CHAPTER

Operations management: content, history and current issues

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Who comes to mind when you think of successful organizations? Perhaps Amazon.com for their level of customer service, Nokia or Sony for their innovative electronics, Toyota for their reliable automobiles, Dell for their ability to customize PCs to individual requirements, Andersen Consulting for their brand image, Sky TV for the variety of television programmes available, or McDonald's for sheer ubiquity, come to mind. These companies – or others you may have thought of – have come to dominate their market segments through offering the best goods or services, or have provided you with product or service that you think is excellent.

High-recognition firms like these are heavily marketed and constantly brought to our attention. Marketing hype alone isn't enough, however, to create excellence – organizations have to deliver on their promises or face disillusioned (and, increasingly, litigious) customers. In each case, the organization cannot be excellent without excellent operations. This is true for all organizations – those that help and protect us, such as hospitals, fire, police, ambulance and coastguard emergency services; those who provide general public services, such as schools, public utilities, transportation, and universities; and those who provide goods and services to customers and other organizations. Operations are at the forefront of service delivery in each case.

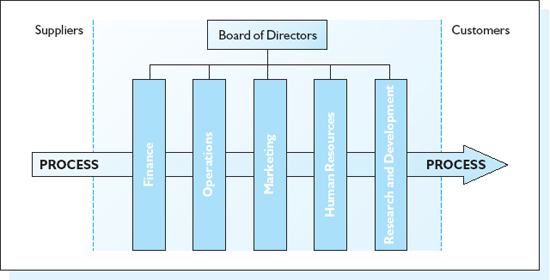

Successful operations management contributes substantially to organizational success or failure: operations is where, to use a metaphor, ‘the rubber hits the road’. Imagine what would happen if Sega took too long to develop their next computer game – their old games would be made obsolete by new games from competitors and wouldn't sell, and the company would quickly cease to exist. Similarly, the pizzeria that takes twice as long to deliver your pizza as expected, or the accountant who makes mistakes with your taxes, will soon go out of business. Operations is vitally important because it links what the business does with the needs and desires of the organization's customers or clients, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Linking the business of the organization with customers via operations.

The role of operations has become increasingly important in recent times, because the needs and wants of customers and clients have increased. This was described in a book called Funky Business (Ridderstrale and Nordstrom, 2000, p. 157):

Let us tell you what all customers want. Any customer, in any industry, in any market wants stuff that is both cheaper and better, and they want it yesterday.

We'd probably all agree with that statement, but we tend to take it for granted how products are made better, cheaper and more quickly than before. The point is that all of these are achieved by operations capabilities, and that's why operations are so vitally important for businesses today.

Aims and objectives

Aims and objectives

Welcome to the world of operations management. Most of us probably think of operations management as having little to do with our lives and work, but each of us comes constantly into contact with aspects of operations management every day.

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the nature of operations and operations management today, and to:

![]() Define operations, operations management, and operations managers

Define operations, operations management, and operations managers

![]() Explore the history and context today of operations management

Explore the history and context today of operations management

![]() Introduce you to the key concepts and ideas that this book will cover.

Introduce you to the key concepts and ideas that this book will cover.

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

![]() Describe the role of operations in different sorts of organizations

Describe the role of operations in different sorts of organizations

![]() Show how operations management is relevant to organizations, managers and individuals

Show how operations management is relevant to organizations, managers and individuals

![]() Explain how operations managers bring together different contributions to satisfy customers.

Explain how operations managers bring together different contributions to satisfy customers.

The next section begins with a formal definition of operations, and then introduces some basic concepts for describing and analysing operations. Next, the roles and responsibilities of operations managers are described more fully. Succeeding sections consider the limits to operations management, its usefulness, and how operations management can help people manage complex organizations in highly competitive environments. The chapter closes with a brief overview of the important themes to be covered in this book, and presents a model for bringing all of these themes together.

WHAT IS OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT?

WHAT IS OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT?

Every organization has an operations function, whether it is explicitly called operations or not. A traditional view of operations is that it is:

Those activities concerned with the acquisition of raw materials, their conversion into finished product, and the supply of that finished product to the customer (Galloway, 1998, p. 2).

Another way to think about operations is that operations is what the company does. To identify the role of operations with an individual organization, ask the question, ‘what do you do?’ Amazon.com might answer that question with ‘we sell books and other goods on-line’. Isn't selling different from operations? In this case no, because here selling involves the operations of transferring the ownership of products from the retailer to the buyer. Amazon.com's front-line sales process works so well that the company's customers come back over and over again. A hospital treats patients, and so we might ask: ‘isn't that medicine?’ It is, but if you look beyond the doctors and nurses who treat patients, a whole organization exists to supports their work – facilities management, staffing, catering and so on. All of this comes under the responsibility of operations management. So it's important to bear in mind that operations take place throughout an organization. It's often impossible to speak of operations taking place in just one specific area. Operations will take place in different ways in the entire organization and, as you'll see throughout the book, we will provide ways for you to understand the nature of the operations taking place in each case.

Within organizations, operations management describes the functional area responsible for managing the operations that produce the organization's goods and services for internal or external customers or clients. Operations management gives us a way of thinking about operations that helps us design, manage and improve the organization's operations in an orderly fashion. Operations managers are the people who design, manage and improve how organizations get work done.

A key aspect of operations management is that it focuses on processes. A definition of processes is, as Hewlett Packard describes, ‘the way we work’. Due to the significant role that processes play in operations, operations managers frequently use tools and techniques developed for analysing processes, and we shall see a range of these in the book.

Operations management also describes the academic study of the different operations practices used by organizations. In this context, operations management draws lessons from organizational success and failures and makes those lessons available to students and managers. Studying operations management gives us the tools to analyse the operations of an individual organization or groups of organizations and to prepare them to compete in the future.

The study of operations management is highly relevant to whatever work you do or plan to do. Most managers are involved in some aspect of operations every day, but many never realize it. Familiarity with operations enables managers to manage their responsibility better, whether they are directly responsible for the organization's goods and service outputs or not.

Similarly, studying operations management is useful for all management students, because you can apply operations concepts to everyday aspects of your study and work activities. Also, because operations management is at the core of what any organization does, it has important connections with other functions including marketing, human resource management and finance

Policies, practices and performance: the four ‘P's of operations management

Policies, practices and performance: the four ‘P's of operations management

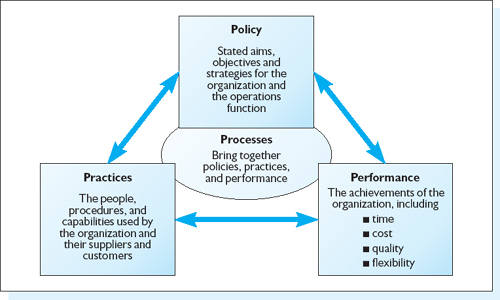

Operations managers manage processes via the four ‘P's of operations: Policies, Practices, Processes and Performance. Figure 1.2 defines each ‘P’ and shows the relationship between all of them. The four key elements and their relationships are described below.

