CHAPTER 42

Sustainability and Project Management

To appreciate and understand the practice of sustainable project management, the project manager should have a fundamental understanding of the drivers of what we refer to as the “green wave”—the growing awareness by individuals of the need for sustainability and the practices that support it. Project managers should have this understanding in their quivers, because knowledge of the drivers and influencers can help to better understand stakeholders’ expectations. More and more organizations have sustainability goals, objectives, and intentions within their mission/vision statements, and they are very serious about achieving them. Connecting your project management efforts with those sustainability efforts of the organization is necessary for project success.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Nothing sparks more debate than the mention of global climate change (GCC). Whenever GCC is brought up, it is usually in conjunction with greenhouse gas (GHG) buildup in the atmosphere. The primary contributor to GHGs is carbon dioxide (CO2), a by-product of fossil fuel combustion. Whether or not you believe GHG buildup is exacerbated by humankind (and there is an abundance of evidence that says it is),1 more and more stakeholders are caring about it. Project managers have always cared about stakeholder perception, and the Project Management Institute’s Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), fifth edition, reinforces the need to consider stakeholders, as it devotes a full new knowledge area to this topic. Even when stakeholders are not conversant with the risks and impacts of GCC, it behooves the project manager to consider the risks and uncertainties exacerbated by it, as well as the economic changes it is generating. Companies that were engaged in development along the shore in New Jersey and New York, for example, would perhaps have benefited from having project managers who were aware of the heightened risk when Hurricane Sandy struck in 2012.2

THE TRIPLE (AND MORE) BOTTOM LINE

Holistic thinking entails working as if everything is connected, because it is. To quote the memorable character Hushpuppy from Beasts of the Southern Wild (directed by Benh Zeitlin; Journeyman Pictures, 2012): “The whole universe depends on everything fitting together just right. If one piece busts, even the smallest piece . . . the entire universe will get busted” (screenplay by Lucy Alibar and Benh Zeitlin). Stated a bit more formally, we are coming to realize that the environment and the economy are connected; often an economic gain that comes at the expense of the environment proves to be a cost in the long run. Planning ahead to mitigate environmental and social impacts, instead of doing what is cheap and expedient and hoping not to be sued, is a core concept for sustainable business activities.

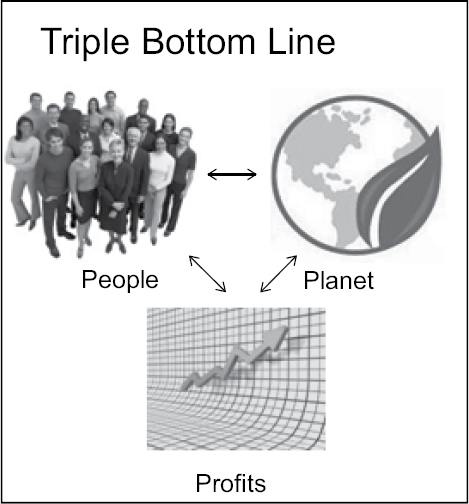

As a framework for thinking holistically about business activities, the triple bottom line (TBL) (Figure 42-1), which considers the social and political (people), environmental/ecological (planet), and financial (profits) aspects of a business, has been widely accepted since its introduction in 1994. It aims to measure the social, environmental, and financial performance of a company or project. The key thought behind this model is that only by figuring in all three aspects of business can an organization estimate the full cost involved in doing business. According to The Economist, “In some senses the TBL is a particular manifestation of the balanced scorecard. Behind it lies the same fundamental principle: what you measure is what you get, because what you measure is what you are likely to pay attention to. Only when companies measure their social and environmental impact will we have socially and environmentally responsible organizations.”3

