CHAPTER 2

Bodies of Knowledge and Competency Standards in Project Management

The original version of this chapter, published in the first edition of this handbook, was written when the only knowledge standard for project management was the 1987 Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®)1 developed by the Project Management Institute (PMI), headquartered in the United States. After publication of the first edition, the PMBOK® was completely rewritten and renamed A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) in 1996,2 with revised editions published in 2000, 2004, and 20083 and again in 2013,4 with the basic 1996 structure largely unchanged. In the meantime, other bodies of knowledge of project management have been developed around the world, notably in the United Kingdom, other countries in Europe, and Japan. These are all markedly different from the PMBOK® Guide, but are the de facto project management knowledge guides in their respective geographic domains. All of these bodies of knowledge are often also referred to as project management standards, and although ISO 21500:20125 provides an international standard for guidance on project management, there is still no single universally accepted body of knowledge for project management.

Concurrent with these developments, some countries and some professional associations have adopted performance-based competency standards, rather than knowledge standards, as a basis for assessing and credentialing.

Proliferation of bodies of knowledge and standards, and, more significantly, associated qualifications, are problematic for practitioners who may be forced to pursue numerous qualifications to maintain employment in the field. Attempts to develop a global body of project management knowledge have led to acceptance that different models with different underpinning philosophies will continue to coexist. Meanwhile, processes for transferability and mutual recognition of qualifications, based on comparison of bodies of knowledge and competency standards would address the practitioner’s dilemma.

This challenge is being addressed by the Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards (GAPPS), which has developed the framework entitled Global Performance Based Standards for Project Management Personnel. This global initiative is discussed further below, but first we examine the origins and natures of key bodies of knowledge and competency standards for project management.

WHY A BODY OF KNOWLEDGE FOR PROJECT MANAGEMENT?

Knowledge standards or guides, which typically take the form of bodies of knowledge, focus primarily on what project management practitioners need to know to perform effectively.

The most compelling argument for having a body of knowledge for project management is to help overcome the “reinventing-the-wheel” problem. A good body of knowledge should help practitioners do their jobs better, by both direct referencing and by use in more formal educational processes.

Koontz and O’Donnell express the need as follows: “[U]nless practitioners are to learn by trial and error (and it has been said that managers’ errors are their subordinates’ trials), there is no other place they can turn for meaningful guidance than the accumulated knowledge underlying their practice. . . .”6

Accumulated and relevant knowledge in disciplines such as engineering, architecture, accounting, and medicine is introduced to practitioners through academic degree programs that are essential prerequisites to enable them legally to practice their profession. Project management is interdisciplinary. There are no mandatory certifications limiting those who can practice project management, and the majority of practitioners hold qualifications in other disciplines, most commonly in engineering. Defining the knowledge that is specific to project management practice therefore has been an important aspect of aspiring professional formation.

Beginning in 1981, PMI took formal steps to accumulate and codify relevant knowledge by initiating the development of what became their Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®). The perceived need to do so arose from PMI’s long-term commitment to the professionalization of project management.

The initial overambitious goal of trying to codify an entire body of knowledge—surely a dynamic and changeable thing—was tempered in 1996 by the change in title to A Guide to . . . and the statement that the PMBOK® Guide was in fact, “a subset of the . . . Body of Knowledge that is generally accepted as good practice.”2 That is to say, the PMBOK® Guide is designed to define a recommended subset rather than to describe the entire field.

In summary, PMI sees its subset of the body of knowledge, as set forth in the PMBOK® Guide, as a basis for the professionalization of project management. A further purpose is provision of a guide to practitioners and a basis for assessment and certification of project management practitioners. These purposes are shared by European and Japanese professional associations in developing their own bodies of knowledge.

Initial interest in project management focused on individual projects and their managers. Since 2000, there has been increasing interest in programs and portfolios of projects and the knowledge and competencies required for their management that are different from or extend beyond the individual project. This has led to a broadening of the scope of project management standards and in some cases to the development of specific and separate standards for the management of programs and portfolios. As stated in the sixth edition of the Association of Project Management (United Kingdom), “. . . the term ‘project management body of knowledge’ no longer does justice to the broader reaches of the profession” and the use of the term P3 management has become popular in referring to management of projects, programs, and portfolios.7

We now look at some of the principal bodies of knowledge of project management, encompassing management of projects, programs, and portfolios, in more detail.

