7

The Nature of Teams

When teams achieve synergy they unlock member talents and rally enthusiasm for creativity and high performance. But, we all know that teamwork isn't always easy and that teams sometimes underperform. It takes special skills and commitment—from leaders and team members alike—to bring out the best that teams have to offer. ![]()

What's Inside?

![]() Bringing OB to LIFE

Bringing OB to LIFE

REMOVING THE HEADPHONES TO SHOW TEAM SPIRIT

![]() Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

Worth Considering . . . or Best Avoided?

SOFTWARE MAKES ONLINE MEETINGS EASY. IS IT TIME TO KILL FACE-TO-FACE SIT-DOWNS?

![]() Checking Ethics in OB

Checking Ethics in OB

CHEAT NOW . . . CHEAT LATER

![]() Finding the Leader in You

Finding the Leader in You

TEAMWORK LEADS NASCAR'S RACE IN THE FAST LANE

![]() OB in Popular Culture

OB in Popular Culture

SOCIAL LOAFING AND SURVIVOR

![]() Research Insight

Research Insight

MEMBERSHIP, INTERACTIONS, AND EVALUATION INFLUENCE SOCIAL LOAFING IN GROUPS

Chapter at a Glance

- What Are Teams, and How Are They Used in Organizations?

- When Is a Team Effective?

- What Are the Stages of Team Development?

- How Can We Understand Teams at Work?

Teams in Organizations

![]() TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

TEAMS AND TEAMWORK ![]() WHAT TEAMS DO

WHAT TEAMS DO

ORGANIZATIONS AS NETWORKS OF TEAMS

CROSS-FUNCTIONAL AND PROBLEM-SOLVING TEAMS

SELF-MANAGING TEAMS ![]() VIRTUAL TEAMS

VIRTUAL TEAMS

When we hear the word team, a variety of popular sports teams often comes to mind, perhaps a favorite from the college ranks or the professional leagues. For a moment, let's stick with basketball. Scene—NBA Basketball: Scholars find that both good and bad basketball teams win more games the longer the players have been together. Why? They claim it's a “teamwork effect” that creates wins because players know each other's moves and playing tendencies.1

Let's not forget that teams are important in work settings as well. And whether or not a team lives up to expectations can have a major impact on how well its customers and clients are served. Scene—Hospital Operating Room: Scholars notice that the same heart surgeons have lower death rates for similar procedures when performed in hospitals where they do more operations. They claim it's because the doctors spend more time working together with members of these surgery teams. The scholars argue it's not only the surgeon's skills that count: “The skills of the team, and of the organization, matter.”2

Teams and Teamwork

Teams and Teamwork

What is going on in the prior examples? Whereas a group of people milling around a coffee shop counter is just that—a “group” of people, teams like those in the examples are supposed to be something more—“groups +” if you will. That “+” factor is what distinguishes the successful NBA basketball teams from the also-rans and the best surgery teams from all the others.

In OB we define a team as a group of people brought together to use their complementary skills to achieve a common purpose for which they are collectively accountable.3 Real teamworks occurs when team members accept and live up to their collective accountability by actively working together so that all of their respective skills are best used to achieve team goals.4 Of course, there is a lot more to teamwork than simply assigning members to the same group, calling it a team, appointing someone as team leader, and then expecting everybody to do a great job.5 The responsibilities for building high-performance teams rest not only with the team leader, manager, or coach, but also with the team members. If you look now at the “Heads Up: Don't Forget” sidebar, you'll find a checklist of several team must-haves, the types of contributions that team members and leaders can make to help their teams achieve high performance.6

A team is a group of people holding themselves collectively accountable for using complementary skills to achieve a common purpose.

Teamwork occurs when team members live up to their collective accountability for goal accomplishment.

What Teams Do

What Teams Do

One of the first things to understand about teams in organizations is that they do many things and make many types of performance contributions. In general, we can describe them as teams that recommend things, run things, and make or do things.7

Teams that recommend things are set up to study specific problems and recommend solutions for them. These teams typically work with a target completion date and often disband once the purpose has been fulfilled. The teams include task forces, ad hoc committees, special project teams, and the like. Members of these teams must be able to learn quickly how to pool talents, work well together, and accomplish the assigned task.

Teams that run things lead organizations and their component parts. A good example is a top-management team composed of a CEO and other senior executives. Key issues addressed by top-management teams include identifying overall organizational purposes, goals, and values as well as crafting strategies and persuading others to support them.8

Teams that make or do things are work units that perform ongoing tasks such as marketing, sales, systems analysis, manufacturing, or working on special projects with assigned due dates. Members of these action teams must have good working relationships with one another, the right technologies and operating systems, and the external support needed to achieve performance effectiveness over the long term or within an assigned deadline.