Policies are the stated aims, objectives and strategies for the organization including operations. Policies are based on the desired state of affairs that an organization wants to achieve. The organization's mission statement has an important part in articulating the organization's policy. Strategy is concerned with how the organization will get there. Policies define the practices – the systems, procedures and technological capabilities – that need to be in place within the organization, and between the organization and its suppliers and customers. Policies cannot be realized without the support of appropriate practices. For example, the American department store Nordstrom's is famous for its policy of providing a high level of customer service at all times. This might require the store to employ additional staff to make sure that someone is always available to serve customers.

Figure 1.2 The four ‘P's of operations management.

Policies also need to be aligned with performance. Performance describes how the organization does in terms of time, cost, quality and flexibility. Where there are gaps between policy and the desired level of performance, operations managers need to make improvements in order to close these gaps.

Performance is strongly linked to practices. For example, by adopting modern Japanese management practices such as just-in-time (described in Chapter 7), many organizations have improved their operations performance – including reducing space, lowering inventory levels and achieving faster throughput times – which, in turn, has lead to better financial results such as improved cash flows. Modern organizations continuously change their practices to improve their performance because, as we shall see in Chapters 2 and 11, the business environment is more competitive than ever before.

Both policies and practices determine what performance measures will be important. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) such as customer service time, cost or quality provide feedback to the operations function and to the whole business as to how well operations is performing.

World-class, high-performing organizations explicitly link the four ‘P's’, making their effects clear. Only a few organizations can claim to be in this class – less than 2 per cent of all organizations (Voss et al., 1997). On the other hand, most organizations only have weak links between the ‘P's’, as we will discuss further in Chapter 2.

Models of operations

Models of operations

Earlier, we mentioned how operations management includes transforming various inputs into outputs. These inputs and outputs will include tangible and intangible elements. In a factory, processing materials and stages of production are clearly evident; however, the transformation process from inputs into finished ‘products’ is not so obvious in many service operations. Even so, service organizations (including banks, hospitals, social services and universities) all transform inputs into outputs. Here we shall differentiate between the task that operations carry out in terms of the transformation process, and the task of an operations manager in bringing together all the necessary elements to enable the process to take place.

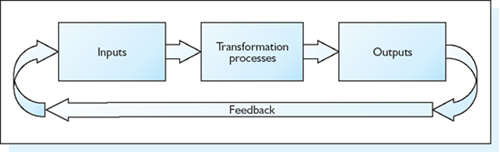

Operations are concerned with those activities that enable an organization to transform a range of inputs (materials, energy, customers’ requirements, information, skills and other resources) into outputs. These are different for manufacturing and for service organizations. A basic inputs/outputs model is shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Basic transformation model.

As you can see from Figure 1.3, feedback plays an important role for operations managers. Such feedback enables managers to make improvements and to enhance the quality of goods and services provided for customers and clients. The feedback mechanism is an important one for operations managers, and can come from both internal and external sources. Internal sources will include testing, evaluating and continuously improving processes and products; external sources will include others involved in supplying to end customers as well as feedback from customers themselves. This basic model can be used in manufacturing and service environments, and in both private and public sectors.

The service transformation

The service transformation

Service operations generally transform information, people or animals, physical items or ownership. Examples of each of these transformations are given in Table 1.1.

The manufacturing transformation

The manufacturing transformation

For a manufacturing firm, the transformation process is more obvious. Materials are processed, changing their form. The materials may take a number of forms and determine the nature of the transformation process. Typically, an operation may be a raw material producer, a user of raw materials, combining or changing them into parts, which are then assembled by another operation into assemblies or finished goods. Examples of each of these are given in Table 1.2.

Table 1.1 Examples of service transformations

Transformed input |

Example |

Nature of transformation |

Information |

Graphic design firm |

Ideas or outlines are transformed into detailed designs or layouts |

|

Accountant |

Data in the form of financial records is ordered into the required form, calculations made and recommendations provided |

People |

Restaurants |

A hungry person is transformed into someone who is fed |

|

Airline |

The location of the person is transformed |

Physical items |

Car service |

A car in need of work being performed on it has this carried out |

|

Logistics firm |

Moves goods from one place to another |

Ownership |

B2B or wholesale operation |

The ownership of goods is transferred from one party to another |

|

Car hire |

The use of the vehicle is temporarily transferred from the hire company to the hirer |

Table 1.2 Examples of manufacturing transformations

Transformed input |

Example |

Nature of transformation |

Extracted products |

Steel producer |

Iron ore is the extracted product, and through a series of processes is converted into steel |

Raw material |

Silicon chip producer |

Wafers of silicon are processed into chips |

|

Cloth printer |

Rolls of cloth from the mills are transformed by the addition of dyes through the printing process |

Parts |

Washing machine assembly |

All the parts from different suppliers (mechanical, electrical and electronic) are assembled into final products |

|

Drink bottling |

The bottle, cap, label and liquid contents are all ‘parts’ of the finished product and are combined in the bottling process |

The one-way flow in the transformation model is only one of the flows that occur around operations. Other flows include:

![]() Revenue – flowing from customers back down the supply chain to suppliers

Revenue – flowing from customers back down the supply chain to suppliers

![]() Information – passing both ways from product/service providers to customers and in feedback from customers to the providers.

Information – passing both ways from product/service providers to customers and in feedback from customers to the providers.

Although this model is often used and can provide some basic insights into the nature of operations, we argue that operations management in the modern era is more complex than this suggests. This is because, as we shall see throughout this book, operations management is no longer limited to a narrow, organization-specific activity. One further problem of the transformation model is that it focuses on the ongoing nature of day-to-day operations. The reality is that operations usually take place in an environment in which little stays constant for long.

Having defined the function that operations perform in terms of the transformation process, it is now necessary to consider the role that operations managers play. They have a day-to-day management role, which consists of controlling the processes for which they have responsibility. This is simply maintaining the system in a state of acceptability. The real area where truly excellent operations managers make a difference is in their ability to design and continuously improve their processes. For this the transformation model is inappropriate, and so we propose the dynamic convergent model. Its main feature is that it represents the ‘change’ aspects of the operations managers’ task, which take an increasing proportion of their time.

A dynamic convergent model of the role of operations managers

A dynamic convergent model of the role of operations managers

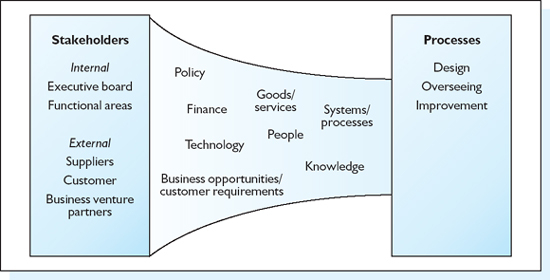

Now that we have looked at manufacturing and service operations, we can define in more detail the role of operations managers. Operations managers are responsible for managing the process of convergence that delivers goods and services to end customers or clients. Specifically, the operations manager brings together resources, knowledge and market opportunities. Resources are the people, physical resources and finances of the organization and its suppliers. The role of suppliers has become increasingly important recently, and the role of supply is therefore discussed in depth in Chapter 5. Knowledge comprises the experience of people within the organizations, their systems and processes, including the information technology infrastructure. Market opportunities are the customer needs, which are then translated into a set of deliverables by operations.

