13

The Leadership Process

Although many people think of leadership as the behavior of leaders, it is actually generated in interactions and relationships between people. Understanding leadership as a process opens our eyes to the fact that leadership is co-produced by leaders and followers working together in organizational contexts. ![]()

What's Inside?

![]() Bringing OB to LIFE

Bringing OB to LIFE

BUILDING CHARISMA THROUGH POLISHED RHETORIC

![]() Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

BOSSES ARE TO BE OBEYED AND MY JOB IS TO COMPLY. OR IS IT?

![]() Checking Ethics in OB

Checking Ethics in OB

WORKERS SHARE THEIR SALARY SECRETS

![]() Finding the Leader in You

Finding the Leader in You

GOOGLE'S TRIUMVIRATE GIVES WAY TO NEW LEADERSHIP STRUCTURE

![]() OB in Popular Culture

OB in Popular Culture

LEADER IDENTITY AND FORREST GUMP

![]() Research Insight

Research Insight

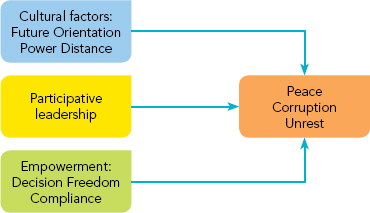

PARTICIPATORY LEADERSHIP AND PEACE

Chapter at a Glance

- What Is Leadership?

- What Is Followership?

- What Do We Know about Leader–Follower Relationships?

- What Do We Mean by Leadership as a Collective Process?

Leadership

![]() FORMAL AND INFORMAL LEADERSHIP

FORMAL AND INFORMAL LEADERSHIP ![]() LEADERSHIP AS SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION

LEADERSHIP AS SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION

IMPLICIT LEADERSHIP THEORIES

When we think of leadership, we often think of leaders. But leaders are only one element of leadership. Other key elements are followers, leader–follower relationships, and context. It is only when all these elements come together effectively that leadership is produced. For this reason, leadership should be thought of as a process.

The leadership process shown in the nearby figure is co-created by leaders and followers acting in context. Leadership is generated when acts of leading (e.g., influencing) are combined with acts of following (e.g., deferring). It represents an influence relationship between two or more people who depend on one another for attainment of mutual goals.1 The implication of this is that leadership is not only about the actions of leaders. It also involves the actions of followers who contribute to, or detract from, leaders' attempts to influence.

Leadership is an influence process generated when acts of leading (e.g., influencing) are combined with acts of following (e.g., deferring) as individuals work together to attain mutual goals.

Because following is so important to leading, we could almost say that it is in following that leadership is created. If others do not follow then, even if a person has a leadership position, he or she is not really a leader. The person may be a manager—but not a leader. For example, when students in a class act up and do not respect the teacher, they are not following and the teacher is not leading. The teacher may try to use position power to manage the situation, but in this case the teacher is acting as a manager rather than a leader.

Leadership influence can be located in one person (i.e., a “leader”) or be distributed throughout the group (i.e., collective leadership). For example, some teams have one project leader who everyone follows. Other groups may be more self-managing, where team members share the leadership function and responsibilities. While in the past leadership was largely the domain of formal managerial leaders, in today's environments leadership is broadly distributed more throughout organizations, with everyone expected to play their part.

Formal and Informal Leadership

Formal and Informal Leadership

Leadership processes occur both inside and outside of formal positions and roles. When leadership is exerted by individuals appointed or elected to positions of formal authority, it is called formal leadership. Managers, teachers, ministers, politicians, and student organization presidents are all formal leaders. Leadership can also be exerted by individuals who do not hold formal roles but become influential due to special skills or their ability to meet the needs of others. These individuals are informal leaders.2 Informal leaders can include opinion leaders, change agents, and idea champions.

Formal leadership is exerted by persons appointed or elected to positions of formal authority in organizations.

Informal leaders is exerted by persons who become influential due to special skills or their ability to meet the needs of others.

Whereas formal leadership involves top-down influence flows, informal leadership can flow in any direction: up, down, across, and even outside the organization. Informal leadership allows us to recognize the importance of upward leadership (or “leading-up”). Upward leadership occurs when individuals at lower levels act as leaders by influencing those at higher levels. This concept of leadership flowing upward is often missed in discussions of leadership in organizations, but it is absolutely critical for organizational change and effectiveness.

Upward leadership occurs when leaders at lower levels influence those at higher levels to create change.

