CHAPTER

Operations strategy: the strategic role of operations

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Case study

Peters and Waterman's popular management book In Search of Excellence (1982) portrayed IBM as not only meeting but also surpassing all eight of their attributes of excellent companies. As Peters admitted in 1990, ‘We seemed to suggest that all 400 000 IBM-ers could be seen walking on water!’ In retrospect, the IBM that lost one-third of its PC market share to Apple Computers and the Compaq Corporation (neither of which had featured in the book) seemed not to be quite so excellent.

What happened to IBM between 1982 and 1990? Like many other firms, it lost ground to more aggressive competitors. IBM's traditional market segment was large corporations: Apple and Compaq outperformed IBM in home computing, small business computing and education.

Similarly, in the UK motorcycle industry, Honda and other Japanese manufacturers first attacked Triumph Motorcycles, the traditional market leader, in the low-end 50 cc and 125 cc model ranges. Over time they gradually introduced more powerful models, gradually eroding Triumph's market share where it was strongest.

In the USA General Motors’ domestic market share declined from 60 per cent in 1979 to 30 per cent in 2000, when other firms more aggressively developed market segments such as minivans, sports-utility vehicles, four-wheel drives and turbos.

A common theme of these examples is that market leaders are vulnerable to attack in non-core segments, where they are often not paying attention. Once new entrants have established a peripheral market position, they can attack the leader in its core businesses. This relies on using operations as a strategic weapon, because capabilities have to be put in place. However, once particular capabilities are in place – for example, fast innovation, quality, and low cost production – they can then be utilized to gain a powerful advantage for an organization.

Aims and objectives

Aims and objectives

This chapter explores strategy, and in particular its relevance to operations and operations management. Strategy and operations strategy are first defined, and then the developments of operations strategy are explored.

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

![]() Define the strategic role of operations and operations managers

Define the strategic role of operations and operations managers

![]() Appreciate the importance of strategy to operations and operations management

Appreciate the importance of strategy to operations and operations management

![]() Describe the major types of strategies and strategy processes

Describe the major types of strategies and strategy processes

![]() Explain the key developments in operations strategy in both service and manufacturing contexts.

Explain the key developments in operations strategy in both service and manufacturing contexts.

WHAT IS STRATEGY?

WHAT IS STRATEGY?

Operations capabilities are at the heart of the success of companies such as Dell, Nokia and Sony, mentioned in Chapter 1. Although other areas such as marketing and human resource (HR) management are also important, even with the best marketing or HR plans in the world, without operations capabilities an organization will flounder because it cannot deliver on its promises to customers.

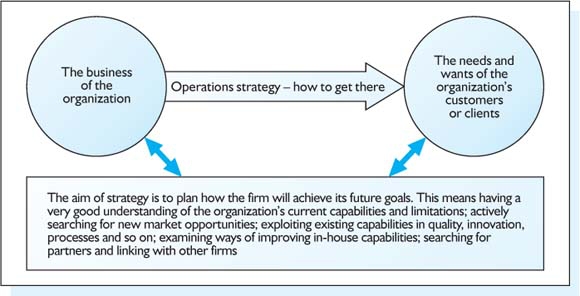

Organizations can no longer compete on a single dimension such as low cost, high quality, or delivery, but must provide all of these (and more!) simultaneously. Operations managers must put in place a strategy to develop and maintain the operations capabilities to support these competitive objectives, which traditional approaches to strategy do not do. In essence, strategy is about the ‘how’ of an organization's aims – how it will go from its current state to its intended future position, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 The basic aim of strategy.

The origins of strategy

The origins of strategy

The concept of strategy originated in military terminology, where strategy refers to plans devised to outmanoeuvre the opposition. In business, firms attack where and when other firms are vulnerable.

In the earth-moving industry, Komatsu attacked Caterpillar initially in market segments that Caterpillar considered unimportant. Komatsu used a typical Japanese tactic, miniaturization (much used by Sony). Komatsu's smaller earth-moving machines were more nimble on site than Caterpillar's larger, more cumbersome ones. Komatsu also introduced models that could go underwater, another of Caterpillar's weak areas. Komatsu's stated intent was to ‘Surround and then kill the cat!’

Caterpillar, however, was motivated by Komatsu's attack to defend itself. The company developed and implemented a strategy that allowed its plants to compete on a range of strategic operations capabilities simultaneously. By 2000, Caterpillar's market share in Japan was higher than Komatsu's share in the USA.

New strategies often result from competitive threats. The new strategy must be made clear and be understood by employees, and must be supported by operations capabilities in order to work. At Honda, for example (Whittington, 1993, pp. 69–70):

[When] Honda was overtaken by Yamaha as Japan's number one motorbike manufacturer, the company responded by declaring ‘Yamaha so tsubu su!’ (We will crush, squash and slaughter Yamaha!). There followed a stream of no less than eighty-one new products in eighteen months. The massive effort nearly bankrupted the company, but in the end left Honda as top dog once more.

Honda's strategic operations capabilities allowed it to launch a range and volume of new products within a short time. Otherwise, it would have been arrogant and pointless to think that the company would overtake Yamaha.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple Computers, he also used strategy as an offensive weapon (Financial Times, 12 November 1997):

Mr Jobs . . . declared ‘war’ on Dell Computers, one of Apple's most successful competitors. ‘We are coming after you, buddy’, Mr Jobs declared as he displayed a huge image of Michael Dell, Dell founder and chief executive, with a target superimposed on his face. Mr Dell became the target of Apple's ire, Mr Jobs said, because he had refused to retract a statement that Apple should be dissolved. ‘I'd shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders’, Mr Dell said.

Again, Apple had to put in place a clear operations strategy to go after Dell, and by 1999 Apple had vastly improved its operations capabilities.

Strategy formulation

Strategy formulation

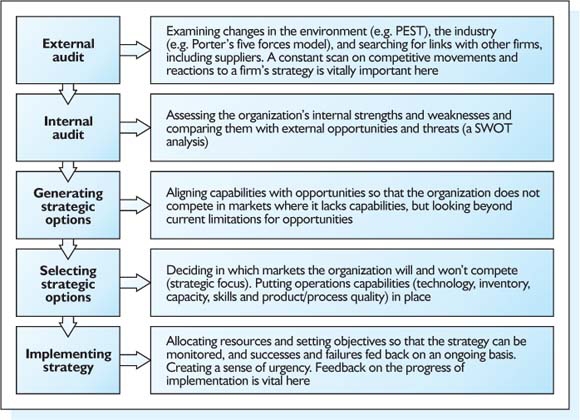

There is, not surprisingly, no single best way of developing a strategy. The major elements of the strategic planning process are indicated in Table 2.1.