Operations managers perform three integrative key tasks in the convergence process (see Figure 1.4):

1 The design of the organization's products, the outputs of goods and services, and the processes by which they are created and delivered

2 The management of the day-to-day aspects of operations, making sure that work is performed, dealing with problems that arise, and liaising with other parties in order to make sure that operational objectives are achieved

3 The ongoing improvement of the operations process, through analysing existing ways of working, and developing and implementing improvements to particular performance aspects, in order to prevent problems from occurring or recurring.

The improvement aspect has been the centre of recent attention, particularly in globally competitive industries such as the automotive and electronics sectors. The best performing organizations today continuously improve their processes.

The stakeholders can potentially make any one of the contributions listed to the process.

The role of the operations manager is to select and integrate the contributions in order to design or develop the process. For example, during the expansion of their call-centre operations a leading telephone insurance brokerage needed to bring together a number of key stakeholders including:

Figure 1.4 The convergent model of the role of operations managers.

![]() Suppliers of the technology to run their IT and telephone equipment

Suppliers of the technology to run their IT and telephone equipment

![]() The insurance companies whose products were being offered

The insurance companies whose products were being offered

![]() Financiers who would pay for the expansion

Financiers who would pay for the expansion

![]() Staff who would run the new expanded systems

Staff who would run the new expanded systems

![]() Customers, who through focus groups showed the firm their preferences for doing business over the telephone.

Customers, who through focus groups showed the firm their preferences for doing business over the telephone.

The operations manager united these requirements into a coherent system so that it would work not only on the first day of operation, but for several years to come.

A typology of operations

A typology of operations

If you were asked to describe an operation with which you have come into contact, how would you do this? You might describe the operation in terms of your experience with it, or its size or reputation. A number of basic elements are helpful in describing operations. The first is whether it is a manufacturing or a service operation or, as will be seen in the following section, if there are elements of each in the organization.

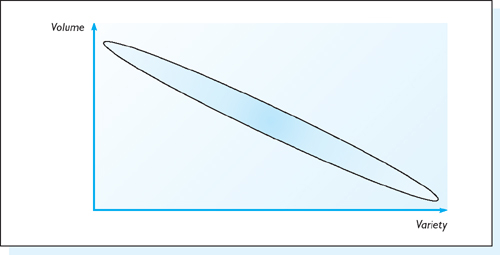

Another aspect is the nature of the process taking place. Two characteristics describe this – volume and variety. High volume products such as cars, consumer electronic devices and fast food are typical examples of this. In order to achieve what economists describe as ‘economies of scale’, these are usually produced in low variety. The number of variations of a car may be significant when considering the different body styles, engine sizes and types, colours and options available, but the reality is that the variety is limited by the choices available, and so the variety is perceived rather than actual.

Similarly, low volume products and services are generally available in a higher variety.

The relationship between volume and variety is shown in Figure 1.5, and we shall explore this in more depth in Chapter 4.

As Figure 1.5 shows, the general position of operations is along the diagonal, where the higher the volume the lower the variety and vice versa.

Supermarkets offer a high variety of products and yet sell in high volumes. Doesn't this rather change the rule? Not in this case, although there may well be examples where both are offered. The point here is that the process is the same for all customers – it is standardized. Everyone is treated in the same way – it is not tailored for the individual. Therefore, from a process perspective, the variety is low, and the general finding still stands.

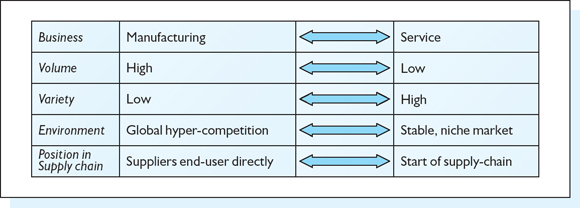

Figure 1.5 The relationship between volume and variety.

There are two other dimensions that provide insight into the nature of the operations environment in which the organization operates. The first is the degree of competition in the market for the organization's goods or services. Generally, high volume organizations operate in highly competitive markets, with many offerings competing for market share. The extreme is the mass-market for cars and computers, where global hypercompetition exists. This is not the case for all firms, as many operate in niche markets, often serving local customers. The second dimension is that of position in the supply chain or supply network. Regardless of whether an operation is manufacturing or service-based, it is part of a network or chain of activities. These may be serving end-users directly, or providing a contribution towards that directly or indirectly through their products.

In summary, the typology of operations is shown in Figure 1.6.

This classification is useful as it will tell us something about the general characteristics of the operations that we describe in this way. These are summarized in Table 1.3.

Considering the first element of this typology, manufacturing and service operations are different, yet both are important to the success of an organization. The following two sections consider the operations issues associated with each of these environments. As we have mentioned, operations management isn't just about managing manufacturing operations; service operations are equally important. We usually describe organizations that transform physical materials into tangible products (goods) as manufacturing. In contrast, organizations that influence materials, people or information without physically transforming them may be termed as service organizations.

Figure 1.6 A typology of operations.

Table 1.3 The general characteristics of operations

Task |

Manufacturing: the creation of physical products |

Service: all work not concerned with the creation of physical products |

Volume: variety |

High volume – low variety: high levels of capital investment, systemization, routinized work and flow through transformation system, resulting in low unit costs |

Low volume – high variety: usually flexible technology, people and systems performing high value-adding work resulting in high unit costs |

Environment |

Hyper-competition: organizations are pursuing any possible avenue to create competitive advantage, or simply survive |

Niche: organizations optimize existing systems to maximize return on their investment |

Position in supply chain |

Supply end customer/user: driven by needs of consumers, must integrate supply networks to deliver these needs |

Removed from final customer/user: driven by needs of intermediaries in the process, work as part of supply networks |

Although it would be much easier if we could separate organizations so neatly into manufacturing and service operations, in real life most organizations produce both services and products for their customers and only a few could be called ‘pure manufacturing’ or ‘pure services’. As noted previously, even manufactured products are now surrounded by complex and sophisticated service packages, and manufacturing organizations are being transformed into service operations surrounding a manufacturing core. For example, services such as installation, maintenance and repair and technical advice are usually provided with household appliances such as refrigerators and washing machines. Software applications such as word-processing or spreadsheet programs generally come on physical media such as floppy disks or CD-ROMs, accompanied by technical documentation manuals.

It is important to bear in mind two major differences between services and manufacturing, which are:

1 Tangibility – whether the output can be physically touched; services are usually intangible, whilst products are usually concrete

2 Customer contact with the operation – whether the customer has a low or high level of contact with the operation that produced the output.