PMI’s PMBOK® Guide

PMI has produced the oldest and most widely used body of knowledge of project management, which has been modified substantially over the years. In the words of an editor of the Project Management Journal: “It was never intended that the body of knowledge could remain static. Indeed, if we have a dynamic and growing profession, then we must also have a dynamic and growing body of knowledge.”8 For this reason, bodies of knowledge and standards are subject to regular review.

The precursor of the PMBOK® was PMI’s ESA (Ethics, Standards, and Accreditation) report of 1983,9 which nominated six primary components, namely the management of scope, cost, time, quality, human resources, and communications.

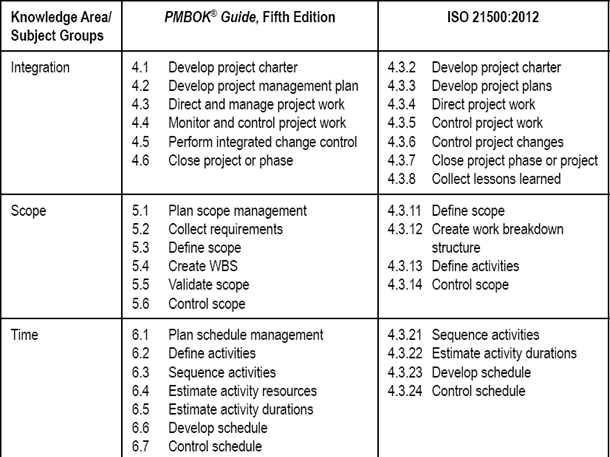

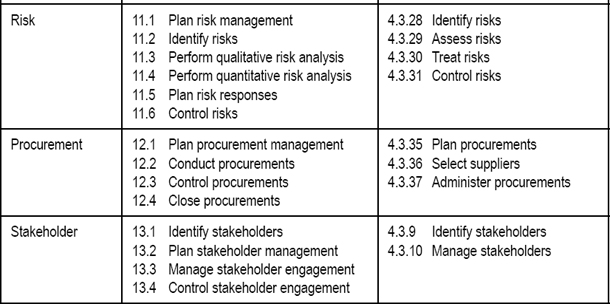

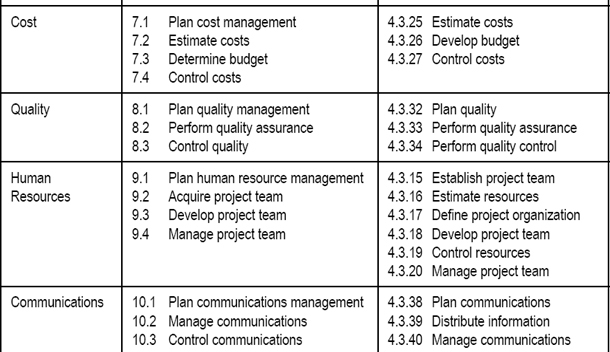

The 1987 PMBOK®1 was an entirely new document, and the first separately published body of knowledge of project management. It added contract/procurement management and risk management to the previous six primary components. The 1996 PMBOK® Guide2 was a completely rewritten document, which added project integration management to the existing eight primary components. The nine components were then renamed project management knowledge areas, with a separate chapter for each. Each knowledge area has a number of component processes, each discussed in terms of inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs. These component processes are also categorized into five project management process groups: initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing. The knowledge areas and their component processes are listed in Table 2-1.

The forty-two component processes identified in the fourth edition of the Guide were increased to forty-seven in the fifth edition. The most noticeable change was the separation of stakeholder management processes from communications management to create a new, tenth knowledge area, project stakeholder management, taking the number of knowledge areas from nine to ten.

The ten chapters in the fifth edition of the PMBOK® Guide that address the knowledge areas and component processes are preceded by one chapter dealing with the organizational context of projects and their life cycles and phases, and another chapter primarily concerned with the project management process groups. The relationship of project management with program, portfolio, and organizational project management is addressed in an introductory chapter, making it clear that these are outside the scope of the PMBOK® Guide and the subject of specific, separate PMI standards.

WBS, work breakdown structure.

Source: This table is based on information found in the fifth edition of the PMBOK® Guide, PMI, 2013.

TABLE 2-1. COMPARISON OF KNOWLEDGE AREAS/SUBJECT GROUPS IN FIFTH EDITION OF THE

In 1998, PMI was accredited as a standards developer by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and from the second edition of the PMBOK® Guide onward only the section of the guide dealing with project management processes has been identified as the standard. In the fifth edition this was clarified by including the standard for project management of a project as an annex to the Guide.

