CHAPTER 28

Performance and Value Measurement for Projects and Project Management

Project managers excel at managing projects but have not always been very good at communicating the value of what they do. Often, the steps involved in measuring performance and value are omitted in the drive to “just get it done.”

However, this is short-sighted. It is imperative that both projects and project management track and communicate performance. More than ever, investment in initiatives designed to improve organizational performance must be justified. Whether it’s the implementation of a project management methodology, a project management office (PMO), project management software, or project management training, these initiatives must deliver positive and tangible results. The good news is that tangible measures of project management value and performance can be established by asking the right questions and developing an appropriate measurement system.

TWO LEVELS OF MEASUREMENT

The first measurement level is more familiar and more frequently carried out. Project managers are used to tracking budget and schedule performance. The missing step, however, is in relating these outcomes to the business impacts they provide. In communicating these impacts, we can demonstrate the value of project management processes. This key step is absent in many PMOs, which may be the reason why some PMOs have been disbanded during tough economic times.1

A structured measurement program enables you to identify areas for performance improvement, benchmark against the industry or competitors, set targets, identify trends for forecasting and planning, evaluate the effectiveness of changes, determine the impact of project management, and tell a story about your organization’s performance.

CREATING A MEASUREMENT PROGRAM

Measuring performance and value takes time and commitment. Senior management sponsorship is crucial, and there needs to be a sense of urgency about the results. Above all, make sure you have the resources to gather and analyze the data.

Common goals and objectives to measure include the following:

• Reducing costs

• Improving timing

• Improving quality

• Measuring the effectiveness of training

• Improving productivity

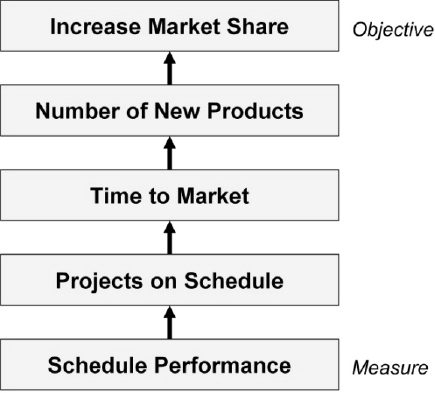

Choose a measurable outcome that is important to your company. For example, if improving schedule performance for all your projects over a period of a year can be translated into improvement in average project cycle time, this can be translated into improvement in time to market. Shorter time-to-market means that your organization launches more products in a given period, which can add significant value to the organization’s bottom line. Value measures, therefore, provide information on the performance of the organization rather than the performance of a project. This example also demonstrates how good measures should align with organizational objectives. Figure 28-1 shows how schedule tracking metrics can lead, through careful linkage with organizational objectives, to a measurement of business value for your project management practice.

Measurement: Making the Connection

When schedule performance has been linked to increased market share, the value of training project personnel in scheduling becomes calculable. In this same way, it is possible to work backward from any strategic goal, drilling down to those measurable tasks that have an impact on goal achievement, and then developing training plans that directly impact those tasks. Using a measurement program of this type, the training function will always have a “hard” answer ready to this question: Does this training pay off? And, by how much?2

A Model for Performance Measurement

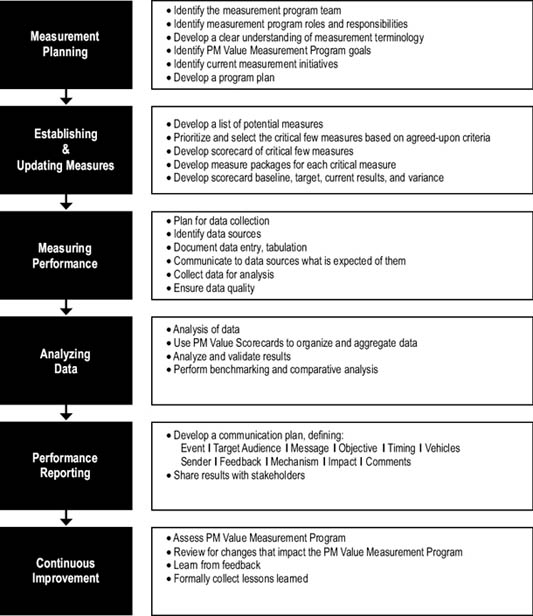

A model established by Project Management Solutions has been proven to work well in dozens of organizations. This model, known by the acronym PEMARI, integrates the following processes:

• Planning: a process for understanding key success factors, identifying stakeholders and roles and responsibilities, identifying performance management goals, and developing a program plan

• Establishing metrics: a process for identifying and selecting performance measures and developing measurement scorecards (high-level measures are defined at the governance level; specific metrics that roll up into these measures are identified at the departmental or program level)

FIGURE 28-1. FROM PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT TO VALUE.

• Measurement: a process for planning for data collection, including data source and information technology (IT) required; collecting data and ensuring data quality (a joint responsibility of IT and the strategic project office [SPO] as owner of the portfolio processes)

• Analysis: a process for converting data into performance information and knowledge; analyzing and validating results; performing benchmarking and comparative analysis (a joint responsibility of IT and the SPO)

• Reporting: a process for developing a communications plan and communicating performance results to stakeholders (a responsibility of internal communications)

• Improvement: a process for assessing performance management practices, learning from feedback and lessons learned, and implementing improvements to those practices (a joint responsibility of the SPO as portfolio owner, and executives responsible for governance)3

Developing Performance Measures

While there is general agreement that “you can’t manage what you can’t measure,” the actual measurements themselves usually prove to be a source of conflict. What are we measuring, and why? What should we be measuring? What is the connection between the performance measures we collect regarding individuals and their tasks and the ultimate performance of the company—if any? And what, in reality, does “performance” mean, on an organization-wide scale? Is it merely making money? And if so, how much? Measures are the easy part; knowing what you want to measure, and why, is hard.

There is no single set of measures that universally applies to all companies. The appropriate set of measures depends on the organization’s strategy, technology, and the particular industry and environment in which they compete. Like any aspect of any “living company,” measures cannot be static: they cannot be chosen once and locked into place. Along with strategy, they evolve and are refined as the organization becomes more focused on, and skilled at, meeting strategic goals.

Measurement Planning

Planning your performance measurement program begins with identifying the measurement program team and its roles and responsibilities, and defining measurement program goals. Next, identify what, if any, current performance measurement systems are in place. What will be your implementation approach? Like any program, a measurement program needs a program plan and a clear understanding of terminology among the team members. Some suggested roles on the measurement team are as follows:

• Sponsor

• Representatives from stakeholders

• Project manager

• Data collection coordinator

• Data analyst

• Communications coordinator

• Measurement analyst

Establishing and Updating Measures

To develop a list of potential measures, start by brainstorming all the possible measures that would be meaningful to the goals you are trying to achieve. These criteria describe effective measures:

• Does this measure provide meaningful information?

• Is it supported by valid, available data?

• Is it cost-effective to capture?

• Is it acceptable to stakeholders?

• Is it repeatable? Actionable?

• Does it align with organizational objectives?

Next, prioritize and select a few critical measures, keeping the number of measures at each management level to a minimum. A few criteria for prioritization of measures might include their importance to the execution of goals, the ease of accessing the data, and the ease of acting to change the performance.

This process leads to the development of a scorecard of vital measures, with each measure clearly defined as a “measure package” that details the “what, why, when, who, and how”:

• What is the measure?

• Why do we measure it?

• How will the data be captured?

• When will the data be captured?

• Where does this information reside?

• Who is the process owner for this data?

