct measurement systems in place. Measurement systems refer to internal as well as external measures |

Purchasing's organization perception |

The final characteristic refers to how the rest of the firm sees purchasing. This is an extremely important factor, and one that will directly influence the way in which purchasing can and does interact with the rest of the firm. The higher the perception within the organization, the greater the resource allocation and ability to effect change within the firm |

Table 5.3 Transition positioning matrix

Application of the Transition model

Application of the Transition model

This model has three clear implementation stages: assessment, strategy development and benchmarking. These are summarized in Table 5.4.

This model allows for a more comprehensive assessment of purchasing's strategic ability. This type of benchmarking creates a tool for managers to improve the effectiveness of purchasing activities. These types of approaches lead to the improvement of the overall focus of the purchasing department, and also can improve the organization's perception of the function. Once activities have been positioned and assessed against the ‘Transition model’, managers are then able to allocate time and resources most effectively to the activities under their control.

Table 5.4 Stages of implementation of the Transition model

Stage |

Purpose |

Description |

1 |

Assessment |

The purchasing organization should benchmark where it currently sees itself against the characteristics and criteria listed within the model |

2 |

Strategy development |

Purchasing should consider where it wants to be and examine the gaps in its approach vis-à-vis what the model is telling it, and should then develop a strategy to take the function forward |

3 |

Benchmarking |

The final stage is to use the model to review current progress and see how the function is developing |

The use of the ‘Transition model’ allows purchasing managers to understand clearly how the management of the purchasing activities needs to be changed, how resources can be distributed most effectively and can adjust the profile of the department within the organization.

SOURCING STRATEGIES

SOURCING STRATEGIES

There are a variety of ways that a firm can organize the supply process into the organization, and these are known as sourcing strategies. The rationale for these different approaches will come from a variety of factors, including the evaluation of how important the goods or services of strategic supply are to the firm and determining the competitive nature of the market place. In addition, the firm must also consider the level of technical complexity within the product.

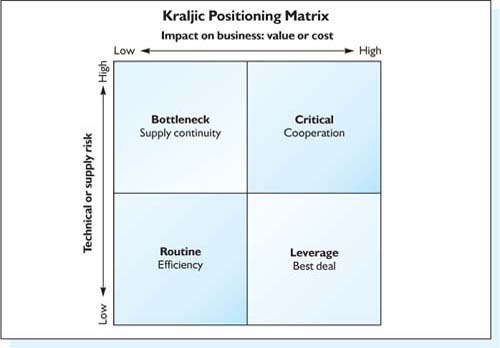

Kraljic (1983) developed a positioning matrix to help consider these and other factors to help buyers and suppliers in their sourcing and competitive positioning strategies. He identified four key purchasing approaches or strategies: routine, bottlenecks, leverage and critical. These are represented on the following matrix. These strategies are positioned against the level of supply exposure and/or technical risk compared with the strategic nature of the product or service – i.e. the level of value or cost exposure to the buying firm. Figure 5.8 illustrates the basic positioning matrix in which buyers can position the types of products and services that they purchase. These groups are termed ‘sourcing groups, which refers to a range of products or services that might be purchased. For example, nuts, bolts and rivets are often referred to as a Maxmin sourcing group. This is because the buyer will order to maximum and minimum stock levels.

This matrix is very simple but also very powerful, and has proved to be invaluable to firms in enabling them to focus on their procurement approaches.

The technical or supply risk can be derived from a few key factors. First, if there are only a few suppliers in the market place then the supply exposure is likely to be very high (the supplier will have all of the power in the market place). Alternatively, the supplier may possess superior technological skills, competencies and/or capabilities. This will give them a competitive advantage in the market place and therefore create higher degrees of dependency. With respect to the matrix, the buyer must weigh up the relative scale of high versus low (which is always an inherent weakness of this sort of model) and establish where the supplier best fits. The horizontal axis refers to the level of impact that the supplier's product or service has upon the customer's (buyer's) ability to deliver the final product. Value or cost is used because the item could be of relatively low cost, but of high ‘strategic’ value to the buyer's product. For example, in the aerospace industry a helicopter's gearbox is held in place primarily by several large bolts. Whilst these bolts are relatively inexpensive compared to other elements of the aircraft, i.e. avionic systems, they are of high strategic importance and value, because without them the gearbox would fall out!

Figure 5.8 Strategic positioning matrix.