FIGURE 42-1. THE TRIPLE BOTTOM LINE

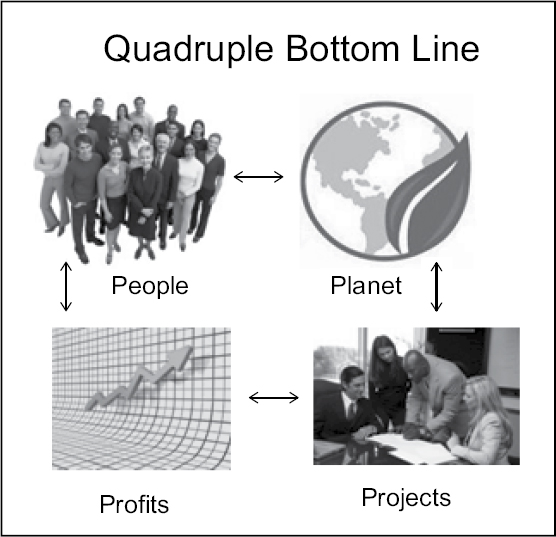

FIGURE 42-2. THE QUADRUPLE BOTTOM LINE

We have added projects to the mix to propose a quadruple bottom line (Figure 42-2). Because projects are responsible for economic activities that use resources and create change—from construction projects to new manufacturing facilities to process improvements and more—project managers have the opportunity and responsibility to be on the leading edge of incorporating sustainable practices. Almost any project can benefit in either cost reduction, morale improvement, stakeholder satisfaction, or reduction of total cost of ownership from a project manager who “thinks green.”

STANDARDS AND REGULATIONS

The quadruple bottom line is not the only consideration for the project manager to be more sustainable. There is also another “P”: politics. Although potentially connected to profits, there are both mandates and guidelines that can affect the organizations decision to be more sustainable. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the European Environmental Agency (EEA) both have enacted legislation to protect the environment. State and individual country regulations must also be considered. In fact, in a major speech on climate change, President Barack Obama has added significant new restrictions on new and existing power plants with respect to carbon emissions.4 Lack of consideration of these regulatory issues can affect both the reputation of an organization as well as the bottom line. In addition, the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 14000 is a group of standards that apply to the sustainability of an organization. For example, ISO 14001 specifies requirements for an environmental management system; ISO 14010/11 provides general principle for environmental auditing reviews. To be considered ISO 14000–compliant is similar to the prestige associated with complying with ISO 9000 manufacturing standards. ISO 14000 provides another tool for the project manager to use to consider an organization’s sustainability.5

Adherence to standards and regulations can boost an organization’s reputation and keep it out of trouble with regulators, but a major influence on sustainability is the “bottom-up” demand from stakeholders. Stakeholder influence on the success of a project is becoming greater and greater. Stakeholders are becoming more and more aware of environmental issue drivers and indicators. They are bombarded by advertisements about green products and services, and they are making greener choices. In addition, major retailers like Walmart are using greener vendors to take advantage of customer (stakeholder) perceptions.6

GREENALITY

During the writing of our book, Green Project Management, we searched for a word that would capture the essence of what we and others in the field were trying to express. Authors were struggling with words like “greenness” and “environmentally friendly,” but none seemed to satisfy our exact intent, which was for project management to make sustainability one of the standard factors considered in planning and risk management. The word we coined is greenality, which we define as the consideration of all green factors that affect a project during the project life cycle. It includes two project management processes:

1. Plan to minimize the environmental impacts of a projects.

2. Monitor and control the environmental impacts of a project and its product.

Greenality is “green” and “quality” smashed together. Taking the attributes of quality—conformance to requirements, planning (not relying on inspection for quality), not accepting “that’s good enough,” and following quality throughout all the processes (e.g., procurement), reducing project waste—we apply them to sustainability. Attributes for the word green would be applying the sustainability intent of the organization’s mission/vision, planning for sustainability within the project plan, reducing project waste, checking the supply chain for sustainability, constantly improving sustainability efforts, thereby improving sustainability of the organization and considering the entire life cycle of the project’s outcome.

