CHAPTER 27

Enterprise Project Governance

Directing and Structuring Organizational Project Decisions

Projects and programs need alignment with strategic intent in order to enhance value creation and ultimately increase competitive advantage while, at the same time, mitigating risk. It is not only a matter of doing the projects right. It is not only a matter of doing the right projects. It is not only a matter of ensuring that the right combination of right projects is done right. It is also essential that the correct approach of oversight be applied to guarantee strategic differentiation and value creation through the right combination of right projects done right.

The evolution of project management, once relegated to tactical concerns, has reached the level of enterprise project governance (EPG)—the umbrella of policies and criteria that comprise the laws for the sundry components that make up an organization. Enterprise project governance takes the evolution a step further, encompassing an all-inclusive approach to projects across an enterprise, involving all players, including board members, the CEO and other C-level executives, portfolio managers, project management office (PMO) managers, and project managers.

Overall governance of projects includes the classic components of project management, such as portfolios, stakeholders, programs, and support structures. But EPG reaches beyond outstanding project performance and organizational pillars such as project management maturity and continuous improvement to embrace an enterprise-wide perspective, including the organizational risks, the essential issues, and the business opportunities.

HOW DOES ENTERPRISE PROJECT GOVERNANCE RELATE TO CORPORATE GOVERNANCE?

The increasing focus on corporate governance can be traced to the stock market collapse of the late 1980s, which precipitated numerous corporate failures through the early 1990s. The concept started becoming more visible in 1999 when the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released its “Principles of Corporate Governance.”1 Since then, over thirty-five codes or statements of principles on corporate governance have been issued in OECD countries.

The evolution of corporate governance was prompted by cycles of scandals followed by reactive corporate reforms and government regulations intended to improve the practice. Investors, unions, government, and assorted pressure groups are increasingly likely to condemn businesses that fail to follow the rules of good practice.

Increasing governance oversight structures is not an easy task. James Wolfensohn, former president of World Bank, stated:

A number of high profile failures in 2001–2002 have brought a renewed focus on corporate governance, bringing the topic to a broader audience. . . . The basic principles are the same everywhere: fairness, transparency, accountability, and responsibility. . . . However, applying these standards across a wide variety of legal, economic, and social systems is not easy. Capacity is often weak, vested interests prevail, and incentives are uncertain.2

The high visibility heaped on corporate governance sparked by the scandals at the beginning of the twenty-first century brought attention to the lack of governance policies in more specific disciplines. In the early 1990s, information technology (IT) executives perceived a crying need to put order into the then-chaotic industry. Various programs and standards were developed, such that IT governance has become a solid cornerstone of the profession. After the turn of the century, a similar need became evident in the burgeoning field of project management.

Thus, EPG is a natural evolution in organizations that wrestle with countless demands for new projects to be completed within tighter time frames, at less cost and with fewer resources.

The need for EPG becomes more apparent as the world becomes increasingly projectized. With more projects clamoring for attention, the demand to undertake, manage, and complete multiple projects creates a need to provide greater governance and structure to multiple decision layers. While corporate governance addresses the concerns of the ongoing organization, with its status quo activities and operational issues, EPG, under the corporate umbrella, focuses on the projectized parts of organizations.3

KEY COMPONENTS OF ENTERPRISE PROJECT GOVERNANCE

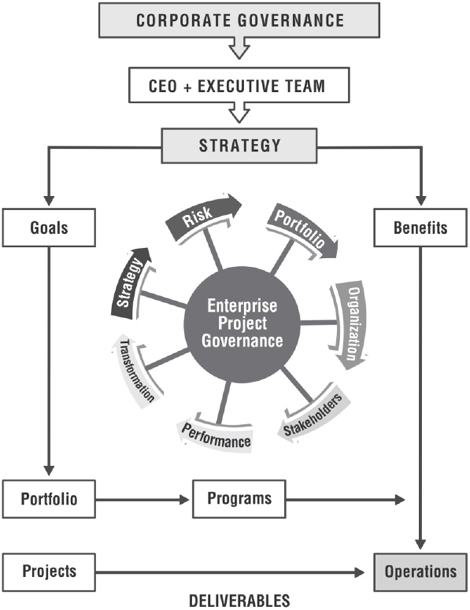

In fulfilling the EPG role, the key activities for project sponsors and steering committee members to address are strategic alignment, risk management, portfolio management, organization and stakeholder management, performance evaluation, and business transformation. Implementing project governance requires a framework based on these major components, as presented in Figure 27-1.

Strategic Alignment

The responsibility of EPG is to ensure that projects are consistent with company strategies and goals and that the projects are implemented productively and effectively. All investment activities are subject to the governance process in that they need to be resourced and financed adequately. For mandatory projects, the decision is not whether to undertake the project but how to manage it in order to meet the required standard with minimum risk. For discretionary projects, more focus is required on the go/no-go decision and whether the project supports the strategic objectives and the investment gives best value compared with other alternatives.

FIGURE 27-1. COMPONENTS OF ENTERPRISE PROJECT GOVERNANCE

Risk Management

Risk management is a systematic process of identifying and assessing risks and taking actions to protect a company against them. Organizations need risk management to analyze possible risks in order to balance potential gains against potential losses and avoid expensive mistakes. Risk management is best used as a preventive measure rather than as a reactive consequence. Managing risk in an integrated way can mean everything from using financial instruments to managing specific financial exposures, from effectively responding to rapid changes in the organizational environment, to reacting to natural disasters and political instability.

Portfolio Management

The project portfolio provides a big-picture view. It enables managers to become aware of all of the individual projects in the portfolio and provides a deeper understanding of the collection as a whole. It facilitates sensible sorting, adding, and removing projects from the collection. A single project inventory can be constructed containing all of the organization’s ongoing and proposed projects. Alternatively, multiple project inventories can be created representing project portfolios for different departments, programs, or businesses. Since project portfolio management can be conducted at any level, the choice of one portfolio versus many depends on the size of the organization, its structure, and the nature and interrelationships among the projects that are being conducted.

Organization

There are three main organizational components to EPG: executive leadership, the portfolio management team, and program and project managers. Effective EPG requires that the individuals who direct and oversee governance activities be organized, and their contributions should be modeled to ensure that authority and decision making have a clear source, that the oversight is efficient, and that the needs for direction and decisions are addressed. Much of EPG may be carried out by multiple committees working at different levels. The committees or work teams used depend on organizational structures and culture, so not all organizations employ these committees at the same time. Thus, EPG is a collaborative process requiring a healthy mix of corporate, business units, and technical support services.

Stakeholder Management

Everyone has expectations that determine their behavior. Expectations are visions of a future state, often not formally manifested, but which are critical to success. Expectation management is crucial in all settings where people must collaborate to achieve a shared result, and EPG is no exception.

Performance Evaluation

For EPG to be effective, overall performance has to be measured and monitored on a periodic basis to ensure that it contributes to the business objectives while at the same time remaining responsive to the changing environment. Performance is typically evaluated during execution of an implementation plan, yet due attention is required for ongoing monitoring as well.

Business Transformation

Vision and strategy require adaptation and refinement to adjust to changing economic influences. Business agility, or the ability to achieve business transformation, is a measure of both management and corporate success and, as such, essential in pursuing the implementation EPG. Establishing change capability enables clients to continue optimizing performance in response to changing service demands and new strategic drivers

The relationship between the EPG factors and other organizational components is shown in Figure 27-2.

FIGURE 27-2. THE BIG PICTURE: HOW EPG RELATES TO OTHER ORGANIZATIONAL COMPONENTS

THREE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES

Board-Sponsored Enterprise Project Governance

In this scenario, corporate governance creates specific committees related to EPG, with names like strategic planning and implementation, operations oversight, product development, or events and programs. These committees can influence EPG policies as well as maintain oversight rights. As examples of organizations with corporate governance committees having scopes that relate to governance of projects, the Global Fund (a major organization aimed at fighting AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria) has a portfolio and implementation committee, and L’Oreal, the French cosmetics conglomerate, has a strategy and implementation committee.

How might these board-level committees help shape EPG policies? Although overall executive responsibility for implementing projects resides with the CEO and management team, a board-level committee can exert influence on the selection and implementation of strategic projects—those that will ultimately affect the company’s future. Here are actions appropriate for board-level committees that propose to focus on issues such as planning, strategy, and implementation:

• Require policies for selecting and prioritizing strategic projects.

• Require the organization to addresses issues of EPG, including project portfolio management.

• Set up a policy for oversight review of a few key initiatives (but avoiding micromanagement).

• Establish appropriate communication channels.

• Require periodic project management maturity assessments.

A CEO-Sponsored EPG

This governance structure is similar in concept to the first scenario except that the board delegates full responsibility to the CEO.

The common practice among many boards is to concentrate only on broad issues related to business ethics, risks, auditing, CEO succession, and internal board administration. All other responsibilities are handled by the permanent executive staff under the leadership of the CEO and executive team. Enterprise project governance takes place fully within the scope of the company’s full-time professional leadership. Policies, structures, and procedures for EPG are therefore developed under the umbrella of the CEO and C-level colleagues, and delegated to appropriate levels within the organization.

Enterprise project governance, then, is just one of several responsibilities of the CEO, who is charged with making projects and everything else work effectively. The board’s role regarding EPG is limited to hiring and firing the CEO, who, it is hoped, will be enlightened with respect to project governance policies. This limited EPG scope for board committees is prevalent in the corporate world and is adopted in organizations such as General Electric, Accenture, Roche, and Volkswagen. Enterprise project governance, then, is a matter to be organized and structured by the CEO and the executive team.

Where corporate governance has delegated full responsibility to the CEO to deal with all management and organizational matters, including strategies and projects, it falls on the CEO to provide for interface between the strategists (upper management and business planners) and the implementers (program and project managers). The following subsections discuss some of the ways the CEO can effectively deal with the project-related issues across the organization

The Chief Project Officer

In large organizations, the challenge of effectively coordinating hundreds of complex projects can be too much for a conventional hierarchical organization to handle. A solution to this is to designate a project-wise C-level executive to help coordinate the governance and oversight of multiple projects and major programs. This executive, called the chief project officer (CPO), shoulders the overall responsibility for EPG in the organization. Other titles, like VP for Special Projects or Head of Program Management, are also used to describe the same function. How a CPO operates depends on the maturity level of the organization with respect to project management (methodologies, past experience, and support), and the size and complexity of the projects. It also depends on the conviction of top management with regard to using an enterprise project approach to managing, and the nature of the organization—whether it is project-driven, like an engineering company, or functionally based, like a manufacturer of toothpaste that uses project management as a means to an end.

The CPO function makes particular sense in organizations that are global, multidisciplined, and require timely delivery of multiple, complex projects. A CPO’s responsibility is to care for the organization’s portfolio of projects—from the business case to final implementation, which includes the following tasks:

• Involvement in the business decisions that result in new projects

• Strategic project planning

• Setting priorities and negotiating resources for projects

• Oversight of strategic project implementation

• Oversight of an enterprise-wide project management system

• Development of project-management awareness and capability throughout the organization

• Periodic project review, including decision to discontinue projects

• Top-level stakeholder management, facilitation and mentoring

The Corporate Project Management Office

The corporate project management office (CPMO) is a small, strategic group, sometimes called the strategic project office. The CPMO is the link between the executive vision and the project-related work of the organization. Its functions include overseeing strategic items such as project management maturity, project culture, enterprise-wide systems integration, managing quality and resources across projects and portfolios, and project portfolio management. The CPMO is responsible for the project portfolio management process, and ensures that the organization’s projects are linked to corporate strategies. The CPMO ensures that the organization’s project portfolio continues to meet the needs of the business, even as these needs continue to change over time. It serves as the critical link between business strategy and execution of tactical plans.

The Program Management Office and Committees

The program management office (abbreviated PgMO to distinguish from the project management office, PMO), operates at a less strategic level than the CPMO and is designed to provide coordination and alignment for projects that are interrelated under the umbrella of a given program. An alternative approach for dealing with EPG issues involves the use of committees to provide the strategic guidance and oversight coverage for project management endeavors, for examples, the committee for strategic projects, the strategic steering committee, and the portfolio review committee. These committees have authority for prioritizing projects that cut across functional departments and are composed of executives from throughout the organization to ensure consensus and balance.

The CEO thus has multiple options for providing strategic guidance for managing projects across the enterprise. Which approach is the best fit and how the organization will be structured depend on the existing company culture, the developing needs within the organization, and the opinions of the principal decision makers.

Distributed Responsibility

In scenario 3, corporate governance provides no committee coverage for EPG, and the organization under the CEO establishes no formal structure such as a CPO or CPMO to deal with issues of portfolios, programs, and projects. Here, the challenge of dealing with multiple projects persists, yet the responsibility is scattered throughout the organization.

In this setting, a growing awareness exists at the middle management and professional levels regarding the need for a coherent enterprise-wide set of policies, competencies, and methodologies for managing projects of all natures and types. At this hands-on level, benefits for an EPG-type approach is evident to participating stakeholders, because this holistic view implies that the organization will be supported with appropriate systems, trained personnel, and an overall project culture.

The awareness, however, is not as evident to upper management. Proposals to top decision makers for an overarching program like EPG fall on deaf ears. This leaves the interested parties with two options. The first is to “go with the flow” and keep plugging away as best as possible and hope that something will sway opinions in the future. The other option is to take a proactive stance and embark on a policy of advocacy for the EPG cause. This implies using techniques of influence management to create interest and awareness. Here are some effective approaches:

• Target potential champions that might help carry the flag for the EPG cause.

• Distribute published literature, including magazines and Internet publications, that documents how competitors or other organizations take project management to a higher levels.

• Use indirect influencing by involving people who have access to the ears of the decision makers.

• Prepare a business case showing feasibility and proposing a step-by-step approach.

Such a bottom-up approach may be articulated by existing PMOs because they surely have awareness and interest in articulating such a movement.

IMPLEMENTING ENTERPRISE PROJECT GOVERNANCE

How to proceed depends on factors such as the actual need, the existing culture, the presence of a champion, and a feasible plan for making the implementation. Initiative for promoting the EPG concept may start at different levels, such as the board, CEO and executive team, middle management, or the “bottom-up” approach. Here are a few suggestions.

A Simplified Incremental Approach

Formal EPG is in reality an evolutionary approach. Like other project management improvement initiatives have done in the past, EPG can be introduced and upgraded incrementally. If there is minimal awareness in the organization about the impact project management has on organizational results, lack of a project management culture, insufficient sponsorship to champion the cause, or a lack of expertise in change management, partial initiatives may be appropriate. Here are some starting points:

• Intensify training programs in project management basics.

• Stimulate use of project management techniques across the enterprise in all types of projects, including engineering, IT, research and development (R&D), new product development, marketing, and human resources.

• Create awareness at the executive level through literature, benchmarking, and conferences.

• Identify potential sponsors for a broader program.

• Stimulate implementation and development of PMOs.

With these measures in place, an organization will be on its way to producing highly successful projects of all types across the enterprise. That said, a comprehensive EPG program offers the best way to guarantee optimal project performance and boost overall organization results.

Enterprise Project Governance Roadmap

The elaboration of an EPG plan may ultimately develop into a manual for maintaining the concept in place. Such a manual becomes a repository for definitions, approaches, processes, and lessons learned from execution, becoming an organizational asset. As time goes on, the document will be subject to adaptation, review, change, and improvement, creating an organizational learning cycle. There are nine factors to be considered in the EPG plan:

Stakeholder Size Up

The principal stakeholders fall into the organization’s main publics of interest. These publics of interest may be internal “champions” or the organization’s external publics. The champions have the power to initiate projects and shape their ultimate impact on the organization. In generic terms, the champions include board and project committee participants, project sponsors, and upper management overseers. On the other hand, there is a growing concern about the impacts that projects may have on certain communities and the power they may have to paralyze organizational projects. External publics include investors, clients, consumers, suppliers, and regulatory agencies.

Context and Culture

To understand the internal and external business context and current culture in which the organization operates, scenario and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis from the corporate strategic plan must be translated into assumptions. Project competency gaps identified by human resources must be addressed. Organizational climate and attitudes toward projects and compliance and the characteristics of the culture that may impact the EPG framework must be analyzed.

Strategy Alignment

Enterprise project governance needs to clearly align organizational mission, vision, values, and strategic intentions as stated into the corporation’s strategic plan to all the programs and projects in the organization. For mandatory projects, the decision is not whether to undertake the project but how to oversee them in order to guarantee all the compliances required. For successful program and project selection, attention is focused on alignment with strategic objectives and the “go/no-go” decision with respect to best value. All the projects must individually consider not only the deliverables but also the organizational benefits resulting from the deliverables’ implementation.