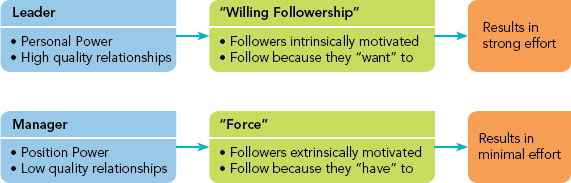

Regardless of whether it is formal or informal, a key to effective leadership is “willing followership,” as shown in Figure 13.1. Willing followership means that others follow because they want to, not because they have to. This is closely related to the concept of power. When leaders operate from a willing followership model, others follow out of intrinsic motivation and power comes from personal sources. This differs from more compliance-based approaches-common to managers who aren't leaders, where others follow out of extrinsic motivation and power is more position based. Managers who are also effective leaders have both position and personal power. On the other hand, informal leaders who do not have formal positions can only operate through personal power.

FIGURE 13.1 The role of “willing followership” in leadership.

Leadership as Social Construction

Leadership as Social Construction

Understanding leadership as a process helps us see that leadership is socially constructed. The social construction of leadership means that leadership is co-created in relational interactions among people acting in context. Because of this, it cannot be meaningfully separated from context. Each leadership situation is unique, having its own particular dynamics, variables, and players. There is no one-size-fits-all solution in leadership.

social construction of leadership The social construction of leadership means that leadership is constructed and produced in social and relational interactions among people acting in context.

Social construction approaches see leadership as socially defined. They recognize leaders and followers as relational beings who “constitute” each other in dynamic, unfolding relational contexts.3 In other words, whether you are a leader or a follower depends on the nature of the interactions you have with other people. Because of this, communication and the everyday interactions of people are a key element of constructionist approaches to leadership.

Leadership as Identity Construction An example of social construction can be seen in DeRue and Ashford's model of the leadership identity construction process. This model shows how individuals negotiate identities as leaders and followers.4 As seen in Figure 13.2, the identity construction process involves individuals “claiming” an identity (as a leader or follower) and others affirming or “granting” that identity by going along with the claim. Claiming refers to actions people take to assert their identity as a leader or follower. Granting refers to actions people take to bestow an identity of a leader or follower onto another person.5

The leadership identity construction process involves individuals negotiating identities as leaders and followers.

Claiming refers to actions people take to assert their identity as a leader or follower.

Granting refers to actions people take to bestow an identity of a leader or follower onto another person.

We can see the identity construction process occurring every time a new group is formed. When there is no designated leader, group members negotiate who will be leaders and who will be followers. For example, some might say, “I am willing to take the leader role,” or “Leadership is not really my thing, so I prefer to follow.” It may also be more implicit, with some people doing more influencing and organizing and others doing more deferring and performing.

This process occurs even when there is a designated leader. In these cases it may be more subtle, however, such as when individuals choose not to follow the designated leader (i.e., when they do not grant the leader claim). In groups we often see informal norms emerging around leader and follower grants and claims in the form of people supporting or resisting each other's claims.

FIGURE 13.2 DeRue and Ashford Leadership Identity Construction Process.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

Leader identity construction has important implications, particularly for those who are high in motivation to lead.6 Although these individuals may want to lead, if others do not grant them a leadership identity their efforts will not succeed. It also helps us understand why some individuals seem to find themselves in a leader role even if they don't want to be. For these “natural leaders,” leadership is thrust upon them by others who grant them leadership identities regardless of their desire to claim leadership (see the “OB in Popular Culture” feature on Forrest Gump).

Motivation to lead is the extent to which individuals choose to assume leadership training, roles and responsibilities.

The leadership identity construction process brings a new understanding to the importance of followership. Contrary to views that depict followers as passive bystanders to leaders, identity construction shows that followers play an important role in leadership by (a) granting claims to leaders and (b) claiming roles as followers. When these grants and claims do not align—for example, when followers do not grant leaders' claims or when followers do not accept their own role as followers—the result is conflict and lack of legitimacy. Unless the problems are worked through, individuals will not be able to negotiate compatible identities. In these cases conflict will prevail, and the leadership process will break down.

