CHAPTER 13

Human Resource Management

The People Side of Projects

Virtually every organization recognizes the importance of people—their attitudes, skills, personal efforts and collaboration. In project environments, where time and resource effectiveness are critical components of performance, this is especially obvious.1–8 Yet managing people effectively is very difficult. It is especially challenging in today’s complex business environment, with many operations distributed across the globe. This requires working with people from different support organizations, vendors, partners, customers, and government agencies; it requires effective networking and cooperation among organizations with different cultures, values and languages.9–15 Thus, managers today must be capable of dealing effectively with economic, political, social, and regulatory issues, and the associated uncertainties and risks.16–18

Many of the issues involved in managing people overlap between functional and project management since the project organization is generally an overlay to the functional organization, which project managers depend on for many of their needed resources. (Note: Although organizational charts are one of the aspects of human resource management covered in the chapter on human resource management in the Project Management Institute’s Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), we will not discuss types of organization here, as these charts were covered in Chapter 5.)

WHAT DRIVES PROJECT-BASED PERFORMANCE?

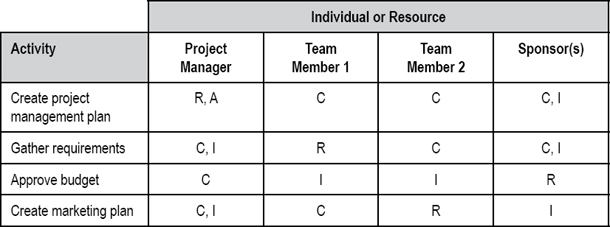

Project managers often describe their organizational environments as “unorthodox,” with ambiguous authority and responsibility relations. The multidisciplinary settings common to projects create a unique organizational culture with its own norms, values, and work ethics, requiring broader management skill sets and more sophisticated leadership than do traditional business situations. These cultures are more team-oriented regarding decision making, work flow, performance evaluation, and work group management. Authority must often be earned and emerges within the work group as a result of credibility, trust, and respect, rather than organizational status and position. Rewards come to a considerable degree from satisfaction with the work and its surroundings, with recognition of accomplishments as important motivational factors for stimulating enthusiasm, cooperation, and innovation. Tools such as the RACI matrix (Responsible, Accountable, Consult, Inform) help project managers to understand the complex interplay among stakeholders (Table 13-1). Understanding who is responsible and/or accountable for various project tasks, as well as who it is important to consult or inform about project progress, is an important first step for leading project teams and dealing with sponsors and customers.

Source: Adapted from Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2013), p. 262.

TABLE 13-1. EXAMPLE RACI MATRIX TEMPLATE

While overall project performance is determined by a complex array of variables, the importance of teamwork and team management cannot be overstated. This is why the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) standard chapter on human resource management describes the major process areas as follows:

• Plan human resources management: identify project roles and responsibilities, as well as the skills needed and the reporting relationships. Tools such as resource calendars, skills database, and competency assessments assist the project manager in this planning.

• Acquire project team: confirm the availability of appropriately skilled individuals, and obtain their commitment. This may involve negotiation skills or interface with procurement processes when outsourced talent is required.

• Develop project team: address competency, interpersonal skills, and building an environment conducive to achievement.

• Manage project team: track team member performance, provide feedback, resolve conflicts, facilitate meetings, and support team members in achieving personal, team, and project success.19

Such a “team-centered” management style is based on the thorough understanding of the motivational forces and their interaction with the enterprise environment. (Note: Team building, conflict resolution, and other related skills are covered in detail in Chapter 39.)

HOW TO MOTIVATE AND INSPIRE

Leaders who succeed in project environments must work with cross-functional groups and gain services from personnel not reporting directly to them. They have to deal with line departments, staff groups, team members, clients, and senior management, each having different cultures, interests, expectations, and charters. Transforming these multidisciplinary groups into cohesive teams is difficult. To get results, these project leaders must relate socially as well as technically, and understand the culture and value system of the organization in which they work. It is no longer possible for managers to get by with only technical expertise or pure administrative skills.