The strategic positioning matrix suggests several strategies that the buyer might choose to follow. If the product/service is of low value/cost and low technical/supply risk, it is seen as a low level part or commodity type product. Examples include nuts, bolts and rivets in manufacturing. Types of stationary or low level temporary labour hire would also fall into this category, and should be sourced from the most efficient suppliers. The objective would be to get the most competitive price for the product, whilst maintaining delivery and quality standards. As switching costs are low and the market is highly competitive, buyers would negotiate over price. This often involves a Dutch auction approach, where the buyer will bid the price of the parts down sequentially, telling each supplier what the previous supplier has bid. This is a short-term strategy used to get low prices for the product.

If, on the other hand, there are few suppliers in the market place and/or the part or service has high degree of technological competences, then the sourcing strategy will be different. These are recognized as ‘bottleneck’ items. Here the strategy is to maintain supply continuity, and this may be achieved through the establishment of long-term contracts. The focus of the buyer will tend to be more on cost than simply on price, and the buyer will also be interested in maintaining the continuity of supply. Liquidated damages clauses are often put in place in these types of contracts in order to maintain continuity of supply.

Moving to the high value/cost items, the model suggests using different strategies depending on technical and/or supply exposure to the market place. For example, where the buyer perceives the exposure to the market place to be low yet the cost or value of the item is high – in automotive, for example, this may be a product such as car seats – the strategy would be to negotiate the ‘best’ deal. This can be obtained through the use of ‘leverage’ strategies (Porter, 1980). Leveraging involves pulling together a range of similar products (or sometimes the same product bought at different locations throughout the firm) and making a larger contract as a result. The aim of this approach is to increase bargaining power, thus establishing a much stronger negotiating position. For example, the buyer of seats, instead of sourcing Model A with Supplier 1, Model B with Supplier 2 and so on, would source both models from the same supplier. This will give the buyer the advantage of economies of scale, thus allowing a stronger negotiation position from which to leverage. Firms who are pursuing a strategy of cost reduction consistently follow this strategy. This approach to purchasing can and often does change the nature of the supply market exposure.

The supply market exposure will tend to increase as the buyer moves from several suppliers to one major source, and this will increase the dependency relationship and tend to move the supplier into the top right-hand box of Figure 5.8. This process often occurs without the buying company realizing the effect of the strategy, and there are many examples of this in recent years, with companies pursuing cost minimization programmes leading to large-scale supply base consolidation (Cousins, 1999). This leads to the final quadrant, where there is high exposure to the supplier and high impact upon the business (value and/or cost). These products or services are often seen as critical or strategic to the business. These would tend to be high value items, often with mega suppliers created through leveraging strategies. Examples of these types of products would be modular assembly supplies (from first-tier suppliers and key technology suppliers). In services there are many examples of major outsource providers, such as key suppliers of information technology – companies such as EDS and CSC Index take over the operations of the firm's entire IT network. These relationships tend to be single or sole sourced. This is mainly due to the large amount of investment required; switching costs are generally prohibitively high, with mutual dependencies. These relationships need to be managed very carefully, and they are seen as very long-term with the focus on partnership as opposed to buyer/supplier.

Figure 5.9 Leveraging strategies.

Supply structure and design

Supply structure and design

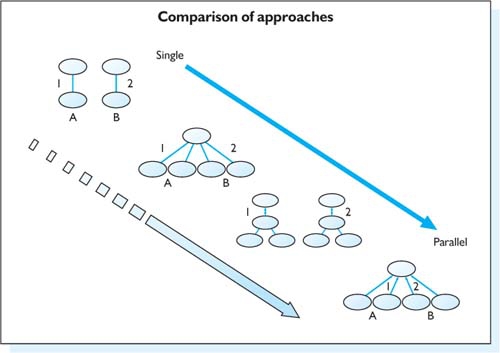

For each of the quadrants on the model, the sourcing strategy will need a requisite sourcing or supply structure. It is important to choose the correct design of structure to suit the strategy and type of procurement. There are four primary sourcing structures that can be used (plus some amount of variation on these): single, multiple, delegated and parallel (see Figure 5.10).

Figure 5.10 The four main sourcing structures

The above figure illustrates the complexity of the various sourcing approaches, ranging from the simplest structure, single or sole sourced, to the more complex structures of delegated and parallel sourced. It is the role of the buyer to decide when and where to apply each of these structures, and this will be dependent upon the needs and wants of the firm, the types of relationship desired and the levels of dependency that both buyer and supplier are prepared to take. It is interesting to note that the most dependent relationship is found in the simplest structure – i.e. the sole or single sourced arrangement.