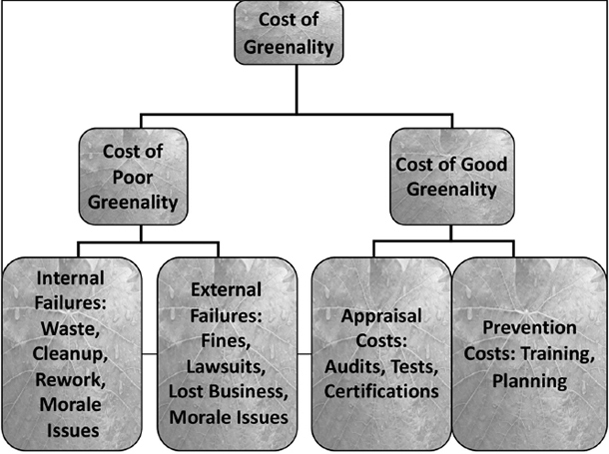

Cost of Greenality

Further, just like quality, greenality has its cost. There is a cost to good greenality and a cost to bad greenality. Figure 42-3 is our interpretation of the cost of greenality. We’ve all seen a similar chart to this about quality.

Using the example of the so-called Deepwater Horizon/BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill (this was actually BP’s Macondo well) in 2010, in our interpretation, the cost of poor greenality far outweighed the cost of good greenality. (Disclaimer: we were not in the room when these decisions were made, so we do not have all of the facts that led to the decision, and thus this is speculation based on the best information available in the media.) While BP did conduct some testing of the well casing, we believe that a cement bond log test (a prevention cost) may have indicated some serious problems with the well casing. Whether or not that test could have prevented the disaster is unclear. But using that test as an example of the cost of greenality, a $100,000 test is always better than an estimated $50+ billion price tag for external failure, not even considering the loss of life or loss of reputation for the company. Even though the “accident” occurred three years ago, executives are still being indicted, and the long-term environmental health of the ecosystem in the Gulf remains unclear.7

FIGURE 42-3. THE COST OF GREENALITY

Reducing Non-Product Output (NPO)

This element of greenality is nothing new for the project manager. Reducing non-product output (NPO) is a way to reduce resources and thereby reduce project costs. The NPOs are the “leftovers”—what is left once all the efforts for redesign and reduction have been exhausted before reuse or recycling efforts have begun. “One example of NPO is the carbon emission of the project. Once the efforts identified in the project planning process are implemented, they are monitored via performance measurements. For instance, have the efforts been implemented so that the anticipated remediation has been realized? How does the project manager measure success of that effort?”8

The project manager can then look at the energy (a limited resource) use of the project itself. Has the project team utilized that limited resource conservatively, exploiting energy reduction tools within their PCs, turning them and all peripherals off when not in use by using power strips? Looking at the project team environment, are the lights on motion sensors, is travel minimized by using a Skype-type virtual meeting tool?

The key to reducing NPO is to first establish a baseline. Where are we right now? Once that baseline is established, the project manager can compare that to best-in-class, organization goals, or other targets to see what improvements can and should be made to reduce NPO as well as aligning those targets with organizational sustainability strategies.

BECOMING CONVERSANT IN SUSTAINABILITY

Even if this entire handbook was dedicated to the language of sustainability, it couldn’t really cover the topic. It is broad and multifaceted. However, there are a few key terms and concepts that will help the project manager be more conversant in sustainability.

The Natural Step

The Natural Step (www.naturalstep.org) is the foundational organization for sustainability. Its four system conditions and four principles of sustainability form the basis for most studies of sustainability. The four system conditions are described as follows: “In a sustainable society, nature is not subject to systematically increasing: (1) concentrations of substances in the earth’s crust, (2) concentrations of substances produced by society, (3) degradation by physical means, and (4) in that society, people are not subject to conditions that systematically undermine their capacity to meet their needs.”