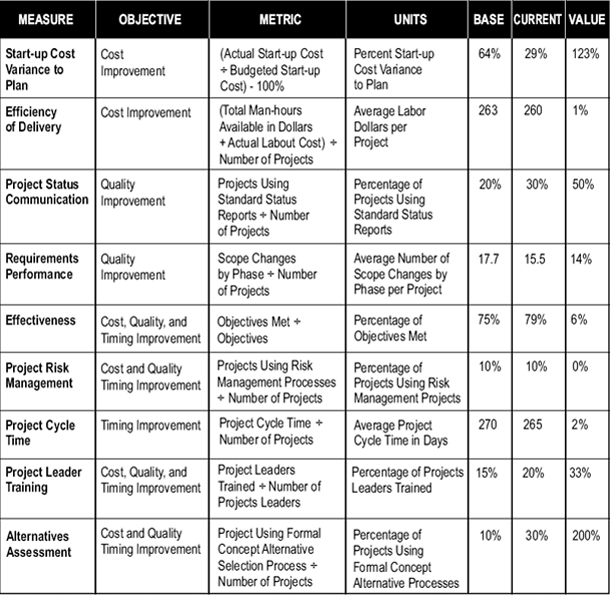

A sample list of prospective measures is shown in Figure 28-2. Here are detailed descriptions of what we have identified as the “top ten” measures:

1. Return on investment: (Net Benefits/Costs) × 100. This is the most appropriate formula for evaluating project investment (and project management investment). This calculation determines the percentage return for every dollar you have invested. The key to this metric is in placing a dollar value on each unit of data that can be collected and used to measure net benefits. Sources of benefits can come from a variety of measures, including contribution to profit, savings of costs, increase in quantity of output converted to a dollar value, and quality improvements translated into any of the first three measures.

2. Productivity: Output Produced/Unit of Input. Productivity measures tell you whether you are getting your money’s worth from your people and other inputs to the organization. A straightforward way to normalize productivity measurement across organizations is to use revenue per employee as the key metric. Dividing revenue per employee by the average fully burdened salary per employee yields a productivity ratio for the organization as a whole. Other productivity metrics might be the number of projects completed per employee and the number of lines of code produced per employee. The key to selecting the right productivity measures is to ask whether the output being measured (the top half of the productivity ratio) is of value to your organization’s customers.

3. Cost of quality: Cost of Quality/Actual Cost. Cost of quality is the amount of money a business loses because its product or service was not done right in the first place. It includes total labor, materials, and overhead costs attributed to imperfections in the processes that deliver products or services that do not meet specifications or expectations. These costs would include inspection, rework, duplicate work, scrapping rejects, replacements and refunds, complaints, loss of customers, and damage to reputation.

4. Cost performance index (CPI): Earned Value/Actual Cost. The CPI is a measure of cost efficiency. It is determined by dividing the value of the work actually performed (the earned value) by the actual costs that it took to accomplish it. The ability to accurately forecast cost performance allows organizations to confidently allocate capital, reducing financial risk, possibly reducing the cost of capital.

5. Schedule performance: Earned Value/Planned Value. The schedule performance index is the ratio of total original authorized duration versus total final project duration. The ability to accurately forecast the schedule helps meet time-to-market windows.

6. Customer satisfaction: Scale of 1 to 100. Meeting customer expectations requires a combination of conformance to requirements (the project must produce what it said it would produce) and fitness for use (the product or service produced must satisfy real needs). The customer satisfaction index comprises hard measures of customer buying/use behavior and soft measures of customer opinions or feelings, weighted based on how important each value is in determining customer overall customer satisfaction and buying/use behavior. It includes measures such as repeat and lost customers, revenue from existing customers, market share, customer satisfaction survey results, complaints/returns, and project-specific surveys.

7. Cycle time: There are two types of cycle time—project cycle and process cycle. The project life cycle defines the beginning and the end of a project. Cycle time is the time it takes to complete the project life cycle. Cycle times for similar types of projects can be benchmarked to determine a standard project life-cycle time. Measuring cycle times can also mean measuring the length of time to complete any of the processes that comprise the project life cycle. The shorter the cycle times, the faster the investment is returned to the organization. The shorter the combined cycle time of all projects, the more projects the organization can complete.

