6

Motivation and Performance

Work, family, and leisure are highly intertwined in our busy multitasking world. There's a lot to balance in the quest for life and career satisfaction. Things go a lot better for people and organizations when work activities and outcomes fit well with individual needs and responsibilities. ![]()

What's Inside?

![]() Bringing OB to LIFE

Bringing OB to LIFE

PAYING OR NOT PAYING FOR KIDS' GRADES

![]() Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

WANT VACATION? NO PROBLEM, TAKE AS MUCH AS YOU WANT

![]() Checking Ethics in OB

Checking Ethics in OB

SNIFFLING AT WORK TAKES ITS TOLL

![]() Finding the Leader in You

Finding the Leader in You

SARA BLAKELY LEADS SPANX FROM IDEA TO BOTTOM LINE

![]() OB in Popular Culture

OB in Popular Culture

SELF-MANAGEMENT AND SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE

![]() Research Insight

Research Insight

RACIAL BIAS MAY EXIST IN SUPERVISOR RATINGS OF WORKERS

Chapter at a Glance

- What Is the Link Between Motivation, Performance, and Rewards?

- What Are the Essentials of Performance Management?

- How Do Job Designs Influence Motivation and Performance?

- What Are the Motivational Opportunities of Alternative Work Arrangements?

Motivation, Rewards, and Performance

![]() EMPLOYEE VALUE PROPOSITION AND FIT

EMPLOYEE VALUE PROPOSITION AND FIT

INTEGRATED MODEL OF MOTIVATION

INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC REWARDS ![]() PAY FOR PERFORMANCE

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE

Motivation is defined as forces within the individual that account for the level and persistence of an effort expended at work. And because motivation is a property of the individual, we basically motivate ourselves. All managers and team leaders or parents and teachers can do is try to create environments that offer other individuals appealing sources of motivation. Whether they respond positively or not is up to them. But, one way to unlock this motivational potential is to provide opportunities to earn rewards that match well with individual needs and goals.

Motivation accounts for the level and persistence of a person's effort expended at work.

Employee Value Proposition and Fit

Employee Value Proposition and Fit

Perhaps the best place to start any discussion of the link between motivation, rewards, and performance is the concept of an employee value proposition, or EVP Think of it as an exchange of value, what the organization offers the employee in return for his or her work contributions.1 The value offered by the individual includes things like effort, loyalty, commitment, creativity, and skills. The value offered by the employer includes things like pay, benefits, meaningful work, flexible schedules, and personal development opportunities. It is common to call this exchange of values the psychological contract.

The employee value proposition, or EVP, is an exchange of value in what the organization offers the employee in return for his or her work contributions.

When everything comes together in an EVP and the psychological contract is in balance, the foundations for motivation are well set—not perfect yet, but well set. The key starting point is that each party perceives the exchange of values as fair and that it is getting what it needs from the other. Any perceived imbalance is likely to cause problems. From the individual's side, a perceived lack of inducements from the employer may reduce motivation and ultimately poor performance. From the employer's side, a perceived lack of contributions from the individual may cause a loss of confidence in and commitment to the employee, and reduced rewards for work delivered.

The foundation for a healthy and positive employee value proposition is “fit.” Person-job fit is the extent to which an individual's skills, interests, and personal characteristics match well with the requirements of the job. Person-organization fit is the extent to which an individual's values, interests, and behaviors are consistent with the culture of the organization. A poor fit in either case increases the likelihood that imbalance will creep into the EVP. The importance of a good fit to the employee value proposition is highlighted to the extreme at Zappos.com. Believe it or not, if a new employee is unhappy with the firm after going through initial training, Zappos pays them to quit. At last check the “bye-bye bounty” was $4,000, and between 2 and 3 percent of new hires were taking it each year.2

Person-job fit is the extent to which an individual's skills, interests, and personal characteristics match well with the requirements of the job.

Person-organization fit is the extent to which an individual's values, interests, and behaviors are consistent with the culture of the organization.

Integrated Model of Motivation

Integrated Model of Motivation

Wouldn't it be nice if we all worked with a great employee value proposition and could connect with our jobs and organizations in positive and inspirational ways? In fact, there are lots of great workplaces out there. And, they become great because people and practices throughout the organization turn members on to their jobs rather than off of them. Making this happen requires a good understanding of motivation, a true appreciation for diversity and individual differences, and the ability to make rewards for good work truly meaningful.

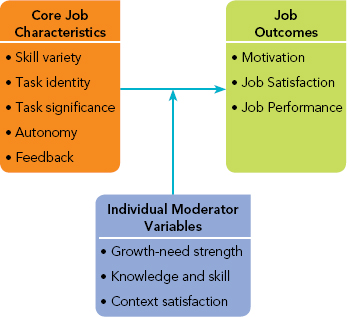

FIGURE 6.1 An integrated model of individual motivation to work.

Figure 6.1 outlines an integrated model of motivation that ties together the basic effort-performance-rewards relationship. The figure shows job performance and satisfaction as separate but interdependent work results. Performance is influenced by individual attributes such as ability and experience; organizational support comes from things such as goals, resources, and technology; and effort is the willingness of people to work hard at what they are doing. The individual experiences satisfaction when the rewards received for work accomplishments are perceived as both performance contingent and equitable.