Directing

Promote and motivate expected behaviors by organizing the policies, methodologies, standards, and guidelines applicable to EPG. In addition, all the systems related to project implementation must be clearly defined and an effort made to standardize them instead of having a software Tower of Babel. Finally, develop a glossary because standardizing project language is key to EPG.

Risk Management

Managing risk in an integrated way allows effective responses to rapid changes in the organizational environment, natural disasters, and political instability. For such, a link between EPG and the organizational risk management approach is required pinpointing the critical organizational risks, and outlining how the approach to portfolio, programs, and projects are integrated with the overall risk approach to the organization. It is also important to link EPG to how the organization responds to business disruption, crisis, and recovery.

Portfolio Management

A single project inventory can be constructed containing all of the organization’s ongoing and proposed projects. Since project portfolio management can be conducted at any level, the choice of one portfolio versus many depends on the size of the organization, its structure, and the nature and interrelationships among the projects that are being conducted. Enterprise project governance must describe the following:

• Portfolio proposals: how to select projects and programs that represent the best value to the firm and that are aligned with strategy

• Portfolio processes: how the portfolio will be managed

• Portfolio integration: integration processes (for companies with portfolios across business units or geographical areas)

Structure, Roles, and Responsibilities

To be effective, the individuals who direct and those who oversee governance activities must be integrated, and their contributions modeled to ensure that authority and decision making have a clear source, the work of management and oversight is efficient, and the needs for direction and decisions are addressed. The EPG plan should therefore define the following:

• Goals and expected outcomes of the EPG system: its scope, what it will achieve, and how it relates to business objectives.

• Key roles and accountabilities.

• Board roles and accountabilities: the board has oversight of the system and ultimately is the active monitor for shareholder and stakeholder benefit. The board must:

• Address long-term issues.

• Direct the purpose and desired outcomes of the organization.

• Set a charter for its involvement.

• Set business objectives and ensure they are congruent with values and risks.

• Obtain regular assurance that the system is effective.

• Committees roles and accountabilities: most EPG work is carried out by committees, and in many organizations multiple committees work at different levels. The actual committees depend on the organization size, culture, and leadership style.

• The Role of Management:

• Design, implement, and operate an effective EPG system.

• Provide regular assurance about the effectiveness of the system.

• Communicate with key stakeholders about issues arising.

• Evaluate and optimize the performance of the system.

• The role of assurance: management should obtain and provide regular assurance about the effectiveness and performance of the EPG system. An independent expert can reveal weaknesses in design or operation, and define opportunities for integration and exchange of best practices. Internal or external independent reviews can be used. Those providing assurance, whether internal or external, should:

• Provide assurance that risks are appropriately identified, evaluated, managed, and monitored.

• Provide regular assurance to the board and management of the effectiveness of the EPG system in light of the organization’s culture and objectives.

• Decision-making processes: a set of processes must be established as authoritative and within which portfolios, programs, and projects are initiated, planned, and executed, to ensure that goals and benefits are met:

• Project identification: describe the processes for proposing a program or a project, including if it is a mandatory one or aligned with business objectives.

• Project selection: describe how projects and programs are selected and how to decide on go/no-go.

• Why–how framework: describe how to develop a why–how framework for each project or program.

• Project start-up: describe how to initiate a project or a program.

• Project reviews: describe the approach for programs and project reviews.

• Risk processes: describe the best practices to be applied for the program.

• Portfolio processes: describe the processes chosen to deal with handling the management of portfolios.

This roadmap provides a guideline for embarking on a program of enterprise project management. It serves as a basis for developing a customized plan for addressing the specific issues and desires of any given organization. Some of the requirements may already be in place, whereas others may require major planning and implementation effort.

Performance

Performance analysis of the EPG initiative must include a maturity analysis of how projects are contributing to the achievement of the organizational ambition, how success can be replicated, and how the organization is learning from the initiative. The result of this performance analysis must be an action program driving improvement.

Transformation

The implementation of an EPG effort and the resulting desired change affects people and as such must be planned. People need to be informed, and their actions and reactions evaluated. Organizational change management will be required.

CHALLENGES AND ROADBLOCKS IN IMPLEMENTING ENTERPRISE PROJECT GOVERNANCE

As in any other endeavor involving change in an organization, well-developed plans can pave the roadway for smooth motoring toward desired goals. Here are ways to prevent problems along the route to EPG:

• Show what the competition is doing with regard to project management.

• Demonstrate studies from professional associations, such as the Project Management Institute (PMI) and International Project Management Association (IPMA), regarding the impact of an organizational approach to project management.

• Benchmark with other companies with known expertise in high-level project management.

• Do a risk analysis of the implementation project, including factors such as probable challenges, likelihood of occurrence, and stakeholder influences.

Despite a well-planned rollout of an EPG project, unexpected challenges may appear along the way. Corrective approaches to unexpected barriers include the following:

• Put the program temporarily on pause. Sometimes time itself will sort out an issue.

• Reevaluate the situation. What has changed? What new factors have come into play?

• Replan. If a plausible plan B is on standby, then put it into play. If not, then develop a modified plan.

ERICSSON: A CASE OF ENTERPRISE PROJECT GOVERNANCE EVOLUTION

In practice, many organizations evolve over time toward a broad enterprise approach for managing projects. Such is the case of Ericsson, a global telecommunications manufacturer headquartered in Sweden, which spent decades developing project management expertise. Known as PROPS (for PROject for Project Steering), the framework’s objective is to enable project managers anywhere in the world to complete their projects successfully. In the late 1980s, the company developed the first PROPS version to support the development of digital telecom switches. The introduction of mobile telecom networks sparked the need to develop a more generic model that was uncoupled from specific product lines. Later, generic versions were developed with focuses on (1) customer projects, (2) market-based R&D, and (3) internal company projects. This broadened the focus to general project management practices and encompassed the business context of projects.

Ultimately, this led to the company’s projectization, where projects became the way of working at Ericsson, because as much as 80 percent of the company’s employees work on projects. The PROPS framework has gone through multiple versions and has become a framework for enterprise project management aimed at all project-related areas, including project management, program management, portfolio management, and project offices. Focus is on the enterprise as a whole and multiple projects of sundry natures. The key points of the PROPS framework are as follows:

• Business perspective

• Human perspective

• Project life-cycle model

• Project organization model

In essence, the framework contains the basics for EPG, and is used as a basis for similar programs at Volvo, Saab, and other international companies.

The creation and evolution of PROPS was sponsored and supported by top management. A small unit responsible for project management support was given the assignment to host the framework and act as an internal consultancy team. A group of technical writers was brought in to ensure that PROPS was documented and launched in a way that would be reader friendly and attractive to potential users. Later, an internal center of excellence became responsible for development of PROPS, as well as for project management training and support. This focused group of people dedicated to PROPS cause was a key factor for its success.

Ericsson gradually developed a fully projectized culture from top to bottom, and did so by continuously upgrading its basic project management framework, with the full involvement and support of top managers. According to Ericsson’s Inger Bergman, “Changing a company from a traditional hierarchical, functional manufacturing industry to an agile player in the IT area is not easy and takes time and effort. Project management is now seen as an important asset for the company and a competitive advantage in R&D and sales delivery.” Ericsson is an example of the evolution of project governance capabilities.4

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This chapter is adapted and excerpted from Paul Dinsmore and Luiz Rocha, Enterprise Project Governance (New York: AMACOM, 2012), by permission of the publisher.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

![]() Where does project and/or portfolio governance reside in your company?

Where does project and/or portfolio governance reside in your company?

![]() Thinking of a recent project or program that was challenged, how might appropriate governance made a difference?

Thinking of a recent project or program that was challenged, how might appropriate governance made a difference?

REFERENCES

1 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, revised edition (Paris, France: OECD, 2004), http://www.oecd.org/daf/corporate/principles.

2 World Bank, “Corporate Governance: Improving Transparency and Accountability,” 2005. Quoted in “How Corporate Governance Affects the Strategy of Corporations: Lessons from Enron,” in Hameed Ahmed and Ali Najam, master’s thesis, Department of Management and Economics, Linköping University, Sweden, 2006, www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:21551/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

3 Association for Project Management (APM), Directing Change: A Guide to Governance of Project Management (High Wycombe, UK: Association for Project Management, 2004), www.apm.org.uk.

4 Paul C. Dinsmore and Terrance J. Cooke-Davies, Right Projects Done Right (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006), pp. 111–117 and 275–280.