TEAM AND EXPERIENTIAL EXERCISES

EXERCISE 1

My Best Manager

Instructions

- Make a list of the attributes that describe the best manager you ever worked for. If you have trouble identifying an actual manager, make a list of attributes you would like the manager in your next job to have.

- Form a group of four or five persons and share your lists.

- Create one list that combines all the unique attributes of the “best” managers represented in your group. Make sure that you have all attributes listed, but list each only once. Place a check mark next to those that were reported by two or more members. Have one of your members prepared to present the list in general class discussion.

- After all groups have finished Step 3, spokespersons should report to the whole class. The instructor will make a running list of the “best” manager attributes as viewed by the class.

- Feel free to ask questions and discuss the results.

EXERCISE 2

Graffiti Needs Assessment: Involving Students in the First Class Session

Contributed by Barbara K. Goza, Visiting Associate Professor, University of California at Santa Cruz, and Associate Professor, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

From Journal of Management Education, 1993.

Instructions

- Complete the following sentences with as many endings as possible.

- When I first came to this class, I thought . . .

- My greatest concern this term is . . .

- In 3 years I will be . . .

- The greatest challenge facing the world today is . . .

- Organizational behavior specialists do . . .

- Human resources are . . .

- Organizational research is . . .

- The most useful question I've been asked is . . .

- The most important phenomenon in organizations is . . .

- I learn the most when . . .

- Your instructor will guide you in a class discussion about your responses. Pay careful attention to similarities and differences among various students' answers.

EXERCISE 3

My Best Job

Procedure

- Make a list of the top five things you expect from your first (or next) full-time job.

- Exchange lists with a nearby partner. Assign probabilities (or odds) to each goal on your partner's list to indicate how likely you feel it is that the goal can be accomplished. (Note: Your instructor may ask that everyone use the same probabilities format.)

- Discuss your evaluations with your partner. Try to delete superficial goals or modify them to become more substantial. Try to restate any unrealistic goals to make them more realistic. Help your partner do the same.

- Form a group of four to six persons. Within the group, have everyone share what they now consider to be the most “realistic” goals on their lists. Elect a spokesperson to share a sample of these items with the entire class.

- Discuss what group members have individually learned from the exercise. Await further class discussion led by your instructor.

EXERCISE 4

What Do You Value in Work?

Instructions

- The following nine items are from a survey conducted by Nicholas J. Beutell and O. C. Brenner (“Sex Differences in Work Values,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 28, pp. 29–41, 1986). Rank the nine items in terms of how important (9 = most important) they would be to you in a job.

How important is it to you to have a job that:

- Is respected by other people?

- Encourages continued development of knowledge and skills?

- Provides job security?

- Provides a feeling of accomplishment?

- Provides the opportunity to earn a high income?

- Is intellectually stimulating?

- Rewards good performance with recognition?

- Provides comfortable working conditions?

- Permits advancement to high administrative responsibility?

- Form into groups as designated by your instructor. Within each group, the men in the group will meet to develop a consensus ranking of the items as they think the women in the Beutell and Brenner survey ranked them. The reasons for the rankings should be shared and discussed so they are clear to everyone. The women in the group should not participate in this ranking task. They should listen to the discussion and be prepared to comment later in class discussion. A spokesperson for the men in the group should share the group's rankings with the class.

- (Optional) Form into groups as designated by your instructor, but with each group consisting entirely of men or women. Each group should meet and decide which of the work values members of the opposite sex ranked first in the Beutell and Brenner survey. Do this again for the work value ranked last. The reasons should be discussed, along with reasons that each of the other values probably was not ranked first—or last. A spokesperson for each group should share group results with the rest of the class.

Source: Adapted from Roy J. Lewicki, Donald D. Bowen, Douglas T. Hall, and Francine S. Hall, Experiences in Management and Organizational Behavior, 3rd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1988), pp. 23–26. Used by permission.

EXERCISE 5

My Asset Base

A business has an asset base or set of resources that it uses to produce a good or service of value to others. For a business, these are the assets or resources it uses to achieve results, including capital, land, patented products or processes, buildings and equipment, raw materials, and the human resources or employees, among others.

Each of us has an asset base that supports our ability to accomplish the things we set out to do. We refer to our personal assets as talents, strengths, or abilities. We probably inherit our talents from our parents, but we acquire many of our abilities and strengths through learning. One thing is certain: We feel very proud of the talents and abilities we have.

Instructions

- Printed here is a T chart that you are to fill out. On the right-hand side of the T, list four or five of your accomplishments—things you have done of which you are most proud. Your accomplishments should only include those things for which you can take credit, those things for which you are primarily responsible. If you are proud of the sorority to which you belong, you may be justifiably proud, but don't list it unless you can argue that the sorority's excellence is due primarily to your efforts. However, if you feel that having been invited to join the sorority is a major accomplishment for you, then you may include it.

When you have completed the right-hand side of the chart, fill in the left-hand side by listing talents, strengths, and abilities that you have that have enabled you to accomplish the outcomes listed on the right-hand side.

My Asset Base

- Share your lists with other team members. As each member shares his or her list, pay close attention to your own perceptions and feelings. Notice the effect this has on your attitudes toward the other team members.

- Discuss these questions in your group:

- How did your attitudes and feelings toward other members of the team change as you pursued the activity? What does this tell you about the process whereby we come to get to know and care about people?

- How did you feel about the instructions the instructor provided? What did you expect to happen? Were your expectations accurate?

Source: Adapted from Donald D. Bowen et al., Experiences in Management and Organizational Behavior, 4th ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997).

EXERCISE 6

Expatriate Assignments

Contributed by Robert E. Ledman, Morehouse College

This exercise focuses on issues related to workers facing international assignments. It illustrates that those workers face a multitude of issues. It further demonstrates that managers who want employees to realize the maximum benefits of international assignments should be aware of, and prepared to deal with, those issues. Some of the topics that are easily addressed with this exercise include the need for culture and language training for the employees and their families and the impact that international assignments may have on an employee's family and how that may affect an employee's willingness to seek such assignments.

Instructions

- Form into “families” of four or five. Since many students today have only one parent at home, it is helpful if some groups do not have students to fill both parental roles in the exercise. Each student is assigned to play a family member and given a description of that person.

- Enter into a 20-minute discussion to explore how a proposed overseas assignment will affect the family members. Your goal is to try to reach a decision about whether the assignment should be taken. You must also decide whether the entire family or only the family member being offered the assignment will relocate. The assignment is for a minimum of two years, with possible annual extensions resulting in a total of four years, and your family, or the member offered the assignment, will be provided, at company expense, one trip back to the states each year for a maximum period of fifteen days. The member offered the assignment will not receive any additional housing or cost-of-living supplements described in the role assignment if he or she chooses to go overseas alone and can expect his or her living expenses to exceed substantially the living allowance being provided by the company. In your discussion, address the following questions:

- What are the most important concerns your family has about relocating to a foreign country?

- What information should you seek about the proposed host country to be able to make a more informed decision?

- What can the member offered the assignment do to make the transition easier if he or she goes overseas alone? If the whole family relocates?

- What should the member offered the assignment do to ensure that this proposed assignment will not create unnecessary stress for him or her and the rest of the family?

- What lessons for managers of expatriate assignees are presented by the situation in this exercise?

Try to reach some “family” consensus. If a consensus is not possible, however, resolve any differences in the manner you think the family in the role descriptions would ultimately resolve any differences.

- Share your answers with the rest of the class. Explain the rationale for your answers and answer questions from the remainder of the class.