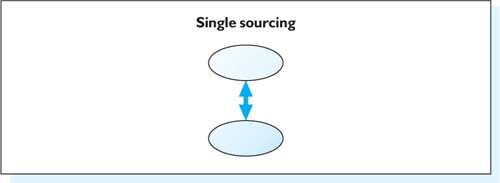

Single sourcing

Single sourcing

This structure is where the buyer has only one source of supply (Figure 5.11). This could come from a decision to use one source because of the high cost of the item or because of the strategic importance to the end product.

The most common reason for sole sourcing is that there is only one source of supply. Using the strategic positioning matrix (Figure 5.8), this type of approach would put the supplier in either the top right (critical) or top left (bottleneck) box. The advantages of managing this type of relationship are that there is only one supplier; it is therefore easier to exchange ideas and cost structures and to look for ways of mutual improvement of the product and processes. It is also easier to instigate a long-term arrangement. The disadvantage is that there is only one source of supply, and this could put the buyer in a position of weakness or over-reliance if not managed properly. In addition, if the supply source were to cease business for whatever reason, the customer would be highly exposed in the market place.

Figure 5.11 Single sourcing strategy.

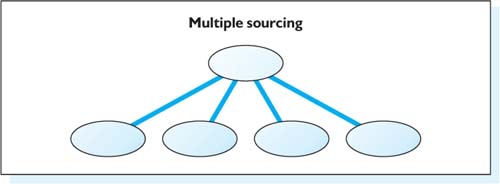

Multiple sourcing.

Multiple sourcing.

Multiple sourcing is defined as having several supply sources to supply the product, and is illustrated in Figure 5.12. The structure is often used to maintain competition in a given market place.

Figure 5.12 Multiple sourcing strategy.

The buyer will have a range of suppliers to choose from, and will carefully balance capacity constraints with individual supplier performance when placing orders. The old adage, ‘don't put all your eggs in one basket’, is often used to describe this supply structure. Buyers will also frequently enter into the ‘Dutch auction’ mentality and bid suppliers off against each other to achieve the best price. This is often seen as an adversarial approach and is most common in market places where this a high degree of competition, low switching costs and low levels of technological competence. This structure would tend to appear more in the bottom left (routine) box of the strategic positioning matrix, indicating low-level type purchases. Buyers using this model will tend to concentrate on a price as opposed to cost focus. This approach will enable some continuity of supply (certainly in the short term), and it will allow the buyer to achieve price reductions, although often the market tends to suffer from collusion and prices tend to rise. There is little chance of the buyer being able to operate sophisticated strategies such as cost transparency and partnership sourcing approaches. This model has traditionally been the mainstay of procurement strategy, but it is currently being replaced by more sophisticated and value adding approaches such as delegated and parallel sourcing.

Delegated sourcing strategy

Delegated sourcing strategy

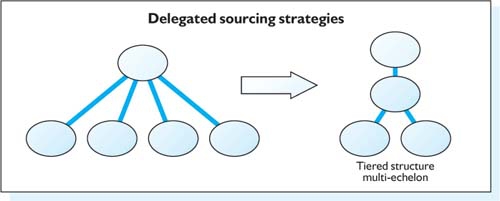

This approach became very popular in the mid 1990s across a wide range of industries, and is illustrated in Figure 5.13. It was first pioneered in the aerospace and automotive industries, as a more efficient way of managing supply (Cousins, 1999).

This structure involves making one supplier responsible for the delivery of an entire sub-assembly as opposed to an individual part, and the customer delegates authority to a key supplier. This supplier is known as a first-tier supplier. The principle is that the customer only manages one supplier, and that the supplier manages the other suppliers that provide parts to complete the product – as is shown in the following example.

A major car manufacturer was investigating how it could reduce the amount of suppliers to its business, but still maintain quality, cost and delivery requirements. They decided to implement a tiered structure approach to supply management. This would mean that they would be able to work closely with one key or first-tier supplier, and could exchange learning and also develop a clear integrated cost structure. The buyer firm would also not have to assemble the part themselves, because it would arrive complete and thus be inserted directly onto the vehicle.

The buyer decided to choose a major product area, which was the wheel assembly. After looking closely at the suppliers it was decided that the bearing manufacturer should be the prime or first-tier supplier. It was this manufacturer's responsibility to provide the buyer with a completed wheel assembly. This resulted in moving from a multiple sourced to a delegated sourcing strategy.

