11

Communication

How well do you communicate? Many people think they are effective communicators, but evidence suggests otherwise. In this chapter we identify the challenges of communication in organizational contexts, and describe what we can do to become more skilled communicators. ![]()

What's Inside?

![]() Bringing OB to LIFE

Bringing OB to LIFE

REMOVING DOUBTS BY EMBRACING OPEN INFORMATION

![]() Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

EVERYONE ON THE TEAM SEEMS REALLY HAPPY. IS IT TIME TO CREATE SOME DISHARMONY?

![]() Checking Ethics in OB

Checking Ethics in OB

PRIVACY IN THE AGE OF SOCIAL NETWORKING

![]() Finding the Leader in You

Finding the Leader in You

IDEO SELECTS FOR COLLABORATIVE LEADERS

![]() OB in Popular Culture

OB in Popular Culture

CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION AND THE AMAZING RACE

![]() Research Insight

Research Insight

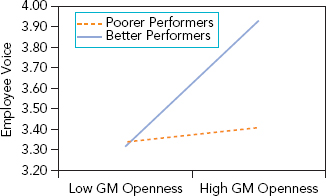

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND EMPLOYEE VOICE: IS THE DOOR REALLY OPEN?

Chapter at a Glance

- What Is Communication?

- What Are Barriers to Effective Communication?

- What Is the Nature of Communication in Organizational Contexts?

- What Is the Nature of Communication in Relational Contexts?

- Why Is Feedback So Important?

The Nature of Communication

![]() THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNICATION

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNICATION

THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS ![]() NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Communication is the lifeblood of the organization. All organizational behavior—good and bad—stems from communication. Yet, despite the fact that we spend most of our lives communicating, we are not always very good at it.

In this chapter we examine communication in organizational and relational contexts to identify factors associated with effective and ineffective communication. A basic premise of this chapter is that to communicate effectively we need to have good relationships, and to have good relationships we need to communicate effectively.

Importance of Communication

Importance of Communication

Communication has always been important, but the nature of communication is changing in organizations and in the world. Widely available information is empowering people and societies in unprecedented ways. For example, the Egyptian Revolution of 2012 was called the “Facebook Revolution” because Egyptian citizens used Facebook to organize a revolution behind the scenes. In organizations, managers are not able to control information like they once could, and this is changing the nature of power in organizations. When Yahoo! announced that it would no longer allow employees to work at home, employees rebelled by anonymously posting company memos online. What managers had intended to be private company policy quickly snowballed into a major international news story and critique.

Communication is the glue that holds organizations together. It is the way we share information, ideas, and expectations as well as display emotions to coordinate action. Therefore we need to make effective communication a top priority in organizations.

The Communication Process

The Communication Process

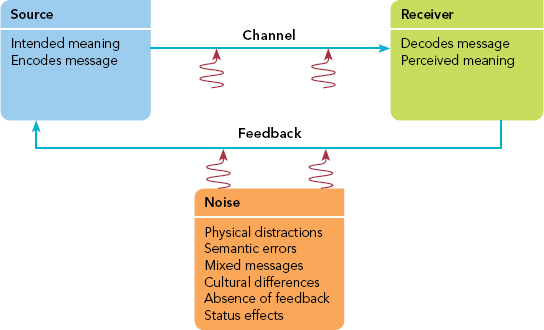

Although we all know what communication is, it is useful to review the basic communication model to set up a discussion of how and why communication breakdowns occur. As illustrated in Figure 11.1, communication is a process of sending and receiving messages with attached meanings. The key elements in the communication process include a source, which encodes an intended meaning into a message, and a receiver, which decodes the message into a perceived meaning. The receiver may or may not give feedback to the source.

Communication is the process of sending and receiving symbols with attached meanings.

FIGURE 11.1 The communication process.

The information source, or sender, is a person or group trying to communicate with someone else. The source seeks to communicate, in part, to change the attitudes, knowledge, or behavior of the receiver. A team leader, for example, may want to communicate with a division manager in order to explain why the team needs more time or resources to finish an assigned project. This involves encoding—the process of translating an idea or thought into a message consisting of verbal, written, or nonverbal symbols (such as gestures), or some combination of these. Messages are transmitted through various communication channels, such as face-to-face meetings, e-mail, texts, videoconferencing, Skype, blogs, and newsletters. The choice of channel can have an important impact on the communication process. Some people are better at particular channels, and certain channels are better able to handle some types of messages. In the case of the team leader communicating with the division manager, for example, it can make quite a difference whether the message is delivered in person or electronically.

The sender is a person or group trying to communicate with someone else.

Encoding is the process of translating an idea or thought into a message consisting of verbal, written, or nonverbal symbols (such as gestures), or some combination of them.

Communication channels are the pathways through which messages are communicated.

The communication process is not complete even though a message is sent. The receiver is the individual or group of individuals to whom a message is directed. In order for meaning to be assigned to any received message, its contents must be interpreted through decoding. This process of translation is complicated by many factors, including the knowledge and experience of the receiver and his or her relationship with the sender. A message may also be interpreted with the added influence of other points of view, such as those offered by co-workers, colleagues, or family members. Problems can occur in receiving when the decoding results in the message being interpreted differently from what was originally intended.

The receiver is the individual or group of individuals to whom a message is directed.

Feedback is the process through which the receiver communicates with the sender by returning another message. Feedback represents two-way communication, going from sender to receiver and back again. Compared to one-way communication, which flows from sender to receiver only, two-way communication is more accurate and effective, although it may also be more costly and time consuming. Because of their efficiency, oneway forms of communication—mass e-mails, reports, newsletters, division-wide meetings, and the like—are frequently used in work settings. Although one-way messages are easy for the sender, they might be more time consuming in the long run when receivers are unsure what the sender means or wants done.