Implicit Leadership Theories

Implicit Leadership Theories

A key element affecting whether leadership claims will be granted lies in the “implicit theories” we hold about leadership. Implicit leadership theories are beliefs or understanding about the attributes associated with leaders and leadership.7 They can vary widely depending on our experiences and understandings of leadership. For example, some people believe leaders are charismatic, so they look for charismatic traits and behaviors in those vying for leadership status. Others believe leaders are directive and assertive, so they grant leadership status to those who take charge. Still others believe leaders are confident and considerate, so they identify leaders as those who have innovative and interesting ideas and involve others in bringing the idea to fruition.

Implicit leadership theories are our beliefs or understanding about the attributes associated with leaders and leadership.

Implicit theories cause us to naturally classify people as leaders or nonleaders. We are often not aware this process is occurring. It is based in the cognitive categorization processes associated with perception and attribution. These processes help us quickly and easily handle the overwhelming amounts of information we receive from our environments every day. The categorization process is often particularly salient when we are faced with new information. For example, on the first day of class did you look around the room and find yourself making assessments of the teacher, and even your classmates? If so, you did this using your cognitive categories and implicit theories.

To understand your own implicit leadership theories, think about the factors you associate with leadership. What traits and characteristics come to mind? Take a minute and make a list of those attributes. Now look at the sidebar on spotting implicit leadership prototypes.8 How does your list compare? Did you identify the same prototypical leader behaviors as found in research? What is the nature of your implicit theory? Is it more positive, such as sensitivity, dedication, intelligence, and strength, or is it more negative, involving leaders' tendencies to dominate, control, or manipulate others? Why do you think you have the implicit theory you do? What experiences you've had make you see leadership in this way?

Followership

![]() WHAT IS FOLLOWERSHIP?

WHAT IS FOLLOWERSHIP? ![]() HOW DO FOLLOWERS SEE THEIR ROLES?

HOW DO FOLLOWERS SEE THEIR ROLES?

HOW DO LEADERS SEE FOLLOWER ROLES?

Until very recently, followership has not been given serious consideration in leadership research. We are infatuated with leaders, but often disparage followers. Think about how often you are told the importance of being an effective leader. Now think about the times when you have been told it is important to be an effective follower—has it ever happened? If you are like most people, you have received recognition and accolades for leadership but rarely have you been encouraged or rewarded for being a follower.

What Is Followership?

What Is Followership?

Followership represents the capacity or willingness to follow a leader. It is a process through which individuals choose how they will engage with leaders to co-produce leadership and its outcomes. These co-productions can take many forms. For example, it may be heavily leader dominated, with passive followers who comply or go along. Or it may be a partnership, in which leaders and followers work collaboratively to produce leadership outcomes.

Followership is a process through which individuals choose how they will engage with leaders to co-produce leadership and its outcomes.

Our infatuation with leaders at the expense of followers is called the romance of leadership: the tendency to attribute all organizational outcomes—good or bad—to the acts and doings of leaders.9 The romance of leadership reflects our needs and biases for strong leaders who we glorify or demonize in myths and stories of great and heroic leaders. We see it in our religious teachings, our children's fairy tales, and in news stories about political and business leaders.

The romance of leadership refers to the tendency to attribute organizational outcomes (both good and bad) to the acts and doings of leaders.

The problem with the romance of leadership is that its corollary is the “subordination of followership.”10 The subordination of followership means that while we heroize (or demonize) leaders, we almost completely disregard followers. Leo Tolstoy's description of the French Revolution provides an excellent example. According to Tolstoy, the French Revolution was the product of the “spectacle of an extraordinary movement of millions of men” all over Europe and crossing decades, but “historians . . . lay before us the sayings and doings of some dozens of men in one of the buildings in the city of Paris,” and the detailed biography and actions of one man, to whom it is all attributable: Napoleon. To overcome the problem of the romance of leadership, we need to better understand the role of followership in the leadership process.

How Do Followers See Their Roles?

How Do Followers See Their Roles?

Followers have long been considered in leadership research, but mainly from the standpoint of how they see leaders. The question we need to consider is this: How do followers see their own role? And how do leaders see the follower role? Research is now beginning to offer new insight into these issues.

The Social Construction of Followership One of the first studies to examine follower views was a qualitative investigation in which individuals were asked to describe the characteristics and behaviors they associate with a follower (subordinate) role.11 The findings support the socially constructed nature of followership and leadership in that, according to followers, they hold certain beliefs about how they should act in relation to leaders but whether they can act on these beliefs depends on context.