Double-check Figure 6.1 and locate where various motivation theories come into play. Reinforcement theory highlights performance contingency and immediacy in determining how rewards affect future performance. Equity theory points to the influence on behavior of the perceived fairness of rewards. Content theories offer insight into individual needs that can give motivational value to the possible rewards. And, expectancy theory is central to the effort-performance-rewards linkage.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards

The typical reward systems of organizations offer a mix both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. Intrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that the individual receives directly as a result of task performance. Think of them as the reasons we do things just to enjoy them—play a sport, listen to certain music, and even do certain jobs. A feeling of achievement after completing a particularly challenging task is an example. Yves Chouinard, founder and CEO of Patagonia, Inc., puts it this way: “It's easy to go to work when you get paid to do what you love to do.”3 One of the most important things to remember about intrinsic rewards is that we give them to ourselves. Their positive impact doesn't require anyone else—boss or team leader included—to be involved.

Intrinsic rewards are valued outcomes received as internal enjoyment of task performance.

Extrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that are given to an individual or a group by another person. We don't get them by ourselves; someone else has to be the provider. Common extrinsic rewards include symbolic gestures, such as praise for a job well done, or material perks, such as pay raises or bonuses and so on. All such rewards have to be well managed if they are to have positive motivational impact. And the process can be tricky. How often have you heard someone say, “I'll do the minimum to keep the pay and benefits of this job, but that's it,” or “For what I get paid with not even a thank-you, this job is hardly worth the effort I put into it.”

Extrinsic rewards are valued outcomes received from an external source or person.

Pay for Performance

Pay for Performance

Pay is a common and often talked about extrinsic reward. It's also an especially complex one that may not always deliver the hoped-for results. When pay functions well, it can help an organization attract and retain highly capable workers. It can also help satisfy and motivate these workers to work hard to achieve high performance. But when something goes wrong with pay, the results may decrease motivation performance. Pay dissatisfaction often shows up as bad attitudes, increased absenteeism, intentions to leave and actual turnover, poor organizational citizenship, and even adverse impacts on employees' physical and mental health.

The research of scholar and consultant Edward Lawler generally concludes that pay only serves as a motivator when high levels of job performance are viewed as the paths through which high pay can be achieved.4 This is the logic of performance-contingent pay, or pay for performance, where you earn more and earn less when you produce less. Organizations pursue various options when implementing performance-contingent pay systems.

The essence of performance-contingent pay is that you earn more when you produce more and earn less when you produce less.

Merit Pay It is most common to talk about pay for performance in respect to merit pay, a compensation system that directly ties an individual's salary or wage increase to measures of performance accomplishments during a specified time period.

Merit pay links an individual's salary or wage increase directly to measures of performance accomplishment.

Although the concept of merit pay is compelling, a survey by the Hudson Institute demonstrates that it is more easily said than done. When asked if employees who perform better really get paid more, only 48 percent of managers and 31 percent of nonmanagers responded with agreement. When asked if their last pay raise had been based on performance, 46 percent of managers and just 29 percent of nonmanagers said yes.5 In fact, surveys often show that people do not believe their pay is an adequate reward for a job well done.6

In order to work well a merit pay plan should create a belief among employees that the way to achieve high pay is to perform at high levels. This means that the merit system should be based on realistic and accurate measures of work performance. It means that the merit system should clearly discriminate between high and low performers in the amount of pay increases awarded. It also means that any “merit” aspects of a pay increase are clearly and contingently linked with the desired performance.

Bonuses Some employers award cash bonuses as extra pay for performance that meets certain benchmarks or is over and above expectations. The bonus becomes “cash in hand” without raising the base salary or wage rate. This practice is especially common in senior executive ranks. However, a current trend is to extend bonus opportunities to workers at all levels. Employees at Applebee's, for example, may earn “Applebucks”—small cash bonuses that are given to reward performance and increase loyalty to the firm.7

Bonuses are extra pay awards for special performance accomplishments.

Gain Sharing and Profit Sharing Another way to link pay with performance is gain sharing. This gives workers the opportunity to earn more by receiving shares of any productivity gains that they help to create at the team or work unit levels. An alternative is profit sharing, which rewards workers for contributions to increased organizational profits.8 Both gain-sharing and profit-sharing plans are supposed to create a greater sense of personal responsibility for performance improvements and increase motivation to work hard. They are also supposed to encourage cooperation and teamwork to increase productivity.9

Gain sharing rewards employees in some proportion to productivity gains.

Profit sharing rewards employees in some proportion to changes in organizational profits.

Stock Options and Employee Stock Ownership Some companies offer employees stock options that give the owner the right to buy shares of stock at a future date at a fixed or “strike” price.10 The expectation is that because employees gain financially as the stock price increases, those with stock options will be highly motivated to do their best so that the firm performs well. In employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), companies allow stock to be purchased by employees at a price below market value. The incentive value is like the stock options: Employee owners are expected to work hard so that the organization will perform well, the stock price will rise, and, as owners, they will benefit from the gains. Of course, there are risks to both options and stock ownership since a firm's stock prices can fall in the future as well as rise.11

Stock options give the right to purchase shares at a fixed price in the future.

Employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) give stock to employees or allow them to purchase stock at special prices.

