10

Conflict and Negotiation

Although cooperation and collaboration are ideal conditions, conflict and negotiation are ever present in team and organizational dynamics. Everyone has to be able to deal with them in positive ways. The word “yes” can often get things back on track when tensions build and communication falters in teamwork and interpersonal relationships. ![]()

What's Inside?

![]() Bringing OB to LIFE

Bringing OB to LIFE

KEEPING IT ALL TOGETHER WHEN MOM'S THE BREADWINNER

![]() Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

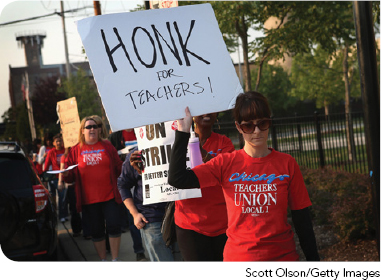

LABOR AND MANAGEMENT SIDES DISAGREE. IS A STRIKE THE ANSWER?

![]() Checking Ethics in OB

Checking Ethics in OB

BLOGGING CAN BE FUN, BUT BLOGGERS BEWARE

![]() Finding the Leader in You

Finding the Leader in You

ALAN MULALLY LEADS BY TRANSFORMING AN EXECUTIVE TEAM

![]() OB in Popular Culture

OB in Popular Culture

CONFLICT AND THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA

![]() Research Insight

Research Insight

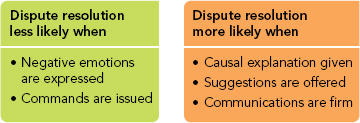

WORDS AFFECT OUTCOMES IN ONLINE DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Chapter at a Glance

- What Is the Nature of Conflict in Organizations?

- How Can Conflict Be Managed?

- What Is the Nature of Negotiation in Organizations?

- What Are Alternative Strategies for Negotiation?

Conflict in Organizations

![]() TYPES OF CONFLICT

TYPES OF CONFLICT ![]() LEVELS OF CONFLICT

LEVELS OF CONFLICT

FUNCTIONAL AND DYSFUNCTIONAL CONFLICT ![]() CULTURE AND CONFLICT

CULTURE AND CONFLICT

We all need skills to work well with others who don't always agree with us, even in situations that are complicated and stressful.1 Conflict occurs whenever disagreements exist in a social situation over issues of substance, or whenever emotional antagonisms create frictions between individuals or groups.2 Team leaders and members can spend considerable time dealing with conflicts. Sometimes they are direct participants, and other times they act as mediators or neutral third parties to help resolve conflicts between other people.3 The fact is that conflict dynamics are inevitable in the workplace, and it's best to know how to handle them.4

Conflict occurs when parties disagree over substantive issues or when emotional antagonisms create friction between them.

Types of Conflict

Types of Conflict

Conflicts in teams, at work, and in our personal lives occur in at least two basic forms: substantive and emotional. Both types are common, ever present, and challenging. How well prepared are you to deal successfully with them?

Substantive conflict is a fundamental disagreement over ends or goals to be pursued and the means for their accomplishment.5 A dispute with one's boss or other team members over a plan of action to be followed, such as the marketing strategy for a new product, is an example of substantive conflict. When people work together every day, it is only normal that different viewpoints on a variety of substantive workplace issues will arise. At times people will disagree over such things as team and organizational goals, the allocation of resources, the distribution of rewards, policies and procedures, and task assignments.

Substantive conflict involves fundamental disagreement over ends or goals to be pursued and the means for their accomplishment.

Emotional conflict involves interpersonal difficulties that arise over feelings of anger, mistrust, dislike, fear, resentment, and the like.6 This conflict is commonly known as a “clash of personalities.” How many times, for example, have you heard comments such as “I can't stand working with him” or “She always rubs me the wrong way” or “I wouldn't do what he asked if you begged me”? When emotional conflicts creep into work situations, they can drain energies and distract people from task priorities and goals. Yet, they emerge in a wide variety of settings and are common in teams, among co-workers, and in superior-subordinate relationships.

Emotional conflict involves interpersonal difficulties that arise over feelings of anger, mistrust, dislike, fear, resentment, and the like.

Levels of Conflict

Levels of Conflict

Our first tendency may be to think of conflict as something that happens between two people, something we call “interpersonal conflict.” Conflicts in teams and organizations take other forms as well, and each needs to be understood. The full range of conflicts that we experience at work includes those emerging from the interpersonal, intrapersonal, intergroup, and interorganizational levels.

Interpersonal conflict occurs between two or more individuals who are in opposition to one another. It may be substantive, emotional, or both. Two teammates debating each other aggressively on the merits of hiring a specific job applicant for the team is an example of a substantive interpersonal conflict. Two persons continually in disagreement over each other's choice of words, work attire, personal appearance, or manners is an example of an emotional interpersonal conflict. Both types of interpersonal conflict often arise in the performance assessment process where the traditional focus has been on one person passing judgment on another. Sometimes the issue is one of sub-stance—“Just exactly what does ‘poor’ performance mean?” asks the subordinate. Others times it is emotional—“I don't care if it is okay. Your long hair is a misfit with the rest of the team,” says the boss. Even as performance reviews turn toward peer and 360° types, similar issues can make assessments difficult interpersonal moments.