Some followers hold passive beliefs, viewing their roles in the classic sense of following—that is, passive, deferential, and obedient to authority. Others hold proactive beliefs, viewing their role as expressing opinions, taking initiative, and constructively questioning and challenging leaders. Proactive beliefs are particularly strong among “high potentials”—those identified by their organizations as demonstrating strong potential to be promoted to higher-level leadership positions in their organization.

Because social construction is dependent on context, individuals are not always able to act according to their beliefs. For example, individuals holding proactive beliefs reported not being able to be proactive in authoritarian or bureaucratic work climates. These environments suppress their ability to take initiative and speak up, often leaving them feeling frustrated and stifled—not able to work to their potential. In empowering climates, however, they work with leaders to co-produce positive outcomes. Individuals with passive beliefs are often uncomfortable in empowering climates because their natural inclination is to follow rather than be empowered. In these environments they report feeling stressed by leaders' demands, and uncomfortable with requests to be more proactive. Passive followers are more comfortable in authoritarian climates where they receive more direction from leaders.

CHECKING ETHICS IN OB

Follower Role Orientation Follower beliefs are also being studied in research on follower role orientation. Follower role orientation represents the beliefs followers hold about the way they should engage and interact with leaders to meet the needs of the work unit.12 It reflects how followers define their role, how broadly they perceive the tasks associated with it, and how to approach a follower role to be effective.

Follower role orientation is defined as the beliefs followers hold about the way they should engage and interact with leaders to meet the needs of the work unit.

FIGURE 13.3 Followership in Context.

Findings show that followers with hierarchical, power distance orientation believe leaders are in a better position than followers to make decisions and determine direction.13 These individuals have lower self-efficacy, meaning they have less confidence in their ability to execute on their own, and they demonstrate higher obedience to leaders. They depend on leaders for structure and direction, which they follow without question. These followers report working in contexts of greater hierarchy of authority and lower job autonomy. This may be because these contexts are attractive to them, or it may be because those with more proactive follower orientations are less likely to remain in these environments.

Power distance orientation is the extent to which one accepts that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally.

Individuals with a proactive follower orientation approach their role from the standpoint of partnering with leaders to achieve goals.14 These individuals are higher in proactive personality and self-efficacy. They believe followers are important contributors to the leadership process and that a strong follower role (e.g., voice) is necessary for accomplishing the organizational mission. Proactive followers tend to work in environments that support and reinforce their followership beliefs—that is, lower hierarchy of authority, greater autonomy, and higher supervisor support. These environments are important because proactive followers need support for their challenging styles. They need to trust leaders and to know that they will not be seen as overstepping their bounds.

Proactive follower orientation reflects the belief that followers should act in ways that are helpful, useful, and productive to leadership outcomes.

The issue that is less clear is what managers want from followers. It seems that managers want voice, as long as that voice is provided in constructive ways. However, findings with obedience are not significant, indicating that managers may be mixed on whether obedience is positive or negative. This is true regardless of whether it comes from those with a power distance or proactive follower orientation. Therefore, we are not quite sure how obedience plays into followership. Do managers want obedience? Do only some managers want it, or do managers want only certain types of obedience? It turns out that although we have spent decades learning about what followers want from leaders, we still know very little about what leaders prefer in terms of follower behaviors and styles. Research is now underway to better investigate the manager side of the leadership story.

How Do Leaders See Follower Roles?

How Do Leaders See Follower Roles?

One area that helps us understand the manager's view is the study of implicit followership theories.15 Research on implicit followership theories takes the approach described in implicit leadership theory research but reverses it—asking leaders (i.e., managers) to describe characteristics associated with followers (e.g., effective followers, ineffective followers). It then analyzes the data to identify prototypical and anti-prototypical follower characteristics.

Implicit followership theories are preconceived notions about prototypical and antiprototypical followership behaviors and characteristics.

Findings shown in the sidebar on the next page indicate that characteristics associated with good followers include being industrious, having enthusiasm, and being a good organizational citizen.16 Characteristics associated with ineffective followers (i.e., anti-prototypical characteristics) include conformity, insubordination, and incompetence. Of these anti-prototypical traits, it appears that incompetence is the most impactful. In other words, leaders see incompetence as the greatest factor associated with ineffective followership.

What is interesting about the findings on prototypes and anti-prototypes (see the sidebar) is that they may show why we are uncertain of what managers desire from followers. What managers see as insubordination and incompetence, followers may see as proactive follower behaviors. There can be a fine line between these behaviors as provided by followers, and whether leaders are ready and able to effectively receive them. Although it hasn't been studied yet in research, we can be pretty sure that a key factor in influencing how managers view and receive proactive follower behaviors is the quality of the relationship between the manager and the subordinate.