Skill-Based Pay Skill-based pay rewards people for acquiring and developing job-relevant skills. Pay systems of this sort pay people for the mix and depth of skills they have, not for the particular job assignment they hold. The expected motivational advantages include more willingness to engage in cross-training to learn other jobs in a team or work unit as well as to take on more self-management responsibilities, thus reducing the need to pay for more supervisors.12

Skill-based pay rewards people for acquiring and developing job-relevant skills.

Motivation and Performance Management

![]() PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT PROCESS

PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT PROCESS

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT APPROACHES AND ERRORS

PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT METHODS

If you want to get hired by Procter & Gamble and get rewarded by advancements to upper management, you had better be good. Not only is the company highly selective in hiring; it also carefully tracks the performance of every manager in every job they are asked to do. The firm always has at least three performance-proven replacements ready to fill any vacancy that occurs. By linking performance to career advancement, motivation to work hard is built into the P&G management model.13

The approach followed by P&G can be highly motivating to those who want to work hard, advance in rank, and have successful top executive careers. However, we shouldn't underestimate the challenge of implementing this type of performance-based reward system. Such systems falter and fail to deliver desired results when the process and/or the performance measurement isn't respected by everyone involved.

Performance Management Process

Performance Management Process

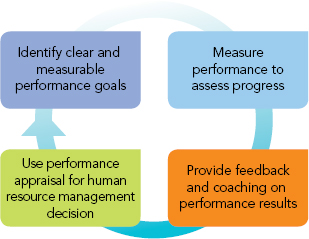

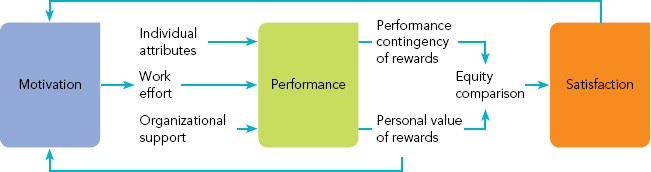

The foundations for performance management are shown in Figure 6.2. And if the process is to work well, everyone involved must have good answers to both the “Why?” and the “What?” questions.

The “Why?” question in performance management is “What is the purpose?” Performance management serves an evaluation purpose when it lets people know where their actual performance stands relative to objectives and standards. Such an evaluation feeds into decisions that allocate rewards and otherwise administer the organization's human resource management systems. Performance management serves a developmental purpose when it provides insights into individual strengths and weaknesses. This can be used to plan helpful training and career development activities.

FIGURE 6.2 Four steps in the performance management process.

The “What?” question in performance management is “What is being measured?” It takes us back to the adage “What gets measured happens”—that is, people tend to do what they know is going to be measured. Given this, we have to make sure we are measuring the right things in the right ways in the performance management process. If a dean wants faculty members to be great teachers, for example, teaching has to be measured in valid ways and rewards tied to the results. Of course, the definition of “great” teaching and the measurement of it are both open to controversy. This is one reason we often talk about the importance of teaching while rewarding faculty members for easier-to-measure research output.

Performance Measurement Approaches and Errors

Performance Measurement Approaches and Errors

Performance measurements should be based on clear criteria, be accurate and defensible in differentiating between high and low performance, and be useful as feedback that can help improve performance in the future. Yet, talking about good measurement is easier than actually doing it. It's good to use output measures that assess what is accomplished in respect to concrete work results. But when measuring outputs is hard, activity measures that assess work inputs in respect to activities tried and efforts expended are often used as replacements. An example might be to use the number of customer visits made per day—an activity measure—to assess a salesperson, instead of or in addition to counting the number of actual sales made—an output measure.

Output measures of performance assess achievements in terms of actual work results.

Activity measures of performance assess inputs in terms of work efforts.

Regardless of the method being employed, any performance assessment system should satisfy two criteria. First, the measures should past the test of reliability. This means they provide consistent results each time they are used for the same person and situation. Second, the measures should pass the test of validity. This means that they actually measure something of direct relevance to job performance. The following are examples of measurement errors that can reduce the reliability or validity of any performance assessment.14

Reliability means a performance measure gives consistent results.

Validity means a performance measure addresses job-relevant dimensions.

- Halo error—results when one person rates another person on several different dimensions and gives a similar rating for each dimension.

Common performance measurement errors

- Leniency error—just as some professors are known as “easy A's,” some managers tend to give relatively high ratings to virtually everyone under their supervision; the opposite is strictness error—giving everyone a low rating.

- Central tendency error—occurs when managers lump everyone together around the average, or middle, category; this gives the impression that there are no very good or very poor performers on the dimensions being rated.

- Recency error—occurs when a rater allows recent events to influence a performance rating over earlier events; an example is being critical of an employee who is usually on time but shows up one hour late for work the day before his or her performance rating.

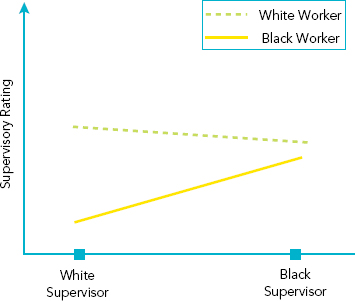

- Personal bias error—displays expectations and prejudices that fail to give the jobholder complete respect, such as showing racial bias in ratings.