What works best? Observations of best-in-class practices show consistently and measurably three important characteristics of high-performing project teams: (1) team members enjoy work and are excited about the contributions they make to their company and society; (2) they feel confident about their assignment regarding the overall probability of success, their perception of the risks involved, their lack of personal embarrassment and anxiety, and their mutual trust and respect; and (3) they have their professional and personal needs fulfilled.

MOTIVATION AS A FUNCTION OF RISKS AND CHALLENGES

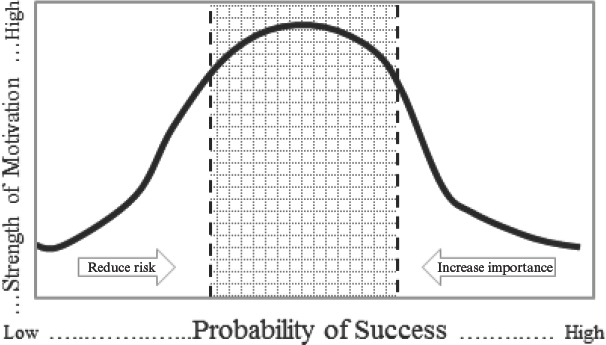

Motivational strength is a function of the probability and desire to achieve the goal. Understanding this fundamental model of human behavior is critical to motivating people on project assignments that are often challenging or less desirable for many reasons. Personal motivation toward reaching a goal changes with the probability of success (perception of doability) and challenge.20 Figure 13-1 expresses the relationship graphically. A person’s motivation is very low if the probability of achieving the goal is very low or zero. As the probability of reaching the goal increases, so does motivational strength. However, this increase continues only up to a level where the goal is still seen as desirable and challenging. When success is more or less assured, motivation often decreases. This is an area where work is often perceived as routine, uninteresting, and holding little potential for professional growth. The challenge is for team leaders to build an image of low risk and high professional interest by showing the team, for example, that the project is well planned, resourced, and supported, and emphasizing the importance of the outcome to the enterprise and society, and the excitement of working on this project and its mission.

FIGURE 13-1. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROBABILITY OF SUCCESS AND STRENGTH OF MOTIVATION

HIGH-PERFORMANCE TEAM LEADERSHIP

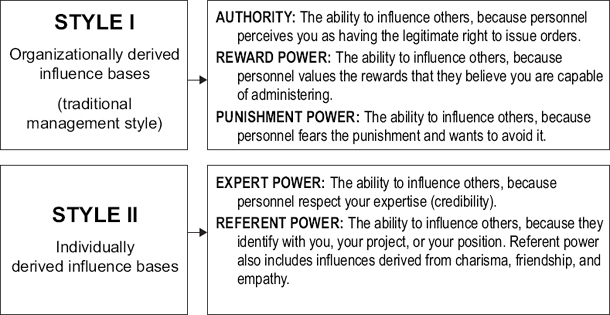

As organizations have become flatter, leaner, more agile, and self-directed, they share responsibilities, resources, and power to a greater extent. Today’s project organizations rely extensively on cross-functional teamwork, including multi-company alliances and complex forms of work integration with member-generated performance norms and work processes. Self-directed team concepts are gradually replacing the traditional, more hierarchically structured organization,21,22 requiring a radical departure from traditional management practices of top-down, centralized command, control, and communications. To be effective, project managers have to direct their personnel and obtain cross-functional support without much organizationally derived power. They must develop, or “earn,” their own bases of influence and build their own power spectrum, which derives from personal knowledge, expertise, and the image of a sound decision maker. The basic concept of power and authority has been known for a long time. Four decades ago, French and Raven23 presented a typology that included five bases of interpersonal power: authority, reward, punishment, expertise, and referent power (i.e., friendship, charisma, empathy), which are summarized in Figure 13-2. To this day, these are still the most commonly recognized influences of managerial power. For some time, the first three bases—authority, reward, and punishment—were perceived as being derived entirely from the organization. However, more recent studies provide measurable evidence that all bases of power can be individually developed, at least to some degree. (For a fuller discussion of power and politics in project organizations, see Chapter 34.)