These conditions are answered by the four principles of sustainability: “To become a sustainable society we must eliminate our contribution to: (1) the systematic increase of substances extracted from the Earth’s crust (for example, heavy metals and fossil fuels), (2) the systematic increase of concentrations of substances produced by society (for example, dioxins and DDT), (3) the systematic physical degradation of nature and natural processes (for example, over harvesting forests and paving over critical wildlife habitat); and (4) conditions that systematically undermine people’s capacity to meet their basic human needs (for example, unsafe working conditions and not enough pay to live on.” The Natural Step conditions and principles cover the entire spectrum from the environment through corporate social responsibility.9

Carbon

There are descriptor words associated with carbon that should be part of the project manager’s vocabulary: carbon footprint, carbon trading, and carbon offsets. Your carbon footprint is the measure of environmental impact that you have. For organizations it includes the impact the organization has on the environment and the environmental impact of the employees. There are various calculators for both personal and organization measures. A search of the Internet can provide the project manager with measurement tools. The results of those measurements will add to the baseline information. The more baseline information collected, the easier it will be to decide where the best efforts can be used to save valuable resources.

Carbon trading and carbon offsets are related. The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Kyoto Protocol is an agreement between nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As a result of the agreement, nations are required to reduce their carbon emissions. Carbon trading assigns an economic value to carbon, and then countries can buy or sell rights. The selling country gives up its rights to burn carbon, reducing its emissions, while the buying country “buys” the right to burn carbon thus “offsetting” one country’s carbon emission with another’s. This is the relationship between carbon trading and carbon offsets. This works because the goal of the Kyoto Protocol is to reduce the collective carbon emissions. Carbon trading is the process and carbon offsets are the results.

Cradle to Cradle

A buzz phrase of the past was cradle to grave. In the traditional, project management sense, that meant that project managers’ main concern was from when they took on the project to when it was turned over to operations. We assert that, by stopping at the turnover to operations, the project is not complete from a sustainability aspect. The project’s holistic view includes the consideration of the final end product throughout its life cycle. For example, what happens to a bridge when the end of its useful life is reached? During the concept phase, have we considered reuse and recycling of the building materials? Has the bridge been designed with the ultimate disposal in mind?10

THE INTERSECTION OF SUSTAINABILITY AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT

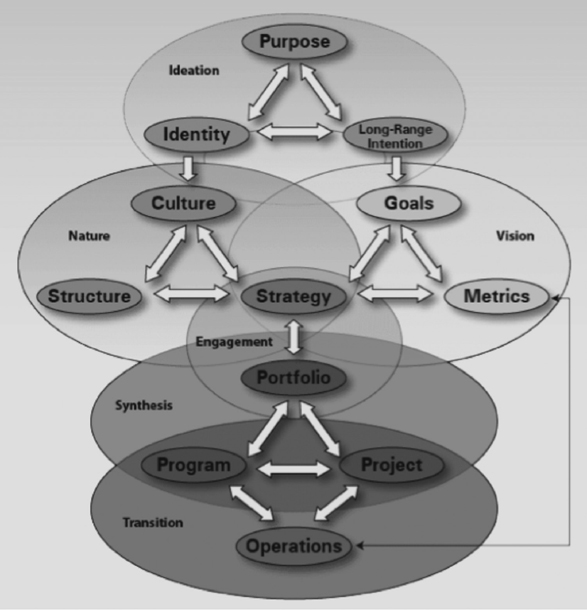

Sustainable project management is merely an extension of traditional project management (defined above as “complete at turnover to operations”). In Figure 42-4, program and project are at the intersection of portfolio and operations, with a direct link to execution of an organization’s strategy. Project management connects strategy and operations, providing the ideal facilitator for the adoption of sustainable practices. (The strategic execution framework is used as the basis of Stanford University’s Center for Professional Development’s Certificate in Advanced Project Management.) Strategy is part of the mission/vision of an organization. That mission/vision will increasingly include elements of sustainability. The connection between the organization’s mission/vision and the project’s mission/vision is critical to the success of the project. Without that connection, stakeholder expectations will not be met.

Traditionally, the project manager’s role began after the business case was complete, and finished when the project (or product of the project) was turned over to ongoing operations. Sustainable project management requires that the project manager drive backward and forward. As stated above, the project manager should be involved early in the decision process to ensure that sustainability elements of the organization’s mission/vision are included in the requirements, and forward into the process to ensure that the long-term effects of the project or product of the project are monitored and controlled.

