CHAPTER 3

Project Management Process Groups

Project Management Knowledge in Action

The project management profession’s standard, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), is described as consisting of ten knowledge areas. What is left out of this description is the equally important segment of the standard that describes the processes used by the project manager to apply that knowledge appropriately.

The ten knowledge areas can be effectively arranged in logical groups for ease of consistent application. These process groups are initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing. They describe how a project manager integrates activities across the various knowledge areas as a project moves through its life cycle. So, while the knowledge areas within the standard describe what a project manager needs to know, the process groups describe what steps the project managers must take and the approximate order of those steps.1 Historically, the definition of the processes that make up the project management body of knowledge was a tremendous milestone in the evolution of project management as a profession. Understanding the processes as described in the PMBOK® Guide is a first step in mastering project management.

However, as the practice of this profession matures, our understanding of its processes will also mature and evolve. This is reflected in the additions and changes made in successive editions of the standard over the years.

In 2000 edition of the PMBOK® Guide, processes were divided into two classifications that were essentially virtual groupings of the project management knowledge areas: core processes and facilitating processes.2 This classification provided a focus to guide project managers through the application of the knowledge areas and to help in implementing the appropriate ones for their projects. However, a clear differentiation between the core processes and facilitating processes was not provided. Project managers also needed information about when and how to use the processes in those classifications. Subsequently, many inexperienced project managers used the differentiation to focus only on the core processes; they addressed the facilitating processes only if time permitted. After all, the latter processes were merely “facilitating” processes.

Therefore, a key change was made in 2004 in the third edition of the PMBOK® Guide that was maintained throughout subsequent editions. The artificial focus classifications of core processes and facilitating processes were removed, and since then all of the processes within the knowledge areas are treated equally in the PMBOK® Guide.3 In order to understand this, it is important to know that a process is a set of activities performed to achieve defined objectives. All project management processes are equally important for every project; there are no unimportant processes. A project manager uses knowledge and skills to evaluate every process and to tailor each one as needed for each project. This tailoring is required because there has never been a “one size fits all” project management approach; this is especially important when integrating Agile techniques into a project management process. Every company and organization faces different constraints and requirements on each project. Therefore, tailoring must be performed to ensure that the competing demands of scope, time and cost, and quality are addressed to fulfill those constraints and requirements. Some processes can require a stronger focus on quality and time while also minimizing cost, which is an interesting project management challenge.

The odds of a project being successful are much higher if a defined approach is used when planning and executing it. The project manager chooses an approach for the project’s specific constraints after the tailoring effort is completed. This approach must cover all processes needed to adapt, capture, and analyze customer interests, plan and manage any technology evolution, define product specifications, produce a plan, and manage all the activities planned to develop the required product.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS GROUPS

Project management process groups are a logical way to categorize and implement the knowledge areas. The fifth edition of the PMBOK® Guide recommends addressing every process group for every project. However, the tailoring and rigor applied to implementing each process group are based on the complexity of, and risk for, the specific project.4 The project manager uses the process groups to address the interactions and required trade-offs among specified product requirements to achieve the project’s final product objective. These process groups may appear to be defined as a strict linear model. However, a skilled project manager knows that a project is iterative in nature. Furthermore, artifacts like the business case statement, preliminary plan, and scope statements are rarely complete in their first drafts. Therefore, in most projects, the project manager must iterate through the various processes as many times as needed to define the requirements and then to refine the project management plan that is used to produce a product that meets its requirements. This iteration activity can be done as a series of sprints or iterations to drive to the final deliverable.