Feedback communicates how one feels about something that another person has done or said.

Although this process appears to be elementary, it is not as simple as it looks. Many factors can inhibit effective transmission of a message. One of these is noise. Noise is the term used to describe any disturbance that disrupts communication and interferes with the transference of messages within the communication process. If your stomach is growling because your class is right before lunch, or if you are worried about an exam later in the day, it can interfere with your ability to pay attention to what your professor and classmates are saying. In addition, if you don't like a person, your emotions may trigger a “voice” in your head that you can't turn off, disrupting your ability to hear and listen effectively. These are all noise in the communication process.

Noise is anything that interferes with the effectiveness of communication.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is communication through means other than words. The most common forms are facial expressions, body position, eye contact, and other physical gestures. Studies show that when verbal and nonverbal communication do not match, receivers pay more attention to the nonverbal. This is because the nonverbal side of communication often holds the key to what someone is really thinking or meaning. Do you know how to tell if someone is lying? Watch for avoidance of eye contact and signs of stress, such as fidgeting, sweating, and, in more serious cases, dilated pupils.

Nonverbal communication occurs through facial expression, body motions, eye contact, and other physical gestures.

Nonverbal communication affects the impressions we make on others. Because of this, we should pay careful attention to both verbal and nonverbal aspects of our communication, including dress, timeliness, and demeanor. It is well known that interviewers tend to respond more favorably to job candidates whose nonverbal cues are positive, such as eye contact and erect posture, than to those displaying negative nonverbal cues, such as looking down or slouching. The way we choose to design or arrange physical space also has powerful effects on how we interpret one another.1 This can be seen in choice of workspace designs, such as that found in various office layouts or buildings. Figure 11.2 shows three different office arrangements and the messages they may communicate to visitors. Check the diagrams against the furniture arrangement in your office or that of your instructor or a person with whom you are familiar. What are you or they saying to visitors by the choice of furniture placement?2

FIGURE 11.2 Furniture placement and nonverbal communication in the office.

Because nonverbal communication is so powerful, those who are more effective at communication are careful to use it to their advantage. For some, this means recognizing the importance of presence, or the act of speaking without using words. Analysis of Adolf Hitler's speeches shows he was a master at managing presence. Hitler knew how to use silence to great effect. He would stand in front of large audiences in complete silence for several minutes, all the while in total command of the room. Steve Jobs of Apple used the same technique during product demonstrations. In fact, Jobs was so good at managing presence that it made it more difficult for his successor, Tim Cook, who pales in comparison.

Presence is the act of speaking without using words.

Communication Barriers

![]() INTERPERSONAL BARRIERS

INTERPERSONAL BARRIERS ![]() PHYSICAL BARRIERS

PHYSICAL BARRIERS

SEMANTIC BARRIERS ![]() CULTURAL BARRIERS

CULTURAL BARRIERS

In interpersonal communication, it is important to understand the barriers that can easily create communication problems. The most common barriers in the workplace include interpersonal issues, physical distractions, meaning (or “semantic”) barriers, and cultural barriers.

Interpersonal Barriers

Interpersonal Barriers

Interpersonal barriers occur when individuals are not able to objectively listen to the sender due to things such as lack of trust, personality clashes, a bad reputation, or stereotypes/prejudices. Interpersonal barriers are reflected in a quote paraphrased from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “I can't hear what you say because who you are rings so loudly in my ears.” When strong, interpersonal barriers are present, receivers and senders often distort communication by evaluating and judging a message or failing to communicate it effectively. Think of how you communicate with someone you don't like, or a co-worker or a classmate who rubs you the wrong way. Do you listen effectively, or do you ignore them? Do you share information, or do you keep your interactions short, and perhaps even evasive?

Interpersonal barriers occur when individuals are not able to objectively listen due to personality issues.

Such problems are indicative of selective listening and filtering. In selective listening, individuals block out information or only hear things that match preconceived notions. Someone who does not trust will assume that the other is not telling the truth, or may “hear” things in the communication that are not accurate. An employee who believes a co-worker is incompetent may disregard important information if it comes from that person. Individuals may also filter information by conveying only some of the information. If we don't like a co-worker, we may decide to leave out critical details or pointers that would help him or her to be more successful in getting things done.

Selective listening involves blocking out information and only hearing things that the listener wants to hear.

Filtering leaves out critical details.

Another major problem in interpersonal communication is avoidance. Avoidance occurs when individuals choose to ignore or deny a problem or issue, rather than confront it. It is a major barrier to openness and honesty in communication. Avoidance occurs because individuals fear the conversation will be uncomfortable, or worry that trying to talk about the problem will only make it worse. This fear often comes with a lack of understanding about how to approach difficult conversations. Avoidance can be overcome by learning to use supportive communication principles, as described in a later section.

Avoidance occurs when individuals ignore or deny a problem rather than confront it.

Physical Barriers

Physical Barriers

Physical distractions are another barrier that can interfere with the effectiveness of a communication attempt. Some of these distractions are evident in the following conversation between an employee, George, and his manager.3

Physical distractions include interruptions from noises, visitors, and the like, that interfere with communication.

Okay, George, let's hear your problem (phone rings, boss picks it up, promises to deliver the report “just as soon as I can get it done”). Uh, now, where were we—oh, you're having a problem with marketing. So (the manager's secretary brings in some papers that need immediate signatures; he scribbles his name and the secretary leaves) . . . you say they're not cooperative? I tell you what, George, why don't you (phone rings again, lunch partner drops by) . . . uh, take a stab at handling it yourself. I've got to go now.