FIGURE 42-4. STRATEGIC EXECUTION FRAMEWORK

Source: Adapted from the Stanford Execution Framework, IPS Learning, 2013, http://ipslearning.com/content/strategic-execution-framework. Used with permission.)

TAP INTO THE POWER OF YOUR ORGANIZATION

There is a great deal of potential energy in your organization’s purpose, identity, and long-range intentions (Figure 42-4). These are the top leadership ideals that are often publicly communicated to shareholders and employees. They give “ideation” to your organization.

Now let’s jump down to the bottom of Figure 42-4. Your organization’s heartbeat, its flow, is its operations. This is the day-to-day reality of your business.

And where are we, the project, program, and portfolio managers of the world? We, dear friends, are where the rubber (the strategy) meets the road (the operations).

Project managers can gain power by aligning with the organization’s strategy, but we often overlook this. In the past, we have insisted that project managers put on blinders when it comes to the “end” of their project, failing to connect with the operations of the company. Why? We’re programmed to consider a project as having a definitive beginning and end, and that end occurs when we hand over the final deliverable.

But “final” is not so final, after all. When a project, such as the bridge discussed above, is “done,” that only means that it can begin carrying vehicles over a river. Does this mean we, as project managers, have to continue monitoring each car as it goes over the bridge? Of course not. But it does mean that we should think about the long-term disposition of the bridge in the steady state. It will help us identify risk, connect with stakeholders that we might not have thought of, and in general do a better job of creating sustainable projects. In the bridge example, we assert that the project manager should consider the paving material, not just for its ability to provide improved mileage for vehicles, but also for its ability to withstand heating and cooling without breaking up and requiring repaving every year. At least ask these questions. It will help you connect to the operations below and the long-range initiatives above.

Take another look at Figure 42-4. See how important it is for an organization to plug together all of the pieces if they want to get to a sustainable steady state. And guess who is at the center of it all? You, the well-connected project, program, or portfolio manager.

The project manager can gain “sustainability power” in two ways:

1. Connect upwards: You don’t have to be a top corporate leader or CEO to know and live the organizations’ strategies. Read and reread your organization’s mission, vision, and values statements. Check messaging from company leaders. Of course we would steer you to messages on sustainability and the environment, but you can derive power for your projects’ charters from any of strategic messages communicated by the C-level.

2. Connect downwards: You can, and should, consider project management as distinct from operations. But that doesn’t mean we have to ignore them. Get to know the people who will operate the product of your project. Understand the set of users as a stakeholder group and drink in their requirements and expectations as fodder for risk identification. Think life cycle. What happens to your final product in operations and in the long term? Can you learn anything with that mindset? We assert that you absolutely can.

Plug in! Peers in both directions are working toward sustainability, both economic and ecological. We need to pair with these colleagues and learn from both. Understand how project management processes themselves can be more sustainable.

Sustainability is not a separate process or a new knowledge area for project managers. Rather, sustainability must be integrated into the overall framework of our discipline. Having said that, there are indeed specific touch points within our discipline that warrant special attention, and we’ll cover those in the next pages. But it is critical that sustainability thinking, in particular long-term, product-oriented thinking, be part of (especially) the integrating and planning processes, where it can have more of an effect on the product of the project.

Here are examples of this integrated thinking:

• Chartering the project: a broadened view of what success means for the project, in line with the organization’s overall ideation.

• Identifying stakeholders: include, for example, environmental groups (and other nongovernmental organizations [NGOs]) and your company’s environmental health and safety (EH&S) organization, as well as the operations group that will take the product of your project and use it in the steady state. Also consider your company’s public statements and commitments in the area of sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

As far as the project itself is concerned, there are opportunities to be more efficient as a project as well. This includes reduction of waste by the project team itself (literally, turning off the lights, going paperless, etc.), but it also includes more sweeping project sustainability such as following lean management principles in the creation of your project’s product.

Each time a project manager shares a best practice or lesson learned with colleagues, preventing bad decisions, poor choices of vendors or materials, and frequent rework, the project management discipline itself becomes more sustainable at your enterprise—ecologically, from a human standpoint, and from an economic perspective as well.