FIGURE 13-2. COMMON BASES OF MANAGERIAL INFLUENCE

Today’s organizations grant power to their leaders in many forms. Some of it is still derived from the organizational construct and vested in the leader via organizational position, status, and other traditional components of legitimacy, including the power to mete out rewards and discipline. However, contemporary project managers must earn most of their authority and influence bases for managing their multifunctional teams. Since earned authority depends largely on the image of trust, respect, credibility, and competence, it is strongly influenced by the manager’s ability to foster a work environment in which the team feels comfortable, accomplishes results, and receives recognition, and the team members have their professional and personal needs met.24 This includes images of managerial expertise, friendship, work challenge, promotional opportunities, fund allocations, charisma, personal favors, project goal identification, recognition, and visibility of the work and its importance.

Rewards are very important bases of managerial power. They must be used judiciously, consistent with the employee’s output, efforts, and contributions, and fair and equitable across the organization. Effectively, employee communication, such as explaining the rationale for any financial award, which is supported with well-earned recognition of the accomplishments, is a good starting point for optimizing the motivational benefits of financial and other types of rewards.

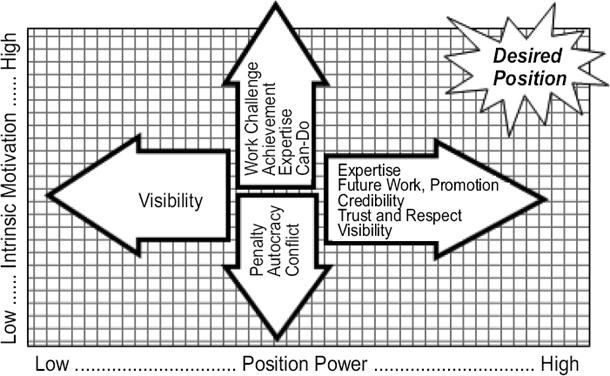

Motivation, and the project manager’s ability to influence it, is not necessarily fixed or stable, but changes with the work environment and team dynamics. This situational dependency is graphically shown in Figure 13-3. It shows that intrinsic motivation increases with the manager’s emphasis on work challenge, expertise, and ability to provide professional growth opportunities. On the other hand, emphasis on penalties and authority, and the inability to manage conflict, lowers team members’ motivation. Project managers who can foster a climate of high motivation not only obtain greater support from their personnel, but also achieve high overall performance ratings from their superiors.

FIGURE 13-3. HOW ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS INFLUENCE MOTIVATION

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR WORKING EFFECTIVELY WITH PEOPLE ON PROJECTS

The following suggestions are valid for any project situation. However, projects of higher complexity require an even stronger focus on the human side of management and more sophisticated leadership. This is particularly true in high-tech environments, where the work culture favors expert power, individual autonomy, and creativity.

1. Clear task assignment: At the outset of any new assignment, managers and project leaders should discuss with their staff/team members the overall task and its scope, timing, resources, deliverables, and objectives.

2. Early project/mission involvement and ownership: A thorough understanding of the task requirements comes usually with intense personal involvement, which can be stimulated through participation in project planning, requirements analysis, interface definition, or feasibility studies. Involvement of the team members during the early phases of the assignment, such as bid proposals and project planning, can produce great benefits toward plan acceptance, realism, buy-in, personnel matching, and unification of the task team.

3. Priority image: Management should clearly articulate the importance of the assignment and its impact on the company and its mission. Senior management can help develop such a “priority image” by their involvement and by effectively communicating key mission parameters. The relationship and contribution of individual work to overall business plans, as well as of individual project objectives and their importance to the organizational mission, must be clear to all personnel.

4. Team image: Building a favorable image for an ongoing project and its team, in terms of high priority, interesting work, importance to the organization, high visibility, and potential for professional rewards is crucial for attracting and holding high-quality people. Senior management can help develop a priority image and communicate clear top-down objectives, building an image of high visibility, importance, priority, and interesting work.

5. Effective project planning and team structure: Formal planning, using proven tools and techniques, early in the life cycle of a project is critical to any project success. These plans and their methods don’t have to be far out, but should be effective in defining the basic team structure and cross-functional linkages for effective project execution. This requires the participation of the entire multidisciplinary team, including support departments, subcontractors, and management.