- (Optional) After each group has reported on a given question, the instructor may query the class about how their answers are consistent, or inconsistent, with common practices of managers as described in the available literature.

Descriptions of Family Members

Person Being Offered Overseas Assignment

This person is a middle- to upper-level executive who is on a fast track to senior management. He or she has been offered the opportunity to manage an overseas operation, with the assurance of a promotion to a vice presidency upon return to the states. The company will pay all relocation expenses, including selling costs for the family home and the costs associated with finding a new home upon return. The employer will also provide language training for the employee and cultural awareness training for the entire family. The employee will receive a living allowance equal to 20 percent of his or her salary. This should be adequate to provide the family a comparable standard of living to that which is possible on the employee's current salary.

Spouse of the Person Offered an Overseas Assignment (Optional)

This person is also a professional with highly transferable skills and experience for the domestic market. It is unknown how easily he or she may be able to find employment in the foreign country. This person's income, though less than his or her spouse's, is necessary if the couple is to continue paying for their child's college tuition and to prepare for the next child to enter college in two years. This person has spent fifteen years developing a career, including completing a degree at night.

Oldest Child

This child is a second-semester junior in college and is on track to graduate in 16 months. Transferring at this time would probably mean adding at least one semester to complete the degree. He or she has been dating the same person for over a year; they have talked about getting married immediately after graduation, although they are not yet formally engaged.

Middle Child

This child is a junior in high school. He or she has already begun visiting college campuses in preparation for applying in the fall. This child is involved in a number of school activities; he or she is a photographer for the yearbook and plays a varsity sport. This child has a learning disability for which services are being provided by the school system.

Youngest Child

This child is a middle school student, age 13. He or she is actively involved in Scouting and takes piano lessons. This child has a history of medical conditions that have required regular visits to the family physician and specialists. This child has several very close friends who have attended the same school for several years.

Source: Robert E. Ledman, Gannon University. Presented in the Experiential Exercise Track of the 1996 ABSEL Conference and published in the Proceedings of that conference.

EXERCISE 7

Cultural Cues

Contributed by Susan Rawson Zacur and W. Alan Randolph, University of Baltimore

Introduction

In the business context, culture involves shared beliefs and expectations that govern the behavior of people. In this exercise, foreign culture refers to a set of beliefs and expectations different from those of the participant's home culture (which has been invented by the participants).

Instructions

- (10–15 minutes) Divide into two groups, each with color-coded badges. For example, the blue group could receive blue Sticky notes and the yellow group could receive yellow Sticky notes. Print your first name in bold letters on the badge and wear it throughout the exercise.

Work with your group members to invent your own cultural cues. Think about the kinds of behaviors and words that will signify to all members that they belong together in one culture. For each of the following categories, identify and record at least one important attribute for your culture.

Once you have identified desirable cultural aspects for your group, practice them. It is best to stand with your group and to engage one another in conversations involving two or three people at a time. Your aim in talking with one another is to learn as much as possible about each other—hobbies, interests, where you live, what your family is like, what courses you are taking, and so on, all the while practicing the behaviors and words on the previous page. It is not necessary for participants to answer questions of a personal nature truthfully. Invention is permissible because the conversation is only a means to the end of cultural observation. Your aim at this point is to become comfortable with the indicators of your particular culture. Practice until the indicators are second nature to you.

- Now assume that you work for a business that has decided to explore the potential for doing business with companies in a different culture. You are to learn as much as possible about another culture. To do so, you will send from one to three representatives from your group on a “business trip” to the other culture. These representatives must, insofar as possible, behave in a manner that is consistent with your culture. At the same time, each representative must endeavor to learn as much as possible about the people in the other culture, while keeping eyes and ears open to cultural attributes that will be useful in future negotiations with foreign businesses. (Note: At no time will it be considered ethical behavior for the representative to ask direct questions about the foreign culture's attributes. These must be gleaned from firsthand experience.)

While your representatives are away, you will receive one or more exchange visitors from the other culture, who will engage in conversation as they attempt to learn more about your organizational culture. You must strictly adhere to the cultural aspects of your own culture while you converse with the visitors.

- (5–10 minutes) All travelers return to your home cultures. As a group, discuss and record what you have learned about the foreign culture based on the exchange of visitors. This information will serve as the basis for orienting the next representatives who will make a business trip.

- (5–10 minutes) Select one to three different group members to make another trip to the other culture to check out the assumptions your group has made about the other culture. This “checking out” process will consist of actually practicing the other culture's cues to see whether they work.

- (5–10 minutes) Once the traveler(s) have returned and reported on findings, as a group prepare to report to the class what you have learned about the other culture.

Source: Adapted by Susan Rawson Zacur and W. Alan Randolph from Journal of Management Education, 17:4 (November 1993), pp. 510–516.

EXERCISE 8

Prejudice in Our Lives

Contributed by Susan Schor of Pace University and Annie McKee of The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, with the assistance of Ariel Fishman of The Wharton School

Instructions

- As a large class group, generate a list of groups that tend to be targets of prejudice and stereotypes in our culture—such groups can be based on gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, region, religion, and so on. After generating a list, either as a class or in small groups, identify a few common positive and negative stereotypes associated with each group. Also consider relationships or patterns that exist among some of the lists. Discuss the implications for groups that have stereotypes that are valued in organizations versus groups whose stereotypes are viewed negatively in organizations.

- As an individual, think about the lists you have now generated, and list those groups with which you identify. Write about an experience in which you were stereotyped as a member of a group. Ask yourself the following questions and write down your thoughts:

- What group do I identify with?

- What was the stereotype?

- What happened? When and where did the incident occur? Who said what to whom?

- What were my reactions? How did I feel? What did I think? What did I do?

- What were the consequences? How did the incident affect myself and others?

- Now, in small groups, discuss your experiences. Briefly describe the incident and focus on how the incident made you feel. Select one incident from the ones shared in your group to role-play for the class. Then, as a class, discuss your reactions to each role-play. Identify the prejudice or stereotype portrayed, the feelings the situation evoked, and the consequences that might result from such a situation.

- Think about the prejudices and stereotypes you hold about other people. Ask yourself, “What groups do I feel prejudice toward? What stereotypes do I hold about members of each of these groups?” How may such a prejudice have developed—did a family member or close friend or television influence you to stereotype a particular group in a certain way?

- Now try to identify implications of prejudice in the workplace. How do prejudice and stereotypes affect workers, managers, relationships between people, and the organization as a whole? Consider how you might want to change erroneous beliefs as well as how you would encourage other people to change their own erroneous beliefs.

EXERCISE 9

How We View Differences

Contributed by Barbara Walker

Introduction

Clearly, the workplace of the future will be much more diverse than it is today: more women, more people of color, more international representation, more diverse lifestyles and ability profiles, and the like. Managing a diverse workforce and working across a range of differences is quickly becoming a “core competency” for effective managers.

Furthermore, it is also becoming clear that diversity in a work team can significantly enhance the creativity and quality of the team's output. In today's turbulent business environment, utilizing employee diversity will give the manager and the organization a competitive edge in tapping all of the available human resources more effectively. This exercise is an initial step in the examination of how we work with people whom we perceive as different from us. It is fairly simple, straight-forward, and safe, but its implications are profound.

Instructions

- Read the following:

Imagine that you are traveling in a rental car in a city you have never visited before. You have a one-hour drive on an uncrowded highway before you reach your destination. You decide that you would like to spend the time listening to some of your favorite kind of music on the car radio.