Besides what may have been poor intentions in the first place, George's manager allowed physical distractions to create information overload. As a result, the communication with George suffered. Setting priorities and planning can eliminate this mistake. If George has something to say, his manager should set aside adequate time for the meeting. In addition, interruptions such as telephone calls, drop-in visitors, and the like should be prevented. At a minimum, George's manager could start by closing the door to the office and instructing his secretary not to disturb them.

Semantic Barriers

Semantic Barriers

Semantic barriers involve a poor choice or use of words and mixed messages. When in doubt regarding the clarity of your written or spoken messages, the popular KISS principle of communication is always worth remembering: “Keep it short and simple.” Of course, that is often easier said than done. The following illustrations of the “bafflegab” that once tried to pass as actual “executive communication” are a case in point.4

Semantic barriers involve a poor choice or use of words and mixed messages.

- A. “We solicit any recommendations that you wish to make, and you may be assured that any such recommendations will be given our careful consideration.”

- B. “Consumer elements are continuing to stress the fundamental necessity of a stabilization of the price structure at a lower level than exists at the present time.”

One has to wonder why these messages weren't stated more understandably: (A) “Send us your recommendations; they will be carefully considered.” (B) “Consumers want lower prices.”

Cultural Barriers

Cultural Barriers

We all know that globalization is here to stay. What we might not realize is that the success of international business often rests with the quality of cross-cultural communication. A common problem in cross-cultural communication is ethnocentrism, the tendency to believe one's culture and its values are superior to those of others. It is often accompanied by an unwillingness to try to understand alternative points of view and to take the values they represent seriously. Another problem in cross-cultural communication arises from parochialism—assuming that the ways of your culture are the only ways of doing things. It is parochial for traveling American businesspeople to insist that all of their business contacts speak English, whereas it is ethnocentric for them to think that anyone who dines with a spoon rather than a knife and fork lacks proper table manners.

Ethnocentrism is the tendency to believe one's culture and its values are superior to those of others.

Parochialism assumes that the ways of your culture are the only ways of doing things.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

The difficulties with cross-cultural communication are perhaps most obvious in respect to language differences. Advertising messages, for example, may work well in one country but not when translated into the language of another. Problems accompanied the introduction of Ford's European small car model, the “Ka” into Japan (in Japanese, ka means “mosquito”). Gestures may also be used quite differently in the various cultures of the world. For example, crossed legs are quite acceptable in the United Kingdom but are rude in Saudi Arabia if the sole of the foot is directed toward someone. Pointing at someone to get his or her attention may be acceptable in Canada, but in Asia it is considered inappropriate and even offensive.5

The role of language in cross-cultural communication has additional and sometimes even more subtle sides. The anthropologist Edward T. Hall notes important differences in the ways different cultures use language, and he suggests that these differences often cause misunderstanding.6 Members of low-context cultures are very explicit in using the spoken and written word. In these cultures, such as those of Australia, Canada, and the United States, the message is largely conveyed by the words someone uses, and not particularly by the context in which they are spoken. In contrast, members of high-context cultures use words to convey only a limited part of the message. The rest must be inferred or interpreted from the context, which includes body language, the physical setting, and past relationships—all of which add meaning to what is being said. Many Asian and Middle Eastern cultures are considered high context, according to Hall, whereas most Western cultures are low context.

In low-context cultures, messages are expressed mainly by the spoken and written word.

In high-context cultures, words convey only part of a message, while the rest of the message must be inferred from body language and additional contextual cues.

International business experts advise that one of the best ways to gain understanding of cultural differences is to learn at least some of the language of the country with which one is dealing. Says one global manager : “Speaking and understanding the local language gives you more insight; you can avoid misunderstandings.” A former American member of the board of a German multinational says: “Language proficiency gives a [non-German] board member a better grasp of what is going on . . . not just the facts and figures but also texture and nuance.”7 Although the prospect of learning another language may sound daunting, there is little doubt that it can be well worth the effort.

Communication in Organizational Contexts

![]() COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

COMMUNICATION CHANNELS ![]() COMMUNICATION FLOWS

COMMUNICATION FLOWS

VOICE AND SILENCE

Communication Channels

Communication Channels

Organizations are designed based on bureaucratic organizing principles; that is, jobs are arranged in hierarchical fashion with specified job descriptions and formal reporting relationships. However, much information in organizations is also passed along more spontaneously through informal communication networks. These illustrate two types of information flows in organizations: formal and informal communication channels.

Formal channels follow the chain of command established by an organization's hierarchy of authority. For example, an organization chart indicates the proper routing for official messages passing from one level or part of the hierarchy to another. Because formal channels are recognized as authoritative, it is typical for communication of policies, procedures, and other official announcements to adhere to them. On the other hand, much “networking” takes place through the use of informal channels that do not adhere to the organization's hierarchy of authority. They coexist with the formal channels but frequently diverge from them by skipping levels in the hierarchy or cutting across divisional lines. Informal channels help to create open communications in organizations and ensure that the right people are in contact with one another.

Formal channels follow the official chain of command.

Informal channels do not follow the chain of command.

FIGURE 11.3 Richness of communication channels.

A common informal communication channel is the grapevine, or network of friendships and acquaintances through which rumors and other unofficial information are passed from person to person. Grapevines have the advantage of being able to transmit information quickly and efficiently. They also help fulfill the needs of people involved in them. Being part of a grapevine can provide a sense of security that comes from “being in the know” when important things are going on. It also provides social satisfaction as information is exchanged interpersonally. The primary disadvantage of grapevines arises when they transmit incorrect or untimely information. Rumors can be very dysfunctional, both to people and to organizations. One of the best ways to avoid rumors is to make sure that key persons in a grapevine get the right information from the start.