Interpersonal conflict occurs between two or more individuals in opposition to each other.

Intrapersonal conflict is tension experienced within the individual due to actual or perceived pressures from incompatible goals or expectations. Approach-approach conflict occurs when a person must choose between two positive and equally attractive alternatives. An example is when someone has to choose between a valued promotion in the organization or a desirable new job with another firm. Avoidance-avoidance conflict occurs when a person must choose between two negative and equally unattractive alternatives. An example is being asked either to accept a job transfer to another town in an undesirable location or to have one's employment with an organization terminated. Approach-avoidance conflict occurs when a person must decide to do something that has both positive and negative consequences. An example is being offered a higher-paying job with responsibilities that make unwanted demands on one's personal time.

Intrapersonal conflict occurs within the individual because of actual or perceived pressures from incompatible goals or expectations.

Intergroup conflict occurs between teams, perhaps ones competing for scarce resources or rewards or ones whose members have emotional problems with one another. The classic example is conflict among functional groups or departments, such as marketing and manufacturing. Sometimes these conflicts have substantive roots, such as marketing focusing on sales revenue goals and manufacturing focusing on cost-efficiency goals. Other times such conflicts have emotional roots, as when egotists in their respective departments want to look better than each other in a certain situation. Intergroup conflict is quite common in organizations, and it can make the coordination and integration of task activities very difficult.7 The growing use of cross-functional teams and task forces is one way of trying to minimize such conflicts by improving horizontal communication.

Intergroup conflict occurs among groups in an organization.

Interorganizational conflict is most commonly thought of in terms of the rivalry that characterizes firms operating in the same markets. A good example is business competition between U.S. multinationals and their global rivals: Ford versus Hyundai, or AT&T versus Vodaphone, or Boeing versus Airbus, for example. But interorganizational conflict is a much broader issue than that represented by market competition alone. Other common examples include disagreements between unions and the organizations employing their members, between government regulatory agencies and the organizations subject to their surveillance, between organizations and their suppliers, and between organizations and outside activist groups.

Interorganizational conflict occurs between organizations.

Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict

Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict

Any type of conflict in teams and organizations can be upsetting both to the individuals directly involved and to others affected by its occurrence. It can be quite uncomfortable, for example, to work on a team where two co-workers are continually hostile toward each other, or where your team is constantly battling another to get resources from top management attention. As Figure 10.1 points out, however, it's important to recognize that conflict can have a functional or constructive side as well as a dysfunctional or destructive side.

FIGURE 10.1 The two faces of conflict: functional conflict and dysfunctional conflict.

Functional conflict, also called constructive conflict, results in benefits to individuals, the team, or the organization. This positive conflict can bring important problems to the surface so they can be addressed. It can cause decisions to be considered carefully and perhaps reconsidered to ensure that the right path of action is being followed. It can increase the amount of information used for decision making. It can offer opportunities for creativity that can improve performance. Indeed, an effective manager or team leader is able to stimulate constructive conflict in situations in which satisfaction with the status quo is holding back needed change and development.

Functional conflict results in positive benefits to the group.

Dysfunctional conflict, or destructive conflict, works to the disadvantage of an individual or team. It diverts energies, hurts group cohesion, promotes interpersonal hostilities, and creates an overall negative environment for workers. This type of conflict occurs, for example, when two team members are unable to work together because of interpersonal differences—a destructive emotional conflict—or when the members of a work unit fail to act because they cannot agree on task goals—a destructive substantive conflict. Destructive conflicts of these types can decrease performance and job satisfaction as well as contribute to absenteeism and job turnover. Managers and team leaders should be alert to destructive conflicts and be quick to take action to prevent or eliminate them—or at least minimize any harm done.

Dysfunctional conflict works to the group's or organization's disadvantage.

Culture and Conflict

Culture and Conflict

Society today shows many signs of cultural wear and tear in social relationships. We experience difficulties born of racial tensions, homophobia, gender gaps, and more. They arise from tensions among people who are different from one another in some way. They are also a reminder that cultural differences must be considered for their conflict potential. Consider the cultural dimension of time orientation. When persons from short-term cultures such as the United States try to work with persons from long-term cultures such as Japan, the likelihood of conflict developing is high. The same holds true when individualists work with collectivists and when persons from high-power-distance cultures work with those from low-power-distance cultures.8

