CHAPTER 32

The Project Management Office

Trends and Tips

Gartner predicted in 2001 that companies that failed to establish a project management office (PMO) would experience twice as many major project delays, overruns, and cancellations as would companies with a PMO in place.1 Since then, we have seen the percentage of companies implementing PMOs skyrocket, with research indication that they had become valued organizational fixtures,2 followed in 2013 by a spate of negative studies questioning their value.3 What’s really going on with the PMO?

A decade ago, we theorized that what was then commonly termed the “project office” would become a valued player at the strategic corporate level.4 That strategic project office has since surpassed our wildest expectations. Our experience with finalists and winners of the PMO of the Year award has shown us that PMOs—whether evolved from the grassroots or implemented from the top down—have become indispensable centers of insight and services in companies, nonprofit organizations, and government.5

Center of excellence, strategic project office, enterprise program management office, enterprise project services—today’s PMO goes by many names and appears within our organizations in many roles. Attempts to gauge the effectiveness of this relatively new organizational entity run up against these different conceptions of the PMO, which exhibit varying spans of control, missions, functions, and process maturity.

Recently, there are been several attempts to apply process maturity modeling and language to measure the effectiveness of PMOs. The most detailed of these has been the PMO maturity cube. A full description of the cube is available at the website cited in the reference list. Its developers began from the assumption that “the better the PMO delivers its services, and only the ones related to the needed functions, the more the PMO is perceived delivering value to its organization.”6 The cube model goes on to posit twenty-one possible types of PMO and to deliver a complex scoring system to ascertain what a PMO’s scope, approach, and maturity of service delivery might be.

Working with PMO leaders, corporate leadership, and consultants in the field made us concerned that a model of such complexity might not be accessible for the average organization that needs to quickly compare itself to others in the industry, receive feedback on whether its PMO was performing the types of functions that are common to high-performing PMOs, and make plans for organizational improvement. We questioned whether, in fact, the complexity of measuring PMO value was perhaps one factor that fed into negative assessments of the PMO’s contributions.

In fact, we reasoned, restating the core assumption, that “a PMO delivers optimum business value to the sponsoring organization when its role—whether strategic, tactical, or operational—is guided by corporate strategy, and when its functions are selected and refined based on data about how well these functions contribute to strategy execution/goal achievement.” Such value is not—or, in our view, should not be—“perceived,” but rather should be measured and objective.

Was this reasoning realistic? In an effort to provide a structure for identifying and naming PMOs that is based on the business value they offer to their sponsoring organizations, PM Solutions Research then sought the input of focus groups drawn from PMO of the Year award finalists, as well as leaders of PMOs identified as “high performers” in the State of the PMO 2012, to develop a prototype model for PMO classification.

THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT OFFICE UNIVERSE

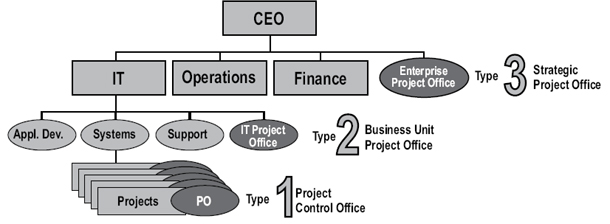

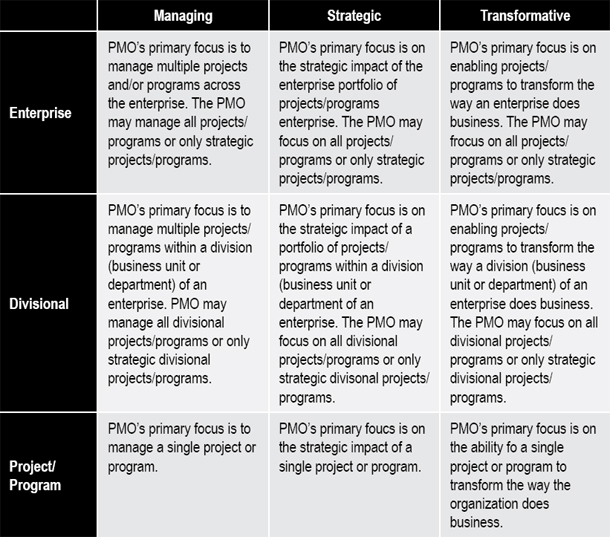

The first task was to develop a system of classifying PMOs, beginning with the descriptions offered in The Strategic PMO, 2nd edition (Figure 32-1). This system of three types works as a high-level kind of sorting mechanism to differentiate PMOs based on their span of control in the organization. Here are the descriptions of their roles:

Type 1: The Project Control Office. This is an entity that typically handles large, complex single projects (such as a Euro conversion project, or the creation of a new type of airplane). It is specifically focused on one project, but that one project is so large and so complex that it requires multiple schedules, which may need to integrate into an overall program schedule. It may have multiple project managers who are each independently responsible for an individual project schedule. As those individual schedules, and their associated resource requirements and associated costs, are all integrated into an overall program schedule, one program manager or a master project manager is responsible for integrating all of the schedules, resource requirements, and costs to ensure that the program as a whole meets its deadlines, milestones, and deliverables.

Type 2: Business Unit PMO. At the divisional or business unit level, a PMO may still be required to provide support for individual projects, but its challenge is to integrate a large number of multiple projects of varying sizes, from small short-term initiatives that require few resources to multi-month or multi-year initiatives requiring dozens of resources, large dollar amounts, and complex integration of technologies. The value of the Type 2 PMO is that it begins to integrate resources at an organizational level, and it is at the organizational level that resource control begins to play a much higher value role in the payback of a project management system. At the individual project level, applying the discipline of project management creates significant value to the project because it begins to build repeatability—the project schedule and the project plan become communication tools among the team members as well as within and among the organizational leadership.

FIGURE 32-1. THREE TYPES OF A PROJECT OFFICE

At Type 2 and higher, the PMO serves that function but also begins to provide a much higher level of efficiency in managing resources across projects. Where there are multiple projects vying for a systems designer, for example, the Type 2 PMO has project management systems established to de-conflict that competing need for a common resource and identify the relative priorities of projects. Thus, the higher priority projects receive the resources they need and lower priority projects are either delayed or canceled. A Type 2 PMO allows an organization to determine when resource shortages exist and to have enough information at their fingertips to make decisions on whether to hire or contract additional resources. Since the Type 2 PMO exists within a single department, conflicts that cannot be resolved by the PMO can easily be escalated to a department manager or organizational vice president, who has ultimate responsibility for performance within his or her organization.

Type 3: Strategic PMO. Consider an organization with multiple business units, multiple support departments at both the business unit and corporate level, and ongoing projects within each unit. A Type 2 project office would have no authority to prioritize projects from the corporate perspective, yet corporate management must select projects that will best support strategic corporate objectives. These objectives could include strategic initiatives, revenue generation opportunities, cost reduction programs, productivity enhancements, and profitability contribution, to name just a few. Only a corporate-level organization can provide the coordination and broad perspective needed to select, prioritize, and monitor projects and programs that contribute to attainment of corporate strategy—and this organization is the strategic PMO. At the corporate level, the strategic or enterprise PMO serves to de-conflict the need for competing resources by continually prioritizing the list of projects across the entire organization. Obviously, this cannot be done by the strategic PMO in isolation; thus the need for a steering committee made up of the strategic PMO director, corporate management, and representatives from each business unit and functional department.7

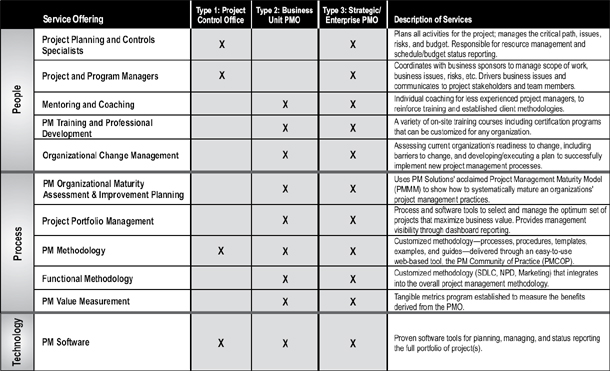

The common capabilities of these various types of PMO are shown in Table 32-1.