A grapevine transfers information through networks of friendships and acquaintances.

Channel richness indicates the capacity of a channel to convey information. And as indicated in Figure 11.3, the richest channels are face to face. Next are telephone, videoconferences and text, followed by e-mail, reports, and letters. The leanest channels are posted notices and bulletins. When messages get more complex and open ended, richer channels are necessary to achieve effective communication. Leaner channels work well for more routine and straightforward messages, such as announcing the location of a previously scheduled meeting.

Channel richness indicates the capacity of a channel to convey information.

Communication Flows

Communication Flows

Information in organizations flows in many directions: downward, laterally, and upward. Downward communication follows the chain of command from top to bottom. Lower-level personnel need to know what higher levels are doing and be reminded of key policies, strategies, objectives, and technical developments. Of special importance are feedback and information on performance results. Sharing such information helps minimize the spread of rumors and inaccuracies regarding higher-level intentions, as well as create a sense of security and involvement among receivers who believe they know the whole story.

Downward communication follows the chain of command from top to bottom.

Lateral communication is the flow of information across the organization. The biggest barrier to lateral communication is organizational silos, units that are isolated from one another by strong departmental or divisional lines. In siloed organizations, units tend to communicate more inside than outside, and they often focus on protecting turf and information rather than sharing it. This is in direct contrast to what we need in today's organizations, which is timely and accurate information in the hands of workers.

Lateral communication is the flow of messages at the same levels across organizations.

Organizational silos are units that are isolated from one another by strong departmental or divisional lines.

Inside organizations, people must communicate across departmental or functional boundaries and listen to one another's needs as “internal customers.” More effective organizations design lateral communication into the organizational structure, in the form of cross-departmental committees, teams, or task forces as well as matrix structures. There is also growing attention to organizational ecology—the study of how building design may influence communication and productivity by improving lateral communications.

CHECKING ETHICS IN OB

The flow of messages from lower to higher organizational levels is upward communication. Upward communication keeps higher levels informed about what lower-level workers are doing and experiencing in their jobs. A key issue in upward communication is status differences. Status differences create potential communication barriers between persons of higher and lower ranks.

Upward communication is the flow of messages from lower to higher organizational levels.

Status differences are differences between persons of higher and lower ranks.

Communication is frequently biased when flowing upward in organizational hierarchies. Subordinates may filter information and tell their superiors only what they think the bosses want to hear. They do this out of fear of retribution for bringing bad news, an unwillingness to identify personal mistakes, or just a general desire to please. Regardless of the reason, the result is the same: The higher-level decision maker may end up taking the wrong actions because of biased and inaccurate information supplied from below.

This is sometimes called the mum effect, in reference to tendencies to sometimes keep “mum” from a desire to be polite and a reluctance to transmit bad news.8 One of the best ways to counteract the mum effect is to develop strong trusting relationships. Therefore, organizations that want to enhance upward communication and reduce the mum effect work hard to develop high-quality relationships and trusting work climates throughout the organization.

Voice and Silence

Voice and Silence

The choice to speak up (i.e., to confront situations) rather than remain silent is known as voice.9 Employees engage in voice when they share ideas, information, suggestions, or concerns upward in organizations. Voice is important because it helps improve decision making and promote responsiveness in dynamic business conditions. It also facilitates team performance by encouraging team members to share concerns if they think the team is missing information or headed in the wrong direction-correcting problems before they escalate.10

Voice involves speaking up to share ideas, information, suggestions or concerns upward in organizations.

Despite this, many employees choose to remain silent rather than voice.11 Silence occurs when employees have input that could be valuable but choose not to share it. Research shows that two key factors play into the choice to voice or remain silent. The first is the perceived efficacy of voice, or whether the employee believes their voice will make a difference. If perceived efficacy is low, employees will think “Why bother? No one will listen and nothing will change.”

Silence occurs when employees choose not to share input that could be valuable.

The second is perceived risk. Employees will be less likely to voice if they believe speaking up to authority will damage their credibility and/or relationships. Consistent with the mum effect, many employees deliberately withhold information from those in positions of power because they fear negative consequences, such as bad performance evaluations, undesirable job assignments, or even being fired.

Employees are more likely to remain silent in hierarchical or bureaucratic structures, and when they work in a fear climate. Therefore, organizations should create environments that are open and supportive. Formal structural channels for employees to provide information, such as hotlines, grievance procedures, and suggestion systems, are also helpful.

Communication in Relational Contexts

![]() RELATIONSHIP DEVELOPMENT

RELATIONSHIP DEVELOPMENT ![]() RELATIONSHIP MAINTENANCE

RELATIONSHIP MAINTENANCE

SUPPORTIVE COMMUNICATION PRINCIPLES ![]() ACTIVE LISTENING

ACTIVE LISTENING

Much of the work that gets done in organizations occurs through relationships. Surprisingly, although we live our lives in relationships, most of us are not aware of, or ever taught, how to develop good-quality relationships. Many times people think relationships just happen. When relationships develop poorly, we have a tendency to blame the other: “There is something wrong with the other person” or “They are just impossible to deal with.” But relationships are much more manageable than we might think . . . it comes down to how we communicate in relational contexts.

Relationship Development

Relationship Development

Relationships develop through a relational testing process. This begins when one person makes a disclosure—an opening up or revelation about oneself—to another. For example, a simple disclosure is sharing one's likes or dislikes with another.

Relational testing is a process through which individuals make disclosures and form opinions or attributions about the other based on the disclosures.

A disclosure is an opening up or revelation to another of something about oneself.