People who are not able or willing to recognize and respect cultural differences can cause dysfunctional conflicts in multicultural teams. On the other hand, members with cultural intelligence and sensitivity can help the team to unlock its performance advantages. Consider these comments from members of a joint European and American project team at Corning. American engineer: “Something magical happens. Europeans are very creative thinkers; they take time to really reflect on a problem to come up with the very best theoretical solution. Americans are more tactical and practical—we want to get down to developing a working solution as soon as possible.” French teammate: “The French are more focused on ideas and concepts. If we get blocked in the execution of those ideas, we give up. Not the Americans. They pay more attention to details, processes, and time schedules. They make sure they are prepared and have involved everyone in the planning process so that they won't get blocked. But it's best if you mix the two approaches. In the end, you will achieve the best results.”9

Conflict Management

![]() STAGES OF CONFLICT

STAGES OF CONFLICT ![]() HIERARCHICAL CAUSES OF CONFLICT

HIERARCHICAL CAUSES OF CONFLICT

CONTEXTUAL CAUSES OF CONFLICT

INDIRECT CONFLICT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

DIRECT CONFLICT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Conflict can be addressed in many ways, but true conflict resolution—a situation in which the underlying reasons for dysfunctional conflict are eliminated—can be elusive. When conflicts go unresolved, the stage is often set for future conflicts of the same or related sort. Rather than trying to deny the existence of conflict or settle on a temporary resolution, it is always best to deal with important conflicts in such ways that they are completely resolved.10 This requires a good understanding of the stages of conflict, the potential causes of conflict, and indirect and direct approaches to conflict management.

Conflict resolution occurs when the reasons for a conflict are eliminated.

Stages of Conflict

Stages of Conflict

Most conflicts develop in the stages shown in the nearby figure. Conflict antecedents establish the conditions from which conflicts are likely to emerge. When the antecedent conditions become the basis for substantive or emotional differences between people or groups, the stage of perceived conflict exists. Of course, this perception may be held by only one of the conflicting parties.

There is quite a difference between perceived and felt conflict. When conflict is felt, it is experienced as tension that motivates the person to take action to reduce feelings of discomfort. For conflict to be resolved, all parties should perceive the conflict and feel the need to do something about it.

Manifest conflict is expressed openly in behavior. At this stage removing or correcting the antecedents results in conflict resolution, whereas failing to do so results in conflict suppression. With suppression, no change in antecedent conditions occurs even though the manifest conflict behaviors may be temporarily controlled. This occurs, for example, when one or both parties choose to ignore conflict in their dealings with one another. Conflict suppression is a superficial and often temporary state that leaves the situation open to future conflicts over similar issues. Only true conflict resolution establishes conditions that eliminate an existing conflict and reduce the potential for it to recur in the future.

Hierarchical Causes of Conflict

Hierarchical Causes of Conflict

The nature of organizations as hierarchical systems provides a convenient setting for conflicts as individuals and teams try to work with one another. Vertical conflict occurs between levels and commonly involves supervisor-subordinate and team leader-team member disagreements over resources, goals, deadlines, or performance results. Horizontal conflict occurs between persons or groups working at the same organizational level.

FIGURE 10.2 Structural differentiation as a potential source of conflict among functional teams.

Hierarchical conflicts commonly arise from goal incompatibilities, resource scarcities, or purely interpersonal factors. Line-staff conflict involves disagreements between line and staff personnel over who has authority and control over decisions on matters such as budgets, technology, and human resource practices. Also common are role ambiguity conflicts that occur when the communication of task expectations is unclear or upsetting in some way, such as a team member receiving different expectations from the leader and other members. Conflict is always likely when people are placed in ambiguous situations where it is hard to understand who is responsible for what, and why.

Contextual Causes of Conflict

Contextual Causes of Conflict

The context of the organization as a complex network of interacting subsystems is a breeding ground for conflicts. Task and workflow interdependencies cause disputes and open disagreements among people and teams who are required to cooperate to meet challenging goals.11 Conflict potential is especially great when interdependence is high—that is, when a person or group must rely on or ask for contributions from one or more others to achieve its goals. Conflict escalates with structural differentiation, when different teams and work units pursue different goals with different time horizons as shown in Figure 10.2. Conflict also develops out of domain ambiguities, when individuals or teams lack adequate task direction or goals and misunderstand such things as customer jurisdiction or scope of authority.

Actual or perceived resource scarcity can foster destructive conflict. Working relationships are likely to suffer as individuals or teams try to position themselves to gain or retain maximum shares of a limited resource pool. They are also likely to resist having their resources redistributed to others.

Power or value asymmetries in work relationships can also create conflict. They exist when interdependent people or teams differ substantially from one another in status and influence or in values. Conflict resulting from asymmetry is likely, for example, when a low-power person needs the help of a high-power person who does not respond, when people who hold dramatically different values are forced to work together on a task, or when a high-status person is required to interact with and perhaps be dependent on someone of lower status.

Indirect Conflict Management Strategies

Indirect Conflict Management Strategies

Most people will tell you that not all conflict in teams and organizations can be resolved by getting everyone involved to adopt new attitudes, behaviors, and stances toward one another. Think about it. Aren't there likely to be times when personalities and emotions prove irreconcilable? In such cases an indirect or structural approach to conflict management can often help. It uses such strategies as reduced interdependence, appeals to common goals, hierarchical referral, and alterations in the use of mythology and scripts to deal with the conflict situation.

