CHAPTER 11

Gathering Customer Information

In this chapter, you will learn about

• Communicating with clients, designers, and contractors

• Identifying client needs

• Interpreting scale drawings of the client site

• Identifying client contact information

• Evaluating possible constraints at the client site

This chapter covers the various types of information required to design and install an audiovisual (AV) solution at a client’s site. To obtain this information, you generally need knowledge of customer service and negotiation techniques, as well as an ability to interpret scale drawings and other project documentation. You also will need skills in basic math and listening techniques.

Duty Check

Questions addressing the knowledge and skills related to gathering customer information account for about 10 percent of your final score on the Certified Technology Specialist (CTS) exam (about 10 questions).

Communicating with Clients

CTS-certified AV personnel are able to communicate effectively and accurately with clients and the project teams. They know how to present themselves and to correspond in a professional manner. Repeat business from satisfied clients and word-of-mouth referrals are important to the professional AV business. If clients and business partners feel you’ve established a clear, open, and straightforward relationship, they’re more likely to do business with you again or recommend your work to others.

In communicating with clients and the project team, you will need to determine AV requirements by listening carefully and presenting AV-related questions, issues, and options. This section reviews strategies to improve your ability to communicate with clients, co-workers, and members of allied trades.

Obtaining Client Contact Information

It may sound obvious, but it is critical in the early stages of the project—and throughout the design and installation—that you have the correct and proper contact information to ensure that you can communicate with the client in a timely manner. The contact information should include any participants or stakeholders that you may need to contact throughout the project, such as the architect, building manager, AV manager, information technology (IT) manager, and so on.

The following is the typical contact information necessary to collect at initial meetings:

• Mobile phone number This is the critical number to have in the event that you need to contact a client team member immediately to address an issue in a timely manner. A mobile phone number will also allow you to transmit and receive Short Message Service (SMS) text messages.

• Landline telephone number This is the fixed-line telephone number and extension, used for contact during business hours or as a message store for out-of-hours voice-mail messages.

• E-mail address E-mail is the primary channel for written business communication, particularly when you need to retain the content of the messages for your records. E-mail attachments provide a timely means for communicating contract details, plans, reports, presentations, visualizations, and demonstration videos.

• Messaging ID A brief communication can often be handled through Internet messaging via a computer or mobile phone. With the wide variety of messaging applications available, it is important to establish a mutually convenient platform. Many messaging systems can also be used to conduct video conferencing to share and discuss plans and documents. If an archiving facility is available on the selected platform, this can serve as an archive of matters raised in chat sessions.

• Postal address The full physical mailing address should be recorded for sending hard copy of communications, contracts, plans, and other documents.

Face-to-Face Communication

It almost goes without saying, but face-to-face communication is the most direct method of communicating on a project. Looking at a person helps you gauge that person’s competence, establish a rapport, and assess the reaction to your message. By sitting down and talking directly to clients and the project team, you may be able to assess the following:

• Is this person knowledgeable?

• Is this person trustworthy?

• Is this person listening?

• Does this person care about your message?

Also, in a face-to-face conversation, you can use a number of strategies to communicate that you yourself are competent, trustworthy, and sincere.

Personal Appearance

In face-to-face communication, your overall appearance sends the first message to the client. Clients usually feel more confident in your abilities if you appear professional. Make sure you dress appropriately. Wear neat, professional-looking clothing. Tuck in your shirt and wear a belt. Wear modest clothes that cover you up when you are working. Avoid clothing with logos or advertising (with the exception of your organization’s branded apparel).

Many companies provide uniforms or have a dress code that you should follow. If you are unsure what to wear, talk to your manager.

Body Language

Your body language also sends a message. Nonverbal communication can sometimes be as important as verbal communication when speaking to a client. Keep the following tips in mind when meeting with clients:

• Smile when you greet clients and when you close your business. A smile conveys a positive and friendly attitude that will help establish rapport.

• Introduce yourself and shake clients’ hands. Do not wait for clients to make the first move.

• Stand up straight and don’t slouch. Slouching can make you appear like you lack confidence, energy, or even competence.

• When clients are speaking, face them, smile, and listen to what they are saying.

• Observe clients’ body language. Do they seem uncomfortable or nervous? If so, adjust your responses based on that impression. If they appear confused, simplify your explanation or statement and then ask if they have questions.

Active Listening

Active listening is critical to effective communications. When someone is speaking, it is easy to fall into the pattern of thinking about what you will say once that person is finished talking. Unfortunately, that can prevent you from hearing what the other person is actually saying. Here are some tips to improve your client listening skills:

• Stop what you are doing and look at the person who is speaking to you.

• Maintain eye contact with the client. If you are wearing sunglasses, remove them so the other person can see your eyes.

• Focus on what the client is saying, instead of planning what you will say when the client is finished speaking.

• If you understand what the client is saying, nod your head to indicate so.

• When appropriate, repeat or summarize the main points of what the client is saying using your own words (paraphrase), and provide some feedback to confirm that you understand.

• Ask questions, when necessary, to clarify your understanding of what the client is saying.

• Let the client speak freely. Do not dominate the conversation, interrupt, or jump in to finish people’s statements.

Sensitive Topics

Handle sensitive topics carefully. How you express what you need to say can be just as important as the content of your statement. There can be cognitive effects from the logic you use to phrase your message, emotional effects from the empathy you show while delivering your message, and legal effects from the implications your message leaves. Consider the following strategies for sensitive communication when responding to client statements or questions:

• Preface questions with statements such as, “To make sure I understand . . . ,” which tells clients that you are taking responsibility for understanding their needs.

• State your question as concisely as possible.

• Consider past experiences with other clients and formulate questions to clear up any common areas of misconception.

• Phrase your comments and questions carefully to avoid confusion or insult. Vague phrasing can make the client question your abilities to help. Seemingly confrontational or accusatory wording can put the client on the defensive.

• Be conscious of your tone of voice and facial expressions.

• Address the client’s concerns in a straightforward way and keep to the point.

• Explain pertinent terms in plain language and avoid jargon. Be tactful when the client doesn’t seem to understand. No one likes to feel stupid, so protect the client’s feelings. This is especially important if your client is a presenter about to face an audience.

• Answer every question asked, even if the answer is, “I’m sorry, but I’ll have to check and get back to you.”

Conflicts

Managing conflict or working with challenging clients can be difficult. Challenging clients are not always negative clients; rather, they are clients who may not be easy to serve. When conflicts arise, the following may be helpful:

• Be calm and polite.

• Listen and be supportive.

• Try saying, “I can see that you are upset. I apologize . . . .”

• Remember that clients are not allowed to verbally assault you.

Generally, you may encounter argumentative, overly talkative, and “know-it-all” types of clients who require special handling. With argumentative clients, keep these points in mind:

• Do not make the situation worse with a negative comment.

• Listen to what they are saying and try to figure out why they are rejecting your suggestions.

Overly talkative clients can also cause problems. You might deal with them as follows:

• Never assume you know what they need and interrupt.

• Details can be important when you are trying to solve a problem. Try to listen for the exact nature of the problem.

“Know-it-all” clients can be another source of conflict. Keep these points in mind:

• These clients may react to your assistance with a solution of their own.

• They may interrupt you, telling you what they know.

• Sometimes their suggestion is a great solution, so be open to possibilities.

• Listen to the client before responding.

Don’t forget that you can contact your supervisor for advice when a situation becomes unmanageable.

Language Barriers

Language barriers may also impact your ability to communicate effectively. If you are providing assistance to someone who speaks a language other than your own, you may need to do one or more of the following:

• Speak slowly and clearly, and do not increase your volume.

• Use plain language.

• Avoid slang and local phrases. Remember that it is hard enough to comprehend an unfamiliar language, so do not complicate it.

• Avoid jargon and acronyms unless the person is technically proficient.

• If the client asks you to repeat something, do not respond with increased volume.

• Write, draw, gesture, and demonstrate to show clients that it is important to you that they understand.

• Diagrams can be a helpful form of communication. Math can help as well. If you can figure out how to demonstrate a concept visually or mathematically, it may overcome a language barrier.

Speaking on the Phone

Your initial contact with a potential client will often be on the telephone. During that first conversation, people will draw conclusions and make judgments about your business skills. If you are professional and knowledgeable, clients will likely return for your services. It is essential to the image of your company that you understand how to communicate over the phone successfully. Here are some suggestions to improve your telephone communication skills:

• Speak in a natural, friendly tone of voice.

• Smile. Your smile will not be seen, but it will make your voice sound friendlier.

• If you initiate the call, start off with your first and last name, the name of your company, and the reason for your call.

• No matter who placed the call, use the client’s name frequently. Listen to the client’s general tone and the way the name is given to determine how to address the client, such as whether to use just a first name or be more formal.

• Practice active listening. Give the call your full concentration.

• Strive to be clear in your communication because you won’t have the advantage of visual aids to help communicate your message.

• Keep your tone positive even if the caller has a complaint. Offer solutions, never excuses.

• Take notes when the discussion is detailed.

• Verify the client’s factual information by reading from your notes or from an existing file.

• Keep in mind that some procedures are too complicated to explain over the phone. If this is the case, suggest meeting in person so that you can provide the details.

• If you feel that there is a language barrier, find someone who is familiar with the client’s language and the technology to help interpret. Alternatively, suggest a different form of communication.

One challenge of telephone communication is that clients’ descriptions of problems or needs are often subject to their own interpretations. Too often, clients assume that they understand the nature of the issue and leave important details out of the discussion. To overcome this, you must carefully word your questions in a manner that provides an objective description of the issue or problem, or arrange a meeting at the site to be able to personally examine the issue.

Business Writing

In pro AV, as in any business, written communication can take many different forms, such as e-mail messages, text messages, online chats, and letters. To write effectively using any of these forms, it is important to organize your writing, keep your audience’s needs in mind, and follow basic grammatical rules. To successfully communicate in all these forms of writing, you should follow some basic guidelines:

• Begin by informally listing the points you want to make for your own notes and then set about writing the content.

• In business writing, it is appropriate to begin, “The purpose of this [e-mail/message/letter] is to [assist/inform/report/confirm] . . . .”

• Creative, verbose, or academic writing styles are not ideal for business communication.

• After writing, compare the message to your initial list of important points.

• Eliminate any information that does not pertain to these points.

• Use meaningful details and do not ramble.

• Check your spelling, sentence structure, grammar, and punctuation.

• If you are delivering bad news, focus on what you are doing to fix the problem.

• Do not use technical jargon, acronyms or textspeak abbreviations (such as LOL, BTW, OMG) that your audience will not understand.

• Do not type in all capital letters.

• Use an easily legible font.

• What you write is a reflection of you and your company. Remember that it may be reproduced and sent to anyone—prospective clients, competitors, superiors within your company, other people at the client’s company, or even the media.

• If you have any doubt about the content of your communication, refer it to a suitably skilled colleague for checking.

Some forms of writing require a more formal style than others. However, to write effectively in any form, you should follow the guidelines presented here.

Choice of Communication Form

With so many forms of communication to choose from, how do you decide which one to use? You obviously want to use the form of communication that allows you to communicate both accurately and efficiently with your clients. Be aware of your own preferences, and don’t allow your personal feelings to influence your choice. Practice with different forms of communication and think of your client’s preferences before your own. Consider these questions when selecting a form of communication for your client:

• With which forms of communication does your client contact you?

• With which type of communication will you fulfill your client’s need?

• Which form of communication is most efficient for your client and you?

If you have several options of communicating, choose a form that your client is comfortable using. This will decrease the likelihood of clients missing messages, and it will make the interaction more comfortable for them. You may need to consider installing and learning the operation of the communications or collaboration platforms preferred by the client.

For many businesses, e-mail messages have effectively replaced hard-copy mail communications. However, the more details you put into an e-mail message, the greater chance you have of losing your audience.

People typically do not like sending or receiving lengthy, technical e-mail messages with excessive information, and many may not scroll through the entire document. Instead of an overly detailed message, send specific precise directions or information, and include attached documents containing a thorough explanation.

When sending e-mail messages, keep the following in mind:

• Verify that the e-mail address is correct.

• Ensure that the subject line reflects the main topic of your message. If the topic in a long e-mail exchange chain changes over time, it is important to update the subject line to match the new discussion.

• Simply address the recipient using the client’s name. It is not necessary to use “dear” in the greeting.

• Respond to e-mail in a reasonable amount of time, even if only to inform the client that an answer to the request is in progress.

• Do not conduct personal business using a company e-mail account.

• Do not gossip in e-mail. That is unprofessional, and your message could accidentally be forwarded to an undesired recipient.

• Include alternate contact information such as your telephone numbers and messaging IDs in the signature area.

• Avoid making jokes. Even the most well-intentioned jokes can be misunderstood.

• Know when to stop. If your conversation on a particular detailed matter goes longer than three e-mail exchanges, call the client for the sake of time efficiency.

• Take care when sending e-mail—you never know who may read it and how it will affect your company, your reputation, and your career. The best advice is to always assume that all e-mail could become public with no warning. If you must provide confidential company information, include only information that is required to communicate clearly. It may be appropriate to mark the e-mail “Confidential” or to set a “Do Not Forward” flag if it is available in your e-mail system.

• Consider the method your intended recipient has used to contact you. If the customer typically uses a telephone to contact you, then you should use the phone to reply. If you decide the most accurate way to convey your message is using e-mail and attachments, call the client first and explain that you will reply in e-mail form.

Messaging and Online Chat

Messaging and online chat are excellent ways to conduct brief, impromptu discussions internally and with clients. Online chat is intended to be informal, but there are still a few guidelines that apply.

• Conversations should consist of only a few words and quick responses. If the client is asking a question that requires a longer explanation, choose a different form of communication.

• For those who have trouble with proper grammar, there is less expectation for accuracy because of the fast-paced nature of chatting.

• The nature of online chat has generated a need to abbreviate. Emoticons and acronyms are commonplace in online chat sessions, but be aware that they may not be understood by all of your clients.

• When answering questions, be accurate. Incorrect information can be recorded and repeated.

Legal Ramifications

There may be legal implications to your client communications, so be careful, even with your co-workers. Restrictions on disclosing confidential or proprietary information may lead to legal action against individuals who reveal information about a company. Even repeating simple gossip can lead to rumors that become public, and you may find yourself named as the source of sensitive information. Write as if your communication will be published on the evening news or the front page of a national newspaper—it just might.

Obtaining Information About Client Needs

Meetings with clients can happen at various times during a project, depending on many variables. One of the most important variables is when in the process the AV professional joins the project team.

AV designers and installers may be brought into a project at any stage of the production or design and construction process. In some cases, an AV company is contacted after an architect or production designer has already designed the building or space. When certain aspects of the project cannot be modified to create a suitable AV environment, it can compromise the effectiveness of the AV systems. Moreover, requiring changes to existing designs to support an AV system may result in additional cost.

In other cases, AV integrators or designers are hired at the beginning stages of a project. This allows for including the required infrastructure into the original project design, typically leading to a more successful AV environment.

In either case, the AV team should know at what point in the project the team is beginning its role, because that will help determine the agenda for early client meetings. During those initial meetings with the client, the AV team must determine exactly what the client needs to address their AV requirements, including the services, infrastructure, staffing, and equipment.

Conducting Initial Meetings with the Client and End Users

The main objective of the initial client meetings is to gain an understanding of the end users’ needs. The goal is to develop an AV design document that will include descriptions of the needed systems, along with preliminary budgets.

Depending on the scope of the project and the number of users to be interviewed, client meetings can take many forms. For example, you may have a single meeting with a few individuals that lasts for a few hours. Alternatively, you may have a series of meetings with different groups over several days. Regardless of the size and duration of the meetings, the issues to be addressed are the same: the functions that the system will need to support.

Best Practice: Focus on Functionality, Not Equipment

All participants in AV design meetings should understand that the goal of the meeting is to determine functionality, not equipment. While some discussion of equipment is inevitable (especially in short-term projects), the meeting should address the functionality required to address the users’ needs.

For example, large image displays such as projectors, light-emitting diode (LED) screens, and video walls often come up in discussions because they can impact both the budget and the project design. But a discussion of the image displays during an initial client meeting should focus more on what users want to achieve with the images than on the technologies to be used. How many images do users need to support their tasks? What image sources need to be displayed? At what aspect ratio and resolution should the images appear to support users’ tasks? How much ambient light will be present? The answers to questions like these will determine the image display technology that you ultimately specify.

Client meetings to identify needs should typically be attended by the following people:

• Administrative representatives/stakeholders, including owner executives, facility managers, department heads, and funding organizations

• End users, including representatives from each organization or department that will use the new systems

• AV technology managers, representing the technical side of the client’s AV operational needs

• IT representatives, to address issues in utilizing or accessing the IT system and how IT relates to the users’ activities

• Architects and project designers, to provide input regarding space allocation and planning

• Program, production, or construction managers, who may be stakeholders in the overall project outcome

If people outside the client’s immediate organization will be using the AV systems (as in facilities for hire or a classroom building serving several departments), their perspectives should be represented whenever possible.

Conducting a Needs Analysis

The needs analysis is the most important part of the AV design process because the results determine the nature of the AV systems, their infrastructure, and the budget, including the impact of AV-related expenses on the project.

The goal of the needs analysis is to define the functional requirements of the AV systems based on the users’ needs and desires and on how the systems will be applied to perform specific tasks. Merely developing an equipment list is not enough. While the equipment list is an essential part of the design and installation process, it is not part of the needs analysis. It is tempting—particularly from a sales perspective—to go straight to an equipment list. However, only by analyzing the users’ needs can you ensure that you address them fully through the selected equipment and system design.

A formal needs analysis includes identifying the activities that end users must perform and developing the functional descriptions of the systems that support those needs. During the needs analysis phase (which is known as the programming phase in the architectural trades), the AV professional determines the end users’ needs by examining the following:

• The specific activities the end users want to accomplish within the space/room

• The required AV presentation applications based on the users’ needs

• The tasks and functions that support the applications

The result of this needs analysis is a thorough understanding of which types of presentation system capabilities the users require to support their desired activities. These needs are translated into a detailed document, often called the program report or brief, that delineates the overall functional needs of the AV system (including budgets), based on the tasks the owner requires for operation. (We will cover the program report in more detail in Chapter 15.)

Understand a Need When You Hear It

The following are some typical examples of end users’ needs:

• To communicate with staff within a company

• To save money on travel while enhancing face-to-face communication

• To support and operate a conference center

• To engage visitors with a museum display

• To host many different types of events in the same venue

• To provide adult education

• To market or sell a product

• To improve situational awareness for a federal, state, or local government agency

• To monitor and operate an area-wide, nationwide, or worldwide network

• To stage productions and events in a performing arts, sports, or themed entertainment venue

• To enhance the worship experience

• To inform and engage visitors to a shopping center

• To provide primary and secondary education in multiple locations

The needs analysis pyramid, shown in Figure 11-1, illustrates both top-down and bottom-up approaches to examining end users’ needs. The needs determine the applications that are required to support them, which in turn determine the functionality of the required AV systems (the equipment). Based on this information, you can determine some of the necessary infrastructure for the overall space (architectural, acoustic, electrical, and mechanical).

Figure 11-1 The needs analysis pyramid

Facility Function

In some cases, the needs that the AV system must address are determined by the room. The facility type or room function is often known before the first client meetings. For example, maybe the client is building a new classroom, night club, distance-learning center, corporate-training center, headquarters, performing arts center, shopping complex, boardroom, or network operations center. The facility or room type often has well-established AV system requirements that can address the typical users’ applications within the room.

The following are some examples of standard rooms that AV designers and integrators work on:

• Boardroom or conference room These are usually richly appointed rooms where interactive meetings are held, generally attended by the executives of a company. Most clients want these spaces to look impressive, which usually requires that all equipment be aesthetically integrated into the space. Seating is around a conference table, typically positioned in the center of the room. The presentation is made from one of three locations.

• At the head of the table, with the video screen behind the presenter

• From a lectern, with the video screen to either the left or the right of the presenter

• From the end of the table that faces the video screen (see Figure 11-2)

Figure 11-2 Screen installation in a typical meeting roo

• Training room, lecture theater, or classroom This type of space tends to be multifunctional, meaning it needs to handle various types of presentations and AV applications. People are typically seated classroom-style at desks or theater-style in rows of seats. Presentations are usually given from the front of the room, commonly from a lectern, with the presenter or teacher to one side of one or more displays or screens.

• Huddle room This is a meeting room used by small groups—usually fewer than 10—to collaborate interactively on projects, using presentation, collaboration, and teleconferencing facilities. The presenter may be seated at the conference table or standing by an interactive screen. Remote participants may also join the meeting via video and/or audio conferencing.

• Auditorium This is a large space, commonly used for one-way presentations, screenings, and performances to large audience groups. Presentations are usually from a stage at the front of the room. For screenings, a large central screen is generally used. For presentations additional side screens may be used. For productions and performances, the screens and sound system are frequently configured specifically for each event.

• Divisible spaces This refers to a large area that can function as one large room or be divided into several rooms, each hosting its own event. For example, hotels and convention centers have large multipurpose spaces with sliding walls that are used to define room spaces. The shape and size of these rooms can be changed easily and quickly to accommodate the size of the group.

• Videoconference room This is a space designed for meetings via two-way video and audio links. Presentations may be made from specific locations in the room, which have been preprogrammed into the system. The space may also be used as a general-purpose conference room. Depending on need, these rooms can be designed so that the parties on either end appear as if they were in the same physical location.

Knowing the intended function of a room (or rooms, on larger projects) gives the AV team a starting point for determining client needs. Each of these types of rooms has standard technical requirements that the AV designer will be expected to address. Each room also presents specific design challenges. For example, certain videoconferencing rooms require that the space provide specific sightlines, lighting, and acoustical treatments. Large, divisible rooms are often subject to excessive sound reverberation and echoes, requiring the designer to pay special attention to room acoustics and sound reinforcement. Auditoriums often require extensive audio, staging, communications, and video infrastructure to provide for a wide range of possible production, presentation, and performance configurations.

A Word About Client Politics

At times, relationships within the client’s organization may affect how meetings are scheduled, attended, and managed. It is important to identify the differences among end users, decision-makers, and funding groups. If they are separate entities, conflicts may arise among what end users say they need/want, what decision-makers think end users need, and what the finance group is willing to spend money on. If the design team can decipher these relationships before any meetings are held, the meeting leader can be sensitive to potential problems in addressing each group’s issues.

AV Tasks and Parameters

Once you have determined what activities will take place in a room and which AV applications are required to support them, you need to get more granular and identify the specific AV tasks that the system will handle, as well as the parameters of those tasks. This information helps establish system configurations and budgets.

One common AV task that supports many AV applications is image display. For this task, the following parameters might be identified:

• Image sources

• Signal types to be displayed

• Aspect ratio of sources

• Number of simultaneous images

• Source resolutions and formats

• Display distance from viewers

• Duty cycle of displays

These parameters feed into the design process to inform the team about both facility requirements (display size, room size, room configuration, lighting, etc.) and system requirements (type and brightness of projectors or displays, number of inputs, video storage and systems, video-switching requirements, etc.).

Another common task is audio playback, which could have the following parameters:

• Audio signal types

• Number and type of audio sources

• Area to be covered by loudspeakers

• Multichannel replay formats

• Distribution of audio to other locations

You should also seek out information about infrastructure issues that might impact the AV design and installation. The following are some of the issues to cover:

• Space allocation If space has already been allocated to the AV systems, part of your assessment should be to verify that the space will accommodate the application.