Once a disclosure is made, the other automatically begins to form a judgment. If the other shares the like or dislike, the individuals experience a sense of bonding, or attachment, with one another. If the other does not share the likes or dislikes, a positive connection is not felt and the relationship may remain at arm's length.

A deeper disclosure is a more intensely personal revelation, such as an intimate detail about one's personal history. Deeper disclosures are typically appropriate only in very high-quality relationships in which individuals know and trust one another. Inappropriate disclosures made too early in exchanges can derail the process and result in ineffective relationship development.

This sequential process represents the active “scorekeeping” stage of the testing process. If a test is passed, the relationship progresses, and disclosures may become more revealing. If a test is failed, individuals begin to hold back, and interactions may even take on a negative tone. This process is much like the classic game of Chutes and Ladders (see Figure 11.4). When relational tests go well they can act like “ladders,” escalating the relationship to higher levels. When relational violations occur they can act like “chutes,” dropping the relationship back down to lower levels.

Relational testing is really easy to see in the context of going out with someone. When you first hang out you share information with the other and watch for a reaction; you also listen for what the other shares with you. When things go well, you “hit it off” and things flow smoothly—you enjoy the interaction, and you like what the other person has to say. This leads you to share more information. When things go poorly, tests are not being passed for at least one individual and the interactions can become awkward and uncomfortable.

Because we are taught to be polite, sometimes it can be hard to tell how things are really going if individuals are covering up their true feelings or reactions. In professional settings, we engage in testing without even thinking about it. We don't do it on purpose—it's a natural part of how humans interact. Oftentimes, opinions get formed on a very trivial or limited information.

FIGURE 11.4 Relational Testing Process.

The key point is to understand that testing processes are going on around us all of the time, and if you want to more carefully manage your relationships, you need to be more consciously aware of when and how testing is occurring. When it is happening, you have to pay attention so you can manage the process more effectively. This does not mean being dishonest or fake; in fact, being fake is a quick way to fail a test! It does mean being careful how you engage with others with whom you have not yet established a relationship (e.g., a new boss).

Relationship Maintenance

Relationship Maintenance

Once relationships are established, testing processes take on a different form. They go from active testing to watching for relational violations.12 A relational violation is a violation of the “boundary” of acceptable behavior in a relationship. These boundaries will vary depending on the nature of the relationship. In marriage, infidelity is a boundary violation. In a high-quality manager-subordinate relationship, breaking trust is a boundary violation. In a poor-quality manager-subordinate relationship, it may take more serious offense, such as sabotage or a work screwup, to constitute a boundary violation. The point is that the testing process is now not active “scorekeeping,” or evaluating nearly every interaction, but rather one of noticing testing only when the relationship has been violated.13

A relational violation is a violation of the “boundary” of acceptable behavior in a relationship.

As long as violations don't occur, individuals interact in the context of the relational boundaries, and the relationship proceeds just fine. When violations do occur, however, testing kicks back. If the relationship survives the violation—and some don't—it is now at a lower quality, or even in a negative state. For it to recover, it must go through relational repair.

Relational repair involves actions to return the relationship to a positive state. Relational repair is again a testing process, but this time the intention is to rebuild or reestablish the relationship quality. For example, a violation of trust can be repaired with a sincere apology, followed by actions demonstrating trustworthiness. A violation of professional respect can be repaired with strong displays of professional competence.

Relational repair involves actions to return the relationship to a positive state.

In most cases, relational repair requires effective communication. As you can imagine, not everyone has these skills, and those who have them often use them intuitively—not quite aware of what they are doing. One set of principles that can help individuals engage in relational repair, as well as in relationships, is supportive communication principles.

Supportive Communication Principles

Supportive Communication Principles

Supportive communication principles focus on joint problem solving. They are especially effective in dealing with relational breakdowns or in addressing problematic behaviors before they escalate into relational violations.14

Supportive communication principles are a set of tools focused on joint problem solving.

Supportive communication principles help us avoid problems of defensiveness and disconfirmation in interpersonal communication. We all know these problems. You feel defensive when you think you are being attacked and need to protect yourself. Signs of defensiveness are people beginning to get angry or aggressive in a communication, or lashing out. You have a feeling of disconfirmation when you sense that you are being put down and your self-worth is being questioned. When people are discon-firmed they withdraw from a conversation or engage in show-off behaviors to try to build themselves back up.

Defensiveness occurs when individuals feel they are being attacked and need to protect themselves.

Disconfirmation occurs when an individual feels his or her self-worth is being questioned.

Relationships under stress are particularly susceptible to problems of defensiveness and disconfirmation. Therefore, in situations of relational repair it is doubly important to watch for and diffuse defensiveness and disconfirmation by stopping and refocusing the conversation as soon as these problems begin to appear.

The first, and most important, technique to consider in supportive communication is to focus on the problem and not the person. If you focus on the person, the most likely reaction is for the other to become defensive or disconfirmed. A trick many people use to remember this is “I” statements rather than “you” statements. “You” statements are like finger pointing: “You screwed up the order I sent you” or “You undermined me in the meeting.” An “I” statement, and a focus on the problem, would be “I had a problem with my order the other day and would like to talk with you about what went wrong with it” or “I felt undermined in the meeting the other day when I was interrupted in the middle of my presentation and not able to continue.”

The second technique is to focus on a problem that the two of you can do something about. Remember that the focus should be on joint problem solving. This means the framing of the message should be on a shared problem, and the tone should be on how you can work together to fix it and both benefit in the process. It helps in this part of the conversation if you can make it clear to the other person how you care about him or her or the relationship and that the other person trusts your motives. If another perceives that you are out for yourself or out to attack, the conversation will break down. For example, “I'd like to talk with you about how we can manage the budget more effectively so we can avoid problems in the future” rather than “You overspent on the budget and now I have to fix your mess.”