These two factors – intangibility and customer contact – lead to other differences between manufacturing and service operations, as shown in the following list:

![]() Storability – whether the output can be physically stored

Storability – whether the output can be physically stored

![]() Transportability – whether the output can be physically moved (rather than the means of producing the output)

Transportability – whether the output can be physically moved (rather than the means of producing the output)

![]() Transferability – ownership of products is transferred when they are sold, but ownership of services is not usually transferred

Transferability – ownership of products is transferred when they are sold, but ownership of services is not usually transferred

![]() Simultaneity of production and consumption – whether the output can be produced prior to customer receipt

Simultaneity of production and consumption – whether the output can be produced prior to customer receipt

![]() Quality – whether the output is judged on solely the output itself or on the means by which it was produced.

Quality – whether the output is judged on solely the output itself or on the means by which it was produced.

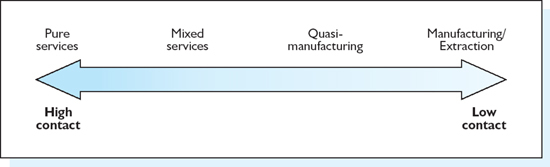

Although some aspects of the production of goods and services will differ, the operations function itself is becoming increasingly similar for goods and services. Recognizing this, Chase (1983) suggested that operations could be ranged along a continuum from pure manufacturing to pure services, with quasi-manufacturing in the middle, as shown in Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.7 The service–manufacturing continuum

Table 1.4 Typical differences between manufacturing and services (Normann, 1991)

|

Manufacturing |

Service |

Tangibility |

Product is generally concrete |

Service is intangible |

Ownership |

Transferred when sold |

Not generally transferred |

Resale |

Can be resold |

Cannot generally be resold |

Demonstrability |

Can be demonstrated |

Does not exist before purchase |

Storability |

Can be stored by providers and customers |

Cannot be stored |

Simultaneity |

Production precedes consumption |

Generally coincide |

Location |

Production/selling/consumption locally differentiable |

Spatially united |

Transportability |

Can be transported |

Generally not (but producers might be) |

Production |

Seller alone produces |

Buyer/client takes part |

Contact |

Indirect contact possible between client and provider |

Direct contact usually necessary |

Internationalization |

Can be exported |

Service usually cannot (but delivery system often can) |

Quality |

Can be inspected in situ |

Cannot be checked before being supplied |

The continuum helps us to understand where a firm's operations line up in terms of the emphasis on manufacturing or services. Another insight is provided by Normann, when he distinguishes between manufacturing and service environments under a number of key headings, as shown in Table 1.4.

Service operations

Service operations

Services experts haven't yet agreed on a definition of service operations. Some definitions of services use manufacturing operations as the norm – for example, Schroeder (1999, p. 75) gives the traditional perspective on services that they are ‘manufacturing with “a few odd characteristics”’, while Russell and Taylor (2000, p. 91) suggest that ‘services and manufacturing companies have similar inputs but different processes and outputs’. Other definitions focus on the human aspects of services, such as Normann's (1991) definition of services as ‘acts and interactions that are social contacts’, and Zeithaml and Bitner's (2000, p. 2) description of services as ‘deeds, processes, and performances’.

In this book we will define service operations as:

transformation processes in which there is a high degree of interaction between the customer and the organization, and in which the output may be primarily or partly intangible.

The importance of service operations

The importance of service operations

Service operations are an essential focus of modern operations management. Service organizations range from one-person small businesses to large, multinational corporations, including organizations in the following sectors:

![]() Business services – consulting, finance, banking

Business services – consulting, finance, banking

![]() Trade services – the distribution, installation and upkeep of physical objects, including retailing, maintenance, and repair services

Trade services – the distribution, installation and upkeep of physical objects, including retailing, maintenance, and repair services

![]() Infrastructure services – communications, transportation

Infrastructure services – communications, transportation

![]() Social/personal services – restaurants, health care

Social/personal services – restaurants, health care

![]() Public services – government and non-profit organizations, including education, health care, government.

Public services – government and non-profit organizations, including education, health care, government.

In many developed countries, more people work in services than in previously dominant sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing. Over time, employment in most developed economies has shifted, first from agriculture to manufacturing, and more recently from manufacturing to services. The proportion of people working in services in these economies has increased from about 1 in 20 in the 1880s to three in four today. This is partly due to the increase in the efficiency of other sectors. Agricultural, extractive and manufacturing industries have increased their productivity so much through the application of modern techniques that it is possible for relatively few people to produce large outputs. Consequently, in many highly developed nations the service sector accounts for most of the gross national product (GNP). As a result, the service sector contributes to economic well-being and productivity at the national and individual levels.

Even within organizations primarily engaged in agriculture, extraction or manufacturing there is a large ‘hidden’ service sector. A large part of the value created by manufacturing companies is created by service activities rather than manufacturing activities, including both internal services required to support the organization's ongoing activities and external services provided in association with products.

Responsibilities of operations managers

Responsibilities of operations managers

The operations manager often has to manage a range of responsibilities and these can be profoundly important to the competitive performance of an organization. Operations responsibilities include the management of human resources, various assets and costs. We shall look at each of these in turn.

Human resources

Human resources

A motivated, trained and skilled workforce has to be in place for any manufacturing or service operations if an organization is to compete successfully. Human resources can be closely linked with the firm's core competences. This term was devised by Hamel and Prahalad (1994), who describe core competences as ‘a bundle of skills and technologies rather than a single discrete skill or technology’. Although it is incorrect to limit core competences to human resources only, it is clear that human resource management must form at least part of the organization's core competence because ‘skills’ come from human capabilities.

Human resources are so important in the modern business arena because new ideas for innovation in all forms – including new products, new processes, continuous improvement initiatives and so on – come from harnessing this human creativity. Creative ideas do not come from machines or ‘technology’.

There is already compelling evidence about the benefits of strategic human resource management, seeing people as part of the solution rather than as the problem for an organization. For example, in his research on companies in the USA, Pfeffer (1998) notes the strong correlation between pro-active people management practices and the subsequent performance of firms in a variety of sectors. It is strange, then, that human resources will often be the first target of cost reductions for firms. Such a ‘quick-fix’ approach will often rob an organization of one of its most important assets – human commitment and expertise. This is one of the tensions that operations managers have to face if they are excluded from corporate decisions: a corporate decision – for example, to downsize the workforce – can have a dramatic impact on operations capability, and often result in operations incapability.

Assets

Assets

These include fixed assets such as machinery and plant used in the transformation process, as well as liquid assets such as inventory. Both fixed and current assets are vitally important, and will either support the firm or cripple its capabilities in the market. As we shall see in Chapter 4, process technology is a key part of the firm's innovation capability. It enables the firm to provide a range of models and variations that modern business markets demand. Innovation is not restricted to the launch of new products (vitally important as this is); it also includes acquiring and managing new process technology. However, investment in new process or product technology is, by itself, not enough; an important part of the overall innovation process is in ensuring that there is sufficient and suitable human capacity – knowhow and learning – in place to accompany and complement the investment in new process technology. This is a key interface between technology management and operations management.