Every organization must plan and implement strategy to fit with its vision and mission. Important elements that need to be in place, both internal and external, are illustrated in Figure 2.2.

The traditional approach to formulating strategy simply seeks to match the firm's existing capabilities with a particular market segment that best exploits this capability. This focuses on the ‘strategic fit’ between resources (particular operations capability) and attractive markets.

Table 2.1 Factors in strategic decision-making (adapted from Johnson and Scholes, 1999)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Another approach is to be more ‘visionary’ in formulating strategy, perhaps through devising future scenarios that go beyond matching resources to ‘strategic stretch’. For example, alliances can be formed with other firms.

Although strategy is complex, it is essentially about three goals. First, strategy is about satisfying (and, in some cases, delighting) customers. Here, the strategist searches for market requirements. Second, strategy is about making the best use of resources, either alone or with partners. Partners may initially be seen as competitors, but alliances help diminish threats from other competitors. Third, strategy is about developing superior capabilities, which competitors either cannot (or find it extremely difficult to) copy. For a firm to thrive, it must be able to manage these three strategic dimensions simultaneously.

Figure 2.2 An example of the strategy planning process.

The best firms learn, adopt and utilize world-class operations capabilities through seeking out and accumulating capabilities. Otherwise, there is a gap between strategic intent and strategic capability.

The strategy planning process answers the following key questions:

![]() What business is the firm really in?

What business is the firm really in?

![]() What does it do best?

What does it do best?

![]() Should it outsource any current activities, and if so why, where and how?

Should it outsource any current activities, and if so why, where and how?

![]() How can opportunities be exploited quickly and how can threats be warded off?

How can opportunities be exploited quickly and how can threats be warded off?

Strategy therefore relies on continuously gathering information to support analysis, choice and implementation. Feedback helps position the firm where it is most competitive. Strategy also creates an appreciation of the capabilities and limitations of the firm's resources, together with its responsibility to stakeholders.

Who is involved?

Who is involved?

Everyone in the organization is ultimately affected by strategy. Who should be involved in forming strategy in the first place? Both the top-down approach to strategic planning and the bottom-up approach have been advocated, and many organizations combine the two. It is easier to suggest a particular strategy, however, then actually to realize it. To achieve a particular business goal, strategies have to be in place throughout the entire organization.

One of the writers of this book (Brown, 2000) is highly critical of top-down approaches:

Strategy is seen by some as something which is devised at the highest levels of the firm – where . . . in some firms there may not be any senior-level manufacturing, or operations management presence – and then simply ‘passed down’ through levels of hierarchy – with all the filters and blockages to accomplishing the strategy that this may bring. Pick up any textbook of strategy and the same old models seem to appear time after time. The model goes like this. Strategy starts at the top (the corporate level); it then passes DOWN to business levels (where business strategy is devised) and then passes DOWN again to functional levels, including operations. Some publications say that there should, ideally, be dialogue in the process – particularly where a resource-driven (not necessarily including operations capabilities, by the way) strategy is being pursued. However, in the main, the top-down model of strategy remains the dominant model – you will see it articulated, especially, when a new CEO is put in place. All eyes will be on how the person at the top of the hierarchy will create a strategy. But the model is fatally flawed. It is flawed because of a number of reasons including:

![]() It enforces the idea of different realms of strategy – each with its own agenda – within the three levels of the firm.

It enforces the idea of different realms of strategy – each with its own agenda – within the three levels of the firm.

![]() It assumes that corporate decisions will, somehow, line up with business and functional strategies to make some sort of perfect fit between them.

It assumes that corporate decisions will, somehow, line up with business and functional strategies to make some sort of perfect fit between them.

![]() It also assumes that corporate managers actually know something about operations capabilities and are able to leverage these capabilities as part of the strategic plan. However . . . such an assumption is, often, totally without any foundation whatsoever.

It also assumes that corporate managers actually know something about operations capabilities and are able to leverage these capabilities as part of the strategic plan. However . . . such an assumption is, often, totally without any foundation whatsoever.

![]() It encourages a hierarchical, top-down approach where, as a result, there may be little or no ownership of the planning process and the subsequent strategic plan.

It encourages a hierarchical, top-down approach where, as a result, there may be little or no ownership of the planning process and the subsequent strategic plan.

In top-down strategic planning, a very few people make decisions that affect many people. If the top-down approach is used, excellent communication processes also need to be in place so that all employees ‘own’ the change. Strategic management writers often endorse the top-down view, resulting in a false division between ‘corporate’ and ‘operations strategies. The outcome is described by Brown (1996):

1 Corporate strategy books tend to ignore the strategic importance and contribution of operations in corporate decisions.

2 Operations books – with rare exceptions – also ignore the strategic importance of operations in corporate decisions, and concentrate on tools and techniques of day-to-day operations management.

As you can see, business and operations strategies need to be closely aligned for organizations to thrive in the modern competitive era.

Market-led versus resource-based strategies

Market-led versus resource-based strategies

Strategy is sometimes seen as an either/or scenario. The firm can either compete on its capabilities – a resource-based strategy – or pursue a market-driven strategy. There has been considerable debate on the conflict between the two strategies. The latter can be seen as an ‘outside-in’ approach (market-driven); the former can be viewed as an ‘inside-out’ approach (resource-driven). Each approach has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

The ‘outside-in’, market-based strategies were popularized by Michael Porter in Competitive Strategy (1980) and Competitive Advantage (1985). Perhaps not surprisingly, its main advocates today are those who concentrate on marketing strategy.

The market-based view of strategy proposes that the firm should seek external opportunities in new and existing markets, or market niches, and then aligns the firm with these opportunities. This requires evaluating which markets are attractive and which markets the firm should exit.