Managed Interdependence When workflow conflicts exist, managers can adjust the level of interdependency among teams or individuals.12 One simple option is decoupling, or taking action to eliminate or reduce the required contact between conflicting parties. In some cases, team tasks can be adjusted to reduce the number of required points of coordination. The conflicting parties are separated as much as possible from one another.

Buffering is another approach that can be used when the inputs of one team are the outputs of another. The classic buffering technique is to build an inventory, or buffer, between the teams so that any output slowdown or excess is absorbed by the inventory and does not directly pressure the target group. Although it reduces conflict, this technique is increasingly out of favor because it increases inventory costs.

Conflict can sometimes be reduced by assigning people to serve as liaisons between groups that are prone to conflict.13 Persons in these linking-pin roles are expected to understand the operations, members, needs, and norms of their host teams. They are supposed to use this knowledge to help the team work better with others in order to accomplish mutual tasks.

Appeals to Common Goals An appeal to common goals can focus the attention of conflicting individuals and teams on one mutually desirable conclusion. This elevates any dispute to the level of common ground where disagreements can be put in perspective. In a course team where members are arguing over content choices for a PowerPoint presentation, for example, it might help to remind everyone that the goal is to impress the instructor and get an “A” for the presentation and that this is only possible if everyone contributes their best.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

Upward Referral Upward referral uses the chain of command for conflict resolution.14 Problems are moved up from the level of conflicting individuals or teams for more senior managers to address. Although tempting, this has limitations. If conflict is severe and recurring, the continual use of upward referral may not result in true conflict resolution. Higher managers removed from day-to-day affairs may fail to see the real causes of a conflict, and attempts at resolution may be superficial. In addition, busy managers may tend to blame the people involved and perhaps act quickly to replace them.

Altering Scripts and Myths In some situations, conflict is superficially managed by scripts, or behavioral routines, that are part of the organization's culture.15 The scripts become rituals that allow the conflicting parties to vent their frustrations and to recognize that they are mutually dependent on one another. An example is a monthly meeting of department heads that is held presumably for purposes of coordination and problem solving but actually becomes just a polite forum for agreement.16 Managers in such cases know their scripts and accept the difficulty of truly resolving any major conflicts. For instance, by sticking with the script, expressing only low-key disagreement, and then quickly acting as if everything has been taken care of, the managers can leave the meeting with everyone feeling a superficial sense of accomplishment.

Direct Conflict Management Strategies

Direct Conflict Management Strategies

In addition to the indirect conflict management strategies just discussed, it is also very important to understand how conflict management plays out in face-to-face fashion. Figure 10.3 shows five direct conflict management strategies that vary in their emphasis on cooperativeness and assertiveness in the interpersonal dynamics of the situation. Although true conflict resolution can occur only when a conflict is dealt with through a solution that allows all conflicting parties to “win,” the reality is that direct conflict management may also pursue lose-lose and win-lose outcomes.17

FIGURE 10.3 Five direct conflict management strategies.

Lose-Lose Strategies Lose-lose conflict occurs when nobody really gets what he or she wants in a conflict situation. The underlying reasons for the conflict remain unaffected, and a similar conflict is likely to occur in the future. Lose-lose outcomes are likely when the conflict management strategies involve little or no assertiveness. Avoidance is the extreme where no one acts assertively and everyone simply pretends the conflict doesn't exist and hopes it will go away. Accommodation (or smoothing) as it is sometimes called, involves playing down differences among the conflicting parties and highlighting similarities and areas of agreement. This peaceful coexistence ignores the real essence of a conflict and often creates frustration and resentment. Compromise occurs when each party shows moderate assertiveness and cooperation and is ultimately willing to give up something of value to the other. Because no one gets what they really wanted, the antecedent conditions for future conflicts are established.

Avoidance involves pretending a conflict does not really exist.

Accommodation (or smoothing) involves playing down differences and finding areas of agreement.

Compromise occurs when each party gives up something of value to the other.

Win-Lose Strategies In win-lose conflict, one party achieves its desires at the expense and to the exclusion of the other party's desires. This is a high-assertiveness and low-cooperativeness situation. It may result from outright competition in which one party achieves a victory through force, superior skill, or domination. It may also occur as a result of authoritative command, whereby a formal authority such as manager or team leader simply dictates a solution and specifies what is gained and what is lost by whom. Win-lose strategies fail to address the root causes of the conflict and tend to suppress the desires of at least one of the conflicting parties. As a result, future conflicts over the same issues are likely to occur.

Competition seeks victory by force, superior skill, or domination.

Authoritative command uses formal authority to end conflict.