Performance Assessment Methods

Performance Assessment Methods

The formal procedure or event that evaluates a person's work performance is often called performance review, performance appraisal, or performance assessment. A variety of methods can be used. But, each has strengths and weaknesses that may make it a better choice in some situations than in others.15

Comparative Methods Comparative methods of performance assessment identify one worker's standing relative to others. Ranking is the simplest approach and is done by rank ordering each individual from best to worst on overall performance or on specific performance dimensions. Although relatively simple to use, this method can be difficult when many people must be considered. An alternative is the paired comparison in which each person is directly compared with every other one. A person's final ranking is determined by the number of pairs for which she or he emerges as the “winner.” Yet another alternative is forced distribution. It forces a set percentage of all persons being assessed into predetermined performance categories, such as outstanding, good, average, and poor. For example, it might be that a team leader must assign 10 percent of members to “outstanding” another 10 percent to “poor,” and another 40 percent each to “good” and “average.” One goal of this method is to eliminate tendencies to rate everyone about the same.

Ranking in performance appraisal orders each person from best to worst.

Paired comparison in performance appraisal compares each person with every other one.

Forced distribution in performance appraisal forces a set percentage of persons into predetermined rating categories.

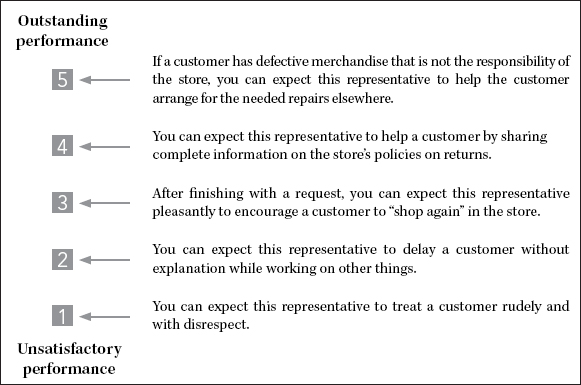

FIGURE 6.3 Sample behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS) for a customer service representative.

Rating Scales Graphic rating scales list a variety of performance dimensions, such as quality or quality of work, or personal traits, such as punctuality or diligence that an individual is expected to exhibit. The scales allow the manager to easily assign the individual scores on each dimension, but the descriptions are often very generalized and lack solid performance links to a given job. The behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS) adds more sophistication by linking ratings to specific and observable job-relevant behaviors. These include descriptions of superior and inferior performance. The sample BARS for a customer service representative in Figure 6.3 shows a focus on discriminating among very specific work behaviors. This specificity makes the BARS more valuable for both evaluation and development purposes.16

Graphic rating scales in performance appraisal assign scores to specific performance dimensions.

The behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS) links performance ratings to specific and observable job behaviors.

Critical Incident Diary Critical incident diaries are written records that give examples of a person's work behavior that leads to either unusual performance success or failure. The incidents are typically recorded in a diary-type log that is kept daily or weekly according to predetermined dimensions. This approach is excellent for employee development and feedback. However, because it consists of qualitative statements rather than quantitative ratings, it is more debatable as an evaluation tool. This is why the critical incident technique is often used in combination with one of the other methods.

Critical incident diaries record actual examples of positive and negative work behaviors and results.

360° Review Many organizations now make assessments based on a combination of feedback from a person's bosses, peers, and subordinates, internal and external customers, and self-ratings. Known as the 360° review, or 360° assessment, it is quite common in today's team-oriented organizations. A typical approach asks the jobholder to complete a self rating and meet with a set of 360° participants to discuss it as well as their ratings. The jobholder learns from how well one's self-rating compares with the viewpoints of others, and the results are useful for both evaluation and development purposes.

A 360° review or assessment gathers feedback from a jobholder's bosses, peers, and subordinates, internal and external customers, and self-ratings.

New technologies allow 360° feedback to be continuous rather than periodic. Accenture uses a computer program called Performance Multiplier that allows users to post projects, goals, and status updates for review by others. And Microsoft-Rypple software allows users to post assessment questions in 140 characters or less. Examples might be—“What did you think of my presentation?” or “How could I have run that meeting better?” Anonymous responses are compiled by the program, and the 360° feedback is then sent to the person posting the query.17

Motivation and Job Design

![]() SCIENTIFIC MANAGEMENT

SCIENTIFIC MANAGEMENT ![]() JOB ENLARGEMENT AND JOB ROTATION

JOB ENLARGEMENT AND JOB ROTATION

JOB ENRICHMENT ![]() JOB CHARACTERISTICS MODEL

JOB CHARACTERISTICS MODEL

When it comes to motivation, we might say that nothing beats a good person-job fit. A match of job requirements with individual abilities and needs is often a high satisfaction and high performance combination. By contrast, a bad person-job fit is likely to result in poor motivation and performance problems. You might think of the goal this way:

Person + Good Job Fit = High Motivation

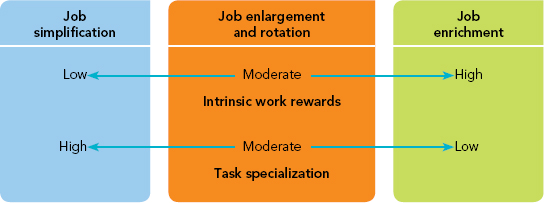

Job design is the process of planning and specifying job tasks and work arrangements.18 Figure 6.4 shows how three alternative job design approaches differ in the way tasks are defined and availability of intrinsic rewards. The “best” job design is one that meets organizational performance requirements, offers a good fit with individual skills and needs, and provides opportunities for job satisfaction.