A market-led strategy does not ignore a firm's capabilities. Indeed, a market-led strategy demands that a coherent, unifying and integrative framework needs to be in place if the transition from market requirements to in-house capabilities is to be realized. However, this is done only when particular market opportunities have been deemed to be ‘attractive’ for the firm. The danger with market-led strategies is that the firm may end up competing in markets in which it may not have sufficient capabilities to do so effectively. Thus there will be a strategic gap between what the firm would like to do (and may have chosen to do) and what it can actually do!

In contrast to the market-led approach to strategy are the resource-based strategies. The strategic importance of resources, both tangible and intangible, is not a new idea. For example, Penrose (1959) argued that firms were collections of productive resources that provide firms with their uniqueness and, by implication, their means of competitive advantage. The role of internal resource-based strategies gained prominence again in the early 1990s with the emphasis on ‘core competencies’, which argued that the chief means of sustaining competitive advantage for a firm comes from developing and guarding core capabilities and competencies.

A successful resource-based strategy process requires that strategists need to be fully aware of, and make the best possible use of, the firm's capabilities. This may seem obvious but, as we shall see in the next section, those who make strategic decisions may not understand the capabilities that reside within their plants’ operations. In essence, these capabilities can provide strategic advantage only if the firm succeed in both outperforming competitors and satisfying customers. The dangers of adopting a resource-based strategy are summarized by Verdin and Williamson (1994, p.10):

Basing strategy on existing resources, looking inwards, risks building a company that achieves excellence in providing products and services that nobody wants . . . market-based strategy, with stretching visions and missions, can reinforce and complement competence or capability-based competition. And that successful strategy comes from matching competences to the market.

THE STRATEGIC ROLE OF OPERATIONS AND OPERATIONS MANAGERS

THE STRATEGIC ROLE OF OPERATIONS AND OPERATIONS MANAGERS

Operations managers are responsible for managing human resources, assets and costs, as shown in Chapter 1. Operations managers also ensure that the organization can compete effectively. Strategy is important because it maps how the organization will compete. For example, in 1991 Hewlett Packard announced that it would compete in the PC market as well as producing printers. To do so it would concentrate on assembly, not manufacture. This required Hewlett Packard to form, develop and nurture strategic relationships with suppliers, rather than manufacturing everything in-house. Hewlett Packard's business was focused as a result.

The elements of strategy

The elements of strategy

The day-to-day tasks that operations managers are responsible for (described in Chapter 1) have strategic consequences, because they are necessary to how operations supports the firm in its chosen markets. Brown et al. (2000, p. 57) identified a list of strategic imperatives:

![]() Process choice – selecting the right approach to producing goods or delivering services

Process choice – selecting the right approach to producing goods or delivering services

![]() Innovation – adapting or renewing the organization's processes or outputs to adapt to changes in the external environment

Innovation – adapting or renewing the organization's processes or outputs to adapt to changes in the external environment

![]() Supply chain management – managing external relationships with suppliers so that inputs are supplied effectively and efficiently

Supply chain management – managing external relationships with suppliers so that inputs are supplied effectively and efficiently

![]() Resource control – managing inventories

Resource control – managing inventories

![]() Production control – managing processes effectively and efficiently

Production control – managing processes effectively and efficiently

![]() Work organization – managing and organizing the operations workforce

Work organization – managing and organizing the operations workforce

![]() Customer satisfaction – managing quality.

Customer satisfaction – managing quality.

Mismanaging any of these strategic imperatives will jeopardize the organization's future.

An operations strategy must include at least the following:

![]() The capacity required by the organization

The capacity required by the organization

![]() The range and location of facilities

The range and location of facilities

![]() The investment in product and process technology

The investment in product and process technology

![]() The formation of strategic buyer–supplier relationships

The formation of strategic buyer–supplier relationships

![]() The introduction of new products or services

The introduction of new products or services

![]() The organizational structure of operations.

The organizational structure of operations.

STRATEGY IN CONTEXT: MANUFACTURING AND SERVICE STRATEGIES

STRATEGY IN CONTEXT: MANUFACTURING AND SERVICE STRATEGIES

Manufacturing strategy

Manufacturing strategy

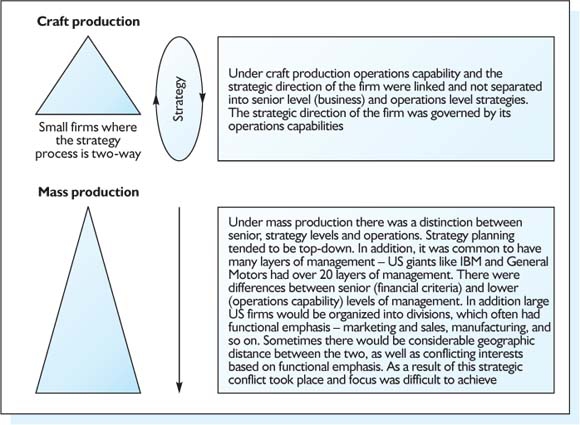

In Chapter 1 we described the change in manufacturing from craft to mass production. This transition also deeply affected how organizations developed strategies. Four strategic factors emerged.

First, in craft production manufacturing processes and the business of the firm were inextricably linked, but under mass production operations became a functional area. As enterprises grew in size and became functionally organized, operations managers lost their presence in the most senior levels of the firm despite the contribution of operations to the firm's capabilities (highlighted in the resource-based approach).

Second, the role of operations managers often became that of technical specialist, as opposed to an involvement in the strategic business of the firm. Thus operations’ contribution was often ignored until strategic plans had already been formulated by an elite planning group whose understanding of the specifics of manufacturing or assembly was very limited.

Third, strategy formulation and planning became the prerogative of senior managers and, as we have noted, operations personnel were, typically, excluded from the process. Thus, operations strategies – if they existed at all! – were merely the means by which an already existing business strategy became translated into plant operations. As we shall see later in the chapter, this may have been appropriate for the relatively ‘static’ market conditions in mass production, but market requirements are now entirely different.

Fourth, there was a mismatch in the synchronization of timing between business strategy and – where it existed at all – operations strategy within firms. Timing remains a key ingredient in strategic planning, particularly in creating a sense of urgency for strategic implementation.

These four changes were, perhaps, inevitable due to the growth of large, multi-divisional enterprises within the USA. Increased size led to increased levels of hierarchy within the firm. Excluding operations personnel from the strategic direction of the firm thus created tensions between conflicting goals within the firm.