The rental car has four selection buttons available, each with a preset station that plays a different type of music. One plays country music, one plays rock, one plays classical, and one plays jazz. Which type of music would you choose to listen to for the next hour as you drive along? (Assume you want to relax and just stick with one station; you don't want to bother switching around between stations.)

- Form into groups based on the type of music that you have chosen. All who have chosen country will meet in an area designated by the instructor. Those who chose rock will meet in another area, and so on. In your groups, answer the following question. Appoint one member to be the spokesperson to report your answers back to the total group.

Question

For each of the other groups, what words would you use to describe people who like to listen to that type of music?

3. Have each spokesperson report the responses of her or his group to the question in step 2.

Follow with class discussion of these additional questions:

- What do you think is the purpose or value of this exercise?

- What did you notice about the words used to describe the other groups? Were there any surprises in this exercise for you?

- Upon what sorts of data do you think these images were based?

- What term do we normally use to describe these generalized perceptions of another group?

- What could some of the consequences be?

- How do the perceptual processes here relate to other kinds of intergroup differences, such as race, gender, culture, ability, ethnicity, health, age, nationality, and so on?

- What does this exercise suggest about the ease with which intergroup stereotypes form?

- What might be ways an organization might facilitate the valuing and utilizing of differences between people?

Source: Exercise developed by Barbara Walker, a pioneer on work on valuing differences. Adapted for this volume by Douglas T. Hall. Used by permission of Barbara Walker.

EXERCISE 10

Alligator River Story

The Alligator River Story

There lived a woman named Abigail who was in love with a man named Gregory. Gregory lived on the shore of a river. Abigail lived on the opposite shore of the same river. The river that separated the two lovers was teeming with dangerous alligators. Abigail wanted to cross the river to be with Gregory. Unfortunately, the bridge had been washed out by a heavy flood the previous week. So she went to ask Sinbad, a riverboat captain, to take her across. He said he would be glad to if she would consent to go to bed with him prior to the voyage. She promptly refused and went to a friend named Ivan to explain her plight. Ivan did not want to get involved at all in the situation. Abigail felt her only alternative was to accept Sinbad's terms. Sinbad fulfilled his promise to Abigail and delivered her into the arms of Gregory. When Abigail told Gregory about her amorous escapade in order to cross the river, Gregory cast her aside with disdain. Heartsick and rejected, Abigail turned to Slug with her tail of woe. Slug, feeling compassion for Abigail, sought out Gregory and beat him brutally. Abigail was overjoyed at the sight of Gregory getting his due. As the sun set on the horizon, people heard Abigail laughing at Gregory.

Instructions

- Read “The Alligator River Story.”

- After reading the story, rank the five characters in the story beginning with the one whom you consider the most offensive and end with the one whom you consider the least objectionable. That is, the character who seems to be the most reprehensible to you should be entered first in the list following the story, then the second most reprehensible, and so on, with the least reprehensible or objectionable being entered fifth. Of course, you will have your own reasons as to why you rank them in the order that you do. Very briefly note these too.

- Form groups as assigned by your instructor (at least four persons per group with gender mixed).

- Each group should:

- Elect a spokesperson for the group

- Compare how the group members have ranked the characters

- Examine the reasons used by each of the members for their rankings

- Seek consensus on a final group ranking

- Following your group discussions, you will be asked to share your outcomes and reasons for agreement or nonagreement. A general class discussion will then be held.

Source: From Sidney B. Simon, Howard Kirschenbaum, and Leland Howe, Values Clarification, The Handbook, rev. ed. (Sutherland, MA: Values Press, 1991).

EXERCISE 11

Teamwork and Motivation

Contributed by Dr. Barbara McCain, Oklahoma City University

Instructions

1. Read the following situation:

You are the owner of a small manufacturing corporation. Your company manufactures widgets—a commodity. Your widget is a clone of nationally known widgets. Your widget, WooWoo, is less expensive and more readily available than the nationally known brand. Presently, the sales are high. However, there are many rejects, which increases your cost and delays the delivery. You have 50 employees in the following departments: sales, assembly, technology, and administration.

2. In groups, discuss methods to motivate all of the employees in the organization—rank them in terms of preference.

3. Design an organization motivation plan that encourages high job satisfaction, low turnover, high productivity, and high-quality work.

4. Is there anything special you can do about the minimum-wage service worker? How do you motivate this individual? On what motivation theory do you base your decision?

5. Report to the class your motivation plan. Record your ideas on the board and allow all groups to build on the first plan. Discuss additions and corrections as the discussion proceeds.

Worksheet

Directions: Fill in the right-hand column with descriptive terms. These terms should suggest a change in behavior from individual work to teamwork.

EXERCISE 12

The Downside of Punishment

Contributed by Dr. Barbara McCain, Oklahoma City University

Instructions

There are numerous problems associated with using punishment or discipline to change behavior. Punishment creates negative effects in the workplace. To better understand this, work in your group to give an example of each of the following situations:

- Punishment may not be applied to the person whose behavior you want to change.

- Punishment applied over time may suppress the occurrence of socially desirable behaviors.

- Punishment creates a dislike of the person who is implementing the punishment.

- Punishment results in undesirable emotions such as anxiety and aggressiveness.

- Punishment increases the desire to avoid punishment.

- Punishing one behavior does not guarantee that the desired behavior will occur.

- Punishment follow-up requires allocation of additional resources.

- Punishment may create a communication barrier and inhibit the flow of information.

Source: Adapted from class notes: Dr. Larry Michaelson, Oklahoma University.

EXERCISE 13

Tinkertoys

Contributed by Bonnie McNeely, Murray State University

Materials Needed

Tinkertoy sets.

Instructions

- Form groups as assigned by the instructor. The mission of each group or temporary organization is to build the tallest possible Tinkertoy tower. Each group should determine worker roles: at least four students will be builders, some will be consultants who offer suggestions, and the remaining students will be observers who remain silent and complete the observation sheet provided below.

- Rules for the exercise:

- 15 minutes allowed to plan the tower, but only 60 seconds to build.

- No more than two Tinkertoy pieces can be put together during the planning.

- All pieces must be put back in the box before the competition begins.

- Completed tower must stand alone.

Observation Sheet

- What planning activities were observed?

Did the group members adhere to the rules?

- What organizing activities were observed?

Was the task divided into subtasks? Division of labor?

- Was the group motivated to succeed? Why or why not?

- Were any control techniques observed?

Was a timekeeper assigned?

Were backup plans discussed?

- Did a clear leader emerge from the group?

What behaviors indicated that this person was the leader?

How did the leader establish credibility with the group?

- Did any conflicts within the group appear?

Was there a power struggle for the leadership position?

Source: Adapted from Bonnie McNeely, “Using the Tinkertoy Exercise to Teach the Four Functions of Management,” Journal of Management Education, 18: 4 (November 1994), pp. 468–472.

EXERCISE 14

Job Design Preferences

Instructions

- Use the left column to rank the following job characteristics in the order most important to you (1—highest to 10—lowest). Then use the right column to rank them in the order you think they are most important to others.

____ Variety of tasks ____ ____ Performance feedback ____ ____ Autonomy/freedom in work ____ ____ Working on a team ____ ____ Having responsibility ____ ____ Making friends on the job ____ ____ Doing all of a job, not part ____ ____ Importance of job to others ____ ____ Having resources to do well ____ ____ Flexible work schedule ____ - Form workgroups as assigned by your instructor. Share your rankings with other group members. Discuss where you have different individual preferences and where your impressions differ from the preferences of others. Are there any major patterns in your group—for either the “personal” or the “other” rankings? Develop group consensus rankings for each column. Designate a spokesperson to share the group rankings and results of any discussion with the rest of the class.