Organizations as Networks of Teams

Organizations as Networks of Teams

The many formal teams found in organizations are created and officially designated to serve specific purposes. Some are permanent and appear on organization charts as departments (e.g., market research department), divisions (e.g., consumer products division), or teams (e.g., product-assembly team). Such teams can vary in size from very small departments or teams consisting of just a few people to large divisions employing 100 or more people. Other formal teams are temporary and short lived. They are created to solve specific problems or perform defined tasks and are then disbanded once the purpose has been accomplished. Examples include temporary committees and task forces.9

Formal teams are official and designated to serve a specific purpose.

Interlocking networks of formal teams create the basic structure of an organization. On the vertical dimension, the team leader at one level is a team member at the next higher level.10 On the horizontal dimension, a team member may also serve on organization-wide task forces and committees.

Organizations also have vast networks of informal groups, which emerge and coexist as a shadow to the formal structure and without any assigned purpose or official endorsement. As shown in the nearby figure, these informal groups develop through personal relationships and create their own interlocking networks within the organization. Friendship groups consist of persons who like one another. Their members tend to work together, sit together, take breaks together, and even do things together outside of the workplace. Interest groups consist of persons who share job-related interests, such as an intense desire to learn more about computers, or non work interests, such as community service, sports, or religion.

Informal groups are unofficial and emerge to serve special interests.

Although informal groups can be places where people meet to complain, spread rumors, and disagree with what is happening in the organization, they can also be quite helpful. The personal connections activated within informal networks can speed up workflows as people assist each other in ways that cut across the formal structures. They also create interpersonal relationships that can satisfy individual needs, such as by providing companionship (meeting a social need) or a sense of personal importance (meeting an ego need).

A tool known as social network analysis is used to identify the informal groups and networks of relationships that are active in an organization. The analysis typically asks people to identify co-workers who most often help them, who communicate with them regularly, and who motivate and demotivate them. When these social networks are mapped, you learn a lot about how work really gets done and who communicates most often with whom. The results often contrast markedly with the formal arrangements depicted on organization charts. And, this information can be used to redo the charts and reorganize teamwork for better performance.

Social network analysis identifies the informal structures and their embedded social relationships that are active in an organization.

Cross-Functional and Problem-Solving Teams

Cross-Functional and Problem-Solving Teams

A cross-functional team consists of people brought together from different functional departments or work units to achieve more horizontal integration and better lateral relations. Members of cross-functional teams are supposed to work together with a positive combination of functional expertise and integrative team thinking. The expected result is higher performance driven by the advantages of better information and faster decision making.

A cross-functional team consists of members from different functions or work units.

Cross-functional teams are a way of trying to beat the functional silos problem, also called the functional chimneys problem. It occurs when members of functional units stay focused on internal matters and minimize their interactions and cooperation with other functions. In this sense, the functional departments or work teams create artificial boundaries, or “silos” that discourage rather than encourage interaction with other units. The result is poor integration and poor coordination with other parts of the organization. The cross-functional team helps break down these barriers by creating a forum in which members from different functions work together as one team with a common purpose.11

The functional silos problem occurs when members of one functional team fail to interact with others from other functional teams.

Organizations also use any number of problem-solving teams, which are created temporarily to serve a specific purpose by dealing with a specific problem or opportunity. The president of a company, for example, might convene a task force to examine the possibility of implementing flexible work hours; a human resource director might bring together a committee to advise her on changes in employee benefit policies; a project team might be formed to plan and implement a new organization-wide information system.

A problem-solving team is set up to deal with a specific problem or opportunity.

The term employee involvement team applies to a wide variety of teams whose members meet regularly to collectively examine important workplace issues. They might discuss, for example, ways to enhance quality, better satisfy customers, raise productivity, and improve the quality of work life. Such employee involvement teams are supposed to mobilize the full extent of workers' know-how and experiences for continuous improvements. An example is what some organizations call a quality circle, a small team of persons who meet periodically to discuss and make proposals for ways to improve quality.12

An employee involvement team meets regularly to address workplace issues.

A quality circle team meets regularly to address quality issues.

Self-Managing Teams

Self-Managing Teams

The self-managing team is a high-involvement workgroup design that is becoming increasingly well established. Sometimes called self-directed work teams, these teams are empowered to make the decisions needed to manage themselves on a day-to-day basis.13 They basically replace traditional work units with teams whose members assume duties otherwise performed by a manager or first-line supervisor. Figure 7.1 shows that members of true self-managing teams make their own decisions about scheduling work, allocating tasks, training for job skills, evaluating performance, selecting new team members, and controlling the quality of work.

Self-managing teams are empowered to make decisions to manage themselves in day-to-day work.

Most self-managing teams include between five and fifteen members. They need to be large enough to provide a good mix of skills and resources but small enough to function efficiently. Because team members have a lot of discretion in determining work pace and in distributing tasks, multiskilling is important. This means that team members are expected to perform many different jobs—even all of the team's jobs—as needed. Pay is ideally skill based: The more skills someone masters, the higher the base pay.