The aim of the PMBOK® Guide is to identify and describe ”that subset of the Project Management Body of Knowledge that is generally recognized as good practice” [author’s italics], and they go on to explain that “ ‘generally recognized’ means the knowledge and practices . . . applicable to most projects most of the time” and

“good practice” means there is general agreement that the application of these skills, tools, and techniques can enhance the chances of success over many projects. “Good practice” does not mean that the knowledge described should always be applied uniformly on all projects; the organization and/or project management team is responsible for determining what is appropriate for any given project.10

In summary, the PMBOK® Guide has focused on (project) management knowledge and processes that are generally recognized as good practice in the context of individual projects and has not included knowledge areas and component processes that may be relevant only on some projects or only on some occasions.

PMI has produced separate documents that it refers to as standards rather than knowledge guides, which specifically address the management of programs and portfolios. These are the standard for program management and the standard for portfolio management, both initially released in 2006. Their third editions were published in 2013.

The Association of Project Management Body of Knowledge (APMBOK®)

Morris notes that when the United Kingdom’s Association of Project Management (APM) launched its certification program in the early 1990s, it was because the APM felt that PMI’s PMBOK® did not adequately reflect the knowledge base that project management professionals need. It therefore developed its own body of knowledge, which differs markedly from PMI’s.11

The fifth edition (2006) of APMBOK®12 was organized into seven main sections, with a total of fifty-three component items. In the document there are brief discussions of all headings and topics, and references given for each topic. Morris discusses the reasons why APM did not use the PMBOK® model. In essence, he says that the different models reflect different views of the project management discipline. He notes that while the PMI model is focused on the generic processes required to accomplish a project “on time, in budget, and to scope,” APM’s reflects a wider view of the discipline, “addressing both the context of project management and the technological, commercial, and general management issues, which it believes are important to successfully accomplishing projects.”11

Morris goes on to say

. . . all the research evidence . . . shows that in order to deliver successful projects, managing scope, time, cost, resources, quality, risk, procurement, and so forth . . . alone are not enough. Just as important—sometimes more important—are issues of technology and design management, environment and external issues, people matters, business and commercial issues, and so on. Further, the research shows that defining the project is absolutely central to achieving project success. The job of managing the project begins early in the project, at the time the project definition is beginning to be explored and developed, not just after the scope, schedule, budget, and other factors have been defined. . . . APM looked for a structure that gave more recognition to these matters.11

One of the key differences between the PMI and APM approaches is that the PMBOK® Guide’s knowledge areas have focused on project management skills that are generally recognized as good practice, whereas contextual issues and the like are discussed separately in its Framework section. On the other hand, the APMBOK® includes knowledge and practices that may apply to some projects or part of the time, which is a much more inclusive approach. This is exampled by the fact that the PMBOK® Guide specifically excludes safety, while the APMBOK® specifically includes safety.