8. Requirements performance: To measure this factor, you need to develop measures of fit, which means the solution completely satisfies the requirement. A requirements performance index can measure the degree to which project results meet requirements. Types of requirements that might be measured include functional requirements (something the product must do or an action it must take) and nonfunctional requirements (a quality the product must have, such as usability or performance). Fit criteria are usually derived some time after the requirement description is first written. You derive the fit criterion by closely examining the requirement and determining what quantification best expresses the user’s intention for the requirement.

9. Employee satisfaction: An employee satisfaction index (ESI) determines employee morale levels. The ESI comprises a mix of soft and hard measures, each assigned a weight based on its importance as a predictor of employee satisfaction levels. Examples include the following (percentages represents weight): climate survey results (rating pay, growth opportunities, job stress levels, overall climate, extent to which executives practice organizational values, benefits, workload, supervisor competence, openness of communication, physical environment/ergonomics, trust)—35%; focus groups (to gather in-depth information on the survey items)—10%; rate of complaints/grievances—10%; stress index—20%; voluntary turnover rate—15%; absenteeism rate—5%; and rate of transfer requests—5%.

10. Alignment to strategic business goals: Most project management metrics benchmark the efficiency of project management—doing projects right. You also need a metric to determine whether or not you are working on the right projects. Measuring the alignment of projects to strategic business goals is such a metric. Survey the appropriate mix of project management professionals, business unit managers, and executives. Use a Likert scale from 1 to 10 to rate the following statement: Projects are aligned with the business’s strategic objectives.4

Analyzing the Data

Use a scorecard method to organize and aggregate the data, grouping measures by their relationship to key organizational areas of concern, such as financial measures, customer satisfaction measures, process measures, and employee satisfaction measures. In order to analyze and validate results, you must formulate precise questions that you are trying to answer. To validate your results, ask these questions:

FIGURE 28-2. SAMPLE LIST OF MEASURES IN “SCORECARD” FORMAT

• How does actual performance compare to a goal or standard?

• If there is significant variance, is corrective action necessary?

• Are new goals or measures needed?

• How have existing conditions changed?

Performance Reporting

Like any communications, performance reporting requires early identification of your target audience. Normally, with a measurement program, this will be executives, sponsors, PMO leaders, line-of-business managers, and other key stakeholders.

Relate the data to the organization’s management performance goals and, where possible, to departmental and individual performance goals. Explain significant results, such as increases or decreases. The way you communicate results can be almost as important as the results themselves.

Continual Improvement

Measurement, like any organizational improvement initiative, cannot be done just once. Having baselined your measurements, you will have to iteratively measure in order to develop trends. In addition, linking the measurement program to a system of accountability for results creates a sense of urgency and relevance.

Once you start measuring performance, you can begin to start measuring value.

THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT VALUE MEASUREMENT SYSTEM: LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

From 2000 to 2005, major companies from a variety of industries—information technology, manufacturing, pharmaceutical, new product development, government, and professional services—initiated projects to create measurement programs to measure the value that project management provides to their organizations. The goals of these project management measurement programs were as follows:

• Provide tangible metrics to senior management on the value of implementing systematic project management methods in order to reinforce the business case for project management improvement across the organization.

• Boost customer and project team members’ morale by sharing statistics that show the value their work adds to the organization and the improvement they can achieve.

• Track ongoing project management performance and the business impact of project management to the organization.

• Initiate metric-based efforts to help streamline the project portfolio.5

Phase one focused on educating a measurement team on the Project Management Value Measurement Program to help them understand and enable them to clearly identify the program’s objectives and goals. Organizational constructs that affect the program were identified, including stakeholders, organizational mission and strategies, organizational structure, key business processes, project management maturity, prior project management improvement initiatives, current measurement systems, and data availability.

Phase two focused on planning the initiative and engaging the team to identify measures, develop a project management value scorecard, and plan the implementation of the measurement program. After putting a project management value initiative plan and schedule in place, subsequent steps in this phase continue to build on the team’s understanding of the project management measurement program and engage the team to develop the value scorecard and the project management value implementation plan.