The Leader—Follower Relationship

![]() LEADER–MEMBER EXCHANGE THEORY

LEADER–MEMBER EXCHANGE THEORY ![]() SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

HOLLANDER'S IDIOSYNCRASY CREDIT

Among the strongest findings in leadership research are studies showing that the nature of leader–follower relationships matter. When relationships are good, outcomes are positive. When relationships are bad, outcomes are negative, and potentially even destructive.

Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) Theory

Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) Theory

The underlying premise of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory is that leaders (i.e., managers) have differentiated relationships with followers (i.e., subordinates).17 With some subordinates, managers have high-quality LMX relationships, characterized by trust, respect, liking, and loyalty. With other subordinates, managers have low-quality LMX relationships, characterized by lack of trust, respect, liking, and loyalty. Whereas the former (high LMX relationships) are more like partnerships between managers and subordinates in co-producing leadership, the latter (low LMX relationships) are more like traditional supervision, with managers supervising and monitoring and subordinates complying (or maybe resisting).

Leader–member exchange (LMX) is the study of manager–subordinate relationship quality.

Leader–follower relationships are important because they are differentially related to leadership and work outcomes. As you would expect, when relationship quality is high it has all kinds of benefits: Performance is better, subordinates are more satisfied and feel more supported, commitment and citizenship are higher, and turnover is reduced. When relationship quality is low, outcomes are not only negative, they can also be destructive. At the very least, workers in low LMX relationships are less productive and have more negative job attitudes. At their worst, relationships are hostile, leading to abuse or even sabotage.18

The implications of leader–member exchange theory are very clear. Bad relationships are counterproductive for individuals and organizations, whereas good relationships bring tremendous benefits. If you have a bad relationship with your boss, you can expect it to negatively impact your work and possibly your career. In organizations, bad relationships create negative environments and poor morale. They drain organizations of the energy needed to perform, adapt, and thrive.

Social Exchange Theory

Social Exchange Theory

To avoid these problems, we need to work to develop better-quality relationships throughout the organization. The question is, how?

Social exchange theory helps explain the social dynamics behind relationship building. According to social exchange theory, relationships develop through exchanges—actions contingent upon rewarding reactions. We engage in exchanges every day when we say something or do something for another and those actions are rewarded or not rewarded. Relationships develop when exchanges are mutually rewarding and reinforcing. When exchanges are one sided or not satisfactory, relationships will not develop effectively, and will likely deteriorate or extinguish.

Social exchange theory describes how relationships initiate and develop through processes of exchange and reciprocity.

At the core of social exchange is the norm of reciprocity, the idea that when one party does something for another an obligation is generated, and that party is indebted to the other until the obligation is repaid.19 We see this all the time when someone does us a favor and then, depending on how close we are to them, we feel indebted to pay them back. If the relationship is close (e.g., family) we don't worry about paying back right away because we know it will be repaid in some way in the future. If the exchange is with someone we don't know as well (e.g., a classmate we just met), we are more anxious to repay so that the other knows we are “good” for it.

The norm of reciprocity says that when one party does something for another, that party is indebted to the other until the obligation is repaid.

The norm of reciprocity can be seen as involving three components.20 Equivalence represents the extent to which the amount of what is given back is roughly the same as what was received (e.g., the exact same or something different). Immediacy refers to the time span of reciprocity—how quickly the repayment is made (e.g., immediately or an indeterminate length of time). Interest represents the motive the person has in making the exchange. Interest can range from pure self-interest, to mutual interest, to other interest (pure concern for the other person).

Equivalence is the extent to which the amount given back is roughly the same as what was received.

Immediacy is how quickly the repayment is made.

Interest is the motive behind the exchange.

The way in which these components work together varies by the quality of leader–follower relationships. When relationships are first forming, or if they are low quality, reciprocity involves greater equivalence (we want back what we give), immediacy is low (we expect payback relatively quickly), and exchanges are based on self-interest (we are watching out for ourselves). As relationships develop and trust is built, equivalence reduces (we don't expect exact repayment), the time span of reciprocity extends (we aren't concerned about payback—we may bank it for when we need it at some time in the future), and exchanges become more mutually or other (rather than self) interested.