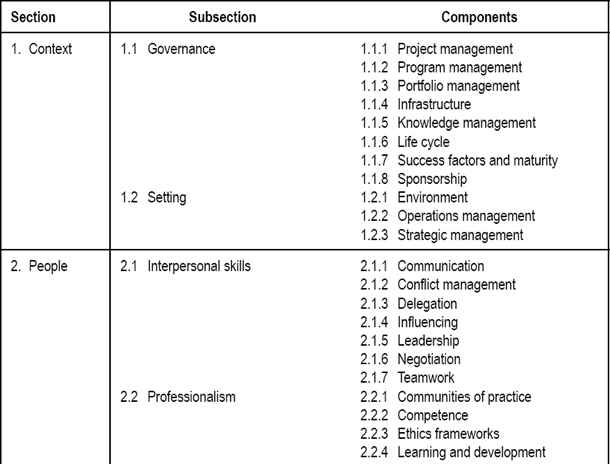

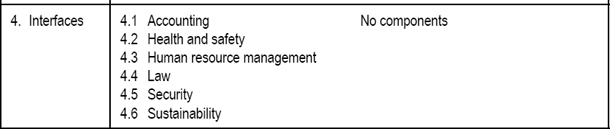

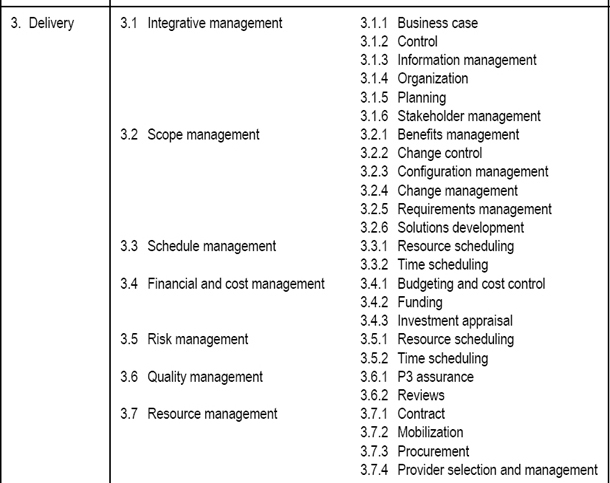

The sixth edition of the APMBOK®, released in 2012,7 retained the inclusive philosophy of previous versions but changed significantly in terms of structure and delivery. The structure was reduced from seven sections with fifty-three components, to four main sections covering context, people, delivery and interfaces, fifteen subsections, and fifty-three components. The section on delivery equates most directly to the PMBOK® Guide, but the approach and content are noticeably different. The PMBOK® Guide knowledge areas are presented in considerable detail, more or less in the form that might be expected in a textbook, and, as noted previously, relate only to projects. The APMBOK® is much broader in scope, covering projects, programs, and portfolios, in the form of an overview, providing references for further reading. In part because the scope is broader, topic coverage is more expansive, including benefits management, which is not mentioned in the PMBOK® Guide. In terms of delivery modes, although it is still available in traditional book form, both hardcover and paperback, the APMBOK® is also provided online in interactive format. This enables users to search it, to access material that is either generic or specific to management at the level of project, programs or portfolios, and to provide real-time feedback and suggestions for review. Table 2-2 displays the structure of the APMBOK®, Sixth Edition.

International Project Management Association Competency Baseline (ICB)

Following the publication and translation of the first editions of the APMBOK® in 1992 and 1994, several European countries, including Austria, France, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, developed their own bodies of knowledge.

Drawing on these bodies of knowledge, the International Project Management Association (IPMA), a federation of national project management associations, mainly European, developed an IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB) in the late 1990s. This was reviewed and updated in 1999 (Version 2) and again in 2006 (Version 3.0). The primary purpose of the ICB is to provide a reference basis for its member associations to develop their own national competence baselines (NCBs). Another purpose of the ICB was to “harmonize” the then-existing European bodies of knowledge, particularly those of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Switzerland. The majority of members have since developed their own baselines, which may include additional elements to reflect any cultural differences and provide a basis for certification of their project managers.13

In spite of its name, the majority of the content of the ICB Version 3.0 can be seen primarily as a knowledge guide, although it is explicitly intended as a basis for assessment and certification at four levels—IPMA A, B, C, and D. Competence in the ICB is defined as a “collection of knowledge, personal attitudes, skills and relevant experience needed to be successful in a certain function.”

The ICB comprises some forty-six competence elements of which twenty are classified as technical, fifteen as behavioral, and eleven as contextual. The forty-six competence elements are required to be included in each member’s national competence baseline (NCB). Like the APMBOK®, the ICB is inclusive in that it considers not only the project, but also the program and portfolio.

Japan’s P2M

In mid-1999, Japan’s Engineering Advancement Association (ENAA) received a commission from the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry to establish a new Japanese-type project management knowledge system and a qualification system. ENAA established a committee for the introduction, development, and research on project management, which produced A Guidebook of Project and Program Management for Enterprise Innovation (officially abbreviated as P2M) in 2001, with English revisions in 2002, 2004, and 2008.14 The Japanese approach was from the start both broad and inclusive.

TABLE 2-2. CONTENT AND STRUCTURE OF APM BODY OF KNOWLEDGE (SIXTH EDITION)

The task of issuing, maintaining, and upgrading P2M was undertaken by the Project Management Professionals Certification Center (PMCC) of Japan (formed in 2002), which also implemented a certification system for project professionals in Japan, based on P2M. The PMCC consolidated its organization with that of the Japan Project Management Forum [(JPMF), which was originally inaugurated in 1998] in November 2005, to make a fresh start as the Project Management Association of Japan (PMAJ), which is the publisher of the 2008 edition of P2M.

