Chapter 4. Innovation by Alliance: Reconsidering Innovation Collaboration

"[T]here have been dozens of consortiums that have come and gone in the past 30 years and there isn't a single one that has been successful."

—Palm Inc. Executive

Licensing wasn't the only way to expand the boundaries of innovation. For many R&D and commercialization purposes, alliances seemed a more promising and less passive option. Accordingly, the concept and practice of innovation collaboration expanded dramatically during the past decade. Alliances were offered as a solution to a host of emerging innovation challenges.[1] Basic research partnerships, as well as many other types of development-stage joint ventures and more encompassing and elaborate consortia, all grew in number and size.

At least three things were different about this innovation-by-alliance trend compared to the more established and traditional joint venture approach. First, collaboration increasingly became viewed as a critical way to accomplish more—and more basic—R&D tasks, as opposed to just later-stage commercialization such as manufacturing or marketing. Second, innovation alliances increasingly involved more and more collaborators—not just two JV partners—including complex mixes of private, public, and non-profit organizations. Related, and perhaps the most novel, was the New Economy notion that innovation by alliance was an increasingly essential strategy to succeed in the emerging "networked" economy.[2] The idea was that innovative firms in many sectors (especially high technology) no longer succeeded primarily on their own merits. Instead, innovators flourished or failed more and more as a function of the success of their alliance "webs," "networks," or "ecosystems," depending on the particular metaphor used.

The Perils of Partnering

As with most of the other innovation fads and fashions, there was more than a little substance behind the hype. But, much of the rush to find partners ignored the fact that, although alliances play an important role in the innovation mix, they have many limitations and drawbacks. They are intuitively appealing in the abstract, but have a much weaker and more complicated record in practice.

Whatever their benefits, innovation alliances involve a series of compromises and complexities that more tightly unified, integrated, and coordinated innovation approaches simply do not confront. Partnerships can impede quick and effective decision-making. They can be stunningly slow, inefficient, unfocused, and quarrelsome. Rather than help, alliances can actually impede development and commercialization. From Airbus to Sematech, Corning to Fuji Xerox, General Magic to Iridium and Symbian, some of the most celebrated examples of innovation collaboration have a mixed record at best.

Moreover, the role of some of the most important types of "new" innovation alliances often is not to give any particular firms competitive advantage or superior profitability. Instead, the goal is to help set a common context (for example, to create a "community" or set standards) for all stakeholders in a given new technology or market. Such collaboration might be necessary, but it is far from sufficient, for commercial success. Even when effective, most of the benefits of such open alliances usually go to customers or other stakeholders. They tend to produce great "public goods," not necessarily high private profits. Paradoxically, even as many network or ecosystem alliances flourish, companies are likely to watch rivalry intensify and profits wither.

Finally, whatever their usefulness, R&D partnerships and other forms of alliances cannot substitute for a firm's core innovation needs. Indeed, too much emphasis and investment in external collaboration can distract and detract from a more critical focus on core innovation. In a large number and wide variety of the cases we examined, this was an unfortunate byproduct of the alliance itself—regardless of its success (or, more often, failure). At their best, innovation alliances typically serve as a critical complement to core innovation, not as an alternative solution.

Collaboration Comes in Many Forms

The topic of innovation by alliance encompasses many different forms and functions, so the topic is difficult to quickly summarize or easily generalize. This section, therefore, focuses on the most important dimensions of innovation collaboration, including its most important uses and limitations in practice. Innovation alliances generally take one of these three forms:

-

Strategic alliances directly between two partners, typically focused on specific research, development, and/or commercialization objectives

-

Independent joint ventures or multiple-partner consortia, formally established as separate entities with their own charter and agendas

-

Looser and more open consortia or "network" alliances, often involving a large number and wide variety of private, public, and non-profit collaborators

With so many options and so many potential players, innovation by alliance can quickly become a complicated mix.

Collaborating to Compete

What motivated the increasingly urgent rush to find innovation partners? During the past decade, innovation alliances grew in number and variety for several key reasons. The changing nature of technology itself was a powerful driver of greater emphasis on innovation collaboration. Increasing technological complexity meant that no one firm could quickly and completely put together all the myriad pieces of a new product or service by itself. All kinds of newfangled hardware needed software, for example, and vice versa. Even the biggest firms needed assistance; they needed partners to help put all the pieces together into a workable (and marketable) package. In this sense, some of the same fundamental forces that pushed the growth of in-licensing and innovation by acquisition—such as technological complexity and time pressures—also pushed the trend toward more numerous and diverse innovation alliances.

In a similar fashion, soaring technological economies of scale (in R&D, manufacturing, and marketing) meant that larger required investments more frequently stretched any individual firm's resources, even industry leaders. The semiconductor industry exemplified this trend, as the necessary scale of chip-manufacturing foundries grew into the multiple billions of dollars per facility. Beyond the imposing scale of such investments, the more rapid and radical nature of technology shifts meant greater uncertainty and risk. Fewer firms were willing and able to take on the full share of such huge investment risks by themselves. Not only were the bets bigger, but the odds felt worse. Safety in numbers appeared to be a better gamble.

Under such challenging conditions, many firms found the potential benefits of innovation alliances irresistible. Innovation collaboration allowed two or more players to share the costs and split the risks. Two or more players could "synergize" and bring together their complementary strengths without having to unnecessarily waste money on duplicated and competing R&D efforts. Technology standards could be more quickly created and broadly established, greatly reducing uncertainty and rapidly expanding the entire market for new products and services. Innovation alliances brought together greater combined scale and strength, and more resources and capabilities than any one firm alone could hope to muster. All the partners could prosper. Intuitively, it just seemed to make sense.

Global Alliance Games

Along with these factors, globalization itself pressured domestic competitors to band together against perceived foreign foes. Governments began to encourage R&D collusion among competitors; even longstanding antitrust policies in the U.S. and Europe were waived. Policy makers gave their blessing and sometimes even direct financial support for these national "pride and protectionism" technology alliances. Sematech, for example, was founded and funded as a U.S.-centered industry/academic/government consortium that focused on developing cutting-edge semiconductor technologies. Sematech's goal was to help U.S. companies respond to what was perceived to be an immense threat from the rapid rise of the Japanese semiconductor industry in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Europe and Japan founded and funded a series of their own R&D consortia and even more extensive, fully developed innovation alliances. The pan-European Airbus consortium was one of the most successful examples. It had been formally founded many years earlier, but really took off in the 1990s. By the end of the decade, Airbus was not only the pioneer of numerous new aviation technologies, it also helped push U.S. firms Lockheed and McDonnell-Douglas out of the commercial aircraft business altogether. Airbus was aggressively innovating technologically and, in the marketplace, competed head-to-head with (if not besting) Boeing. With bold initiatives, such as the Super Jumbo aircraft, some even perceived Airbus as taking the lead. Boeing scrambled to keep pace.