Measures Development

In the measures development step, the team created and prioritized the initial list of measures for the scorecard. It is the initial pass at identifying and prioritizing measures, with the primary activity in the step being a collaborative development workshop. A comprehensive list of measures was developed, keeping in mind that they need to be logically linked to the goals described above. The measures also need to meet the criteria for good measures, which means that the measures selected must:

• Provide meaningful information.

• Be supported by valid data that are cost-effective to capture.

• Be acceptable to stakeholders.

• Be repeatable.

• Be actionable.

• Align with organizational objectives.

The measurement team then prioritized and selected measures to comprise the project management value scorecard. A simple prioritization process can be used: develop criteria for ranking the list of measures in order of importance on a scale of 1 to 5, have each of the measurement team members rank the list, and calculate average rankings.

Scorecard Development

In this step the team reviewed the prioritized measures information developed to date and developed measure packages (see below) and a cohesive project management value scorecard. The team first engaged in measures review, prioritization validation, and measure package definition. That information is then used to construct the scorecard for review and acceptance by the measurement team in preparation for implementation.

A comprehensive definition of each measure is included in a “measure package” to support the initial implementation and ongoing collection of data. Each measure package includes the following elements:

• Measure (What): The data to be collected must be clearly identified.

• Objective (Why): The measure’s objective must be clearly defined. Why is it being collected? How will it be interpreted? What will it tell us? The measurement team must understand the objective of each measure.

• Data capture (How): The mechanism for collecting the data must be identified.

• Timing (When): The timing of data collection must be defined. Data collection must be properly timed to match the type of data and objective. Project management value measures are not intended to track individual project progress, so there would most likely not be a need to collect data monthly. Typically a quarterly or longer interval will support the objectives of the initiative.

• Data location (Where): The location of the data must be identified.

• Data contact (Who): The person responsible for maintaining the data must be identified. Who will provide the data? What is the reliability of this source?

Information from the measure packages is used to create a project management value scorecard, which is a collection and reporting tool for keeping score and reporting progress (Figure 28-3).

Measurement Program Implementation Planning

The implementation planning efforts further defined the framework around measurement processes and data collection that will be used to support ongoing measures program implementation. Key activities in this step include development of an implementation strategy and process. The Project Management Value Measurement Program process shown in Figure 28-4 describes a systematic approach to project management performance improvement through an ongoing process of establishing project management measures; collecting, analyzing, reviewing, and reporting performance data; using that data to drive performance improvement; and using lessons learned to continually improve the Project Management Value Measurement Program process.

FIGURE 28-3. SAMPLE PM VALUE SCORECARD

Phase three includes an initial implementation of the program and the transition to ongoing execution of the program.

The Project Management Value Measurement Program implementation is an ongoing effort to execute the program as documented in the implementation plan, using the measures packages to reinforce the data requirements, collection timing, and data contact responsibilities.

LESSONS LEARNED

• Organizational strategies and objectives set the foundation for effective measurement programs. It is essential to understand how the critical elements of the organization’s strategies and objectives are linked to the measures that comprise the project management value scorecard.

• You need to have a very clear idea of the measurement program stakeholders and what their needs and expectations are regarding the program. There are often huge differences in expectation among stakeholders; setting those expectations through clear communication of program goals is a key to success.

FIGURE 28-4. THE PM VALUE MEASUREMENT PROGRAM PROCESS

• Clearly identify measurement program goals and objectives. Without this clarity, selecting the right set of critical few measures will be difficult.

• In most best-in-class organizations, measurement initiatives are introduced and continually championed and promoted by top executives. When measurement initiatives are introduced from the bottom up, getting senior management buy-in is crucial and may take significant effort. Be prepared to make that effort.

• Develop a clear understanding of measurement terminology, which tends to be confusing and inconsistent, but needs to be understood and agreed upon by the measurement team and program stakeholders.