What makes this process social and not economic is that it is based on trust. Trust is based on the belief regarding the intention and ability of the other to repay. Economic exchanges are necessarily devoid of trust. The reason we make economic contracts is to create a legal obligation in case one party breaks the contract. In social exchange, trust is the foundational element upon which exchanges occur. If one party demonstrates that they are not trustworthy, the other party will see this and stop exchanging—and the relationship will degenerate.

Trust in social exchange is based on the belief in the intention and ability of the other to repay.

If we want to build effective relationships, therefore, we need to pay attention to reciprocity and social exchange processes. We need to make sure that we are engaging in exchanges, that we are doing so based on reciprocity, and that the exchanges are mutually satisfying and rewarding for all involved.

Hollander's Idiosyncrasy Credits

Hollander's Idiosyncrasy Credits

Another way to view the nature of exchange in relationships is idiosyncrasy credit theory, developed by social psychologist Edwin Hollander in the 1950s.21 Idiosyncrasy credits represent our ability to violate norms with others based on whether we have enough “credits” to cover the violation. If we have enough credits, we can get away with idiosyncrasies (i.e., deviations from expected norms) as long as the violation does not exceed the amount of credits. If we do not have enough credits, the violation will create a deficit. When deficits become large enough, or go on for too long, our account becomes “bankrupt,” and the deviations will no longer be tolerated, resulting in deterioration of relationships.

Idiosyncrasy credits refer to our ability to violate norms with others based on whether we have enough “credits” to cover the violation.

Idiosyncrasy credits offer a fun and simple way to think about some key concepts we need to keep in mind in relationship building. The main point is to manage your balances. If you are expending credits by behaving in idiosyncratic ways (deviating from expected norms), then you have to stop spending and start building. If you have a rich account and the relationship is flying high, you can afford to expend some credits by acting in a quirky way or doing things that might not be seen as positively in the other's eyes. Others will be willing to stick with you—as long as you don't go into a deficit.

Collective Leadership

![]() DISTRIBUTED LEADERSHIP

DISTRIBUTED LEADERSHIP ![]() CO-LEADERSHIP

CO-LEADERSHIP ![]() SHARED LEADERSHIP

SHARED LEADERSHIP

Relational interactions are the foundation of leadership, and relational approaches have allowed us to understand that leadership is more aptly described as a collective rather than an individual process. Collective leadership considers leadership not as a property of individuals and their behaviors but as a social phenomenon constructed in interaction. It advocates a shift in focus from traits and characteristics of leaders to a focus on the shared activities and interactive processes of leadership.

Collective leadership represents views of leadership not as a property of individuals and their behaviors but as a social phenomenon constructed in interaction.

Distributed Leadership

Distributed Leadership

One of the first areas to recognize leadership as a collective process was distributed leadership research, distinguishing between “focused” and “distributed” forms of leadership. This research draws heavily on systems and process theory, and locates leadership in the relationships and interactions of multiple actors and the situations in which they are operating.22

Distributed leadership sees leadership as a group phenomenon that is distributed among individuals.

Distributed leadership is based on three main premises. First, leadership is an emergent property of a group or network of interacting individuals, i.e., it is co-constructed in interactions among people. Second, distributed leadership is not clearly bounded. It occurs in context, and therefore it is affected by local and historical influences. Third, distributed leadership draws from the variety of expertise across the many, rather than relying on the limited expertise of one or a few leaders. In this way it is a more democratic and inclusive form of leadership than hierarchical models.23

Leadership from this view is seen in the day-to-day activities and interactions of people working in organizations. Rather than simply being a hierarchical construct, it occurs in small, incremental, and emergent everyday acts that go on in organizations. These emergent acts, interacting with large-scale change efforts from the top, can be mutually reinforcing to produce emergence and adaptability in organizations. Hence, leadership is about learning together and constructing meaning and knowledge collaboratively and collectively. For this to happen, though, formal leaders must let go of some of their authority and control and foster consultation and consensus over command and control.24

Co-Leadership

Co-Leadership

Another form of collective leadership is co-leadership. Co-leadership occurs when top leadership roles are structured in ways that no single individual is vested with the power to unilaterally lead.25 Co-leadership can be found in professional organizations (e.g., law firms that have partnerships), the arts (the artistic side and administrative side), and healthcare (where power is divided between the community, administration, and medical sectors). Co-leadership has been used in some very famous and large businesses (e.g., Google, Goldman-Sachs).