6. Professionally stimulating work: Whenever possible, managers should try to accommodate the professional interests and desires of their personnel. Interesting and challenging work is a perception that can be enhanced by the visibility of the work, management attention and support, priority image, and the overlap of personnel values and perceived benefits with organizational objectives. Making work more interesting leads to increased involvement, better communication, lower conflict, higher commitment, stronger work effort, and higher levels of creativity.

7. Senior management engagement: It is critically important that senior management provide the proper environment for a technology team to function effectively. Early in the project life cycle the project manager should negotiate the needed resources with the sponsor organization, and obtain commitment from management that these resources will be available. An effective working relationship among resource managers, project leaders, and senior management critically affects the credibility, visibility, and priority image perceived by the project team.

8. Clear communication: Poor communication is a major barrier to teamwork and effective performance. In addition to technology tools, such as voice mail, email, electronic bulletin boards, and conferencing, management can facilitate the free flow of information, both horizontally and vertically, by work space design, regular meetings, reviews, and information sessions. Further, well-defined interfaces, task responsibilities, reporting relations, communication channels, and work transfer protocols can greatly enhance communications within the work team and its interfaces, especially in complex organizational settings.

9. Leadership positions: Leadership positions should be carefully defined and staffed for all projects and support functions. Especially critical is the credibility of project leaders among team members, with senior management and with the program sponsor, for the leader’s ability to manage multidisciplinary activities effectively across functional lines.

10. Reward system: Personnel evaluation and reward systems should be designed to reflect the desired behavior and focus of the people on the team. Rewards should encompass the whole spectrum of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators, and reward both individual and team performance.

11. Problem resolution: Project managers should focus their efforts on problem identification and early problem solving. That is, managers and team leaders, through experience, should recognize potential problems and conflicts at their onset, and deal with them before they become big and their resolutions consume a large amount of time and effort.

12. Personal drive and leadership: Managers can influence the work environment by their own actions. Concern for the team members, the ability to integrate personal needs of their staff with the goals of the organization, and the ability to create personal enthusiasm for a particular project can foster a climate of high motivation, work involvement, open communication, and ultimately high team performance.

CONCLUSION

Managerial leadership has significant impact on the work environment, affecting project personnel and performance. Other important influences include effective communications among team members and support units across organizational lines, good team spirit, mutual trust and respect, low interpersonal conflict, and opportunities for career development and job security. These conditions serve as a bridging mechanism between personal and organizational goals, helpful in building a unified project team capable of producing integrated results in support of the organization’s mission.

Taking a bird’s-eye look at the people side of project management, the following three recommendations stand out as particularly important to effective role performance:

1. Understand motivational needs. Project managers need to understand the interaction of organizational and behavioral elements in order to build an environment conducive to their personnel’s motivational needs. Two conditions seem to be especially critical to high performance: professional interest and work support. However, identifying and satisfying these needs across a complex diversified work group is challenging and requires special techniques and skills. Conventional tools, such as focus groups, action teams, suggestion systems, open-door policies, and management-by-wandering-around, complemented with computer-aided tools, such as PeopleSoft and online surveys, can provide a useful framework for identifying and profiling the needs of various segments of the project team.

2. Accommodate professional interests, and build enthusiasm and excitement. Project managers should try to accommodate the professional interests and desires of their personnel when negotiating tasks and during the execution. This leads to employee ownership and commitment, resulting in increased involvement, better communication, lower conflict, stronger work effort, and higher levels of creativity. Equally important, factors that satisfy professional interests and needs strongly effect team unification and overall project performance. While the scope of the work group may be fixed, the manager has the flexibility of allocating task assignments among various members. Well-established practices, such as front-end involvement of team members during the project planning or proposal phase and one-on-one discussions are effective tools for matching team member interests and project needs.

3. Adapt leadership to the situation. Because their environment is temporary and often untested, project managers should develop a leadership style that allows them to adapt to the dynamics of their organizations, support departments, customers, and senior management. They must learn to “test” the expectations of others by observation and experimentation. Leading a technology team can rarely be done “top down,” but requires a great deal of interactive team management skills and senior management support. Although difficult, managers must be able to alter their leadership style as demanded by the specific work situation and its people. This is particularly important in the increasingly prevalent use of virtual teams, where the ability of the manager to communicate is not facilitated by collocation at a work site. Not only the virtual team member but also the project manager must adjust his or her methods of setting clear expectations, giving feedback, resolving conflict, and sharing information.