As a result, strategy and operations criteria began to diverge. Senior level strategists were now often driven by short-term financial criteria. Consequently, a trend developed of measuring the wrong things in operations. For example, a common measure is productivity, which is outputs divided by inputs. This can be an important measurement, but it is very easy to distort this. How? Simply by not investing.

Figure 2.3 Changes in strategy from craft to mass production.

The same is true of the accounting ratio – return on net assets. For sure, it makes good sense to map and compare with other competitors how money is being utilized. However, like the productivity ratio, this can be made to look artificially good simply by not investing. Investment in technology cannot be justified by a series of accounting ratios. Such ratios do not account for the cost of not investing.

The biggest problem with such accounting ratios is in rewarding manufacturing management purely on the basis of efficiency and cost minimization, which in turn, encourages high levels of utilization, economies of scale and specialized equipment. These are exactly the wrong parameters of measurement in an era that, as we shall see, includes mass customization and agility. The changes between craft and mass production in relation to strategy is shown in Figure 2.3.

The emergence of the strategic importance of operations

The emergence of the strategic importance of operations

Major changes since the 1970s have undermined mass production, mainly due to increased levels of competition, which have resulted in greater choice for customers. Henry Ford's often-quoted opinion that Ford's customers ‘can have any color of car provided it's black’ is now long gone. Now the customer can have any colour, can have additional customer-specific requirements, and can have it delivered more speedily than ever before.

This shift places greater emphasis on operations capabilities than ever before. However, in some firms manufacturing/operations is still seen as a function and is separate from the business and corporate strategy process. This was common under mass production. The heightened levels of competition in many industries demand flexibility, delivery speed and innovation. D'Aveni (1994) used ‘hypercompetition’ to describe the rapidly escalating competition characterizing many industries. Strategic operations need to be in place in order to deal with such dramatic change.

A number of writers have provided important insight into the changes that need to be made. Skinner (1969, 1974) linked manufacturing operations with strategic decisions made at corporate level. The volume of literature on manufacturing/operations strategy has increased since the mid 1980s, but it is not always clear as to where and when manufacturing strategy might appear in the overall strategic planning process of the firm. Mills et al. (1995, p. 17) summarize the confusion concerning operations strategy manufacturing when they ask:

What is a manufacturing strategy nowadays – is it world-class, lean production, JIT, cells or TQM? Is it none of them, some of them or all of them?’

This perceived confusion with manufacturing strategy is discussed by Kim and Arnold (1996), who likewise conclude that managers often find it hard to distinguish between approaches such as JIT and other issues that might be included in manufacturing strategy. However, important insights have been made by a number of writers. For example, Hayes and Wheelwright (1984) speak of four stages where manufacturing strategy can appear in, and contribute to, the firm's planning process:

![]() Stage 1, which they call internally neutral – the role here is to ensure that manufacturing will not disrupt the intention of the firm and manufacturing's role is purely reactive to an already devised strategy.

Stage 1, which they call internally neutral – the role here is to ensure that manufacturing will not disrupt the intention of the firm and manufacturing's role is purely reactive to an already devised strategy.

![]() Stage 2, externally neutral – the role here is for manufacturing to look externally and to ensure that it is able to achieve parity with competitors.

Stage 2, externally neutral – the role here is for manufacturing to look externally and to ensure that it is able to achieve parity with competitors.

![]() Stage 3, internally supportive – here manufacturing exists to support business strategy. Manufacturing capabilities are audited and the impact of a proposed business strategy upon manufacturing is considered.

Stage 3, internally supportive – here manufacturing exists to support business strategy. Manufacturing capabilities are audited and the impact of a proposed business strategy upon manufacturing is considered.

![]() Stage 4, externally supportive – here manufacturing is central in determining the nature of business strategy and its involvement is much more proactive.

Stage 4, externally supportive – here manufacturing is central in determining the nature of business strategy and its involvement is much more proactive.

Hayes and Wheelwright mapped how manufacturing's role linked with business strategy, from being passive and reactive (stage 1) to a full, pivotal, involvement in the planning stages of business strategy (stage 4). The model is important as a mapping exercise so that firms can realize where manufacturing/operations lines up within the business strategy process.

Hayes and Wheelwright's (1984, p. 32) contribution is also important because it helps to explain what a manufacturing strategy should contain:

. . . manufacturing strategy consists of a sequence of decisions that, over time, enables a business unit to achieve a desired manufacturing structure, infrastructure and set of specific capabilities.

The scope of structural/infrastructure areas that can form part of manufacturing strategy is wide-ranging and can include quality capabilities (including quality requirements that a plant might demand from its supplier base), manufacturing processes, investment requirements, skills audits, capacity requirements, inventory management throughout the supply chain, and new product innovation. Manufacturing strategy is concerned with combining responsibility for resource management (internal factors) as well as achieving business (external) requirements.

Skinner (1985) linked the role of manufacturing capability to the firm's strategic planning, describing manufacturing capabilities – if properly utilized – as a ‘competitive weapon’.

Manufacturing's strategic role in satisfying market requirements has been developed over time. Skinner (1978) introduced the idea of the ‘focused factory’, and he spoke of the need to have a trade-off between cost, quality, delivery and flexibility. The idea of manufacturing strategy as a choice between trade-offs may have been appropriate in the context of 1970s, and was certainly a means of dealing with the perceived confusion in running a plant. As Schonberger stated in 1990, though, as time moved on and competition increased from firms able to satisfy a wide range of customer requirements, the trade-off solution was not a solution after all (Schonberger, 1990, p. 21):

World class strategies require chucking the [trade-off] notion. The right strategy has no optimum, only continual improvement in all things.

Hill (1995) created specific links between corporate, marketing and manufacturing strategies. He stated that firms needed to understand market requirements by differentiating between order-qualifying and order-winning criteria. The former merely allows the firm to compete at all in the market place, since without these the firm would lose orders. However, order-winning criteria are factors that enable the firm to win in the marketplace.

Although Hill's distinction became adopted in manufacturing strategy literature, Spring and Boaden (1997), for example, question the premise ‘how do products win orders in the market?’ – suggesting, as did Brown et al. (2000), that it is the firm (with all of its attendant reputation, experience and architecture) and not just products themselves that wins business. In other words, firms must go beyond the idea of competing purely on products and provide a range of outstanding capabilities including low cost, high process and product quality, speed of delivery, and excellence in service.