TABLE 32-1. CAPABILITIES OF VARIOUS TYPES OF PROJECT OFFICE

FIGURE 32-2. THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT OFFICE (PMO) UNIVERSE

Discussion with our focus group members led us to further refine these types and rename them. Figure 32-2 shows a prototype of PMO classification based on span of control plus organizational role/mission. Since several focus group members described the existence of informal or nascent (under development) PMOs in their organization, we originally added the Type 0 category—given that the goal of the model is to accurately describe the workday reality of PMOs. However, as the concept continued to evolve to focus on the capability of the PMO, Type 0 was dropped, recognizing that informal PMOs usually exist to initiate the development of capability but probably do not themselves display it.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT OFFICE AREA OF FOCUS: THE MISSION OR ROLE DEFINED BY THE ORGANIZATION

A primary source for information about the day-to-day world of PMOs has been our series of biennial research studies, The State of the PMO. Inaugurated in 2007 and repeated in 2010 and 2012, these survey-based studies are beginning to show trends in the development of the PMO as an organizational structure. For example, in 2008, a minority of PMOs functioned as enterprise-wide entities; this percentage had increased dramatically by 2012 to 41 percent.8 In seeking to accurately depict PMOs’ role in organizations, we sifted through the data compiled over 2007 to 2012, looking for key changes in the roles played by PMO. As the developers of the PMO cube also discovered, the picture is complex. Here are some findings:

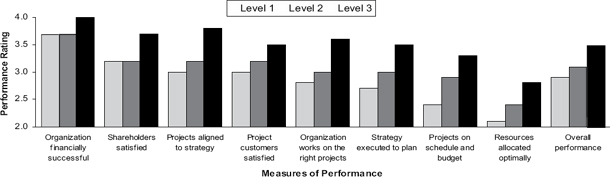

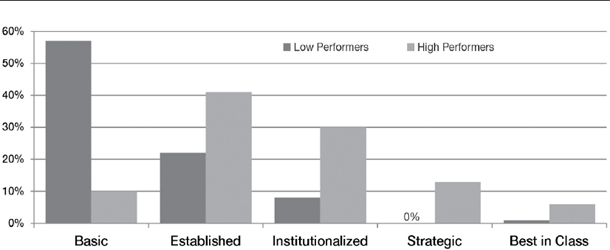

• Project management offices are becoming more mature; the number moving from level 1 to level 3 in self-reported project management (PM) process maturity increased between 2007 and 2010, and the more mature PMOs represented organizations that scored higher on eight measures of organizational performance (Figure 32-3). Maturity was self-reported on a scale from level 1 to 5 (immature, established, grown up, mature, best in class). Only maturity levels 1 to 3 are shown in the figure, since too few PMOs reported at levels 4 and 5. “High performance,” also self-reported, is defined as higher on a scale of 1 to 5 of how well the overall organization performs in the eight measures of performance shown in the figure, along with a measure of overall performance.

• While PMO age does correlate with maturity and capability, even new PMOs (less than one year since inception) frequently show up in the “high-performing organization” category.

• Even PMOs with a single-program focus frequently describe their role as “strategic,” while information technology (IT) (divisional) PMOs frequently report managing enterprise-wide programs.9

Clearly, the idea of a progressive improvement in maturity tracking with increasing levels of responsibility or organizational scope was not in tune with PMO realities. In discussing this with PMO leaders in our focus group and during qualitative research interviews with respondents to the State of the PMO 2012 study, we heard over and over again that the very idea of “levels” of PMO was flawed. Here are a few of their comments:

• “ ‘Level’ says that you start at the bottom and work your way up incrementally, starting with basic project management and adding more and more strategic roles. That isn’t necessarily the case. In our company, the PMO came in as a strategic entity tasked with transforming the organization. It wasn’t until several years passed that we actually hands-on managed projects.”