![]() How can managers and team leaders “earn” their authority, especially when crossing functional lines and dealing with organizations over which they have no formal authority?

How can managers and team leaders “earn” their authority, especially when crossing functional lines and dealing with organizations over which they have no formal authority?

![]() Discuss the characteristics of effective project teams. How could you measure team effectiveness? How can you develop these qualities?

Discuss the characteristics of effective project teams. How could you measure team effectiveness? How can you develop these qualities?

![]() Thinking of the issues involved in working virtually, what are some of the ways the project manager can support and include virtual team members?

Thinking of the issues involved in working virtually, what are some of the ways the project manager can support and include virtual team members?

REFERENCES

1 D. Anconda and H. Bresman, X-Teams: How to Build Teams That Lead, Innovate and Succeed (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing Company, 2007).

2 “The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable,” Academy of Management Perspectives, 20 (2006), pp. 122–125.

3 I. Kruglianskas and H. Thamhain, “Managing technology-based projects in multinational environments, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 47, No. 1 (2000), pp. 55–64.

4 A. Nurick and H. Thamhain, “Team Leadership in Global Project Environments,” in David I. Cleland (editor), Global Project Management Handbook (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002).

5 B. Schmid and J. Adams, “Motivation in project management: a project manager’s perspective,” Project Management Journal 39, No. 2 (2008), pp. 60–71.

6 A. Shenhar, “What great projects have in common,” MIT Sloan Management Review 52, No. 3 (2008), pp. 19–21.

7 S. Sidle, “Building a committed workforce: does what employers want depend on culture?” Academy of Management Perspectives 23, No. 1 (2009), pp. 79–80.

8 H. Thamhain, “Critical success factors for managing technology-intensive teams the global enterprise.” Engineering Management Journal 23, No. 3 (2011), pp. 30–36.

9 D. Armstrong, “Building teams across borders,” Executive Excellence 17, No. 3 (2000), pp. 10–11.

10 H. Barkema, J. Baum, and E. Mannix, “Management challenges in a new time,” Academy of Management Journal 45, No. 5 (2002), pp. 916–930.

11 R. Barner, “The new millennium workplace,” Engineering Management Review (IEEE) 25, No. 3 (1997), pp. 114–119.

12 A. Bhatnager, “Great teams,” Academy of Management Executive 13, No. 3 (1999), pp. 50–63.

13 C. Gray and E. Larson, Project Management (New York: Irwin McGraw-Hill, 2000).

14 A. Shenhar, “What great projects have in common,” MIT Sloan Management Review 52, No. 3 (2011), pp. 19–21.

15 H. Thamhain, “Criteria for Effective Leadership in Technology-Oriented Project Teams,” in Slevin, Cleland, and Pinto, The Frontiers of Project Management Research (Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2002), pp. 259–270.

16 R. Keller, “Cross-functional project groups in research and new product development,” Academy of Management Journal 44, No. 3 (2001), pp. 547–556.

17 S. Manning, S. Massini, and A. Lewin, “A dynamic perspective on next-generation offshoring: the global sourcing of science and engineering talents,” Academy of Management Perspectives 22, No. 3 (2008), pp. 35–54.

18 H. Thamhain, “Managing globally dispersed R&D teams.” International Journal of Information Technology and Management (IJITM) 8, No. 1 (2009), pp. 107–126.

19 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2013).

20 M. Hoegl and K. Parboteeah, “Team goal commitment in innovative projects,” International Journal of Innovation Management 10, No. 3 (2006), pp. 299–324.

21 D. Cleland and L. Ireland, Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007).

22 J. Polzer, C. Crisp, S. Jarvenpaa, and J. Kim, “Extending the fault line model to geographically dispersed teams,” Academy of Management Journal 49, No. 4 (2006), pp. 679–692.

23 J. French and B. Raven, “The basis of social power,” in D. Cartwright (editor), Studies in Social Power (Ann Arbor: Research Center for Group Dynamics, 1959), pp. 150–165.

24 H. Thamhain, “Team leadership effectiveness in technology-based project environments,” IEEE Engineering Management Review 36, No. 1 (2008), pp. 165–180.