The modern era

The modern era

Today highly capable competitors from all over the globe provide more choice to customers than ever before. Various terms used to describe the current era include:

![]() Mass customization, which states the need for volume, combined with recognition of customers’ (or ‘consumers’) wishes.

Mass customization, which states the need for volume, combined with recognition of customers’ (or ‘consumers’) wishes.

![]() Flexible specialization, which relates to the manufacturing strategy of firms (especially small firms) to focus on parts of the value-adding process and collaborate within networks to produce whole products.

Flexible specialization, which relates to the manufacturing strategy of firms (especially small firms) to focus on parts of the value-adding process and collaborate within networks to produce whole products.

![]() Lean production, which came to light in the book The Machine That Changed the World (Womack et al., 1990) (which described the massively successful Toyota Production System) and focuses on the removal of all forms of waste from a system (some of them difficult to see).

Lean production, which came to light in the book The Machine That Changed the World (Womack et al., 1990) (which described the massively successful Toyota Production System) and focuses on the removal of all forms of waste from a system (some of them difficult to see).

![]() Agility, which is an approach that emphasizes the need for an organization to be able to switch frequently from one market-driven objective to another.

Agility, which is an approach that emphasizes the need for an organization to be able to switch frequently from one market-driven objective to another.

![]() Strategic operations, in which the need for the operations to be framed in a strategy is seen as a critical issue in order for firms to compete in the volatile era.

Strategic operations, in which the need for the operations to be framed in a strategy is seen as a critical issue in order for firms to compete in the volatile era.

Regardless of its name, the current competitive era demands high volume and variety together with high levels of quality as the norm, and rapid, ongoing innovation in many markets. It is, as mass production was a hundred years ago, an innovation that makes the system it replaces largely redundant.

Intense competition requires that competencies and capabilities must include flexibility and ‘organizational agility’, whereby a range of dynamic capabilities can be utilized to face future competition. The ability to achieve the wide-ranging requirements of the current era does not come about by luck or chance; it is derived from accumulated learning and know-how gained by the firm over time, and at the core of the current era is a view of operations as strategic. While having a strategic view of operations may not guarantee that firms succeed, treating operations capabilities as a side issue to strategic areas is likely to mean that the firm will suffer in the current era of rapid change and volatility.

The current era has placed ever greater responsibilities on operations managers, and The Economist summarized the position very well (20 June 1998, p. 58):

Manufacturing used to be pretty simple. The factory manager or the production director rarely had to think about suppliers or customers. All he did was to make sure that his machinery was producing widgets at the maximum hourly rate. Once he had worked out how to stick to that ‘standard rate’ of production, he could sit back and relax. Customer needs? Delivery times? Efficient purchasing? That was what the purchasing department and the sales department were there for. Piles of inventory lying around, both raw materials and finished goods? Not his problem. Now it is. The 1980s was the decade of lean production and right-first-time quality management. In the 1990s the game has grown even tougher. Customers are more and more demanding. They increasingly want the basic product to be enhanced by some individual variation, or some special service. Companies sweat to keep up with their demands, in terms both of the actual products and of the way they are delivered.

The role of the operations manager is now more strategic than before, particularly under mass production. For example, Samson and Sohal (1993) argue that:

. . . manufacturing managers must become more than just implementers of engineering and marketing instructions on the shop floor. Raising the status of the manufacturing function involves getting the manufacturing manager involved in the business development/market competitiveness debate. Manufacturing managers need to be interfaced with and have an understanding of the firm's customers

and:

In the world's leading manufacturers, the production management function has become a high-status activity and is the powerhouse that energizes the competitive advantage that the marketing function can achieve in the marketplace.

Agility can be a powerful competitive weapon for the firm. As Roth (1996) states:

The ability to rapidly alter the production of diverse products can provide manufacturers with a distinct competitive advantage. Companies adopting flexible manufacturing technology rather than conventional manufacturing technology can react more quickly to market changes, provide certain economies, enhance customer satisfaction and increase profitability. Research shows the adoption and use of technological bases determines an organization's future level of competitiveness. Corporate strategy based on flexible manufacturing technology enables firms to be better positioned in the battles that lie ahead in the global arena.

However, agility is not just concerned with manufacturing. In services, technology (especially computer technology) has radically altered many of the transformation processes associated with service provision. This applies especially to back-of-house activities – for example, cheque processing in banks, reservations in hotels, and inventory management in retail stores.

The other ‘revolution’ in services might be seen as the opposite of a ‘high technology’– the significant growth of self-service. Many people have seen and continue to see this as a lowering of quality standards as a means of reducing costs. Significant savings in labour cost may be achieved if the customer does things previously done by a service worker. In effect, this is perceived as a trade-off, similar to that described by Skinner. However, increasingly it is being understood that quality is enhanced if customers participate in their own service. For instance, diners who serves themselves from a restaurant salad bar enjoy a product individually customized to their personal tastes, appetite and value perception.

Many firms struggle with equipping operations in a way that will enable the firm to compete successfully against other firms. The result has been that industries are littered with firms who have had to exit because of their incapability within operations.

How do firms make changes to ensure that their operations are strategic? The role of the Chief Executive Officer is crucial here. What has become clear is that, in recent times, world-class firms have Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) who are, at the same time, also Chief Operating Officers (COOs) – as Fortune indicated (21 June 1999, p. 68):

Note how many of today's best CEOs, the master executors, don't even have a COO: Craig Barrett of Intel . . . Michael Dell of Dell, Gerstner of IBM, Nasser of Ford . . . That's a multi-industry all-star team of CEOs who've put themselves squarely in charge of meeting their commitments and getting things done . . . The problem is that our age's fascination with strategy and vision feeds the mistaken belief that developing exactly the right strategy will enable a company to rocket past competitors. In reality that's less than half the battle.