Beyond this, the other techniques help you think about the kinds of words you should choose to make the conversation more effective. For example, you should be specific/not global, and objective/not judgmental. Specific/not global means not using words like never or always. These words are easy to argue, and you will quickly find the other person saying “It's not true.” Try to be more factual and objective. Instead of saying “You never listen to me,” say “The other day in the meeting you interrupted me three times and that made it hard for me to get my point across.”

The principles also tell you to own the communication and make sure to be congruent. Owning the communication means you take responsibility for what you say rather than place it on a third party. A manager who says, “Corporate tells us we need to better document our work hours,” sends a weaker message than one who says, “I believe that better documenting our work hours will help us be more effective in running our business.” Being congruent means matching the words (verbal) and the body language (nonverbal). If your words say, “No, I'm not mad,” but your body language conveys anger, then you are not being honest or forthright. The other person will know it, and this may cause him or her to be less open and committed to the conversation in return.

Active Listening

Active Listening

Supportive communication principles emphasize the importance of active listening. Active listening again focuses on problem solving, but this time from the standpoint of trying to help another person. For example, active listening is often used in counseling situations. In these situations, your intent is to help the other person sort through problems involving emotions, attitudes, motivation, personality issues, and so on. To do this effectively, you need to keep the focus on the counselee and his or her issue(s) and not you and your issue(s).

Active listening involves listening to another person with the purpose of helping a person think through his or her problem.

The biggest mistake people make in this kind of listening is jumping to advice too early or changing the focus of the conversation onto themselves. A good principle to keep in mind during active listening is “We have two ears and one mouth, so we should listen twice as much as we speak.”15 When you are engaged in active listening, your goal is to keep the focus on the other person, and to help that other person engage in effective self-reflection and problem solving.

Active listening involves understanding the various types of listening responses and matching your response to the situation. What is most important to remember is that to counsel someone, you want to use reflecting and probing more often than advising or deflecting. Reflecting and probing are “opening” types of responses that encourage others to elaborate and process. Advising and deflecting are “closed” types of responses and should only be used sparingly, and at the end of the conversation rather than the beginning.16

Reflecting means paraphrasing back what the other said. Reflecting can also mean summarizing what was said or taking a step further by asking a question for clarification or elaboration. Reflecting allows us to show we are really listening and to give the speaker a chance to correct any misunderstanding we may have. Probing means asking for additional information. In probing you want to be careful about the kinds of questions you ask so you do not come across as judgmental (e.g., “How could you have done that?”). You also don't want to change the subject before the current subject is resolved. Effective probing flows from what was previously said, and asks for elaboration, clarification, and repetition if needed.

Reflecting: paraphrasing back what the speaker said, summarizing what was said, or taking a step further by asking a question for clarification or elaboration.

Probing: asking for additional information that helps elaborate, clarify, or repeat if necessary.

Deflecting means shifting to another topic. When we deflect to another topic we risk coming across as uninterested in what is being said or being too preoccupied to listen. Many of us unwittingly deflect by sharing our own personal experiences. While we think this is being helpful in letting the speaker know he or she is not alone, it can be ineffective if it diverts the conversation to us and not them. The best listeners keep deflecting to a minimum.17

Deflecting is shifting the conversation to another topic.

Advising means telling someone what to do. This is a closed response, because once you tell someone what to do that typically can end a conversation. While we think we are helping others by advising them, we actually may be hurting because doing so can communicate a position of superiority rather than mutuality. Again, the best listeners work to control their desire to advise unless specifically asked to do so and to deliver the advice in the context of supportiveness rather than presumptuousness.

Advising is telling someone what to do.

Developmental Feedback

![]() FEEDBACK GIVING

FEEDBACK GIVING ![]() FEEDBACK SEEKING

FEEDBACK SEEKING ![]() FEEDBACK ORIENTATION

FEEDBACK ORIENTATION

In most workplaces, there is too little feedback rather than too much. This is particularly the case for negative feedback. People avoid giving unpleasant feedback because they fear heightening emotions in the other that they will not know how to handle. For example, words intended to be polite and helpful can easily be interpreted as unpleasant and hostile. This risk is especially evident in the performance appraisal process. To serve a person's developmental needs, feedback—both the praise and the criticism-must be well communicated.

Feedback Giving

Feedback Giving

Feedback is vital for human development. Therefore, giving another person honest and developmental feedback in a sensitive and caring way is critically important. It lets us know what we are doing well and not so well, and what we can do to improve.

Developmental feedback is giving feedback in an honest and constructive way that helps another to improve.

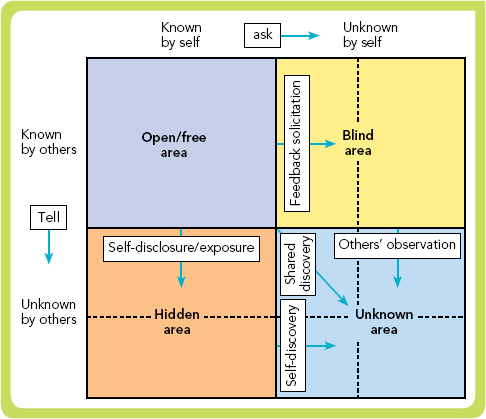

One tool that helps us understand this is the Johari Window (see Figure 11.5). The Johari Window shows us that we know some things about ourselves that others know (“open”) and some things about ourselves that others don't know (“hidden”). But there are also some things about ourselves that we don't know but others do—this is our blind spot. The blind spot is blind to us but not to others. As you can imagine, this is a problem because it means others are aware of something about us, but we are in the dark! The only way to reduce blind spots is through feedback from others—which is why feedback is so important. It helps us reduce our blind spots.