Win-Win Strategies Win-win conflict is achieved by a blend of both high cooperativeness and high assertiveness.18 Collaboration and problem solving involve recognition by all conflicting parties that something is wrong and needs attention. It stresses gathering and evaluating information in solving disputes and making choices. All relevant issues are raised and openly discussed. Win-win outcomes eliminate the reasons for continuing or resurrecting the conflict because nothing has been avoided or suppressed.

Collaboration and problem solving involve recognition that something is wrong and needs attention through problem solving.

The ultimate test for collaboration and problem solving is whether or not the conflicting parties see that the solution to the conflict: (1) achieves each party's goals, (2) is acceptable to both parties, and (3) establishes a process whereby all parties involved see a responsibility to be open and honest about facts and feelings. When success in each of these areas is achieved, the likelihood of true conflict resolution is greatly increased. However, this process often takes time and consumes lots of energy, to which the parties must be willing to commit. Collaboration and problem solving aren't always feasible, and the other strategies are sometimes useful if not preferred.19 As the “You Should Know . . .” features points out, each of the conflict management strategies may have advantages under certain conditions.

Negotiation

![]() ORGANIZATIONAL SETTINGS FOR NEGOTIATION

ORGANIZATIONAL SETTINGS FOR NEGOTIATION

NEGOTIATION GOALS AND OUTCOMES ![]() ETHICAL ASPECTS OF NEGOTIATION

ETHICAL ASPECTS OF NEGOTIATION

Picture yourself trying to make a decision. Situation: You are about to order a new tablet device for a team member in your department. Then another team member submits a request for one of a different brand. Your boss says that only one brand can be ordered. Situation: You have been offered a new job in another city and want to take it, but you are disappointed with the salary. You've heard friends talk about how they “negotiated” better offers when taking jobs. You are concerned about the costs of relocating and would like a signing bonus as well as a guarantee of an early salary review.

The preceding examples are just two of the many situations that involve negotiation—the process of making joint decisions when the parties involved have different preferences.20 Negotiation has special significance in teams and work settings, where disagreements are likely to arise over such diverse matters as wage rates, task objectives, performance evaluations, job assignments, work schedules, work locations, and more.

Negotiation is the process of making joint decisions when the parties involved have different preferences.

Organizational Settings for Negotiation

Organizational Settings for Negotiation

Managers and team leaders should be prepared to participate in at least four major action settings for negotiations. In a two-party negotiation, the manager negotiates directly with one other person. In a group negotiation, the manager is part of a team or group whose members are negotiating to arrive at a common decision. In an intergroup negotiation, the manager is part of a team that is negotiating with another group to arrive at a decision regarding a problem or situation affecting both. In a constituency negotiation, each party represents a broader constituency—for example, representatives of management and labor negotiating a collective bargaining agreement.

Negotiation Goals and Outcomes

Negotiation Goals and Outcomes

Two important goals are at stake in any negotiation: substance goals and relationship goals. Substance goals deal with outcomes that relate to the content issues under negotiation. The dollar amount of a salary offer in a recruiting situation is one example. Relationship goals deal with outcomes that relate to how well people involved in the negotiation and any constituencies they may represent are able to work with one another once the process is concluded. An example is the ability of union members and management representatives to work together effectively after a labor contract dispute has been settled.

Effective negotiation occurs when substance issues are resolved and working relationships are maintained or even improved. In practice, think of this in terms of two criteria for effective negotiation:

Effective negotiation occurs when substance issues are resolved and working relationships are maintained or improved.

- Quality of outcomes—The negotiation results in a “quality” agreement that is wise and satisfactory to all sides.

Criteria of effective negotiation

- Harmony in relationships—The negotiation is “harmonious” and fosters rather than inhibits good interpersonal relations.

Ethical Aspects of Negotiation

Ethical Aspects of Negotiation

It would be ideal if everyone involved in a negotiation followed high ethical standards of conduct, but this goal can get sidetracked by an overemphasis on self-interests. The motivation to behave ethically in negotiations can be put to the test by each party's desire to get more than the other from the negotiation and/or by a belief that there are insufficient resources to satisfy all parties.21 After the heat of negotiations dies down, the parties may try to rationalize or explain away questionable ethics as unavoidable, harmless, or justified. Such after-the-fact rationalizations can have long-run negative consequences, such as not being able to achieve one's wishes again the next time. At the very least, the unethical party may be the target of revenge tactics by those who were disadvantaged. Once some people have behaved unethically in one situation, furthermore, they may become entrapped by such behavior and may be more likely to display it again in the future.22

Negotiation Strategies

![]() APPROACHES TO DISTRIBUTIVE NEGOTIATION

APPROACHES TO DISTRIBUTIVE NEGOTIATION

HOW TO GAIN INTEGRATIVE AGREEMENTS ![]() COMMON NEGOTIATION PITFALLS

COMMON NEGOTIATION PITFALLS

THIRD-PARTY ROLES IN NEGOTIATION

When we think about negotiating for something, perhaps cars and salaries are the first things that pop into mind. But people in organizations are constantly negotiating over not only just pay and raises, but also such things as work rules or assignments, rewards, and access to any variety of scarce resources—money, time, people, facilities, equipment, and so on. The strategy used can have a major influence on how the negotiation transpires and its outcomes.