EXERCISE 15

My Fantasy Job

Contributed by Lady Hanson, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

Instructions

- Think about a possible job that represents what you consider to be your ideal or “fantasy” job. For discussion purposes, try to envision it as a job you would hold within a year of finishing your current studies. Write down a brief description of that job in the following space below. Start the description with the following words: My fantasy job would be . . .

- Review the description of the Hackman/Oldham model of Job Characteristics Theory offered in the textbook. Note in particular the descriptions of the core characteristics. Consider how each of them could be maximized in your fantasy job. Indicate in the spaces that follow how specific parts of your fantasy job will fit into or relate to each of the core characteristics.

- Skill variety: _____________________________________________________________

- Task identity: ____________________________________________________________

- Task significance: _________________________________________________________

- Autonomy: ______________________________________________________________

- Job feedback: ____________________________________________________________

- Form into groups as assigned by your instructor. In the group have each person share his or her fantasy job and the descriptions of its core characteristics. Select one person from your group to tell the class as a whole about her or his fantasy job. Be prepared to participate in a general discussion regarding the core characteristics and how they may or may not relate to job performance and job satisfaction. Consider also the likelihood that the fantasy jobs of class members are really attainable—in other words, Can “fantasy” become fact?

EXERCISE 16

Motivation by Job Enrichment

Contributed by Diana Page, University of West Florida

Instructions

- Form groups of five to seven members. Each group is assigned one of the following categories:

- Bank teller

- Retail sales clerk

- Manager, fast-food service (e.g., McDonald's)

- Wait person

- Receptionist

- Restaurant manager

- Clerical worker (or bookkeeper)

- Janitor

- As a group, develop a short description of job duties for the job your group has been assigned. The list should contain approximately four to six items.

- Next, using job characteristics theory, enrich the job using the specific elements described in the theory. Develop a new list of job duties that incorporate any or all of the core job characteristics suggested by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham, such as skill variety, task identity, and so on. Indicate for each of the new job duties which job characteristic(s) was/were used.

- One member of each group should act as the spokesperson and will present the group's ideas to the class. Specifically describe one or two of the old job tasks. Describe the modified job tasks. Finally, relate the new job tasks the group has developed to specific job core characteristics such as skill variety, skill identity, and so on.

- The group should also be prepared to discuss these and other follow-up questions:

- How would a manager go about enlarging but not enriching this job?

- Why was this job easy or hard?

- What are the possible constraints on actually accomplishing this enrichment in the workplace?

- What possible reasons are there that a worker would not like to have this newly enriched job?

EXERCISE 17

Annual Pay Raises

Instructions

- Read the following job descriptions and decide on a percentage pay increase for each of the eight employees.

- Make salary increase recommendations for each of the eight managers that you supervise. There are no formal company restrictions on the size of raises you give, but the total for everyone should not exceed the $10,900 (a 4 percent increase in the salary pool) that has been budgeted for this purpose. You have a variety of information on which to base the decisions, including a “productivity index” (PI), which Industrial Engineering computes as a quantitative measure of operating efficiency for each manager's work unit. This index ranges from a high of 10 to a low of 1. Indicate the percentage increase you would give each manager in the blank space next to each manager's name. Be prepared to explain why.

- A. Alvarez Alvarez is new this year and has a tough workgroup whose task is dirty and difficult. This is a hard position to fill, but you don't feel Alvarez is particularly good. The word around is that the other managers agree with you. PI = 3. Salary = $33,000.

- B. J. Cook Cook is single and a “swinger” who enjoys leisure time. Everyone laughs at the problems Cook has getting the work out, and you feel it certainly is lacking. Cook has been in the job two years. PI = 3. Salary = $34,500.

- Z. Davis In the position three years, Davis is one of your best people, even though some of the other managers don't agree. With a spouse who is independently wealthy, Davis doesn't need money but likes to work. PI = 7. Salary = $36,600.

- M. Frame Frame has personal problems and is hurting financially. Others gossip about Frame's performance, but you are quite satisfied with this second-year employee. PI = 7. Salary = $34,700.

- C. M. Liu Liu is just finishing a fine first year in a tough job. Highly respected by the others, Liu has a job offer in another company at a 15 percent increase in salary. You are impressed, and the word is that the money is important. PI = 9. Salary = $34,000.

- B. Ratin Ratin is a first-year manager whom you and the others think is doing a good job. This is a bit surprising since Ratin turned out to be a “free spirit” who doesn't seem to care much about money or status. PI = 9. Salary = $33,800.

- H. Smith Smith is a first-year manager recently divorced and with two children to support as a single parent. The others like Smith a lot, but your evaluation is not very high. Smith could certainly use extra money. PI = 5. Salary = $33,000.

- G. White White is a big spender who always has the latest clothes and a new car. In the first year on what you would call an easy job, White doesn't seem to be doing very well. For some reason, though, the others talk about White as the “cream of the new crop.” PI = 5. Salary = $33,000.

- Convene in a group of four to seven persons and share your raise decisions.

- As a group, decide on a new set of raises and be prepared to report them to the rest of the class. Make sure that the group spokesperson can provide the rationale for each person's raise.

- The instructor will call on each group to report its raise decisions. After discussion, an “expert's” decision will be given.

EXERCISE 18

Serving on the Boundary

Contributed by Joseph A. Raelin, Boston College

Instructions

The objective of this exercise is to experience what it is like being on the boundary of your team or organization and to experience the boundary person's divided loyalties.

- As a full class, decide on a stake you are willing to wager on this exercise. Perhaps it will be 5 cents or 10 cents per person, or even more.

- Form into teams. Select or elect one member from your team to be an expert. The expert will be the person most competent in the field of international geography.

- The experts will then form into a team of their own.

- The teams, including the expert team, are going to be given a straightforward question to work on. Whichever team comes closest to deriving the correct answer will win the pool from the stakes already collected. The question is any one of the following as assigned by the instructor: (a) What is the airline distance between Beijing and Moscow (in miles)? (b) What is the highest point in Texas (in feet)? (c) What was the number of American battle deaths in the Revolutionary War?

- Each team should now work on the question, including the expert team. However, after all the teams come up with a verdict, the experts will be allowed to return to their “home” team to inform the team of the expert team's deliberations.

- The expert team members are now asked to reconvene as an expert team. They should determine their final answer to the question. Then they are to face a decision. The instructor will announce that for a period of up to two minutes, any expert may either return to their home team (to sink or swim with the answer of the home team) or remain with the expert team. As long as two members remain in the expert team, it will be considered a group and may vie for the pool. Home teams, during the two-minute decision period, can do whatever they would like to do—within bounds of normal decorum—to try to persuade their expert member to return.

- After the two minutes are up, teams will hand in their responses to the question, and the team with the closest answer (up or down) will be awarded the pool.

- Class members should be prepared to discuss the following questions:

- What did it feel like to be a boundary person (the expert)?

- What could the teams have done to corral any of the boundary persons who chose not to return home?

EXERCISE 19

Eggsperiential Exercise

Contributed by Dr. Barbara McCain, Oklahoma City University

Materials Needed

Chairs

1 raw egg per group

6 plastic straws per group

Instructions

- Form into equal groups of five to seven people.

- The task is to drop an egg from the chair onto the plastic without breaking the egg. Groups can evaluate the materials and plan their task for 10 minutes. During this period the materials may not be handled.