The rationale for developing P2M and the certification system was a perceived need for Japanese enterprises to institute more innovative approaches to developing their businesses, particularly in the context of the increasingly competitive global business environment, and also a perceived need to provide improved public services. The key concept in addressing this need is “value creation.” The recommended means of achieving value creation is through developing an enterprise mission, then strategies to accomplish this mission, followed by planned programs to implement these strategies, and then specific projects to achieve each of the programs. The focus of P2M is on how to facilitate the effective planning, management, and implementation of such programs and projects.

The original Japanese document comprises 420 pages, so it is a large and very detailed document. The P2M not only covers the management of single projects, but also has a major section specifically on program management. It has chapters on the following topics, under the overall heading of Domain Management, applicable to projects and programs:

1. Project Strategy Management

2. Project Finance Management

3. Project Systems Management

4. Project Organization Management

5. Project Objectives Management

6. Project Resources Management

7. Risk Management

8. Program and Project Information Management

9. Project Relationships Management

11. Project Communications Management

TOWARD A GLOBAL BODY OF KNOWLEDGE

No single, globally accepted, body of knowledge of project management currently exists. Each major professional association has a vested interest in maintaining its own body of knowledge, as each case has entailed a considerable investment in, and commitment to, subsequent certification processes. It is, therefore, difficult to envisage any situation that might prompt professional associations to voluntarily cooperate to develop a global body of knowledge to which they would commit themselves. Representatives of thirty-one countries and a wide range of project management professional associations were brought together by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) to develop ISO 21500:2012 Guidance on Project Management, but it is not intended as a body of knowledge or basis for education and certification. It may influence the content of the various bodies of knowledge, but there is no indication that it is likely to replace them.

Nonetheless, since the mid-1990s, discussions at global forums, often in association with major project management conferences, indicated that there is a wide recognition that a globally recognized body of knowledge would be highly desirable.

One particular initiative was the coming together of a small group of internationally recognized experts to initiate workshops, beginning in 1998, to develop a global body of project management knowledge. This group, known as the OLCI (Operational Level Coordination Initiative) recognized that one single document cannot realistically capture the entire body of project management knowledge, particularly emerging practices, such as in managing “soft” projects (e.g., organizational change projects), cutting-edge research work, unpublished materials, and implicit as well as explicit knowledge and practice. Rather, there has emerged a shared recognition that the various guides and standards represent different and enriching views of selected aspects of the same overall body of knowledge.15

COMPETENCY STANDARDS

Competency has been defined as “the ability to perform the activities within an occupation or function to the standard expected in employment.”16 There are two primary approaches to inferring competency: attribute based and performance based.

The attribute-based approach involves definition of a series of personal attributes (e.g., a set of skills, knowledge, and attitudes) that are believed to underlie competence, and then testing whether those attributes are present at an appropriate level in the individual.

The performance-based approach is to observe the performance of individuals in the actual workplace, from which underlying competence can be inferred. This has been the approach adopted by the Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM) as a basis for its certification/registration program.

Several factors combined to lead AIPM to adopt the competency standards approach. First, there was recognition that the possession of knowledge about a subject does not necessarily mean competence in applying that knowledge in practice. More significantly, however, in the early 1990s when the AIPM was developing its certification program for project managers, the Australian government, through its Department of Employment, Education, and Training (DEET) and National Office of Overseas Skills Recognition (NOOSR), was very actively promoting the development of national competency standards for the professions.

With support of the Australian government the AIPM led the development of the first Australian National Competency Standards for Project Management (NCSPM), which were released in 1996 in the context of the Australian Qualifications Framework. A conscious decision was made to align the NCSPM units of competency with the nine knowledge areas of the PMBOK® Guide, which was released in the same year. For well over a decade the Australian national standards provided the basis for AIPM’s professional registration program.17

The format of Australian Competency Standards, which is similar to frameworks developed by the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and South African governments, emphasizes performance-oriented recognition of competence in the workplace, and includes the following main components:

• Units of competency: the significant major functions of the profession

• Elements of competency: the building blocks of each unit of competency

• Performance criteria: the type of performance in the workplace that would constitute adequate evidence of personal competence

• Range indicators: the precise circumstances in which the performance criteria would be applied

The elements of competency are expressed in action words, such as determine, guide, conduct, implement, assess outcomes, and the like. There are generally three elements of competency for each unit, but occasionally more. There are typically two to four performance criteria for each element of competency.