In multiskilling, team members are each capable of performing many different jobs.

The expected benefits of self-managing teams include better work quality, faster response to change, reduced absenteeism and turnover, and improved work attitudes and quality of work life. As with all organizational changes, however, the shift from traditional work units to self-managing teams may encounter difficulties. It may be hard for some team members to adjust to the “self-managing” responsibilities, and higher-level managers may have problems dealing with the absence of a first-line supervisor. Given all this, self-managing teams are probably not right for all organizations, situations, and people. They have great potential, but they also require the right setting and a great deal of management support. At a minimum, the essence of any self-managing team—high involvement, participation, and empowerment—must be consistent with the values and culture of the organization.

FIGURE 7.1 Organizational and management implications of self-managing teams.

Virtual Teams

Virtual Teams

It used to be that teamwork was confined in concept and practice to those circumstances in which members could meet face to face. Information technology has changed all that. The virtual team, one whose members work together through computer mediation rather than face to face, is now common.14 Working in electronic space and free from the constraints of geographical distance, members of virtual teams do the same things members of face-to-face groups do. They share information, make decisions, and complete tasks together. And just like face-to-face teams, they have to be set up and managed well to achieve their full benefits. Some steps to successful teams are summarized in the “Don't Neglect These Steps to Successful Virtual Teams” sidebar.15

Members of virtual teams work together through computer mediation.

The potential advantages of virtual teams begin with the cost and time efficiencies of bringing together people located at some, perhaps great, distance from one another.16 The electronic rather than face-to-face environment of the virtual team can help keep things on task by focusing attention and decision making on objective issues rather than emotional considerations and distracting interpersonal problems. Discussions and information shared among team members can also be stored electronically for continuous access and historical record keeping.

The potential downsides to virtual teams are also real. Members of virtual teams may find it hard to get up to speed and work well with one another. When the computer is the go-between, relationships and interactions can be different and require special attention. The lack of face-to-face interaction limits the role of emotions and nonverbal cues in the communication process, perhaps depersonalizing relations among team members.

Team Effectiveness

![]() CRITERIA OF AN EFFECTIVE TEAM

CRITERIA OF AN EFFECTIVE TEAM ![]() SYNERGY AND TEAM BENEFITS

SYNERGY AND TEAM BENEFITS

SOCIAL FACILITATION ![]() SOCIAL LOAFING AND TEAM PROBLEMS

SOCIAL LOAFING AND TEAM PROBLEMS

There is no doubt that teams are pervasive and important in organizations. They accomplish important tasks and help members achieve satisfaction in their work. We also know from personal experiences that teams and teamwork have their difficulties; not all teams perform well, and not all team members are always satisfied. Surely you've heard the sayings “A camel is a horse put together by a committee” and “Too many cooks spoil the broth.” They raise an important question: Just what are the foundations of team effectiveness?17

Criteria of an Effective Team

Criteria of an Effective Team

Teams in all forms and types, just like individuals, should be held accountable for their performance. To do this we need to have some understanding of team effectiveness. In OB we describe an effective team as one that achieves high levels of task performance, member satisfaction, and team viability.

An effective team is one that achieves high levels of task performance, member satisfaction, and team viability.

With regard to task performance, an effective team achieves its performance goals in the standard sense of quantity, quality, and timeliness of work results. For a formal work unit such as a manufacturing team, this may mean meeting daily production targets. For a temporary team such as a new policy task force, this may involve meeting a deadline for submitting a new organizational policy to the company president.

With regard to member satisfaction, an effective team is one whose members believe that their participation and experiences are positive and meet important personal needs. They are satisfied with their team tasks, accomplishments, and interpersonal relationships. And, with regard to team viability, the members of an effective team are sufficiently satisfied to continue working well together on an ongoing basis. When one task is finished, they look forward to working on others in the future. Such a team has all-important long-term performance potential.

Synergy and Team Benefits

Synergy and Team Benefits

Effective teams offer the benefits of synergy—the creation of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Synergy works within a team, and it works across teams as their collective efforts are harnessed to serve the organization as a whole. It creates the great beauty of teams: people working together and accomplishing more through teamwork than they ever could by working alone.

Synergy is the creation of a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

The performance advantages of teams over individuals are most evident in three situations.18 First, when there is no clear “expert” for a particular task or problem, teams tend to make better judgments than does the average individual alone. Second, teams are typically more successful than individuals when problems are complex and require a division of labor and the sharing of information. Third, because they tend to make riskier decisions, teams can be more creative and innovative than individuals.