• Is there adequate seating and workspace area?

• Is there adequate accommodation for a presenter and lectern or podium, if needed?

• Are adequate sightlines possible?

• Is there adequate space for equipment, including rear-projection, control, or equipment rooms, if needed?

• What are the sizes and locations of the required images, and can they be accommodated?

• What issues related to acoustics; rigging; staging; lighting; and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) might have an impact on the overall project budget and space allocation?

• Security What are the hours of operation for each area of the facility that will house the AV systems?

• What access restrictions will apply to the areas that will house the AV systems?

• Electrical/lighting There are several issues related to electrical and lighting systems. Ask yourself and the client the following questions:

• Is a lighting control system required?

• What areas require zoned lighting?

• Are control interfaces required for lighting, security, fire protection, drapes, rigging, staging, shades, or other systems that are not included under the AV scope of work?

• Are specialized lighting systems required for videoconferencing or performing-arts functions?

• Will there be additional or special electrical systems dedicated to the AV systems?

• Is an uninterruptable power system available or required?

• Data/telecommunications Are special or additional data/telecom outlets, patching, and distribution facilities required for audio, video, communications, or control systems?

• Is network access available for the AV project, and what are the network security requirements?

• Structural Is the building structure capable of supporting screen, projector, lighting, and loudspeaker mounting and suspension systems?

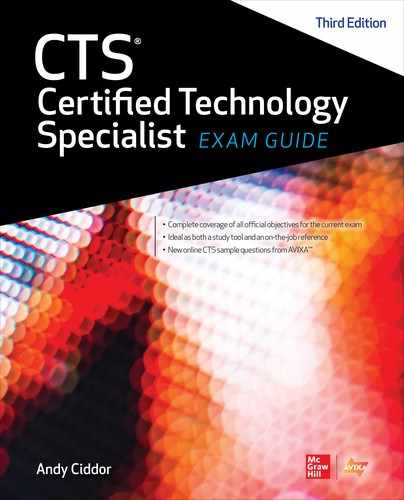

Table 11-1 shows possible AV tasks and parameters to support end users’ applications and needs. This gives you an idea of the type and level of detail you need to create the AV system design specification and budget.

Table 11-1 AV Task Parameters

AV Needs Analysis Meeting Agenda

The following example of an AV program meeting agenda shows some typical issues and items for discussion. Note that the specification process may require several meetings to interact with different stakeholder and end-user groups.

AV System Needs Analysis Meeting Agenda

Overview

A. Project overview

1. Identify project type.

2. Identify project schedule.

3. Identify major project applications required for end users’ operations.

4. Identify user groups and functions.

B. Identification of owner and end-user vision and style

C. Differentiation of AV system functionality versus AV equipment

Define expectations of the process.

1. What is needed/expected from the design team?

2. What is needed/expected from the owner/user?

3. How will the design team and owner/user communicate?

4. System quality

D. Technology trends

Review Existing Documents, Facilities, and Infrastructure

A. Review pertinent parts of architectural program.

B. Review any existing AV program information.

C. Tour existing facilities.

Identify User Functions

A. Existing functions

B. Anticipated functions

Identify Overall User Standards and Requirements

A. Standards

B. Benchmarks

C. Known connectivity requirements

D. Known basic AV requirements

E. Internal tech support availability

F. Accessibility considerations for disabled people as required by authorities having jurisdiction (AHJ)

Discuss Each Space or Area

A. Identify each area that requires a system.

B. Conduct a functional review of each space.

1. Functions required for each space

2. Operational requirements (day, night, remote monitoring, etc.)

C. Identify AV tasks and parameters for each area.

1. Identify major equipment requirements (number of images required, room size and seating, conferencing required, audio and video sources, etc.).

2. Identify potential impact on infrastructure.

(a) HVAC

(b) Security

(c) Electrical

(d) Lighting

(e) Data/telecom

D. Identify owner-furnished equipment.

E. Review budget issues and set priorities.

Conclusion

A. Identify key individuals and contact information for follow-up.

B. Identify follow-up meetings.

C. Discuss schedule for completion and distribution of report.

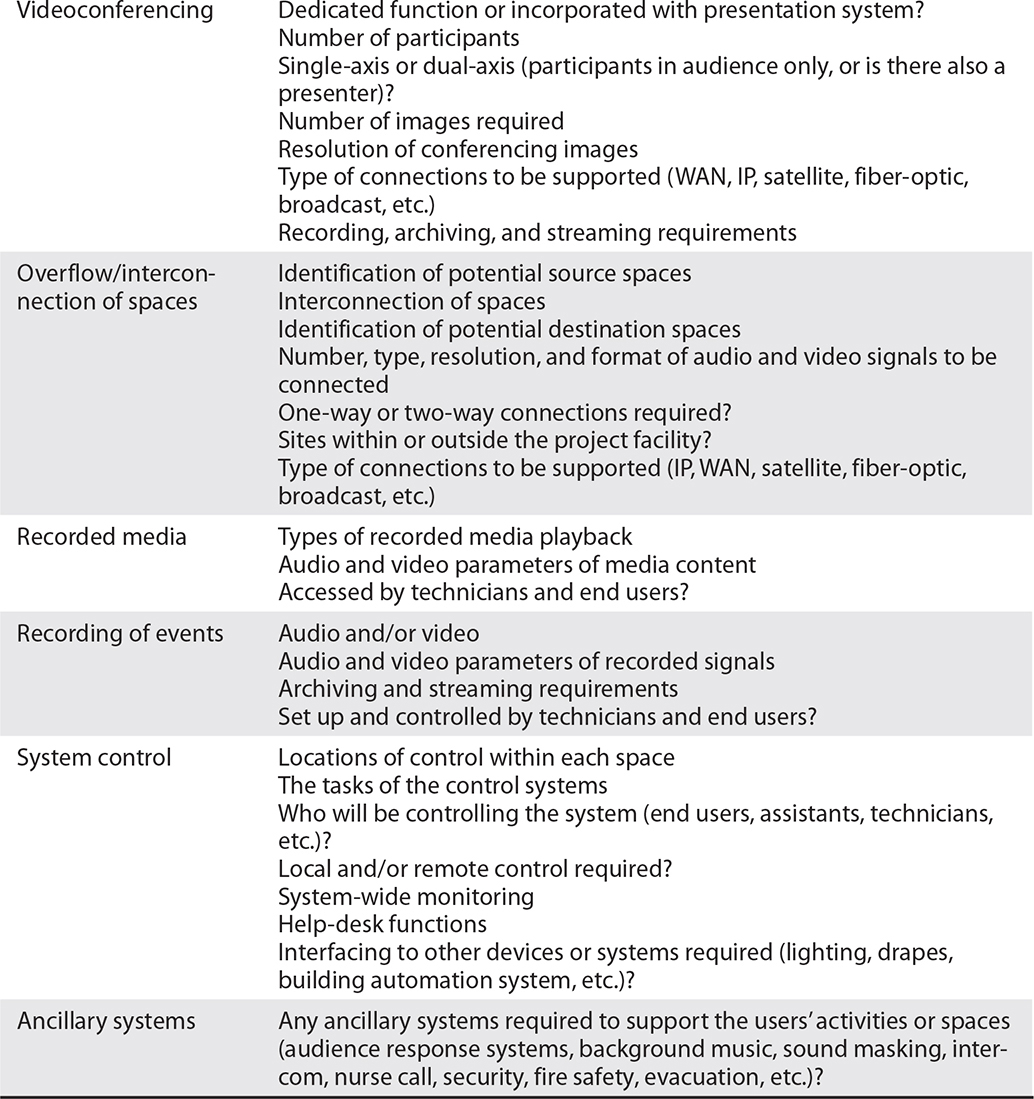

Figure 11-3 shows an overview of how the end users’ needs ultimately define the design team’s ability to create the required AV systems, and how the AV systems have an impact on the architectural, electrical, and mechanical infrastructure design.

Figure 11-3 Translating needs into a design

Benchmarking

Benchmarking refers to the process of examining methods, techniques, and principles from peer organizations and facilities. AV designers and integrators can use these benchmarks as a basis for designing a new or renovated facility. For example, a client may identify a specific existing facility that provides capabilities or design elements that the client would like included in the facility your company will design.

Benchmarking Benefits

Benchmarking offers the owner and the design team a common (and sometimes expanded) vision of what the client wants and needs. Seeing a number of locations of similar size, scope, and functionality can help guide a new facility design. Benchmarking offers the following benefits:

• It provides an opportunity to see varying approaches to design versus budget decisions.

• It allows project stakeholders to open a line of communication with other building managers and end users to evaluate what they learned through the design and construction process and to discuss what they would do the same or differently if they did it over again.

• It may inspire new design ideas.

• The team can identify successful (and unsuccessful) designs and installations that include elements that relate to their project.

• It can help to determine which functions and designs are most applicable to the current project.

Benchmarking Site Visits

During a benchmarking site visit, the AV team and the client should collect information about site characteristics they intend to consider during design and/or installation. The main objective is to identify desirable AV features and functionality.

Arranging a benchmarking trip involves the following steps:

• Determine appropriate facility types to visit. These may be a precise match to the owner’s operation, or they may be facilities with similar functions and operational needs.

• Create a list of potential facilities to visit.

• Check whether the benchmark sites allow such visits. Some benchmark visits may only require a user’s perspective of a public facility, but often you will want to visit a private facility, for which you need permission to enter. If you are planning to benchmark a secure facility—in support of a government or healthcare project, for instance—you may also need to gain security clearance.

• Most benchmarking visits benefit from a behind-the-scenes tour, which may require coordination with the technical staff, including those who support the facilities computer networks.

• Narrow down the options to a final list.

• Determine who will go. The benchmark group may draw from the end users, the owner’s technical staff, the owner’s administrative managers, and the architectural or design team, as well as the AV provider.

• Schedule and make the visits.

• Write a benchmarking report summarizing the sites visited, the pros and cons of each site, what impact there is on the client’s anticipated needs, and the resulting AV systems that will support those needs.

The following checklist provides examples of useful information you may want to collect during a benchmarking site visit. Once the benchmarking tour is set up, use this list to make the most of the visit and glean information that will be useful to the design team, owner, and end users.

Benchmarking Checklist

Facility Information

![]() Organization, facility, and location

Organization, facility, and location

![]() Contacts at the benchmark organization

Contacts at the benchmark organization

![]() AV project installation date

AV project installation date

![]() AV budget at time of installation

AV budget at time of installation

![]() Delivery method used for the project

Delivery method used for the project

![]() Style of the project: low-, mid-, or high-end

Style of the project: low-, mid-, or high-end

![]() Is there any facility or system documentation that can be shared with the design team?

Is there any facility or system documentation that can be shared with the design team?

![]() Is photography allowed?

Is photography allowed?

Benchmark Information

![]() What is the benchmark facility’s focus?

What is the benchmark facility’s focus?

![]() How is it like the facility you are working on?

How is it like the facility you are working on?

![]() How is it different?

How is it different?

![]() What technologies are used, and how do they support the end users’ activities?

What technologies are used, and how do they support the end users’ activities?

Features As They Relate to the Project Under Design

![]() Audio systems

Audio systems

![]() Video systems

Video systems

![]() Control systems

Control systems

![]() Local-area and wide-area networks

Local-area and wide-area networks

![]() Integration with IT

Integration with IT

![]() Lighting

Lighting

![]() Acoustics

Acoustics

![]() What technologies, design approaches, or criteria were used at the benchmark facility?

What technologies, design approaches, or criteria were used at the benchmark facility?

![]() How do the AV systems integrate with (or not integrate with) the facility’s IT network?

How do the AV systems integrate with (or not integrate with) the facility’s IT network?

![]() What are the benefits and drawbacks of the design approach taken?

What are the benefits and drawbacks of the design approach taken?

![]() What accommodations were made for upgrades and additions to the systems?

What accommodations were made for upgrades and additions to the systems?

Facility Management

![]() How does the benchmark facility organization manage its AV technology?

How does the benchmark facility organization manage its AV technology?

![]() How is the benchmark project serviced in terms of operations, maintenance, and help desk?

How is the benchmark project serviced in terms of operations, maintenance, and help desk?

![]() How much staffing is required to operate and manage the AV systems, and what are the qualifications of the staff members?

How much staffing is required to operate and manage the AV systems, and what are the qualifications of the staff members?

![]() What are the benefits or drawbacks of their technology management approach?

What are the benefits or drawbacks of their technology management approach?

![]() How do these approaches compare to the existing and/or planned facilities?

How do these approaches compare to the existing and/or planned facilities?

Owner and User Feedback

![]() What do the benchmark facility end users have to say about the technology and the facility?

What do the benchmark facility end users have to say about the technology and the facility?

![]() What do the benchmark facility technology managers and technicians have to say about it?

What do the benchmark facility technology managers and technicians have to say about it?

![]() What do the benchmark administrators have to say about it?

What do the benchmark administrators have to say about it?

Conclusions

![]() Which features of the benchmark facility should be included in your project design?

Which features of the benchmark facility should be included in your project design?

![]() Which features of the benchmark facility should be avoided in your project design?

Which features of the benchmark facility should be avoided in your project design?

![]() What aspects of the benchmark facility’s technology management approach should be developed or avoided in the current project owner’s organization, and what impact does that have on the facility and its systems?

What aspects of the benchmark facility’s technology management approach should be developed or avoided in the current project owner’s organization, and what impact does that have on the facility and its systems?

Obtaining Drawings of the Customer Space

In Chapter 12, you will examine further some of the standards and formats for site-plan documentation. Whether the facility you will be working on is already built or is being built, you will want to acquire drawings and drawing files of the space. For projects that are under construction, a range of documentation about the existing physical, organizational, and technical characteristics of the site should be available for review. If the AV systems are to be installed in an existing facility, inquire about drawings, and tour the area during the design process to document the physical aspects of the space and how it is currently being used.

Depending on the building system you want to understand, there may be several sources of documentation. Each of a building’s systems is defined by its own subset of drawings, but even those drawings may not include all the information you require, so it is important to work with building owners and/or architects and contractors to round up all the necessary information. A particular system’s functions are usually defined by discipline drawings, while the locations of system devices are shown on the architectural set of drawings. For example, the subset of drawings for an electrical system may define the electrical system itself, but not its physical relationship to the building. That information may be found in architectural drawings and would be important to the AV system design and installation. It is reasonably common that a single computer-aided drawing (CAD) format is used for an entire project. This enables all disciplines’ drawings to be imported and merged into a single multilayer file.

In addition, you will want drawings and information about so-called hidden systems, which may not strike other members of the project team as critical to the AV design but could actually play an important role in how AV systems will be installed or mounted on ceilings and walls. These hidden systems include structural, mechanical, fire protection, and others that an AV system designer and installer must consider when incorporating an AV system in the room. Figure 11-4 shows an example of a plan for speaker installation in a ceiling.

Figure 11-4 Plan for speaker installation within a ceiling

Ultimately, when locating an AV device based on information in architectural drawings, it is important to consider various elements and dimensions provided in the drawings. When examining drawings of a space, consider the following:

• Mechanical services drawings show the ductwork that goes through the building.

• Engineering drawings show the load-bearing and suspension points.

• Electrical drawings show locations of power and lighting.

• Engineering drawings show the location of communications and networking cabling, patch facilities, and distribution frames.

• Reflected ceiling plans depict the ceiling grid, diffusers, light fittings, sprinklers, projection system, and loudspeakers.

• Site drawings locate geographically where you will need to go to perform the installation.

The most important thing to remember is that you are seeking the fullest set of drawings available for the rooms that your AV design and installation tasks will address. And be sure to examine all of the elements that may potentially affect the layout, mounting, installation, and operation of the AV system components.

Obtaining Information About Constraints

When meeting with a client to collect general site information and information about the client’s needs, it is also important to learn about any issues or constraints that may impact your ability to work at the client site once the design and installation tasks begin. Here are some examples of constraints that may affect your ability to successfully complete work at the customer site:

• Limitations on times of day when on-site work is acceptable This could include restrictions on working in some areas during the day since your installation activities may adversely affect the ability of on-site staff members to accomplish their ongoing work.

• Limitations to on-site work activities For example, you may need to store equipment in backroom areas of a hotel to minimize the disruption that the installation tasks could present to guests.

• Security If you are working in a secure facility—for example, a government building—you may be required to obtain special identification to gain access to the facility. Certain facilities require even higher levels of security clearance. In most cases, you will not have won the job without demonstrating that you have or can obtain such clearances.

• Noise limitations Limits on noise in specific areas may affect what types of tasks you can perform at specific times of the day. For example, installation within a broadcast studio area may be limited to times when there are no scheduled broadcasts, or installation work within a cafeteria dining area may not be possible until after the lunchtime rush is over.

• Limitations on parking or loading vehicles These can be due to rush-hour parking restrictions on the streets surrounding the site or limited parking in the building parking lot.

• Areas that require special care or attention These areas might include rooms with expensive and fragile finishes or features, expensive artwork, or furnishings that must be protected. Note these types of issues, and work with the client to plan ahead to ensure that these items are safe and secure.

• Locations that present potentially dangerous conditions or require special procedures These might include areas within manufacturing facilities that may have hazardous conditions, such as moving equipment, the presence of flammable gases, or special electrical hazards. Such conditions should be noted, and any special procedures to follow when working at the site should be identified.

• Ongoing construction This may present a range of problems for an installation. For example, incomplete portions of the site might present dangers or prevent the installation from proceeding. Also, there may be conditions that can adversely impact the AV equipment, such as excessive dust or exposure to weather.

• Cultural issues These issues can affect how and when your team performs its work. For example, when conducting work activities within a religious institution, it is important to understand which days are considered non-work days for that religion. You should also be aware of any behavioral issues that may offend the adherents to the particular religion. Some areas and activities may require the attendance of staff of only one gender or require staff to wear a particular format of clothing. Language barriers are another potential issue at specific sites.

When collecting the client and site information, make sure that you note any of these types of issues and plan ahead to ensure that they do not adversely impact the design and installation tasks. In many cases, the team can identify a method to work around constraints, such as working during the evening or night in areas where daytime disruptions are prohibited.

Chapter Review

In this chapter, you examined gathering customer information. You can expect about six exam questions addressing the knowledge and skills related to material in this chapter. You should understand the following:

• How to communicate effectively with clients, from ascertaining contact information to ensuring you use the best communication medium in the best possible way

• How to obtain information about client needs, including specific AV-related tasks that the AV system should be designed to support—that is, defining the end users’ needs and using that information to determine the AV system functions necessary to address those needs

• Issues associated with obtaining drawings of the client space, including both existing spaces and any new buildings or rooms that remain to be completed

• What type of information you should collect on site-related constraints that may affect your ability to successfully complete the work at the client site, including the times of the day in which you are authorized to work at the site, any limitations on noise levels that could affect installation tasks, and cultural issues that you should be aware of when working at the site

Review Questions

The following review questions are not CTS exam questions, nor are they CTS practice exam questions. These questions may resemble questions that could appear on the CTS exam but may also cover material the exam does not. They are included here to help reinforce what you’ve learned in this chapter. See Appendix D for more information on how to access the online sample test questions.

1. Which of the following is not considered part of active listening?

A. Focusing on what the person is saying

B. Summarizing and paraphrasing the person’s statements

C. Asking frequent questions to guide the conversation to the topic you are interested in discussing

D. Maintaining eye contact with the person

2. What is usually the best approach for communicating detailed technical AV plan information to a client?

A. Sending the information within an e-mail message

B. Sending the client an electronic document containing the information

C. Sending a fax message

D. Calling the client on the phone

3. What is the most valuable source of information when defining the needs for an AV system?

A. Architectural drawings of the building

B. Feedback from benchmarking site visits

C. End-user descriptions of the tasks and applications the AV system will support

D. Client/building owner preferences for AV system equipment

4. What is the main purpose of an initial needs analysis?

A. To identify the specific equipment needs for the desired AV system

B. To determine the overall design of the AV system

C. To obtain the client’s vision of the AV system design

D. To identify the activities that the end users will perform and the functions that the AV system should provide to support these activities

5. How does knowledge of the overall room function assist the AV system designer in defining the client needs?

A. Provides a starting point from which to determine client needs

B. Defines the functionality that the system elements should provide

C. Provides a standard design that can be used for most clients

D. Provides a standard design template that can be given to the building architect

6. How are task parameters used when defining user needs?

A. To provide overall information about the desired general AV needs

B. To define the layout of AV components within a room

C. To define the specific AV functions that the components must support

D. To define the specific AV components

7. What is the purpose of benchmarking?

A. To demonstrate specific AV equipment in operation

B. To give the client an opportunity to experience a number of AV system designs that address similar needs

C. To test AV system designs

D. To evaluate AV vendors prior to final selection of a vendor

8. Why is it important for the AV professional to obtain a full set of building plans?

A. To understand the full range of room features to ensure that the AV system design takes other building systems and components into account.

B. To evaluate and approve plans to ensure that room elements are compatible with the AV system installation needs.

C. To be able to use general site plans to determine the layout of the selected AV components.

D. Detailed building plans for the rooms in which the systems will be installed are typically not required; only a general floor plan is necessary.

9. What client contact information should be collected during initial client meetings?

A. The main client contact

B. The client technical representative

C. Contacts that may be required for site inspection and installation, including the architect, building manager, construction manager, security manager, IT manager, and so on

D. All of the above

10. How does the AV team use information about any identified constraints to the AV design and installation tasks?

A. To select alternative AV system components that are not affected by the identified constraints

B. To inform the client that these constraints must be removed prior to installation tasks

C. To develop a work-around plan when these constraints will affect the design or installation tasks

D. To eliminate specific tasks that may be adversely impacted by constraints

Answers

1. C. Active listening includes focusing on what the person is saying, summarizing and paraphrasing the person’s statements, and maintaining eye contact with a person. It does not include asking frequent questions to guide the conversation to the topic you are interested in discussing, because the point of active listening is to actually hear what the client is trying to communicate.

2. B. Usually, the best approach for communicating detailed technical AV plan information to a client is to send the client an electronic document containing the information. Other methods, such as e-mail, text, messaging, or telephone conversations, are likely too informal to enable the client to review the detailed information.

3. C. The most valuable source of information when defining the needs for an AV system is usually end-user descriptions of the tasks and applications the AV system will support.

4. D. The main purpose of an initial needs analysis is to identify the activities that the end users will perform and the functions that the AV system should provide to support these activities.

5. A. Knowledge of the overall room function assists the AV system designer by providing a starting point from which to determine client needs.

6. A. Task parameters are used to provide overall information about the desired general AV needs.

7. B. The purpose of benchmarking is to give the client an opportunity to experience a number of AV system designs that address similar needs.

8. A. It is important for the AV vendor to obtain a full set of building plans because the AV designer must understand the full range of room features to ensure that the AV system design takes other building systems and components into account.

9. D. The AV team should collect the full range of client contact information, including the main client contact and the client technical representative. Also, the AV team should collect information about any contacts who may be required for site inspection and installation, including the architect, building manager, construction manager, security manager, IT manager, and so on.

10. C. The AV team uses information about any identified constraints to the AV design and installation tasks to develop a work-around plan when these constraints will affect the design or installation tasks.