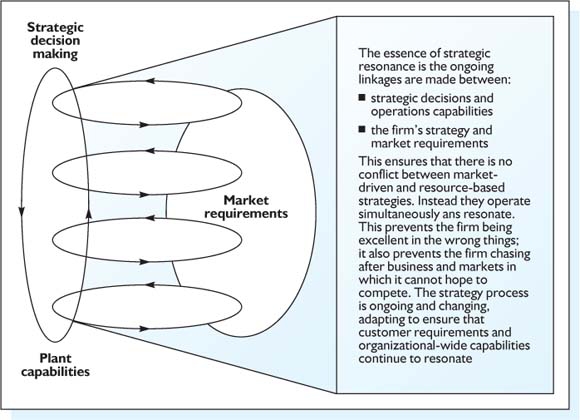

The real battle is in constantly ensuring that strategic resonance takes place between those decisions made at senior levels of the firm and the firm's capabilities; and also between the firm's capabilities and customer requirements. Having strategic operations in place is the means by which strategy becomes operationalized.

Strategic resonance: the key to successful strategy

Strategic resonance: the key to successful strategy

Brown (2000) has coined the term strategic resonance to describe how world-class firms devise and implement strategies. World-class firms do not see strategy as either a market-driven or a resource-based process, but create resonance between the two. World-class firms both seek new market opportunities and have in place capabilities poised to be used. Dell Computers is a perfect example. In Dell and Friedmans’ book Direct from Dell: Strategies that Revolutionized an Industry (1999, p. 25), Michael Dell describes how he reacted to taunts from the revitalized Apple Computer Company:

We reacted by continuing to do what we always have: focusing on the customer, not the competition.

This is more than a bland dismissal of Apple by Dell. Dell knows that his strategy works because market opportunities are met by powerful, strategic operations capabilities (Business Week, 8 March 1999, p. 20):

‘By spending time with your customer where they do business, you can learn more than by bringing them to where you do business’, he [Dell] writes. Visiting British Petroleum Co. in London, for example, Dell watched workers configure their machines with new software and networking capabilities – at considerable cost. BP asked Dell if he could do the work for them. The result was a new multimillion dollar business involving many such customers.

Was this a market-led strategy, or was it resource-based? The answer, of course, is that it is both simultaneously. In other words, strategic resonance had occurred..

World-class firms are those that cause strategic resonance to occur. Strategic resonance is an ongoing, dynamic, strategic process whereby customer requirements and organizational capabilities are in harmony and resonate. Strategic resonance is more than strategic fit – a term that we mentioned earlier to describe the ‘fit’ between the firms’ capabilities and the market that it serves. Strategic resonance goes beyond that. Strategic fit may be likened to a jigsaw where all parts fit together; this is a useful view, but it can have – and this was noted in interviews with key staff in this research – a very static feel to it. In strategic fit it is as if, once the ‘bits’ are in place, the strategic planning is done. By contrast, strategic resonance is a dynamic, organic process, which is about ensuring continuous linkages and harmonization between:

![]() The market and the firm's operations capabilities

The market and the firm's operations capabilities

![]() The firm's strategy and its operations capabilities

The firm's strategy and its operations capabilities

![]() All functions and all levels within the firm.

All functions and all levels within the firm.

Firms need to find and exploit their strategic resonance – between markets and the firm; within the firm itself; and between senior level strategists and plant-level, operations capabilities. Therein lies the problem – sometimes those who are in the position to make strategic decisions know little or nothing about the strategic opportunities and strategic power that lie within its operations’ resources and capabilities. As a result there is no strategic resonance between strategy and operations, and consequently senior level strategists articulate a mission and a strategy that has no chance of being realized. It will not be realized because the firm does not know what the capabilities are in the first place, or the firm simply does not possess the necessary operations know-how and capability, or the firm seems incapable of seeking partnerships with other firms that do.

Figure 2.4 Planning strategic resonance between market requirements and operations capabilities (from Brown, 2000).

Strategic Resonance is illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Service operations strategies

Service operations strategies

Service sector firms face some of the same challenges as manufacturing firms, and some unique challenges of their own.

First, services are increasingly either managed or traded internationally, and so service firms need to devise plans for how this will be accomplished. Where services and manufacturing are closely linked in the overall provision to customers, the role of services can be vital. In the past, companies often located manufacturing facilities in different countries to take advantage of local resources and wage rates and the emphasis was on the manufacturing element. However, today multinational corporations are locating services where they can access highly-trained workers at reasonable costs – for example in India and in Eire.

Such effects can also be observed at the regional level within countries. For example, in the UK many call centres have located in Yorkshire, where local accents have been judged to be the ‘most friendly’ and to come across well over the telephone; others have located in isolated rural areas of Scotland, where there are large untapped resources of an educated workforce without much competing local employment.

Service organizations may choose one of three generic strategies:

1 Customer-oriented focus – providing a wide range of services to a limited range of customers, using a customer-centred database and developing new offerings to existing customers (e.g. Rentokil)

2 Service-oriented focus – providing a focused, ‘limited menu’ of services to a wide range of customers, usually through specialization in a narrow range of services (e.g. Midas Mufflers)

3 Customer- and service-oriented focus – providing a limited range of services to a highly targeted set of customers (e.g. McDonald's).

Ensuring service quality is a key competitive objective for most service organizations. Unlike manufacturing, customer contact in services means that both front-line employees and customers influence the quality and perception of the service. Service failures occur when the service is unavailable, too slow, or does not meet organizational or customer standards. Two ways that companies can mitigate service failures are service guarantees and service recovery.

Many companies now offer service guarantees as a way of ensuring customer satisfaction. For example, overnight document delivery service Federal Express guarantees delivery of packages by 10.30am the morning after the package was mailed, otherwise the entire cost will be refunded.

Although most organizations strive for 100 per cent ‘right-first-time’ performance, occasionally something goes wrong. Service recovery describes how the company makes up for problems with the service. Research suggests that effective service recovery can in fact lead to more loyal customers (quoted in Zeithaml and Bitner, 2000).

One trend in service is to have customers become partners in the service delivery system by transferring at least part of production to them, variously known as co-production or consumerization of production. For example, in France's TGV high-speed passenger train services, customers check themselves in and validate their tickets using ticket machines located on the concourse between the main train station and the platform. Other familiar examples include:

![]() Fast-food restaurants – customers collect their food from the counter, transport it to where they will eat it, and clear away afterwards

Fast-food restaurants – customers collect their food from the counter, transport it to where they will eat it, and clear away afterwards

![]() Petrol stations – customers pump their own petrol and may pay for it at the pump, eliminating all contact with employees

Petrol stations – customers pump their own petrol and may pay for it at the pump, eliminating all contact with employees

![]() Banks – customers use automated teller machines (ATMs) to perform many activities formerly requiring tellers, including cash deposits and withdrawals and account status queries

Banks – customers use automated teller machines (ATMs) to perform many activities formerly requiring tellers, including cash deposits and withdrawals and account status queries

![]() Airlines – customers can order tickets on-line.

