CHAPTER

World-class operations

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The national origins of the Fortune Global 500 companies have changed dramatically over the past few years. The list is now more international in scope, with Russia and China among the countries now represented that would not have been included a few years ago. Although certain countries continue to be associated with certain industries (Italy with fashion and design, for example), other countries have emerged as leaders in industries or industry segments. For example, India has become a leader in technology, specifically software development. India's movie industry, ‘Bollywood’, even competes with American productions in some markets. Another new star is Brazil, as Industry Week (1998a, p. 48) pointed out:

In South America, Sao Paulo, Brazil, unmistakably is the industrial standout community, a place that really matters for manufacturing. But the rest of South America, or Central America, or the Caribbean cannot be cavalierly dismissed. In Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and elsewhere in Brazil, there are pockets with the potential to be world-class manufacturing communities.

Existing companies must continuously improve in order to compete with these emerging new competitors, as having been in business many years counts for nothing in highly competitive industries.

Harvard Professor Michael Porter (1980) suggested that firms could compete either on cost leadership or differentiated capabilities, but this is no longer enough. The key responsibility for operations managers today is ensuring that the operation can compete in a globally competitive environment, through managing all of the key competitive factors (such as low cost, quality and delivery) simultaneously.

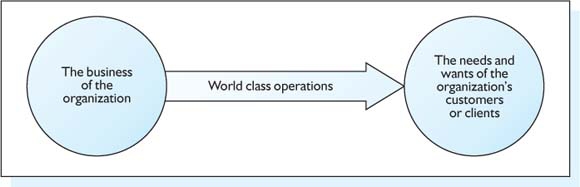

Being world class in operations capabilities is thus crucial to survival. When Richard Schonberger wrote World Class Manufacturing in 1986, ‘world class’ implied being better than other competitors. However, by 1996 Rosabeth Moss Kanter's book World Class defined world class as the level of capabilities required to compete at all today: world class has become an order-qualifying criterion.

Aims and objectives

Aims and objectives

This chapter explores world-class operations. After reading this chapter you will be able to:

![]() Explain what world-class operations means today

Explain what world-class operations means today

![]() Describe the importance and limitations of lean production

Describe the importance and limitations of lean production

![]() Identify the role of human resource management, innovation and quality in world-class operations

Identify the role of human resource management, innovation and quality in world-class operations

![]() Describe how firms have reconfigured themselves to enhance operations capabilities

Describe how firms have reconfigured themselves to enhance operations capabilities

![]() Explain how linkages with other firms contribute to world-class operations

Explain how linkages with other firms contribute to world-class operations

![]() Identify the importance of ethical and environmental considerations in operations.

Identify the importance of ethical and environmental considerations in operations.

IS LEAN PRODUCTION THE SAME AS WORLD CLASS?

IS LEAN PRODUCTION THE SAME AS WORLD CLASS?

Chapter 2 introduced mass customization, flexible specialization, lean production, agile manufacturing and strategic operations as terms that have been proposed for the era of operations that has succeeded mass production.

Lean production, one of the most popular terms, was introduced by Krafcik in 1988, and popularized in The Machine that Changed the World (Womack et al., 1990) and Lean Thinking (Womack and Jones, 1996).

The authors claim that lean practices will ultimately spread to all types of manufacturing (Womack et al., 1990, p. 12):

. . . the adoption of lean production, as it inevitably spreads beyond the auto industry, will change everything in almost every industry – choices for consumers, the nature of work, the fortune of companies, and, ultimately, the fate of nations

and further that (p. 278):

. . . lean production will supplant both mass production and the remaining outposts of craft production in all areas of industrial endeavor to become the standard global production system of the twenty-first century.

The lean producers studied in The Machine that Changed the World achieved a 2 : 1 advantage over non-lean producers. Lean producers are said to use half the time to develop new automobile models, and lean plants to be twice as productive as non-lean plants. Lean working practice, explains Dankbaar (1997, p. 567):

makes optimal use of the skills of the workforce, by giving workers more than one task (multiskilling), by integrating direct and indirect work, and by encouraging continuous improvement activities (quality circles). As a result, lean production is able to manufacture a larger variety of products, at lower costs and higher quality, with less of every input, compared to traditional mass production: less human effort, less space, less investment, and less development time.

Lowe et al. (1997, p. 785) emphasized the lean production's link between the worker, quality, and productivity in lean production, saying that (emphasis added):

A central claim made by ‘lean’ proponents is that manufacturing performance in the form of labour productivity and product quality is dramatically improved by the synergistic pursuit of these ‘lean’ production practices in conjunction with flexible multiskilling work systems and high commitment human resource policies . . . Furthermore, lean production management practices are advanced as a universal set of best practices which yield performance benefits at the establishment level, regardless of context and environment

Whether lean production can be transferred from the automotive industry to other industry sectors needs further exploration. Cook (1999, p. 15) suggests that the aerospace industry is one such possibility:

Lean aircraft designers consider that a new ‘right first time’ culture in aerospace manufacturing will do for aircraft what it did for the car industry a decade ago. Under the new regime, panels and components damaged in operation can be quickly replaced at the front line without special customization in much the same way that car parts are ordered up and fitted in the commercial world. Employees involved in all aspects of Eurofighter production – from the design stage through to logistic support – are grouped in integrated product teams (IPTs). Each IPT is responsible for its own budget and accountable for its particular section of the aircraft.

In the USA, Lockheed Martin's Aeronautics sector declared 1999 ‘the year of lean’, applying lean practices to the F-16 and F-22 fighter programmes and the C-130J military transport aircraft. Lockheed's executives have declared their commitment to lean (Industry Week, 1998b, p. 43):

‘Lean manufacturing is not a one-time event’, notes an executive at Lockheed Martin Corp.’s 11 000-employee Ft. Worth plant that builds military fighter aircraft. ‘It is a systematic and continual refinement of processes over an extended period of time’.

In the USA and the UK, it is said ( Flight International,1999, p. 10):

The aerospace industry is in the grip of a revolution. Its name is ‘lean’ and its guiding principle is the elimination of waste from the production cycle. The revolution is moving out of the prototyping shops and on to the assembly lines, with dramatic results – and none too soon. The automotive industry has been lean for years. In aerospace, avionics and engine manufacturers embraced lean thinking long before the airframe makers. Now airframers are moving fast to catch up. Their motivation is the promise of faster development, better quality and lower cost.

Are world-class operations and lean production synonymous? Critics of lean production point to its effects on the workforce. For example, Delbridge (1998), in Life on the Line in Contemporary Manufacturing, argues that the benefits of team working and empowerment are largely mythical. Similarly, Niepce and Molleman (1998, p. 260) suggest that:

In our view, the leading coordination mechanism in LP is the standardization of work processes . . . Instead of having freedom as to when to work, workers have to adhere to the fixed pace as the reduction of inventory buffers makes workers increasingly dependent on work-flow time-sequencing that is governed by the technology employed . . . Teams are not autonomous but are built around the supervisor, a strong hierarchical leader who commands the team and carries the responsibility for the team's activities.

Similar criticisms have been made of Lockheed's lean initiatives (Manufacturing News, 2000, p. 3):

‘Lockheed's version of lean manufacturing isn't with employee empowerment,’ says Terry Smith, a business representative with the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (LAM) at the Ft. Worth plant. ‘Their version of lean manufacturing is more top down where they say, “We want you to do it this way so we can figure out how to do it cheaper and with less people.”’