Co-leadership occurs when leadership is divided so that no one person has unilateral power to lead.

Co-leadership helps overcome problems related to the limitations of a single individual and of abuses of power and authority. It is more common today because challenges facing organizations are often too complex for one individual to handle. Co-leadership allows organizations to capitalize on the complementary and diverse strengths of multiple individuals. These forms are sometimes referred to as constellations, or collective leadership in which members play roles that are specialized (i.e., each operates in a particular area of expertise), differentiated (i.e., avoiding overlap that would create confusion), and complementary (i.e., jointly cover all required areas of leadership).26

Shared Leadership

Shared Leadership

According to shared leadership approaches, leadership is a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals, or both.27 This influence process occurs both laterally—among team members—and vertically, with the team leader. Vertical leadership is formal leadership; shared leadership is distributed leadership that emerges from within team dynamics. The main objective of shared leadership approaches is to understand and find alternate sources of leadership that will impact positively on organizational performance.

Shared leadership is a dynamic, interactive influence process among team members working to achieve goals.

In shared leadership, leadership can come from outside or inside the team. Within a team, leadership can be assigned to one person, rotate across team members, or be shared simultaneously as different needs arise across time. Outside the team, leaders can be formally designated. Often these nontraditional leaders are called coordinators or facilitators. A key part of their job is to provide resources to their unit and serve as a liaison with other units.

According to the theory, the key to successful shared leadership and team performance is to create and maintain conditions for that performance. This occurs when vertical and shared leadership efforts are complementary. Although a wide variety of characteristics may be important for the success of a specific effort, five important characteristics have been identified across projects: (1) efficient, goal-directed effort; (2) adequate resources; (3) competent, motivated performance; (4) a productive, supportive climate; and (5) a commitment to continuous improvement.28 The distinctive contribution of shared leadership approaches is in widening the notion of leadership to consider participation of all team members while maintaining focus on conditions for team effectiveness.

13 Study Guide

Key Questions and Answers

What is leadership?

- Leadership occurs in acts of leading and following as individuals work together to attain mutual goals.

- Formal leadership is found in positions of authority in organizations, whereas informal leadership is found in individuals who become influential due to special skills or abilities.

- Leadership involves an identity construction process in which individuals negotiate identities as leaders and followers through claiming and granting.

- Implicit leadership theories are beliefs or understanding about the attributes associated with leaders and leadership.

What is followership?

- Followership represents a process through which individuals choose how they will engage with leaders to co-produce leadership and its outcomes.

- Romance of leadership is the tendency to attribute organizational outcomes (both good and bad) to the acts and doings of leaders; its corollary is the “subordination of followership.”

- The social construction of followership shows that followers hold beliefs about how they should act in relation to leaders, but whether they can act on these beliefs depends on context.

- Those with power distance orientation accept that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally, whereas those with proactive follower orientations believe followers should act in ways that are helpful and productive to leadership outcomes.

- Implicit followership theories show managers' views of characteristics associated with effective and ineffective followership.

What do we know about leader–follower relationships?

- Leader–member exchange theory shows that managers have differentiated relationships with subordinates depending on the amount of trust, respect, and loyalty in the relationship.

- These relationships are important because they are differentially related to leadership and work outcomes. When relationship quality is high, performance is better, subordinates are more satisfied and supported, commitment and citizenship are higher, and turnover is reduced.

- Relationships develop through processes of social exchange based on the norm of reciprocity (i.e., when one party does something for another, an obligation is generated until it is repaid).

- Reciprocity is determined based on three components: equivalence (whether the amount given back is same as what was received), immediacy (how quickly the repayment is made), and interest (the motive behind the exchange).

- Idiosyncrasy credits mean that when we have enough credits built up in relationships with others, we can get away with idiosyncrasies (i.e., deviations from expected norms) as long as the violation does not exceed the amount of credits.

What do we mean by leadership as a collective process?

- Collective leadership advocates a shift in focus from traits and characteristics of leaders to a focus on the shared activities and interactive processes of leadership.

- Distributed leadership sees leadership as drawing from the variety of expertise across the many, rather than relying on the limited expertise of one or a few leaders.

- Co-leadership is when top leadership roles are structured in ways that no single individual is vested with the power to unilaterally lead.

- Shared leadership defines leadership as a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals, or both.

- Shared leadership occurs both laterally, among team members, and vertically, with the team leader. The main objective is to understand and find alternate sources of leadership that will impact positively on organizational performance.