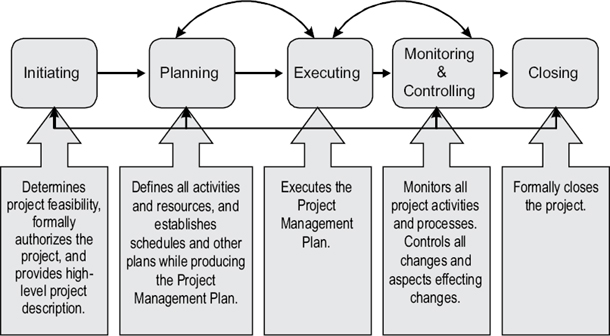

Project managers iteratively perform the activities within the process groups on their projects as shown in Figure 3-1, which illustrates how the output of one process group provides one or more inputs for another process group, or even how an output may be the key deliverable for the overall project.

FIGURE 3-1. PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS GROUPS’ INTERACTIONS

These process groups are tightly coupled since they are linked by their inputs and outputs. This coupling makes it clear that the project manager must ensure that each process is aligned with the other processes for a successful project. When managing a successful project, the process groups and their interactions provide a specific outcome from the application of the project management knowledge areas. A project manager skilled in applying these knowledge areas never confuses the process group interactions with the phases in a product life cycle and is able to apply the interactions in the process groups to drive a project life cycle to its successful completion.

Many project managers have been involved with a project that was started without appropriate analysis and preparation and then ended up costing the company a significant amount over its budget. A case in point: a high-level manager at a customer site might mention an idea to someone in a development company and that idea hits a spark. The company takes the idea and launches into production. When the finished product is completed, there is surprise all around. The customer does not remember any request for this product and the production company cannot sell it to anyone else. The following issues are apparent in this scenario:

• It is not clear whether the idea expressed a valid need.

• It is not clear whether there were real or imagined requirements.

• It is not clear if there was an analysis of a return on investment.

• It is not clear whether there was a delivery date.

• It is not clear whether needed resources were pulled from other projects or if there was impact on other schedules.

• It is not clear that a market need was established prior to development.

The initiating process group is required to answer these types of questions and to formally begin project activities.5 The project manager uses the initiating processes to start the project by gathering and analyzing customer interests and then addressing any issues or risks and project specifics. The project manager must iterate through the needed initiation activities to identify the service or product requiring the project’s effort. The organization must take a critical look at the feasibility and technical capability of creating the product or service as the requirements become more refined. After the appropriate analysis, a project charter is produced that addresses at a minimum the following issues:

• It provides formal authorization for the project.

• It provides a high-level description of the product or service that will be created.

• It defines the initial project requirements, constraints, and assumptions. The constraints and assumptions typically provide the initial set of negotiating points for the project plan.

• It designates the project manager and defines the project manager’s authority level.

• It specifies any hard delivery dates if those dates are required by the contract.

• It provides an initial view of stakeholder expectations.

• It provides an indication of the project budget.

The project manager works with the customer to capture the customer’s interests and analyze them to develop the initial scope statement. Typically, content detail varies depending on the product’s complexity or the application area. This document provides a high-level project definition and should define the project boundaries and project success criteria. It should also address project characteristics, constraints, and assumptions.

The documents developed during this series of processes are provided as input to the planning effort. A plan is a tool that can be used like a map. Unfortunately, some project managers learn a hard lesson about the importance of a defined project plan. A plan is not just a way to focus on tasks; it is a tool to focus efforts and accomplish what is required by the due date. The plan is used to keep the project on track so that the project manager and the team know where the project is in relation to the plan, and they can work together to determine the next steps, especially if discovery is needed. Attempting to run a project without a plan would be like trying to travel to a destination via an unknown route, not knowing one’s current location and having no indication of which direction to take. In such a situation, even a map would be useless.