Brown (1996, 1998) suggests that lean production ignores four critical operations areas:

1 Manufacturing's strategic role. Manufacturing's explicit contribution to corporate planning is ignored within lean production. In Japanese plants this role is both central and explicit, which creates strategic resonance (Chapter 2).

2 Manufacturing strategy. Lean production ignores manufacturing strategy itself, which links corporate planning and operations strategy. In Japanese firms, manufacturing strategy feeds into and forms an essential part of corporate strategy.

3 The seniority of production/operations staff. Lean production ignores the link between operational performance and operations involvement at senior levels within the firm. In Japanese and, to some extent, German organizations, senior production/operations managers help set the agenda at the board level for key internal and external factors. These factors include the nature, scope and extent of horizontal strategic alliances; strategic partnerships with suppliers; commitment to training; ongoing, lifetime commitment to quality; and investment in process technology.

4 Horizontal alliances. The major role of horizontal partnerships is ignored within lean production, although the importance of vertical relationships in achieving lean supply is discussed.

So, whilst lean practices are important, they are only part of world-class operations. In particular, lean production neglects a key input into world-class operations – human resources.

THE IMPORTANCE OF HUMAN RESOURCES, QUALITY, AND INNOVATION IN WORLD-CLASS OPERATIONS

THE IMPORTANCE OF HUMAN RESOURCES, QUALITY, AND INNOVATION IN WORLD-CLASS OPERATIONS

The operations manager's responsibilities, as shown in Chapter 1, include managing people. Firms must get the very best out of their workforces, because passion, commitment, vision and new ideas come from people, not technology. However, this is difficult today because of the increased uncertainty about jobs in both manufacturing and service organizations. The era of the ‘job for life’ is past, due to mergers, acquisitions, and downsizing within firms. The old message of ‘join us and have a job for life’ has been replaced by ‘we can't offer you a job for life, but we can train you so that you are a lot more employable as a result of working for us’. Workers must continuously enhance their skills to stay employable, or be left behind, as Davis and Meyer (2000, p. 12) propose in their book FutureWealth:

You must realize that how you invest your human capital matters as much as how you invest your financial capital. Its rate of return determines your future options. Take a job for what it teaches you, not for what it pays. Instead of a potential employer asking, ‘Where do you see yourself in 5 years?’ you'll ask, ‘If I invest my mental assets with you for 5 years, how much will they appreciate? How much will my portfolio of career options grow?’

During the mass production era machine operators received little or no training, since work was very repetitive and required little or no skill under the ‘machine-type’ approach to work. Today, workers are exhorted to be flexible, multiskilled and highly trained.

Peter Drucker, the influential management writer, has commented that (Business 2.0, 2000):

Knowledge becomes obsolete incredibly fast. The continuing professional education of adults is the No. 1 industry in the next 30 years . . . mostly on line.

The consequences on a national level are described by Richard Rosecrance in The Rise of the Virtual State (1999, p. 22):

At the ultimate stage, competition among nations will be competition among educational systems, for the most productive and richest countries will be those with the best education and training.

However, corporate initiatives such as ‘right-sizing’, ‘downsizing’ and ‘focus’ have shed operations workers, often in large numbers. It has been argued that this can result in a ‘corporate lobotomy’, where the essential expertise and know-how on which core competences depend are lost with these workers. The Economist (1995, p. 6) stated that:

In the end, even the re-engineers are re-engineered. At a recent conference held by Arthur D. Little, a consultancy, representatives from 20 of America's most successful companies all agreed that re-engineering, which has been tried by two-thirds of America's biggest companies and most of Europe's, needs a little re-engineering of its own . . . As well as destroying morale, this approach leads to ‘corporate anorexia’, with firms too thin to take advantage of economic upturns.

Downsizing in recent years has been dramatic. In 1995 AT&T announced that it was reducing the workforce by 40 000 employees, adding to the 140 000 it shed during the decade following deregulation in 1984. Wall Street responded to the announcement by boosting the company's shares. For employees, though, the 1995 announcement was painful, because AT&T was prospering and the salary of AT&T's CEO, Bob Allen, had just been increased to $5 million per year. Other dramatic reductions during the 1990s included 50 000 at Sears, 10 000 at Xerox, 18 000 at Delta, 16 800 at Eastman Kodak and 35 000 at IBM. IBM alone shed 100 000 jobs between 1990 and 1995. In 1998, General Motors announced that it would close a number of domestic factories, shed jobs and eliminate models in an effort to become more competitive. GM's North American sales and marketing operations would be reduced to a single division, thereby reducing bureaucracy, costs and jobs. The downsizing phenomenon has become evident in the new millennium, with horrific headlines such as the following appearing (New York Times, 2000, p. 3):

Bank of America to Cut . . . 10 000 Jobs. . . Middle-level and senior managers are expected to be the principal targets of the job cutbacks.

Lean approaches have been misunderstood as getting rid of staff in order to make the organization lean, which instead results in it not being able to function properly. Driving down costs, a key ingredient of lean production, does not mean simply getting rid of people. Drastic downsizing can result in corporate amnesia, where a great deal of knowledge goes with the staff and can't be replaced. Some large firms have had to rehire staff on a consultant or contractor basis, often at an increased salary!

Sometimes companies have little choice but to downsize, but downsizing takes little or no skill and is at best a short-term solution. As Kanter (1996) pointed out, the real skill in downsizing lies in managing the process so that the remaining staff are committed to operations, including quality and innovation. World-class operations can reduce costs through reducing throughput time, improving layout, and enhancing quality through ‘right first time, every time’ approaches.

The role of quality and innovation in world-class operations

The role of quality and innovation in world-class operations

Why did quality emerge as a strategic factor in Western firms during the 1980s and 1990s? Two key factors are:

1 The number (and capabilities) of new entrants, which increased competition between new and existing companies, all of whom must compete to ‘world-class’ standards

2 The increasing choice available to customers, again largely due to new entrants.

Many firms have become blasé about quality, as Hamel (1998, p. 23) notes:

The challenge is no longer quality; nor is it globalization. You've been there, done that, got the ISO 9001.

However, firms cannot afford to give up on quality, since continuous improvement is an integral feature of world-class quality. Quality is important for any firm in the public or private sector, and achieving quality certification or implementing a quality initiative does not mean that the firm can relax.

World-class quality makes no distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ quality – quality is no longer associated with ‘high-end’ market tastes, but is measured by each particular customer segment within the overall market. Each segment may differ in its needs and requirements, and the firm must identify these requirements and then provide customer satisfaction through world-class operations capabilities. Meeting customer requirements may mean competing on cost or any other competitive variable. In some industries customer satisfaction may be the minimum requirement, and the firm may need to ‘delight’ the customer instead. Tom Peters (1991, 1992) has described this as going beyond customer satisfaction to ‘customer success’, quoting Bob Nardelli of GE Power Systems as saying:

We're getting better at [Six Sigma] every day. But we really need to think about the customer's profitability. Are customers’ bottom lines really benefiting from what we provide them?