- Groups have 10 minutes for construction.

- One group member will drop the egg while standing on top of a chair in front of the class. One by one, a representative from each group will drop his or her group's eggs.

- Optional: Each group will name their egg.

- Each group discusses their individual/group behaviors during this activity.

1 yard of plastic tape

1 large plastic jar

Optional: This analysis may be summarized in written form. The following questions may be utilized in the analysis:

- What kind of group is it? Explain.

- Was the group cohesive? Explain.

- How did the cohesiveness relate to performance? Explain.

- Was there evidence of groupthink? Explain.

- Were group norms established? Explain.

- Was there evidence of conflict? Explain.

- Was there any evidence of social loafing? Explain.

EXERCISE 20

Scavenger Hunt-Team Building

Contributed by Michael R. Manning and Paula J. Schmidt, New Mexico State University

Introduction

Think about what it means to be part of a team—a successful team. What makes one team more successful than another? What does each team member need to do in order for their team to be successful? What are the characteristics of an effective team?

Instructions

- Form teams as assigned by your instructor. Locate the listed items while following these important rules:

- Your team must stay together at all times—that is, you cannot go in separate directions.

- Your team must return to the classroom within the time allotted by the instructor.

The team with the most items on the list will be declared the most successful team.

- Next, reflect on your team's experience. What did each team member do? What was your team's strategy? What made your team effective? Make a list of the most important things your team did to be successful. Nominate a spokesperson to summarize your team's discussion for the class. What items were similar between teams? That is, what helped each team to be effective?

Items for Scavenger Hunt

Each item is to be identified and brought back to the classroom.

- A book with the word Team in the title.

- A joke about teams that you share with the class.

- A blade of grass from the university football field.

- A souvenir from the state.

- A picture of a team or group.

- A newspaper article about a team.

- A team song to be composed and performed for the class.

- A leaf from an oak tree.

- Stationery from the dean's office.

- A cup of sand.

- A pine cone.

- A live reptile. (Note: Sometimes a team member has one for a pet or the students are ingenious enough to visit a local pet store.)

- A definition of group “cohesion” that you share with the class.

- A set of chopsticks.

- Three cans of vegetables.

- A branch of an elm tree.

- Three unusual items.

- A ball of cotton.

- The ear from a prickly pear cactus.

- A group name.

(Note: Items may be substituted as appropriate for your locale.)

Source: Adapted from Michael R. Manning and Paula J. Schmidt, Journal of Management Education, “Building Effective Work Teams: A Quick Exercise Based on a Scavenger Hunt' (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995), pp. 392–398. Used by permission. Reference for list of items for scavenger hunt from C. E. Larson and F. M. Lafas, Team Work: What Must Go Right/What Can Go Wrong (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1989).

EXERCISE 21

Work Team Dynamics

Introduction

Think about your course work team, a work team you are involved in for another course, or any other team suggested by the instructor. Indicate how often each of the following statements accurately reflects your experience in the team. Use this scale:

1 = Always 2 = Frequently 3 = Sometimes 4 = Never

- 1. My ideas get a fair hearing.

- 2. I am encouraged for innovative ideas and risk taking.

- 3. Diverse opinions within the team are encouraged.

- 4. I have all the responsibility I want.

- 5. There is a lot of favoritism shown in the team.

- 6. Members trust one another to do their assigned work.

- 7. The team sets high standards of performance excellence.

- 8. People share and change jobs a lot in the team.

- 9. You can make mistakes and learn from them on this team.

- 10. This team has good operating rules.

Instructions

Form groups as assigned by your instructor. Ideally, this will be the team you have just rated. Have all team members share their ratings, and make one master rating for the team as a whole. Circle the items on which there are the biggest differences of opinion. Discuss those items and try to find out why they exist. In general, the better a team scores on this instrument, the higher its creative potential. If everyone has rated the same team, make a list of the five most important things members can do to improve its operations in the future. Nominate a spokesperson to summarize the team discussion for the class as a whole.

Source: Adapted from William Dyer, Team Building, 2nd ed. (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987), pp. 123–125.

EXERCISE 22

Identifying Team Norms

Instructions

- Choose an organization you know quite a bit about.

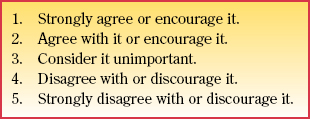

- Complete the following questionnaire, indicating your responses using one of the following:

If an employee in this organization were to ________, most other employees would:

| 1. show genuine concern for the problems that face the organization and make suggestions about solving them | ____ |

| 2. set very high personal standards of performance | ____ |

| 3. try to make the workgroup operate more like a team when dealing with issues or problems | ____ |

| 4. think of going to a supervisor with a problem | ____ |

| 5. evaluate expenditures in terms of the benefits they will provide for the organization | ____ |

| 6. express concern for the well-being of other members of the organization | ____ |

| 7. keep a customer or client waiting while looking after matters of personal convenience | ____ |

| 8. criticize a fellow employee who is trying to improve things in the work situation | ____ |

| 9. actively look for ways to expand his or her knowledge to be able to do a better job | ____ |

| 10. be perfectly honest in answering this questionnaire | ____ |

Scoring

A = +2, B = +1, C = 0, D = −1, E = −2

- Organizational/Personal Pride

Score _____

- Performance/Excellence

Score _____

- Teamwork/Communication

Score _____

- Leadership/Supervision

Score _____

- Profitability/Cost-Effectiveness

Score _____

- Colleague/Associate Relations

Score _____

- Customer/Client Relations

Score _____

- Innovativeness/Creativity

Score _____

- Training/Development

Score _____

- Candor/Openness

Score _____

EXERCISE 23

Work Team Culture

Contributed by Conrad N. Jackson, MPC Inc.

Instructions

The bipolar scales on this instrument can be used to evaluate a group's process in a number of useful ways. Use it to measure where you see the group to be at present. To do this, circle the number that best represents how you see the culture of the group. You can also indicate how you think the group should function by using a different symbol, such as an asterisk (**), to indicate how you saw the group at some time in the past.

- If you are assessing your own group, have everyone fill in the instrument, summarize the scores, then discuss their bases (what members say and do that has led to these interpretations) and implications. This is often an extremely productive intervention to improve group or team functioning.

- If you are assessing another group, use the scores as the basis for your feedback. Be sure to provide specific feedback on behavior you have observed in addition to the subjective interpretations of your ratings on the scales in this instrument.

- The instrument can also be used to compare a group's self-assessment with the assessment provided by another group.

Source: Adapted from Donald D. Bowen et al., Experiences in Management and Organizational Behavior, 4th ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997.)

EXERCISE 24

The Hot Seat

Contributed by Barry R. Armandi, SUNY-Old Westbury

Instructions

1. Form into groups as assigned by your instructor.

2. Read the following situation.

A number of years ago, Professor Stevens was asked to attend a departmental meeting at a university. He had been on leave from the department, but a junior faculty member discreetly requested that he attend to protect the rights of the junior faculty. The Chair, or head of the department, was a typical Machiavellian, whose only concerns were self-serving. Professor Stevens had had a number of previous disagreements with the Chair. The heart of the disagreements centered around the Chair's abrupt and domineering style and his poor relations with the junior faculty, many of whom felt mistreated and scared.

The department was a conglomeration of different professorial types. Included in the mix were behavioralists, generalists, computer scientists, and quantitative analysts. The department was embedded in the school of business, which included three other departments. There was much confusion and concern among the faculty, since this was a new organizational design. Many of the faculty were at odds with each other over the direction the school was now taking.