In 2008 the AIPM released its own Professional Competency Standards for Project Management, so that its registration program was no longer directly aligned with the Australian Qualifications Framework. In keeping with the competency standards approach, standards are written for specific roles. The AIPM has standards for roles of project practitioner, project manager and project director for which the units of competence remain closely aligned to the knowledge areas of the PMBOK® Guide. More recently released standards for the role of project portfolio executive have a different focus that reflects the broadening context of project management.

The units of the 2013 version of the government-endorsed Australian National Competency Standards for Project Management remain focused on the project and continue to reflect the knowledge areas of the PMBOK® Guide. They are presented in the form of qualifications that are generally applicable to roles of project team members, project managers, and project directors.18

Other Competency Standards

Both the United Kingdom and South Africa have performance-based competency standards for project management that form part of the national qualifications frameworks. The Occupational Standards Council for Engineering first produced standards for project controls (1996) and for project management (1997). These are maintained and reviewed by the Engineering Construction Industry Training Board (ECITB). These United Kingdom and South African standards are formally recognized and provide the basis for award of qualifications within their respective national qualifications frameworks.19

PMI has produced a Project Manager Competency Development Framework that is not considered a standard but is intended as a resource for practitioner development.20 In the United Kingdom, the Association for Project Management published the APM Competence Framework in 2008. This is linked to the APMBOK® (Fifth Edition) and the ICB-IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0.21

Toward Global Performance-Based Competency Standards

A global effort for the development of a framework of Global Performance-Based Standards for Project Management Personnel (now known as the Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards [GAPPS]) was initiated in 2003, with preparatory work going back to the late 1990s. The work of an international group, with representatives from major international project management associations, industry, and academia, the intent of this endeavor is to provide a basis for comparison of standards and mutual recognition of qualifications.22

The GAPPS has two main streams of activity: the development of performance based standards for project management in its broadest sense, and the mapping or comparison of project management standards and qualifications. The primary purpose of the development of standards is to provide a neutral core against which the content of other standards can be mapped, but in some cases, notably the role of project sponsor, standards are developed in response to demand where no other standards currently exist. The process for development of performance-based standards has been well developed since the late 1980s by governments in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. The GAPPS draws upon this depth of experience, following established standards development practices and drawing upon existing standards, the input of practitioners, and relevant research.

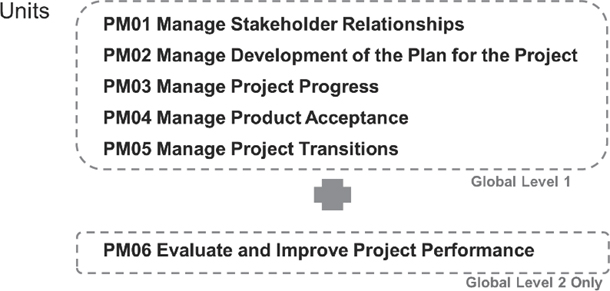

The GAPPS Project Manager Standard was first released in 2006. A table for evaluating the management complexity of project roles, the Crawford-Ishikura Factor Table for Evaluating Roles (CIFTER), was developed and has been adopted by a number of global organizations as a basis for categorization of projects and determining the level of competence required to manage them. Based on this categorization, two levels of project manager standards, global level 1 and global level 2, are identified. The GAPPS project manager standard focuses on the project but does not adopt the knowledge or functional area structure followed by the majority of other project management standards taking a more integrated and practice-based approach. There are only five units of competence required at global level 1 and six units at global level 2, as illustrated in Figure 2-1.23

FIGURE 2-1. UNITS OF COMPETENCY—GAPPS PROJECT MANAGER STANDARD

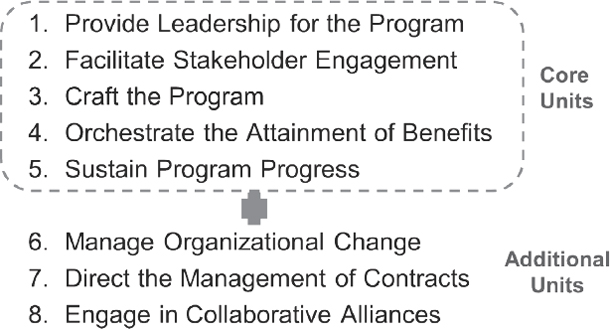

In 2011 a Program Manager Standard was released. This standard has five core units of competence, applicable to all program managers and three additional units applicable only in some contexts (see Figure 2-2).24

Combinations of these core and additional units produce six different categories of program manager role. A tool for assessing program management complexity, the Aitken-Carnegie-Duncan Complexity (ACDC) Table, is provided as a basis for differentiating levels of program manager role.