Job design is the process of specifying job tasks and work arrangements.

Scientific Management

Scientific Management

The history of scholarly interest in job design can be traced in part to Frederick Taylor's work with scientific management in the early 1900s.19 Taylor and his contemporaries wanted to create management and organizational practices that would increase people's efficiency at work. Their approach was to study a job carefully, break it into its smallest components, establish exact time and motion requirements for each task to be done, and then train workers to do these tasks in the same way over and over again. Taylor's principles of scientific management can be summarized as follows:

Taylor's scientific management used systematic study of job components to develop practices to increase people's efficiency at work.

FIGURE 6.4 A continuum of job design strategies.

- Develop a “science” for each job that covers rules of motion, standard work tools, and supportive work conditions.

- Hire workers with the right abilities for the job.

- Train and motivate workers to do their jobs according to the science.

- Support workers by planning and assisting their work using the job science.

Today, the term job simplification is used to describe a scientific management approach that standardizes work procedures and employs people in routine, clearly defined, and highly specialized tasks. The machine-paced automobile assembly line is a classic example. Why is it used? The answer is to increase operating efficiency. Job simplification reduces the number of skills required, allows for hiring low-cost labor, keeps the need for job training to a minimum, and focuses expertise on repetitive tasks. Why is it often criticized? Jobs designed this way come with potential disadvantages—lower work quality, high rates of absenteeism and turnover, and demands for ever-higher wages to compensate for unappealing work. One response is more automation to replace people with technology. In automobile manufacturing, for example, robots now do many different kinds of work previously accomplished with human labor.

Job simplification standardizes work to create clearly defined and highly specialized tasks.

Job Enlargement and Job Rotation

Job Enlargement and Job Rotation

Although job simplification makes the limited number of tasks easier to master, the repetitiveness of the work can reduce motivation. This has prompted alternative job design approaches that try to make jobs more interesting by adding breadth to the variety of tasks performed.

Job enlargement increases task variety by combining into one job two or more tasks that were previously assigned to separate workers. Sometimes called horizontal loading, this approach increases job breadth by having the worker perform more and different tasks, but all at the same level of responsibility and challenge.

Job enlargement increases task variety by combining into one job two or more tasks that were previously assigned to separate workers.

Job rotation increases task variety by periodically shifting workers among jobs involving different tasks. Also a form of horizontal loading, the responsibility level of the tasks stays the same. The rotation can be arranged according to almost any time schedule, such as hourly, daily, or weekly schedules. An important benefit of job rotation is training. It allows workers to become more familiar with different tasks and increases the flexibility with which they can be moved from one job to another.

Job rotation increases task variety by periodically shifting workers among jobs involving different tasks.

Job Enrichment

Job Enrichment

When it comes to job rotation and enlargement, psychologist Frederick Herzberg asks: “Why should workers become motivated when one or more ‘meaningless’ tasks are added to previously existing ones or when work assignments are rotated among equally ‘meaningless’ tasks?”20 He recommends job enrichment. It designs job that create opportunities to experiene responsibility, achievement, recognition, and personal growth. This is done by vertical loading that moves into a job many planning and evaluating tasks normally performed by supervisors. The increased job depth provides pathways to higher-order need satisfaction, and is supposed to increase both motivation and performance.

Job enrichment builds high-content jobs that involve planning and evaluating duties normally done by supervisors.

Job Characteristics Model

Job Characteristics Model

OB scholars have been reluctant to recommend job enrichment as a universal approach to job design. There are just too many individual differences among people at work for it to solve all performance and satisfaction problems. Their answer to the question “Is job enrichment for everyone?” is a clear “No.” Present thinking focuses more on a diagnostic and contingency approach to job design. A good example is the job characteristics model developed by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham.21

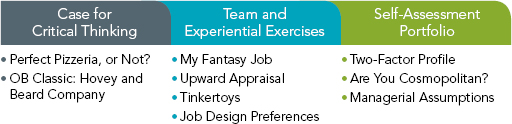

Core Characteristics Figure 6.5 shows how the Hackman and Oldham model informs the process of job design. The higher a job scores on each of the following five core characteristics, the higher its motivational potential and the more it is considered to be enriched:22

- Skill variety—the degree to which a job includes a variety of different activities and involves the use of a number of different skills and talents

Five core job characteristics

Five core job characteristics - Task identity—the degree to which the job requires completion of a “whole” and identifiable piece of work, one that involves doing a job from beginning to end with a visible outcome

- Task significance—the degree to which the job is important and involves a meaningful contribution to the organization or society in general

- Autonomy—the degree to which the job gives the employee substantial freedom, independence, and discretion in scheduling the work and determining the procedures used in carrying it out

- Job feedback—the degree to which carrying out the work activities provides direct and clear information to the employee regarding how well the job has been done

FIGURE 6.5 Job design considerations according to the job characteristics model.