Terms to Know

Claiming (p. 284)

Co-leadership (p. 295)

Collective leadership (p. 294)

Distributed leadership (p. 294)

Equivalence (p. 293)

Followership (p. 288)

Follower role orientation (p. 289)

Formal leadership (p. 282)

Granting (p. 284)

Idiosyncrasy credits (p. 294)

Immediacy (p. 293)

Implicit followership theories (p. 290)

Implicit leadership theories (p. 286)

Informal leaders (p. 282)

Interest (p. 293)

Leader–member exchange (LMX) (p. 292)

Leadership (p. 282)

Leadership identity construction process (p. 284)

Motivation to lead (p. 285)

Norm of reciprocity (p. 293)

Power distance orientation (p. 290)

Proactive follower orientation (p. 290)

Romance of leadership (p. 288)

Shared leadership (p. 296)

social construction of leadership (p. 284)

Social exchange theory (p. 293)

Trust (p. 293)

Upward leadership (p. 282)

Self-Test 13

Multiple Choice

Multiple Choice

- Leadership is a process of __________.

- (a) leading and following

- (b) deferring and obeying

- (c) managing and supervising

- (d) influencing and resisting

- We could almost say that it is in ________ that leadership is created.

- (a) positions

- (b) authority

- (c) following

- (d) hierarchy

- A type of leadership that is often missed in discussions of leadership is __________ leadership.

- (a) face-to-face

- (b) downward

- (c) hierarchical

- (d) upward

- _________ occurs through processes of claiming and granting.

- (a) Followership

- (b) Leadership identity construction

- (c) Implicit theory

- (d) Status

- People use _________ in deciding whether to grant a leadership claim.

- (a) implicit theories

- (b) social constructions

- (c) collective leadership

- (d) social exchange

- ________ involves the choice of how to engage with leaders in producing leadership.

- (a) Implicit theories

- (b) Followership

- (c) Informal leadership

- (d) Reciprocity

- Power distance is an example of ________.

- (a) an implicit followership theory

- (b) upward leadership

- (c) the leadership process

- (d) a follower role orientation

- Individuals who engage in voice likely have a __________.

- (a) weak feedback orientation

- (b) prototypical leadership theory

- (c) proactive follower orientation

- (d) power distance orientation

- When someone returns a favor to relieve an obligation very quickly it is an example of ____________.

- (a)economic exchange

- (b)interest

- (c)equivalence

- (d)immediacy

- The obligation created when someone does you a favor is ________.

- (a) feedback orientation

- (b) the norm of reciprocity

- (c) implicit followership theories

- (d) distributed leadership

- A rule of thumb for whether you can violate norms in a relationship is to not overexpend your ____________.

- (a) idiosyncrasy credits

- (b) relational disclosures

- (c) low LMX

- (d) reciprocity

- __________ says that leadership is an emergent property of a group or network of interacting individuals.

- (a) Leadership identity construction

- (b) Distributed leadership

- (c) Leader–member exchange theory

- (d) Social exchange theory

- If a manager and subordinate have a lot of trust and support for one another, we can say they have a _________.

- (a) weak norm of reciprocity

- (b) idiosyncratic relationship

- (c) low LMX relationship

- (d) high LMX relationship

- When the leadership role at the top is divided among multiple people, it is called ___________.

- (a) collective leadership

- (b) distributed leadership

- (c) co-leadership

- (d) shared leadership

- Conformity is an example of __________.

- (a) power distance orientation

- (b) prototypical followership

- (c) anti-prototypical followership

- (d) constructive orientation

Short Response

Short Response

16. What does it mean when we say leadership is socially constructed?

17. How do followers see their role in leadership?

18. How does the norm of reciprocity work in relationship development?

19. Why are scholars talking about collective leadership?

Applications Essay

Applications Essay

20. Your roommate is student government president and has been having trouble getting others to listen to him. Each night it is a different complaint about how terrible the other people in student government are, and how they are lazy and not willing to do anything. You really want to help him figure out this problem. How do you go about it?

Steps to Further Learning 13

Top Choices from The OB Skills Workbook

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook found at the back of the book are suggested for Chapter 13.

“Instead of putting charismatic leadership on an unreachable pedestal, perhaps learning specific charismatic communication techniques is a pathway to success.”

“Instead of putting charismatic leadership on an unreachable pedestal, perhaps learning specific charismatic communication techniques is a pathway to success.”