World-class firms pay attention to quality areas that other firms either neglect or consider unimportant. Such attention to detail can provide advantages. For example, Federal Express transports parcels and other packages around the world, making its top objective on-time delivery. However, Federal Express goes beyond this to being obsessive about customer response times. Their ability to answer incoming telephone calls has become legendary. Good service is usually considered answering the telephone within three rings: Federal Express can actually answer before the first ring, although it has installed a cosmetic first ring to reassure customers who found this un-nerving.

Another example is Walt Disney Corp., which is highly successful in operating theme parks. A not-so-obvious quality issue is, as Tom Peters described in one of his seminars in 1990:

Everybody can copy Disney's technology in theme parks; nobody else can figure out how to keep the damn park clean!

Keeping the park clean, Peters suggests, is fundamental to Disney's success. Other important factors in world-class quality (Brown, 2000) include never giving up on quality, instead of saying ‘we have done quality’ after being certified under ISO 9000 or receiving a quality award. World-class operations is also about getting better in those areas where the organization already excels, as well as actively seeking out new and non-obvious areas of improvement, as at Federal Express and Disney.

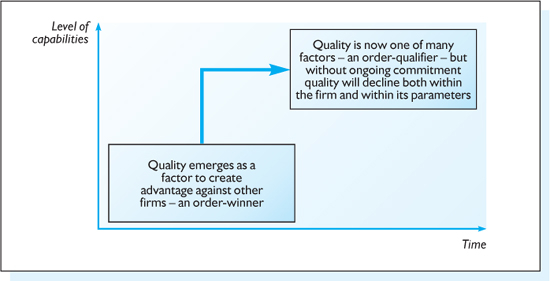

Figure 11.1 World-class operations and quality

Figure 11.1 illustrates world-class quality.

For world-class quality, the following factors need to be in place.

Top management commitment, both in terms of ‘setting an example’ and in terms of their willingness to invest in training and other important features of TQM. Juran's (1993) account of his contribution to the Japanese quality revolution provides important insight into the process of spreading the quality message throughout Japanese firms:

The senior executives of Japanese companies took personal charge of managing for quality. The executives trained their entire managerial hierarchies in how to manage for quality.

However, as seen in Chapter 2 and previously pointed out in the discussion on lean production, this may prove a problem for firms that have no senior-level operations managers in place who might help to champion the cause of quality within the organization.

Continuous improvement. Deming, Juran, Crosby and other quality ‘gurus’ may have different views in their actual approaches to and prescriptions for quality. However, what becomes a common denominator, both for the ‘quality gurus’ and for firms involved in quality, is that quality is a ‘moving target’, and therefore a firm must have a strategic commitment to always improve performance. ‘Signposts’, in terms of amounts of rejects and scrap, act as guidelines rather than as a completed goal. A firm must continuously improve and go from, for example, percentage defects to parts per thousand, then parts per hundred thousand and so on, committed to reducing defects, as a way of life. As seen in Chapters 7 and 8, any organization has to strive to improve its performance in operations.

Quality in all aspects of the business. Quality relates to all personnel within the firm and also outside, including all aspects of the supply chain and other strategic partnerships. One of Deming's statements was that managers should ‘drive out fear’ from the workplace. In the current age of electronic commerce and virtual organizations, the same rule applies. Quality has to pervade all relationships within various networks in which the organization is involved.

Long-term commitment. Total quality management is not a ‘quick-fix’ solution. Rather, it is an everlasting approach to managing quality. This long-term commitment is probably the most difficult challenge for many organizations. There can often be a tendency to ‘wear the T-shirt’ or display an award or accreditation in quality. Once an achievement in quality has been made, the temptation is to relax. However, in the conditions of hyper-competition in which many markets now operate, ongoing commitment to continuous improvement is a key requirement in order to compete.

World-class operations and innovation

World-class operations and innovation

As Professor John Kay stated in The Foundations of Corporate Success, innovation is one of the very foundations of corporate success. Tom Peters (1991) says this more succinctly: ‘Get innovative or get dead’. A survey of global manufacturing executives by consultants Deloitte and Touche found that product innovation was seen as driving growth and customer retention (Industry Week, 1998c). Gary Hamel (1998) points out that today we fly with Virgin Atlantic (founded in 1984), purchase computers from Dell (founded in 1984), and buy insurance from Direct Line (founded in 1985), none of which existed 20 years ago, concluding that:

Never has the world been a better place for industry revolutionaries; and never has it been a more dangerous place for complacent incumbents.

It has also never been more important to have world-class innovation capabilities. Being first to market does not necessarily sustain success, because in many cases ‘followers’ have outperformed first entrants. For example, whilst Pilkington (float glass), Polaroid (instant cameras), Corning (fibre optic cable) and Procter and Gamble (disposable diapers) have stayed market leaders, EMI (X-ray scanner), Ampex (VCRs), Bowmar (pocket calculators) and Xerox (with both PCs and plain paper copiers) have been outperformed by ‘market followers’ who had world-class innovation capabilities.

Likewise, the inability to innovate has major repercussions. Over 50 per cent of the firms listed in the Fortune 500 in 1985 have now disappeared. As the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1939) first noted, innovation can lead to creative destruction of entire industry sectors, in which existing firms are replaced by new entrants due to changes in products, technology, supply or organization.

The rate of innovation has also had an impact on everyday life. As the British Medical Journal (1999) puts it:

Medicine looks likely to change more in the next 20 years than it has in the last 200.

World-class innovation requires capabilities beyond operations. Innovation is a difficult and uncertain process, whose success is only known after the event, as can be seen from the following (Yates and Skarzynski, 1999, p. 16):

‘Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?’ said Hollywood mogul H. M. Warner in 1927. Equally notorious was Ross Perot's retort when colleagues suggested in 1980 that EDS buy an upstart company named Microsoft: ‘What do 13 people in Seattle know that we don't know?’ complained Perot.

However, world-class operations are necessary for successful innovation. Some firms have put world-class operations in place and then forgotten the reasons behind their success. Breakthrough innovation often comes not from large, incumbent organizations, but from new entrants pioneering innovations that may be related but are not necessarily specific to an existing industrial sector. As Chandy and Tellis (2000, p. 21) state:

One lesson from stories of corporate innovation is that it's rare for incumbent firms in an industry to reinvent that industry. Leadership in the typewriter industry, for example, changed hands from Remington to Underwood to IBM (with the ‘golf-ball’ typewriter) to Wang (with the advent of word-processing) and now to Microsoft. Never once did the leader at a particular stage pioneer the next stage.

This incumbent's curse, the authors argue, results when incumbents in a particular product generation are so enamoured by their past success or so restricted by their bureaucracy that they fail to develop the next generation of new products. Hamel (1998, p. 22) states:

Of course, there are examples of incumbents like Coca-Cola and Procter & Gamble that are able to continually reinvent themselves and their industry, but all too often, industry incumbents fail to challenge their own orthodoxies and succumb to unconventional rivals.