Additional confusion is introduced when some project managers confuse the Gantt chart, which is defined by commercial tools as a “project plan,” with an actual project management plan as defined in the fifth edition of the PMBOK® Guide.6 A real project management plan provides needed information about the following:

• Which knowledge area processes are needed, how each is tailored for this particular project, and especially how rigorously each of those processes will be implemented in the project

• How the project team will be built from the resources across the organization or will be brought in through contract, hiring of full-time employees, or outsourcing

• Which quality standards will be applied to the project, and the degree of quality control that will be needed for the project to be successful

• How risks will be identified and mitigated

• Which method will be used for communicating with all of the stakeholders to facilitate the timing of their participation to facilitate addressing open issues and pending decisions

• Which configuration management requirements will be implemented and how they will be performed on this project

• A list of scheduled activities, including major deliverables and their associated milestone dates

• The budget for the project based on the projected costs

• How the project management plan will be executed to accomplish the project objectives, including the required project phases, any reviews, and the documented results from those phases or reviews

Planning is the central activity the project manager continues performing throughout the project. The plan is iteratively revisited at multiple points in the project. Every aspect of the project is impacted by the project management plan or, conversely, impacts the plan. The plan provides input to the executing processes, to the monitoring and controlling processes, and to the closing processes. If a problem occurs, the planning activities can even provide input back to the initiating activities, which can cause a project to be re-scoped and to have a new delivery date authorized. The project manager integrates and iterates the executing processes until the work planned in the project management plan has produced the required deliverables. The project manager uses the project management plan and manages the project resources to perform the work to produce the project deliverables. During execution, the project manager also facilitates the quality assurance activities. The project manager also ensures that approved change requests are implemented by the project team. This effort ensures that the product and project artifacts are modified only per the approved changes. The project manager communicates status information so that the stakeholders will know the project status, which activities have been started or are finished, and which activities are late. Key outputs from executing the project management plan are the deliverables for the next phase and the final deliverables to the customer.

The project manager uses monitoring and controlling processes to observe all aspects of the project. These processes help the project manager proactively know whether or not there are potential problems so corrective action can be started before a crisis results. Monitoring project execution is important, because a majority of the project’s resources are expended during this phase. Monitoring includes collecting data, assessing the data, measuring performance, and assessing measurements. This information is used to show trends and is communicated to show performance against the project management plan.

Configuration management is an essential aspect of establishing project control. Therefore, configuration management is required across the entire organization, including procedures that ensure that versions of the project are controlled and that only approved changes are implemented. The project implements aspects of change control necessary to continuously manage changes to project deliverables. Some organizations implement a change control board to formally address change approval issues to ensure the project baseline is maintained by only allowing approved changes into the documentation or product.

Project managers must integrate their monitoring and controlling activities to provide feedback to the executing process. Some of this information feeds back to the planning process. However, if there is a high-impact change to the project scope or overall plan, then there will also be input to the initiating processes.

The closing processes require the project manager to develop any procedures required to formally close a project or a phase.7 This group of processes covers the transfer of the completed product to the final customer and project information to the appropriate organization within the company. The procedure also covers the closure and transfer of an aborted project and any reasons the project was terminated prior to completion.

The process groups described above represent the standard processes defined by the fifth edition of the PMBOK® Guide and required for every project.8 These processes indicate when and where to integrate the many knowledge areas to produce a useful project management plan. Those processes, when executed, produce the result defined by the project’s scope.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

![]() During which project management process are risk and stakeholders’ ability to influence outcomes the highest at the beginning of the process?

During which project management process are risk and stakeholders’ ability to influence outcomes the highest at the beginning of the process?

![]() You are a project manager for a major copier company. You are heading up a project to develop a new line of copiers. You are ready to write the scope statement. What should it contain?

You are a project manager for a major copier company. You are heading up a project to develop a new line of copiers. You are ready to write the scope statement. What should it contain?

![]() You are a project manager working on gathering requirements and establishing estimates for the projects. Which process group are you in? How does knowing this clarify the steps you need to take to perform your assigned tasks?

You are a project manager working on gathering requirements and establishing estimates for the projects. Which process group are you in? How does knowing this clarify the steps you need to take to perform your assigned tasks?

REFERENCES

1 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 3rd edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2004), p. 30.

2 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, (PMBOK® Guide), 2000 edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2000), p. 29.

3 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2013), p. 49.

4 Ibid., p. 46.

5 Ibid., p. 54.

6 Ibid., p. 55.

7 Ibid., p. 56.

8 Ibid., p. 52.