• Communication is crucial for establishing and maintaining a successful measurement program. It should be multidirectional, running top-down, bottom-up, and horizontally within and across the organization.

• The driving force to create a new or improved measurement program is usually a threat to the organization (often a crisis or strong competition). For organizations that are strategically developing measurement programs to enhance their competitive advantage, rather than reacting to their business environment, a sense of urgency must be nurtured and driven by individuals who understand the value of measurement and can evangelize the need for developing a measurement culture. Again, this takes enormous effort and communication.

• It is critical, and very difficult, to limit the number of measures in the scorecard. Selecting those critical few measures sharpens the stakeholders’ understanding of the issues. Too many measures confuse and complicate (the measurement team cannot try to please everyone—selecting too many measures will ultimately kill the program).

• Pilot the measurement program before full implementation. And implementation should come in phases—implement a critical few high-value measures at first and identify more detailed measures when the organization has developed a measurement culture and is ready to collect and analyze more complex measures.

• Successful deployment of a measurement program requires a successful system of accountability—that is, all stakeholders need to buy into measurement by assuming responsibility for some part of the measurement process (sponsorship, analysis, data collection and monitoring, evangelism, etc.).

• Benchmark against industry standards if possible.

• Identify a central area of responsibility for the measurement program.

• Determine what counts as a project (what exactly will be measured).

• Reinforce the fact that project management value measurement is measuring performance change due to project management. Measures, therefore, are process focused, not project focused (you are not trying to measure the progress of a particular project).

• The measures selected are highly influenced by the project management maturity of the organization. Level-one organizations generally need to focus on process compliance and simple cost or schedule measures. As the organization matures in its project management capability, more sophisticated measures can be used.

• Analysis is one of the most important steps in project management value measurement, yet it is often one that is neglected. The insight gained from effective analysis (particularly determining root causes of the results measured) is what makes measurement a valuable business tool.

• Feedback is one of the best assets for continual improvement. Seek it and use it.

![]() For an organization with which you are familiar, list the project management initiatives that have been implemented: tools, training, a project office, and so on. Did these initiatives solve the problems they were implemented to solve? If not, why not?

For an organization with which you are familiar, list the project management initiatives that have been implemented: tools, training, a project office, and so on. Did these initiatives solve the problems they were implemented to solve? If not, why not?

![]() Again, for an organization you are familiar with, what metrics are collected about project management performance? How are they used? Can you think of ways to improve metrics collection or development?

Again, for an organization you are familiar with, what metrics are collected about project management performance? How are they used? Can you think of ways to improve metrics collection or development?

![]() What barriers would have to be overcome in your organization in order to set up a value measurement system?

What barriers would have to be overcome in your organization in order to set up a value measurement system?

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The material in this chapter was originally presented on behalf of PM Solutions at the 2002 PMI Global Congress in the paper J. Oswald and J.S. Pennypacker, “The value of project management: the business case for implementation of project management initiatives,” Proceedings of the Project Management Institute Annual Seminars and Symposium, 2002.

REFERENCES

1 The Hackett Group, “Most companies with project management offices see higher it costs, no performance improvements.” News release posted November 1, 2012. See also “The global state of the PMO in 2011,” ESI, 2011, http://www.esi-intl.com/~/media/Files/Public-Site/US/Research-Reports/ESI-2011-PMO-global-survey-FULL-REPORT-US.

2 PM College, Building Project Manager Competency Improves Business Outcomes (white paper) (Glen Mills, PA: PM Solutions Research, 2012).

3 Deborah B. Crawford, Mastering Performance Measurement (white paper), PM Solutions, 2009.

4 PM Solutions, Measures of Project Management Performance and Value (Glen Mills, PA: Center for Business Practices, 2005), http://www.pmsolutions.com/audio/PM_Performance_and_Value_List_of_

Measures.pdf.

5 The PM Value system is a part of the performance measurement practice of Project Management Solutions, Inc. (www.pmsolutions.com).