A job's motivating potential can be raised by combining tasks to create larger jobs, opening feedback channels to enable workers to know how well they are doing, establishing client relationships to experience such feedback directly from customers, and employing vertical loading to create more planning and controlling responsibilities. When the core characteristics are enriched in these ways, the job creates what is often called psychological empowerment—a sense of personal fulfillment and purpose that arouses one's feelings of competency and commitment to the work.23 Figure 6.5 identifies three critical psychological states that have a positive impact on individual motivation, performance, and satisfaction: experienced meaningfulness of the work, experienced responsibility for the outcomes of the work, and knowledge of actual results of the work.

Moderator Variables The five core job characteristics do not affect all people in the same way. Rather than accept the notion that enriched jobs should be good for everyone, Hackman and Oldham take a contingency view that suggests enriched jobs will lead to positive outcomes only for those persons who are a good match for them—the person-job fit issue again.

“Fit” in the job characteristics model is based on the three moderators shown in Figure 6.5. The first is growth-need strength, or the degree to which a person desires the opportunity for self-direction, learning, and personal accomplishment at work. The expectation here is that people high in growth-need strengths will respond positively to enriched jobs, whereas people low in growth-need strengths will find enriched jobs to be sources of anxiety. The second moderator is knowledge and skill. People whose capabilities fit the demands of enriched jobs are predicted to feel good about them and perform well. Those who are inadequate or who feel inadequate in this regard are likely to experience difficulties. The third moderator is context satisfaction, or the extent to which an employee is satisfied with aspects of the work setting such as salary, quality of supervision, relationships with co-workers, and working conditions. In general, people who are satisfied with job context are more likely to do well in enriched jobs.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

Research Concerns and Questions Experts generally agree that the job characteristics model and its diagnostic approach are useful but not perfect, guides to job design.24 One concern is whether or not jobs have stable and objective characteristics to which individuals will respond predictably and consistently over time.25 It's quite possible that individual needs and task perceptions are a result of socially constructed realities. Suppose, for example, that several of your friends tell you that the instructor for a course is bad, the content is boring, and the requirements involve too much work. You may then think that the critical characteristics of the class are the instructor, the content, and the workload, and that they are all bad. All of this may substantially influence the way you perceive your instructor and the course, and the way you deal with the class-regardless of the core characteristics discussed in the Hackman and Oldham model.

Finally, research provides the following answers for three common questions about job enrichment and its applications. (1) Should everyone's job be enriched? The answer is clearly “No.” The logic of individual differences suggests that not everyone will want an enriched job. Individuals most likely to have positive reactions to job enrichment are those who need achievement, who exhibit a strong work ethic, or who are seeking higher-order growth-need satisfaction at work. Job enrichment also appears to work best when the job context is positive and when workers have the abilities needed to do the enriched job. Costs, technological constraints, and workgroup or union opposition may also make it difficult to enrich some jobs. (2) With so much attention on teams in organizations today, can job enrichment apply to groups? The answer is “Yes.” The result is called a self managing team. (3) For those who don't want an enrichedjob, what can be done to make their work more motivating? One answer rests in the following section and its focus on alternative work schedules. Even if the job content can't be changed, a redesign of the job context or setting may have a positive impact on motivation and performance.

Alternative Work Schedules

![]() COMPRESSED WORKWEEKS

COMPRESSED WORKWEEKS ![]() FLEXIBLE WORKING HOURS

FLEXIBLE WORKING HOURS

JOB SHARING ![]() TELECOMMUTING

TELECOMMUTING ![]() PART-TIME WORK

PART-TIME WORK

Another way that organizations are reshaping employee value propositions is through alternative work arrangements that do away with the traditional forty-hour weeks and nine-to-five schedules where work is done at the place of business. New alternatives are designed to improve satisfaction by helping employees balance the demands of work with their nonwork lives.26 The value from the employee side is more support for work-life balance by a “family-friendly” employer.

If you have any doubts at all about the forces at play, consider these facts: 78 percent of American couples are dual wage earners; 63 percent believe they don't have enough time for spouses and partners; 74 percent believe they don't have enough time for their children; 35 percent are spending time caring for elderly relatives. Furthermore, both Baby Boomers and Gen Ys believe flexible work is important and want opportunities to work remotely at least part of the time.27

Compressed Workweeks

Compressed Workweeks

A compressed workweek is any schedule that allows a full-time job to be completed in fewer than the standard five days. The most common form is the “4/40”—40 hours of work accomplished in four 10-hour days, leaving a 3-day break. The additional time off gives workers longer weekends, free weekdays to pursue personal business, and lower commuting costs. In return, the organization hopes for less absenteeism, greater work motivation, and improved recruiting of new employees.28 However, scheduling compressed workweeks can be more complicated, overtime pay for time over 8 hours in one day may be required by law, and union opposition to the longer workday is also a possibility.

A compressed workweek allows a full-time job to be completed in fewer than the standard five days.

Flexible Working Hours

Flexible Working Hours

Another alternative is some form of flexible working hours or flextime that gives individuals daily choice in work hours. A common flex schedule requires certain hours of “core” time but leaves employees free to choose their remaining hours from flexible time blocks. One person, for example, may start early and leave early, whereas another may start later and leave later.

Flexible working hours give individuals some amount of choice in scheduling their daily work hours.

