Chapter 6. Spinnovation: Liberating Value or Spinning Out of Control?

"By combining the entrepreneurial atmosphere of a startup venture with the financial and managerial strengths of a large, well-established company, I believe we have created a new kind of corporate enterprise."

—George Hatsopoulos

Most of the other newfangled approaches to innovation (e.g., corporate venturing and R&D by M&A) focused on aggressively attempting to bring more innovation inside the firm. The explicit idea of the spinout was far different. The objective and method of the spinout was to cast bigger and better innovations outside the parent organization. Spin out even the best and most promising core innovations to set them free and let them flourish.[1] Spinouts proliferated as offspring of everything from retail consumer firms to old-line industrial equipment makers. Corporate dot-com spinouts became the most common expression of the idea, but they were hardly the only type or form.

A spinout required the creation of a separate firm, a new company legally and organizationally distinct from its parent. The spinout would have its own formal and independent incorporation, board of directors, management team, financial statements, and equity. A spinout's key distinguishing feature was that it was clearly a distinct corporate entity, not just another corporate division or subsidiary of the parent.

The idea of spinnovation was still largely a curiosity even by the mid 1990s. The concept really took off as the technology boom and frenzied financial markets encouraged the birth of numerous high-tech corporate offspring during the latter half of the decade. The basic thinking was that successful development and commercialization of corporate innovation required new and different types of organizations and new and different types of organizational structures, ones that went even far beyond simple corporate venturing. With corporate venturing, the buck (literally and figuratively) still stopped with the corporate parent. However creatively structured, internal corporate ventures ultimately reported to the top of the company's chain of command and depended on the budgets and blessings of corporate headquarters.

Liberating Innovation?

Spinouts offered a better, more liberated solution. A successful innovation organization didn't have to just act more like a startup (an internal corporate venture), but it had to actually be more like a startup. It had to be spun out. By creating legally and organizationally separate new ventures, spinouts could liberate powerful new ideas and high-promise ventures that ached to break free from the stifling atmosphere of the parent company's established corporate bureaucracy. Ideally, spinouts had the best advantages of respected corporate parenting, while also having the increased freedom, focus, and motivation of a startup entrepreneurial venture.

Perhaps just as importantly, spinouts' unique organizational, legal, and financial structuring offered the opportunity for parents to raise large sums of outside capital to fund promising, but risky, ideas. Venture capital or other forms of private investment, or even the public markets directly (through an IPO), could be tapped to share the costs and risks. Moreover, compared with a typical entrepreneurial venture, raising cash would be easy. Investors would buy in quickly and contribute more with a respected corporate parent as a namesake founder, primary co-investor, and privileged nurturer of its own spinout offspring. Good parenting and pedigree conferred substantial privileges.

Spinouts offered other organizational and financial advantages. With separate, dedicated equity for the spinout, the parent and its partners could craft high-powered incentives (e.g., stock and options) for spinout managers to be more truly aggressive entrepreneurs. The stock of an old-line S&P 500 company simply couldn't compete with the potential upside of a real stake in an entrepreneurial spinout. In contrast, internal corporate venturing offered the possibility to create "phantom" stock and options at best. With a spinout, the opportunities for big-payoff financial incentives were very real and almost unlimited. These were not phantom shares; they were cold, hard, real equity. They offered a more clear, direct, and powerful fuel for entrepreneurial energies. They also offered potential currency with which to do deals or otherwise entice and enlist partners, customers, and other stakeholders.

After setting the spinout structure and process in place, corporate parents could ease back and watch their offsprings' value soar as the latent potential of previously languishing corporate innovations was unleashed. Newly focused entrepreneurial spinouts would flourish. At the same time, by keeping significant strategic and organizational ties, as well as significant ownership stakes and other financial links to their newly spunout ventures, parent companies would still be able to realize synergies with their offspring and, ultimately, would be able to capture most of the ultimate value created.

Corporate.coms

With the advent of the Internet, spinouts seemed particularly attractive and appropriate. Established companies could spin out Internet versions of themselves to beat startups at their own game. The list of dot-com spinout ventures quickly expanded: Barnes&Noble.com, Bluelight.com (Kmart), FTD.com, McAfee.com, Playboy.com, RadioShack.com, Sales.com, Staples.com, ToysRUs.com, Walmart.com, and so on. The thinking was that the core established firms simply couldn't or shouldn't try to embrace the Internet wholly themselves. The technologies, cultures, and business models were just too different and disruptive. The parent firms simply "didn't get it"; even if they did, they were too stodgy and slow to react. Moreover, the parent companies did not always have, or want to invest, the significant capital required to take their e-commerce dreams to fruition—at least not as quickly and grandly as they needed to. Spin out a corporate dot-com, however, and analysts and investors, talent and customers, all would swoon.

Just as quickly as they had proliferated, most Internet-era spinouts quickly fizzled. They often left a trail of less-than-stellar investments and strategic, organizational, and legal complications in their wake. Typical of the other innovation fads and fashions, the promotion of spinouts as a new and uniquely powerful model for innovation continued to gain momentum even as many high-profile spinouts—including many companies featured as exemplars—already were experiencing serious difficulties. Within just a couple years, most of these innovation-driven spinouts were spun back in, sold off, or shut down.