Complex Lessons of Innovation Alliances

In a longer historical sense, innovation alliances were not entirely new by any means. Both R&D and commercialization joint ventures had a long and solid history that extends far before the recent wave of innovation mania peaked. A handful of historical examples had become quintessential success stories used to promote the great potential of innovation collaboration. Besides Sematech and Airbus, Corning and Fuji Xerox were two of the most prominent alliance exemplars.

During its long history, for example, Corning had repeatedly partnered its glass-working R&D and manufacturing expertise with numerous other companies. Corning founded a series of joint ventures, many of which became successful standalone companies such as Owens Corning and Dow Corning. Another classic and much cited example of innovation collaboration was Xerox's joint venture with Fuji Photo Film. Fuji Xerox evolved (even if largely unintentionally) from a simple Japan-focused manufacturing and marketing joint venture into a broad global alliance that served as a key source of improved technologies, products, and processes for its parent, Xerox. During the 1980s, Fuji Xerox's contributions helped generate higher quality and lower cost copiers and printers that allowed Xerox to compete more effectively with new and aggressive Japanese competitors.

However, in an often repeated pattern, even as the fashion for more and greater innovation alliances began to gather momentum, the exemplars of innovation collaboration already were seriously reconsidering their own strategies. Changing business and industry conditions, especially fast and focused new competitors, had rapidly altered the sense of their alliances. What had previously seemed like unassailable alliance advantages turned into handicaps and liabilities. Few seemed to notice or pay heed to these exemplars as they turned into glaring counterexamples.

As the 1990s drew on, Corning drastically simplified its widespread web of joint ventures, selling or spinning off multiple such operations in a bid to regain focus. Rather than muddling along as an ever-expanding network of increasingly diversified and scattered alliances, Corning strived to become a more tightly integrated company. The new Corning moved forward with a much more clear concentration on a few select high-technology sectors, such as fiber optics and liquid crystal displays. Its extensive network of alliances was dissolved.

Similarly, by the 1990s, Xerox's global alliance structure with Fuji Xerox and Rank Xerox (Europe) had become a significant hindrance. Xerox had too much duplication of R&D and manufacturing across North America, Asia, and Europe. The complex alliance structure saddled it with internal management squabbles, high costs, and slow product introduction. Xerox bought out and fully consolidated Rank Xerox, but it was too little, too late. By 2000, in a distressed effort to raise cash, Xerox was forced to sell controlling interest in Fuji Xerox to its Japanese partner, Fuji Photo Film, and give up the entire Asia-Pacific market. During all the complicated alliance restructuring, a lean, fast, and tightly focused Canon had supplanted Xerox's global leadership not just in copiers, but also in key growth sectors such as laser printers. Xerox retrenched and refocused on high-end corporate products and services in a bid for survival.

Corning and Xerox were far from alone. At the same time, the strategies of numerous other celebrated innovation alliances also were reconsidered and deconstructed. Despite its notable successes by the end of the 1990s, Airbus continued to struggle with its unwieldy structure of French, German, British, and Spanish partner companies, among others. Its market share success was not always matched by economic performance; its complex organization and inefficient operations remained subsidized in part through direct or indirect support from various interested European governments. To address these shortcomings, Airbus decided to completely reorganize itself from a loose European R&D and manufacturing consortium into a more closely coordinated and tightly unified competitor. Whither the alliance? By 2001, Airbus formally had become a single integrated company.

The experience of the Sematech consortium also offered mixed lessons. The U.S. semiconductor industry did regain global leadership from the Japanese during the 1990s. However, little of this was because of Sematech's direct contributions. Shortly after its founding, in fact, the founders and funders of Sematech realized that it would be too contentious for industry competitors to collaborate on developing new chips and chip technologies. Therefore, Sematech changed its charter to focus almost solely on improving semiconductor manufacturing processes. Meanwhile, following up on their great successes in the 1980s, most Japanese semiconductor leaders continued to heavily bet on further investment in memory chips. This strategy was soon imitated by the likes of other ambitious, up-and-coming Asian technology companies from Korea and Taiwan. Inevitable overcapacity in the memory market led to fierce competition and margin-slashing price wars. Whether by luck or by design, U.S. semiconductor makers had long since abandoned much of this now-commodity memory market; instead, they had switched to the design and manufacture of more complex, higher value-added microprocessors and specialty chips. This was a new "sweet spot" for the chip industry. Sematech's contributions, as much as they might have helped improve chip manufacturing, were clearly not what rekindled the leadership of U.S. semiconductor companies.

Nonetheless, long after their usefulness appeared to wane, these cases continued to be proposed as outstanding models and examples for innovation collaboration. The deeper irony, of course, is that these companies simultaneously were de-emphasizing or abandoning the alliance strategy for their own innovation needs. They already had reconsidered and revamped their own partnering strategies. In most cases, the complexities and difficulties of extensive collaboration had forced them to de-emphasize alliances and to pursue innovation closer to the central cores of their organizations.

Consortium Dysfunctions

Iridium was a shining example of the possibilities of innovation collaboration, one that unfortunately went bust. Much has been written about its ignoble failure. But most retrospectives focused on the symptoms of the failure instead of the root causes. At its heart, the Iridium experience illustrates the myriad potential problems of innovation alliances, especially more complex efforts involving multiple partners. In March 2000, even before the U.S. stock-market bubble imploded, few paid attention to the imminent collapse of Iridium's multibillion dollar satellite constellation. Iridium's high-flying global mobile communications dreams literally were set to crash to earth. The managing partner of the joint venture, Motorola, prepared to send 66 gleaming, brand-new satellites down to burn up in the earth's atmosphere. After spending more than $5 billion, Iridium was bankrupt, out of cash and out of time, unable even to pay basic operating costs to keep its satellite network in the sky.

This story began earlier in the decade, when Motorola formally announced the launching of Iridium. Over the next few years, Motorola formed a broad and deep-pocketed consortium to help fund Iridium and to develop both the necessary technologies and rich potential markets in literally every geographical region of the world. The audacious scale of the effort seemed to beg for a massive, groundbreaking global alliance. Iridium's promise was to develop and deploy mobile, handheld communications solutions to business customers who needed and demanded "anywhere, anytime" worldwide service. Using a globe-spanning satellite network, Iridium's handset would work equally well anywhere from Manhattan to Mount Everest. Customers would not be bound to local service providers and areas. They would not have to carry multiple phones to accommodate different country standards and service-provider technologies. There would be no frustrating and unpredictable service interruptions and no more "no signal" messages as they traveled around the world. Instead, customers would get seamless global service.

With Motorola as the lead managing partner and most prominent investor, the Iridium consortium took on a long list of other technology and telecommunications leaders as partners: Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Sprint, Bell Canada, Telecom Italia, and so on. Most of the partners, including Motorola, had a substantial interest in the venture outside of its own success: They either were suppliers of equipment or services or were resellers and marketers to Iridium's end users. It seemed like a win-win for all involved.