The Johari Window is a tool that helps people understand their relationship with self and others.

Despite this, giving feedback is perhaps one of the most avoided activities in organizations. It doesn't have to be, however. When delivered properly, giving feedback can be a rewarding experience. It helps build relationships and strengthens trust. As with supportive communication principles, you should keep in mind certain important techniques when giving feedback:18

- Make sure it is developmental: Be positive and focus on improvement.

- Be timely: Provide feedback soon after the issue occurs so it is fresh in mind.

- Prepare ahead of time: Be clear about what you want to say so you stick to the issue.

- Be specific: Don't use generalities, as that will just leave them wondering.

- Do it in private: Have the discussion in a safe and comfortable place for the other.

- Limit the focus: Stick to a behavior the person can do something about.

- Reinforce: Don't bring the person down-make sure he or she knows there are good things about them too.

- Show caring: Convey a sense of caring and that you are trying to help.

FIGURE 11.5 The Johari Window.

Feedback Seeking

Feedback Seeking

The Johari Window implies we should not only give feedback—we should also seek it. Pursuing feedback allows us to learn more about ourselves and how others perceive us. Feedback seeking is seeking In organizations, people engage in feedback seeking for multiple reasons: (1) to gather information for increasing performance, (2) to learn what others think about them, and (3) to regulate one's behavior.19

Feedback seeking is seeking feedback about yourself from others.

Because feedback can be emotionally charged, people typically like to see feedback involving favorable information. But this is not always the case. If individuals are more self-confident, they are more willing to seek feedback regarding performance issues, even if that feedback may be bad. The premise is that people prefer to know what they are doing wrong than perform poorly on a task. This seems to be less the case the longer that employees are in a job. Research shows that feedback seeking is lower for those who have been in a job longer, even though these employees find feedback just as valuable as newer employees do. This may be due to employees feeling they should be able to assess their own performance without needing to ask.20

When individuals fear that performance feedback will hurt their image, they are more likely to forego feedback seeking and therefore won't gain the benefits it can provide. Safe environments, where employees can trust others and there is little risk to their image or ego, can help overcome avoidance.21

Feedback Orientation

Feedback Orientation

A concept that can help us understand individual differences in how people receive feedback is feedback orientation. Feedback orientation describes one's overall receptivity to feedback. Those with a higher feedback orientation are better able to control and overcome their emotional reactions to feedback. They also process feedback more meaningfully by avoiding common attribution errors such as externalizing blame. This helps them to successfully apply feedback in establishing goals that will help them improve performance.22

Feedback orientation is a person's overall receptivity to feedback.

Feedback orientation is composed of four dimensions. Utility represents the belief that feedback is useful in achieving goals or obtaining desired outcomes. Accountability is the feeling that one is accountable to act on feedback he or she receives (e.g., “It is my responsibility to utilize feedback to improve my performance”). Social awareness is consideration of others' views of oneself and being sensitive to these views. Feedback self-efficacy is an individual's perceived competence in interpreting and responding to feedback appropriately (e.g., “I feel self-assured when dealing with feedback”).23

Those with feedback orientation tend to be higher in feedback-seeking behavior and have better relationships. They also tend to receive higher performance ratings from their managers. An important role for managers, however, is enhancing climates for developmental feedback. They can do this by being accessible, encouraging feedback seeking, and consistently providing credible, high-quality feedback in a tactful manner.24

11 Study Guide

Key Questions and Answers

- Communication is the process of sending and receiving messages with attached meanings.

- The communication process involves encoding an intended meaning into a message, sending the message through a channel, and receiving and decoding the message into perceived meaning.

- Noise is anything that interferes with the communication process.

- Feedback is a return message from the original recipient back to the sender.

- To be constructive, feedback must be direct, specific, and given at an appropriate time.

- Nonverbal communication occurs through means other than the spoken word (e.g., facial expressions, body position, eye contact, and other physical gestures).

What are barriers to effective communication?

- Interpersonal barriers detract from communication because individuals are not able to listen objectively to the sender due to personal biases; they include selective listening, filtering, and avoidance.

- Physical distractions are barriers due to interruptions from noises, visitors, and so on.

- Semantic barriers involve a poor choice or use of words and mixed messages.

- Cultural barriers include parochialism and ethnocentrism, as well as differences in low-context versus high-context cultures.

What is the nature of communication in organizational contexts?

- Organizational communication is the specific process through which information moves and is exchanged within an organization.

- Communication in organizations uses a variety of formal and informal channels; the richness of the channel, or its capacity to convey information, must be adequate for the message.

- Information flows upward, downward, and laterally in organizations.

- Organizational silos inhibit lateral communication, while upward communication is inhibited by status differences.

- The choice to speak up or remain silent is known as employee voice; voice is enhanced when employees perceive high efficacy that speaking up will make a difference and low risk that they will be harmed in the process.

What is the nature of communication in relational contexts?

- The most common types of relationships in organizations are manager-subordinate relationships, co-worker relationships, peer relationships, and customer-client relationships.

- Relationships develop through a process of relational testing; individuals make disclosures and, if the disclosure is positively received, the test is passed and the relationship will advance.

- Once relationships are established, they go from relational testing to watching for relational violations; relational violations occur when behavior goes outside the boundary of acceptable behavior in the relationship.

- Relational repair involves actions to return the relationship to a positive state.

- Supportive communication tools help in developing and repairing relationships; they focus on joint problem solving while reducing defensiveness and disconfirmation.