At the meeting, a number of proposals were to be presented that would seriously affect the performance and future of certain junior faculty, particularly those who were behavioral scientists. The Chair, a computer scientist, disliked the behaviorists, who he felt were “always analyzing the motives of people.” Professor Stevens, who was a tenured full professor and a behaviorist, had an objective to protect the interests of the junior faculty and to counter the efforts of the Chair.

Including Professor Stevens, there were nine faculty present. The following diagram shows the seating arrangement and the layout of the room. The ×s signify those faculty who were allies of the Chair. The +s are those opposed to the Chair and supportive of Professor Stevens, and the ?s were undecided and could be swayed either way. The circled numbers represent empty seats. Both ?s were behavioralists, and the + next to them was a quantitative analyst. Near the door, the first × was a generalist, the two +s were behavioralists, and the second × was a quantitative analyst. The diagram shows the seating of everyone but Professor Stevens, who was the last one to enter the room. Standing at the door, Professor Stevens surveyed the room and within 10 seconds knew which seat was the most effective to achieve his objective.

3. Answer the following questions in your group:

- Which seat did Professor Stevens select and why?

- What is the likely pattern of communication and interaction in this group?

- What can be done to get this group to work harmoniously?

EXERCISE 25

Interview a Leader

Contributed by Bonnie McNeely, Murray State University

Instructions

- Make an appointment to interview a leader. It can be a leader working in a business or nonprofit organization, such as a government agency, school, and so on. Base the interview on the form provided here, but feel free to add your own questions.

- Bring the results of your interview to class. Form into groups as assigned by your instructor. Share the responses from your interview with your group and compare answers. What issues were similar? Different? Were the stress levels of leaders working in nonprofit organizations as high as those working in for-profit firms? Were you surprised at the number of hours per week worked by leaders?

- Be prepared to summarize the interviews done by your group as a formal written report if asked to do so by the instructor.

Interview Questionnaire

Student's Name ____ Date ____

- Position in the organization (title):

- Number of years in current position:

Number of years of managerial experience:

- Number of people directly supervised:

- Average number of hours worked a week:

- How did you get into leadership?

- What is the most rewarding part of being a leader?

- What is the most difficult part of your job?

- What would you say are the keys to success for leaders?

- What advice do you have for an aspiring leader?

- What type of ethical issues have you faced as a leader?

- If you were to enroll in a leadership seminar, what topics or issues would you want to learn more about?

- (Student question)

Gender: M _____ F _____ Years of formal education _____

Level of job stress: Very high _____ High _____ Average _____ Low _____

Profit organization _____ Nonprofit organization _____

Additional information/Comments:

Source: Adapted from Bonnie McNeely, “Make Your Principles of Management Class Come Alive, Journal of Management Education, 18:2 (May 1994), pp. 246–249.

EXERCISE 26

Leadership Skills Inventories

Instructions

- Look over the following skills and ask your instructor to clarify those you do not understand.

- Complete each category by checking either the “Strong” or “Needs Development” category in relation to your own level with each skill.

- After completing each category, briefly describe a situation in which each of the listed skills has been utilized.

- Meet in your groups to share and discuss inventories. Prepare a report summarizing major development needs in your group.

Instrument

EXERCISE 27

Leadership and Participation in Decision Making

Instructions

- For the ten situations described here, decide which of the three styles you would use for that unique situation. Place the letter A, P, or L on the line before each situation's number.

A—authority; make the decision alone without additional inputs.

P—consultative; make the decision based on group inputs.

L—group; allow the group to which you belong to make the decision.

Decision Situations

- i. You have developed a new work procedure that will increase productivity. Your boss likes the idea and wants you to try it within a few weeks. You view your employees as fairly capable and believe that they will be receptive to the change.

- ii. The industry of your product has new competition. Your organization's revenues have been dropping. You have been told to lay off three of your ten employees in two weeks. You have been the supervisor for over one year. Normally, your employees are very capable.

- iii. Your department has been facing a problem for several months. Many solutions have been tried and have failed. You finally thought of a solution, but you are not sure of the possible consequences of the change required or its acceptance by the highly capable employees.

- iv. Flextime has become popular in your organization. Some departments let each employee start and end work whenever they choose. However, because of the cooperative effort of your employees, they must all work the same eight hours. You are not sure of the level of interest in changing the hours. Your employees are a very capable group and like to make decisions.

- v. The technology in your industry is changing faster than the members of your organization can keep up. Top management hired a consultant who has given the recommended decision. You have two weeks to make your decision. Your employees are capable, and they enjoy participating in the decision-making process.

- vi. Your boss called you on the telephone to tell you that someone has requested an order for your department's product with a very short delivery date. She asked that you call her back in 15 minutes with the decision about taking the order. Looking over the work schedule, you realize that it will be very difficult to deliver the order on time. Your employees will have to push hard to make it. They are cooperative, capable, and enjoy being involved in decision making.

- vii. A change has been handed down from top management. How you implement it is your decision. The change takes effect in one month. It will personally affect everyone in your department. The acceptance of the department members is critical to the success of the change. Your employees are usually not too interested in being involved in making decisions.

- viii. You believe that productivity in your department could be increased. You have thought of some ways that may work, but you're not sure of them. Your employees are very experienced; almost all of them have been in the department longer than you have.

- ix. Top management has decided to make a change that will affect all of your employees. You know that they will be upset because it will cause them hardship. One or two may even quit. The change goes into effect in thirty days. Your employees are very capable.

- x. A customer has offered you a contract for your product with a quick delivery date. The offer is open for two days. Meeting the contract deadline would require employees to work nights and weekends for six weeks. You cannot require them to work overtime. Filling this profitable contract could help get you the raise you want and feel you deserve. However, if you take the contract and don't deliver on time, it will hurt your chances of getting a big raise. Your employees are very capable.

- Form groups as assigned by your instructor. Share and compare your choices for each decision situation. Reconcile any differences and be prepared to defend your decision preferences in general class discussion.

EXERCISE 28

My Best Manager: Revisited

Contributed by J. Marcus Maier, Chapman University

Instructions

- Refer to the list of qualities—or profiles—the class generated earlier in the course for the “Best Manager.”

- Looking first at your Typical Managers profile, suppose you took this list to 100 average people on the street (or at the local mall) and asked them whether ____ (Trait X, Quality Y) was “more typical of men or of women in our culture.” What do you think most of them would say? That ____ (X, Y etc.) is more typical of women? or of men? or of neither/both?1 Do this for every trait on your list(s). (5 min.)

- Now do the same for the qualities we generated in our Best Manager profile. (5 min.)

- A straw vote is taken, one quality at a time, to determine the class's overall gender identification of each trait, focusing on the Typical Managers profile (10–15 min.). Then this is repeated for the Best Manager profile (10–15 min.).2

- Discussion. What do you see in the data this group has generated? How might you interpret these results? (15–20 min.)

Source: Based on J. Marcus Maier, “The Gender Prism,” Journal of Management Education 17(3), pp. 285–314. 1994 Fritz Roethlisberger Award Recipient for Best Paper (Updated, 1996).

1This gets the participants to move outside of their own conceptions to their awareness of societal definitions of masculinity and femininity.