Motorola contributed the initial seed capital; technology planning and development proceeded methodically during the next couple of years. However, the major investments came with the actual construction and launch of the satellite network. To meet these immense capital needs, Iridium raised a total of $5 billion. The financing included equity investments from its partners, bank debt, high-yield bonds, vendor financing from equipment suppliers, and the proceeds of a partial $240 million IPO of Iridium World Communications. By 1997, Iridium was ready to launch its satellites and ambitiously announced that it would start service the next year. In an indisputably impressive technical achievement, its satellites were launched and the communications network was rapidly put into place in 1997 and early 1998.

After some embarrassing but relatively minor technical delays, Iridium launched commercial service in late 1998. Despite great fanfare and a massive and expensive marketing campaign to match, the service immediately sputtered. Customers balked at $3,000 phones and astronomical airtime charges of up to $7–9 or more per minute. Even with such a premium price tag, the phones and all the add-on equipment were derided as clunky and cumbersome. The phones did not work well in urban areas or in buildings, which are both serious problems if your key potential customers are traveling business executives. Meanwhile, even as Iridium was being built, tested, and launched, ground-based mobile telephony advanced by leaps and bounds. More mobile competitors were offering greater, increasingly seamless geographical coverage and new, higher quality services at prices lower than ever. Whatever Iridium's serious internal financial, operational, and marketing problems, the rapid technological and competitive evolution of the entire mobile communications sector only exacerbated its difficulties. In August 1999, less than a year after commencing operations, Iridium defaulted on $1.5 billion in loans and filed for bankruptcy.

Requiem for Iridium

Many different analyses of Iridium's failure have been offered. Was it just part of the insane boom and bust of the entire telecom sector? Perhaps in some larger sense. But, the fact is that Iridium's build out, and then its bankruptcy, occurred long before the larger telecom boom even peaked, much less crashed. Most diagnoses have instead focused on the factors previously discussed: high prices, clunky phones, poor service, and so on. The problem with focusing on these factors is that they are symptoms rather than root causes.

The root cause of Iridium's difficulties might better be traced to the very nature and structure of the innovation alliance itself. Iridium was a consortium with many inherent conflicts and handicaps. One account noted that Iridium's partner board meetings often seemed like a mini–United Nations gathering, with headsets for translating the proceedings into five different languages.[3] With so many different partners involved, no one party had adequate perspective, sufficient incentive, or enough power to recognize the need for and to make meaningful changes to Iridium's strategy and its implementation at critical junctures. Many specific technical and market concerns were voiced, from both inside and outside, as the venture progressed. However, no single partner had the perspective, incentive, or power to alter the consortium's course until it was too late. Iridium had a momentum all its own. This inertia made it difficult to sense and react to all the warning signals at numerous points along the way.

Making matters worse was that several of the Iridium consortium's key players had conflicting interests, which is typical of so many joint ventures and alliances. Although it was the lead partner and key investor, Motorola's interests and Iridium's interests were frequently not aligned. In Iridium, Motorola had a lucrative and captive customer: It made and sold equipment to the venture under a 5-year, $3.4 billion design-build-launch contract. Curiously, at one point in 1997, Motorola boosted its guarantees of the Iridium consortium's bank loans (to $1.1 billion) so that Iridium could raise the cash it needed to buy satellites from . . . Motorola. Unfortunately, the satellites were far from ideal. They could handle only a relatively small number of calls simultaneously, which greatly limited the network's scalability and dramatically raised its call costs. Motorola also had a multiyear, $3 billion service contract to operate the Iridium network after it was up and running. These high fixed operating costs later became enormous financial baggage for Iridium and a fierce point of contention in its slide toward bankruptcy.[4] Motorola further took the lead on designing and manufacturing the handset equipment it then sold to Iridium. The clunkiness and glitches of its handset equipment quickly gained notoriety.

The bottom line is that, in many joint ventures and alliances, even collaborators with the best intentions can easily become less focused on ensuring the overall success of the partnership and more concerned with carving out their own slice of the pie, even before it's half baked. Motorola's self-dealing contracts with Iridium looked like a logical win-win in the short-term, even for some of the other partners. However, these agreements were a fateful handicap. They severely limited Iridium's strategic options and its financial, technological, and operational flexibility. The Iridium alliance was fatefully handicapped from its inception.

Risk Comes in Many Different Forms

Despite all its travails, Iridium nonetheless could be viewed as a "success" in the sense that it did limit the risks for its participants. For each major partner and investor, especially Motorola, the use of an alliance structure capped the potential losses for any one partner from investing in a bold and risky new idea. This is certainly true in a narrowly defined sense. No one partner had to bear the full force of the multibillion dollar loss when Iridium filed for bankruptcy. On the other hand, this very sense of limited risk enticed both partners and investors to push ahead with a venture that otherwise, quite literally, should never have gotten off the ground. A false sense of safety in numbers—especially because of the blue-chip pedigree of the key collaborators—lured partners and investors to suspend their often well-justified concerns and pour in more cash.

The risk-spreading nature of alliances can lead to collective overconfidence that causes collaborators to push forward with ventures that have questionable business cases and weak risk/reward profiles. The problem is that alliances fundamentally do not eliminate the technological and market risks of innovation. The overall risk remains just as large and real. By parceling it out, however, the risk seems less to all involved, even though the overall odds are no better. In contrast, when a single company has to make more stark and consequential investment choices at each stage of development, it is forced to deal with the total picture of risk. With less perceived threat and with the (false?) confidence of collective clout, Iridium moved forward despite continued doubts and uncertainties about its viability. The partnership had not, in some magical way, reduced or eliminated the real total risk.

Risk is also a multifaceted concept. The real, substantial, longer-term risks of innovation are often less overt and more hidden or subtle. It is true that the financial structure of Iridium limited Motorola's direct losses to only a fraction of the $5 billion invested. Some even claimed that Motorola won from the entire affair despite Iridium's failure because of all the rich contracts and technology Motorola gained from its involvement. Still, although Motorola had just 18 percent of the equity, its complex financial relationship with Iridium made it responsible for more than $2.5 billion in losses and write downs. Banks and bondholders later sued Motorola for $800 million and $3.5 billion, respectively, for its role in Iridium's downfall, though the company got away with paying just a fraction of those claims.

Regardless of these significant and disproportionate direct losses, focusing only on the immediate financial impact misses much of the larger, more important story. The entire Iridium adventure had a more insidious impact. While wrapped in the complexities of developing and launching (and then trying desperately to rescue) Iridium, Motorola made a series of missteps in its core cell-phone business. It dragged and delayed on the switch from analog to digital equipment. It fell behind in introducing new styles and new features. In short, Motorola slipped and then lost its previously unrivaled global leadership in the cell-phone industry. By 1998, the year Iridium was launched, Nokia just narrowly surpassed Motorola in terms of global market share. By 2000, Nokia had twice the global market share of Motorola.