Two broad negotiation strategies differ markedly in approach and possible outcomes. Distributive negotiation focuses on positions staked out or declared by conflicting parties. Each party tries to claim certain portions of the available “pie” whose overall size is considered fixed. Integrative negotiation, sometimes called principled negotiation, focuses on the merits of the issues. Everyone involved tries to enlarge the available pie and find mutually agreed-on ways of distributing it, rather than stake claims to certain portions of it.23 Think of the conversations you overhear and are part of in team situations. The notion of “my way or the highway” is analogous to distribution negotiation; “Let's find a way to make this work for both of us” is more akin to integrative negotiation.

Distributive negotiation focuses on positions staked out or declared by the parties involved, each of whom is trying to claim certain portions of the available pie.

Integrative negotiation focuses on the merits of the issues, and the parties involved try to enlarge the available pie rather than stake claims to certain portions of it.

Approaches to Distributive Negotiation

Approaches to Distributive Negotiation

Participants in distributive negotiation usually approach it as a win-lose episode. Things tend to unfold in one of two directions—a hard battle for dominance or a soft and quick concession. Neither one nor the other delivers great results.

“Hard” distributive negotiation takes place when each party holds out to get its own way. This leads to competition, whereby each party seeks dominance over the other and tries to maximize self-interests. The hard approach may lead to a win-lose outcome in which one party dominates and gains, or it can lead to an impasse.

“Soft”distributive negotiation takes place when one party or both parties make concessions just to get things over with. This soft approach leads to accommodation—in which one party gives in to the other—or to compromise—in which each party gives up something of value in order to reach agreement. In either case at least some latent dissatisfaction is likely to remain.

Figure 10.4 illustrates classic two-party distributive negotiation by the example of the graduating senior negotiating a job offer with a recruiter.24 Look at the situation first from the graduate's perspective. She has told the recruiter that she would like a salary of $60,000; this is her initial offer. However, she also has in mind a minimum reservation point of $50,000—the lowest salary that she will accept for this job. Thus she communicates a salary request of $60,000 but is willing to accept one as low as $50,000. The situation is somewhat the reverse from the recruiter's perspective. His initial offer to the graduate is $45,000, and his maximum reservation point is $55,000; this is the most he is prepared to pay.

FIGURE 10.4 The bargaining zone in classic two-party negotiation.

The bargaining zone is the range between one party's minimum reservation point and the other party's maximum reservation point. In Figure 10.4, the bargaining zone is $50,000 to $55,000. This is a positive bargaining zone since the reservation points of the two parties overlap.

The bargaining zone is the range between one party's minimum reservation point and the other party's maximum.

Whenever a positive bargaining zone exists, bargaining has room to unfold. Had the graduate's minimum reservation point been greater than the recruiter's maximum reservation point (for example, $57,000), no room would have existed for bargaining. Classic two-party bargaining always involves the delicate tasks of first discovering the respective reservation points—one's own and the other's. Progress can then be made toward an agreement that lies somewhere within the bargaining zone and is acceptable to each party.

How to Gain Integrative Agreements

How to Gain Integrative Agreements

The integrative approach to negotiation is less confrontational than the distributive, and it permits a broader range of alternatives to be considered in the negotiation process. From the outset there is much more of a win-win orientation. Even though it may take longer, the time, energy, and effort needed to negotiate an integrated agreement can be well worth the investment. Always, the integrative or principled approach involves a willingness to negotiate based on the merits of the situation. The foundations for gaining truly integrative agreements can be described as supportive attitudes, constructive behaviors, and good information.25

Attitudinal Foundations There are three attitudinal foundations of integrative agreements. First, each party must approach the negotiation with a willingness to trust the other party. This is a reason why ethics and maintaining relationships are so important in negotiations. Second, each party must convey a willingness to share information with the other party. Without shared information, effective problem solving is unlikely to occur. Third, each party must show a willingness to ask concrete questions of the other party. This further facilitates information sharing.

Behavioral Foundations All behavior during a negotiation is important for both its actual impact and the impressions it leaves behind. This means the following behavioral foundations of integrative agreements must be carefully considered and included in any negotiator's repertoire of skills and capabilities:

- Separate people from the problem.

How to gain integrative agreements

- Don't allow emotional considerations to affect the negotiation.

- Focus on interests rather than positions.

- Avoid premature judgments.

- Keep the identification of alternatives separate from their evaluation.

- Judge possible agreements by set criteria or standards.

Information Foundations The information foundations of integrative agreements are substantial. They involve each party becoming familiar with the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA). That is, each party must know what he or she will do if an agreement cannot be reached. Both negotiating parties must identify and understand their personal interests in the situation. They must know what is really important to them in the case at hand and, they must come to understand what the other party values.