Teams are interactive settings where people learn from one another and share job skills and knowledge. The learning environment and the pool of experience within a team can be used to solve difficult and unique problems. This is especially helpful to newcomers, who often need help in their jobs. When team members support and help each other in acquiring and improving job competencies, they may even make up for deficiencies in organizational training systems.

Teams are also important sources of need satisfaction for their members. Opportunities for social interaction within a team can provide individuals with a sense of security through work assistance and technical advice. Team members can also provide emotional support for one another in times of special crisis or pressure. The many contributions individuals make to teams can help members experience self-esteem and personal involvement.

Social Facilitation

Social Facilitation

Teams are also settings for something known as social facilitation—the tendency for one's behavior to be influenced by the presence of others in a group or social setting.19 In a team context it can be a boost or a detriment to an individual member's performance contributions.

Social facilitation is the tendency for one's behavior to be influenced by the presence of others in a group.

Social facilitation theory suggests that working in the presence of others creates an emotional arousal or excitement that stimulates behavior and affects performance. The effect is positive and stimulates extra effort when one is proficient with the task at hand. An example is the team member who enthusiastically responds when asked to do something she is really good at, such as making slides for a team presentation. But the effect of social facilitation can be negative when the task is unfamiliar or a person lacks the necessary skills. A team member might withdraw, for example, when asked to do something he or she isn't very good at.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

Social Loafing and Team Problems

Social Loafing and Team Problems

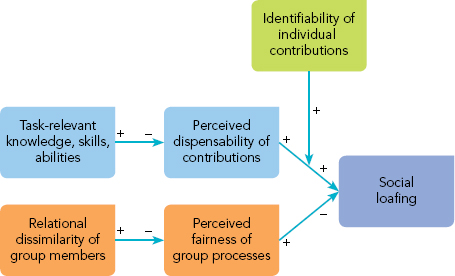

Although teams have enormous performance potential, one of their problems is social loafing. Also known as the Ringlemann effect, it is the tendency of people to work less hard in a group than they would individually.20 Max Ringlemann, a German psychologist, pinpointed the phenomenon by asking people to pull on a rope as hard as they could, first alone and then as part of a team.21 Average productivity dropped as more people joined the rope-pulling task. Ringlemann suggested that people may not work as hard in groups because their individual contributions are less noticeable in the group context and because they prefer to see others carry the workload.

Social loafing occurs when people work less hard in groups than they would individually.

You may have encountered social loafing in your work and study teams, and been perplexed in terms of how to best handle it. Perhaps you have even been surprised at your own social loafing in some performance situations. Rather than give in to the phenomenon and its potential performance losses, you can often reverse or prevent social loafing. Steps that team leaders can take include keeping group size small and redefining roles so that free-riders are more visible and peer pressures to perform are more likely, increasing accountability by making individual performance expectations clear and specific, and making rewards directly contingent on an individual's performance contributions.22

Other common problems and difficulties can easily turn the great potential of teams into frustration and failure. Personality conflicts and differences in work styles can disrupt relationships and create antagonisms. Task uncertainties and competing goals or visions may cause some team members to withdraw and reduce their participation. Ambiguous agendas or ill-defined problems can also cause fatigue and loss of motivation when teams work too long on the wrong things with little to show for it. Finally, not everyone is always ready to do group work. This might be due to lack of motivation, but it may also stem from conflicts with other work deadlines and priorities. Low enthusiasm may also result from perceptions of poor team organization or progress, as well as from meetings that seem to lack purpose.

Stages of Team Development

![]() FORMING STAGE

FORMING STAGE ![]() STORMING STAGE

STORMING STAGE ![]() NORMING STAGE

NORMING STAGE

PERFORMING STAGE ![]() ADJOURNING STAGE

ADJOURNING STAGE

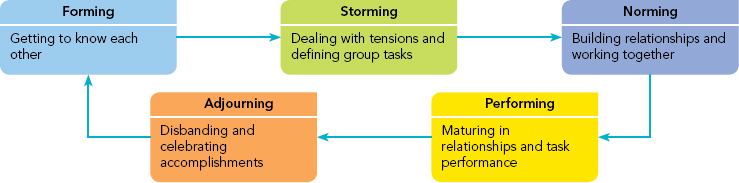

There is no doubt that the pathways to team effectiveness are often complicated and challenging. One of the first things to consider—whether we are talking about a formal work unit, a task force, a virtual team, or a self-managing team—is the fact that the team passes through a series of life cycle stages.23 Depending on the stage the team has reached, the leader and members can face very different challenges and the team may be more or less effective. Figure 7.2 describes the five stages of team development as forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning.24

Forming Stage

Forming Stage

In the forming stage of team development, a primary concern is the initial entry of members to a group. During this stage, individuals ask a number of questions as they begin to identify with other group members and with the team itself. Their concerns may include “What can the group offer me?” “What will I be asked to contribute?” “Can my needs be met at the same time that I contribute to the group?” Members are interested in getting to know each other and discovering what is considered acceptable behavior, in determining the real task of the team, and in defining group rules.