It's difficult to assign precise blame for these strategic stumbles in Motorola's core business. But, its Iridium misadventures were a critical diversion, to say the least. Undue reliance or emphasis on joint ventures and alliances can detract and distract a company from core innovation. The Iridium saga was not just a harbinger of larger problems for Motorola; it indirectly may have been the largest single cause.

Joint ventures and alliances, rather than being quick and synergistic ways to develop and introduce new technologies, products, and services to market, often instead are cumbersome, slow, and rigid. By their very nature and structure, they tend to be conflicted, unresponsive, and inefficient. The potential for problems grows as does the number of players involved. Instead of managing risk better, alliances can actually increase risk taking. By joining together, partners might be lured into a false sense of security as they collaborate to advance ideas with a poor risk/reward profile, ideas that they never would have chosen to pursue individually. Alliances do not get rid of undue risks; they only spread the risk around without bettering the overall odds. The likelihood of failure can actually increase as partner tensions and conflicts arise and as dysfunction and paralysis ensue.

All these points were true in the case of Iridium. Consortium dysfunction was the fundamental cause of its failure. All these issues are especially crippling problems in fast and radically changing industries, as is the case with much of high technology innovation. When considering alternatives, it's important to remember that these are problems not engendered by more tightly unified, integrated, and coordinated approaches to innovation.

The Attraction of Open Innovation Collaboration

Even with many more collaborators, however, more open and inclusive innovation alliances can be surprisingly functional and fruitful because in many ways they offer a lot more flexibility than formal joint ventures or consortia. Rather than build a two-partner or multipartner joint venture, open and networked forms of innovation collaboration involve building a fertile community or ecosystem in which a particular innovation can flourish. Such widespread cooperation has been absolutely essential to advancing R&D and commercialization in a wide variety of technologies and industries: to set standards, to ensure interoperability of hardware and software, even to generate whole new classes of products or services. Through open, active, and enthusiastic collaboration among many different stakeholders, innovation advances and enormous value is created.

The basic logic is that some innovation collaborations make greatest sense with more players in the game. This theory caught on during the innovation boom in various guises: "co-opetition," "positive feedback," "network externalities," and the like. More partners is better; the more players in your "network" or "web," the merrier. The reasoning was that the more allies (especially customers and providers of complementary goods and services, but also even including competitors), the more likely your own offerings would flourish. The bigger and more inclusive the network, the more the entire ecosystem prospers, which creates a rising tide.

The profitability paradox in this expansive and open collaboration model arises from the fact that creating a rising tide for all advantages no single company in the core market. Enormous benefits can be created in a holistic sense. But, unless a specific company somehow has privileged or proprietary control of the playing field, most of the benefits of innovation go to consumers or to providers of complementary goods and services, not to competitors in the core market. In fact, for companies in the core market, free and open collaboration tends to lead to freer and fiercer competition. Rivalry ultimately tends to increase and profits tend to drop considerably. Most created value does not directly flow to the bottom line of any company in the core market; instead, it is captured by other stakeholders.

These types of alliances, therefore, might be a fantastically positive proposition for technology and society as a whole. For profit-seeking innovators, however, the dynamics of such broader collaboration create a serious challenge. There are good, natural reasons why most "standard setters" are organized as non-profit or not-for-profit entities (such as IEEE and ISO). Similarly, it's not just coincidence that some of the most flourishing examples of open and networked innovation collaboration foster relatively modest or meager profits; it's inherent to the form. In recent years, Linux has been the most popular and influential case in point.

Free and Open Software

Like so many other exemplars of innovation, Linux quickly became the stuff of technology legend, even long before it had been established—much less victorious—in the marketplace. Because it was such a compelling story, the excitement and hype predictably outpaced the reality. By the late 1990s, competitors and customers badly craved an alternative to Microsoft's pricey supremacy. Linux was enthusiastically embraced when it first appeared on the scene, even though (in part because) it was a relatively radical and unproven departure from the dominant proprietary software model.

Linus Torvalds was storied as the freethinking founder and original programmer of Linux. In 2000, however, the founding of Open Source Development Labs (OSDL) brought Linux to an entirely new level. The founding members included undisputed technology heavyweights like IBM, HP, Computer Associates, Intel, and NEC; many other leading-technology companies soon joined the bandwagon. OSDL formed as a non-profit organization with the express purpose of supporting and promoting the further development and adoption of Linux.

Never it seemed had Microsoft faced so credible a threat. During the prior decade, Microsoft's grip on the software industry had expanded beyond desktop PC operating systems, to PC applications, to web browsers and the Internet, then to server and enterprise operating systems and applications. Previous attempts to weaken Microsoft's growing domination proved spectacularly unsuccessful as it methodically crushed even much faster, more nimble and innovative, and technologically superior competitors (think Netscape, among many others). Its dominance had grown so thorough that antitrust action against Microsoft seemed many would-be competitors' last resort. They banded together to support U.S. and European action against the company. Even the respective governments' punitive findings against Microsoft proved relatively ineffective at denting its immense power.

Beyond the general craving for any credible (and more affordable) alternative to Microsoft, Linux generated excitement for numerous other reasons. Shareware, open-source, and other such "enlightened" collaboration had long been practice among the techsavvy. The Apache Software Foundation's open-source programs scored a big hit for web servers, for example, quickly capturing a large share of the server market. For broader commercial applications and the mass user market, however, Linux was still a novel concept. It offered threats to Microsoft's software dominance across the board—from the enterprise to the home, from the server to the desktop to the mobile phone.

Linux was not just another company. It was a thriving community. That was precisely its power. It was an open-ended, open-source innovation alliance. That is, unlike Microsoft's proprietary, "secret-source" code, Linux was an open book. Unlike with Microsoft products, Linux users could freely see and explore, alter and improve, the underlying computer code. They could customize and optimize it. In turn, by agreement, users openly shared their inventions and improvements with the larger Linux community.

Linux offered the networked power of a global, non-stop innovation factory, with thousands upon thousands of users and programmers from all over the world sharing in the discovery and the benefits. Linux started to gain traction first in server and enterprise operations, but other applications soon followed. Governments around the world, from Asia to Europe to Latin America, started to openly embrace and promote Linux as an attractive alternative to paying rich tribute to Microsoft, the arrogant U.S.–based software colossus. Beyond its business impact, Linux was a great technological and sociological story, with instant appeal.