• “Stay away from the word ‘level’—it has a judgmental overtone. In fact, a ‘level 1’ PMO that focuses only on managing projects may be the exact PMO that is perfect for delivering the business results the company requires. There is no ‘up’ from there.”

• “ ‘Level’ implies progression or hierarchy and that’s not what that is.”10

Taking our lead from this input, we conceptualized the “PMO universe” shown in Figure 32-2, one in which a PMO might operate:

• As a single megaproject and yet be transformative in nature for the organization as a whole.

• At the divisional level, and yet be involved in strategic initiatives.

• At the enterprise level providing project managers and project management expertise across functional boundaries, and be purely focused on managing, without participating in strategy formulation or other strategic or transformative roles.

These roles are described in more detail in Table 32-2. The model is circular because, in the real world, there isn’t a clear, step-by-step progression in the changing PMO role and impact. An organizational structure can be implemented, for example, by experts called in to create it and jump-start it, without growing that structure from the internal grassroots. Today’s organizations often grow by leaps through merger or acquisition, or discontinuously, as when a new chief information officer makes radical changes to divisional structure and processes.

FIGURE 32-3. ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE BY LEVEL OF PMO MATURITY

Source: The State the PMO 2010, PM Solutions Research, 2010.

TABLE 32-2. THREE AREAS OF FOCUS FOR PMOs

We called these “classes” of PMOs to make it clear that one is not better than the other, except in terms of individual organizational needs. We envisioned individual companies being able to scope a PMO that crossed all the boundaries shown, by incorporating to a greater or lesser degree the functions that might be typical of a particular class. As we discussed what made a great PMO, we heard again and again from our focus group and interviewees that the only lens through which a PMO’s effectiveness should be viewed was the organization-specific lens of capability; that is, does the PMO perform those functions that add business value to their sponsoring organization?

PROJECT MANAGEMENT OFFICE CAPABILITIES

Again referring to the State of the PMO research, we found that high-performing organizations had PMOs that offered a wider range of functions and services (Figure 32-4). The PMOs in organizations that scored as “high performing,” based on eight measures of organizational performance, offered more functions and services than those in low-performing organizations.

FIGURE 32-4. PMOs IN HIGH-PERFORMING ORGANIZATIONS

Source: The State of the PMO 2012.

However, referring to notes from interviews and focus groups, we were struck by comments such as the following:

• “If you stretch too thin and do things poorly, then it’s not true [that offering more functions adds value]. Instead the model should show that as you increase what you can do for your organization—via more functionality—more benefits accrue to your organization.”

• “It’s not that we are trying to roll out PPM [project portfolio management] or not roll out PPM—as a services organization, it’s driven by the client and funded by the client, so PPM isn’t that important to us in the classical sense. Our mission is to further integrate with the business, understand the strategic goals of the business, and develop tools and processes that serve those goals.”

• “We don’t see the world as ‘things we need to do as a PMO’ but as ‘things we can do as an organization to help the company sell more products and services.’”11

Obviously, these PMO leaders were speaking with the voice of experience, reminding us that functional capability alone is not what matters; the PMOs should offer and refine only those functions or services that directly impact the business outcomes for their organization.

How do PMOs identify which functions and services these are? And what can they do to optimize the performance of these functions? We defined the ability to identify the correct functions, and to optimize them in concert with meeting business goals, as “capability”: the ability to deliver those functions and services that are required to execute strategies, and to deliver them in ways that contribute to measurable performance improvements. To that end, we identified eight key PMO functional capabilities:

• Project management

• Program management

• Performance management

• Demand management/resource management

• Vendor management

• Change management

• Integration management

In addition, with the assistance of our focus groups, we identified four “capability enablers” that can support (or hinder) PMO capability in any of the above areas, for any type of PMO, no matter what its organizational mission:

• Governance/structure

• People/culture

• Process

• Technology

The assessment method for the degree of effectiveness of each of these continues to be under development and validation.