The forming stage focuses around the initial entry of members to a team.

Storming Stage

Storming Stage

The storming stage of team development is a period of high emotionality and tension among the group members. During this stage, hostility and infighting may occur, and the team typically experiences many changes. Coalitions or cliques may form as individuals compete to impose their preferences on the group and to achieve a desired status position. Outside demands such as premature performance expectations may create uncomfortable pressures. In the process, membership expectations tend to be clarified, and attention shifts toward obstacles standing in the way of team goals. Individuals begin to understand one another's interpersonal styles, and efforts are made to find ways to accomplish team goals while also satisfying individual needs.

The storming stage is one of high emotionality and tension among team members.

Norming Stage

Norming Stage

The norming stage of team development, sometimes called initial integration, is the point at which the members really start to come together as a coordinated unit. The turmoil of the storming stage gives way to a precarious balancing of forces. While enjoying a new sense of harmony, team members will strive to maintain positive balance, but holding the team together may become more important to some than successfully working on the team tasks. Minority viewpoints, deviations from team directions, and criticisms may be discouraged as members experience a preliminary sense of closeness. Some members may mistakenly perceive this stage as one of ultimate maturity. In fact, a premature sense of accomplishment at this point needs to be carefully managed in order to reach the next level of team development: performing.

The norming stage is reached when members start to work together as a coordinated team.

FIGURE 7.2 Five stages of team development.

FIGURE 7.3 Ten criteria for measuring the maturity of a team.

Performing Stage

Performing Stage

The performing stage of team development, sometimes called total integration, marks the emergence of a mature, organized, and well-functioning team. Team members are now able to deal with complex tasks and handle internal disagreements in creative ways. The structure is stable, and members are motivated by team goals and are generally satisfied. The primary challenges are continued efforts to improve relationships and performance. Team members should be able to adapt successfully as opportunities and demands change over time. A team that has achieved the level of total integration typically scores high on the criteria of team maturity as shown in Figure 7.3.

The performing stage marks the emergence of a mature and well-functioning team.

Adjourning Stage

Adjourning Stage

A well-integrated team is able to disband, if required, when its work is accomplished. The adjourning stage of team development is especially important for the many temporary teams such as task forces, committees, project teams, and the like. Their members must be able to convene quickly, do their jobs on a tight schedule, and then adjourn—often to reconvene later if needed. Their willingness to disband when the job is done and to work well together in future responsibilities, team or otherwise, is an important long-term test of team success.

In the adjourning stage, teams disband when their work is finished.

Input Foundations for Teamwork

![]() TEAM RESOURCES AND SETTING

TEAM RESOURCES AND SETTING ![]() NATURE OF THE TEAM TASK

NATURE OF THE TEAM TASK

TEAM SIZE ![]() TEAM COMPOSITION

TEAM COMPOSITION

MEMBERSHIP DIVERSITY AND TEAM PERFORMANCE

It's common for managers and consultants to speak about the importance of having “the right players in the right seats on the same bus, headed in the same direction.”25 This wisdom is quite consistent with the findings of OB scholars. One of the ways to put it into practice is to understand the open systems model presented in Figure 7.4. It shows team effectiveness being influenced by both team inputs—“right players in the right seats”—and team processes—“on the same bus, headed in the same direction.”26 You can remember the point with this equation:

FIGURE 7.4 An open systems model of team effectiveness.

Team effectiveness = Quality of inputs × (Process gains — Process losses)

As shown in the above equation, team inputs establish the initial foundations for team performance. They set the stage for how processes like communication, conflict, and decision making play out in action. And the fact is that the stronger the input foundations of a team, the more likely it is that processes will be smooth and performance will be effective. Key team inputs include resources and setting, the nature of the task, team size, and team composition.

Team Resources and Setting

Team Resources and Setting

Appropriate goals, well-designed reward systems, adequate resources, and appropriate technology are all essential to support the work of teams. Performance can suffer when team goals are unclear, insufficiently challenging, or arbitrarily imposed. It can also suffer if goals and rewards are focused too much on individual-level instead of group-level accomplishments. In addition, it can suffer when resources—information, budgets, work space, deadlines, rules and procedures, technologies, and the like—are insufficient to accomplish the task. By contrast, getting the right resources in place sets a strong launching pad for team success.

The importance of physical setting to teamwork is evident in the attention now being given to office architecture. Simply said, putting a team in the right workspace can go a long way toward nurturing teamwork. At SEI Investments, for example, employees work in a large, open space without cubicles or dividers. Each person has a private set of office furniture and fixtures, but everything is on wheels. Technology easily plugs and unplugs from suspended power beams that run overhead. This makes it easy for project teams to convene and disband as needed and for people to meet and converse intensely within the ebb and flow of daily work.27

Team Task

Team Task

The nature of the task is always an important team input because different tasks place different demands on teamwork. When tasks are clear and well defined, it's quite easy for members to both know what they are trying to accomplish and work together while doing it. But, team effectiveness is harder to achieve with complex tasks.28 Such tasks require lots of information exchange and intense interaction, and everything takes place under conditions of some uncertainty. To deal well with complexity and achieve desired results, team members have to fully mobilize their talents and use the available resources well. When teams succeed with complex tasks, however, members tend to experience high satisfaction.

One way to analyze the nature of the team task is in terms of its technical and social demands. The technical demands of a task include the degree to which it is routine or not, the level of difficulty involved, and the information requirements. The social demands of a task involve the degree to which issues of interpersonal relationships, egos, controversies over ends and means, and the like come into play. Tasks that are complex in technical demands require unique solutions and more information processing. Those that are complex in social demands pose difficulties for reaching agreement on goals and methods to accomplish them.

Team Size

Team Size

The size of a team can have an impact on team effectiveness. As a team becomes larger, more people are available to divide up the work and accomplish needed tasks. This can boost performance and member satisfaction, but only up to a point. Communication and coordination problems arise at some point because of the sheer number of linkages that must be maintained. Satisfaction may dip, and turnover, absenteeism, and social loafing may increase. Even logistical matters, such as finding time and locations for meetings, become more difficult for larger teams.29

The ideal size of creative and problem-solving teams is probably between five and seven members, or just slightly larger. Those with fewer than five may be too small to adequately share all the team responsibilities. With more than seven, individuals may find it harder to join in the discussions, contribute their talents, and offer ideas. Larger teams are also more prone to possible domination by aggressive members and have tendencies to split into coalitions or subgroups.30 Amazon.com's founder and CEO, Jeff Bezos, is a great fan of teams. But he also has a simple rule when it comes to the size of Amazon's product development teams: No team should be larger than two pizzas can feed.31

When voting is required, odd-numbered teams are preferred to help rule out tie votes. When careful deliberations are required and the emphasis is more on consensus, such as in jury duty or very complex problem solving, even-numbered teams may be more effective. The even number forces members to confront disagreements and deadlocks rather than simply resolve them by majority voting.32

Team Composition

Team Composition

“If you want a team to perform well, you've got to put the right members on the team to begin with.” It's advice we hear a lot. There is no doubt that one of the most important input factors is the team composition. You can think of this as the mix of abilities, personalities, backgrounds, and experiences that the members bring to the team. The basic rule of thumb for team composition is to choose members whose talents and interests fit well with the tasks to be accomplished, and whose personal characteristics increase the likelihood of being able to work well with others.

Team composition is the mix of abilities, skills, personalities, and experiences that the members bring to the team.

Ability counts in team composition, and it's a top priority when selecting members. The team is more likely to perform better when its members have skills and competencies that best fit task demands. Although talents alone cannot guarantee desired results, they do establish an important baseline of high performance potential. Let's not forget, however, that it takes more than raw talent to generate team success. Surely you've been on teams or observed teams where there was lots of talent but very little teamwork. A likely cause is that the blend of members caused relationship problems over everything from needs to personality to experience to age and other background characteristics.

Needs count too. The FIRO-B theory (FIRO = fundamental interpersonal relations orientation) identifies differences in how people relate to one another in groups based on their needs to express and receive feelings of inclusion, control, and affection.33 Developed by William Schultz, the theory suggests that teams whose members have compatible needs are likely to be more effective than teams whose members are more incompatible. Symptoms of incompatibilities include withdrawn members, open hostilities, struggles over control, and domination by a few members. Schultz states the management implications of the FIRO-B theory this way: “If at the outset we can choose a group of people who can work together harmoniously, we shall go far toward avoiding situations where a group's efforts are wasted in interpersonal conflicts.”34

FIRO-B theory examines differences in how people relate to one another based on their needs to express and receive feelings of inclusion, control, and affection.

Another issue in team composition is status in terms relative rank, prestige, or social standing. Status congruence occurs when a person's position within the team is equivalent in status to positions the individual holds outside of it. Any status incongruence may create problems. Consider something that is increasingly common today—generationally blended teams. Things may not go smoothly, for example, when a young college graduate is asked to head a project team on social media and whose members largely include senior and more experienced workers.

Status congruence involves consistency between a person's status within and outside a group.

Membership Diversity and Team Performance

Membership Diversity and Team Performance

Diversity is always an important aspect of team composition. The presence of different values, personalities, experiences, demographics, and cultures among members can bring both opportunities and problems.35

Teamwork usually isn't much of a problem in homogeneous teams where members are very similar to one another. The members typically find it quite easy to work together and enjoy the team experience. Yet, researchers warn about the risks of homogeneity. Although it may seem logical that having members similar to one another is an asset, it doesn't necessarily work out that way. Research points out that teams composed of members who are highly similar in background, training, and experience often underperform even though the members may enjoy a sense of harmony and feel very comfortable with one another.36

In homogeneous teams members share many similar characteristics.

Teamwork problems are likely in heterogeneous teams where members are very dissimilar to one another. The mix of diverse personalities, experiences, backgrounds, ages, and other personal characteristics may create difficulties as members try to define problems, share information, mobilize talents, and deal with obstacles or opportunities. Nevertheless, if—and this is a big “if”—members can work well together, the diversity can be a source of advantage and enhanced performance potential.37

In heterogeneous teams members differ in many characteristics.

Team process and performance difficulties due to diversity issues are especially likely to occur in the initial stages of team development. The so-called diversity–consensus dilemma is the tendency for diversity to make it harder for team members to work together, especially in the early stages of their team lives, even though the diversity itself expands the skills and perspectives available for problem solving.38 These dilemmas may be most pronounced in the critical zone of the storming and norming stages of development as described in Figure 7.5. Problems may occur as interpersonal stresses and conflicts emerge from the heterogeneity. The challenge to team effectiveness is to take advantage of diversity without suffering process disadvantages.39

Diversity–consensus dilemma is the tendency for diversity in groups to create process difficulties even as it offers improved potential for problem solving.

Working through the diversity–consensus dilemma can slow team development and impede relationship building, information sharing, and problem solving.40 Some teams get stuck here and can't overcome their process problems. If and when such difficulties are resolved, diverse teams can emerge from the critical zone with effectiveness and often outperform less diverse ones. Research also shows that the most creative teams include a mix of old-timers and newcomers.41 The old-timers have the experience and connections; the newcomers bring in new talents and fresh thinking.

The diversity and performance relationship is evident in research on collective intelligence—the ability of a group or team to perform well across a range of tasks.42 Researchers have found only a slight correlation between average or maximum individual member intelligence and the collective intelligence of teams. But, they find strong correlations between collective intelligence and two process variables—social sensitivities within the teams and absence of conversational domination by a few members. Furthermore, collective intelligence is associated with gender diversity, specifically the proportion of females on the team. This finding also links to process, with researchers pointing out that females in their studies scored higher than males on social sensitivity.

Collective intelligence is the ability of a team to perform well across a range of tasks.

FIGURE 7.5 Member diversity, stages of team development, and team performance.

7 Study Guide

Key Questions and Answers

What are teams, and how are they used in organizations?

- A team is a group of people working together to achieve a common purpose for which they hold themselves collectively accountable.

- Teams help organizations by improving task performance; teams help members experience satisfaction from their work.

- Teams in organizations serve different purposes—some teams run things, some teams recommend things, and some teams make or do things.

- Organizations consist of formal teams that are designated by the organization to serve an official purpose, as well as informal groups that emerge from special relationships but are not part of the formal structure.

- Organizations can be viewed as interlocking networks of permanent teams such as project teams and cross-functional teams, as well as temporary teams such as committees and task forces.

- Members of self-managing teams typically plan, complete, and evaluate their own work, train and evaluate one another in job tasks, and share tasks and responsibilities.

- Virtual teams, whose members meet and work together through computer mediation, are increasingly common and pose special management challenges.

When is a team effective?

- An effective team achieves high levels of task accomplishment, member satisfaction, and viability to perform successfully over the long term.

- Teams help organizations through synergy in task performance, the creation of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

- Teams help satisfy important needs for their members by providing them with things like job support and social interactions.

- Team performance can suffer from social loafing when a member slacks off and lets others do the work.

- Social facilitation occurs when the behavior of individuals is influenced positively or negatively by the presence of others on a team.

What are the stages of team development?

- In the forming stage, team members come together and form initial impressions; it is a time of task orientation and interpersonal testing.

- In the storming stage, team members struggle to deal with expectations and status; it is a time when conflicts over tasks and how the team works are likely.

- In the norming or initial integration stage, team members start to come together around rules of behavior and what needs to be accomplished; it is a time of growing cooperation.

- In the performing or total integration stage, team members are well organized and well functioning; it is a time of team maturity when performance of even complex tasks becomes possible.

- In the adjourning stage, team members achieve closure on task performance and their personal relationships; it is a time of managing task completion and the process of disbanding.

How can we understand teams at work?

- Teams are open systems that interact with their environments to obtain resources that are transformed into outputs.

- The equation summarizing the open systems model for team performance is this: Team effectiveness = Quality of inputs × (Process gains − Process losses)

- Input factors such as resources and setting, nature of the task, team size, and team composition, establish the core performance foundations of a team.

- Team processes include basic group or team dynamics that show up as the ways members work together to use inputs and complete tasks.

Terms to Know

Adjourning stage (p. 152)

Collective intelligence (p. 157)

Cross-functional team (p. 144)

Diversity–consensus dilemma (p. 157)

Effective team (p. 148)

Employee involvement team (p. 144)

FIRO-B theory (p. 156)

Formal teams (p. 143)

Forming stage (p. 151)

Functional silos problem (p. 144)

Heterogeneous teams (p. 157)

Homogeneous teams (p. 156)

Informal groups (p. 143)

Multiskilling (p. 145)

Norming stage (p. 151)

Performing stage (p. 152)

Problem-solving team (p. 144)

Quality circle (p. 145)

Self-managing team (p. 145)

Social facilitation (p. 148)

Social loafing (p. 149)

Social network analysis (p. 143)

Status congruence (p. 156)

Storming stage (p. 151)

Synergy (p. 148)

Team (p. 142)

Team composition (p. 156)

Teamwork (p. 142)

Virtual team (p. 146)

Self-Test 1

Multiple Choice

Multiple Choice

- The FIRO-B theory deals with ________ in teams.

- (a) membership compatibilities

- (b) social loafing

- (c) dominating members

- (d) conformity

- It is during the _________ stage of team development that members begin to come together as a coordinated unit.

- (a) storming

- (b) norming

- (c) performing

- (d) total integration

- An effective team is defined as one that achieves high levels of task performance, member satisfaction, and ________.

- (a) coordination

- (b) harmony

- (c) creativity

- (d) team viability

- Task characteristics, reward systems, and team size are all ________ that can make a difference in team effectiveness.

- (a) processes

- (b) dynamics

- (c) inputs

- (d) rewards

- The best size for a problem-solving team is usually __________ members.

- (a) no more than 3 or 4

- (b) 5 to 7

- (c) 8 to 10

- (d) around 12 to 13

- When a new team member is anxious about questions such as “Will I be able to influence what takes place?” the underlying issue is one of _________.

- (a) relationships

- (b) goals

- (c) processes

- (d) control

- Self-managing teams _______.

- (a) reduce the number of different job tasks members need to master

- (b) largely eliminate the need for a traditional supervisor

- (c) rely heavily on outside training to maintain job skills

- (d) add another management layer to overhead costs

- Which statement about self-managing teams is most accurate?

- (a) They always improve performance but not satisfaction.

- (b) They should have limited decision-making authority.

- (c) They operate with elected team leaders.

- (d) They should let members plan and control their own work.

- When a team of people is able to achieve more than what its members could by working individually, this is called ________.

- (a) distributed leadership

- (b) consensus

- (c) team viability

- (d) synergy

- Members of a team tend to become more motivated and better able to deal with conflict during the __________ stage of team development.

- (a) forming

- (b) norming

- (c) performing

- (d) adjourning

- The Ringlemann effect describes _________.

- (a) the tendency of groups to make risky decisions

- (b) social loafing

- (c) social facilitation

- (d) the satisfaction of members' social needs

- Members of a multinational task force in a large international business should probably be aware that ________ might initially slow the progress of the team.

- (a) synergy

- (b) groupthink

- (c) the diversity–consensus dilemma

- (d) intergroup dynamics

- When a team member engages in social loafing, one of the recommended strategies for dealing with this situation is to _________.

- (a) forget about it

- (b) ask another member to force this person to work harder

- (c) give the person extra rewards and hope he or she will feel guilty

- (d) better define member roles to improve individual accountability

- When a person holds a prestigious position as a vice president in a top management team, but is considered just another member of an employee involvement team that a lower-level supervisor heads, the person might experience _________.

- (a) role underload

- (b) role overload

- (c) status incongruence

- (d) the diversity–consensus dilemma

- The team effectiveness equation states: Team effectiveness = ___________ × (Process gains — Process losses).

- (a) Nature of setting

- (b) Nature of task

- (c) Quality of inputs

- (d) Available rewards

Short Response

Short Response

16. In what ways are teams good for organizations?

17. What types of formal teams are found in organizations today?

18. What are members of self-managing teams typically expected to do?

19. What is the diversity–consensus dilemma?

Applications Essay

Applications Essay

20. One of your Facebook friends has posted this note: “Help! I have just been assigned to head a new product design team at my company. The division manager has high expectations for the team and me, but I have been a technical design engineer for four years since graduating from college. I have never ‘managed’ anyone, let alone led a team. The manager keeps talking about her confidence that I will be very good at creating lots of teamwork. Does anyone out there have any tips to help me master this challenge?” You smile while reading the message and start immediately to formulate your recommendations. Exactly what message will you send?

Steps to Further Learning 7

Top Choices from The OB Skills Workbook

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook found at the back of the book are suggested for Chapter 7.

“You should take off the headphones in the office, that's not the way we do things here.”

“You should take off the headphones in the office, that's not the way we do things here.”