Figure 5.13 Delegated sourcing.

The move significantly reduced the amount of suppliers to the customer (95 per cent reduction). It also enabled the manufacturer to focus its resources on the first-tier supplier.

Delegated sourcing has a number of advantages for both the customer and the supplier. Focusing on one supplier gives the buyer the opportunity to work closely with this supply source instead of many, thus reducing day-to-day transaction costs. The increased dependency on one supplier results in the buyer and supplier exchanging more detailed information, particularly around cost issues (implementing cost transparency techniques is commonplace, otherwise known as ‘open book’). The buyer will pass on capabilities and technologies to the supplier to enable production the required sub-assembly. The supplier in turn becomes a major player for the buyer. This also increases the dependency from the supplier's perspective, giving the supplier more authority and control over the delivery and production of the sub-assembly. The process of delegated sourcing tends to create ‘mega’ suppliers. These suppliers, if not managed properly, can became very powerful and then exert their power over the buyer, usually in the form of price increases. It is vitally important for the buyer to make sure that when these arrangements are put in place, the dependencies are well understood and managed. This strategy would often be found initially in the ‘leverage’ section of the matrix, and in the medium term, due to the high dependency and high switching costs, it would move into the ‘critical’ area (top right).

Parallel sourcing

Parallel sourcing

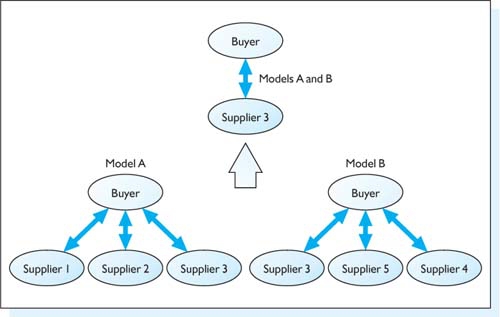

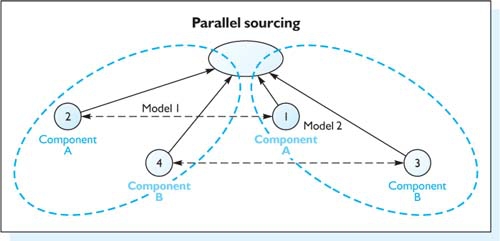

The concept of parallel sourcing (Figure 5.14) is quite difficult to describe. Richardson (1994) developed the concept in the early 1990s, and claims that the supply structure will give the buyer the advantages of both multiple and single sourcing without the disadvantages of each.

This model looks very complicated, although the principle is quite simple. It involves splitting the supply over a variety of models; thus Suppliers 1 and 2 supply the same component, but across different model groups – i.e. Supplier 2 supplies to model one, and Supplier 1 to model two. This allows the buyer to maintain competition across model groups; it also facilitates benchmarking of price and performance. This is a complex structure to manage, but does have the advantage of maintaining competition. This structure would generally be found in the ‘leverage’ box of the strategic positioning matrix.

Figure 5.14 Parallel sourcing.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

The area of purchasing and supply management is of growing importance to organizations. With the pressures of increased competition, improved time-to-market and cost reduction, organizations have to respond by re-engineering their supply structures to match the strategic pressures and priorities that are being placed on the firm. Firms can do this in a variety of ways, but they must consider the appropriateness of each of these approaches and in turn balance them with the other enabling elements with the strategic process.

Case study

‘No business as usual’

In British Petroleum's principal area of upstream activity in the North Sea, drastic reductions in development costs had become imperative if the region was to continue to attract oil company investment in an increasingly competitive global market. BP recognized that advances in offshore technology alone would not achieve the company's commercial targets; a fundamental cultural shift in the oil industry's traditional and often adversarial contracting relationships was also essential to break through the cost barrier.

To serve as the breakthrough challenge, BP selected the Andrew field, an oil discovery that for 20 years had refused to show positive economics. The question now was, would a new way of working provide the necessary boost in business performance and drive Andrew to commercial development?

Together with its partners, BP formed a pioneering alliance in 1993 with seven contracting companies to develop Andrew's offshore production facilities. Focused on a common business goal, the alliance resolved to step away from the constraints of ‘business as usual’ in its quest to transform Andrew into a valued producing asset. Corporate alignment to the challenge came through the sharing of risks and rewards, where company profits were firmly tied to the project's financial outcomes. For individuals, the opportunity to work in a unified team with the freedom to question conventional solutions unlocked previously untapped potential for innovation and cooperation.