Common Negotiation Pitfalls

Common Negotiation Pitfalls

The negotiation process is admittedly complex on ethical and many other grounds. It is subject to all the possible confusions of complex, and sometimes even volatile, interpersonal and team dynamics. And as if this isn't enough, negotiators need to guard against some common negotiation pitfalls.26

One common pitfall is the tendency to stake out your negotiating position based on the assumption that in order to gain your way, something must be subtracted from the gains of the other party. This myth of the fixed pie is a purely distributive approach to negotiation. The whole concept of integrative negotiation is based on the premise that the pie can sometimes be expanded or used to the maximum advantage of all parties, not just one.

Second, the possibility of escalating commitment is high when negotiations begin with parties stating extreme demands. Once demands have been stated, people become committed to them and are reluctant to back down. Concerns for protecting one's ego and saving face may lead to the irrational escalation of a conflict. Self-discipline is needed to spot tendencies toward escalation in one's own behavior as well as in the behavior of others.

Third, negotiators often develop overconfidence that their positions are the only correct ones. This can lead them to ignore the other party's needs. In some cases negotiators completely fail to see merits in the other party's position-merits that an outside observer would be sure to spot. Such overconfidence makes it harder to reach a positive common agreement.

Fourth, communication problems can cause difficulties during a negotiation. It has been said that “negotiation is the process of communicating back and forth for the purpose of reaching a joint decision.”27 This process can break down because of a telling problem-the parties don't really talk to each other, at least not in the sense of making themselves truly understood. It can also be damaged by a hearing problem-the parties are unable or unwilling to listen well enough to understand what the other is saying. Indeed, positive negotiation is most likely when each party engages in active listening and frequently asks questions to clarify what the other is saying. Each party occasionally needs to “stand in the other party's shoes” and to view the situation from the other's perspective.28

Third-Party Roles in Negotiation

Third-Party Roles in Negotiation

Negotiation may sometimes be accomplished through the intervention of third parties, such as when stalemates occur and matters appear to be irresolvable under current circumstances. In a process called alternative dispute resolution, a neutral third party works with persons involved in a negotiation to help them resolve impasses and settle disputes. There are two primary forms through which it is implemented.

In arbitration, such as the salary arbitration now common in professional sports, the neutral third party acts as a “judge” and has the power to issue a decision that is binding on all parties. This ruling takes place after the arbitrator listens to the positions advanced by the parties involved in a dispute. In mediation, the neutral third party tries to engage the parties in a negotiated solution through persuasion and rational argument. This is a common approach in labor-management negotiations, where trained mediators acceptable to both sides are called in to help resolve bargaining impasses. Unlike an arbitrator, the mediator is not able to dictate a solution.

In arbitration a neutral third party acts as judge with the power to issue a decision binding for all parties.

In mediation a neutral third party tries to engage the parties in a negotiated solution through persuasion and rational argument.

10 Study Guide

Key Questions and Answers

What is the nature of conflict in organizations?

- Conflict appears as a disagreement over issues of substance or emotional antagonisms that create friction between individuals or teams.

- Conflict situations in organizations occur at intrapersonal, interpersonal, intergroup, and interorganizational levels.

- Moderate levels of conflict can be functional for performance, stimulating effort and creativity.

- Too little conflict is dysfunctional when it leads to complacency; too much conflict is dysfunctional when it overwhelms us.

How can conflict be managed?

- Conflict typically develops through a series of stages, beginning with antecedent conditions and progressing into manifest conflict.

- Indirect conflict management strategies include appeals to common goals, upward referral, managed interdependence, and the use of mythology and scripts.

- Direct conflict management strategies of avoidance, accommodation, compromise, competition, and collaboration show different tendencies toward cooperativeness and assertiveness.

- Lose-lose conflict results from avoidance, smoothing or accommodation, and compromise; win-lose conflict is associated with competition and authoritative command; win-win conflict is achieved through collaboration and problem solving.

What is the nature of negotiation in organizations?

- Negotiation is the process of making decisions and reaching agreement in situations where participants have different preferences.

- Managers may find themselves involved in various types of negotiation situations, including two-party, group, intergroup, and constituency negotiation.

- Effective negotiation occurs when both substance goals (dealing with outcomes) and relationship goals (dealing with processes) are achieved.

- Ethical problems in negotiation can arise when people become manipulative and dishonest in trying to satisfy their self-interests at any cost.

What are alternative strategies for negotiation?

- The distributive approach to negotiation emphasizes win-lose outcomes; the integrative or principled approach to negotiation emphasizes win-win outcomes.

- In distributive negotiation, the focus of each party is on staking out positions in the attempt to claim desired portions of a fixed “pie.”

- In integrative negotiation, sometimes called principled negotiation, the focus is on determining the merits of the issues and finding ways to satisfy one another's needs.

- The success of negotiations often depends on avoiding common pitfalls such as the myth of the fixed pie, escalating commitment, overconfidence, and both the telling and hearing problems.

