CHAPTER SEVEN

ALIGNING BOARDS AND INVESTORS

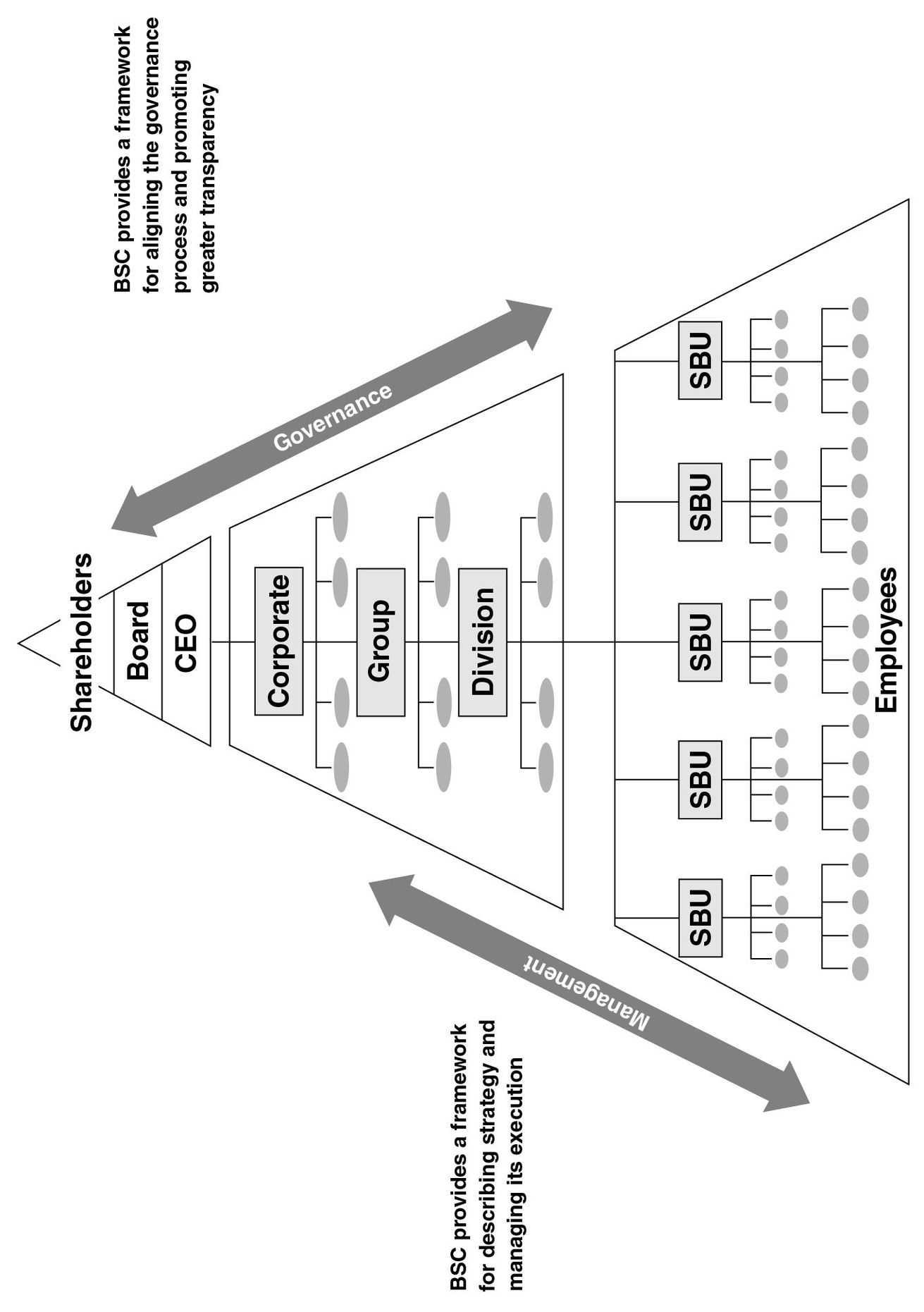

IN PREVIOUS CHAPTERS, we discussed how Balanced Scorecards help to align and create synergies across internal business and support units (see the arrow at the left in Figure 7-1). With the increased emphasis on corporate governance, executives are now creating additional corporate value by using the Balanced Scorecard to enhance governance processes and to improve communication with shareholders (see the arrow at the right in Figure 7-1). As Jeff Immelt, CEO of General Electric, stated, “I want investors to know that they can trust us to govern our Company effectively. Then, they can judge GE by the quality of our business, our strategy, and our execution.”1

Effective governance, disclosure, and communication reduce the risk that investors face when they entrust their capital to company managers. In this chapter, we show how companies can use the Balanced Scorecard to enhance their corporate governance and disclosure processes. Before illustrating this new application of the Balanced Scorecard, we introduce fundamental concepts in corporate governance.

GOVERNANCE 101

All market systems require intermediaries to help direct capital to its most productive opportunities and to monitor the performance of managers who have been granted capital by external investors.2 Not all business ideas proposed by managers and entrepreneurs are “good” ideas that deserve funding. In the absence of valid information about business opportunities, investors cannot sort the good ideas proposed by company managers from the bad ideas.

Figure 7-1 The Balanced Scorecard Helps Organizations Manage the Value Creation Process at Each Level

This problem of hidden information—in which sellers (company managers) have much better information about their investment opportunities than buyers (potential investors)—arises in other markets as well. Consider the market for used cars. Prospective buyers often cannot get valid information from the seller about the condition of the car, and they do not have access to independent information about its quality. In this situation, sellers have superior information about the quality of the product or service being offered (called the adverse selection problem by economists).

Consequently, the used car buyer rationally assumes that the car is in bad condition and offers a price based on having to pay the cost to repair a lemon. Potential sellers of used cars that have been maintained in an excellent fashion will not be able to get full value for their vehicles and hence will not offer their cars for sale in such a market. The result is a poorly functioning market in which only low-quality products and services are offered for sale.

Extending this example to the capital market setting, if managers cannot credibly communicate the underlying value of their proposed projects, investors will not be willing to provide funds at a price that managers with excellent projects find attractive.3 Thus, many high-return investment opportunities will not get funded.

Capital markets must also monitor how managers use the money that investors have provided them. Managers and investors do not have identical interests. Managers may make investments that increase the size of the company but not its profitability. Or, rather than pay dividends when good investments are not available, managers may retain cash to shield themselves from the discipline of justifying investments for future new projects.

Managers also can consume some portion of “other people’s money” by occupying plush office space, operating a fleet of corporate jets, and taking excessive compensation. Managers may also distort the financial statements and disclosures they make to their investors to portray a better picture of company health than the economic reality warrants. Such distortion generates higher bonuses and helps them avoid the potential loss of their jobs if the true picture of their underperformance were revealed. These are all examples of managers’ hidden actions, or moral hazard—when managers act according to their self-interest rather than in the interest of the company’s owners.

Dispersed investors find it costly to monitor and sanction the disclosures and decisions taken by managers, especially when the managers’ actions are not fully disclosed to them. If the consequences of managers’ hidden actions cannot be mitigated, then investors will be reluctant to put their capital at risk by investing in corporations.

Advanced market economies have evolved a variety of institutions to mitigate such adverse selection and moral hazard problems in capital markets. Economies that are better at mitigating these problems grow faster and produce higher standards of living for their citizens than those that cannot attract and allocate private capital to attractive domestic investment opportunities.

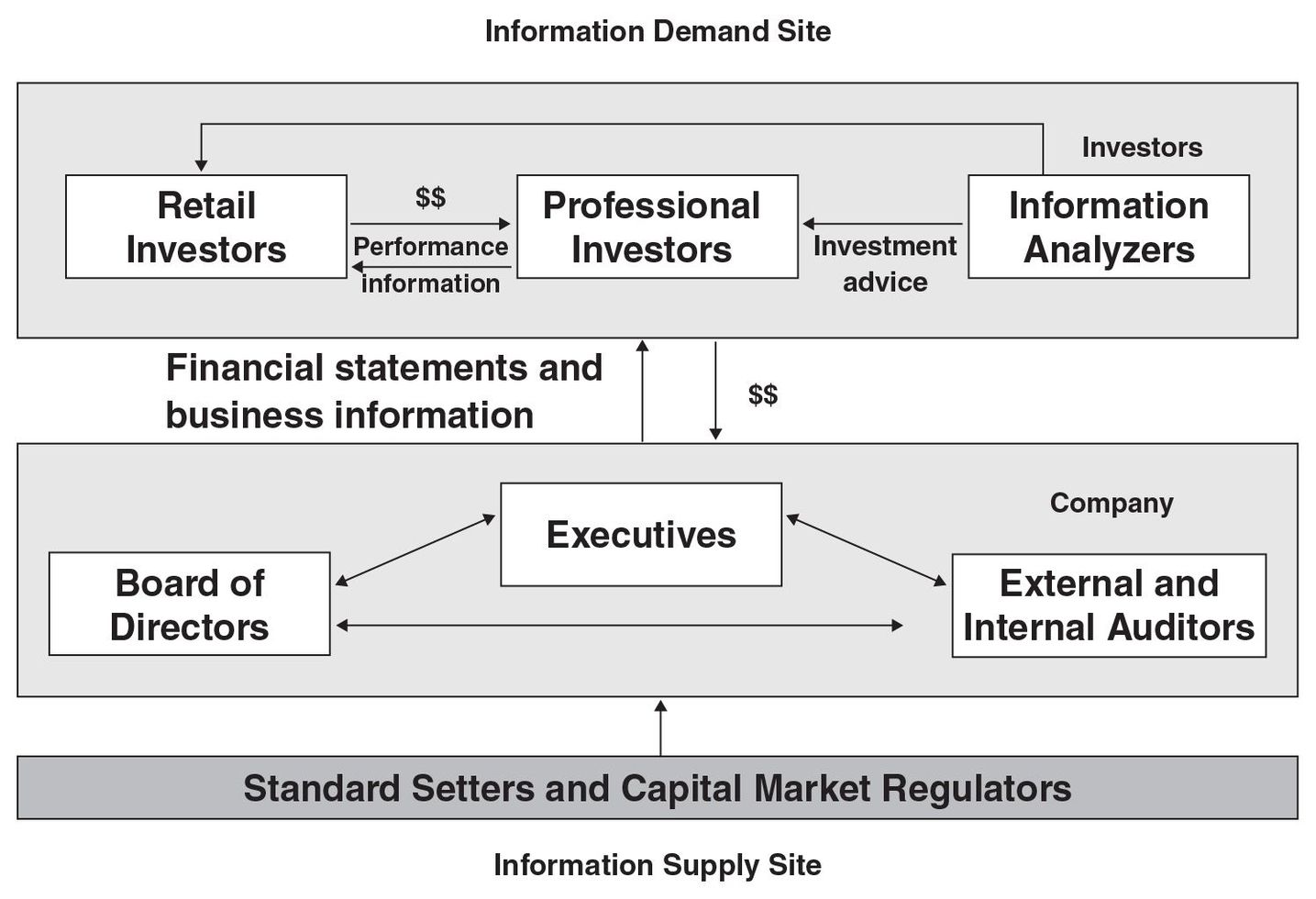

Among the institutions that play a role are information and capital market intermediaries, such as analysts and professional money managers (see the top row in Figure 7-2). Analysts interpret companies’ financial statements and disclosures, analyze companies’ prospects, and make recommendations about which companies represent attractive or unattractive investment opportunities. Professional money managers—including mutual funds, venture capital investors, and private equity investors—pool savings from diverse retail and institutional clients and, based on their own financial and business analysis and that of external analysts, provide capital to the most attractive investment opportunities.

Figure 7-2 Capital Market Intermediation Chain

The analysis, interpretation, and actual investing decisions made by retail investors and their professional managers are informed by the financial statements and disclosures prepared by company managers. To ensure that these financial statements and disclosures are reasonably representative of the operations of the companies, external auditors examine and test the validity of the reports, thereby mitigating the moral hazard problem that arises when managers report on their own performance.

Perhaps the most important component of this entire system of intermediation and governance is a company’s board of directors. An active and engaged board is an essential part of shaping and executing a successful strategy. Boards contribute to organizational performance when they fulfill the following five major responsibilities:

- Ensure that processes are in place for maintaining the integrity of the company, including

- Integrity of financial statements

- Integrity of compliance with law and ethics

- Integrity of relationships with customers and suppliers

- Integrity of relationships with other stakeholders.

- Approve and monitor the enterprise’s strategy.

- Approve major financial decisions.

- Select the chief executive officer, evaluate the CEO and senior executive team, and ensure that executive succession plans are in place.

- Provide counsel and support to the CEO.

We elaborate on these five responsibilities next.

Ensure Integrity and Compliance

Directors must ensure that corporate reporting and disclosure represent the underlying economics of company performance and its key risk factors. Integrity and compliance in financial reporting include conforming with legal, accounting, and regulatory requirements, such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 in the United States. Internal and external auditors help a board gain assurance that the company’s reporting, disclosure, and risk-management processes comply with these rules and regulations.

Directors must also monitor the risk taken by the company and must verify that managers have installed adequate risk-management processes to mitigate the adverse consequences should unanticipated events occur. The board must ensure that the company has adequate systems of internal controls to prevent loss of the company’s assets, information, and reputation. And it must ensure that company managers are operating ethically, within the company’s code of conduct, in the company’s dealings with suppliers, customers, and communities as well as with employees. The board verifies that employees have not violated laws and regulations that would risk the company’s assets and even its right to operate.

Approve and Monitor Enterprise Strategy

Board members do not generally participate in the creation and formulation of strategy. This is the responsibility of the CEO and the executive leadership team. But board members ensure that the company’s leaders have formulated and are implementing a strategy for long-term creation of value for shareholders. And board members approve or reject major management decisions related to implementing the strategy.

To carry out this responsibility, board members must fully understand and approve the company’s strategy. Once the strategy is approved, directors continually monitor its execution and results. For these purposes, directors must know the key value and risk drivers of the business.

Approve Major Financial Decisions

The board ensures that financial resources are being used effectively and efficiently to achieve strategic objectives. The board approves the annual operating and capital budgets and authorizes large capital expenditures, new financing or repayments, and major acquisitions, mergers, and divestitures.

Select and Evaluate Executives

Directors hire the chief executive officer and determine his or her compensation. The board also generally approves the hiring of other members of the senior executive team. Annually, the board assesses the performance of the CEO and the executive team and approves appropriate compensation and incentives.

To protect the company from the unexpected death, illness, injury, or voluntary departure of any key executive, the board must ensure that a succession plan exists for all members of the executive team.

Counsel and Support the CEO

The board counsels and advises the CEO. Individual board members use their specific knowledge of the industry and their functional and management expertise to provide guidance based on the company’s history and competitive positioning. Directors share their knowledge, experience, and wisdom as the executive team describes strategic opportunities and impending major decisions.

LIMITED TIME, LIMITED KNOWLEDGE

To carry out their multiple responsibilities, board members need to know a great deal. They must know about financial results, the company’s competitive position, its customers, its new products, its technologies, and its employees’ capabilities. They must be aware of the performance and capabilities of the top managers as well as the broader talent pool.

And boards must know whether the company is complying with legal, regulatory, and ethical standards.5

Edward Lawler is a scholar of human capital, organizational effectiveness, and, more recently, corporate boards.4 He writes, “A board should be focused on lead indicators. The challenge is to know what the right lead indicators are—which ones are unique to the organization and its business model . . . Boards need to review information about the culture of the organization. They need indicators of how customers and employees feel they’re being treated.”6

Boards often fall short in carrying out their responsibilities because of the limited time they have available and the inadequate information provided to them. The boards of failed companies, such as Enron, World-Com, and Adelphia, did not have adequate information to understand what was transpiring.7 Some 90 percent of directors are not members of the executive team; they are part-time, outside directors. Many companies now consider an outside director as “not independent” if the director’s company represents more than 1 percent of the company’s financing, supplies, or sales.

As a consequence, “independent” directors now have far less specific knowledge of the company and its industry. Although such “independence” may offer some protection to investors, it limits the depth of knowledge independent directors can acquire and maintain about the company’s industry and competitive position, especially if most of the information they receive consists of quarterly and annual financial statements.

Outside and independent board members also usually hold significant leadership positions in their own organizations. They find it difficult to dramatically increase the amount of time they can spend on board matters. Companies must find ways to use board members’ available time more effectively. Such effective time management includes streamlining the information board members receive and evaluate before meetings and the information presented during meetings. It also includes focusing board meetings on matters that are of the highest strategic importance for the company. As a leading board scholar, Jay Lorsch indicates, “If directors were regularly getting a Balanced Scorecard, they would be much more likely to be informed about their companies on an ongoing basis. The scorecard’s emphasis on strategy (linking to all activities, day-to-day and long-term) could help directors stay focused.”8

A governance system built on the Balanced Scorecard helps the board of directors meet the two critical board challenges of limited time and limited information.

USING THE BALANCED SCORECARD IN BOARD GOVERNANCE

The use of the Balanced Scorecard by boards of directors is an emerging new application, although one that we feel will increase over time. An increasing number of companies are including Balanced Scorecards in the board packet and are reserving time for their discussion during board meetings.

First Commonwealth Financial Corporation, a regional bank holding company based in central and western Pennsylvania, has been a leader in making the Balanced Scorecard the central document for board review and deliberations. In the next sections, we draw heavily upon the First Commonwealth experience.9

The Enterprise Scorecard

A board’s Balanced Scorecard program starts with approving the organization’s Strategy Map of linked strategic objectives and the associated enterprise Balanced Scorecard of performance measures, targets, and initiatives. This enterprise scorecard, of course, would have been created primarily for its traditional role of helping the CEO communicate and implement the corporate strategy throughout the organization.

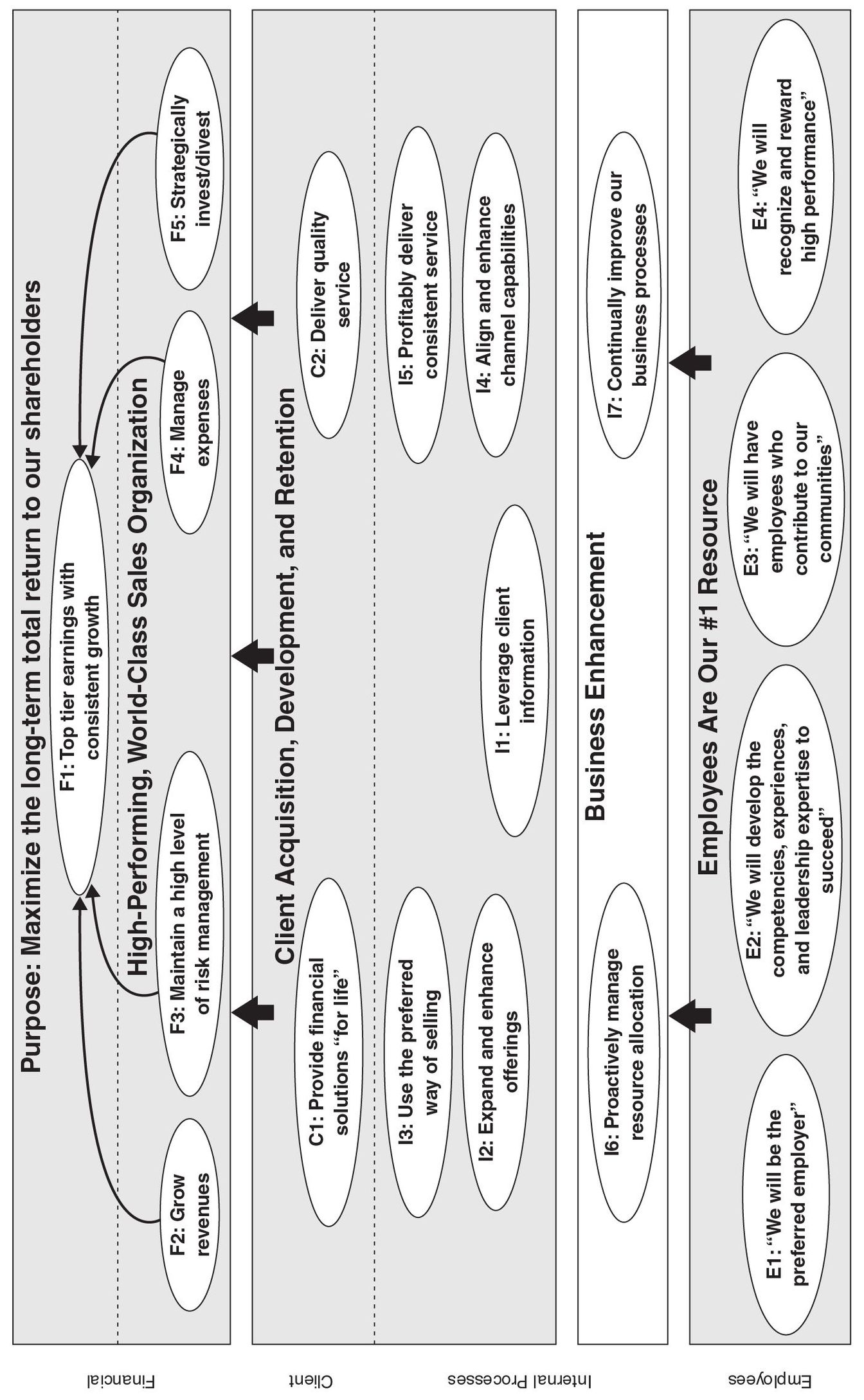

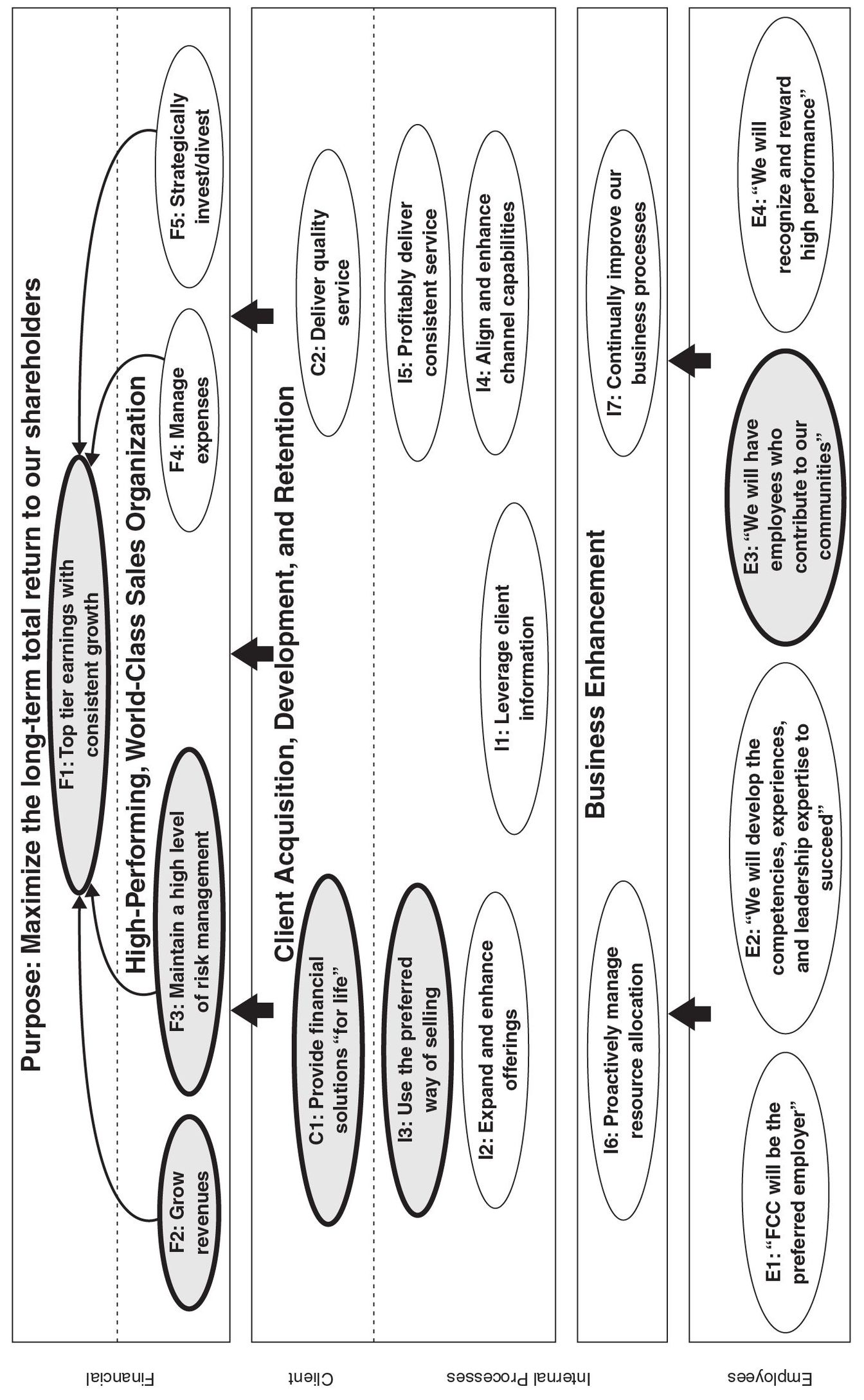

For example, consider the Strategy Map in Figure 7-3 for First Commonwealth Financial Corporation, which adopted the Balanced Scorecard to implement a new strategy focused on lifetime customer relationships. The Strategy Map clearly portrays the high-level financial objectives of revenue growth and productivity enhancements; the customer objectives of lifetime relationships and excellent service delivery; the critical internal processes of leveraging client information and selling bundled financial products and services tailored to individual customer needs; and the learning and growth objectives of motivating and training employees in the new strategy and new way of selling. The Strategy Map has an accompanying Balanced Scorecard of measures, targets, and initiatives.

CEOs can use the enterprise scorecard for interactive discussions with their boards about strategic direction and performance in strategy execution. Used in this way, the Balanced Scorecard plays a central role in governance by providing board members with essential financial and nonfinancial information to support their responsibilities for overseeing performance.

For example, Wendy’s International, one of the world’s largest restaurant operating and franchising companies with more than 9,500 total systemwide restaurants, uses its BSC to communicate with its board of directors. The board does an intensive annual review of the financial results, process redesign benefits, new store growth, market share, customer satisfaction, taste and value-for-money comparisons against key competitors, and employee satisfaction and turnover. The board is updated quarterly on specific leading indicators, especially consumer-attributes feedback and market share changes.10

Initially, the executive team brings its enterprise Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard to the board for review and approval. Ideally, the review should be done before these documents have been finalized, so that board members can contribute to discussions about strategic direction and positioning. The Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard are the single most succinct and clear representations of the organization’s strategy. They enable the board to understand the strategy, and they provide the basis for the board’s evaluation of whether the strategy is capable of delivering long-term shareholder value at acceptable levels of business, financial, and technological risk.

Once approved by the board, the enterprise Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, with supporting documents of the scorecards of the primary business and support units, become the primary documents distributed to the board in advance of meetings. For example, at First Commonwealth Financial, the first page of the board package is a colorcoded Strategy Map indicating those strategic objectives that are performing ahead of plan, at plan, and those that are falling significantly short of plan. These results become the agenda for board meetings, as the CEO engages directors in an interactive discussion about the company’s recent experiences in implementing the strategy. Through a process of continual reforecasting, board members are kept informed of management’s expectations for future performance of key financial measures and the company’s key value drivers. Members of the audit committee become familiar with the risk factors underlying the company’s operations and strategy, and this awareness helps to guide their decisions on financial reporting and disclosure.

Figure 7-3 The First Commenwealth Financial Corporation Entreprise Strategy Map

Executive Scorecards

The second component of a board Balanced Scorecard program consists of executive scorecards that the full board and the compensation committee can use to select, evaluate, and reward senior executives. Executive compensation has been identified as an area where board performance has been most inadequate.11 Many observers of board processes now believe that board compensation committees fail to set executive compensation at levels appropriate to their responsibilities and performance. These observers argue that board compensation committees have been captured by CEOs and the compensation consultants hired by CEOs to “assist” the board in setting executive compensation levels.

Clearly, for boards to perform their responsibilities for executive oversight and evaluation, they need a tool to provide them with a valid, objective assessment of executive performance. The board should design and approve a compensation and incentive system that rewards executives when they create short- and long-term value. The compensation plan should produce below-average compensation when executive performance falls short of industry averages.

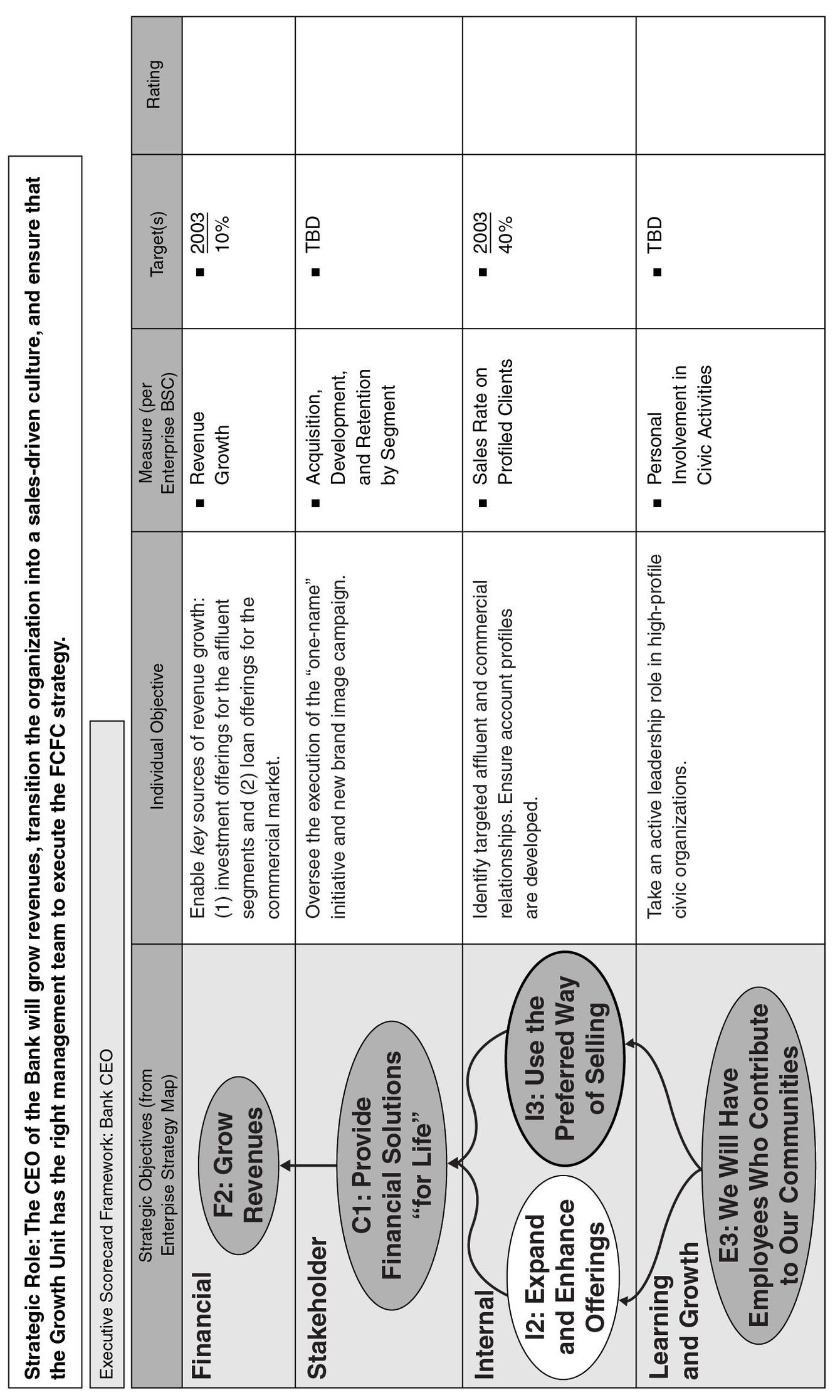

Executive scorecards describe the strategic contributions of key executives. They help the CEO and the board to isolate the performance expectations of an individual executive from the performance expectations of the entire enterprise. The process of developing an executive scorecard starts with the enterprise scorecard. The CEO and the executive team come to an agreement about those enterprise objectives that are the primary responsibility of each member of the executive team.

For example, the chief information officer will likely have responsibility and accountability for objectives relating to information technology capabilities in the learning and growth perspectives, and also for the internal and customer objectives whose success is driven by excellent databases and information systems. The chief human resources officer will have primary responsibility and accountability for ensuring that employees have the requisite skills and experience to execute the strategy, that an effective communication process has made all employees aware of the enterprise and business unit strategy, and that each employee has personal objectives, a personal development plan, and an incentive plan based on contributing to the strategic objectives of the business and the enterprise.

In the case of First Commonwealth, Figure 7-4 shows the highlighted Strategy Map objectives for the CEO of the bank, and Figure 7-5 shows the associated executive scorecard with representative measures and targets for the bank CEO. Notice that the bank CEO has primary responsibility for the new marketing and sales strategy, but that other executives—the COO and the CIO—have primary responsibility for the cost, quality, and responsiveness of daily operations. The bank CEO also is expected to play the leadership role in establishing First Commonwealth’s visibility and contributions in every community in which it operates.

By developing executive scorecards for each member of the senior leadership team, the CEO aligns the executive team with the strategy and gains an explicit mechanism for holding them accountable for their performance and contributions. The CEO can then reward them based on objective measures of their performance. Executive scorecards provide the board’s compensation committee with information it can use to assess how well the CEO is evaluating and rewarding individual executive performance.

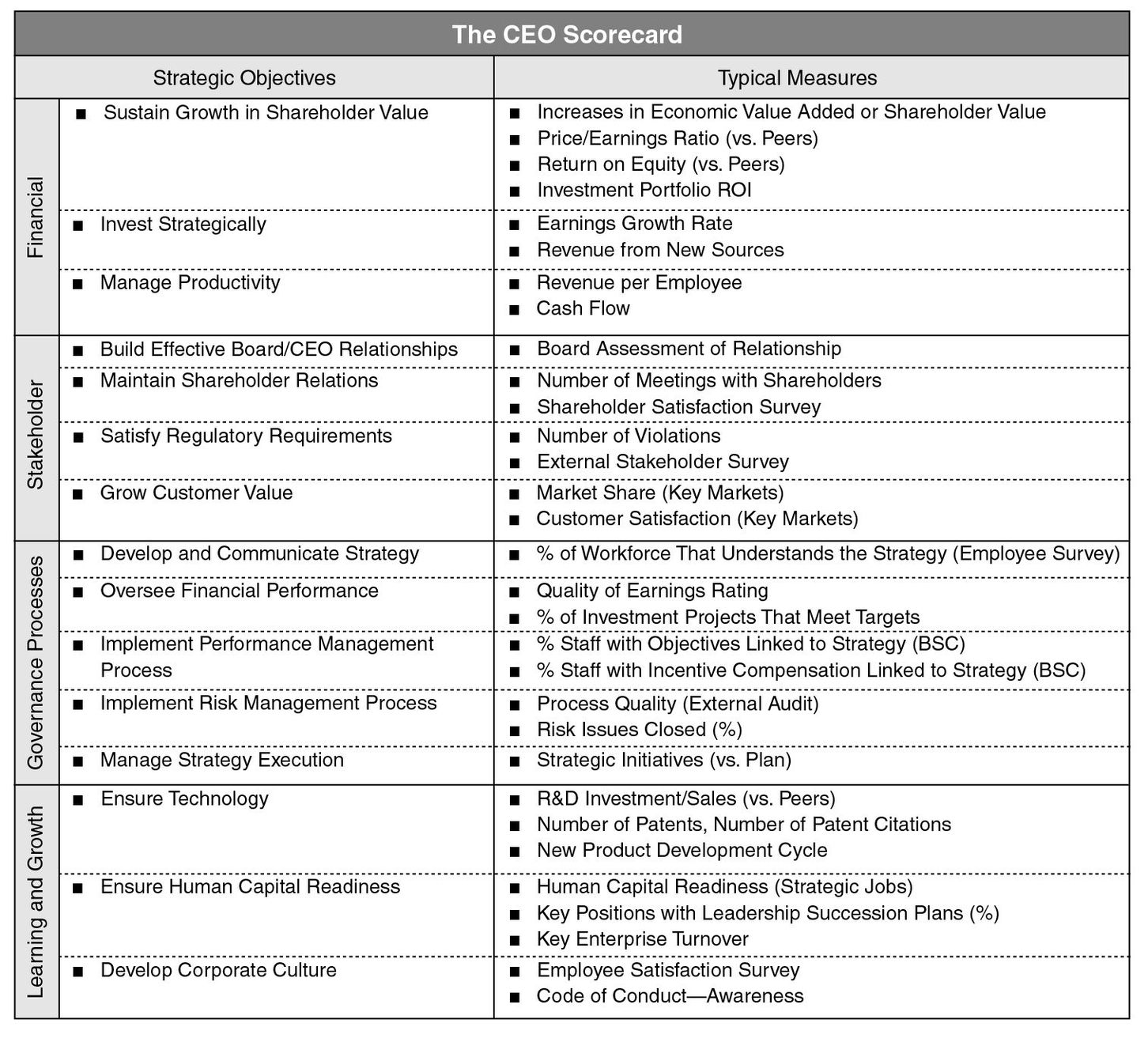

The CEO scorecard can be derived in the same way, highlighting those aspects of the enterprise scorecard that he or she has the primary responsibility for implementing. The CEO scorecard, and perhaps that of other senior executives, can be supplemented by key performance indicators that relate to the CEO or other senior executive roles beyond successful strategy implementation and increased shareholder value. For example, the CEO may have specific accountabilities for instituting effective governance processes, ensuring environmental and community performance, and maintaining relationships with key external constituencies such as investors, strategic customers and suppliers, regulators, and political leaders. Figure 7-6 shows a broader set of indicators that the board might draw on when establishing CEO and executive scorecards.

Figure 7-4 Executive Scorecard Identifies the Bank CEO’s Strategic Contribution

Figure 7-5 The Executive Scorecard Clarifies and Measures the Strategic Contribution

The board compensation committee should use the CEO’s executive scorecard when designing its performance contract, thereby providing an objective and defensible basis for the CEO’s compensation arrangement. Performance targets for the CEO’s scorecard measures can be established based on explicit growth targets and performance relative to the industry.

The governance committee can also use executive scorecards as strategic job descriptions that provide the basis for executive succession plans and for identifying succession candidates. Cohn and Khurana express concern about the typical process used by boards to select CEOs: “CEOs are often selected, compensated, and held in awe more for the charisma and confidence they exude in their pinstriped Brooks Brothers suits than for their actual skills and competencies . . . [O]ften boards are at a loss to evaluate the real skills, experiences, and competencies that an individual needs to lead a particular company in a particular environment.”12

Figure 7-6 Structure and Measures for Another Type of CEO Scorecard

When openings develop at the executive team level, the enterprise and executive Balanced Scorecards can help the board search for rising stars within the organization who have the experience and capabilities required for senior-level strategy implementation. The scorecards also provide guidance to the board in recommending specific training and job positions to high-achieving individuals so that they can become better prepared to assume senior-level leadership positions in the future.

When senior-level positions cannot be filled via internal promotions, the board’s search committee can use the Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard measures to create a position profile that will guide external searches, typically assisted by an executive search firm. Cohn and Khurana urge boards to use the quantified objectives on a Strategy Map to guide succession planning and execution: “[S]earch committees will stay focused on identifying and recruiting talent that meets their specific implementation challenges, and not succumb to the charisma of leaders who lack the relevant skills.”13

Board Scorecard

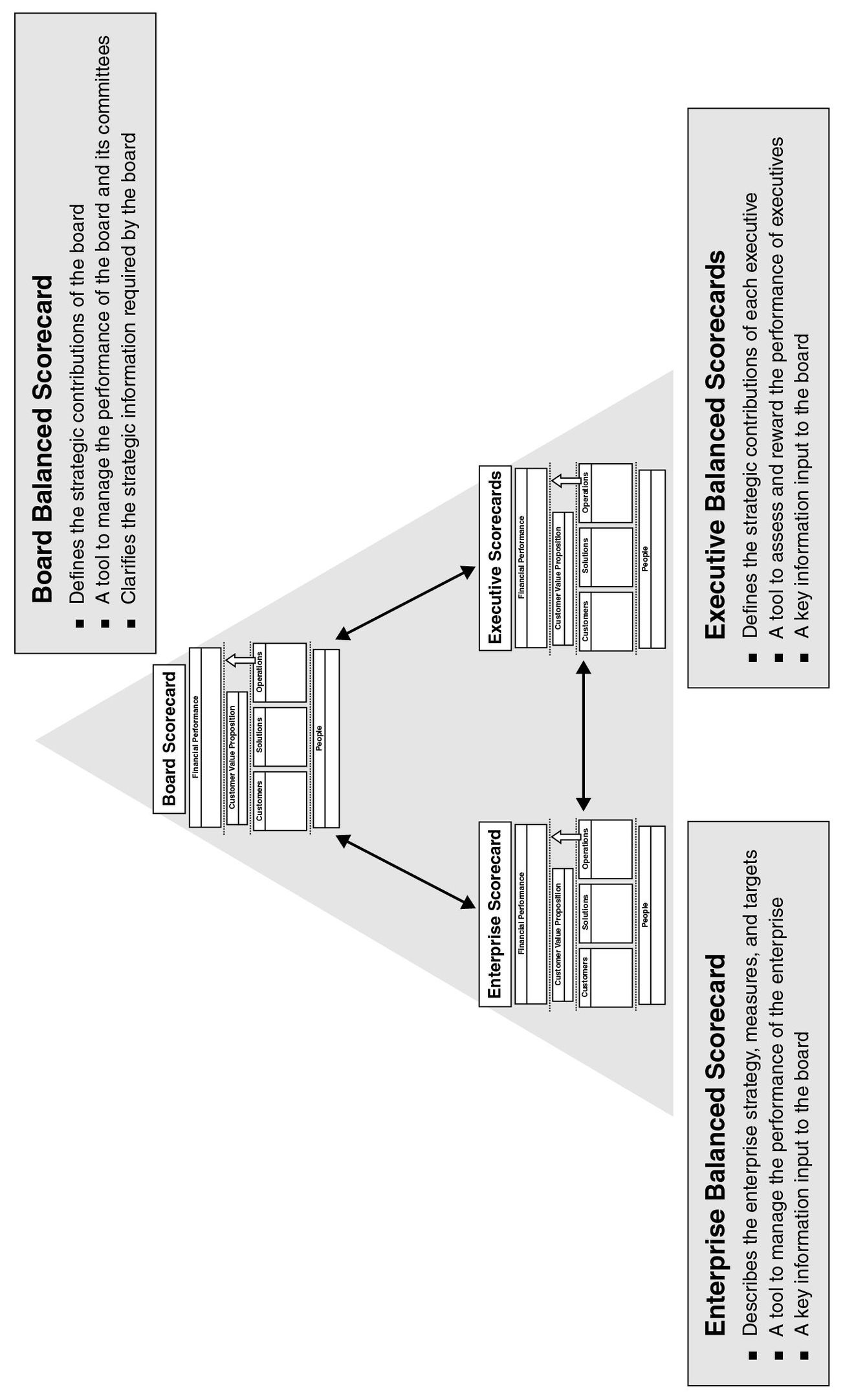

We believe that most boards will find using an enterprise Balanced Scorecard in their periodic meetings, and using Balanced Scorecards to monitor senior management performance, as straightforward applications of their responsibilities for strategic oversight. In fact, a leading Canadian accounting organization has advocated that this practice become standard for all companies.14

A novel application is to develop a Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard for the board itself. The U.S. Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires that boards make an annual assessment of their performance. What better tool for such a performance evaluation than an explicit statement of the board’s strategic objectives? A board Balanced Scorecard provides the following benefits:

- Defines the strategic contributions of the board

- Provides a tool to manage the composition and performance of the board and its committees

- Clarifies the strategic information required by the board

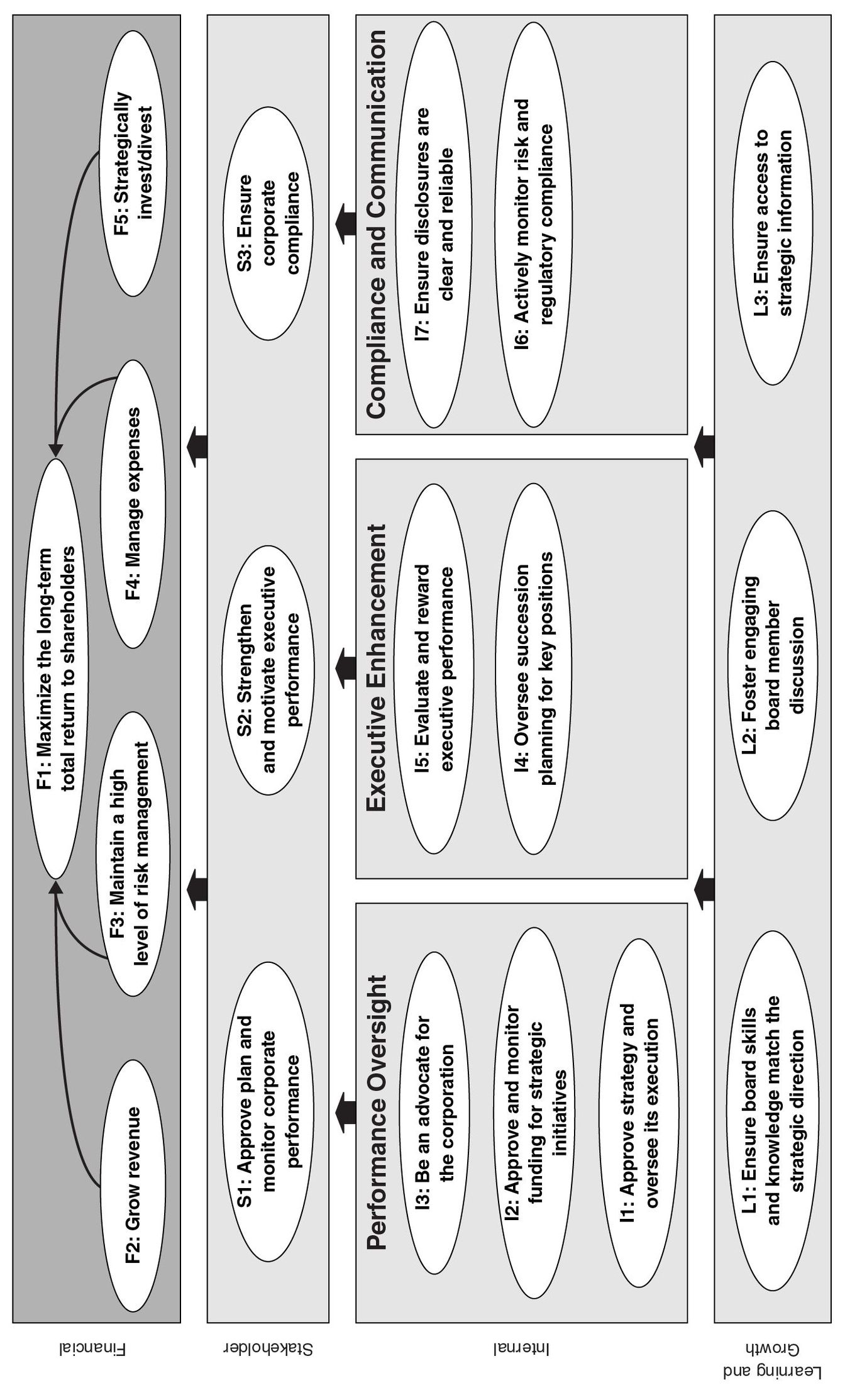

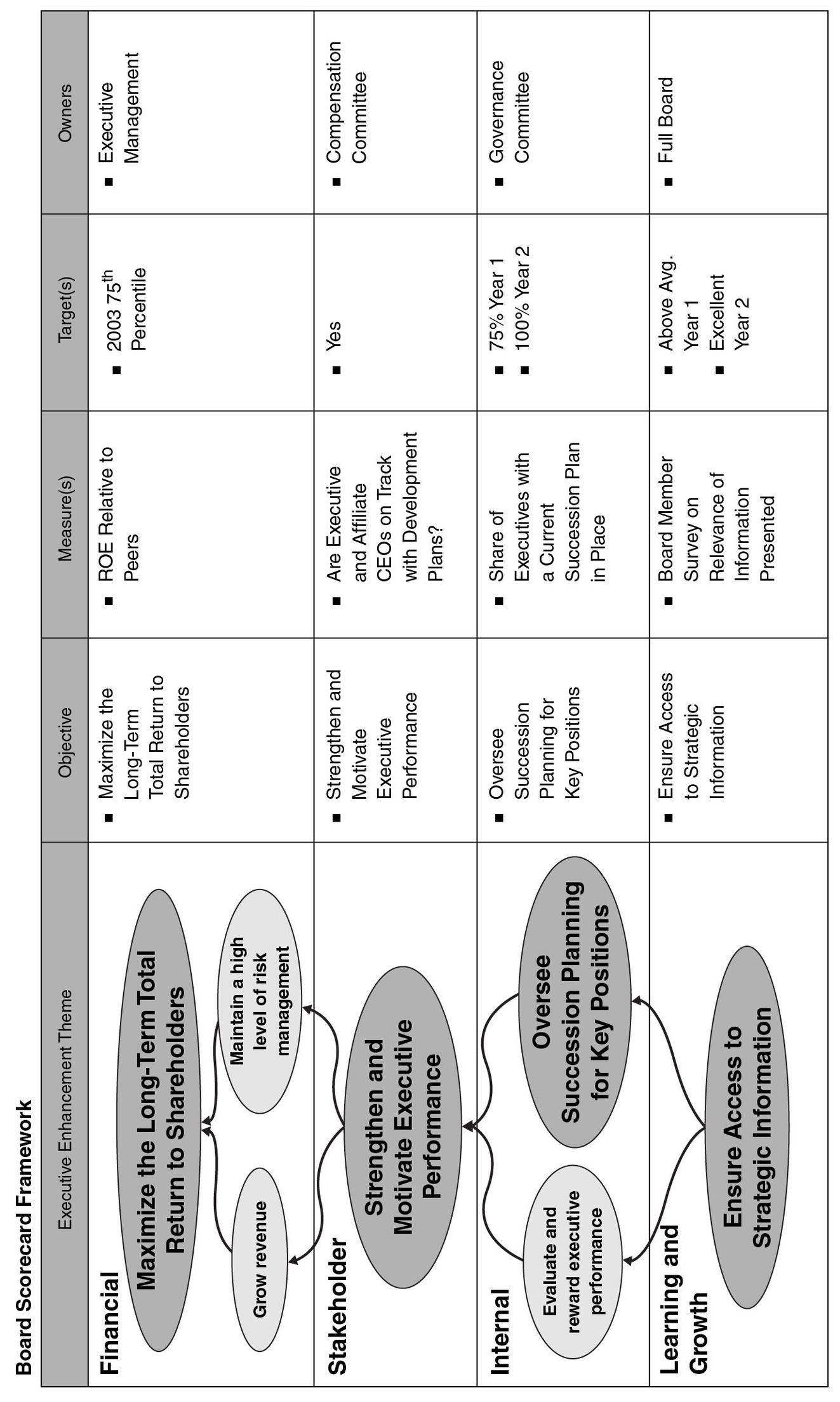

Consider the generic board Strategy Map shown in Figure 7-7, and a segment from the associated board Balanced Scorecard in Figure 7-8. The board Strategy Map typically uses financial objectives identical to those articulated in the enterprise Strategy Map, because ultimately the board’s success for shareholders is measured by its ability to guide the management team toward superior financial performance.

Rather than use the traditional customer perspective, however, the board scorecard introduces a stakeholder perspective, reflecting the board’s responsibilities to investors, regulators, and communities. As discussed earlier in this chapter, the board’s responsibilities to these stakeholders include the following:

- Approve, plan, and monitor enterprise performance

- Strengthen and evaluate executive performance

- Ensure enterprise compliance with regulations, laws, and community standards and use of adequate systems of internal control

These are the critical responsibilities that boards carry out to mitigate the moral hazard problems of managers acting in their self-interest rather than in the interests of their shareholders. The validation of financial reports and disclosures also provides investors with reliable information about investment opportunities and risks, thereby reducing the impact of hidden information.

The board is the single most important component in the entire system of capital market governance. It must ensure that managers are providing shareholders and regulators with valid financial and nonfinancial information, and that managers are using shareholders’ capital to advance the shareholders’ long-term interests. These board responsibilities are central to the effective functioning of capital markets. Unless investors can be assured that boards are carrying out these responsibilities objectively and independently, they will be reluctant to entrust their capital to enterprise managers.

The internal process perspective of the board’s scorecard contains the objectives for board processes that enable the board to meet its shareholder and stakeholder objectives. Figure 7-7 shows three strategic themes for board processes: performance oversight, executive enhancement, and compliance and communication. These themes provide the architecture for defining the specific internal process objectives of the board.

Figure 7-7 The Board Strategy Map Clarifies How the Board Contributes

Figure 7-8 Sample Board Committee Scorecard

The three strategic themes also link to the board’s most important committees. The governance committee has primary responsibility for performance oversight. The compensation committee has primary oversight for evaluating and motivating the senior executive team. The audit committee has primary responsibility for enterprise compliance and communication with external constituencies.

The learning and growth perspective of the board’s scorecard contains objectives for the skills, knowledge, and competencies of the board; the board’s access to information about the enterprise’s strategy and results; and board culture, especially the dynamics of productive board meetings that feature discussions and interactions among board members and the executive leadership team. The measures for the board’s learning and growth perspective can be generated from board member surveys, completed after each meeting, that assess the quality of the meeting, board processes, and information supplied in advance and during the meeting.

David Dahlmann, the vice chairman of First Commonwealth, commented on the importance of the board scorecard’s learning and growth objectives: “The board surveys help us determine if we have the right skills to help the company in its strategic direction, the right strategic information at the right time, and the right climate to encourage discussion and dissent.”15

In summary, as shown in Figure 7-9, a three-component Balanced Scorecard program—with an enterprise scorecard, executive scorecards, and a board scorecard—provides the information and the structure to help boards to be more effective and accountable for their vital responsibilities in an effective capital market governance system. The enterprise scorecard, supplemented by the scorecards for business units and key support units, informs the board in a succinct and powerful way about the strategies being implemented by the enterprise.

As it monitors, counsels, approves, and decides strategic direction, the board will operate with a much deeper understanding of the enterprise’s strategic context, and without its members being overloaded with excessive quantities of detailed information. Executive scorecards provide a clear basis for monitoring the management team’s performance, for compensating executives based on performance in meeting strategic targets, and for assessing the adequacy of executive succession plans. The board scorecard informs all board members of their responsibilities and facilitates periodic assessment of board performance using well-understood criteria.

Figure 7-9 A Three-Part BSC Program ls the Comerstone of the Corporate Governance System

ALIGNING INVESTORS AND ANALYSTS

Once the board approves and actively uses the enterprise’s Balanced Scorecard of financial and nonfinancial measures, the natural progression is to communicate some of this key information to the company’s owners. Several oversight committees, in fact, have advocated that Balanced Scorecard–type information about a company’s strategy and execution be communicated to investors. Fifteen years ago, a high-level committee of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (generally referred to as the Jenkins Committee, after its chairman, Edward Jenkins) investigated the information needs of investors and creditors.16 Among its recommendations were that companies provide, in addition to financial statements and measures, high-level operating data about a company’s business activities and performance measurements of a company’s key business processes. Such measures include the quality of the company’s products or services, the relative cost of its activities, and the time required to perform key activities, such as new product development.

The committee’s study indicated that analysts and owners were as interested in a company’s business activities, business processes, and events affecting the company as they were in financial measures. The committee report emphasized that high-level operating data would help analysts and owners understand the business—in particular, the link between events and activities and their impact on the company’s financial performance. The committee recognized that, in response to changes in their businesses, companies were changing their information systems and the types of information they use to manage their businesses, such as the performance of key processes for total quality management (TQM) and customer satisfaction measures. The committee concluded, “Users would benefit from greater access to the high-level performance measures management is using to manage the business.”

Ernst & Young studied the information used by financial analysts. It concluded that earnings are decreasingly important in predicting stock price and that “35 percent of a company’s valuation is attributable to nonfinancial information.”17 Analysts with the best track record for accuracy claimed to use the most nonfinancial measures. And in a more detailed investigation of four industry sectors—computer hardware, food, oil and gas, and pharmaceuticals—the study concluded that the nonfinancial metric most valued by investors was a company’s ability to execute its strategy.

A 1999 Harvard Business School study also concluded that leading sell-side analysts wanted more nonfinancial data from corporations’ external reports, including information about the competitive strategy of business units and the corporate strategy.18 Marc Epstein, in two coauthored studies, provided examples of several companies that included nonfinancial metrics in their annual reports.19

But despite all the studies documenting analysts’ desire to see information relating to a company’s strategy and its execution, the reporting of nonfinancial performance measures by corporations remains ad hoc and intermittent. Even with widespread adoption of the Balanced Scorecard for managing strategy within corporations, virtually no corporation has chosen to use the Balanced Scorecard framework for external reporting and disclosure.20

In the mid-1990s, after the success of several early adopters of the Balanced Scorecard—Mobil US Marketing & Refining, Cigna Property & Casualty, and Chemical Retail Bank—we spoke to the senior division executives about whether they used their Balanced Scorecard indicators in their communications with analysts and investors. Several had spoken to analysts about the recent success of their divisions. None actually presented the division’s Balanced Scorecard to the analyst community, but all structured their presentations to the analysts using the BSC framework. They reported that the analysts were highly enthusiastic about the presentation because the executives, instead of just discussing earnings per share growth rates and forecasts, actually described the underlying strategy that had led to recent and substantial improvements in financial performance.

For example, in one presentation, the executive explained how a major investment in new information technology had led to significant improvement in a customer-facing process, which in turn had led to higher customer retention and customer volume growth, a major contributor to recent growth in revenues and margins. The analysts could see that current results were not just luck; the executive had a specific strategy for value creation that his division was implementing successfully and was likely to sustain.

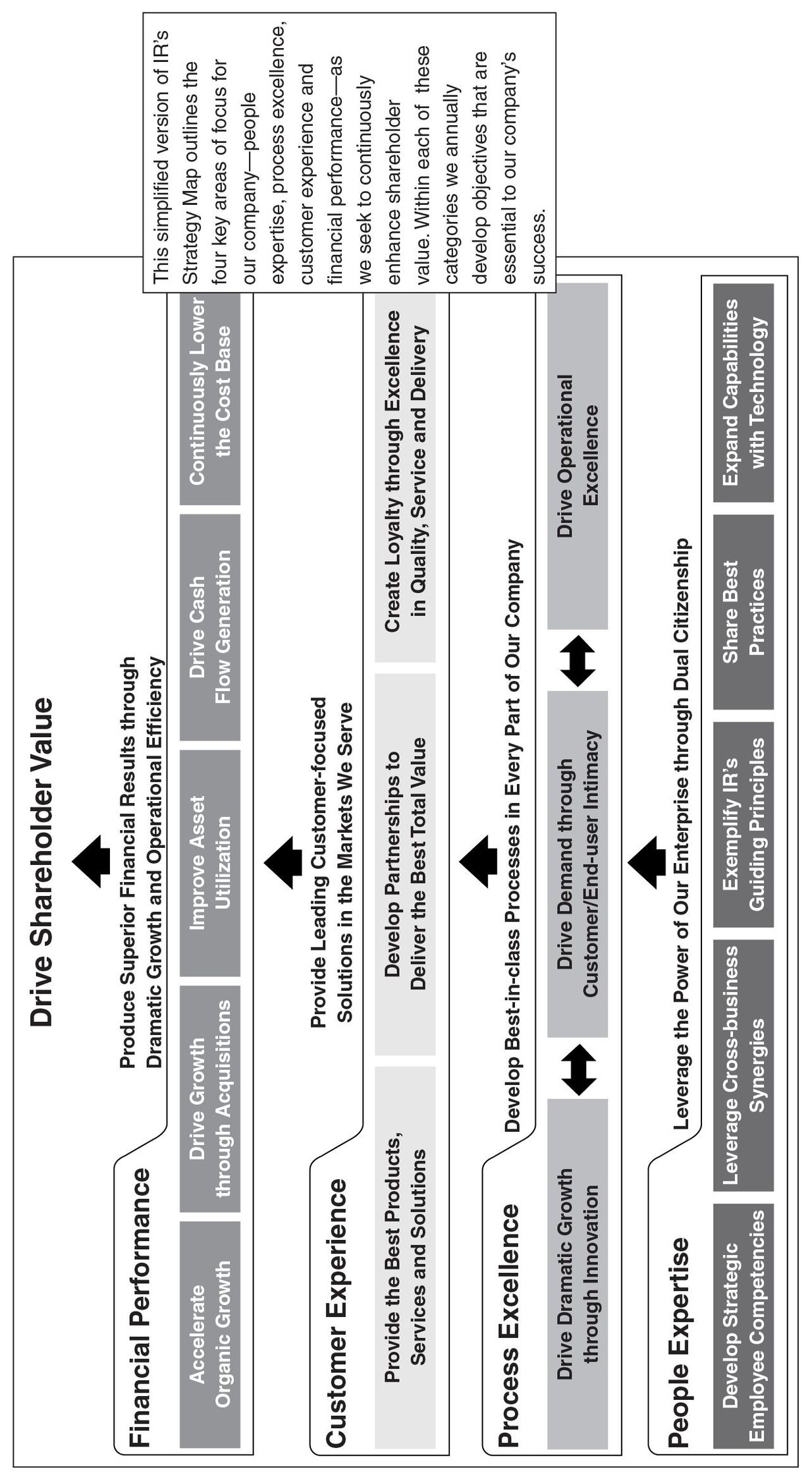

Ingersoll-Rand, a company discussed in Chapter 3, disclosed its high-level corporate strategy map in its 2002 annual report (see Figure 7-10). The Strategy Map shows high-level strategic objectives for all its businesses, but the report does not provide measures or data on the objectives. The disclosure was part of IR’s strategy to brand the company as capable of achieving economies of scope from its seemingly diverse businesses through an integrated corporate strategy. In IR’s 2003 annual report, the CEO’s letter described accomplishment in the corporate Balanced Scorecard themes: dramatic revenue growth through innovation and customer solutions, operational excellence, and dual citizenship. Similarly, each of IR’s four major sectors described its accomplishments using these corporate themes. In 2004, CEO Herb Henkel continued to use the framework in his quarterly presentation to analysts, providing specific examples of innovation-driven growth, cross-business customer solutions, operational excellence, and dual citizenship.21

Figure 7-10 Ingersoll-Rand Strategy Map in 2001 Annual Report

Source : IR 2001 Annual Report, page 9.

Wendy’s, the leading quick-service restaurant, also uses the scorecard framework in its presentations to analysts, although without explicitly mentioning that the metrics being reported come from the four perspectives in its Balanced Scorecard.22 Companies, like Wendy’s, that apply the same metrics for every business unit, of course, have more standardized metrics to report than companies consisting of diverse operating units, which may have few metrics in common. Quarterly, Wendy’s reports to analysts include the following measures:

| Financial | • | Sales growth per store |

| Customer | • | Customer satisfaction |

| • | Taste comparison versus competition | |

| • | Value to customers versus competition | |

| Internal Process | • | Service excellence (average drive-through time) |

| • | Order accuracy, drive-through service | |

| • | Cleanliness | |

| Learning and Growth | • | Friendly, courteous employees |

| • | Employee turnover |

Wendy’s believes it has gotten benefits from its consistent disclosure of key nonfinancial metrics related to its strategy. In January 2005, Wendy’s was named by Institutional Investor Research Group as having one of the best U.S. investor relations efforts. John Barker, vice president, investor relations and financial communications, stated, “Wendy’s stock price is up 75% since it started its [Balanced Scorecard], due in part to increased disclosure.”23 Barker’s remark suggests that companies’ enhanced disclosure may increase their valuations by giving analysts confidence that recent earnings improvements are due to effective strategy execution that can be sustained into the future.

In summary, external reporting of Balanced Scorecard measures is at a preliminary stage. Several companies have used the structure of their Balanced Scorecards to frame their presentations to analysts, although they have not explicitly incorporated the data reporting into their quarterly or annual reports. External reporting in the United States is done in an environment of extensive regulation and high litigation risk. Consequently, despite the apparent keen interest from investors and analysts in having greater information about corporate strategy and its execution, corporate executives seem reluctant to be entrepreneurial or innovative in their disclosure practices. Perhaps as corporations become more comfortable using the Balanced Scorecard to communicate strategic performance internally with business units, employees, and their boards of directors, they may, at some point, become more proactive in embedding Balanced Scorecard data in reports to investors and analysts.

SUMMARY

Although still in its early stages, the Balanced Scorecard is beginning to be used in corporate governance and reporting processes. Directors’ responsibilities are increasing, but the time they have available to perform their functions is not easily expanded. Directors must be able to do their jobs better and smarter, and not by working longer and harder.

A three-part BSC-based governance system offers directors streamlined and strategic information. In this way, board members have relevant information for their decisions about the company’s future directions and its reporting and disclosure policies. Preparation and meeting time focuses on the company’s strategy, its financing, and its most important drivers of value and risk. Executive scorecards inform the board’s processes for executive selection, evaluation, compensation, and succession. And the board itself has a scorecard to guide decisions about board composition, board processes and deliberations, and board evaluation.

For corporate reporting, various studies have documented the keen interest in having supplementary nonfinancial measurements that would help analysts and investors understand and monitor a company’s strategy. Several companies have started to use their Balanced Scorecard frameworks to structure their external communications. But this movement is still in its infancy, and more experimentation is required before most senior executives will become comfortable with supplying data to communicate and evaluate their strategies.

NOTES

J. Immelt, “Restoring Trust,” speech, New York Economic Club, November 4, 2002.

This analysis of the problems of adverse selection and moral hazard in capital markets is taken from K. G. Palepu, P. M. Healy, and V. L. Bernard, Business Analysis and Valuation Using Financial Statements: Text and Cases, 3rd edition (Mason, OH: Thomson Southwestern), 2003.

The breakdown in markets when buyers cannot get valid information about the product or service being offered for sale was described in a Nobel Prize–winning paper: G. A. Akerlof, “The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly J. Econ. 89 (1970): 488–500. Groucho Marx, in a much earlier publication than Akerlof’s, captured the essence of the adverse selection problem when he stated, “I don’t want to join any club that would accept me as a member.”

J. Conger, E. Lawler, and D. Finegold, Corporate Boards: New Strategies for Adding Value at the Top (New York: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2001).

J. Lorsch, “Smelling Smoke: Why Boards of Directors Need the Balanced Scorecard,” Balanced Scorecard Report (September–October 2002): 9–11.

E. E. Lawler, “Board Governance and Accountability,” Balanced Scorecard Report (January–February 1993): 12.

Ibid., 11.

Ibid., 10.

Details can be found in R. S. Kaplan, “First Commonwealth Financial Corporation,” Case 9-104-042 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2004).

J. Ross, “The Best-Practice Hamburger: How Wendy’s Enhances Performance with Its BSC,” Balanced Scorecard Report (July–August 2003): 5–7.

L. Bebchuk and J. Fried, Pay Without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004); G. Crystal, In Search of Excess: The Overcompensation of American Executives (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991).

J. Cohn and R. Khurana, “Strategy Maps for CEO Succession Planning,” Balanced Scorecard Report (July–August 2003): 8–10.

Ibid., 9.

M. J. Epstein and M. Roy, Measuring and Improving the Performance of Corporate Boards, Management Accounting Guidelines, Society of Management Accountants of Canada (Mississauga, Ontario, 2002).

Kaplan, “First Commonwealth Financial Corporation.”

“Improving Business Reporting—A Customer Focus: Meeting the Information Needs of Investors and Creditors,” Report of the Special Committee on Financial Reporting, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 1992.

“Measures That Matter,” Ernst & Young white paper, 1999 (available from Cap Gemini Ernst & Young Center for Business Innovation).

M. Epstein and K. Palepu, “What Financial Analysts Want,” Strategic Finance (April 1999).

M. Epstein and B. Birchard, Counting What Counts: Turning Corporate Accountability into Competitive Advantage (Reading, MA: Perseus Books, 1999); M. Epstein and P. Wisner, “Increasing Corporate Accountability: The External Disclosure of Balanced Scorecard Measures,” Balanced Scorecard Report (July–August 2001): 10–13.

One of the few exceptions is Skandia, a Swedish insurance company, which published its Navigator of nonfinancial measurements, for many years, as part of its annual report (see “The Value-Adding Power of External Disclosures: An Interview with Jan Hoffmeister, American Skandia Investment,” Balanced Scorecard Report (September–October 2001): 10–11.

See presentations at http://irco.com/investorrelations/analysts.

See Wendy’s analyst presentations at http://www.wendysinvest.com/main/pres.php.

“The Best-Practice Hamburger: How Wendy’s Enhances Performance with Its BSC,” Balanced Scorecard Report (July–August 2003): 6–7.