The power of the alliance was to surprise even its most ardent supporters by the unexpected magnitude of commercial success that it came to deliver, surpassing all anticipated levels of performance to set new benchmarks for the industry!

Key questions

1 What is the difference between purchasing as a tactical function, and supply as a strategic process?

2 Assume you are a consultant and have been asked to help in the development of a tactically focused purchasing organization to a strategically focused supply process. How might you approach this task? What do you see as the key problem areas?

3 Explain the different sourcing structures that can be used. Which structures should be used in which situations?

4 Discuss the concept of appropriateness within the supply wheel. What is meant by strategic alignment?

Lean supply management

‘Mega’ suppliers

Single, multiple, delegated and parallel strategies

Strategic supply wheel

Strategic Transition model

Supply structure and design

Transition position matrix

References

Cousins, P. D. (1999). An investigation into supply base restructuring. Eur. J. Purchasing Supply Man., 5(2), 143–55.

Cousins, P. D. (2000). Supply base rationalisation: myth or reality?’ Eur. J. Purchasing Supply Man., 3(4), 199–207.

Ellram, L. and Carr, A. (1994). Strategic purchasing: a history and review of the literature. Int. J. Purchasing Materials Man., Spring, 23–35.

Harland, C., Lamming, R. and Cousins, P. (1999). Developing the concept of supply strategy. Int. J. Production Operations Man., 19(7), 650–73.

Kraljic, P. (1983). Purchasing must become supply management. Harvard Bus. Rev., 5, 109–17.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy. Free Press.

Reck, R. F. and Long, B. G. (1988). Purchasing: a competitive weapon. Int. J. Purchasing Materials Man., Fall, 2–8.

Richardson, J. (1994). Parallel sourcing and supplier performance in the Japanese automobile industry. Strategic Man. J., 14, 339–50.

Wickens, P. (1987). The Road to Nissan. Macmillan.

Further reading

Browning, J. M., Zabriskie, N. B. and Heullmantel, A. B. (1983). Strategic purchasing planning. J. Purchasing Materials Man., Spring, 19–24.

Burt, D. and Doyle, M. (1994). The American Keiretsu: A Strategic Weapon for Global Competitiveness. Irwin.

Burt, D. and Soukup, W. R. (1985). Purchasing's role in new product development. Harvard Bus. Rev., Sep–Oct, 90–96.

Caddick, J. R. and Dale, B. G. (1987). The determination of purchasing objectives and strategies: some key influences. Int. J. Physical Dist. Materials Man., 17(3), 5–16.

Cousins, P. D. (1997). Partnership sourcing: a misused concept. In: Strategic Procurement Management in the 1990s: Concepts and Cases, (R. Lamming and A. Cox, eds), p.35–43.

Cox, A. (1996). Relational competence and strategic procurement management. Eur. J. Purchasing Supply Man, 2(1), 57–70.

Farmer, D. and Van Ploos, A. (1993).Effective Pipeline Management. Gower Publications.

Hines, P. (1994). Creating World Class Suppliers: Unlocking Mutual Competitive Advantage. Pitman Publishing.

Hines, P., Cousins, P., Lamming, R. et al. (2000). Value Stream Management. Financial Times Publications.

Lamming, R. (1993). Beyond Partnerships: Strategies for Innovation and Lean Supply. Prentice-Hall.

Lamming, R. and Cox, A. (1997). Managing supply in the firm of the future. Eur. J. Purchasing Supply Man., 1, 53–62.

Laneros, R. and Monckza, R. M. (1989). Co-operative buyer–supplier relationships and a firm's competitive strategy. J. Purchasing Materials Man., 25(3), 9–18.

MacBeth, D. and Ferguson, N. (1994). Partnership Sourcing: An Integrated Supply Chain Approach. Pitman Publishing.

Nishiguchi, T. (1994). Strategic Industrial Sourcing: The Japanese Advantage. Oxford University Press.

Saunders, M. (1994). Strategic Purchasing and Supply Chain Management. Pitman Publishing.

Speckman, R. (1989). A strategic approach to procurement planning. J. Purchasing Materials Man., Winter, 3–9.

St. John, C. and Young, S. (1991). The strategic consistency between purchasing and production. Int. J. Purchasing Materials Man., Spring, 15–20.