Higher Market Share = Lower Profits

In all the excitement, some of the key implications of the Linux movement got lost, at least initially. Looking for a new hot company and the next big thing, entrepreneurs and executives, analysts and investors, paid scant attention to the fact that, even if Linux took off and perhaps even eventually trounced Microsoft, the "next Microsoft" could never emerge from the Linux movement inherently because of the very nature and structure of the collaboration. Nonetheless, the shares of the leading Linux software and hardware plays, Red Hat and VA Linux, were bid up as if they might actually have a serious shot at being the next Microsoft. In fact, VA Linux set an all-time IPO record with a 700-percent first-day leap in its stock price.

Even at the time, some observers noted the yawning discrepancy between the Linux hype versus the basic economics of the companies' actual business models:

Linux is the operating-system software that is a growing threat to Microsoft. The many Linux companies that have cropped up in the past few years seem to have a lot going for them. These include marketplace momentum, a loud buzz, and—in the case of Red Hat Software—a multibillion-dollar initial public offering that has numerous other Linux start-ups scrambling to go public, too. There's just one hitch: The Linux operating system can also be had free of charge, downloaded off the Internet.[5]

The business models of the Linux players offered not secret, tightly controlled, and highly profitable software, as did Microsoft. They inherently could not have a monopoly as did Microsoft. Instead, they proposed to make their mark and their money not from the base software but by offering upgrades and add-ons, service and support—or even by making and selling Linux-running hardware.

The excitement over Linux did not die with the deflation of the dot-coms. By 2003, Linux started to become a serious competitor to Microsoft, especially in the server market. And Red Hat remained the dominant name in the Linux world. But the much less lucrative economics of the open-source model, versus Microsoft's proprietary offerings, remained a problem. In January 2004, Barron's skeptically noted that continued optimism gave Red Hat a market capitalization of $3.5 billion, which was larger than the entire Linux market. Despite being the leading name in Linux, Red Hat had quarterly revenues of just $33 million and continued to run losses. This compared with revenue of more than $2 billion for Microsoft's "server and tools" division alone. Linux was a great new thing, offered Microsoft its most serious competition in years, and promised even greater innovations ahead. But this would not readily and easily translate into rich profits for its purveyors.

To Linux skeptics, the fact remained that Microsoft reaped its rich profits by avoiding and taking advantage of, not by joining in, the open-architectures and common-standards of the PC industry. After standards emerged, the PC hardware industry itself quickly became one of the most fiercely competitive and thinnest margin businesses, leaving many failed companies in its wake and even causing the standards' originator—IBM—to exit the retail-consumer PC business altogether. Of the major players, soon only Dell managed to eke out a profitable and sustainable position, and only then by being relentlessly hyper-efficient in a bid to combat the inexorable margin squeeze of an industry with ever more commodity-like economics. A similar cycle would soon take hold in many other areas of computing and communications.

Linux won more and more share, especially globally. Compared to the game Microsoft continued to play, however, Linux was a game with dramatically reduced revenue potential and even more shrunken margins. Even if it ended up being an even larger pie overall, most of the value was sliced up and given away to other stakeholders. The model was to charge for service, support, and hardware for core products that nominally were free or low-cost, open-source or standardized. To pursue "razor economics," the concept went: Give the razor away and make a mint on selling the blades. The problem is that the clever-sounding theory and the rich potential of "razor economics" only works well when the blades are proprietary. In contrast, Red Hat honestly disclosed:

Open source software does not mean free as in without cost—but open source does mean that the software is free (as in freedom), meaning no one company can fully own and conceal it. Software lock-in is impossible...Will it be as financially lucrative as a software monopoly? No. Will customers more appreciate and realize its value, and therefore become better customers? Absolutely.

The problem is not one of creating value. Such open alliances can be fantastically powerful for creating it. Instead, the issue is how to capture enough of a share of the value created to devise a workable business model, sustain a company, and earn a decent return on capital. In the aftermath of the initial Linux hype, the companies best poised to capitalize on its success ironically were those who had the strongest ongoing, internal, and proprietary innovation efforts—especially including many established technology hardware, software, and services leaders (such as IBM), but often less so of many of the Linux upstarts.

The Java Community

Sun's Java experience shows how difficult it can be to foster a thriving innovation network, and yet somehow still profit handsomely through a privileged position in that network. In 1995, Sun released Java to much acclaim as alternative (to Microsoft) code upon which to build the software of the future. Java's key attraction was that it was open-source code, freely posted and available for individual use. Adaptation of Java for mass commercial purposes, however, required Sun's approval of any changes and additions; this ostensibly assured the quality and compatibility of all Java programs. Commercial use of Java also required payment of modest (at least in Sun's view) licensing royalties. Despite the initial fanfare, Java got off to a slow start. Users complained about Sun's paternalistic control and its royalty charges.

In response, Sun loosened both. Both Java applets (small, embedded applications) and their developers and users began to multiply. With the explosion of the web and other new applications, such as mobile phones, a substantial Java community emerged. As the Java movement grew, Sun repeatedly squelched rumors that it would jack up its licensing fees to make Java more profitable. Sun publicly re-emphasized its original strategy: to broadly encourage Java development in order to help sell the company's larger hardware and systems. A disconnect existed, however. Nearly a decade after founding Java and despite a flourishing Java community, Sun captured only a small portion of the value created by the innovations it had pioneered, even as it continued to struggle with its core proprietary hardware businesses.

Capturing Value from Open Alliances

As the evolution of Linux and similar innovation alliances show, open and inclusive collaboration can work extremely well for accelerating R&D and fostering wide commercialization. In fact, such alliances are increasingly essential, not optional, as everything literally becomes more networked. Despite being effective for such broader purposes, by its very nature open innovation collaboration does not give competitive advantage or superior profitability to any one collaborator. Broad, diverse, and open innovation alliances therefore may be absolutely essential precursors to building a new technological or market playing field rich with possibilities. But even when these alliances are fantastically successful, by themselves they do not offer a clear path to superior profits for any particular player.

Encouraging open innovation alliances therefore may make good social and public policy. Overall public welfare benefits, even if often at the expense of profitability among competitors in the core market. Customers reap the benefits of many different competitors pushing interoperable and interchangeable products and services, typically with ever-greater features and ever-lower prices. The functionality of the core offering becomes more of a commodity. Prices and profits are pushed down even as volumes increase and ever more value is created.

The bottom line is that open-network alliances do foster innovation and can create enormous "spillover" benefits. Even so, they cannot serve as the centerpiece of a successful firm-level innovation strategy. As much as they might want or need to support such extensive collaboration, profit-seeking companies must pursue innovation strategies with their own distinct and proprietary paths to profit. This remains the key challenge, despite the undeniable potential of open network alliances. This is the job of a core innovation strategy.