Airlines – customers can order tickets on-line.

In becoming part of the production process, making the client productive can take place in four ways. The first way to make clients productive is to involve them in the specification of custom-tailored services. There are many familiar services that rely on customer specification, such as kitchen design.

A second way is to include customers in the production of the service, thus turning them into ‘involuntary unpaid labour’. Most of us have become accustomed to eating at least occasionally in fast-food restaurants, where we (instead of employees) are responsible for clearing tables, etc. In return, these offer (at least in theory) faster service and lower costs, since employees have less work to perform.

A third way is to make the customer responsible for quality control. A popular restaurant trend has been restaurants such as the ‘Mongolian Wok’ chain, where customers select their own ingredients from a buffet, and then hand them over to a chef for stir-frying – they can include their favourite ingredients and exclude those they dislike, rather than accepting a standard range.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

Strategy matters, because without it a firm does not have direction. Consequently, any successes that it may gain will be by fluke. For sure, there are success stories that appear to have been achieved by pure chance – or so the stories would have us believe. However, if you get to the core of the success you will nearly always find that a firm was poised and ready with its capabilities and then met a market opportunity. It was able to respond more quickly, or with better quality or with a greater range of offerings, than its competitors. All of these capabilities are what the firm does, and does via its company-wide operations. This ability to learn, adopt and utilize world-class operations capabilities does not come about by chance; instead it comes about by seeking out and accumulating capabilities. If a firm does not do this, there will be a gap between strategic intent and strategic capability. It is this gap between intent and capability that remains a massive hurdle for firms, and it has cost many CEOs their jobs. CEOs in the modern era will be judged on their ability to understand, develop and utilize world-class operations in a manner that creates advantage – in other words, to use strategic operations. As we shall see in the following cases, some CEOs can do so while others cannot.

Case study

The role of the CEO in managing operations

The following is adapted from Fortune magazine, 21 June 1999:

What got Eckhard Pfeiffer fired? What fault did in Bob Allen? Or Gil Amelio, Bob Stempel, John Akers, or any of the dozens of other chief executives who took public pratfalls in this unforgiving decade? Suppose what brought down all these powerful and undeniably talented executives was just one common failing? It's an intriguing question and one of deep importance not just to CEOs and their boards, but also to investors, customers, suppliers, alliance partners, employees, and the many others who suffer when the top man stumbles . . . Consider the Pfeiffer episode. The pundits opined, as they usually do in these cases, that his problem was with grand-scale vision and strategy. Compaq's board removed the CEO for lack of ‘an Internet vision’, said USA Today. Yep, agreed the New York Times, Pfeiffer had to go because of ‘a strategy that appeared to pull the company in opposite directions’.

But was flawed strategy really Pfeiffer's sin? Not according to the man who led the coup, Compaq Chairman Benjamin Rosen. ‘The change [will not be in] our fundamental strategy – we think that strategy is sound – but in execution’, Rosen said. ‘Our plans are to speed up decision-making and make the company more efficient.’

You'd never guess it from reading the papers or talking to your broker or studying most business books, but what's true at Compaq is true at most companies where the CEO fails. In the majority of cases – we estimate 70 per cent – the real problem isn't the high-concept boners the boffins love to talk about.

It's bad execution. As simple as that: not getting things done, being indecisive, not delivering on commitments . . . It's clear, as well, that getting execution right will only become more crucial. The worldwide revolution of free markets, open economies, and lowered trade barriers and the advent of e-commerce has made virtually every business far more brutally competitive . . . Yet you needn't be ruthless to get things done. Ron Allen's willingness to swing the ax so antagonized Delta's work force that the board asked him to leave. When Lou Gerstner parachuted in to fix the shambles John Akers had left of IBM, famously declaring that ‘the last thing IBM needs right now is a vision’, he focused on execution, decisiveness, simplifying the organization for speed, and breaking the gridlock. Many expected heads to roll, yet initially Gerstner changed only the CFO, the HR chief, and three key line executives – and he has multiplied the stock's value tenfold . . . GE's Jack Welch loves to spot people early, follow them, grow them, and stretch them in jobs of increasing complexity. ‘We spend all our time on people’, he says. ‘The day we screw up the people thing, this company is over.’ He receives volumes of information – good and bad, from multiple sources – and he and his senior team track executives’ progress in detail through a system of regular reviews. His written feedback to subordinates is legendary: specific, constructive, to the point. Of course some come up short. When Welch committed the company to achieving six-sigma quality a few years ago, he evaluated how the beliefs of high-level executives aligned with six-sigma values. He confronted those who weren't on board and told them GE was not the place for them.

This continual pruning and nurturing gives GE a powerful competitive advantage few companies understand and even fewer achieve . . . Decision gridlock can happen to anyone, but it happens most often to CEOs who've spent a career with one company, especially a successful one. The processes have worked, they're part of the company's day-to-day life – so it takes real courage to blow them up. Listen to Elmer Johnson, a top GM executive, describe this problem to the executive committee: ‘The meetings of our many committees and policy groups have become little more than time-consuming formalities. The outcomes are almost never in doubt . . . There is a dearth of discussion, and almost never anything amounting to lively consideration . . . It is a system that results in lengthy delays and faulty decisions by paralyzing the operating people . . .’. That was in 1988, during Roger Smith's troubled tenure, and the problem persisted through Stempel's brief reign. Neither man could break the process machine, and both must be considered failed CEOs . . . Keeping track of all critical assignments, following up on them, evaluating them – isn't that kind of . . . boring? We may as well say it: Yes. It's boring. It's a grind. At least, plenty of really intelligent, accomplished, failed CEOs have found it so, and you can't blame them. They just shouldn't have been CEOs.

The big problem for them is not brains or even ability to identify the key problems or objectives of the company. When Kodak ousted Kay Whitmore, conventional wisdom said it was because he hadn't answered the big strategic questions about Kodak's role in a digital world. In fact, Kodak had created, though not publicized, a remarkably aggressive plan to remake itself as a digital imaging company. Whitmore reportedly embraced it. But he couldn't even begin to make it happen. Same story with William Agee at Morrison Knudsen – plausible strategy, no execution.