Costs

Costs

Managing costs is a key responsibility for operations managers. Whether operations managers are involved in price sensitive or premium price markets, it will fall to operations managers to create margins between costs and price. In his book Competitive Strategy, Porter (1980) suggested that organizations needed, ideally, to compete either on low cost or by providing differentiated products in order to be profitable and to avoid being ‘stuck in the middle’. However, this is now seen as overly simplistic, because an organization in the current era of market requirements may have to do both simultaneously. Even so, costs will always be an important responsibility for operations managers. In high volume production, where margins are usually very slim (for example, cars and PCs), costs and prices must be carefully controlled. The ability to do so does not necessarily mean a reduction in workforce numbers and other drastic measures. Instead, accumulated know-how and experience, appropriate use of technology and better process quality through continuous improvement will enable the organization to reduce costs.

A HISTORY OF OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT

A HISTORY OF OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT

Before we consider the topics that will be covered in this book, it is useful to understand how operations and the study of operations management have developed, and where they are today. Operations management has made many contributions to the development of modern management theory, beginning with scientific management and industrial engineering early in the twentieth century, through to the influence of Japanese management at the end of the century.

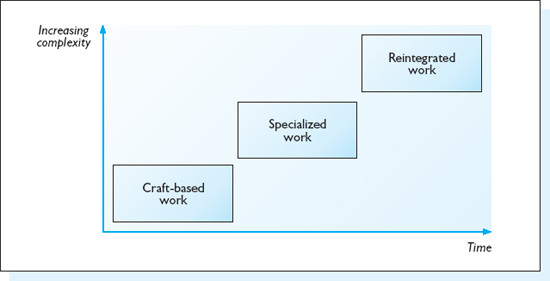

Over time, the set of operations practices used in organizations has become more complex. Figure 1.8 shows the three main types of operations practices that have evolved over time.

Operations, broadly defined, may be argued to have existed as long ago as the Pyramids and other great works projects, but the academic study of operations management only took off after World War II. However, many influential managers and scholars who shaped the modern practice of management have been associated with either the practice of operations or the study of operations management.

Figure 1.8 The evolution of operations practices.

On the other hand, as products or services and the organizations and processes required to produce them have changed, the way in which organizations and operations are organized has become larger and more complex. Most of the goods and services that we consume, as well as the goods and services used by the organizations that produce them, are routinely mass-produced.

Over time, operations have evolved from craft production, to mass production, to the systems in use today. In this section we will provide an overview of how the study of operations management has evolved, although over a much shorter time period.

Craft production to batch manufacturing

Craft production to batch manufacturing

The earliest way of organizing the production of goods and services was craft work. This is where individuals (or small firms) develop and deliver goods and services. Most industries originated as craft-based work, and many are alive today – particularly when customers demand individual products or services, such as bespoke tailoring.

However, the Industrial Revolution signalled the change in methods of working and the replacement or extension of human and animal power with machines. Activities that had formerly taken place in homes or workshops were transferred to factories, which often employed large numbers of people.

Although Adam Smith was an economist, his observations in The Wealth of Nations about the division of labour are now recognized as one of the foundations of operations management. Smith used the example of making pins, then an important industry, to show that by dividing the different activities required to make a pin between workers rather than each worker making an entire pin from start to finish, the operations would make significantly more pins.

A key development in the transition from craft production, with its low volumes and high costs per item, was the development of the American System of Manufactures (ASM). This can be defined as the sequential series of operations carried out on successive special purpose machines that produce interchangeable parts (quoted in Hounshell, 1984, p. 15). Many of the features of modern manufacturing are associated with ASM, including an organized factory structure, specialized machines, precision manufacture, interchangeable parts, co-ordinated work sequences and materials flows, and quality techniques.

Key historical figures in developing the ASM were Eli Whitney, Samuel Colt (firearms), Oliver Evans, Isaac Singer (sewing machines) and Cyrus McCormick (agricultural machinery). The main promoter of the idea of interchangeable parts was Eli Whitney, probably better known as the inventor of the cotton gin, who contracted to build a large volume of small arms with uniform parts made by machines rather than by hand, although he never really achieved either. On the other hand, the other entrepreneurs listed above made considerable progress during the last half of the 1800s towards developing truly interchangeable parts, even though the goal wasn't achieved until the remaining problems were resolved during the early twentieth century.

From batch production to mass production

From batch production to mass production

The transition away from craft production continued with the development of methods for analysing and improving the organization of work and the methods for getting work done: this became known as scientific management. ‘Taylorism’, as the system of the organization and management of production developed by F. W. Taylor became called, consisted mainly of setting rates for piecework and the practice of time study and the analysis of the elements of any task. He also proposed changes in the organization of supervision and management, as well as the workforce itself, including the development of planning departments for scheduling work.

The final ingredient in modern production systems was the development of the moving assembly lines at Ford in 1914, which created a new kind of production system. Ford had experimented widely in earlier automobile models with production techniques that had been developed for the new bicycle industry. Ford's system was highly effective for manufacturing a single product, in high volumes, on a continuous basis, to rigid standards. Producing in large batches, with tight inspection of products and machines (since workers weren't responsible for spotting errors), enabled Ford to use unskilled, often untrained workers, which compensated for the lack of skilled craftsmen. Ford's system for manufacturing the Model T at Highland Park (and later River Rouge) set the standard for production excellence until the 1930s, when the company abandoned its strategy of making only a single product and tried to produce varied products, for which the system was spectacularly unsuited. General Motors, under the leadership of Alfred Sloan, then took over the leadership of marketing and production in the automotive industry.

The term mass production itself came into popular use when the Encyclopaedia Britannica published an article about assembly line manufacturing at Ford. Henry Ford was the first person to see the potential for selling products cheaply to mass markets rather than to the wealthy: Peter Drucker has described this revolutionary strategy as achieving maximum profit by minimizing production costs whilst maximizing production volume. Between Ford's original Model T production system and the post-war mass production systems at Ford and many other manufacturers’, mass production became associated with a degenerated emphasis on throughput to achieve high volume and low cost, but with low quality and low flexibility. In fact, the pre-1930s Ford mass production system is very similar to the post-war Japanese just-in-time (JIT) production systems pioneered at Toyota (although the post-war Ford system can be considered to be the complete opposite of JIT, as we shall see in Chapter 7).

From the discussion above, you might fairly conclude that most of the development of modern production systems took place in the USA. The Americans did make their workshops and factories open to inspection by competitors, and many British and other European engineers and managers visited them and came away with new ideas about both machines and methods. On the other hand, adoption of American-inspired practices was often limited because they did not fit with the different evolution of European production systems, and the different managerial ideas guiding this evolution. (For example, British trade journals were publishing stories about Taylor early on.) However, the specific conditions that encouraged the development of the mass production ideology, based on mass markets, existed only in the USA and not elsewhere, so that it was mainly American machines and technology, rather than American management techniques that found a broader audience. Despite its name and origins in the USA, the key ideas of the AMS, for example, had been brought to wider attention by the mid-nineteenth century, especially in Britain through the display of American products at the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851.