All top 100 companies in Working Mother magazine's list of best employers for working moms offer flexible scheduling. Reports indicate that the flexibility gained to deal with nonwork obligations can lower turnover, absenteeism, and tardiness for the organization while reducing stress and raising commitment and performance by workers.29 Flexible hours help employees manage children's schedules, fulfill elder care responsibilities, and attend to personal affairs such as medical and dental appointments, home emergencies, banking, and so on.

Job Sharing

Job Sharing

In job sharing, two or more persons split one full-time job. This can be done, for example, on a half day, weekly, or monthly basis. Organizations benefit from job sharing when they can attract talented people who would otherwise be unable to work. Some job sharers report less burnout and claim that they feel recharged each time they report for work. The tricky part of this arrangement is finding two people who will stay coordinated and work well with each other.

In job sharing, one full-time job is split between two or more persons who divide the work according to agreed-upon hours.

Job sharing should not be confused with something called work sharing. This occurs when workers agree to cut back on the number of hours they work in order to protect against layoffs. In the recent economic crisis, for example, workers in some organizations agreed to voluntarily reduce their paid hours worked so that others would not lose their jobs.

Work sharing is when employees agree to work fewer hours to avoid layoffs.

Telecommuting

Telecommuting

Technology has enabled yet another alternative work arrangement that is now highly visible in employment sectors ranging from higher education to government, and from manufacturing to services.30 Telecommuting is work done at home or in a remote location via the use of computers, tablets, and smart phone connections with bosses, co-workers, and customers. And it's popular. About four out of five employees say they would like the option and consider it a “significant job perk.”31

Telecommuting is work done at home or from a remote location using computers, tablets, and smart phone devices.

When asked what they like, telecommuters report increased productivity, fewer distractions, the freedom to be their own boss, and the benefit of having more time for themselves. They also like the added flexibility, comforts of home, and being able to live and work in locations consistent with personal lifestyles. Potential negatives are reported as well. Some telecommuters say they end up working too much while having difficulty separating work and personal life. Other complaints include not being considered as important as on-site workers, feeling isolated from co-workers and less identified with the work team, and even having trouble managing interruptions from everyday family affairs. One telecommuter says, “You have to have self-discipline and pride in what you do, but you also have to have a boss that trusts you enough to get out of the way.”32

Employers that allow telecommuting expect it to help improve work-life balance and job satisfaction for employees. But, some also worry that too much telecommuting disrupts schedules and reduces important face-to-face time among co-workers. Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer, for example, was willing to face criticism when she decided to disallow it. Her reasoning was that working from home detracted from Yahool's collaborative culture and ability to innovate.33

CHECKING ETHICS IN OB

Part-Time Work

Part-Time Work

Part-time work is an increasingly prominent and controversial work arrangement. One of the big downsides is that part-timers often fail to qualify for fringe benefits such as health care insurance and retirement plans. In addition, they may be paid less than their full-time counterparts. Because part-timers are easily released and hired as needs dictate, they are also likely to be laid off before full-timers during difficult business times.

The number of part-time workers is growing as today's employers try to stay flexible and manage costs in a demanding global economy. This is reflected in what you might hear called a “permanent temp economy” one where working as a permanent part timer—or—permatemp is a new reality for many job hunters.34 Some choose this schedule voluntarily. Recent data, for example, show that many Millennials are opting for a shifting portfolio of freelance jobs that give them flexibility while still providing earning power.35 But, there's no doubt that part-time work is an involuntary alternative for many who would prefer full-time work but are unable to get it.

6 Study Guide

Key Questions and Answers

What is the link between motivation, performance, and rewards?

- The integrated model of motivation brings together insights from content, process, and learning theories around the basic effort-performance-reward linkage.

- Reward systems emphasize a mix of intrinsic rewards, such as a sense of achievement from completing a challenging task, and extrinsic rewards, such as receiving a pay increase.

- Pay-for-performance systems takes a variety of forms, including merit pay, gain-sharing and profit-sharing plans, stock options, and employee stock ownership.

What are the essentials of performance management?

- Performance management is the process of managing performance measurement and the variety of human resource decisions associated with such measurement.

- Performance measurement serves both an evaluative purpose for reward allocation and a development purpose for future performance improvement.

- Performance measurement can be done using output measures of performance accomplishment or activity measures of performance efforts.

- The ranking, paired comparison, and forced-distribution approaches are examples of comparative performance appraisal methods.

- The graphic rating scale and the behaviorally anchored rating scale use individual ratings on personal and performance characteristics to appraise performance.

- 360° appraisals involve the full circle of contacts a person may have in job performance—from bosses to peers to subordinates to internal and external customers.

- Common performance measurement errors include halo errors, central tendency errors, recency errors, personal bias errors, and cultural bias errors.

How do job designs influence motivation and performance?

- Job design by scientific management or job simplification standardizes work and employs people in clearly defined and specialized tasks.

- Job enlargement increases task variety by combining two or more tasks previously assigned to separate workers; job rotation increases task variety by periodically rotating workers among jobs involving different tasks; job enrichment builds bigger and more responsible jobs by adding planning and evaluating duties.

- The job characteristics model offers a diagnostic approach to job enrichment based on analysis of five core job characteristics: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback.

- The job characteristics model does not assume that everyone wants an enriched job; it indicates that job enrichment will be more successful for persons with high-growth needs, requisite job skills, and context satisfaction.

What are the motivational opportunities of alternative work arrangements?