In addition to providing a basis for mapping and comparison of content, these GAPPS standards are being used and adapted by organizations often in association with the knowledge-based standards of the various professional associations as a basis for determining competence, based on evidence of workplace application.

All work of the GAPPS is undertaken by volunteers, and the output is made freely available via the GAPPS website (www.globalpmstandards.org), which offers a valuable and continually updated resource providing guidance on the comparability of project management bodies of knowledge, standards, and assessment processes.

FIGURE 2-2. UNITS OF COMPETENCY—GAPPS PROGRAM MANAGER STANDARD

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

![]() In your own career, what aspects of general management are equally important to project management skills and knowledge? Should project management perhaps be considered a “general management” skill?

In your own career, what aspects of general management are equally important to project management skills and knowledge? Should project management perhaps be considered a “general management” skill?

![]() There are many competing bodies of knowledge and competency standards for project management. Do you consider this an advantage or disadvantage for practice and for the development of a profession of project management?

There are many competing bodies of knowledge and competency standards for project management. Do you consider this an advantage or disadvantage for practice and for the development of a profession of project management?

![]() Discuss the difference between attribute-based and performance-based competency models. If your competency were required to be measured, which would you prefer to be gauged by?

Discuss the difference between attribute-based and performance-based competency models. If your competency were required to be measured, which would you prefer to be gauged by?

REFERENCES

1 Project Management Institute, Project Management Body of Knowledge (Drexel Hill, PA: PMI, 1987).

2 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, (PMBOK® Guide) (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 1996).

3 A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 4th edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2008), p. 4.

4 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2013).

5 International Organization for Standardization, ISO 21500:2012 Guidance on Project Management (Geneva, Switzerland: ISO, 2012).

6 H. Koontz and C. O’Donnell, Essentials of Management (New Delhi, India: Tata McGraw-Hill, 1978).

7 Association for Project Management, APM Body of Knowledge, 6th edition (Princes Risborough, UK: APM, 2012).

8 Project Management Institute, “Project management body of knowledge: special summer issue,” Project Management Journal 17, No. 3 (1986), p. 15.

9 Project Management Institute, “Ethics, standards, accreditation: special report,” Project Management Quarterly. PMI: Newtown Square, PA. August, 1983.

10 PMI, 2008, p. 4.

11 Peter W.G. Morris, “Updating the project management bodies of knowledge,” Project Management Journal 32 (2001), p. 22.

12 Association for Project Management, APM Body of Knowledge, 5th edition (High Wycombe: UK, 2006).

13 International Project Management Association, ICB: IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0. (Nijkerk, The Netherlands: IPMA, 2006).

14 Project Management Association of Japan, P2M: Project and Program Management for Enterprise Innovation: Guidebook (Tokyo, Japan: PMAJ, 2008).

15 Lynn Crawford, “Global body of project management knowledge and standards,” in P.W.G. Morris and J.K. Pinto (editors), The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects, Chapter 46. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

16 L. Heywood, A. Gonczi, and P. Hager, A Guide to Development of Competency Standards for Professions: Research Paper 7, (Australia: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1992).

17 Australian Institute of Project Management (Sponsor), National Competency Standards for Project Management. (Sydney, Australia: AIPM, 1996). Standard can be viewed at www.aipm.com.au.

18 Innovation and Business Skills Australia BSB07—Business Services Training Package: Release 8.1. (East Melbourne, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia, 2013).

19 Engineering Construction Industry Training Board, National Occupation Standards for Project Management (Kings Langley, UK: ECITB, 2002).

20 Project Management Institute, Project Manager Competency Development Framework (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2007).

21 Association for Project Management, APM Competence Framework (Princes Risborough, UK: APM, 2008).

22 Lynn Crawford and J.B. Pollack, “Developing a basis for global reciprocity: negotiating between the many standards for project management,” International Journal of IT Standards and Standardization Research 6 (2008), pp. 70–84.

23 Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards, A Framework for Performance Based Competency Standards for Global Level 1 and 2 Project Managers (Johannesburg, South Africa: GAPPS, 2006, with technical revision, 2007).

24 Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards, A Framework for Performance Based Competency Standards for Program Managers (Sydney, Australia: GAPPS, 2011). Accessible online at www.globalpmstandards.org.