Beyond mass production

Beyond mass production

During the 1980s the economy of Japan expanded enormously, predominantly due to the competitive advantage that was being achieved by its automobile and electronics firms. It became clear that there were some fundamentally different methods being used by these firms in the design and production of their goods. Quality differences were noted – Japanese cars had gained a reputation for their quality and reliability in particular, but when this was measured objectively they contained less than one-hundredth of the defects of their western counterparts. In addition, productivity differences of 2 : 1 were found (Womack et al., 1990) – the Japanese plants were twice as productive as their competitors. The quality difference was noted to be associated with an approach that became known as Total Quality Management (see Chapter 9). The firms were noted to hold very little stock and parts were delivered as they needed them – just-in-time (JIT – see Chapter 7). Overall, these firms were noted to be Lean or World Class (see Chapters 2 and 11).

Part of the reason for these differences in performance was through a fundamentally different approach to organizing work. The mass production era promoted specialism, with firms being organized into a functional structure. This worked well for many years, but eventually each function began to concentrate on its own needs to grow and perform. An example of this is the marketing department of a leading brand of soft drinks, who decided to increase sales by announcing a cut-price promotion (12 cans for the price of 8) during a summer heat wave even though the bottling plant was already running 24 hours per day, 7 days per week to keep up with demand. When the promotion increased demand for soft drinks, the existing stocks were exhausted and revenues actually fell since the drinks being sold were being retailed for much less. The blame for lost revenues fell on operations, not marketing.

The focus on specialism neglected a key issue: customers do not buy products from functions, they buy the output of processes. Processes are typically cross-functional, rather than being based in a single function (Figure 1.9). For example, product quality depends not only on shop-floor workers, but also on the work of designers, purchasing, distribution and marketing. To meet customer expectations, different functions must be reintegrated around processes that create and deliver products that customers want to buy. Furthermore, with increasing proportions of the value of products and services being bought-in (or outsourced) rather than made in-house, the imperative to integrate suppliers into the process has become even stronger. Customers are also a part of this process, and much work has been carried out in operations management to enhance the means by which customers are integrated.

Figure 1.9 Functions and process.

CURRENT ISSUES IN OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT

CURRENT ISSUES IN OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT

Some of the issues that operations managers must face include new pressures on operations management, the different operations management challenges of different types of organizations, and new imperatives for operations performance.

The new scope of operations management

The new scope of operations management

Operations management has developed beyond its roots in the study of manufacturing, also known as factory management or production management. Although operations management is still concerned with manufacturing operations, organizations as varied as hospitals, overnight package delivery services and charities are all concerned with operations. Operations management is increasingly important in not-for-profit organizations such as government departments and agencies, and other organizations that provide services such as charities and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Instead of producing goods and services to make a profit, not-for-profits must use limited resources wisely – for example, through trying to provide services to as many people as possible, or as high a level of service as possible to a fixed customer base, at a given level of resources.

Operations as an open system

Operations as an open system

Despite the differences between manufacturing, service and not-for-profit organizations, all of these can be viewed as systems for acquiring inputs from the environment, transforming them, and exporting outputs to the environment.

The modern view of operations management treats operations as an open system, rather than a closed system. The old closed-system view treated operations as independent of its environment, suggesting that, in a stable and predictable environment, management's task was to design the optimum system to fit that environment and then to run things efficiently. This is very much the attitude of scientific management, operations research and industrial engineering. It was appropriate for the less competitive business environment of the past; it is wholly inappropriate for the modern business era.

By contrast, the open-system view of operations takes into account the need for operations to interact with the environment, including acquiring the resources that it consumes and exporting resources to the environment. As the environment is continuously changing, operations must change and adapt to environmental change, and thus the design of a static, unchanging operations function is not feasible.

During the 1990s, operations management became concerned with managing operations across organizational boundaries as well as within them. As the limits to improvement within particular plants or divisions began to be reached, operations had to look for new ways to create efficiencies. Instead of looking within the organizational boundaries the focus became external, with concentration on the management of supply into and through the organization. The ideas put forward in the early 1990s were concerned with creating efficiency both into and through the organization. The various terms for concepts, including World Class Manufacturing, Lean Manufacturing and Agile Production, all focused on one key issue; the alignment of internal and external process – the management of the supply chain.

Supply chain management is not only concerned with the purchasing of goods and materials but also with the development of strategies to manage the entire supply process – i.e. not just inputs but also throughputs. This strategic focus has led to the development of strategies such as Outsourcing, Partnership Sourcing and Supply Base Rationalization and Delegation strategies. All of these strategies have been designed to align with internal strategic initiatives such as just-intime (JIT) and Total Quality Management (TQM) – i.e. working closer with fewer suppliers to add more value to the business.

The value adding principles of strategically focused supply strategies are well documented. If managed effectively these strategies can enhance value by improving time-to-market, sharing technologies to create new innovations, sharing risks to allow enhanced development of ideas, sharing costs and sharing benefits. In addition, the imposition of outsourcing strategies and supplier tiers can make the customer more flexible to global competition, as it can concentrate on its core competencies such as design without being bogged down with having to manage the assembly parts of the process. Furthermore, by working together suppliers and customers can identify cost drivers and find ways to reduce these jointly, instead of focusing purely on price. This cost transparency approach can yield significant benefits for both the customer and the supplier organization.

Strategic purchasing and supply covers the whole of operations. Purchasing acquires and manages the inputs – raw materials, sub-assemblies, and services – that the organization uses to create and deliver its outputs of goods and services. These goods and services have to be purchased from approved supply sources, and conform to required levels of quality and delivery schedules. Supply manages resources that are held within the organization, and which are moved outside, and is concerned not only with the inputs but also with the transformation and management of goods and services through the organization.

New pressures on operations management

New pressures on operations management

There are four new pressures on operations management:

1 Globalization. Organizations compete in international markets, and face competition from international competitors in their own home markets.

2 Employees. Operations managers are increasingly responsible for motivating and empowering employees. One reason is that organizations depend increasingly on the flow of ideas for improvement from staff.

3 Ethics. Many of the ethical dilemmas facing organizations are directly related to operations, and this will be discussed further in Chapter 11. For example, Shell's decision in 1996 to dump the Brent Spar oil platform at sea once it had no further use for it sparked Europe-wide boycotts of Shell products. Other organizations have been ‘named and shamed’ because they or their subcontractors have employed under-age (‘child’) labourers. Operations may also be directly or indirectly involved with other ethical issues such as animal testing of products, or supply chain issues.

4 Environment. Operations directly or indirectly account for the majority of the environmental impacts of organizations. The processes by which products are created result in waste products and emissions. Goods and services also affect the environment – for example, McDonald's has switched from styrofoam packaging for its fast-food sandwiches to paper containers, substantially reducing the amount of non-recyclable waste generated by its stores.

New imperatives

New imperatives

There are major imperatives for operations managers, including:

![]() Performance objectives: as you will see throughout this book, the performance challenges for operations have changed over time. During the 1950s, operations performance was primarily judged by cost. During the 1980s, quality was added to cost, particularly in manufactured products where markets were under increasing pressure from Japanese products. Expectations of continuous improvements to product and service quality increased dramatically. Today, many industries have added the need to innovate new products and services as well as to deliver products and services faster, more reliably and to individual customer requirements.