Small-and medium-sized companies can seize major opportunities when this happens, because companies tend to develop inertia as they age and grow in size. ‘Bureaucratic inertia’ (Tornatzky and Fleisher, 1990) results from more levels of screening and group decision-making, diluting individual contributions, so that innovators are less likely to see their efforts resulting in actual innovations. Large firms must ensure that their operations capabilities fully support the innovation process from the very early, concept development stages. This is often hard, because success can create arrogance. At one time IBM lost its ability to translate patents into final products via operations capabilities. This had significant repercussions (Hamel, 1998, p. 16):

When, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, IBM unwittingly surrendered its historic role as the architect of industry transformation, it also surrendered billions of dollars in future wealth creation.

So the key issue for large firms is to ensure that their operations capabilities fully support, and are involved in, the innovation process from the very early, conceptual stages. This is often harder to do than first appears, because successes can be the cause of arrogance (Markides, 1998. p. 31):

Successful companies ‘know’ that the way they play the game is the right way. After all, they have all those profits to prove it. Not only do they find it difficult to question their way of doing business, but also their natural reaction is to dismiss alternative ways even when they see competitors trying something new. For example, it took Xerox at least twenty years to recognize Canon as a serious threat and respond. It took Caterpillar even longer to face up to Komatsu.

As Geoff Yang from Institutional Venture Partners (IVP) points out, in-house innovation prioritizes speed:

It used to be that the big ate the small. Now the fast eat the slow.

(quoted in Tom Peters Seminar, 2000).

GEO's Chief Executive Officer, Jack Welch, echoed this sentiment in Forbes (2000, p. 28):

One cannot be tentative about this. Excuses like ‘channel conflict’ or ‘marketing and sales aren't ready’ cannot be allowed. Delay and you risk being cut out of your own market, perhaps not by traditional competitors but by companies you never heard of 24 months ago.

Chapter 3 showed how firms have introduced a range of techniques to improve the innovation process. Many firms also outsource some of the innovation process. Quinn (2000, p. 13) discusses the benefits of outsourcing:

Leading companies have lowered innovation costs and risks 60% to 90% while similarly decreasing cycle times and leveraging the impact of their internal investments by tens to hundreds of times. Strategic management of outsourcing is perhaps the most powerful tool in management, and outsourcing of innovation is its frontier.

World-class operations must choose partners and manage the relationships with these partners. Chapter 5, discussing strategic supply, explains why this can be difficult. Where firms have retained much of their innovation process in-house, they have had to reconfigure the organization to enable world-class innovation.

An important breakthrough strategy for solving the design/operations gap in mass production is the development of product platforms, to ensure communication and cooperation from the concept development stage of product development. Platforms link various functions in the innovation process, but sometimes this needs to be supported by organizational change. For example, in 1991 Ford created the Design Institute, whose charter was to ‘change the fundamental way of doing our design, development, and manufacturing’. Although the Ford Taurus had been the best-selling car in the USA between 1992 and 1997, Ford had to change its approach radically at the end of the 1990s. Former CEO Alex Trotman argued that (Ward's Automotive Year Book, 1998, p. 66):

The economies of scale that come from purchasing materials from a simplified buying list, the single manufacturing system, the benefits of using best practice worldwide, all those things hold true [but] what is a big issue is the number of platforms you have, how many drivelines, and how many people you have designing those products.

Ford has responded to increasing pressures for globalization by introducing ‘world cars’ designed around a single (or very small number of) platforms that can be sold in multiple regions. The idea of the world car is to share best practice among various divisions and plants, as well as trying to gain scale economies. Thus far, Ford's world cars have not been successful. In the early 1980s, the Ford Escort's American and European platforms did not share enough common components, and Ford lost money on the Escort. The more recent Mondeo/Contour/Mystique world car also lost money, even with 70 per cent common components. As Standard and Poor's Industry Survey (1999, p. 56) stated:

. . . while the rationale for building a world car is straightforward, the ability to do so successfully is not. For example, local tastes, infrastructure, government regulations, and other factors may make it difficult for a manufacturer to keep variations to a minimum.

Similarly, Renault fundamentally reorganized its development process, bringing together in the Renault Technocentre 7500 engineers, designers and supplier staff who had been formerly split between different Parisian locations. Renault intended to reduce its R&D spending by FFr1 billion per year, and to reduce product development times to 24 months (Brown, 2000).

Prior to the merger between Daimler and Chrysler, Daimler's design centre brought together personnel previously housed in 19 different sites. Helmut Petre, the group head of passenger car development, explained the rationale (Financial Times, 1998, p. 6):

We will become much faster in processes – although speed for itself was not our first aim . . . Product development has already got 30 per cent faster, but we see scope to do more.

Japanese auto firms had been held up as exemplars of fast innovation in the 1980s, but fell behind in the early 1990s. Honda in particular struggled, but has made a major turnaround (Fortune, 1996, p. 33):

Honda, the fairy-tale come-from-nowhere auto success of the Eighties, suddenly started falling apart in the early Nineties when the Japanese economy sank back to reality. Business dried up . . . The sport-utility boom? Honda missed it – completely. The company lost its famous sense of Japanese tastes. Honda's car sales fell in 1993 and again in 1994. Yet now, just two years later, Honda is zooming ahead of competitors to enjoy the greatest success of its 48-year history. [CEO] Kawamoto says that before the bubble burst, ‘Honda was in tune with the times. Everything it did was a roaring success. Then the environment changed, and we had to change the organization’.[qr] (Fortune, Sep 9, 1996: p33).

Honda's success was based not only on a particular product development but also on organization-wide change and redevelopment – organizational reconfiguration. This brought benefits in resources and speed. Honda has not yet matched Toyota, though (Fortune, 1997, p. 25):

Like everything else at Toyota, product development is changing too . . . Two years ago Toyota reorganized its engineers into three groups – front-wheel-drive cars, rear-wheel-drive cars, and trucks . . . In the past two years it has introduced 18 new or redesigned models, including the new Corolla, which is made in different versions for Japan, Europe, and the US. Several Japanese models, like the Picnic and the Corolla Spacio, went into production as little as 1412 months after their designs were approved – probably an industry record. Toyota also caught the auto world napping by announcing a breakthrough in engine design. The 120-horsepower engine in the 1998 Corolla uses 25% fewer parts than its predecessor, making it 10% lighter, 10% more fuel-efficient, and significantly cheaper.

At Toyota, innovation is not only evident in the surge of new models (18 in two years), but also in the complete redesign of engines and other major components. The deliberate redesign of the organization to support innovation challenges firms who think that a radical cultural change will take place around a particular new product.

Toyota's innovation capabilities rely on the company's engineers. As Sobek et al. (1998, p. 39) observe, at Toyota manufacturing personnel are pivotal to the innovation process (emphasis added):

Some of the remaining integration problems at US companies may in fact stem from a lack of precisely this kind of system design. Even companies with able heavyweight product managers tend to jump directly from product concept to the technical details of engineering design. They bypass, without going through, the very difficult but important task of designing the overall vehicle system: planning how all the parts will work together as a cohesive whole before sweating the fine details. At Toyota, the chief engineer provides the glue that binds the whole process together.

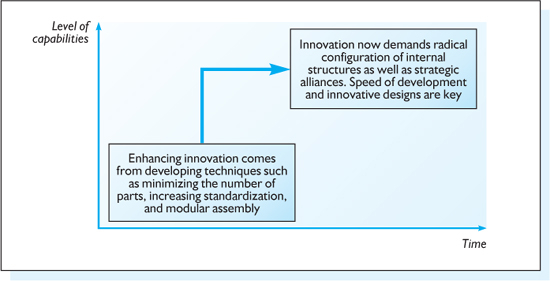

For some firms, the idea that senior staff members should be involved in strategic areas such as innovation is a problem that needs to be overcome if they are to attain success in world-class operations. The role of world-class operations in innovation is shown in Figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2 World-class operations and innovation.

HOW FIRMS RECONFIGURE THEMSELVES TO BECOME WORLD-CLASS

HOW FIRMS RECONFIGURE THEMSELVES TO BECOME WORLD-CLASS

A highly qualified and dedicated workforce is only one facet of world-class operations, whether a firm competes in premium markets where high prices can be charged or in price-sensitive markets, since organizations depend on operations capabilities to drive down costs.

Mass production did not permit world-class operations capabilities to emerge. Under mass production, many corporations adopted the multidivisional form identified by Chandler (1962), with the firm arranged by divisions around functional groupings. Under this arrangement the manufacturing division might be in one place and the sales division in another, often far apart. Innovation became a protracted process. The cross-functional teams described in Chapter 3 are one way of partly overcoming this.

Many firms have had to reorganize themselves fundamentally in order to become world-class in a range of operations capabilities. This sometimes, but not always, entails downsizing. The ‘virtual organization’ is an example of radical reconfiguration.

Drucker suggests that profound changes are taking place (Business 2.0, 2000, p. 13):

The corporation as we know it, which is now 120 years old, is not likely to survive the next 25 years. Legally and financially, yes, but not structurally and economically.

Other writers have also commented on this. Rosencrance (1999, p. 35) said:

The virtual corporation is research, development, design, marketing, financing, legal, and other headquarters functions with few or no manufacturing capabilities – a company with a head but no body

and the following was published in Forbes (2000, p. 67):

More and more companies these days want to be like Cisco. They want to focus on their core business and outsource all the superfluous stuff, like human resources, procurement and accounting.

Even in the virtual corporation, however, operations managers are still responsible for coordinating the remaining ‘core’ activities so that world-class operations are in place.

WORLD-CLASS OPERATIONS, MERGERS AND ALLIANCES

WORLD-CLASS OPERATIONS, MERGERS AND ALLIANCES

Chapter 2 mentioned strategy's military origins. It makes sense to ensure that ‘enemies’ become ‘friends’ or ‘allies’ in world-class operations, as in the relationships and alliances that have happened in many industries. This only confirms the military analogy – one group clusters together against other, competing alliances (or clusters), all of which are seeking to position themselves and gain some sort of defensive cover or competitive advantage.

As Brown (2000, p. 34) explains, forming alliances is directly relevant to world-class operations:

In order to be a contender as a player within these alliances, a would-be partner has to demonstrate some unique or outstanding operations capability that another partner does not have. Clearly, world-class performance in operations has profound, strategic importance for firms in terms of alliances. Such alliances will be formed between world-class firms, who possess outstanding, and complementary, capabilities.

Alliances are common in many industries, due to a large extent to two factors:

1 Fewer companies have the resources to enter into mergers and acquisitions than in the relatively cash-rich 1960s and 1970s. Many firms cannot ‘go it alone’ in R&D, and alliances let them collaborate with others, as Dussauge et al. (1992, p. 127) observe:

Not all alliances are technology-based but in a majority of cases, technology is a key element . . . About two-thirds of all strategic alliances can be considered as technology-based.

2 Mergers and alliances have not proved successful for many companies, and alliances are an alternative, as are forming strong buyer–supplier relationships throughout the supply chain.

For manufacturing firms, the benefits of alliances are first allowing the firm to concentrate on core manufacturing activities, and second becoming a means of organizational learning. Types of alliances include:

![]() Licensing agreements

Licensing agreements

![]() Joint ventures

Joint ventures

![]() Franchising

Franchising

![]() Marketing agreements/dual marketing

Marketing agreements/dual marketing

![]() Buyer–seller relationships (particularly in JIT production)

Buyer–seller relationships (particularly in JIT production)

![]() Consortia

Consortia

![]() Research and development alliances

Research and development alliances

![]() Joint access to technology and markets.

Joint access to technology and markets.

Firms enter alliances for two purposes:

1 To create advantage for the firms involved in the alliance

2 To act as a defensive mechanism against firms who have entered competing agreements.

Such alliances have become commonplace in the auto industry. As seen in Chapter 6, a key issue for the industry is over-capacity; another 20 million more cars and trucks could be produced per year with current resources. The Asia-Pacific region alone will add capacity for 6 million cars by 2005. One forecast is that by the year 2010 the current 40 carmakers will have been reduced to a ‘Big Six’(Business Week, 1999):

By 2010, the thinking goes, each major auto market will be left with two large, home-based companies – GM and Ford in the US, Daimler– Chrysler and Volkswagen in Europe, and Toyota and Honda in Japan. Players such as Nissan or Volvo may keep their brand names, but someone else will be running the show.

In telecommunications, a number of alliances were put in place essentially to deal with major technological uncertainties. These alliances have included Concert, involving BT and MCI; Global One, which consisted of Deutsche Telekom, France Telecom, Sprint and partners; and WorldPartners/Unisource, made up of AT&T, Telecom Italia, KPN of the Netherlands, the Swiss PTT, Telia of Sweden, Telstra of Australia, and Singapore Telecom. Such alliances have major consequences on operations because they are often designed to result in end products, the speed, volumes and mix of which are ultimately determined by operations capabilities.

Thus world-class operations are important in alliances and merger activities for at least two reasons. First, being world-class means that firms have the potential to be linked with other world-class firms to form important, powerful alliances. Second, world-class operations capabilities may be threatened if the supposed benefits of the alliance or merger do not create strategic fit between two or more firms’ operations capabilities Mergers and acquisitions do not always enhance operations and supply capabilities. For example, the 1999 Daimler–Chrysler merger created the world's fifth-largest car company, but the strategic fit is difficult. Chrysler purchases 70 per cent of its added value from mainly American suppliers, and came closer than GM or Ford to lean production standards. By contrast, Daimler is a fully integrated German luxury car producer. After the merger, Daimler–Chrysler reviewed the entire component supply chain in Europe and North America to improve strategic fit, but this may well threaten Chrysler's strategic relationships with suppliers.

THE ROLE OF ETHICS IN WORLD-CLASS OPERATIONS

THE ROLE OF ETHICS IN WORLD-CLASS OPERATIONS

Ethics should be considered in world-class operations, as well as being discussed in business ethics and corporate responsibility areas. First, ethical issues are often created at the operations level, particularly in the transformation process – ‘on the production line’. Second, outsourcing and ‘virtual organizations’ are often pursued to gain cost advantages, but have ethical consequences.

Ethics and operations management

Ethics and operations management

In the USA, manufacture and distribution of firearms has created heated debate at various government levels. When Smith & Wesson, the nation's largest handgun manufacturer, agreed with federal, state and local governments to restrict the sale of handguns (Singer, 2000):

The National Rifle Association and the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) denounced Smith & Wesson for ‘selling out’ the industry and called for an immediate boycott of the company's products.

Quality has emerged as the operations topic most closely related to ethical issues. For example, when a high rate of accidents with Ford sports utility vehicles (SUVs) equipped with Firestone tyres was revealed, Ford released its first-ever ‘corporate citizenship’ report, a 98-page document called Connecting with Society. The report highlighted two serious problems with SUVs: first, SUVs pollute the air and consume petrol at rates far higher than conventional automobiles; and second, SUVs are hazardous to other vehicles!

Roger Cowe's article ‘The rise of the virtuous company’ mentions how (Cowe, 2000):

There is a tension between profits and responsibilities, between marketing or cost-cutting and exploitation. But selling one Hawk jet to Indonesia instead of ten does not make it responsible. Nor does it become acceptable to employ children if you double their pay. The tension does not really stem from how much profit is enough (whether you are a bank, and oil company or a supermarket chain). It is about how the profit is made, rather than how much profit piles up or how much is given away. This gets to the heart of what responsible business is about – issues such as child labour, human rights, animal welfare, armaments, genetic engineering and pollution.

Table 11.1 Examples of ethical issues in operations management (source: Business Week, 2000)

US company/product |

Factory/town |

Labour problems |

Huffy bicycles |

Baoan Bicycle, Shenzhen, Guangdong |

15-hour shifts, 7 days a week. No overtime pay |

Wal-Mart |

Qin Shi Handbag |

Guards beat workers for being late |

Kathie Lee Handbags |

Zhongshan, Guangdong |

Excessive charges for food and lodging mean some workers earn less than 1 cent an hour |

Stride Rite |

Kunshan Sun Hwa Footwear |

16-year-old girls apply toxic glues with bare hands and toothbrushes |

Keds Sneakers |

Kunshan, Jiangsu |

Workers locked in factory behind 15-ft walls |

New Balance Shoes |

Lizhan Footwear, Dongguan, Guangdong |

Lax safety standards, no overtime pay as required by Chinese law |

In May 2000, the New York-based National Labor Committee reported findings of abusive conditions in 16 Chinese factories randomly selected from those to whom American factories had outsourced manufacturing operations. A summary of these is found in Table 11.1.

Such working conditions are clearly not acceptable. However, some firms seek out every means of competitive advantage, including outsourcing activities and then abdicating responsibility for monitoring labour conditions in low-wage countries. Business Week (2000, p. 4) highlights this ethical issue:

Investigators for US labor and human-rights groups estimate that Asia and Latin America have thousands of sweatshops, which do everything from force employees to work 16-hour days to cheat them out of already meager wages, that make products for US and European companies. ‘It would be extremely generous to say that even 10% of [Western companies charged with abuses] have done anything meaningful about labor conditions,’ says S. Prakash Sethi, a Baruch College business professor who helped set up a monitoring system for Mattel at its dozen factories in China, Indonesia, Mexico, and elsewhere.

Business ethics encompasses more than exploitation of workers; it also concerns the means of exchange between buyer or consumer and suppliers of particular products. For example, H. B. Fuller enjoyed a reputation as one of the USA's most socially responsible companies, endowing a Chair in Business Ethics at the University of Minnesota and ‘establishing a charitable foundation dedicated to the environment, the arts, and social programs’ (Singer, 2000). However:

. . . beginning in the late ’80s, the company was dogged by reports that one of its adhesives, Resistol, had become the drug of choice for glue-sniffing street kids in Central America . . . H. B. Fuller seemed unprepared for the furore that arose over the abuse of one of its products. ‘It's a social problem. It's not a product problem,’ the company argued. Still, it pulled the product off retail shelves in Guatemala and Honduras.

Organizations that claim to be ethical can set themselves up for criticism. The Body Shop shows how firms can change working practices and deal with a range of ethical issues. However, the company has been criticized in the media for its practices. In the UK, for example, an hour-long television programme on Channel 4 questioned the Body Shop's practices on animal testing, as well as probing investments in projects in underdeveloped areas. Professor Norman Bowie, of the London Business School warns (Singer, 2000):

If you do something ethical, and then market it, and there's a little failure, you get hammered.

Michael G. Daigneault, president of the non-profit Ethics Resource Center in Washington, D.C., adds that (Singer, 2000):

The irony . . . is that a lot of these organizations have the best intentions, and many actually walk the talk – 99 percent of the time. But the 1 percent of the time that they slip up, someone will be waiting for them.

Environmental responsibility and operations management

Environmental responsibility and operations management

Whether environmental systems and environmental performance lead to higher corporate performance is far from clear. The quality saying ‘do things right first time, every time’ does imply less waste. Some authors (for example, Makower, 1993, 1994; Porter and Van der Linde, 1995) suggest that becoming more environmentally responsible means that firms uncover new sources of waste and so enhance their productivity, so that enhanced environmental responsibility leads to improved business performance. Other writers (such as Walley and Whitehead, 1994) argue that in most cases improved environmental performance actually reduces profits and shareholder value.

However, this is not the whole of ethical issues. The need to document business responsibility has become important. ISO 14000 was introduced in 1996, in response to demand for a single international environmental standard. It was developed by an international technical advisory committee of industry, government, consumer interest groups and the general public. The scope of environmental issues is defined in the standard as:

Surroundings in which an organization operates, including air, water, land, natural resources, flora, fauna, humans and their interrelation. The environment in this context extends from within an organization to the global system.

ISO 14000 sets standards in seven general areas:

1 Environmental management systems

2 Environmental auditing

3 Environmental performance evaluation

4 Environmental labelling

5 Life cycle assessment

6 Environmental aspects of product standards

7 Terms and definitions.

Just as ISO 9000 certifies that a quality documentation system is in place and being adhered to, ISO 14000 certifies that an environmental management system is there. ISO 14000 combines the quality certification aspects of ISO 9000 with preventive environmental management. Many companies objected to the paperwork associated with ISO 9000, and ISO 14000 requires written documentation of policies and procedures for only four or five instances. In addition, ISO 14000 builds on the administrative elements of ISO 9000 where that system is already in place (such as in document control and record keeping systems).

Montabon et al. (2000, p. 15) suggest that being environmentally responsible should pervade the supply chain:

Being environmentally responsible is increasingly viewed as a requirement of doing business. For manufacturing managers, this has meant re-examining their products and processes, with an eye toward the reduction or elimination (if possible) of any resulting waste streams. For the purchasing profession, the corresponding challenge has been to identify suppliers who can provide environmentally responsible goods and services without sacrificing cost, quality, flexibility, or lead-time. It has also meant identifying and evaluating any initiative consistent with these new expanded objectives. One such initiative is ISO 14000.

ISO 14000 has had a global impact. In Malaysia, for example, 96 companies from the manufacturing sector registered with Sirim Bhd for ISO 14000 certification, and although this is only a few of the more than 700 manufacturing companies in Malaysia, more are expected to attempt certification (Business Times (Malaysia), 1999, p. 23). In Brazil, Cosipa, a major iron and steel producer, has been certified, and has signed a letter of intent with the Sao Paulo environmental agency SMA to deal with its pollution problems.

There are many valid reasons why firms register for ISO 14000 certification. First, customers are increasingly demanding environmental management systems be in place, as Xerox Corp. found. A 1995 survey of 99 US businesses considering ISO 14000 implementation found that 50 per cent reported customer demand or competitive advantage as reasons to pursue certification (Graff, 1997). Companies in European and Asian countries are demanding ISO 14000 registration. For example, China has adopted ISO 14000 as state policy. Major US automobile manufacturers expect first-tier suppliers to have environmental management systems. Other global corporations are making similar demands on suppliers, including in the pulp and paper industry (Graff, 1997). Just as ISO 9000 became important in industries from health care to the military, ISO 14000 will become an important order-qualifier for organizations.

Tibor and Feldman (1996) suggest that the following situations lead to ISO 1400 registration:

![]() A customer requires certification as a condition to sign a contract

A customer requires certification as a condition to sign a contract

![]() An organization supplies to a customer who strongly suggests you become registered

An organization supplies to a customer who strongly suggests you become registered

![]() A government provides benefits to registered organizations

A government provides benefits to registered organizations

![]() A firm has a site in the European Union, where market pressure or the regulatory environment forces you to obtain registration or certification

A firm has a site in the European Union, where market pressure or the regulatory environment forces you to obtain registration or certification

![]() A single international environmental standard can reduce the number of environmental audits conducted by customers, regulators, or registrars.

A single international environmental standard can reduce the number of environmental audits conducted by customers, regulators, or registrars.

![]() A firm exports to markets where EMS registration is a de facto requirement for entering the market.

A firm exports to markets where EMS registration is a de facto requirement for entering the market.

![]() A firm expects to gain a competitive advantage through EMS registration.

A firm expects to gain a competitive advantage through EMS registration.

![]() The organization's stakeholders (local community shareholders, unions etc.) expect environmental excellence, and an EMS registration is the way to demonstrate it.

The organization's stakeholders (local community shareholders, unions etc.) expect environmental excellence, and an EMS registration is the way to demonstrate it.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

Being world-class in operations capabilities is crucial to survival, because world-class has become an order-qualifier rather than an order-winner. Lean production is not synonymous with world class (although lean practices are part of world-class operations), because it neglects a key input into world-class operations – human resources. All the things that make business exciting come from people, not machines, and downsizing can lead to a ‘corporate lobotomy’ or ‘corporate amnesia’.

Firms have fundamentally reorganized themselves to become world class in a range of operations capabilities. Quality in world-class firms is about never giving up on quality, getting better in the areas where the firm already excels, and actively seeking out areas of improvement that do not appear to be important on the surface. Innovation is also a major requirement for firms, although being first to market does not necessarily bring sustained success. World-class firms must also chose partners in a range of areas, and manage relationships with them. Enemies must become friends or allies as part of world-class operations.

Finally, business ethics and corporate responsibility are part of world-class operations. This responsibility is likely to increase, as awareness in major ethical and environmental issues becomes greater.

Japan Inc.

Introduction

The case study in Chapter 1 looked briefly at Toyota. This chapter ends with an overview of Japan's successes via its operations management capabilities, which enabled many companies within Japan to become world class.

In 1945 many of Japan's cities and factories were reduced to little more than rubble. Goods of all kinds, including food, were scarce. Inflation was running at around 100 per cent per year. The major economic transformation began in about 1949, and was greatly dependent upon a range of operations capabilities that were performed simultaneously to very high standards. The term ‘economic miracle’ is one that best describes the remarkable attainments in manufacturing and trade that the Japanese people achieved in the decades after World War II..

When the American market was opened to Japan in the 1950s, very few people could have anticipated Japan's extraordinary economic growth, via the high quality of its products, or the competition it would pose to American manufacturers. Indeed, the danger to Japan, as Americans became concerned about an imbalance of trade, was over-dependence on the USA as a market for its goods. Many Japanese companies have become household names: Sony, Panasonic, Toshiba, Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Fujitsu, Mitsubishi, Canon, Hitachi and many others.

The manufacturing focus

In 2000, slightly less than 25 per cent of Japan's labour force was employed in manufacturing. Most Japanese manufacturing units comprise small workshops, often family-owned and employing only very few workers. Factories employing more than 300 workers – which are less than 1 per cent of the total number – account for about 50 per cent of Japan's industrial production. Conversely, about 60 per cent of the workers are in firms that employ fewer than 100 people.

The Japanese became the leading makers of electronic equipment, such as radios and television sets, calculators, microwave ovens, watches and photocopiers. Japan is also a leading producer of industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, chemical fertilizers, and petrochemical products, such as plastics, synthetic fibres and synthetic rubber. Japanese oil-refining capacity has grown to the third largest in the world. Japan is also a major world producer of cement. Large amounts of Japanese-made plate glass, firebrick, asbestos products, fibreboard and other construction materials find application within the nation's fast-growing cities.

The Japanese iron and steel industry, vital to the development of all manufacturing, grew spectacularly in the 1950s. By the mid-1950s, Japan was building 50 per cent of the world's new shipping. This industry went into a slump from the 1970s, and has never made a full comeback. South Korea proved to be a strong competitor, and shipping suffered from over-capacity around the world. Five corporations accounted for more than 80 per cent of Japan's steel output.

Japan's abilities in manufacturing were based upon a range of capabilities described in previous chapters.

Making best use of limited resources

This is a recurring theme in this book, and has been used largely within the focus of a single organization. In Japan's case it was a whole nation that had limited resources! However, Japan's short supply of natural resources did not prove to be a limiting factor on productivity. The country lacks oil, which is the basic mineral for modern industry, and most of its petroleum comes from the Middle East. Its coal is of poor quality and the supply of iron is small, while lead, zinc, potassium and phosphates must be imported. A large amount of food is also imported.

All of these factors were against Japan. However, the ability to add value to its raw materials as they are turned into finished products meant that Japan's economy grew despite natural shortages. What made the difference were world-class capabilities in managing supply (Chapter 5) and quality (Chapter 8), and extraordinary capabilities in managing and implementing strategy, which resulted in synchronization between customer demand and operations output – through just-in-time (Chapter 7).

Strategy

The main strategy behind the Japanese miracle has been aggressive exporting of manufactured goods to gain market share around the world. For many Japanese manufacturers, the strategy was to expand market share at the expense of immediate profit. They were often willing to let profits be minimal for some time – even to post a loss – in order to gain customers. The shareholders, being mainly banks, were not concerned with receiving dividends from profits.

A powerful strategy for dealing with fears over exports was in the creation of transplants in key foreign sites in the USA, Europe and Latin America. Another reason for this practice was a diminished supply of manual labour within Japan. Developing countries, such as Indonesia and Thailand, had large numbers of manual labourers available. By 1991, Japan had direct foreign investment of more than 81 billion dollars. Clearly, such investment is not restricted to Japan. However, it is Japan that has made the most dramatic use of this strategy.

Alliances

Many large manufacturing firms formed enterprise groups called keiretsu, which are bound together through mutual stockholding and interlocking directorates. These close relationships involve manufacturing firms and the banks that are their major sources of funds. This means that ownership of corporations is much more concentrated in Japan than in the USA, since banks hold most of the shares of a company. The keiretsu also maintain relationships with smaller firms. The large manufacturers of machinery, for example, have ties to specific small workshops. These workshops receive subcontracts for work and parts from the big firms. The keiretsu are basically oligopolies – a few large firms and their associated subcontractors.

Innovation

The success of Japanese manufacturing owes much to the willingness of their businesses to innovate. In the 30 years after 1950, Japanese corporations made more than 30 000 licensing and other technology agreements with other nations. A famous example was in 1952 when Akio Morita and Masaru Ibuka, who had started a company named Tokyo Telecommunications and Engineering, heard of an American invention called the transistor. Bell Laboratories in the USA had invented this electronic device in 1947, but American manufacturers saw little immediate potential for it. The two Japanese businessmen paid $25 000 for a licence to use the transistor and within 2 years were producing transistor radios. They named the little radios Sony, and soon that became the corporate name.

The changes from the 1990s

By the early 1990s, the Japanese economy, especially manufacturing, found itself in a new global environment. By the 1980s, industrialization had expanded in previously underdeveloped areas, notably in Far Eastern countries. These were providing competition for Japan in its export trade, and labour costs in these countries were much less than in Japan.

The partial breakdown of the keiretsu system provided the basis for another trend in the economy – entrepreneurship, the starting up of new privately owned business ventures. The notion of entrepreneurship – starting a new business – had not been nearly as common in Japan as it has long been in the USA. In the 1990s, however, a number of universities started teaching courses on how to operate one's own business. Numerous ventures were started and met with great success.

Japan is no longer the only economic powerhouse in Asia. South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore (collectively called the Four Little Tigers) have very robust economies. South China was experiencing astounding growth, and there were predictions that it would become the world's largest economy by 2010.

Undoubtedly there have been major mistakes made on a financial level in Japan. However, nobody can assume that all of the world-class operations capabilities that many Japanese firms have accrued over time are now worthless. Indeed, the very foundations on which Japan's future rests will depend upon these world-class capabilities in operations management.

1 Why has the term ‘world-class’ changed in meaning over time?

2 Why is managing human resources a particularly difficult task in the modern era?

3 In what ways can operations managers play an important role in ‘ethical’ factors within an organization?

Key terms

Business ethics

ISO 1400

World-class operations

References

British Medical Journal (1999). 11 November, p.12.

Brown, S. (1996). Strategic Manufacturing for Competitive Advantage – Transforming Operations from Shop Floor to Strategy. Prentice Hall.

Brown, S. (1998). Manufacturing strategy, manufacturing seniority and plant performance in quality. Int. J. Operations Product. Man., 18(6), 565–87.

Brown, S. (2000). Manufacturing the Future – Strategic Resonance for Enlightened Manufacturing. Financial Times Books.

Business 2.0 (2000). 22 August.

Business Week (1999). 25 January.

Business Times (Malaysia) (1999). 2 November.

Business Week (2000). 6 November.

Chandler, A. (1962). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Irwin.

Chandy, R. and Tellis, G. (2000). The incumbent's curse? Incumbency, size, and radical product innovation. J. Marketing, 64(3), 1–12.

Cook, N. I. (1999). The race is on in lean production. Interavia Bus. Technol., 54, 15–20.

Cowe, R. (2000). The rise of the virtuous company. The New Statesman, 6 November.

Dankbaar, B. (1997). Lean production: denial, confirmation or extension of sociotechnical systems design? (Special issue: Organizational Innovation and the Sociotechnical Systems Tradition). Human Relations, 50(5), 567–84.

Davis, S. and Meyer, C. (2000). FutureWealth. Harvard Business School Press.

Delbridge, R. (1998). Life on the Line in Contemporary Manufacturing. Oxford University Press.

Dussauge, P., Hart, S. and Ramanantsoa, B. (1992). Strategic Technology Management. Wiley.

Economist (1995). 9 September. Financial Times (1998). 3 December.

Flight International (1999). September.

Forbes (2000). 27 July.

Fortune (1996). 9 September.

Fortune (1997). 8 December.

Graff, S. (1997). ISO 14000: should your company develop an environmental management system? Industrial Man., 39(6), 19–33.

Hamel, G. (1998). The challenge today: changing the rules of the game (importance of non-linear innovation). Bus. Strategy Rev., Summer, 18–29.

Industry Week (1998a). 6 April.

Industry Week (1998b). 21 September.

Industry Week (1998c). 6 July.

Juran, J. (1993). Made in the USA: a renaissance in quality. Harvard Bus. Rev., Jul–Aug, 42–50.

Kanter, R. (1996) World Class. Simon and Schuster

Kay, J. (1993). Foundations of Corporate Success. Oxford University Press.

Krafcik, J. F. (1988). Triumph of the lean production system. Sloan Man. Rev., 30(1), 12–25.

Lowe, J., Delbridge, R. and Oliver, N. (1997). High-performance manufacturing: evidence from the automotive components industry. (Special Issue on Organizing Employment for High Performance). Organization Studies, 18(5), 783–99.

Manufacturing News (2000). 10 April.

Makower, J. (1993). The Bottom Line Approach to Environmentally Responsible Business. Times Books.

Makower, J. (1994). Beyond the Bottom Line. Simon & Schuster.

Markides, C. (1998). Strategic innovation in established companies. Sloan Man. Rev., 39(3), 31–43.

Montabon, F., Melnyk, S., Sroufe, R. and Calantone, R. (2000). ISO 14000: assessing its perceived impact on corporate performance. J. Supply Chain Man., 36(2), 14–23.

Niepce, W. and Molleman, E. (1998). Work design issues in lean production from a sociotechnical systems perspective: neo-Taylorism or the next step in sociotechnical design? Human Relations, 51(3), 259–88.

New York Times (2000). 29 July.

Peters, T. (1991). Get innovative or get dead (part 1). Eng. Man. Rev., 19(4), 4–11.

Peters, T. (1992). Get innovative or get dead (part 2). Eng. Man. Rev., 19(5).

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy. Free Press.

Porter, M. E. and Van der Linde, C. (1995). Green and competitive – ending the statement. Harvard Bus. Rev., Sep–Oct, 120–34.

Quinn, J. B. (2000). Outsourcing innovation: the new engine of growth. Sloan Man. Rev., 41(4), 13–28.

Rosecrance, R. (1999). The Rise of the Virtual State. Basic Books.

Schonberger, R. (1986). World Class Manufacturing. Free Press.

Schumpeter, J. (1939). Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process. McGraw-Hill.

Singer, A. (2000). The perils of doing the right thing. Across the Board, 37(9), 14–19.

Sobek, D. K., Liker, J. K. and Ward, A. (1998). Another look at how Toyota integrates product development. Harvard Bus. Rev., 76(4), 36–48.

Standard and Poor's Industry Survey: Automobiles (June) (1999). McGraw-Hill.

Tibor, T. and Feldman, I. (1996). ISO 14000: A Guide to the New Environmental Management Standards. Irwin Professional Publishing.

Tornatzky, L. G. and Fleisher, M. (1990). The Process of Technological Innovation. Lexington Books.

Walley, N. and Whitehead, B. (1994). It's not easy being green. Harvard Bus. Rev., May–Jun, 46–52.

Ward's Automotive Year Book (1998). Intertec Publishing Group.

Womack, J. and Jones, D. (1996). Lean Thinking. Simon and Schuster.

Womack, J., Jones, D. and Roos, D. (1990).The Machine That Changed the World. Rawson Associates.

Yates, L. and Skarzynski, P. (1999). How do companies get to the future first? Man. Rev., Jan, 16–29.