- When negotiations are at an impasse, third-party approaches such as mediation and arbitration offer alternative and structured ways for dispute resolution.

Terms to Know

Accommodation (or smoothing) (p. 223)

Arbitration (p. 230)

Authoritative command (p. 223)

Avoidance (p. 223)

Bargaining zone (p. 227)

Collaboration and problem solving (p. 223)

Competition (p. 223)

Compromise (p. 223)

Conflict (p. 214)

Conflict resolution (p. 218)

Distributive negotiation (p. 226)

Dysfunctional conflict (p. 216)

Effective negotiation (p. 224)

Emotional conflict (p. 214)

Functional conflict (p. 216)

Integrative negotiation (p. 226)

Intergroup conflict (p. 215)

Interorganizational conflict (p. 215)

Interpersonal conflict (p. 214)

Intrapersonal conflict (p. 215)

Mediation (p. 230)

Negotiation (p. 224)

Substantive conflict (p. 214)

Self-Test 10

Multiple Choice

Multiple Choice

- A/an __________ conflict occurs in the form of a fundamental disagreement over ends or goals and the means for accomplishment.

- (a) relationship

- (b) emotional

- (c) substantive

- (d) procedural

- The indirect conflict management approach that uses the chain of command for conflict resolution is known as_________.

- (a) upward referral

- (b) avoidance

- (c) smoothing

- (d) appeal to common goals

- Conflict that ends up being “functional” for the people and organization involved would most likely be__________.

- (a) of high intensity

- (b) of moderate intensity

- (c) of low intensity

- (d) nonexistent

- One of the problems with the suppression of conflicts is that it__________.

- (a) creates winners and losers

- (b) is a temporary solution that sets the stage for future conflict

- (c) works only with emotional conflicts

- (d) works only with substantive conflicts

- When a manager asks people in conflict to remember the mission and purpose of the organization and to try to reconcile their differences in that context, she is using a conflict management approach known as__________.

- (a) reduced interdependence

- (b) buffering

- (c) resource expansion

- (d) appeal to common goals

- An__________conflict occurs when a person must choose between two equally attractive alternative courses of action.

- (a) approach-avoidance

- (b) avoidance-avoidance

- (c) approach-approach

- (d) avoidance-approach

- If two units or teams in an organization are engaged in almost continual conflict and the higher manager decides it is time to deal with matters through managed interdependence, which is a possible choice of conflict management approach?

- (a) compromise

- (b) buffering

- (c) appeal to common goals

- (d) upward referral

- A lose-lose conflict is likely when the conflict management approach is one of ________.

- (a) collaborator

- (b) altering scripts

- (c) accommodation

- (d) problem solving

- Which approach to conflict management can be best described as both highly cooperative and highly assertive?

- (a) competition

- (b) compromise

- (c) accommodation

- (d) collaboration

- Both __________ goals should be considered in any negotiation.

- (a) performance and evaluation

- (b) task and substance

- (c) substance and relationship

- (d) task and performance

- The three criteria for effective negotiation are__________.

- (a) harmony, efficiency, and quality

- (b) quality, efficiency, and effectiveness

- (c) ethical behavior, practicality, and cost-effectiveness

- (d) quality, practicality, and productivity

- Of the following statements, only __________ is true.

- (a) Principled negotiation leads to accommodation.

- (b) Hard distributive negotiation leads to collaboration.

- (c) Soft distributive negotiation leads to accommodation or compromise.

- (d) Hard distributive negotiation leads to win-win conflicts.

- Another name for integrative negotiation is__________.

- (a) arbitration

- (b) mediation

- (c) principled negotiation

- (d) smoothing

- When a person approaches a negotiation with the assumption that in order for him to gain his way, the other party must lose or give up something, the ____________ negotiation pitfall is being exhibited.

- (a) myth of the fixed pie

- (b) escalating commitment

- (c) overconfidence

- (d) hearing problem

- In the process of alternative dispute resolution known as__________, a neutral third party acts as a judge to determine how a conflict will be resolved.

- (a) mediation

- (b) arbitration

- (c) conciliation

- (d) collaboration

Short Response

Short Response

16. List and discuss three conflict situations faced by managers.

17. List and discuss the major indirect conflict management approaches.

18. Under what conditions might a manager use avoidance or accommodation?

19. Compare and contrast distributive and integrative negotiation. Which is more desirable? Why?

Applications Essay

Applications Essay

20. Discuss the common pitfalls you would expect to encounter in negotiating your salary for your first job, and explain how you would best try to deal with them.

Steps to Further Learning 10

Top Choices from The OB Skills Workbook

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook found at the back of the book are suggested for Chapter 10.

“This puts me smack in the middle of a distinctively modern dilemma: how to handle the tensions of a marriage between an alpha woman and a beta man?”

“This puts me smack in the middle of a distinctively modern dilemma: how to handle the tensions of a marriage between an alpha woman and a beta man?”