Performance objectives: as you will see throughout this book, the performance challenges for operations have changed over time. During the 1950s, operations performance was primarily judged by cost. During the 1980s, quality was added to cost, particularly in manufactured products where markets were under increasing pressure from Japanese products. Expectations of continuous improvements to product and service quality increased dramatically. Today, many industries have added the need to innovate new products and services as well as to deliver products and services faster, more reliably and to individual customer requirements.

![]() Utilizing communications and computers: the use of computers and communications technologies has affected operations on a par with (if not more than) other areas of the organization. Organizations use personal computers, servers and networks to link different activities internally, allowing work to be performed wherever it makes sense, and making it possible to bring operations closer to customers.

Utilizing communications and computers: the use of computers and communications technologies has affected operations on a par with (if not more than) other areas of the organization. Organizations use personal computers, servers and networks to link different activities internally, allowing work to be performed wherever it makes sense, and making it possible to bring operations closer to customers.

Challenges for service operations management

Challenges for service operations management

Like manufacturing, the service sector is undergoing rapid change. First, as in most management activities, global competition and technological change are creating pressures that affect industries, firms and individuals. Many previously unpaid activities – for example, personal services such as housecleaning or childcare – are now being performed outside the household for pay, and are formally measured as economic activities. Along with this growth in the service sector, techniques learned from manufacturing are being applied to new and existing services to increase productivity.

Along with changes in service businesses, there have been many changes to not-for-profit services, including the government and voluntary sectors. In most countries the not-for-profit sector provides a variety of services to individuals, businesses and other parts of the public sector. This provision is shifting to the private sector or being eliminated in many countries, which has a major effect on budgets and taxes.

Organizations themselves are using services as a source of competitive advantage, to differentiate their products or to increase revenues. When physical goods are identical or offer similar benefits, they can then be differentiated through the type or quality of services associated with them. For example, there may be little difference between personal computers offered by different vendors, but after-sales support services such as customer support hotlines can create differences in customer experiences. Another example is Dell Computer's Internet marketing site: customers or potential customers can configure their own personal computer to their exact specification, and be given prices and delivery dates, all based on sophisticated information technology. Why bother going to a store or dealing with sales personnel if you know what you want?

The service content of products is also increasing. For example, purchasers of the Ford Model T were expected to perform maintenance and repair activities themselves; purchasers of the Toyota Lexus have their automobile picked up from their homes, not only maintained and repaired but also valeted, and then returned to their homes. They also automatically become members of the Lexus Club, which includes many benefits not directly associated with car ownership, such as discounts on travel, gifts, wine and theatre tickets. Along with this, many customers now expect complete service solutions from providers. Package holiday providers arrange not only transportation, but also lodging, entertainment, food and excursions for their clients. As well as selling ingredients and packaged dishes, supermarkets such as Waitrose and Sainsbury are now providing gourmet meals created (if not prepared) by celebrity chefs, so that customers can vicariously dine in top restaurants in their own dining rooms.

Challenges for manufacturing operations

Challenges for manufacturing operations

A major development since the 1970s has been the increase in growth within the service sector, often at the expense of the manufacturing base in many Western countries. Not surprisingly, the number of manufacturing jobs has declined in many countries in the West. For example, in the USA manufacturing jobs accounted for 33 per cent of all workers in the 1950s; this fell to 30 per cent in the 1960s, 20 per cent in the 1980s, and by 1995 the figure was lower than 17 per cent. The implications of this decline are explored by a number of writers. One of the most powerful discussions is in the book America: What Went Wrong? (Bartlett and Steele, 1992).

The problem is that the manufacturing element has often been ignored or downplayed in the total provision of goods and services. Indeed, there has often been a view of the manufacturing element as a secondary consideration within the total provision of goods and services, as Garvin (1992, p. xiv) describes:

All too often, top managers regard manufacturing as a necessary evil. In their eyes, it adds little to a company's competitive advantage. Manufacturing, after all, merely ‘makes stuff’; its primary role is the transformation of parts and materials into finished products. To do so it follows the dictates of other departments.

Brown (1996) suggests that the key reasons behind the relegation of manufacturing include:

![]() Downgrading the importance of manufacturing at societal/government levels

Downgrading the importance of manufacturing at societal/government levels

![]() Failing to educate school students sufficiently in technical/commercial areas

Failing to educate school students sufficiently in technical/commercial areas

![]() Business schools teaching ‘quick-fix’ management tools, rather than providing a strategic framework

Business schools teaching ‘quick-fix’ management tools, rather than providing a strategic framework

![]() Failing, both at national and company level, to invest in appropriate management development and training

Failing, both at national and company level, to invest in appropriate management development and training

![]() Failing at company level to view manufacturing in terms of strategic importance

Failing at company level to view manufacturing in terms of strategic importance

![]() Having a view of the business which is governed essentially by short-term financial criteria.

Having a view of the business which is governed essentially by short-term financial criteria.

Garvin (1992, p. xiv) argues that the definition of manufacturing operations has to be seen in a wider context than might often have been assumed in the past, and he quotes the Manufacturing Studies Board publication Toward a New Era in US Manufacturing, in which it is stated:

Part of the problem of US manufacturing is that a common definition of it has been too narrow. Manufacturing is not limited to the material transformation performed in the factory. It is a system encompassing design, engineering, purchasing, quality control, marketing, and customer service as well.

We need only to look at the contribution of manufacturing to both the Fortune 500 (firms in the USA) and the Fortune Global 500 in order to confirm how vital manufacturing can be. We should bear in mind that it is not only those firms that we might automatically associate with being a ‘manufacturing company’ which are important. The giant retail outlets within the Fortune 500 are also very dependent upon manufactured goods – this may seem obvious, but often people will classify retail as a service industry, as if, somehow, it is a sector that is entirely independent from manufacturing. The fact is, retail is very dependent upon the manufacturing base.

There are two important issues here. The first is that manufacturing and service firms often link together and are dependent upon each other in order to complete the transfer from inputs to outputs of goods and services to customers. The second issue is that services firms have not replaced manufacturing organizations when it comes to balance of payments and exports. Service exports have not managed to plug the gap between manufactured imports and exports in many countries. Operations management practices therefore also impact not only on corporate success, but also on the economic success of nations.

THE PLAN OF THIS BOOK

THE PLAN OF THIS BOOK

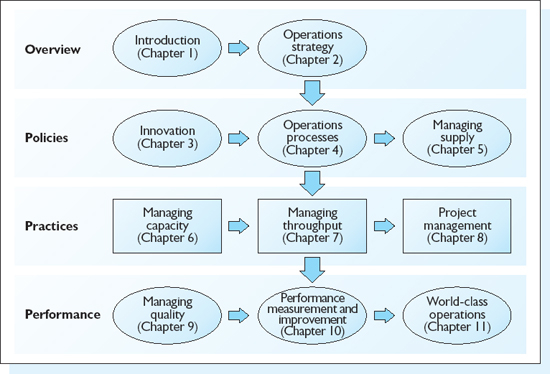

The topics within operations management are inter-related. The design of this book presents the chapters so that the major ideas are unfolded in a logical sequence, around the policies, practices, and performance objectives of the organization. Figure 1.10 shows this sequence.