The problem for these CEOs is in the psyche. They find no reward in continually improving operations . . . Any way you look at it, mastering execution turns out to be the odds-on best way for a CEO to keep his job. So what's the right way to think about that sexier obsession, strategy? It's vitally important – obviously. The problem is that our age's fascination with strategy and vision feeds the mistaken belief that developing exactly the right strategy will enable a company to rocket past competitors. In reality, that's less than half the battle.

This shouldn't be surprising. Strategies quickly become public property. Ask Michael Dell the source of his competitive advantage, and he replies, ‘Our direct business model’. Okay, Michael, but that's not exactly a secret. Everyone has known about it for years. How can it be a competitive advantage? His answer: ‘We execute it. It's all about knowledge and execution’. Toyota offers anyone, including competitors, free, in-depth tours of its main US operations – including product development and distributor relations. Why? The company knows visitors will never figure out its real advantage, the way it executes. Southwest Airlines is the only airline that has made money every year for the past 27 years. Everyone knows its strategy, yet no company has successfully copied its execution.

Key questions

1 From the above case, why is it so important that the Chief Executive Officer really understands operations management?

2 Why is it vital for operations and marketing to understand each other's roles within the firm?

3 Why is there still conflict between business and operations strategies?

Key terms

Agile production

Manufacturing Strategy

Mass customization

Service operations strategies

Strategy

Strategic operations

References

Brown, S. (1996). Strategic Manufacturing for Competitive Advantage. Prentice Hall.

Brown, S. (2000). Manufacturing the Future – Strategic Resonance for Enlightened Manufacturing. Financial Times Books.

Brown, S., Lamming, R., Bessant, J. and Jones, P. (2000). Strategic Operations Management. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Business Week (1999). 8 March.

D'Aveni, R. (1994). Hypercompetition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering. Free Press.

Dell, M. and Friedman, C. (1999). Direct From Dell: Strategies That Revolutionized an Industry. Harper Business.

The Economist (1998). June 20.

Financial Times (1997). November 12.

Fortune (1999). Why CEOs fail: It's rarely for lack of smarts or vision. Most unsuccessful CEOs stumble because of one simple, fatal shortcoming. Fortune, 21 June, 139(12), 68.

Hayes, R. and Wheelwright, S. (1984). Restoring Our Competitive Edge. Wiley & Sons.

Hill, T. (1995). Manufacturing Strategy. Macmillan.

Johnson, G. and Scholes, K. (1999). Exploring Corporate Strategy, 5th edn. Prentice Hall.

Kim, J. S. and Arnold, P. (1996). Operationalizing manufacturing strategy: An exploratory study of constructs and linkage. Int. J. Operations Product. Man., 16(12), 45–65.

Mills, J. F., Neely, A., Platts, K. and Gregory, M. (1995). A framework for the design of manufacturing strategy processes: toward a contingency approach. Int. J. Operations Product. Man., 15(4), 17–49.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, 1996 reprint. Oxford University Press.

Peters, T. and Waterman, R. H. (1982). In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America's Best Run Companies. Harper & Row.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy. Free Press.

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive Advantage. Free Press.

Roth, A. V. (1996). Achieving strategic agility through economics of knowledge. Strategy Leadership, 24(2), 21–32.

Samson, D. and Sohal, A. (1993). Manufacturing myopia and strategy in the manufacturing function: a problem driven agenda. Special issue on ‘Manufacturing technology: diffusion, implementation and management’. Int. J. Technol. Man., 8(3/4/5), 216–29.

Schonberger, R. (1990). Building a Chain of Customers. Hutchinson Business Books.

Skinner, W. (1969). Manufacturing – the missing link in corporate strategy. Harvard Bus. Rev., May–June, 136–45.

Skinner, W. (1974). The focused factory. Harvard Bus. Rev., May–June, 113–21.

Skinner, W. (1978). Manufacturing in the Corporate Strategy. John Wiley & Sons.

Skinner, W. (1985). Manufacturing, The Formidable Competitive Weapon. John Wiley & Sons.

Spring, M. and Boaden, R. (1997). One more time: how do you win orders?: a critical reappraisal of the Hill manufacturing strategy framework. Int. J. Operations Prod. Man., 17(8)

Spring, M. and Dalrymple, J. F. (2000). Product customisation and manufacturing strategy. Int. J. Operations Product. Man., 20(4), 451–70.

Verdin, P. and Williamson, P. (1994). Successful strategy: stargazing or self-examination? Eur. Man. J., 12(1), 10–19.

Whittington, R. (1993). What is Strategy – and Does it Matter? Routledge.

Womack, J., Jones, D. and Roos, D. (1990). The Machine That Changed the World. Rawson Associates. Womack, J., Jones, D. and Roos, D. (1990). The Machine That Changed the World. Rawson Associates.

Zeithaml, V. and Bitner, M. J. (2000). Services Marketing, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill.

Further reading

Anderson, J., Schroeder, R. and Cleveland, G. (1991). The process of manufacturing strategy. Int. J. Product. Operations Man., 11(3).

Clark, K. (1996). Competing through manufacturing and the new manufacturing paradigm: is manufacturing strategy passé? Product. Operations Man., 5(1).

Collis, D. and Montgomery, C. (1995). Competing on resources: strategy in the 1990s. Harvard Bus. Rev., 73(4), 118–28..

Corsten, H. and Will, T. (1994). Simultaneously supporting generic competitive strategies by production management. Technovation, 14(2), 111–20.

Hayes, R. (1985). Strategic planning: forward in reverse? Harvard Bus. Rev., Nov–Dec, 111–19.

Hayes, R. and Pisano, G. (1994). Beyond world-class: the new manufacturing strategy. Harvard Bus. Rev., Jan–Feb, 77–86.

Hayes, R. and Pisano, G. (1996). Manufacturing strategy: at the intersection of two paradigm shifts. Product. Operations Man., 5(1).

Mills, J., Platts, K. and Gregory, M. (1995). A framework for the design of manufacturing strategy process. Int. J. Operations Product. Man., 15(4), 17–49.

Voss, C. (1992). Manufacturing Strategy. Chapman and Hall.