Of course, having a thriving and expansive but proprietary alliance network could offer unparalleled profit potential for the firm that's at the center of it all. But there's obviously no good reason for anyone else to join such a domineered network—unless they're coaxed or coerced, that is. In practice, therefore, these types of "dominant player" webs or ecosystems represent not alliances so much as follow-the-leader supremacy of one central firm typically because of its own extraordinary technological and/or market leadership. An ecosystem grows to enhance and perpetuate this advantage, but the impetus for the thriving network in the first place comes from the dominant firm's powerful core investments in developing and commercializing innovation (such as the frequently used example of Microsoft in software, and any number of other computing and communications leaders, Wal-Mart in retail, and so on). Everyone wants to "partner" with a winner. The dominant firm's technology and market leadership is more often the foundation and focal point of a rich network of partners and other complementors—not the result of it. Overemphasizing the network itself misses this key point and confuses cause with effect.

The Elusive Symbiosis of Innovation Alliances

The story of Symbian showcases the range of different approaches toward innovation alliances: the proprietary approach (Microsoft), the joint venture or consortium approach (Nokia, et al.), and the open-network alliance approach (Linux). Symbian was a consortium formed to provide operating systems and other types of software for mobile phones. It's a case that illustrates well the relative advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches to innovation collaboration that we have discussed so far. Should we go it alone? Should we use joint venture or consortium? Or should we participate in and use an open-network alliance?

As mobile phones grew more complex toward the decade's close, with greater functions and more features, communications and computing began to meld. Mobile phones were trending toward wireless, networked computers: personal digital assistants, web surfers, e-commerce platforms, and more. They would need increasingly sophisticated software to smoothly perform all these functions. They needed powerful but "lite" operating systems. Nokia, Motorola, and a host of other major mobile phone makers had previously performed most of this software work in house. But, with mobile phones morphing into computers, the major manufacturers began to look elsewhere for greater software expertise and solutions.

Microsoft was more than happy to oblige. Having conquered so many other realms, Microsoft made a big push into this new and unconquered territory. The software behemoth began aggressively promoting its own mobile, portable versions of Windows for mobile computing and communications. But, the last thing many of the mobile-phone majors wanted to see was another Microsoft-dominated software monopoly in mobile communications. At first, they resisted. Then, they responded with a powerful alliance.

In June 1998, Symbian was incorporated as an independent company, a for-profit consortium of most of the major mobile phone makers, led by Nokia, and Psion, a U.K.–based leader in mobile computing hardware and software. Ericsson, Matsushita, Motorola, Samsung, Siemens, and others joined in the effort. Each of the major partners was also a major shareholder. All pledged to use Symbian operating systems and software in their next generation of more advanced mobile phones. It was an attractive alternative to being a captive, tribute-paying customer of another Microsoft monopoly.

As a distinct joint venture, Symbian could focus on the software while the mobile-phone makers could continue to focus on their hardware competencies. Together, Symbian's partners represented more than 80 percent of the global handset volume. Their combined efforts would be better, quicker, and stronger; all would gain from the success of the joint venture, from both the software directly and from their equity stakes as it grew. The plan even included hopes for Symbian to perhaps eventually go public. With Psion's software expertise at its core and with so many strong partners involved, the consortium appeared to be off to a great start. Even outside the alliance, many cheered it on. By 2000, the perception was that Symbian was in the lead in developing software for mobile-communications software. Microsoft appeared a weak also-ran, with slow, clunky, and power-hungry offerings.

Despite this strong head start, the nagging fact was that most of Symbian's partners and shareholders remained fierce competitors in the global mobile-handset market. It was an uneasy alliance from the start. Even before Symbian introduced its first product, Nokia was signing separate deals to use software from Palm, the handheld computing leader; Ericsson inked a deal with Microsoft; and other partners openly considered other software options. In mid 2000, one of the key founders and executives of Symbian suddenly left to join Microsoft's mobile software efforts, which lead the consortium to threaten legal action.

Even with this turmoil, Symbian did manage to beat Microsoft to market with its June 2001 software release as part of a new, advanced Nokia phone. But also in 2001, Nokia announced the formation of its own new division, Nokia Mobile Software, to create and license its own mobile software solutions. Meanwhile, Microsoft added a new twist, revealing plans to help foster more standardized and simplified mobile phone architectures to allow new upstart hardware manufacturers to enter the mobile-phone manufacturing game.

Tensions that had been privately bubbling came publicly to the surface as soon as a five-year standstill agreement among Symbian's partners neared expiration. In early 2003, Motorola announced plans for a new advanced phone based on open-source Linux and Java software. Motorola later dumped its entire Symbian stake, left the consortium, and just a few weeks later, announced a new Microsoft Windows–based Smartphone.

Putting the consortium on even more uncertain footing, in early 2004, Psion also sold its entire stake in Symbian. With Nokia as the primary potential buyer, the consortium was poised to become, for good or bad, a de facto Nokia subsidiary. Many observers openly wondered why and whether the other mobile-phone makers who still were part of Symbian would continue to buy operating systems and software from an effective subsidiary of their biggest competitor, Nokia. Why should they not opt for Microsoft or Linux and Java solutions instead? What had seemed to be such a bright future for Symbian was now much in doubt. It was threatened by the unified Microsoft juggernaut on one side and by the relatively free-form, open-source options of Linux and Java on the other side, even as it tried to juggle its own internal consortium discord. On the other hand, at least if Nokia now took more clear and focused leadership of the group, perhaps Symbian might actually have a better chance.

Mobile Computing Redux

To many involved in the computing and communications worlds, Symbian's storyline seems at least vaguely familiar. Wasn't it just a few years earlier that General Magic, the mobile-computing operating systems and software consortium, had garnered even greater excitement and support? In the end, none of its partners were able to use its fruits to succeed in the mobile-computing space. General Magic itself flailed for years and finally folded.

The goal of General Magic and its partners was to come up with the next generation of operating systems and software needed to make mobile computing possible, to take personal computing away from bulky desktops and laptops and make it truly portable. Apple was the genesis of the effort, which began in the early 1990s. However, soon General Magic became one of the most heralded technology consortia in memory, as some of the biggest and best names in communications and computing joined Apple as partners and investors.

Many key names that hopped on the General Magic bandwagon were the same names that, a few years later, were to back Symbian. Motorola, Sony, AT&T, Matsushita, and Phillips were early partners, and other blue-chip names, like NTT, Matsushita, and Toshiba, soon followed. With such powerful backing, General Magic was as close to a sure bet as one could imagine in the risky and uncertain world of high technology. Following this logic, the company even managed to launch a successful IPO in 1995, even though it had no product or revenue yet.

General Magic eventually did launch several versions of its much anticipated software during the next few years. But neither the software nor any of its partners' hardware managed to survive—much less thrive—in the mobile computing marketplace. From Apple's Newton to AT&T's EO to Motorola's Envoy (among others), each failed to gain traction and folded. General Magic itself was left to scramble for a new mission and market. After several years of futile strategic flip-flops, General Magic finally shut its doors. Meanwhile, a more focused and patient Palm, Inc., followed by the methodical and inexorable efforts of Microsoft, gradually took leadership of the mobile computing operating systems and software sector.

Joint Venturing Lessons Learned

The sagas of Iridium, Symbian, and General Magic emphasize the sketchy record of using independent joint ventures or consortia to drive key innovations. No matter how strong the partners, the joint ventures themselves often lack focus and direction. They suffer from inherent tensions and conflicts. They engender dysfunction and paralysis by trying to serve the ends of many different masters, including themselves; in turn, they often end up pleasing no one. They might endure either the neglect or the competitive antagonism of their partners, or both. Joint ventures themselves can even become serious competitors to one or more of their parents, or vice versa.

Sometimes, circumstances make such joint ventures an unavoidable choice. If so, due diligence is essential. They should be carefully structured to align each party's interests and incentives, including those of the joint venture itself. They must have clear objectives and boundaries, including especially vis-à-vis the parents. They must have clear mechanisms for dispute resolution and alteration of the terms of the original joint venture agreement, and clear mechanisms for termination and dissolution after the joint venture outlives its usefulness. Of course, with all these diligent restrictions and well-intentioned limitations in place, it's easy to see why innovation alliances so often fail at their assigned tasks: They tend to be inherently constricted from the get-go.

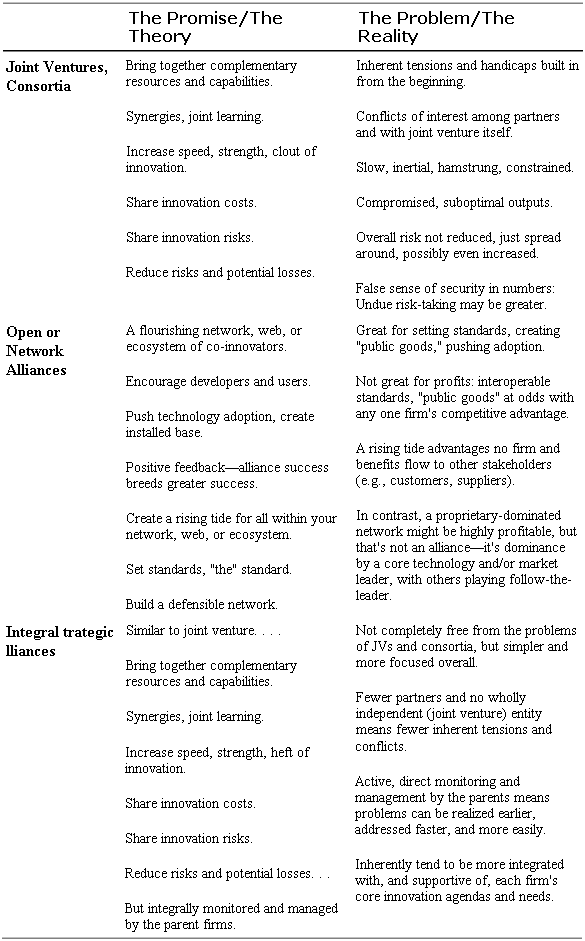

Joint ventures present inherent tensions and compromises under even the best of circumstances and with the most amiable of partners. They labor under special burdens. Ideally, therefore, the problems of core innovation are best not left in the charge of separate joint ventures or quasi-independent consortia. Nor, ideally, should a core innovation strategy depend on loose and open alliances (see Table 4-1).

Table 4-1. Innovative Alliances or Joint Problems?

With all these caveats, it's important to reiterate that many desirable or necessary but non-core (peripheral or complementary) innovations often are best pursued either through dedicated joint ventures or looser, more open alliances. Quite simply, if the needs are non-core, consider an alliance. Open alliances well serve goals such as helping set new standards. Dedicated joint ventures, on the other hand, can be used to help ensure critical supplies and suppliers, necessary but novel manufacturing technologies or production capacity, and so on—especially in the absence of feasible alternative market mechanisms. In the semiconductor industry, for example, the huge scale of chip plants requires manufacturing collaboration among competitors, customers, and suppliers. Also, in the semiconductor industry, the Sematech consortium did help the U.S. semiconductor industry devise complementary advances in manufacturing processes. These types of innovation needs frequently lend themselves to collaborative arrangements rather than internalization. Moreover, joint ventures also can be effectively used as part of a process to spin out and thereby externalize, yet still profit from, non-core innovations (Chapter 6). Using collaboration for such peripheral or complementary tasks can enable a company to keep a keener focus on its own core innovation, even while helping create a more favorable overall context for value creation and capture.

Toward More Focused Innovation Alliances

Despite all the potential pitfalls of innovation collaboration, it can be enormously productive and profitable even for core innovation tasks. But such alliances most often are best kept tightly integrated, monitored, and controlled, not set loose with a life and a will of their own. This is our conclusion after thoroughly reviewing more than 100 different forms and types of innovation alliances in a wide variety of industries. The one form of alliance we have not yet discussed—strategic alliances directly between partners, typically focused on specific research, development, and commercialization objectives—is frequently the most efficient and effective means of innovation collaboration. By this, we mean clearly targeted alliances that are created, monitored, and managed directly between the parent partners. Often there is no independent entity with its own charter and agenda or, if so, it might be a function of legal requirements and other formalities, more than by strategic need or organiza tional design.

Such alliances are increasingly common in technology-intensive sectors, but they run the gamut. Starbucks and PepsiCo were successful with their North American Coffee Partnership (NACP), for example, starting in 1995. NACP was formed to produce and sell ready-to-drink, bottled coffee products (for example, shelf-stable Starbucks Frappuccino) through a variety of retail outlets. It was a modest commercialization joint venture in many senses. But it succeeded notably where others had failed, including giants Kraft and Nestle. Some of the reasons for its success were basic. The joint venture brought together the complementary assets of Starbucks, the most recognized name in premium coffee beverages, with Pepsi and its powerful distribution network, finely-tuned to push bottled beverages through innumerable and diverse retail channels.

The reasons for NACP's success also were as much due to the underlying logic and structure of the alliance itself. The parent companies, Starbucks and Pepsi, were not competitors in any significantly direct sense. The joint venture had very clear and simple and focused objectives—producing and pushing ready-to-drink, bottled coffee products through retail channels such as grocery and convenience stores. Another key success factor was that, whatever the novelty of the product, the joint venture did not involve a critical product for either partner. Starbucks remained centered around delivering "the coffee experience," crafting and serving espresso drinks to customers in its own barista-staffed cafés. For Pepsi, ready-to-drink coffee was not a "killer category" like its other core beverage offerings (e.g., carbonated soft drinks). Even this successful example therefore shows how joint venturing often is relatively more fitting for the tasks of complementary, but relatively non-core, innovation.