Following the overview, the first part introduces the basic elements of operations policies.

This discussion provides the groundwork for the second part, which is about the practices that organizations put into place to realize these policies.

The third part looks at the performance side of operations. It concludes with some ideas about managing operations for sustainable competitive advantage, and future directions that operations is taking.

Figure 1.10 Plan of the book.

Finally, the supplementary chapters give an insight into some basic numerical techniques that can be used to help solve simple problems that we often encounter within firms.

Plan of each chapter

Plan of each chapter

Each chapter begins with a short case or vignette taken from real-life operations. The theory and models that are relevant to the chapter topic are introduced next. Each chapter ends with a summary of key points, a case study, key questions and a list of key terms and concepts.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

Operations management is important because when an operation works well, goods and services are delivered to customers when they want them, with something extra that delights the customer and creates customer loyalty. The challenge for operations managers is to make this happen. If an organization has outstanding financials, human resources and market plans, and utilizes the very latest IT system but can't deliver products and services, then it will not succeed. Operations management makes this happen.

The study of operations management shows us how to accomplish and improve the operations task of the organization. Operations is changing as fast as organizations themselves change – everyday, products and processes are being improved.

Operations management contributes to organizational success or failure. Every organization has an operations function, which is what the company does. Within an organization, operations produces the organization's goods and services for internal and organizational customers or clients.

Operations management focuses on the processes by which work gets done. Processes bring together the four ‘P's of operations – policies, processes, practices and performance. These processes have evolved over time from craft-based work to mass production and other specialized work, and today's reintegrated work. Processes also tie operations to the other functional areas of the organization, and to suppliers and customers. Processes can be categorized using the volume–variety matrix and other characteristics.

Operations managers are responsible for managing human resources, assets and costs. Operations managers must also consider a range of imperatives, including ethical and environmental considerations, and new technologies such as the Internet.

The operations process itself can be described using the transformation model, which applies to both services and manufacturing. In the wider perspective, operations managers bring together resources, knowledge and market opportunities, as shown in the dynamic convergence model.

Case study

Toyota: archetypal operational excellence

At the beginning of this chapter we asked the question, ‘Who comes to mind when you think of successful organizations?’ There's no doubt that when we speak about excellence in operations within the motor industry, Toyota comes to mind. This is because Toyota has constantly aimed to improve all areas of operations. For example, in the 1970s people were attracted to Toyota cars for many reasons, but the main one was usually that they were excellent value for money. During the 1980s, Toyota acquired a reputation for building cars that were very reliable, as well as providing many of the features that other manufacturers would include as optional extras as standard. During the 1990s, they were seen in the car market to have retained their value and quality (never outside the top 10 in the JD Power survey of reliability in the UK). However, they had also become highly innovative, developing new models in around half the time of their competitors in the western automotive sector. Their marketing slogan in the UK and elsewhere: ‘The car in front is a Toyota’.

It is not through clever marketing that Toyota's success (consistent growth and profitability) has been achieved; rather, outstanding operational capability has been at the root of their success, through the application of the principles of the Toyota Production System (TPS). These were set out by Eiji Toyoda and Taiichi Ohno after World War II and were fully operational by the 1960s. Many of the principles, such as the elimination of waste, were a matter of expediency rather than any great invention at the time. Japan had very few natural resources, limited space and, at the time, little foreign currency to buy machinery. Other principles are the use of the innovation potential of every one of their employees and the close relationships (often involving cross-holdings of shares) with suppliers.

By the early 1990s, the name ‘Toyota’ had become synonymous with excellence in operations management. Studies have repeatedly used Toyota as the benchmark against which performance is judged, consistently showing quality performance significantly better (less than one-hundredth of the defects of other car producers in one study) and productivity higher than competitors (2 : 1 differences are not unusual). The importance of the TPS is highlighted by its imitators, not just in corporate Japan but around the world. No self-respecting automotive company or supplier today is without its version of the TPS. Yet none have been truly able to imitate the system, because while these competitors are imitating one version, continuous improvement means that Toyota are on to the next.

In 2000, Toyota announced plans to expand their capacity by 2 million vehicles a year, in an already saturated global market. This will put significant cost pressure on their competitors, and the consolidation evident in the rest of the automotive industry is likely to continue. It also highlights the firm's grip on the competitive characteristics of the market in which they operate.

1 Describe how the input/output/feedback model can be used in each of the following:

a. A university

b. A hospital

c. A car plant.

2 List five firms, and then examine how they line up within Chase's manufacturing/service continuum.

3 List three household products and describe how elements of both manufacturing and service have played a part in the purchase of these items.

4 List six examples of both craft and mass production.

Key terms

Craft production

Closed system

Mass production

Open system

Operations

Operations management

Operations managers

Scientific management

References

Bartlett, D. and Steele, J. (1992). America: What Went Wrong? Andrews and McMeel.

Brown, S. (1996). Strategic Manufacturing for Competitive Advantage. Prentice Hall.

Chase, R.B. and Tansik, D. A. (1983). The customer contact model for organisation design. Man. Sci., 29(9), 1037–50.

Galloway, L. (1998). Principles of Operations Management, 2nd edn. Thompson.

Garvin, D. (1992). Operations Strategy, Text and Cases. Prentice Hall.

Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C. (1994). Competing For The Future. Harvard Business School Press.

Hounshell, D. (1984). From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Normann, R. (1991). Service Management. John Wiley.

Pfeffer, J. (1998). The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First. Harvard Business School Press.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy. Free Press.

Ridderstrale, J. and Nordstrom, K. (2000) Funky Business: Talent Makes Capital Dance. FT Books.

Russell, R. S. and Taylor, C. W. (2000). Operations Management. Allyn and Bacon.

Schroeder, R. (1999). Operations Management, 6th edn. McGraw-Hill.

Smith, A. (1986). The Wealth of Nations. Penguin Books (first published 1776).

Voss, C. A., Ahlstrom, P. and Blackman, K. (1997). Benchmarking and operational performance: some empirical results. Int. J. Operations Man., 17(9/10), 1046–58.

Whitston, K. (1997). The reception of scientific management by British engineers, 1890–1914. Business History Rev., 71, 207–29.

Wilson, J. M. (1995). An historical perspective on operations management. Production Inventory Man. J., 61–6.

Wilson, J. M. (1996). Henry Ford: a just-in-time pioneer. Production Inventory Man. J., 26–31.

Wilson, J. M. (1998). A comparison of the ‘American system of manufactures’ circa 1850 with just-in-time methods. J. Operations Man., 16, 77–90.

Womack, J., Jones, D. and Roos, D. (1990). The Machine That Changed the World. Rawson Associates.

Zeithaml, V. and Bitner, M. J. (2000). Services Marketing, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill.