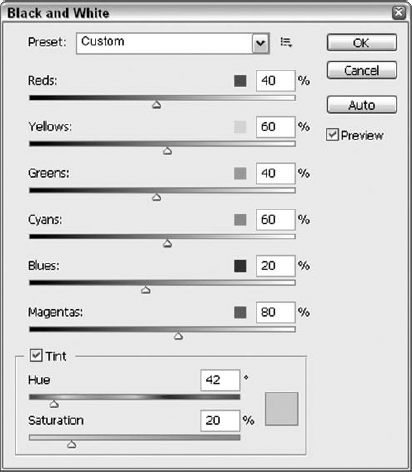

Color mapping is a term that doesn't really explain itself. Both of the words make sense, but paired up, what to do they mean? Maybe color converting might be a better term, or perhaps color organization or assignment. Anyway, we're stuck with color mapping, at least in a technical sense, and the term simply refers to the process of shuffling colors around, taking them from where they are now to where you want or need them to be. For example, to map Color A to Color B simply means to take all the A-colored pixels and convert them to B-colored pixels. Photoshop provides several commands that enable you to map entire ranges of colors based on their hues, saturation levels, and most frequently, brightness values. They've even added a new one — Black and White — that we'll delve into later in the chapter.

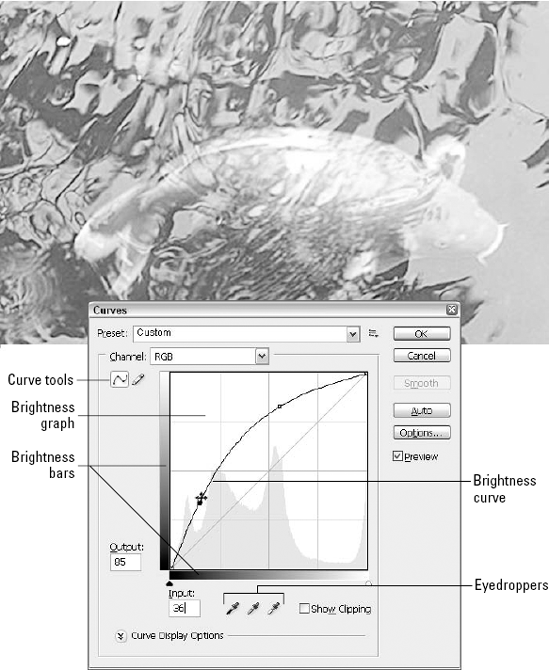

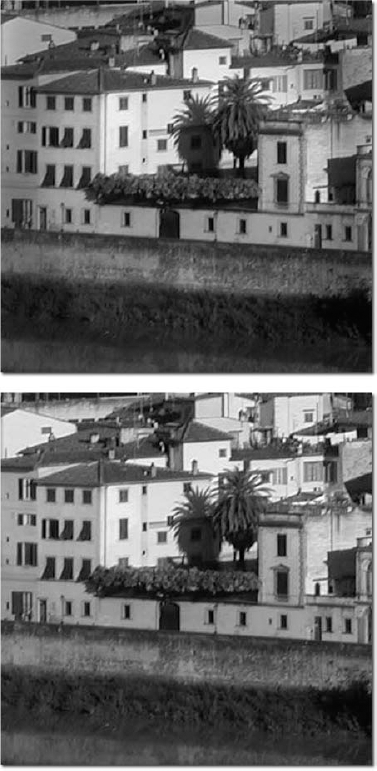

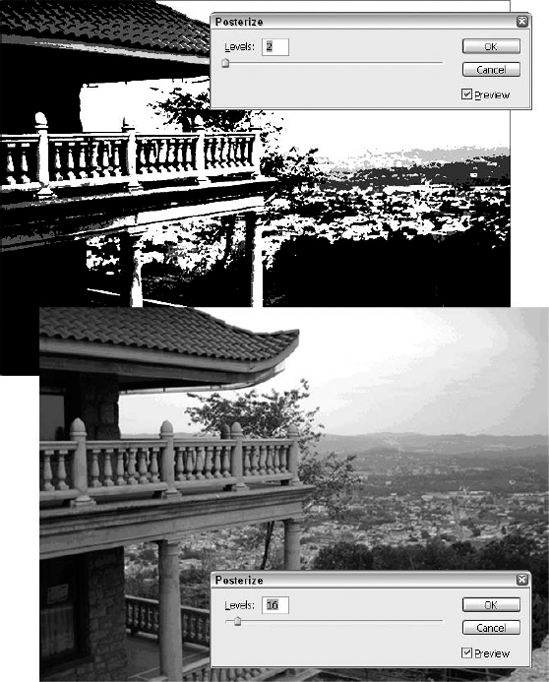

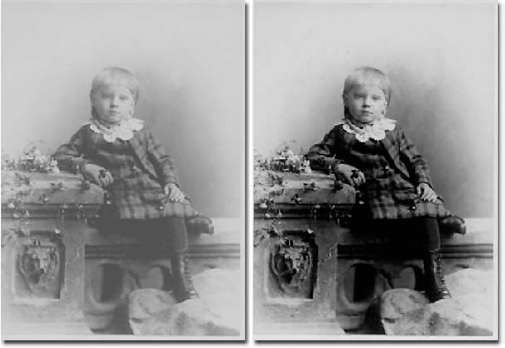

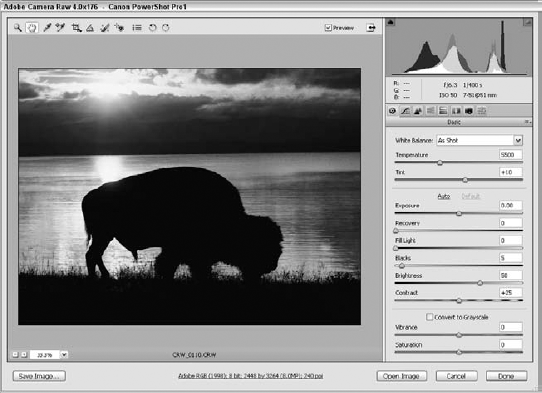

You may want to change colors in your photos and other artwork for lots of reasons. Perhaps you want to achieve some special effect or improve the clarity of an image or make some portion of the image stand out more so than it does under its current color scheme. In Figure 18.1, the image at the bottom is greatly improved by color mapping that was applied to the original version of the same image at the top: The colors stand out, edges are crisper and cleaner, and detail is much more evident. Of course, this is a black and white book (except for the Color Section), so the only things you can see here are the "crisper and cleaner" and the increase in detail. But believe it, the colors are the culprits, both in the original and the re-mapped version. The image in the middle shows the sort of "special" effects you also can achieve when tinkering with color settings.

While some mapping is done to create special — sometimes psychedelic — effects, most of the time the sort of correction or improvement shown in the bottom image in Figure 18.1 is the goal. You're making straightforward repairs, alternatively known as color adjustments and corrections. The reasons to need or want to make such adjustments or corrections are plentiful. Scans are never perfect, no matter how much money you spend on a scanning device or a service bureau. They can always benefit from tweaking and subtle adjustments, if not outright overhauls, in the color department. And, of course, digital cameras, and certainly lower-end traditional film cameras and their development methods can create images with colors that leave much to be desired.

Of course, Photoshop's color adjustment functions can't make something from nothing. In creating the illusion of more and better colors, most of the color adjustment operations that you perform actually take some small amount of color away from the image. Somewhere in your image, two pixels that were two different colors before you started the correction change to the same color. The image may look ten times better, but it will in fact be less colorful than when you started.

Remembering this principle is important because it demonstrates that color mapping is really a balancing act. The first several operations you perform may make an image look progressively better, but the tenth may send it into decline — the perfect example of less being more, or knowing when to quit. This knowledge, however, of when to quit or when correction has become corruption is a matter of experience and developing a good "eye" for when that line has been crossed. Of course there's no magic formula; the amount of color mapping you need to apply varies from image to image. But if you follow basic principles — use the commands in moderation, know when to stop, and save your image to disk before doing anything drastic — you should be happy with your results the majority of the time.

Note

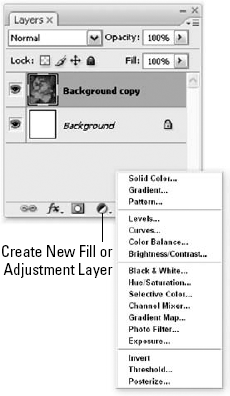

Many of the commands discussed in the following sections also can be applied as adjustment layers. An adjustment layer is an extremely flexible tool, giving you all the advantages of the color correction commands without the drawback of having your original image permanently altered. Adjustment layers are discussed in full at the end of this chapter, but you should know they're "out there" from the beginning of any discussion of color mapping and image correction; this knowledge can help you put all the techniques covered between now and then in better perspective, evaluating the differences between techniques, weighing pros and cons, and so on. So there, now you know.

Figure 18.1. From bad to bizarre to better, color adjustments can serve many different purposes. The top image (original) is faded and blurry, and a gradient map makes it interesting — but not clearer or crisper, as it appears in the bottom image after some corrections were made to light and color levels.

Photoshop stores all its color mapping commands under the Image

Color mapping: Commands such as Invert and Threshold are quick-and-dirty color mappers, swapping, for example, the original colors for their color opposites (Invert). They don't correct images, but they can be useful for creating special effects and adjusting masks.

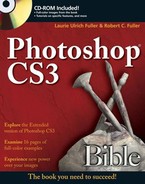

Easy color corrections: Brightness/Contrast and Color Balance are true color-correction commands, but you may feel that they sacrifice functionality for ease of use. By ease of use, we mean that the corrections are achieved through a few simple sliders, as shown in Figure 18.2. By sacrifice functionality, we also mean that the corrections are achieved through a few simple sliders. Too few. But you will end up using them from time to time, even if you think they're painfully simple and wish they offered more or more nuanced controls.

One thing that is improved in Brightness/Contrast in Photoshop CS3 is the addition of the Use Legacy checkbox. By turning this on, you can elect to clip extreme highlight and shadow detail. It's off by default, but when you turn it on, changes to brightness and contrast are made on a non-linear basis — mid-tones are effected to a greater extent than highlights or shadows — unlike the CS2 and previous versions of this tool, which affected highlights, midtones, and shadows to the same degree as you dragged the slider/s.

Expert color corrections: The third, more complicated variety of color-correction commands provides better control, but they take a fair amount of effort to learn. Levels, Curves, Hue/Saturation, and Shadows/Highlights are examples of color correcting at both its best and most complicated.

This chapter contains little information about the second category of commands for the simple reason that so little information is required. You issue a command from the Image

Now, it's important to state up front that some of the quick and automatic adjustment tools aren't going to wow you, even when you consider their incredible speed and ease of use. Some exceptions: Auto Color, which usually does a pretty good job of adjusting an image's midtones and removing color casts; Auto Levels and Auto Contrast, which are decent quick fixers; and Variations, which offers deceptively straightforward sophistication; this last one's not really that automatic compared with the others, in that you have several choices of color and lighting adjustments that you can make and you can confine the adjustments to specific ranges of color.

No matter how you end up feeling about the individual commands and the three types of adjustments that can be made, you're about to master them — so grab a really dysfunctional photo and let the color therapy begin.

The first category of commands, the color mapping tools, all occupy one of the lower sections in the Image

When you choose Image

Note

Now, you might have already thought, "Hey, this means I can scan a negative and convert it to a positive image with this command!" Well, not really, at least not that simply. By itself, the Invert command is not sufficient to convert a scanned color photographic negative to a positive. Negative film produces an orange cast that the Invert command does not address. After inverting, you can use the Variations command to remove the colorcast. Or avoid Invert altogether, and use the Levels command to invert the image. Both Variations and Levels are explained later in this chapter.

One really good thing about the Invert command is that it's just about the only color-mapping command that retains the rich diversity of color in an image. (The Hue/Saturation command also retains color diversity under specific conditions.) For example, if you apply the Invert command twice in a row, you arrive at your original image without any loss in quality. Cool, no?

Figure 18.3. You can turn some or all of your image to its negative. Here the top half of the image has been inverted, showing you the before and after in one image.

Of course, bear in mind that when you're working on a full-color image, the Invert command simply inverts the contents of each color channel. This means the command produces very different results when applied to RGB, Lab, and especially CMYK images. Typically, the Invert command changes most pixels in a CMYK image to black. Except in rare instances — such as in night scenes — the black channel contains lots of light shades and few dark shades. So when you invert the channel, it becomes extremely dark.

Note

Just so you know, when we discuss applying color corrections in the CMYK mode, we assume that you're applying them after choosing Image

Tip

As mentioned in Chapter 13, inverting the contents of the mask channel is the same as applying Select

When you invoke the Equalize command, Photoshop searches for the lightest and darkest color values in a selection and then maps the lightest color in all the color channels to white, maps the darkest color in the channels to black, and distributes the remaining colors to other brightness levels in an effort to evenly distribute pixels over the entire brightness spectrum. This doesn't mean that any one pixel actually appears white or black after you apply Equalize, however. Instead, one pixel in at least one channel is white and another pixel in at least one channel is black. In an RGB image, for example, the red, green, or blue component of one pixel would be white, but the other two components of that same pixel might be black. The result is a higher contrast image with white and black pixels scattered throughout the color channels.

If no portion of the image is selected when you choose Image

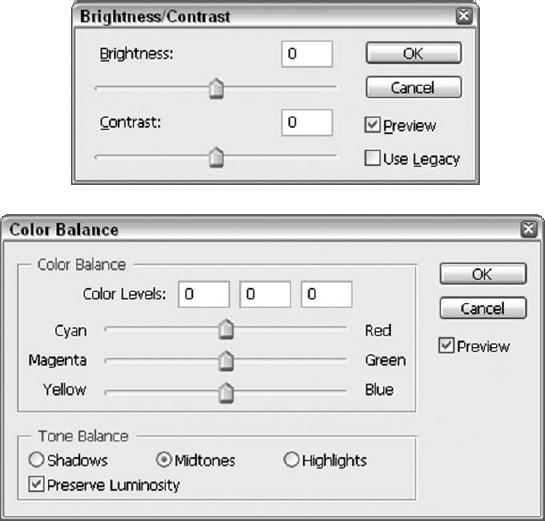

Equalize Selected Area Only: Select this option to apply the Equalize command strictly within the confines of the selection. The lightest pixel in the selection becomes white, the darkest pixel becomes black, and the others remap to shades in between. Figure 18.4, at the top, shows an image that's been Equalized in only one selected area.

Equalize Entire Image Based on Selected Area: If you select the second radio button, which is the default setting, Photoshop applies the Equalize command to the entire image based on the lightest and darkest colors in the selection. All colors in the image that are lighter than the lightest color in the selection become white, and all colors darker than the darkest color in the selection become black. The bottom image in Figure 18.4 shows the same image with the Equalize command applied to the entire image based on the same selection.

What you may find with the Equalize command is that it can rely too heavily on the automation of its procedure to be of much use as a color-correction tool. You simply don't have enough control over the equalization process, or the equation it's using to distribute colors over the entire spectrum of light to dark. You can create some interesting special effects, though, and sometimes it can be a helpful command, depending on the photo in question, its problems, and your goals for it.

Tip

If you really want to automatically adjust the colors in an image from black to white regardless of the color mode and composition of the individual channels, choose Image

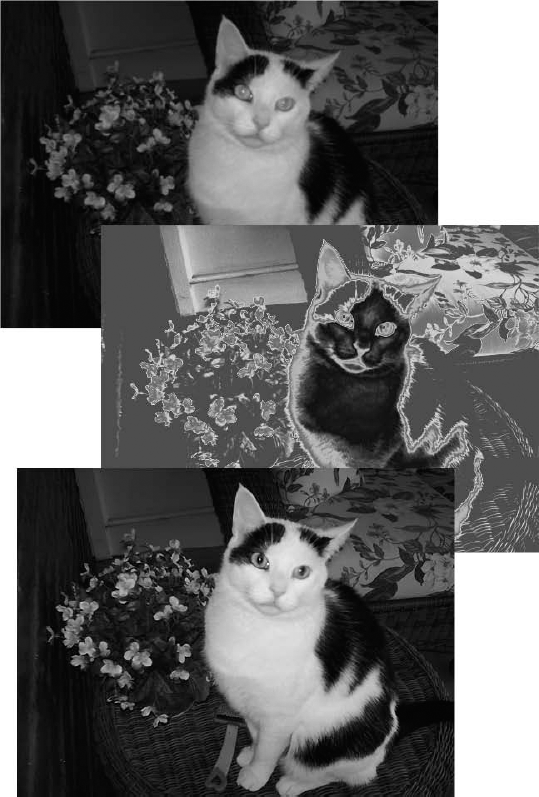

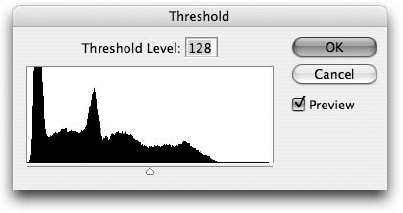

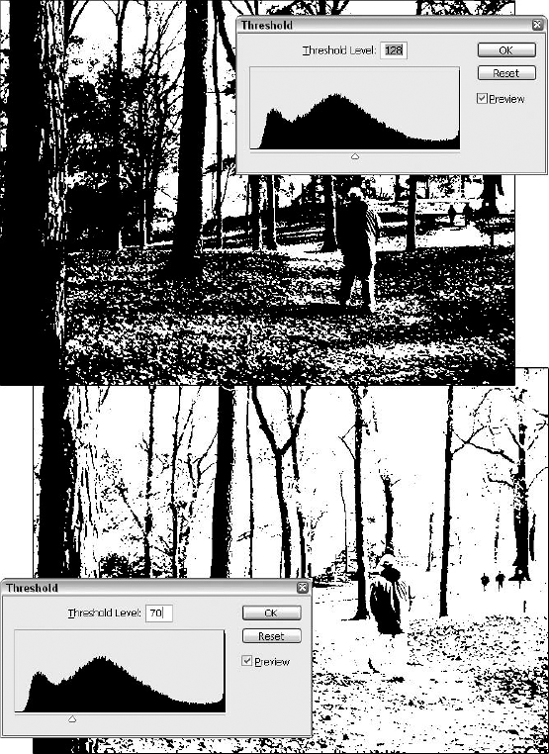

The Threshold command converts all colors to either black or white, based on their brightness values. When you choose Image

Figure 18.5. The histogram in the Threshold dialog box shows the distribution of brightness values in the selection. The weird mountain-range silhouette thing is what's known as a histogram.

The dialog box also includes a graph of all the colors in the image, even if only a portion of the image is selected. This graph is called a histogram. The width of the histogram represents all 256 possible brightness values, starting at black on the left and progressing to white on the right. The height of each vertical line in the graph demonstrates the number of pixels currently associated with that brightness value. Therefore, you can use the histogram to gauge the distribution of lights and darks in your image. You may have trouble imagining that looking at the histogram in a dialog box could ever translate to a useful tool for perceiving and adjusting color, but with enough experience, the histogram becomes an invaluable tool, permitting you to greatly improve the colors that you see onscreen. You may even get excited enough about histograms to spend some time using the Histogram palette, discussed later in this chapter.

Generally speaking, you achieve the best effects if you change an equal number of pixels to black as you change to white (and vice versa). So rather than moving the slider bar to 128, which is the medium brightness value, move it to the point at which the area of the vertical lines to the left of the slider triangle looks roughly equivalent to the area of the vertical lines to the right of the slider triangle. The example at the top in Figure 18.6 shows the result of applying the Threshold command with a Threshold Level value of 128 (right smack in the middle of the slider), while the image at the bottom shows a lower Threshold level of 70.

Tip

If you want to achieve a colorful Threshold effect, try applying the Threshold command independently to each color channel. In an RGB image, for example, press Ctrl+1 (

Where Threshold boils down an image into only two colors, Posterize can retain as many colors as you like. Of course, you can't control how colors are mapped, as you can when you use Threshold; the Posterize dialog box provides neither a histogram nor a slider bar. Instead, Posterize automatically divides the full range of 256 brightness values into a specified number of equal increments.

To use this command, choose Image

Like Threshold, the Posterize command is something you can play with in conjunction with filters to get some really interesting results. You can apply it before a filter or after it — or along with more than one filter. By reducing the number of levels and thus simplifying the color palette in the image, the Posterize command makes various filters perform differently than they would on a photo with millions of colors.

Figure 18.6. Use the histogram and your own eyes — trained on the preview — to determine when the Threshold command is delivering interesting or simply destructive results.

Figure 18.7. On the top, Posterize was applied at two levels. On the bottom, 16 levels were applied, which makes the image look almost "normal," like the original photo with millions of colors. Note that the sky is one of the giveaway areas: Bands of colors are visible there more than in the busier areas of the image.

Photoshop offers four quick, automatic correctors under the Image

The Desaturate command is quite useful for removing color from selected areas or from independent layers. You can use it to reduce or remove color from an entire image, but for that you'd probably be better off using the Image

You want to retain the option of applying RGB-only filters, such as Lens Flare and Lighting Effects. You'd lose these options if you convert to Grayscale.

You intend to downsize the colors using Image

Tip

You can use Edit

Note

Desaturate isn't the only way to remove colors from an image. You also can invert the colors and mix them with their original counterparts to achieve a slightly different effect. Just press Ctrl+I (

Image

Figure 18.8. After the use of the Auto Levels command, you see more contrast, more discernable detail, more interest.

You may be thinking that Auto Levels is a whole lot like Equalize, and you'd be right — except that unlike the Equalize command, which considers all color channels as a whole, Auto Levels looks at each channel independently. This results in more dynamic, profound results, based on the color mode for the photo. Like Invert, Equalize, and other automatic color mapping commands, Auto Levels is designed for use in the RGB mode. If you use it in CMYK, you may not like the results.

If you find that Image

Not sure which one to use? If a low-contrast image suffers from a colorcast that you want to correct, try Auto Levels. If the image is washed out but the colors are okay, try Auto Contrast. If you're working on a grayscale image, the two commands work the same, so choose whichever is more convenient. Given that neither command is perfect, you may want to make additional Levels and Variations adjustments (these commands are covered in detail later in this chapter) — or try Auto Color, which is up next.

The Auto Color command is such a smart and useful tool that it serves as the exception to the rule that one must be somewhat reserved in praise for or use of any command that starts with the word "Auto." Auto Color is great at tweaking skin tones and making other subtle changes — something you'll notice right away, especially in photos where the Auto Levels and Auto Contrast commands don't seem to make much, if any, difference in the image.

Choose Image

Tip

Auto Color is different from Auto Levels in that rather than setting the darks to black and the lights to white, Auto Color neutralizes an image's highlights, midtones, and shadows, thereby restoring balance to other colors in the image. That's the plan, anyway. If you don't see the results that this command promises, you can always customize it using the Levels and Curves commands — a process discussed later in this chapter.

In this section, you're looking at the commands that change the distribution of colors in an image. You can move the hues across the color spectrum, change the saturation of colors, adjust highlights and shadows, and even tint an image. Four of these commands — Hue/Saturation, Selective Color, Photo Filter, and Match Color — are applicable only to color images. The other two — Replace Color and Variations — can be applied to grayscale images, too. You may find that they're better suited to color images, but it depends on the photo as to whether these commands are the most effective choice for a grayscale image. If you're more interested in editing grayscale photographs, you can check out the Levels, Curves, and new Shadow/Highlight commands, all of which are covered toward the end of the chapter. For those of you who want to correct colors, however, read on.

Tip

Remember how Ctrl+Alt+F (

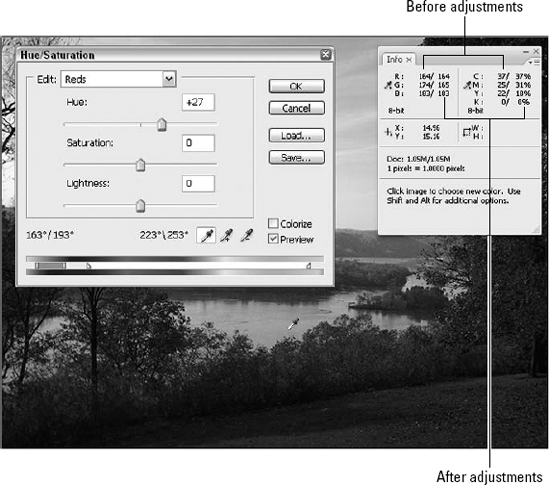

The Hue/Saturation command provides two functions. First, it enables you to adjust colors in an image according to their hues and saturation levels. You can apply the changes to specific ranges of colors or modify all colors equally across the spectrum. And second, the command lets you colorize images by applying new hue and saturation values while retaining the core brightness information from the original image.

This command is perfect for colorizing grayscale images. You can give your images the Ted Turner treatment with just a little effort. Just scan and change the Hue value to 140 degrees.

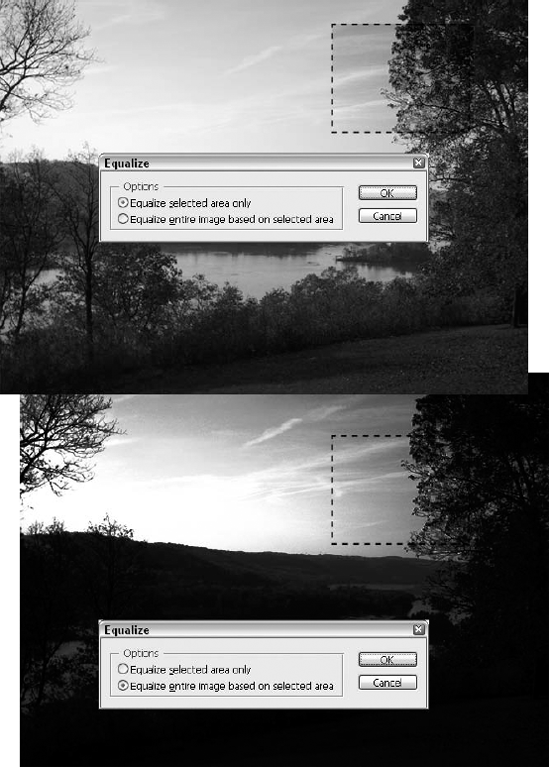

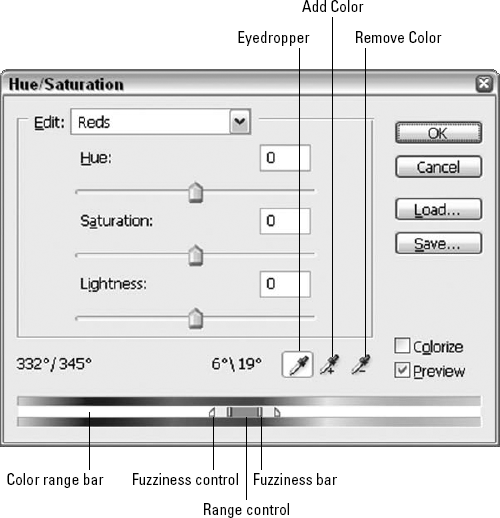

When you choose Image

Hue: The Hue slider bar measures colors on the 360-degree color circle, as explained in the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the HSB model. You can adjust the Hue value from _180 to +180 degrees. As you do, Photoshop rotates the colors around the Hue wheel. Consider the example of flesh tones. A Hue value of +30 moves the flesh into the orange range; a value of +100 makes it green. Going in the other direction, a Hue of −30 makes the flesh red and −100 makes it purple.

Note

When the Colorize option is selected, Hue becomes an absolute value measured from 0 to 360 degrees. A Hue value of 0 is red, 30 is orange, and so on, as described in Chapter 4.

Saturation: The Saturation value changes the intensity of the colors. Normally, the Saturation value varies from −100 for gray to +100 for incredibly vivid hues. The only exception occurs when the Colorize option is selected, in which case saturation becomes an absolute value, measured from 0 for gray to 100 for maximum saturation.

Lightness: You can darken or lighten an image by varying the Lightness value from −100 to +100.

Warning

Because this value invariably changes all brightness levels in an image to an equal extent — whether or not Colorize is selected — it permanently dulls highlights and shadows. We advise that you avoid this option at virtually all costs and rely instead on the Levels or Curves commands to edit brightness and contrast.

Tip

Like many sliders and settings in the program, Photoshop now lets you "scrub" to adjust the values. Position your cursor over the name of one of the sliders (such as Hue) until you get a hand cursor with two arrows protruding from it. Drag left to decrease the value of the slider, drag right to increase it. Shift-drag to change the value in increments of 10.

Edit: The Edit pop-up menu controls which colors in the active selection or layer are affected by the Hue/Saturation command. If you select the Master option, as by default, Hue/Saturation adjusts all colors equally. If you prefer to adjust some colors in the layer differently than others, choose one of the other Edit options or press the keyboard equivalent — Ctrl+1 (Win) or

Each Edit option isolates a predefined range of colors in the image. For example, the Reds option selects the range measured from 345 to 15 degrees on the Hue wheel. Naturally, if you were to modify just the red pixels and left all non-red pixels unchanged, you'd end up with some jagged transitions in your image. So Photoshop softens the edges with 30 degrees of fuzziness at either end of the red spectrum (the same kind of fuzziness as described in Chapter 9).

Tip

You can apply different Hue, Saturation, and Lightness settings for every one of the color ranges. For example, to change all reds in an image to green and all cyans to gray, choose the Reds option and change the Hue value to +50 and then choose Cyans and change the Saturation value to −100.

Color ramps: You can track changes made to colors in the Hue/Saturation dialog box in two ways. One way is to select the Preview option and keep an eye on the changes in the image window. The second way is to observe the color ramps at the bottom of the dialog box. The first ramp shows the 360-degree color spectrum; the second ramp shows what the color ramp looks like after your edits.

Color range controls: You also can use the color ramps to broaden or narrow the range of colors affected by Hue/Saturation. When you choose any option other than Master from the Edit pop-up menu, a collection of color range controls appears between the color ramps. The range bar identifies the selected colors and also permits you to edit them.

Figure 18.11 shows the color range controls up close and personal. Here's how they work:

Drag the central range bar to move the entire color range.

Drag one of the two lighter-colored fuzziness bars to broaden or narrow the color range without affecting the fuzziness.

Drag the range control to change the range while leaving the fuzziness points fixed in place. The result is that you expand the range and condense the fuzziness, or vice versa.

Drag the triangular fuzziness control to lengthen or contract the fuzziness independently of the color range.

Tip

By default, red is the central color in the color ramps, with blue at either side. This is great when the range is red or some other warm color. But if you're working with a blue range, the controls get split between the two ends. To move a different color to the central position, Ctrl-drag (Win) or

Eyedroppers: To lift a color range from the image window, click inside the image window with the Eyedropper cursor. The cursor automatically changes to an eyedropper when you move it outside the Hue/Saturation dialog box, and then when you click on a color, Photoshop centers the range on the exact color you click.

Tip

To expand the range to include more colors, Shift-click or drag in the image window. To remove colors from the range, Alt-click (Option-click on the Mac) or drag in the image. You also can use the alternative plus and minus Eyedropper tools, but Shift and Alt (Shift and Option on the Mac) work well, too.

Load/Save: You can load and save settings to disk in case you want to reapply the options to other images using the Load/Save options. These options are especially useful if you find a magic combination of color-correction settings that accounts for most of the color mistakes produced by your scanner.

Colorize: Select this option to apply a single hue and a single saturation level to the entire selection or layer, regardless of how it was previously colored. All brightness levels remain intact, although you can adjust them incrementally using the Lightness slider bar (a practice that should be avoided, as mentioned earlier).

Color ranges are not permitted when colorizing. The moment you select the Colorize option, Photoshop dims the Edit pop-up menu and sets it to Master.

Restore: Wait — there's no Restore button in this dialog box. Or is there? If you Alt-click (Windows) or Option-click (Mac) the Cancel button, it becomes a Restore button. While in Restore mode, you can restore the options in the Hue/Saturation, Levels, and Curves dialog boxes to their original settings by clicking Restore. You also can press Option+Escape on the Mac to achieve the same result.

To track the behavior of specific colors when using Hue/Saturation or any of Photoshop's other powerful color adjustment commands, display the Info palette (press F8) before choosing the Hue/Saturation command. Then move the cursor inside the image window. As shown in Figure 18.12, the Info palette tracks the individual RGB and CMYK values of the pixel beneath the cursor. The number before the slash is the value before the color adjustment; the number after the slash is the value after the adjustment. Note that the Info palette shows these before and after numbers only while the adjustment dialog box is open; if you're just sampling pixels with the Eyedropper, there is only one value shown in the palette — the color values for the pixel you're sampling at the time.

Note

Photoshop's Histogram palette also updates continuously as you work in the Hue/Saturation dialog box or with any of the other color adjustment commands. The Histogram palette is discussed a little later in this chapter.

Remember that you don't have to settle for just one color readout. Shift-click in the image window to add up to four fixed color samples, just like those created with the color sampler tool, described in Chapter 4. To move a color sample after you've set it in place, Shift-drag it.

In the case of the Hue/Saturation dialog box, you can set color sample points only when the Edit pop-up menu is set to Master. After you set the samples, select some other options from the pop-up menu to modify a specific range. As long as you select only the Master option and edit only the Hue value, Photoshop retains all colors in an image. In other words, after shifting the hues in an image +60 degrees, you can later choose Hue/Saturation and shift the hues −60 degrees to restore the original colors.

Note

Just as the Saturation option works like the Color control on a television, the Hue value serves the same purpose as the Tint control, and the Lightness value works like the Brightness control. Note that increasing the Saturation has the effect of heightening the contrast of the color channels, so display the Channels palette before opening the Hue/Saturation dialog box and display just one channel. Watch as you drag the Saturation slider, and then switch channels to see the impact on each one individually. You have to close the dialog box to switch channels though.

Tip

The Saturation option is especially useful for toning down images captured with low-end scanners and digital cameras, which have a tendency to exaggerate certain colors.

Figure 18.12. When you move the Eyedropper outside a color adjustment dialog box and into the image window, the Info palette lists the color values of the pixel beneath the cursor before and after the adjustment.

Another common use for the Saturation option is to prepare RGB images for process-color printing. As explained in Chapter 4, many colors in the RGB spectrum are considered out-of-gamut, meaning that they fall outside the smaller CMYK color space. Photoshop provides a means for recognizing such colors while remaining inside the RGB color space. Choose View

How do you eliminate these out-of-gamut colors? Consider these options:

Let Photoshop take care of the problem automatically when you convert the image by choosing Image

Another method is to scrub with the Sponge tool. Although it theoretically offers selective control — you just scrub at areas that need attention until the gray pixels created by the Gamut Warning command disappear — the process leaves too much to chance and can do more damage than simply choosing Image

The third and best solution involves the Saturation option in the Hue/Saturation dialog box.

If you're surprised to read the last item (and wondering why it's listed last if it's the best bet), don't be; read on for a procedure you can try to bring your colors back into the CMYK color space.

STEPS: Eliminating out-of-gamut colors

Create a duplicate of your image to serve as a CMYK preview. Choose Image

Return to your original image, and choose Select

To monitor your progress, choose View

Press Ctrl+U (

+U on the Mac) to display the Hue/Saturation dialog box.

Lower the saturation of individual color ranges. Don't change any settings while Master is selected; it's not exacting enough. Instead, experiment with specifying your own color ranges and lowering the Saturation value. Every time you see one of the pixels change from gray to color, it means that another pixel has now left the "out of gamut" ranks and is officially within the CMYK color space.

When only a few hundred sporadic gray spots remain onscreen, click OK to return to the image window. Choose Image

Bear in mind that the differences between your duplicate image and the one you manually forced into gamut may be very subtle and you may not really notice any immediate improvement. When the image is printed, however, the difference is more obvious and produces a better-looking image with a more dynamic range of colors.

The one problem with the previous procedure is that the Color Range command selects only out-of-gamut pixels without even partially selecting their neighbors. As a result, you desaturate out-of-gamut colors while leaving similar colors fully saturated, an effect that may result in jagged and unnatural edges.

One solution is to insert a step between Steps 2 and 3 in which you do the following: Select the Magic Wand tool, and change the Tolerance value in the Options bar to 12, for example (feel free to tinker). Next, choose Select

This solution isn't perfect — ideally, the Color Range option box wouldn't dim the Fuzziness slider when you choose Out Of Gamut — but it does succeed in partially selecting a few neighboring pixels without sacrificing too many of the out-of-gamut pixels, and makes for a smoother result.

When you select the Colorize option in the Hue/Saturation dialog box, the options perform differently. Every pixel in the selection receives the same hue and the same level of saturation, and only the brightness values remain intact to ensure that the image remains recognizable. In most cases, you'll want to colorize only grayscale images or bad color scans. After all, colorizing ruins the original color composition of an image. For the best results, you'll want to set the Saturation values to somewhere in the neighborhood of 25 to 75.

Tip

To touch up the edges of a colorized selection, change the foreground color to match the Hue and Saturation values you used in the Hue/Saturation dialog box. You can do this by choosing the HSB Sliders command from the Color palette menu and typing the values in the H and S option boxes. Set the B (Brightness) value to 100 percent. Next, select the Brush tool and change the Brush mode to Color by pressing Shift+Alt+C (Shift+Option+C on the Mac).

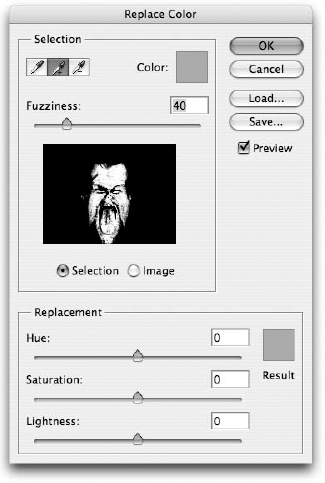

The Replace Color command allows you to select an area of related colors and adjust the hue and saturation of that area. When you select Image

For further comfort or confusion (however the similarities with other tools strike you), this dialog box works the same as selecting a portion of an image using Select

So given that the Replace Color command's dialog box looks and acts like two other tools, why does it even exist? Because it allows you to change the selection outline and apply different colors without affecting the image. Just select the Preview option to see the results of your changes onscreen, and you can play with the settings and click OK only when you like what you see.

Note

If you're not clear on how to use all the options in the Replace Color dialog box, read the section in Chapter 9 on using the Color Range command. The content there tells you all about the Eyedropper tools and the Fuzziness option so you'll have a better idea of how they work.

Figure 18.13. The Replace Color dialog box works like the Color Range dialog box described in Chapter 9, with the Hue/Saturation sliders thrown in.

The Selective Color command permits you to adjust the colors in CMYK images. Although you can use Selective Color also when working on RGB or Lab images, it makes more sense in the CMYK color space because it permits you to adjust the levels of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black inks.

Note

You may find that the Variations command provides better control and more intuitive options than the Selective Color command. Adobe created the Selective Color command to accommodate traditional press managers who prefer to have direct control over ink levels rather than monkeying around with hue, saturation, and other observational color controls. If Selective Color works for you, great. But don't get hung up on it if it never quite gels. You can accomplish all that Selective Color provides and more with the Variations command, described in the next section.

Choosing Image

If you examine the Selective Color dialog box closely, you'll notice that it is very much like the Hue/Saturation dialog box. You have access to predefined colors in the form of a pop-up menu instead of radio buttons, and you can adjust slider bars to alter the color. The two key differences are that the pop-up menu lets you adjust whites, medium grays (Neutrals), and blacks — options missing from Hue/Saturation — and that the slider bars are always measured in the CMYK color space.

Tip

As mentioned at the outset, the Selective Color command produces the most predictable results when you're working on a CMYK image. When you drag the Cyan slider to the right, for example, you're actually transferring brightness values to the cyan channel. However, you have to keep an eye out for a few anomalies, particularly when editing black. In the CMYK mode, areas of your image that appear black include not only black but also shades of cyan, magenta, and yellow, resulting in what printers call a rich black (or saturated black). Therefore, to change black to white, you have to set the Black slider to −100 percent and also set the Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow sliders to the same value.

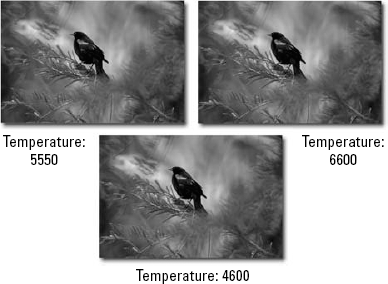

Since the dawn of color film, photographers have used different filters and balanced film stocks to correct the color balance in their photos. Different types of light sources produce a variety of color temperatures: Natural daylight generally takes on a bluish cast, or a higher color temperature, whereas artificial light often produces more shades of reds and yellows, or a lower color temperature. When not shooting on film that has been prebalanced to account for these casts, photographers often place a color filter over the lens to compensate — adding blue to an indoor scene to counteract the yellows, for example. It's similar to how folks who work in video need to set the white balance on their cameras before they shoot.

Figure 18.14. Select a predefined color from the Colors pop-up menu, and adjust the slider bars to change that color.

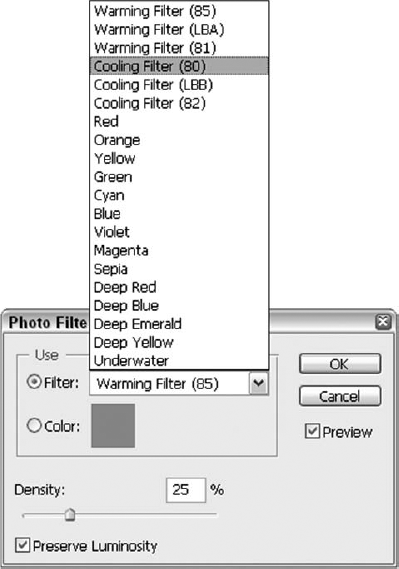

Although it has long let you correct the colorcast of an image through Variations (which is discussed next), Photoshop also offers a handy tool through the Photo Filter command. Choose Image

Filter: The Filter pop-up menu includes six specific filter options followed by a list of colors you can use to fix various colorcasts on your image. The first three options, Warming Filter (85), Warming Filter (LBA) and Warming Filter (81), simulate filters that a photographer would use when the color temperature is too cool, or bluish. Warming Filter (85) produces an orange colorcast, and Warming Filter (81) adds more of a tan tint to your image. Conversely, Cooling Filter (80), Cooling Filter (LBB) and Cooling Filter (82) add to your image a dark and rich cast of blue or a light cast of blue, respectively, to account for the yellows of artificial light. The rest of the options in the pop-up menu are different color presets that let you achieve photographic effects similar to those provided by some real-life filters.

Color: You also can specify any color and use it as though it were a filter. This is a great way to compensate for an unusual colorcast, such as a color light source in a scene that you'd like to neutralize. Click the color swatch to open the Color Picker, and select a color. Alternatively, after the Color Picker is open, you can click anywhere in your image to choose a particular color.

Density: The Density slider adjusts the amount of color correction that the Photo Filter command will apply. You also can manually type a value in the option box above the slider. Remember that you can always adjust the amount of correction after you click OK by choosing Edit

Preserve Luminosity: Select this option to ensure that the brightness values are not darkened by your color adjustments.

Tip

You also can apply the Photo Filter command as an adjustment layer, ensuring that none of the changes you make is permanent. You'll take a look at adjustment layers later in this chapter.

The Variations command is Photoshop's most essential color-correction function and its most un-Photoshop-ish in that it's amazingly simple and highly effective all at the same time. Typically, control comes with complexity, but not so here.

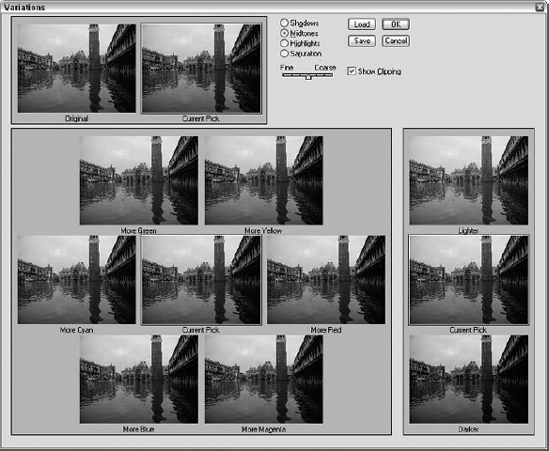

When it comes to control and effectiveness, you can adjust hues and luminosity levels based on the brightness values of the pixels, something Hue/Saturation cannot do. You also can see what you're doing by clicking little thumbnail previews, shown in Figure 18.16, which takes much of the guesswork out of the correction process. This is where the "alarmingly simple" description comes in.

On the other hand, the Variations dialog box takes over your screen and prevents you from previewing corrections in the image window — not a big deal, but if you're used to seeing a preview in the image window, this can be jarring. Another problem (equally slight, really) is that you can't see the area outside a selection, which can be disconcerting when making color adjustments to just part of your image. You won't know until you click OK if the adjustment you made to the selection works in context, but you can slide the dialog box aside to see the entire original image. Just click the title bar of the dialog box and drag it.

The Variations command is really great for correcting an image in its entirety, although it can be useful for adjusting selections (with the previously mentioned issues kept in mind). Whether you like it for the whole image or just part of it, here's how it works: To infuse color into the image, click one of the thumbnails in the central portion of the dialog box. The thumbnail labeled More Cyan, for example, shifts the colors toward cyan. The thumbnail even shows how the additional cyan will look when added to the image. You can also use the Lighter and/or Darker thumbnails to adjust the overall light levels in your image or a selected portion thereof.

Notice that each of the color thumbnails is positioned directly opposite its complementary color, with the Current Pick between them. More Cyan is across from More Red, More Blue is across from More Yellow, and so on. In fact, clicking a thumbnail shifts colors not only toward the named color but also away from the opposite color. For example, if you click More Cyan and then click its opposite, More Red, you arrive at the original image.

Note

Although this isn't exactly how the colors in the additive and subtractive worlds work — cyan is not the empirical opposite of red — the colors are theoretical opposites, and the Variations command makes the theory a practicality. After all, you haven't yet applied the color to the image, so the dialog box can calculate its adjustments in a pure and perfect world. Cyan and red ought to be opposites, so for the moment, they are.

To control the amount of color shifting that occurs when you click a thumbnail, move the slider in the upper-right corner of the dialog box. Fine produces minute changes; Coarse creates massive changes. Just to give you an idea of the difference between the two, you have to click a thumbnail about 40 times when the slider is set to Fine to equal one click when it's set to Coarse.

Figure 18.16. Click the "More" thumbnails to add more of one color or another to your image. Refer to the Current Pick to see your results before okaying them. Start over by clicking the Original thumbnail, and use the radio buttons to choose which aspect of the image to change. The slider adjusts sensitivity.

The radio buttons at the top control which colors in the image are affected. Select Shadows to change the darkest colors, Highlights to change the lightest colors, and Midtones to change everything in between.

Note

In fact, if you're familiar with the Levels dialog box, you may have noticed that the first three radio buttons have direct counterparts in the sliders in the Levels dialog box. For example, when you click the Lighter thumbnail while the Highlights option is selected in the Variations dialog box, you perform the same action as moving the white slider in the Levels dialog box to the left — that is, you make the lightest colors in the image even lighter.

Selecting the Saturation option lets you increase or decrease the saturation of colors in an image. Only one thumbnail appears on each side of the Current Pick image: one that decreases the saturation and another that increases it. The Variations command modifies saturation differently than Hue/Saturation. Hue/Saturation pushes the saturation of a color as far as it will go, but Variations attempts to modify the saturation without changing overall brightness values. As a result, an image saturated with Hue/Saturation looks lighter than one saturated with Variations.

As you click the options — particularly when modifying saturation — you may notice that unexpected colors spring up in the thumbnails. These brightly colored pixels are gamut warnings, highlighting colors that exceed the boundaries of the current color space. For example, if you're working in the RGB mode, these colors extend beyond the RGB gamut. Although the colors won't actually appear inverted as they do in the dialog box, don't exceed the color space because it results in areas of flat color, just as when you convert between the RGB and CMYK spaces. To view the thumbnails without the weirdly colored pixels, deselect the Show Clipping option.

With Adobe's introduction of the Match Color command in Photoshop CS, the Photoshop user community wondered if Adobe had really added a true color-matching tool. Well, even with the release of Photoshop CS2 and now CS3, the answer was and is no, and the wait continues: The Match Color command has nothing to do with emulating the color of a match. It does, however, adjust the colorcast of one image to match that of another, which can still be pretty useful.

In case you were wondering how such a tool might be useful, imagine that you have a series of photos taken outdoors, on a day when the sun was coming in and out over the course of your shoot and the lighting was really different in several of the shots. Or you were taking photos of people indoors, and in the later afternoon, when the room got hotter, people started to look a bit flushed, or the sunlight coming into the room was starting to change and it no longer drowned out the fluorescent lighting from overhead in the room. Any of these scenarios would present you with the need to change a colorcast, making one photo's cast match another's. Brighten the cloudy photos, smooth out the ruddy cheeks, soften the pasty fluorescent glow.

You begin by opening both the image you want to adjust and the image whose color you want to match. If you want Match Color to base its analysis on a particular part of the image, such as skin tones, select the colors you want to isolate in both the source and destination images. Make sure the destination image is in the active image window and choose Image

The following list explains the options available to you in the Match Color dialog box:

Target: The Target is automatically set as whatever image was active when you chose the command, and you can't change this. If your destination image contains a selection, the Ignore Selection when Applying Adjustment option is available. If you don't select this option, the effect applies only to the selected area in your image, which may not be the desired result. If you've made a selection in your destination image and you don't want to confine the effect to that selection, select the option.

Image Options: The Image Options let you make adjustments to the lightness, saturation, and strength of the Match Color command. The Luminance slider defaults to a value of 100 and lets you increase or decrease the brightness of your destination image. Color Intensity works much like the Saturation slider in the Hue/Saturation command. The Fade slider saves you the step of applying Match Color and then choosing Edit

Tip

Select the Neutralize option to tell Photoshop to examine the destination image, without factoring in any values from the source image, and attempt to remove any colorcast that it finds. You may find that sometimes it works really well and sometimes it just dulls your image. If you don't get the results you want, try using the Photo Filter command or the Variations dialog box, discussed earlier in this chapter, to manually target and correct a colorcast.

Image Statistics: These options let you specify a source image and determine how it is interpreted. The source can be any other open image, or even a layer within the destination image itself. The latter is particularly useful if, for example, you're trying to composite a person from another photo on a separate layer into your destination image. If your source image contains a selection, select the Use Selection in Source to Calculate Colors option to only analyze the statistics, or characteristics, of the selected region. When this option is deselected, Match Color determines the statistics of the source by looking at all the pixels in the image. Similarly, selecting the Use Selection in Target to Calculate Adjustment option makes changes to the target image using colors found in only the selected area of that image. If you selected similarly colored areas in both your target and source images, leave both of these options selected.

Use the Source pop-up menu to choose the source image from among all open images. If you select None, you still have access to the Neutralize option and other Image Options settings. If you select a source with more than one layer, you can specify the layer from which you're culling statistics in the Layer pop-up menu. You also have the option of choosing a merged composite of all the layers in the source image.

Finally, the Match Color dialog box offers you the option of both saving and then loading the statistics it has calculated from a source image. This can be useful in a couple of ways. First, it means you don't need to have a source image open when applying the Match Color command. It also means that you can save the statistics of an image and use them to adjust an unlimited number of other images, on other machines, long after the original source image is out of the picture.

Note

The Match Color command works only with images in the RGB mode.

Now that you know several methods for adjusting hues and saturation levels with Photoshop, we want to discuss some of the possible challenges you may face in using them. The danger of rotating colors or increasing the saturation of an image is that you can bring out some unstable colors. Adjusting the hues can switch ratty pixels from colors that your eyes aren't very sensitive to — particularly blue — into colors your eyes see very well, such as reds and greens. Drab color also can hide poor detail, which becomes painfully obvious when you make the colors bright and vivid; all the problems in the image will come screaming out at you after you've heightened the colors.

Unstable colors may be the result of JPEG compression, as in the case of the digital photo. Or you may be able to blame bad scanning or poor lighting; the potential causes are abundant, and we've all been victims. No matter what's caused your color problems, you can correct the problem using the Median and Gaussian Blur commands, explained in the following procedure. Grab a particularly color-challenged digital photo and try the following:

STEPS: Boosting the saturation of digital photos

Select the entire image, and copy it to a new layer. You can speed this process along with the keyboard shortcuts Ctrl+A and Ctrl+J (

Press Ctrl+U (

Choose Filter

Choose Filter

Select Color from the blend mode pop-up menu in the Layers palette. Photoshop mixes the blurry color with the crisp detail underneath.

If your image is still a little soft, flatten the image and sharpen it until you like the results.

Note

Take a little refresher on those Blur, Sharpen, and Noise filters in Chapter 10.

You may find the Lighter and Darker options in the Variations dialog box to be more effective and controllable than the Lightness slider in the Hue/Saturation dialog box because you can specify whether to edit the darkest, lightest, or medium colors in an image. Focusing on these areas gives you the ability to target trouble spots, which is handy if not all of your pixels are in need of lighting adjustment. If your needs are even more specific, you may find that neither command is adequate for making very precise adjustments to the brightness and contrast of an image. If this is the case, Photoshop provides three expert-level commands for adjusting the brightness levels in both grayscale and color images:

Levels: This command is great for most color corrections. It lets you adjust the darkest values, lightest values, and midrange colors with a minimum of complexity and a maximum amount of control.

Curves: This command is great for creating special effects and correcting images beyond the help of the Levels command. Levels didn't really do it all? Using the Curves command, you can map every brightness value in every color channel to an entirely different brightness value. Hop from channel to channel, and let Curves work its magic until you're happy with the results.

Shadow/Highlight: This command is great for altering the brightness levels of certain sections of an image without harming other sections. It provides for a different approach than the Levels command and is particularly good at fixing backlighting problems in images.

Note

As with any application with a large number of fevered devotees, Photoshop's two brightness commands, Levels or Curves, have spurred some debates as to which is the more effective. Levels, it has been argued, provides a histogram, which is thought to be absolutely essential for gauging the proper setting for black and white points. Not to be outdone, Curves lets you map out a virtually infinite number of significant points on a graph. Of course, with Photoshop CS came the Histogram palette, and it remains a powerful weapon in Photoshop CS3. No longer confined to the Levels dialog box, the mighty histogram is right there under the Info and Navigator tabs in a shared palette. Every user and every user's photo will have special needs, and no one tool will serve or please them all — at least not all the time. Is there really a best here? Probably not.

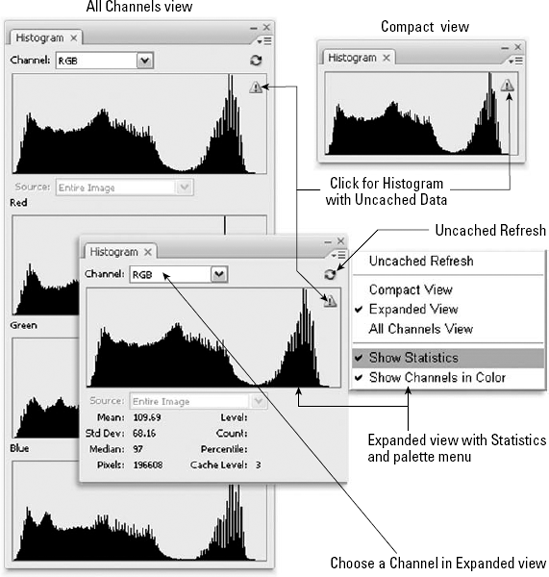

As discussed earlier in the section on the Threshold command, a histogram is a graph depicting the intensity of different values in your image. While the histogram in the Threshold command displays only brightness values, the Histogram palette is capable of showing not only the brightness values but the combined color values and the individual color values in an image as well. Keep the palette onscreen, and you're never more than a quick look away from knowing the distribution of levels in your image at any given time.

Choose Window

The expanded view is where you can explore the real power of the Histogram palette. It contains the following options:

Channel: The Channel pop-up menu lets you determine the types of values displayed by the Histogram palette. By default, it's set to the color mode in which you're working. If you're editing an image in either the Grayscale or Indexed Color modes, this menu is unavailable.

From the Channel menu, you can choose to display the default combined tonal levels or any of the color channels individually. Choose Show Channels in Color from the palette menu to display the individual channels in the colors they represent. Any additional channels you have created also can be selected from the Channel pop-up menu. Choose Luminosity to display a histogram of only the brightness levels in your image. Finally, you can call up an overlapping composite graph of all the color channels by choosing Colors.

Uncached Refresh: Whenever you make an adjustment to an image that affects its brightness or color intensity levels, the histogram redraws itself to compensate. It saves time doing this by analyzing the already existing cache of the image and guessing how the change you've made will affect the graph. The Preferences setting that enables the Levels command to use the image cache is covered in Chapter 2.

Regardless of how you've set your preferences, the Histogram palette automatically regenerates based on the image cache unless you click Uncached Refresh (labeled in Figure 18.18), which tells the palette to redraw the graph based on the current image. Photoshop provides a number of other ways to refresh the histogram. You also can click the cached data warning icon (labeled in Figure 18.18) that appears in the top-right corner of the histogram whenever you're viewing a graph created from the cache. Additionally, you can accomplish the same thing by doubling-clicking the histogram itself. Finally, you can choose the Uncached Refresh option from the palette menu.

Source: In a multilayered image, you can tell the Histogram palette to display values for either the Entire Image or just the Selected Layer from the Source pop-up menu. If the image contains any adjustment layers, select one of them and choose Adjustment Composite from the Source pop-up menu to display a histogram of the adjustment layer and any visible layers below it.

Below the Source menu in the expanded view, you'll find statistical information about the image or layer, which you can toggle on or off by choosing Show Statistics from the palette menu. The statistics give you some useful information about the intensity values in your image, plus you can find out about the intensity Level at the spot under your cursor. You also can view the Count, which tells you the total number of pixels in the image that match a particular intensity.

One of the great strengths of the Histogram palette is the fact that it updates on the fly even while you're working in one of the color adjustments dialog boxes (but only if you have selected the Preview option). Even better, the palette doesn't simply replace the original histogram with the new one; it keeps the original histogram visible behind the adjusted histogram in a grayed-out version.

Tip

When you select a portion of an image, the Histogram palette displays intensity levels and statistics for only the selected area.

Although many of the other palettes become frozen when you're working in a dialog box, you never lose access to the options in the Histogram palette — given that it is used in conjunction with so many of them. One exception? You can't access the Histogram palette options when the Filter Gallery window is open.

Oh, and don't panic if you go to the palette and see a circle with a line through it where the histogram should be: This is simply what's displayed when there is no image open in the Photoshop workspace.

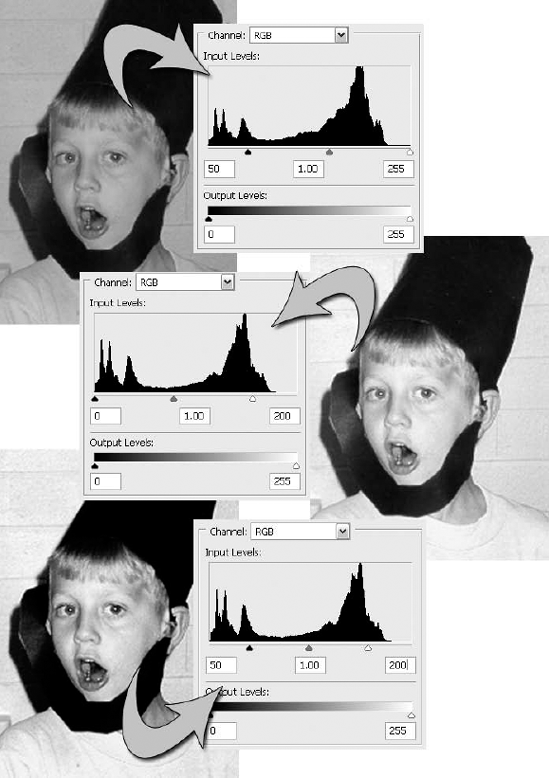

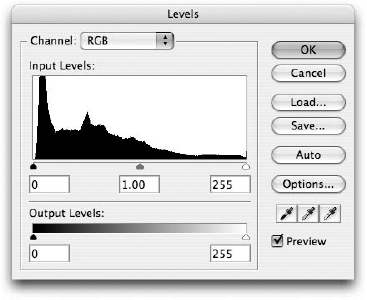

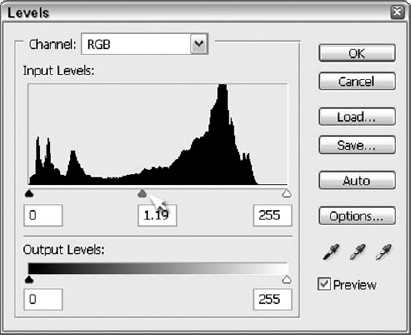

When you choose Image

Figure 18.19. Use the Levels dialog box to map brightness values in the image (Input Levels) to new brightness values (Output Levels).

The options in the Levels dialog box work as follows:

Channel: Select the color channel that you want to edit from this pop-up menu. You can apply different Input Levels and Output Levels values to each color channel.

Input Levels: Use these options to modify the contrast of the image by darkening the darkest colors and lightening the lightest ones. The Input Levels option boxes correspond to the slider immediately below the histogram. You map pixels to black (or the darkest Output Levels value) by typing a number from 0 to 255 in the first option box or by dragging the black slider. For example, if you raise the value to 50, all colors with brightness values of 50 or less in the original image become black, darkening the image as shown in the first example of Figure 18.20.

You can map pixels at the opposite end of the brightness scale to white (or the lightest Output Levels value) by typing a number from 0 to 255 in the last option box or by dragging the white slider. If you lower the value to 200, all colors with brightness values of 200 or greater become white, lightening the image, as shown in the second example of Figure 18.20. In the last example of the figure, the first value was raised and the last value lowered, thereby increasing the amount of contrast in the image.

Tip

The Input Levels value is to select the numeric field and then press the up-arrow or down-arrow key. Each press of an arrow key raises or lowers the value by 1. Press Shift with an arrow key to change the value in increments of 10.

Tip

If you press and hold Alt (Option on the Mac) while dragging the black and white Input Levels sliders, you can watch where the first shadows appear and where the first highlight detail begins in your RGB image.

Gamma: The middle Input Levels option box and the corresponding gray triangle in the slider bar (shown in Figure 18.21) represent the midtone, or gamma value, which is the brightness level of the medium-gray value in the image. The gamma value can range from 0.10 to 9.99, with 1.00 being dead-on medium gray. Increase the gamma value or drag the gray slider to the left to lighten the medium grays (also called midtones). Lower the gamma value or drag the gray slider to the right to darken the medium grays.

Figure 18.21. The middle slider under the Histogram controls midtones. Drag it to adjust the middle box, or type a new number in the middle of the three Input Levels boxes and see the slider move to indicate the new midtone level.

Tip

You also can edit the gamma value by pressing the up-arrow and down-arrow keys. Pressing an arrow key changes the value by 0.01; pressing Shift+arrow changes the value by 0.10.

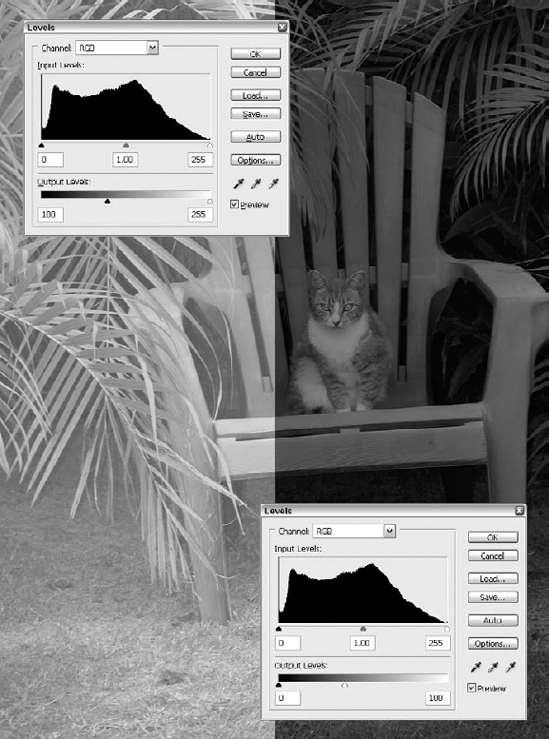

Output Levels: Use these options to curtail the range of brightness levels in an image by lightening the darkest pixels and darkening the lightest pixels. You adjust the brightness of the darkest pixels — those that correspond to the black Input Levels slider — by typing a number from 0 to 255 in the first option box or by dragging the black slider. For example, if you raise the value to 100, no color can be darker than that brightness level (roughly 60 percent black), which lightens the image. You adjust the brightness of the lightest pixels — those that correspond to the white Input Levels slider — by typing a number from 0 to 255 in the second option box or by dragging the white slider. If you lower the value to 175, no color can be lighter than that brightness level (roughly 30 percent black), darkening the image. If you raise the first value and lower the second value, you dramatically decrease the amount of contrast in the image. Note that any change to the Output Levels values decreases the contrast of the image. Figure 18.22 shows two halves of the same image: The left half has darks made lighter, and the right half has lights made darker.

Tip

You can fully or partially invert an image using the Output Levels slider triangles. Just drag the black slider to the right and drag the white slider to the left past the black slider. The colors flip, whites mapping to dark colors and blacks mapping to light colors.

Load and Save: You can load settings to disk and save settings to disk using these buttons.

Auto: You might assume that the Auto button in the Levels dialog box performs the same function as the Auto Levels command, discussed earlier in this chapter. And if you were working in a version of the program before Photoshop 7, you'd be right. Photoshop 7, however, added the Options button into the mix. Since then, the effect of clicking Auto in the Levels dialog box (as well as in the Curves dialog box) has depended on the settings in the Auto Color Correction Options dialog box, described next.

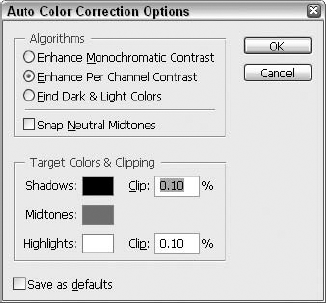

Options: Clicking Options in the Levels (or Curves) dialog box brings up the Auto Color Correction Options dialog box, shown in Figure 18.23. The top section, Algorithms, determines the type of correction you want to apply. Instead of the long, somewhat confusing names, these three choices could be labeled Auto Contrast, Auto Levels, and Auto Color, because that's what the choices are equivalent to. In fact, you can rest your cursor over each name to see an informative tool tip telling you just this. Select the Snap Neutral Midtones option, and you'll apply Auto Color's automatic gamma correction as well. If you select the Save as Defaults option, your settings are remembered the next time you click Auto in the Levels and Curves dialog boxes.

The Target Colors & Clipping settings come into play not only when you click Auto in the Levels and Curves dialog boxes but also when you choose the Auto Levels and Auto Contrast commands in the Adjustments submenu. (This is assuming that Save as defaults check box is selected.) Here you can choose colors to assign to the target values for the highlights, midtones, and shadows in your image. You also have access to the Clip values for the highlights and shadows. Type higher values to increase the number of pixels mapped to black and white; decrease the values to lessen the effect. Figure 18.24 compares the effect of the default 0.50 percent values to higher values of 5.00 and 9.99 percent (the highest setting the field accepts). As you can see, raising the Clip value produces higher contrast effects.

Figure 18.22. Lighten your darks and darken your lights, and you'll get something like these results of raising the first Output Levels value to 100 (left) and lowering the second value to 175.

Figure 18.23. Customizing the settings in the Auto Color Correction Options dialog box lets you take the "auto" out of Photoshop's auto correction commands.

Note

The Clip settings have an effect only on Auto Levels and Contrast, not Auto Color. The reason is that Auto Color seeks to neutralize shadows and highlights, as opposed to clipping away the darkest and lightest colors.

Tip

You can combine the Auto Color Correction Options with the Auto Color command to create a truly useful tool. If you have a batch of photos you need to correct that share similar problems — maybe you've scanned an overexposed roll of film from a recent holiday — make adjustments to the first photo with the Target Colors & Clipping settings and make sure you select the Save as defaults option. Now when you open subsequent photos, you can simply choose Image

Eyedroppers: Select one of the Eyedropper tools in the Levels dialog box and click a pixel in the image window to automatically adjust the color of that pixel. If you click a pixel with the black Eyedropper tool (the first of the three), Photoshop maps the color of the pixel and all darker colors to black. If you click a pixel with the white Eyedropper tool (the last of the three), Photoshop maps it and all lighter colors to white. Use the gray Eyedropper tool (middle) to change the color you clicked to medium gray and adjust all other colors accordingly.

Tip

One way to use the Eyedropper tools is to color-correct scans without lots of messing around. Include a neutral swatch of gray with the photograph you want to scan. (For those who own a Pantone swatch book, Cool Gray 5 or 6 is your best bet.) After opening the scan in Photoshop, choose the Levels command, select the gray Eyedropper tool, and click the neutral gray swatch in the image window. This technique doesn't perform miracles, but it helps you distribute lights and darks in the image more evenly. You then can fine-tune the image using the Input Levels and Output Levels options.

Figure 18.24. This figure shows the effect of the default Clip values in the Auto Color Correction Options dialog box (.50% on the left) and the effect after raising the values (5.00% in the middle and 9.99% on the right).

Tip

By default, the Eyedroppers map to white, gray, and black. But you can change that. Double-click any one of the three Eyedroppers to display the Color Picker dialog box. For example, suppose you double-click the white Eyedropper, set the color values to C:2, M:3, Y:5, K:0, and then click a pixel in the image window. Instead of making the pixel white, Photoshop changes the clicked color — and all colors lighter than it — to C:2, M:3, Y:5, K:0, which is great for avoiding hot highlights and ragged edges.

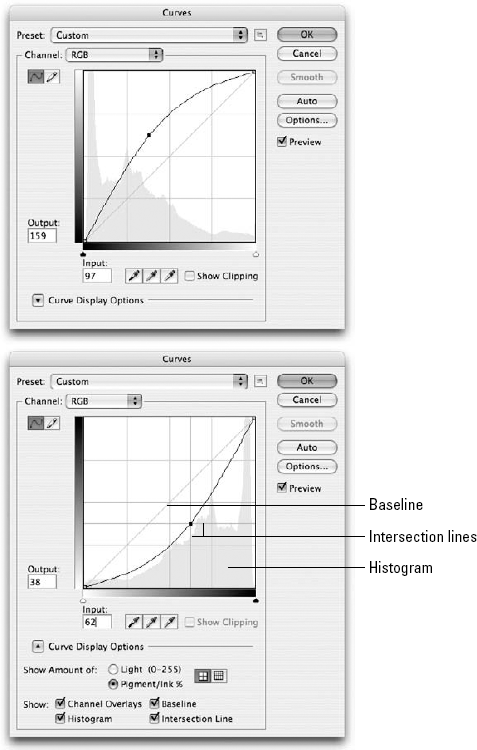

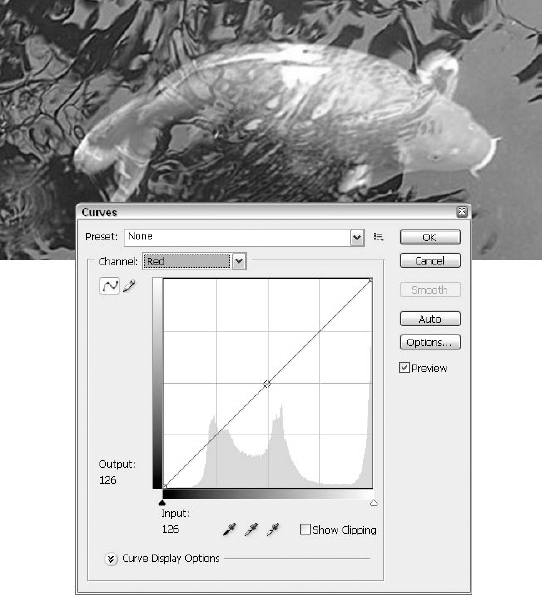

If you want to be able to map any brightness value in an image to absolutely any other brightness value, the Curves command is what you need. When you choose Image

Here's a quick sketch of how the Curves dialog box options work:

Channel: The concept of channels isn't new, certainly, and the use of channels within an adjustment dialog box is nothing new in the case of Curves either. You select the color channel that you want to edit from this pop-up menu, and then apply different mapping functions to different channels by drawing in the graph below the pop-up menu. Of course, as always, the options along the right side of the dialog box affect all colors in the selected portion of an image regardless of which Channel option is active.

Brightness graph: The brightness graph is where you map brightness values in the original image to new brightness values. The horizontal axis of the graph represents input levels; the vertical axis represents output levels. The brightness curve charts the relationship between input and output levels. The lower-left corner is the origin of the graph (the point at which both input and output values are 0). Move right in the graph for higher input values and up for higher output values. The brightness graph is the core of this dialog box, so upcoming sections explain it in more detail.

Tip

By default, a grid of horizontal and vertical dotted lines crisscrosses the brightness graph, subdividing it into quarters. For added precision, you can divide the graph into horizontal and vertical tenths by Alt-clicking (Win) or Option-clicking (Mac) in the graph to toggle between tenths and quarters.

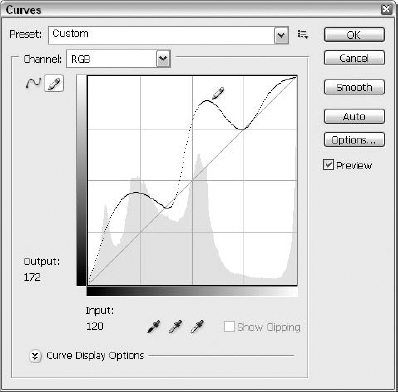

Brightness bar: The horizontal brightness bar shows the direction of light and dark values in the graph. When the dark end of the brightness bar appears on the left — as by default when editing an RGB image — colors are measured in terms of brightness values. The colors in the graph proceed from black on the left to white on the right, as demonstrated in the left example of Figure 18.26. Therefore, higher values produce lighter colors. This setting measures colors in the same direction as the Levels dialog box.

This dialog box has seen some changes in CS3. In previous versions of Photoshop, you clicked the brightness bar to toggle the view between brightness values and ink coverage. Adobe has extended the interface here, so this option is a little more obvious. The bottom portion of the dialog box now presents the Curve Display Options button. By clicking this, you gain access to radio buttons that toggle the view between Light and Pigment/Ink. You also have check boxes that allow you to show the channel overlays, histogram, baseline, and intersection lines. If you select Pigment/Ink, white and black switch places on the brightness bar, as shown in the second example of the figure, and the dialog box then measures the colors in terms of ink coverage, from 0 to 100 percent of the primary color. Higher values now produce darker colors. This is the default setting for grayscale and CMYK images.

Curve tools: Use the Curve tools to draw the curve in the brightness graph. The Point tool (labeled in Figure 18.27) is selected by default. Click in the graph with this tool to add a point to the curve. Drag a point to move it. To delete a point, Ctrl-click (Win) or

The Pencil tool lets you draw free-form curves simply by dragging in the graph, as illustrated in Figure 18.27. This pencil works much like Photoshop's standard Pencil tool, in that you can draw straight lines by clicking one location in the graph and Shift-clicking a different point.

Input and Output values: The Input and Output values monitor the location of your cursor in the graph according to brightness values or ink coverage, depending on the setting of the brightness bar. You can modify the Input and Output values when working with the Point tool. Just click the point on the graph that you want to adjust and then type new values. The Input number represents the brightness or ink value of the point before you entered the Curves dialog box; the Output number represents the new brightness or ink value.

When editing multiple graph points from the keyboard, you may want to activate the points from the keyboard. To advance from one point to the next, press Ctrl+Tab (Control+Tab on the Mac). To select the previous point, press Ctrl+Shift+Tab (Control+Shift+Tab on the Mac). To deselect all points, press Ctrl+D (

Tip

You also can change the Output value by using the up-arrow and down-arrow keys. Click the point you want to modify, and then press the up-arrow or down-arrow key to raise or lower, respectively, the Output value in increments of 1. Press Shift+up arrow or down arrow to change the Output value in increments of 10. Note that these techniques — and the ones that follow — work only when the Point tool is active because you can't change points with the Pencil tool.

Load and Save: Use these buttons to load and save curve settings to disk, respectively.

Smooth: Click Smooth to smooth out curves drawn with the Pencil tool. Doing so leads to smoother color transitions in the image window. This button is dimmed unless the Pencil tool is active.

Auto: This button is identical to the Auto button available in the Levels dialog box: It allows you to apply, automatically, the settings you can establish in the Options dialog box (opened by clicking Options, discussed in the next paragraph) when Auto is clicked. For more details on this concept, see the section "The Levels command" earlier in this chapter; the Levels dialog box has an Auto button too.

Options: Identical to the Options button in the Levels dialog box, this opens the Auto Color Correction dialog box, wherein you can set the Target Colors & Clipping settings discussed in the Levels command coverage earlier in this chapter. Whatever you set in this dialog box is applied by the aforementioned Auto button.

Eyedroppers: If you move the cursor out of the dialog box and into the image window, you get the standard eyedropper cursor. Click a pixel in the image to locate the brightness value of that pixel in the graph. A circle appears in the graph, and the Input and Output numbers list the value for as long as you hold down the mouse button, as shown in the first example in Figure 18.28.

The other eyedroppers work as they do in the Levels dialog box, mapping pixels to black, medium gray, or white (or other colors if you double-click the eyedropper icons, which opens the Color Picker). For example, the White Point Eyedropper tool changes to white whichever pixel you click.

Note

Bear in mind that Photoshop maps the value to each color channel independently. So when editing a full-color image in the Curves dialog box, you need to switch channels to see the results of clicking with the eyedropper. You can further adjust the brightness value of that pixel by dragging the corresponding point in the graph, as demonstrated in the last example of the figure.

Tip

Remember to keep an eye on the Histogram palette to view dynamic, constantly updating results while working in the Curves dialog box.

Figure 18.28. Use the standard eyedropper cursor (the first of the three buttons) to locate a color in the brightness graph. Click with one of the Eyedropper tools from the Curves dialog box to map the color of that pixel in the graph. You then can edit the location of the point in the graph by dragging it.

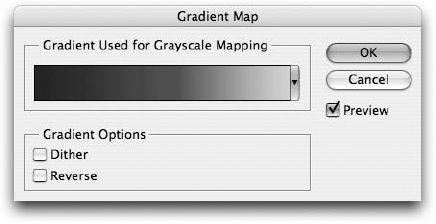

The Gradient Map command permits you to apply a gradation as a Curves map. In other words, you can use a gradient map to adjust the brightness values of an image so that they match the values in a custom gradient. Just choose Image

How does this work? Well, any gradient can be expressed as a Curves graph, progressing through a variety of brightness values in each of the three (RGB) or four (CMYK) color channels. When applied as a gradient map, the beginning of the gradient maps black and the end of the gradient maps white. If you apply the Violet, Orange preset, for example, the dark colors in the image map to violet and the light colors map to orange. Noise-type gradients (introduced in Chapter 6) produce especially interesting effects.

When drawing arbitrary curves, you may find the Pencil tool to be more flexible than the Point tool — although you will probably want to follow the Pencil tool with a click of the Smooth button so that any unwanted zigs, zags, or jags in the line can be ironed out in favor of smooth waves.

Sometimes it seems that the camera, be it digital or film, sees more than we do with our eyes. This is normally an observation made when a photo exposes some detail that no one noticed had the scene in question not been captured in a still photo, where every little object could be studied. In truth, the lens on any camera, but especially a digital camera, can't hold a candle to the human eye in terms of capturing light and color.

Modern cameras try their best to keep up with complicated and varied lighting situations, but unlike your eyes, which can probably adjust and absorb the next scene after just one blink, when it comes to a camera, you're often stuck having to choose between sacrificing the darker areas of an image or overexposing the lighter areas because the camera just can't keep up. For example, how many times have you photographed someone against the sky, only to find the sky perfectly exposed and your subject so dark you can barely make out his or her features?

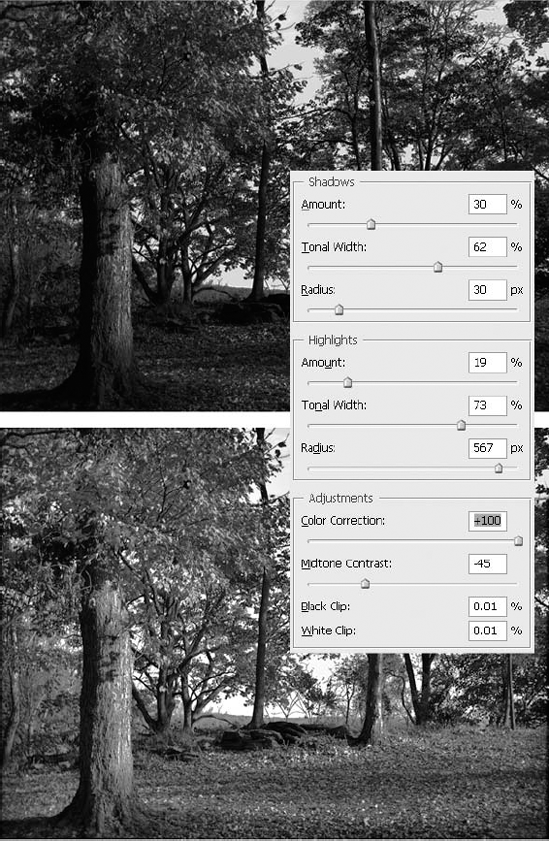

Thanks to Photoshop's Shadow/Highlight command, the camera's limitations can be accommodated. It's a great tool for both the too-bright and the too-dark photo (or portions thereof), pulling detail out of the shadows and shielding your eyes from blinding highlights. You may find that that you're happier with its results on images with dark shadows, however, but you'll be glad to have it in your arsenal for a variety of lighting problems.

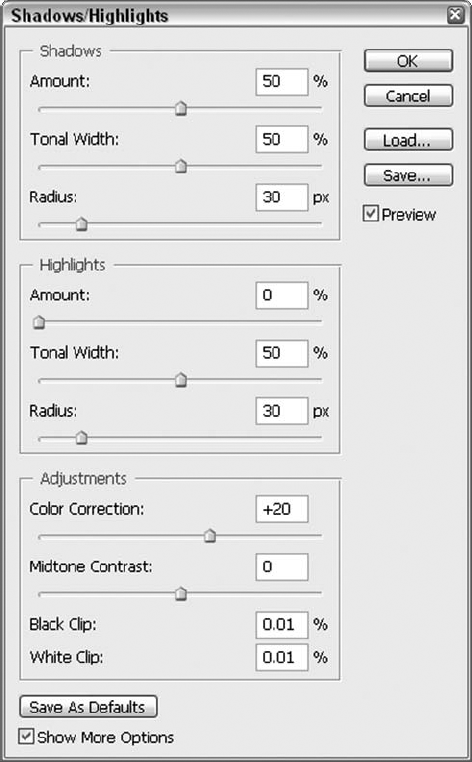

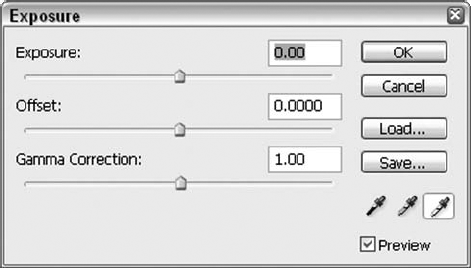

To use the command, choose Image

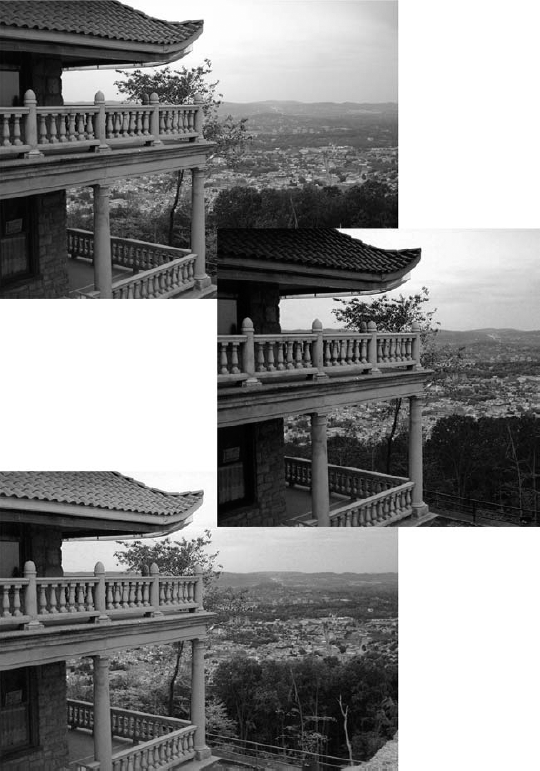

The Shadow/Highlight command examines the image and, according to your settings, deems certain spots to be "shadows" and others "highlights." From there, you adjust the sliders to tell Photoshop just how much brightening or darkening it should perform on those areas. It's a smart feature that's deceptively easy to master. The first two sections of the dialog box, Shadows and Highlights, contain identically named sliders. Naturally, the Shadows section controls the lightening of shadows in an image, and the Highlights section controls the darkening of brighter areas. Here's a list of the options available in both sections:

Amount: In the Shadows section, the Amount slider lets you specify the degree to which the shadows in an image will be lightened. In the Highlights section, the slider controls how much the highlights will be darkened. A value of 0 percent yields no change in the image; a value of 100 percent results in maximum lightening of the shadows (in the Shadows section) or darkening of the highlights (in the Highlights section). The default Shadows Amount setting of 50 percent is a safe place to start when lightening shadows in an image.