How else can the integration of sustainability into your project assist the project itself? Here are three examples:

1. Support from “triple bottom line” (TBL) stakeholders: Chances are, there are people in powerful positions—sponsors, perhaps—who already are thinking in terms of the triple bottom line. They can help you, if you get them interested in those aspects of your project. Of course, this could just as well be the case for some of your key customers. Walmart comes to mind as an influential customer of many suppliers, one that was able to assert their TBL thinking as a customer and significantly drive change back to their suppliers. And finally, project team members and project team contributors are also likely to be TBL thinkers. Assuring that sustainability is integrated will gain you buy-in from these like-minded team members.

2. Smoother hand-off to operations: Understanding how the product of the project will be used doesn’t just help you with sustainability; it reduces the chances of surprises when the project is handed over to an operations team—which are often bad surprises, such as a product that works well in the lab but not in the field.

3. Increased and improved risk identification, analysis, response, monitoring, and controlling: There is nothing fundamentally different about the way in which risks related to sustainability are analyzed and responded to. What is different is that we have to remove our blinders to look for a larger set of risks, by including the longer term, and by understanding a wider set of stakeholders, who, in turn, may be taking a wider view than we’d traditionally think. For example, whole new sets of risks (both threats and opportunities) may be introduced by virtue of sponsors, customers, or suppliers who are sustainability-minded. Indeed, there could be an opportunity (as Coca Cola and other large multinational companies have found) to partner with an NGO (like the World Wildlife Federation) for mutual benefit.

Examples abound in industry where sustainability risks were not properly identified at the start of the project and thus no analysis or risk response plan was created.

Take, for example, the very real case of a large multinational oil company that had zero environmental or safety risks identified in its risk register, yet had a major blowout and oil spill in an important body of water. The company had to scurry to come up with an expensive workaround plan, which did not properly treat the risk, yielding not only the (significant) workaround expenses themselves, but also billions of dollars in fines and penalties, loss of brand reputation, and still-to-be-quantified long-term damage to the ocean and shore environment.

Staying with this example for a moment, we can also consider the advantage of using sustainability thinking in identifying secondary risk. Some of the chemicals used to treat and contain an oil spill on the water have their own negative effects on the environment. Have these threats been considered when deciding to make the use of this chemical a risk response?

SUSTAINABILITY THINKING AND PROJECT QUALITY

Project managers will likely align with the concepts of quality as they pertain to sustainability for two reasons. First, much of the project quality training we receive is product related, which means it is linked to the long-term product of the project. Second, quality gurus, such as W. Edwards Deming, Joseph Juran, and Kaoru Ishikawa, were long-term, holistic thinkers. In fact, it is possible to apply each of Deming’s 14 points to “green quality.”11

LIFE-CYCLE THINKING FOR PROJECT MANAGERS

In a very interesting book, The Discovery of Heaven by Harry Mulisch, the table of contents looks like this:

1. The Beginning of the Beginning

2. The End of the Beginning

3. The Beginning of the End

4. The End of the End12

As project managers, we typically take an idea from inception to a point at which it can be handed over to operations. If you make the analogy to Mulisch’s book, you could say that we manage projects from the beginning of the beginning (if we are lucky) to the end of the beginning—that point when the project’s product is ready to venture into its steady-state life. We don’t necessarily think of the project in its steady state, or decline, or disposal. But to address sustainability, the project manager should be thinking things through to the end of the end. Although it’s beyond the scope of this chapter to provide the details, we think one way for project managers to learn how to do this is to at least gain familiarity with a tool called a life-cycle assessment (LCA), which enables the estimation of the cumulative environmental impacts—impacts from the entire life cycle of the product of your project. It takes into account those many situations in which treatment of one environmental impact causes another one instead. From a project management perspective, we can think of the LCA as a tool to aid us in better risk identification and treatment, which goes beyond the traditional boundaries of our project thinking and yields a holistic and higher quality set of risks and even advice on how to treat them. Many LCA software tools exist to aid in this highly quantitative form of life-cycle analysis. (Many resources for learning how to apply an LCA are available on the EPA’s LCA resources site: http://www.epa.gov/nrmrl/std/lca/resources.html.)