2This is done by a rapid show of hands, looking for a clear majority vote. An “f” (for “feminine”) is placed next to those qualities that a clear majority indicate are more typical of women, and an “m” (for “masculine”) is placed next to those qualities a clear majority indicate would be more typical of men. (This procedure parallels the median-split method used in determining Bem Sex Role Inventory classifications.) If no clear majority emerges (i.e., if the vote is close), the trait or quality is classified as “both” (f/m). The designations “masculine” or “feminine” are used (rather than “men” or “women”) to underscore the socially constructed nature of each dimension.

EXERCISE 29

Active Listening

Contributed by Robert Ledman, Morehouse College

Instructions

- Review active listening skills and behaviors as described in the textbook and in class.

- Form into groups of three. Each group will have a listener, a talker, and an observer (if the number of students is not evenly divisible by three, two observers are used for one or two groups).

- The “talkers” should talk about any subject they wish, but only if they are being actively listened to. Talkers should stop speaking as soon as they sense active listening has stopped.

- The “listeners” should use a list of active listening skills and behaviors as their guide, and practice as many of them as possible to be sure the talker is kept talking. Listeners should contribute nothing more than “active listening” to the communication.

- The “observer” should note the behaviors and skills used by the listener and the effects they seemed to have on the communication process.

- These roles are rotated until each student has played every role.

- The instructor will lead a discussion of what the observers saw and what happened with the talkers and listeners. The discussion focuses on what behaviors from the posted list have been present, which have been absent, and how the communication has been affected by the listener's actions.

Source: Adapted from the presentation entitled “An Experiential Exercise to Teach Active Listening,” presented at the Organizational Behavior Teaching Conference, Macomb, IL, 1995.

EXERCISE 30

Upward Appraisal

Instructions

- Form workgroups as assigned by your instructor.

- The instructor will leave the room.

- Convene in your assigned workgroups for a period of 10 minutes. Create a list of comments, problems, issues, and concerns you would like to have communicated to the instructor in regard to the course experience to date. Remember, your interest in the exercise is twofold: (a) to communicate your feelings to the instructor and (b) to learn more about the process of giving and receiving feedback.

- Select one person from the group to act as spokesperson in communicating the group's feelings to the instructor.

- The spokespersons should briefly convene to decide on what physical arrangement of chairs, tables, and so forth is most appropriate to conduct the feedback session. The classroom should then be rearranged to fit the desired specifications.

- While the spokespersons convene, persons in the remaining groups should discuss how they expect the forthcoming communications event to develop. Will it be a good experience for all parties concerned? Be prepared to critically observe the actual communication process.

- The instructor should be invited to return, and the feedback session will begin. Observers should make notes so that they may make constructive comments at the conclusion of the exercise.

- Once the feedback session is complete, the instructor will call on the observers for comments, ask the spokespersons for reactions, and open the session to discussion.

EXERCISE 31

360° Feedback

Contributed by Timothy J. Serey, Northern Kentucky University

Introduction

The time of performance reviews is often a time of genuine anxiety for many organizational members. On the one hand, it is an important organizational ritual and a key part of the human resources function. Organizations usually codify the process and provide a mechanism to appraise performance. On the other hand, it is rare for managers to feel comfortable with this process. Often, they feel discomfort over “playing God.” One possible reason for this is that managers rarely receive formal training about how to provide feedback. From the manager's point of view, if done properly, giving feedback is at the very heart of his or her job as “coach” and “teacher.” It is an investment in the professional development of another person, rather than the punitive element we so often associate with hearing from “the boss.” From the subordinate's perspective, most people want to know where they stand, but this is usually tempered by a fear of “getting it in the neck.” In many organizations, it is rare to receive straight, non-sugar-coated feedback about where you stand.

Instructions

- Review the section of the book dealing with feedback before you come to class. It is also helpful if individuals make notes about their perceptions and feelings about the course before they come to class.

- Groups of students should discuss their experiences, both positive and negative, in this class. Each group should determine the dimensions of evaluating the class itself and the instructor. For example, students might select criteria that include the practicality of the course, the way the material is structured and presented (e.g., lecture or exercises), and the instructor's style (e.g., enthusiasm, fairness).

- Groups select a member to represent them in a subgroup that next provides feedback to the instructor before the entire class.

- The student audience then provides the subgroup with feedback about their effectiveness in this exercise. That is, the larger class provides feedback to the subgroup about the extent to which students actually put the principles of effective feedback into practice (e.g., descriptive, not evaluative; specific, not general).

Source: Adapted from Timothy J. Serey, Journal of Management Education 17:2 (May 1993). © 1993 by Sage Publications, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Sage Publications.

EXERCISE 32

Role Analysis Negotiation

Contributed by Paul Lyons, Frostburg State University

Introduction

A role is the set of various behaviors people expect from a person (or group) in a particular position. These role expectations occur in all types of organizations, such as one's place of work, school, family, clubs, and the like. Role ambiguity takes place when a person is confused about the expectations of the role. And sometimes, a role will have expectations that are contradictory—for example, being loyal to the company when the company is breaking the law.

The Role Analysis Technique, or RAT, is a method for improving the effectiveness of a team or group. RAT helps to clarify role expectations, and all organization members have responsibilities that translate to expectations. Determination of role requirements, by consensus—involving all concerned—will ultimately result in more effective and mutually satisfactory behavior. Participation and collaboration in the definition and analysis of roles by group members should result in clarification regarding who is to do what as well as increase the level of commitment to the decisions made.

Instructions

Working alone, carefully read the course syllabus that your instructor has given you. Make a note of any questions you have about anything for which you need clarification or understanding. Pay particular attention to the performance requirements of the course. Make a list of any questions you have regarding what, specifically, is expected of you in order for you to be successful in the course. You will be sharing this information with others in small groups.

Source: Adapted from Paul Lyons, “Developing Expectations with the Role Analysis Technique, Journal of Management Education 17:3 (August 1993), pp. 386–389. © Sage Publications.

EXERCISE 33

Lost at Sea

Introduction

Consider this situation. You are adrift on a private yacht in the South Pacific when a fire of unknown origin destroys the yacht and most of its contents. You and a small group of survivors are now in a large raft with oars. Your location is unclear, but you estimate being about 1,000 miles south-southwest of the nearest land. One person has just found in her pockets five $1 bills and a packet of matches. Everyone else's pockets are empty. The following items are available to you on the raft.

| A | B | C | |

| Sextant | ___ | ___ | |

| Shaving mirror | ___ | ___ | |

| 5 gallons of water | ___ | ___ | |

| Mosquito netting | ___ | ___ | |

| 1 survival meal | ___ | ___ | |

| Maps of Pacific Ocean | ___ | ___ | |

| Floatable seat cushion | ___ | ___ | |

| 2 gallons oil-gas mix | ___ | ___ | |

| Small transistor radio | ___ | ___ | |

| Shark repellent | ___ | ___ | |

| 20 square feet black plastic | ___ | ___ | |

| 1 quart of 20-proof rum | ___ | ___ | |

| 15 feet of nylon rope | ___ | ___ | |

| 24 chocolate bars | ___ | ___ | |

| Fishing kit | ___ | ___ |

Instructions

- Working alone, rank in Column A the 15 items in order of their importance to your survival (“1” is most important, and “15” is least important).

- Working in an assigned group, arrive at a “team” ranking of the 15 items and record this ranking in Column B. Appoint one person as group spokesperson to report your group rankings to the class.

- Do not write in Column C until further instructions are provided by your instructor.

Source: Adapted from “Lost at Sea: A Consensus-Seeking Task,” in J. William Pfeiffer and John E. Jones (eds.), The 1975 Handbook for Group Facilitators. Used with permission of University Associates, Inc., La Jolla, CA.

EXERCISE 34

Entering the Unknown

Contributed by Michael R. Manning, New Mexico State University; Conrad N. Jackson, MPC Inc., Huntsville, Alabama; and Paula S. Weber, New Mexico Highlands University

Instructions

- Form into groups of four or five members. In each group spend a few minutes reflecting on members' typical entry behaviors in new situations and their behaviors when they are in comfortable settings.

- According to the instructor's directions, students count off to form new groups of four or five members each.

- The new groups spend the next 15 to 20 minutes getting to know each other. There is no right or wrong way to proceed, but all members should become more aware of their entry behaviors. They should act in ways that can help them realize a goal of achieving comfortable behaviors with their group.

- Students review what has occurred in the new groups, giving specific attention to the following questions:

- What topics did your group discuss (content)? Did these topics involve the “here and now” or were they focused on “there and then”?

- What approach did you and your group members take to the task (process)? Did you try to initiate or follow? How? Did you ask questions? Listen? Respond to others? Did you bring up topics?

- Were you more concerned with how you came across or with how others came across to you? Did you play it safe? Were you open? Did you share things even though it seemed uncomfortable or risky? How was humor used in your group? Did it add or detract?

- How do you feel about the approach you took or the behaviors you exhibited? Was this hard or easy? Did others respond the way you had anticipated? Is there some behavior you would like to do more of, do better, or do less of?

- Were your behaviors the ones you had intended (goals)?

- Responses to these questions are next discussed by the class as a whole. (Note: Responses will tend to be mixed within a group, but between groups there should be more similarity.) This discussion helps individuals become aware of and understand their entry behaviors.

- Optional individuals have identified their entry behaviors; each group can then spend 5 to 10 minutes discussing members' perceptions of each other:

- What behaviors did they like or find particularly useful? What did they dislike?

- What were your reactions to others? What ways did they intend to come across? Did you see others in the way they had intended to come across?

(Alternatively, if there is concern about the personal nature of this discussion, ask the groups to discuss what they liked/didn't like without referring to specific individuals.)

EXERCISE 35

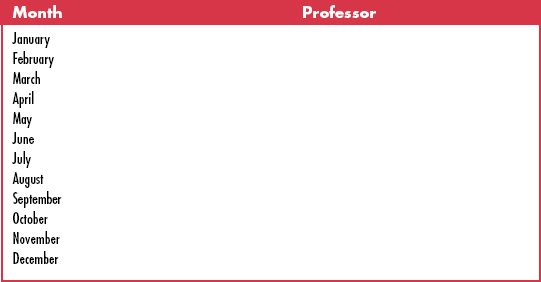

Vacation Puzzle

Contributed by Barbara G. McCain and Mary Khalili, Oklahoma City University

Instructions

Can you solve this puzzle? Give it a try and then compare your answers with those of classmates. Remember your communicative skills!

Puzzle

Khalili, McCain, Middleton, Porter, and Quintaro teach at Oklahoma City University. Each gets two weeks of vacation a year. Last year, each took his or her first week in the first five months of the year and his or her second week in the last five months. If each professor took each of his or her weeks in a different month from the other professors, in which months did each professor take his or her first and second week?

Here are the facts:

- McCain took her first week before Khalili, who took hers before Porter; for their second week, the order was reversed.

- The professor who vacationed in March also vacationed in September.

- Quintaro did not take her first week in March or April.

- Neither Quintaro nor the professor who took his or her first week in January took his or her second week in August or December.

- Middleton took her second week before McCain but after Quintaro.

Source: Adapted to classroom activity by Dr. Mary Khalili.

EXERCISE 36

The Ugli Orange

Introduction

In most work settings, people need other people to do their job, benefit the organization, and forward their career. Getting things done in organizations requires us to work together in cooperation, even though the ultimate objectives of those other people may be different from our own. Your task in the present exercise is learning how to achieve this cooperation more effectively.

Instructions

- The class will be divided into pairs. One student in each pair will read and prepare the role of Dr. Roland, and one will play the role of Dr. Jones (role descriptions to be distributed by instructor). Students should read their respective role descriptions and prepare to meet with their counterpart (see steps 2 and 3).

- At this point the group leader will read a statement. The instructor will indicate that he or she is playing the role of Mr. Cardoza, who owns the commodity in question. The instructor will tell you:

- How long you have to meet with the other

- What information the instructor will require at the end of your meeting

After the instructor has given you this information, you may meet with the other firm's representative and determine whether you have issues you can agree to.

- Following the meetings (negotiations), the spokesperson for each pair will report any agreements reached to the entire class. The observer for any pair will report on negotiation dynamics and the process by which agreement was reached.

- Questions to consider:

- Did you reach a solution? If so, what was critical to reaching that agreement?

- Did you and the other negotiator trust one another? Why or why not?

- Was there full disclosure by both sides in each group? How much information was shared?

- How creative and/or complex were the solutions? If solutions were very complex, why do you think this occurred?

- What was the impact of having an “audience” on your behavior? Did it make the problem harder or easier to solve?

Source: Adapted from Douglas T. Hall et al., Experiences in Management and Organizational Behavior, 3rd ed. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1988). Originally developed by Robert J. House. Adapted by D. T. Hall and R. J. Lewicki, with suggested modifications by H. Kolodny and T. Ruble.

EXERCISE 37

Conflict Dialogues

Contributed by Edward G. Wertheim, Northeastern University

Instructions

- Think of a conflict situation at work or at school and try to re-create a segment of the dialogue that gets to the heart of the conflict.

- Write notes on the conflict dialogue using the following format.

Introduction

- Background

- My goals and objectives

- My strategy

- Assumptions I am making

Dialogue (re-create part of the following dialogue and try to put what you were really thinking in parentheses).

- Me:

- Other:

- Me:

- Other,

- etc.

3. Share your situation with members of your group. Read the dialogue to them, perhaps asking someone to play the role of “other.”

4. Discuss with the group:

- The style of conflict resolution you used (confrontation, collaboration, avoidance, etc.)

- The triggers to the conflict, that is, what really set you off and why

- Whether or not you were effective

- Possible ways of handling this differently

5. Choose one dialogue from within the group to share with the class. Be prepared to discuss your analysis and also possible alternative approaches and resolutions for the situation described.

EXERCISE 38

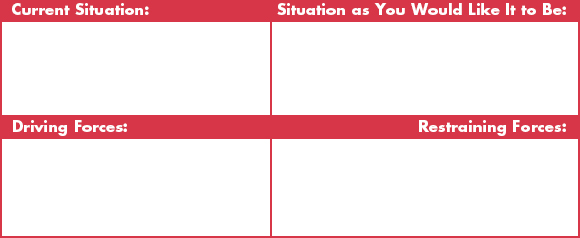

Force-Field Analysis

Instructions

- Choose a situation in which you have high personal stakes (for example, how to get a better grade in course X; how to get a promotion; how to obtain a position).

- Using a version of the Sample Force-Field Analysis Form provided, apply the technique to your situation.

- Describe the situation as it now exists.

- Describe the situation as you would like it to be.

- Identify those “driving forces”—the factors that are presently helping to move things in the desired direction.

- Identify those “restraining forces”—the factors that are presently holding things back from moving in the desired direction.

- Try to be as specific as possible in yours answers in relation to your situation. You should attempt to be exhaustive in your listing of these forces. List them all!

- Now go back and classify the strength of each force as weak, medium, or strong. Do this for both the driving and the restraining forces.