- Active listening is designed to help another person think through a problem; it focuses on reflecting and probing more than advising and deflecting.

Why is feedback so important?

- Most workplaces have too little feedback, not too much.

- Developmental feedback is important because it lets us know what we are doing well and not so well, and what we can do to improve.

- The Johari Window reveals the nature of blind spots—things others know about us that we don't know; feedback helps individuals reduce their blind spots.

- When done properly, giving feedback can be a rewarding experience because it helps build relationships and strengthen trust.

- Feedback seeking is seeking feedback about yourself from others.

- Feedback orientation describes one's overall receptivity to feedback.

Terms to Know

Active listening (p. 250)

Advising (p. 251)

Avoidance (p. 240)

Channel richness (p. 243)

Communication (p. 236)

Communication channels (p. 237)

Defensiveness (p. 248)

Deflecting (p. 251)

Developmental feedback (p. 251)

Disclosure (p. 246)

Disconfirmation (p. 249)

Downward communication (p. 243)

Encoding (p. 237)

Ethnocentrism (p. 241)

Feedback (p. 237)

Feedback orientation (p. 253)

Feedback seeking (p. 252)

Filter (p. 240)

Formal channels (p. 242)

Grapevine (p. 243)

High-context cultures (p. 242)

Informal channels (p. 242)

Interpersonal barriers (p. 239)

Johari window (p. 251)

Lateral communication (p. 243)

Low-context cultures (p. 242)

Noise (p. 238)

Nonverbal communication (p. 238)

Organizational silos (p. 243)

Parochialism (p. 241)

Physical distractions (p. 240)

Presence (p. 239)

Probing (p. 250)

Receiver (p. 237)

Reflecting (p. 250)

Relational repair (p. 247)

Relational testing (p. 246)

Relational violation (p. 247)

Selective listening (p. 240)

Semantic barriers (p. 240)

Sender (p. 237)

Silence (p. 245)

Status differences (p. 244)

Supportive communication principles (p. 248)

Upward communication (p. 244)

Voice (p. 245)

Self-Test 11

Multiple Choice

Multiple Choice

- In communication, of the message,___________ is anything that interferes with the transference

- (a) channel

- (b) sender

- (c) receiver

- (d) noise

- When you give constructive criticism to someone, the communication will be most effective when the criticism is__________.

- (a) general and nonspecific

- (b) given when the sender feels the need

- (c) tied to things the recipient can do something about

- (d) given all at once to get everything over with

- Which communication is the best choice for sending a complex message?

- (a) face-to-face

- (b) written memorandum

- (c) e-mail

- (d) telephone call

- __________ occurs when words convey one meaning but body posture conveys something else.

- (a) Ethnocentric message

- (b) Incongruence

- (c) Semantic problem

- (d) Status effect

- Personal bias is an example of__________in the communication process.

- (a) an interpersonal barrier

- (b) a semantic barrier

- (c) physical distractions

- (d) proxemics

- Organizational silos__________communication.

- (a) inhibit

- (b) enhance

- (c) do not affect

- (d) promote

- __________ is an example of an informal channel through which information flows in an organization.

- (a) Top-down communication

- (b) The mum effect

- (c) The grapevine

- (d) Transparency

- Relationships develop through a process of_________.

- (a) feedback seeking

- (b) feedback giving

- (c) active listening

- (d) relational testing

- __________ cause a relationship to kick back into active testing processes.

- (a) Relational violations

- (b) Interpersonal barriers

- (c) Semantic barriers

- (d) Supportive communication principles

- In___________communication the sender is likely to be most comfortable, whereas in_________communication the receiver is likely to feel most informed.

- (a) two-way; one-way,

- (b) top-down; bottom-up

- (c) bottom-up; top-down

- (d) one-way; two-way

- A manager who wants to increase voice in his department should increase__________.

- (a) bureaucracy

- (b) trust

- (c) hierarchy

- (d) the grapevine

- ___________shows us why developmental feedback is so important.

- (a) The Johari Window

- (c) Active listening

- (b) Relational testing

- (d) Nonverbal communication

- If someone is confused because they don't understand the word that the other is using the communication is suffering from a__________barrier.

- (a) listening

- (b) interpersonal

- (c) semantic

- (d) cultural

- Among the rules for active listening is__________.

- (a) remain silent and communicate only nonverbally

- (b) use primarily advising and deflecting

- (c) don't let feelings become part of the process

- (d) reflect back what you think you are hearing

- The primary focus of supportive communication principles is__________.

- (a) reducing defensiveness and disconfirmation

- (b) increasing voice

- (c) reducing silence

- (d) increasing feedback orientation

Short Response

Short Response

16. Why is channel richness a useful concept for managers?

17. What is the role of informal communication channels in organizations today?

18. Why is communication between lower and higher levels sometimes filtered?

19. What is the key to using active listening effectively?

Applications Essay

Applications Essay

20. “People in this organization don't talk to one another any more. Everything is e-mail, e-mail, e-mail. If you are mad at someone, you can just say it and then hide behind your computer.” With these words, Wesley expressed his frustrations with Delta General's operations. Xiaomei echoed his concerns, responding, “I agree, but surely the managing director should be able to improve organizational communication without losing the advantages of e-mail.” As a consultant overhearing this conversation, how do you suggest the managing director respond to Xiaomei's challenge?

Steps to Further Learning 11

Top Choices from The OB Skills Workbook

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook found at the back of the book are suggested for Chapter 11.

“I know where we are. I know the bottom line and how it's going to affect the bonus I get at the end of the year.”

“I know where we are. I know the bottom line and how it's going to affect the bonus I get at the end of the year.”