CONCLUSION

If the material above seems far removed from your own job as project manager, here are five things you can do right now:

1. Accept the idea that you are a change agent. Projects are already all about change. The slogan “be the change you want to see in the world” (sometimes attributed to Mahatma Gandhi) applies here.

2. Connect your organization’s environmental management plan to your project’s objectives. This is one of the ways in which you can affect change. Use the statements and assertions your own enterprise is making as justification for sustainability considerations in your project and the projects’ product. This can include ensuring that your project is using a sustainability-oriented procurement plan.

3. Dare to think beyond the delivery of your project’s product to the sponsor. In fact, dare to think beyond that sponsor. This is part of what is already an increased discipline-wide focus on stakeholder management. Dig deeper, look further, and search more voraciously for stakeholders, and let sustainability concerns assist you in the search.

4. Understand the concept of greenality: ask yourself when planning, “How do quality and sustainability mesh on this project?”

5. Build your own credibility. As you look at job postings, you will see that sustainability is a “hot button.” Building your vocabulary in the area of environment, corporate social responsibility, and the triple bottom line makes you a more valuable employee.

![]() Does your company have sustainability policies? What are they? Look them up. How can you apply them to project planning?

Does your company have sustainability policies? What are they? Look them up. How can you apply them to project planning?

![]() Who else in your department, company, or project team is interested in these issues? Connect with others to accelerate your impact. Join the PMI Community of Practice for Global Sustainability (http://sustainability.vc.pmi.org/Public/Home.aspx) or the Linked In group Green PM. See you there!

Who else in your department, company, or project team is interested in these issues? Connect with others to accelerate your impact. Join the PMI Community of Practice for Global Sustainability (http://sustainability.vc.pmi.org/Public/Home.aspx) or the Linked In group Green PM. See you there!

![]() Look around your office. How many aspects of the furnishings, lighting, equipment, and amenities are wasteful/toxic? Make a list. Start with the things you can control.

Look around your office. How many aspects of the furnishings, lighting, equipment, and amenities are wasteful/toxic? Make a list. Start with the things you can control.

REFERENCES

1 Sources for this research are too numerous to list. To get up to speed, try NASA at http://climate.nasa.gov/, or the University of New South Wales’s Climate Change Research Center at http://www.ccrc.unsw.edu.au/news/newsindex.html.

2 Doyle Rice, “Hurricane Sandy, drought cost U.S. $100 billion,” USA Today online, posted January 24, 2013, www.usatoday.com/story/weather/2013/01/24/...sandy.../1862201/. See also Andrew Steer, “Listening to Hurricane Sandy: climate change is here,” Bloomberg.com, posted November 2, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-11-02/listening-to-hurricane-sandy-climate-change-is-here.html.

3 “Idea: triple bottom line,” The Economist Online, posted November 17, 2009, http://www.economist.com/node/14301663.

4 Juliet Eilperin, “Five takeaways from President Obama’s climate speech,” The Washington Post Online, posted June 25, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2013/06/25/5-takeaways-from-president-obamas-climate-speech/.

5 International Standards Organization, ISO 14000—Environmental Management, http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/management-standards/iso14000.htm.

6 “Environmental Sustainability,” Walmart Corporate website, http://corporate.walmart.com/global-responsibility/environment-sustainability.

7 National Academy of Sciences, “Assessing impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico,” ScienceDaily.com, posted July 10, 2013, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/07/130710122004.htm.

8 Richard Maltzman and David Shirley, Green Project Management (New York: CRC Press, 2012).

9 Natural Step, “The Four System Conditions of a Sustainable Society,” http://www.naturalstep.org/the-system-conditions.

10 William McDonough and Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (New York, NY: North Point Press, 2010).

11 Maltzman and Shirley, p. 130.

12 Harry Mulisch, The Discovery of Heaven (New York: Penguin Books, 1997).