Higher Stakes, More Potential Problems

Disney's lucrative partnership with Pixar shows that alliances for the purpose of core innovation tend to be more problematic. The stakes simply are higher. Animated films, from Snow White to The Lion King, were the heart and history of Disney's success. Following Disney's The Lion King blockbuster in 1994, it became clear that animation was evolving from the old hand-drawn labor of love into a new type of digital artistry. Disney had little competence in such hi-tech wizardry. Pixar, the computer animation company led by Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, became Disney's entry into the digital age. Pixar provided the hi-tech expertise to create the films, while Disney co-financed and distributed them.

Disney-Pixar seemed like a very powerful and complementary pairing. Indeed, it was. Beginning with Toy Story in 1995, the Disney-Pixar partnership produced a series of hugely successful films (including A Bug's Life and Monsters, Inc.). Indeed, Disney-Pixar's 2003 release Finding Nemo was the highest grossing animated film ever. By 2004, the partnership's films had generated more than $2.5 billion in box-office sales alone—not to mention videos, merchandise, and everything else.

But success caused friction. With the ten-year relationship up for renegotiation, the partners clashed over management, artistic control, and profits. Pixar demanded more of all three. Disney balked, and Pixar walked. Disney faced losing a future stream of digital blockbusters, even as its own internally produced animated films had increasingly disappointed fans and investors alike (for example, the massive flop Treasure Planet in late 2002).

Had Disney's success with Pixar lulled it into complacence? Now, Pixar was poised to be a powerful competitor, even as Disney's own digital capabilities remained limited. Meanwhile, Disney had slashed its animation division and, even according to namesake nephew Roy Disney, lost much of its creative edge. Disney's traditional animation core looked weak, and its digital future uncertain. Refurbishing the Disney legacy for the digital age would take significant cash and toil.

Pursuing Direct, Active, Engaged Partnerships

Despite such common tensions, close and focused collaboration nonetheless can make compelling sense for the tasks of core innovation. The biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries provide key examples. The usual scenario, of course, is that a small startup links its scientific discovery and promising new compounds with the cash and muscle of a big pharmaceutical company. The startups have the basic ideas and the big partners have the resources and capabilities needed to push investigational new drugs all the way through final clinical trials and out into the marketplace. A drug-licensing deal is often the result. As with other such integral alliances, there often is no formal third-party entity to complicate matters (such as a joint venture or consortium itself). Instead, the partnership directly brings together complementary assets and roles that are closely monitored and actively managed by both partners. The joint venture does not have a life and mind of its own. These types of alliances are not without their own difficulties. But with a relatively simplified structure and organization, and active ongoing management, problems can be more readily recognized and more quickly resolved.

The partnership of Trimeris, a small biotechnology company, and Roche, the large European-based pharmaceutical company, provides a good example of such integral innovation collaboration. In 1999, Trimeris and Roche agreed to cooperate to bring to market a new class of therapies for drug-resistant HIV strains. Unlike existing anti-HIV drugs, Trimeris's fusion inhibitors did not aim at stopping HIV from replicating after it invaded a cell. Instead, the new compounds promised to stop the virus from entering the cell in the first place. Trimeris had the basic science, had successfully gone public, and had funded and completed the basic development and initial phases of testing. At this stage, many technology companies start thinking about a future of licensing deals.

The Trimeris-Roche discussions begged for more than just another typical licensing agreement. Beyond the need to complete clinical trials and market the drugs, Trimeris's compounds presented a host of more exceptional challenges. Traditional chemistry produces small molecule drugs that are relatively easy to produce once formulated. Trimeris's discoveries were not typical, chemical-based, small-molecule pharmaceuticals. They were long and complex peptides, chains of amino acids similar to (but not quite) proteins. For patients, in practical terms, this also meant that the drugs would need to be injected. Trimeris's compounds would be much more difficult and costly to produce and deliver than the usual pill. Trimeris needed a substantial partner who could help further fund and develop relatively novel, complicated, and expensive manufacturing and delivery processes. As Roche noted, Fuzeon (as the lead compound would be named) was "one of the most complex and challenging molecules ever chemically manufactured on a large scale by the pharmaceutical industry."

Trimeris and Roche initially agreed to share equally both the development expenses and profits in the U.S. and Canada. Roche would commercialize and market the drugs elsewhere, paying royalties to Trimeris. The anti-HIV compounds soon received "fast track" status from the U.S. FDA. By 2000, Fuzeon entered Phase III clinical trials and Trimeris' continued to transfer its complex peptide-manufacturing knowledge to Roche's production facilities in Colorado.

In 2001, the partnership was expanded as the venture progressed. Under the terms of a new three-year agreement, renewable thereafter on an annual basis, Trimeris and Roche would equally fund worldwide research, development, and commercialization, as well as equally share the profits from worldwide sales, of any new HIV fusion inhibitor peptides. By 2003, Fuzeon received approval from the FDA and, especially because of the unfortunate rise of drug-resistant HIV, Roche literally could not produce enough of it to meet demand.

Avoiding Joint Problems

Trimeris and Roche's successful partnership is an example of how innovation alliances can be essential, fruitful, and profitable—even, in some cases, to tackle the tasks of core innovation. But if it's really a core issue, such collaboration must be closely monitored by and tightly integrated with its parents. Elan Pharmaceuticals's near collapse in 2002 provides a useful and interesting contrast. The Ireland-based drug company had numerous promising new compounds under development for a wide variety of conditions. However, Elan chose to push the development of each drug as part of a complex web of several dozen independently incorporated joint ventures. In return, Elan got to dump expensive drug development costs onto these joint ventures, even while registering revenues by selling technology licenses to them. This R&D joint venture structure made Elan's own corporate performance appear much richer and healthier.

In late 2001, however, heightened scrutiny over Elan's innumerable joint ventures raised many concerns. Fancy financial accounting gimmicks suddenly were out of style. Few could make sense of the company's workings or its true worth. Elan's market value quickly plunged from $20 billion to less than $1 billion, accompanied by a series of lawsuits, investigations, and management turmoil. Elan subsequently divested many, and reconsolidated the rest, of its previously "independently" joint-ventured drugs. It did not eliminate all its drug development partnerships by any means; instead, it just brought the ones it retained back into account and back under control.

After a couple years of quiet retrenching, Elan bounced back. In early 2004, just one of its targeted development alliances with Biogen had notable success when its multiple sclerosis drug Antegren was approved by the U.S. FDA. Elan's market capitalization quickly increased ten-fold.

Elan's saga illustrates a recurring theme and one of our own main points. The how of innovation matters as much as the what. Elan had numerous compounds under development, each with fantastic promise. There was no shortage of real science or real promise. Its too-novel, off-the-books joint venture approach to developing these drugs, however, brought it great troubles. As with all the other innovation options we discuss, alliances must be formed for the right reasons, and in the right way, to maximize their chances of success. If they're crucial to a firm's core innovation needs and challenges, they probably need to be tightly managed as such—not as loosely structured and lightly managed organizations of their own accord.