To recap: the PMO capability model operates as a classification system to help standardize the nomenclature of PMOs. At present, there is a wide range of organizational entities referred to as “PMOs.” This model will help to clarify the terminology and assist organizations in understanding where their present or planned practices fit into the “universe” of PMOs operating in the marketplace. We felt—and our interviews confirmed—that this would be of practical assistance to PMO leaders. One interviewee remarked, “Most of us here . . . have some challenges communicating what we are trying to do. In trying to describe our PMO, we’ve struggled for the right language—are we hybrid? Guerilla? We need to be able to make a business case for moving the PMO out of IS [information systems].”12 This focus on the business case has provided the lens through which we view PMOs and their many roles. The resulting model is descriptive, not prescriptive; that is, its emphasis is on defining your PMO as it stands now, and where you want it to be based on your specific business goals. It provides a “menu” of possibilities to aspire to that may be pulled from various types of PMOs.

The PMO capability model focuses on capability instead of maturity because, while a process improves incrementally and can be measured against a continuum, the capabilities of an organizational entity may improve via breakthroughs (hiring consultants, acquisitions, new technology). Thus the PMO model is not in levels, but by classes—with PMOs able to straddle two or more classes, depending on the business needs they serve and the services they offer.

How can this be important? An organization may attain process maturity and still not be delivering the value-adding services that the executive needs or desires. By focusing on capability we seek to keep the discussion rooted in practical business functions and outcomes. Think of it in terms of an “elevator speech”: the PMO director may say to the CEO, “We achieved level 5 in PMMM (project management maturity model)!” and still get the response, “But what are you capable of doing for us today?” A transformative EPMO (enterprise project management office) leader, on the other hand, might be able to say, “We offer the following sources of business value, which we developed in response to strategic requirements.”

PROJECT MANAGEMENT OFFICE IN PLACE? DON’T RELAX YET

A trend that first surfaced in 2002 at the Project Management Benchmarking Forums, and which has continued to plague PMOs despite increasing organizational clout, visibility, and proven value added, was of companies that had achieved a mature project management process under the auspices of an enterprise PMO, but which were disinvesting in project management in the name of cost-cutting exercises.

Forum participants—representatives of project management practices within some of America’s top corporations—described the expressed opinions of their executive leadership as paradoxical: on the one hand they claimed to support and value project management; on the other hand they were slashing project management office budgets and cutting training for project managers. In a tight economy, management identified the entire project management exercise as an overhead expense.

Ironically, the most successful and long-standing project management offices may be the most vulnerable to cost cutting because the organization takes good project management for granted. An article in Computing Canada by HMS Software president Chris Vandersluis characterized the attitude as “Can’t we just do all of this in Excel like we used to?” and “The projects aren’t a problem; why do we spend so much money on managing them?”13

Once implemented, good project management becomes invisible and, paradoxically, that can be a problem. The effects of good change management, good planning, resource capacity planning, and variance management mean that projects just seem to run themselves. Management forgets that the costs associated with maintaining a project management structure are outstripped by the potential costs of having no project management structure. Vandersluis describes the PM-free environment as “projects that run late and over budget . . . a mismatch of resources to projects . . . clients [and] suppliers are unhappy . . . shareholders are unhappy . . . ,” and boldly states that “losing the efficiency that comes with a corporate-wide project management environment can take a company from barely profitable to completely unprofitable in a short period of time.”

PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT: THE MISSING LINK

In reviewing the in-depth background research provided by Pinto et al,14 one statistic stuck us as particularly meaningful. In a 2007 study, it was determined that the function of 50 percent of the PMOs studied was to “monitor and control their performance.” Only 50 percent? It may seem striking that only half of PMOs put systems in place to monitor their own performance, yet this result has been borne out by the State of the PMO studies. As recently as February 2012, this number is still only 50 percent, although 54 percent report that they plan to focus on improving or implementing performance measurement within that year.15 In terms of identifying areas for improvement in capability, or identifying where capability could be better enabled, a lack of PMO performance measurement is a serious gap. The “instability” in PMO tenure noted by Pinto et al may very well be related to the failure of PMOs to tell executive management an “elevator story” that aligns with their most pressing concerns.

Project management office directors and managers often wonder out loud why processes like accounting are accepted as costs of doing business, while the project management process constantly struggles for survival on the organizational edge. The constant effort to make visible to management costs they didn’t incur saps energy that would be better spent on managing projects. But this vigilance is simply part of the requirements for maintaining your PMO, once established, as a visible and appreciated part of organizational life.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

![]() What types of PMO exist in your organization, if any? How would you classify them in terms of focus?

What types of PMO exist in your organization, if any? How would you classify them in terms of focus?

![]() Which of the “capability enablers” work well in your organization? Which are lacking—or even hinder PMO success?

Which of the “capability enablers” work well in your organization? Which are lacking—or even hinder PMO success?

![]() Again, for a company you are familiar with, consider ways that centralizing project management across the enterprise might streamline decision making. In particular, focus on communication and information sharing between departments and levels of management.

Again, for a company you are familiar with, consider ways that centralizing project management across the enterprise might streamline decision making. In particular, focus on communication and information sharing between departments and levels of management.

REFERENCES

1 M. Light and T. Berg, Gartner Strategic Analysis Report: The Project Office: Teams, Processes and Tools, August 1, 2000.

2 PM Solutions Research, The State of the PMO 2012 (Glen Mills, PA: PM Solutions, 2012).

3 The Hackett Group, “Most Companies with Project Management Offices See Higher IT Costs, No Performance Improvements,” posted November 1, 2012, http://www.thehackettgroup.com/about/research-alerts-press-releases/2012/11012012-research-details-factors-behind-failure-pmos.jsp. Also see J. Leroy Ward, “The Life Expectancy of a PMO,” posted 26 March 2012, http://www.wardwired.com/2012/03/the-life-expectancy-of-a-pmo/.

4 J. Kent Crawford, The Strategic Project Office (Boca Raton, FL: Auerbach/CRC Press, 2001).

5 PM Solutions Research, 2012 PMO of the Year Award ebook, http://www.pmsolutions.com/resources/view/pmo-of-the-year-award-2012-ebook/.

6 A. Pinto, M. Cota, and G. Levin, The PMO Maturity Cube, A Project Management Office Maturity Model, Presented at the PMI Research and Education Congress 2010, Washington, DC, http://www.pmomaturitycube.org/arquivos/PMOMaturityCubeEng.pdf, p. 16.

7 J Kent Crawford and Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, The Strategic Project Office, 2nd edition (Boca Raton, FL: Auerbach/CRC Press, 2011): pp. 31–33.

8 PM Solutions Research, The State of the PMO 2007–2008 (Glen Mills, PA: PM Solutions, 2008); The State of the PMO 2010 (Glen Mills, PA: PM Solutions, 2010); and PM Solutions Research, The State of the PMO 2012 (Glen Mills, PA: PM Solutions, 2010).

9 PM Solutions Research, 2008, 2010, 2012.

10 PM Solutions Research, Focus Group Proceedings, January 4, 2012. Unpublished.

11 PM Solutions Research, Focus Group Proceedings, 2012.

12 PM Solutions Research, Qualitative Interviews, follow-up to State of the PMO survey, March, 2012.

13 Chris Vandersluis, “Cutting project office is detrimental to corporate health,” Computing Canada, September 2002.

14 Pinto et al, op cit., p. 1.

15 PM Solutions Research, State of the PMO 2012.