- The compressed workweek allows a full-time workweek to be completed in fewer than five days, typically offering four ten-hour days of work and three days free.

- Flexible working hours allow employees some daily choice in scheduling core and flex time.

- Job sharing occurs when two or more people divide one full-time job according to agreements among themselves and the employer.

- Telecommuting involves work at home or at a remote location while communicating with the home office as needed via computer and related technologies.

- Part-time work requires less than a forty-hour workweek and can be done on a temporary or permanent schedule.

Terms to Know

360° review (p. 128)

Activity measures (p. 125)

Behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS) (p. 127)

Bonuses (p. 123)

Compressed workweek (p. 134)

Critical incident diaries (p. 127)

Employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) (p. 124)

Employee value proposition (p. 120)

Extrinsic rewards (p. 121)

Flexible working hours (p. 134)

Forced distribution (p. 127)

Gain sharing (p. 123)

Graphic rating scales (p. 127)

Intrinsic rewards (p. 121)

Job design (p. 129)

Job enlargement (p. 130)

Job enrichment (p. 131)

Job rotation (p. 130)

Job sharing (p. 134)

Job simplification (p. 130)

Merit pay (p. 122)

Motivation (p. 120)

Output measures (p. 125)

Paired comparison (p. 127)

Performance-contingent pay (p. 122)

Person-job fit (p. 120)

Person-organization fit (p. 120)

Profit sharing (p. 123)

Ranking (p. 126)

Reliability (p. 126)

Scientific management (p. 129)

Skill-based pay (p. 124)

Stock options (p. 124)

Telecommuting (p. 135)

Validity (p. 126)

Work sharing (p. 134)

Self-Test 6

Multiple Choice

Multiple Choice

- In the integrated model of motivation, what predicts effort?

- (a) rewards

- (b) organizational support

- (c) ability

- (d) motivation

- Pay is generally considered a/an__________ reward, whereas a sense of personal growth experienced from working at a task is an example of a/an________reward.

- (a) extrinsic, skill-based

- (b) skill-based, intrinsic

- (c) extrinsic, intrinsic

- (d) absolute, comparative

- If someone improves productivity by developing a new work process and receives a portion of the productivity savings as a monetary reward, this is an example of a/an________pay plan.

- (a) cost-sharing

- (b) gain-sharing

- (c) ESOP

- (d) stock option

- Performance measurement serves both evaluation and_________purposes.

- (a) reward allocation

- (b) counseling

- (c) discipline

- (d) benefits calculations

- Which form of performance assessment is an example of the comparative approach?

- (a) forced distribution

- (b) graphic rating scale

- (c) BARS

- (d) critical incident diary

- If a performance assessment method fails to accurately measure a person's performance on actual job content, it lacks__________.

- (a) performance contingency

- (b) leniency

- (c) validity

- (d) strictness

- A written record that describes in detail various examples of a person's positive and negative work behaviors is most likely part of which performance appraisal method?

- (a) forced distribution

- (b) critical incident diary

- (c) paired comparison

- (d) graphic rating scale

- When a team leader evaluates the performance of all team members as “average” the possibility for_________error in the performance appraisal is quite high.

- (a) personal bias

- (b) recency

- (c) halo

- (d) central tendency

- Job simplification is closely associated with__________as originally developed by Frederick Taylor.

- (a) vertical loading

- (b) horizontal loading

- (c) scientific management

- (d) self-efficacy

- Job_________increases job_________by combining into one job several tasks of similar difficulty.

- (a) rotation, depth

- (b) enlargement, depth

- (c) rotation, breadth

- (d) enlargement, breadth

- If a manager redesigns a job through vertical loading, she would most likely

- (a) bring tasks from earlier in the workflow into the job

- (b) bring tasks from later in the workflow into the job

- (c) bring higher-level or managerial responsibilities into the job

- (d) raise the standards for high performance

- In the job characteristics model, a person will be most likely to find an enriched job motivating if he or she__________.

- (a) receives stock options

- (b) has ability and support

- (c) is unhappy with job context

- (d) has strong growth needs

- In the job characteristics model,_________indicates the degree to which an individual is able to make decisions affecting his or her work.

- (a) task variety

- (b) task identity

- (c) task significance

- (d) autonomy

- When a job allows a person to do a complete unit of work—for example, process an insurance claim from point of receipt from the customer to the point of final resolution—it would be considered high on which core characteristic?

- (a) task identity

- (b) task significance

- (c) task autonomy

- (d) feedback

- The 4/40 is a type of________work arrangement.

- (a) compressed workweek

- (b) “allow workers to change machine configurations to make different products”

- (c) job-sharing

- (d) permanent part-time

Short Response

Short Response

16. Explain how a 360° review works as a performance appraisal approach.

17. Explain the difference between halo errors and recency errors in performance assessment.

18. What role does growth-need strength play in the job characteristics model?

19. What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of a compressed workweek?

Applications Essay

Applications Essay

20. Choose a student organization on your campus. Discuss in detail how the concepts and ideas in this chapter could be applied in various ways to improve motivation and performance among its members.

Steps to Further Learning 6

Top Choices from The OB Skills Workbook

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook found at the back of the book are suggested for Chapter 6.

“It gets the kid's attention . . . and motivates them to study more.”

“It gets the kid's attention . . . and motivates them to study more.”