Enduring lessons can be learned from these numerous stumbled spinouts. As with the other innovation fads and fashions, it's too easy to dismiss their rise and fall as just an inevitable function of the overall craziness of the Internet boom and bust. This is not the case. Spinouts were not only the rage for old-line companies looking to tap the power and possibilities of the Internet. Many other companies in a wide variety of industries—from industrial goods and retail to biotech and pharmaceuticals—also pursued spinnovation as a solution for their innovation challenges. From Thermo Electron to Toys R Us, the examples show that, despite their myriad theoretical and potential advantages, the promise of spinouts often falls short in practice. This does not have to be the case. Spinouts have the potential to liberate and create enormous value—if done right, and for the right reasons.

Spinning Out of Control

The recent history of Thermo Electron illustrates the dynamics and challenges of the spinnovation strategy. George Hatsopoulos, the founder of Thermo Electron, was one of the great entrepreneurs and company builders of the past few decades. Starting in 1956 with $50,000, he built Thermo Electron into one of the world's leading technical and medical equipment companies during the next 40 years. For most of its history, Thermo Electron methodically went about building its businesses, adding new technologies and divisions to its incrementally expanding corporate portfolio. It was a successful but quiet company involved in a wide variety of markets such as test, measurement, and monitoring equipment. But it was not a Wall Street darling, to say the least.

During the mid 1980s and early 1990s, Hatsopoulos embarked upon a novel strategy, one that would eventually garner more attention and much greater financial acclaim. Hatsopoulos was frustrated by the need for more capital to build Thermo Electron's technology-intensive businesses. He was also intent on fostering among his managers the same sort of entrepreneurial spirit that drove him to found Thermo Electron. To address both concerns, Thermo Electron began to spin out more and more new technologies as independent but still Thermo-affiliated companies. The flurry of offspring eventually generated more than a couple dozen spinouts, many with their own IPOs and publicly traded shares. Several of the spinouts then went on to spawn their own new technology spinouts. Thermo Electron typically maintained a majority ownership stake in its offspring and also maintained numerous other administrative, financial, and organizational ties.

The logic was simple but compelling: Leverage the incubational and operational benefits of scale and support that a large corporate parent (Thermo Electron) could provide, while simultaneously gaining the financial and entrepreneurial flexibility of focused, IPOed, new business ventures. Everyone would benefit: Thermo as the corporate parent, the spunout businesses and their managers, and outside investors and partners:

-

The Parent—Thermo Electron would be able to independently raise capital for each of its spunout businesses. Through private fundraising and especially public equity issues (IPOs), it would be able to fund promising, but risky and capital-intensive, new technology ventures better and cheaper than it could through internal corporate funding. Thermo Electron still would reap most of the gains of any successes by maintaining a large (usually majority) stake in each of the spinouts, as well as by securing other revenue streams from its offspring through ongoing technology, marketing, and administrative affiliations.

-

The Spinout—Managers and technical talent of the new spinout ventures would gain the liberation of entrepreneurial ownership and control that would never be possible as just another internal corporate division. Managers could make their own strategic decisions and then share in their own successes through their direct, real equity and option stakes in the spinout. Thermo Electron could thereby better attract, retain, and motivate top technical and managerial talent. At the same time, all the spinouts would continue to benefit from having the ongoing, supportive parentage and pedigree of Thermo Electron to help incubate and support their nascent technologies and businesses.

-

Investors and partners—Investors and other potential partners could join Thermo Electron in supporting clear and focused entrepreneurial spinout ventures whose strategic and financial potential wouldn't get buried within the complexity and bureaucracy of the corporate parent. Unlike with a typical high-risk startup, investors would get the benefit of buying into more mature and developed spunout technologies that had been, and would continue to be, looked after by a respected corporate parent. Raising additional capital and dealing with the financial markets would be easier for each individual technology venture. Separate spunout businesses would provide much greater simplicity and clarity for analysts and investors alike.

In the wake of this radical and ever-expanding strategic, organizational, and financial experiment, revenues of the Thermo group grew dramatically. The market richly rewarded both the parent and its spinouts. Thermo Electron's market value tripled from 1993 to 1996. The enthusiasm for Thermo Electron's strategy was so great that a dedicated mutual fund sprouted in 1996 to try to tap into its success. The Thermo Opportunity Fund was founded to invest the majority of its assets in Thermo Electron and its various offspring. Thermo became not only a Wall Street darling, but also the focus of numerous glowing case studies and articles in both management and finance.

Thermo Electron's spinout structure seemed to offer many substantial benefits that alleviated or solved some of the key problems of corporate innovation. It was ideal in the sense that, carved out from the parent, the spinout strategies "...subject units of the company to the scrutiny of the capital markets, allow the compensation contracts of unit managers to be based on market performance, and shift capital acquisition and investment decisions from centralized control to unit managers."[2] Each spinout was more nimble and focused, offering great benefits to both investors and managers. At the same time, the continuing interrelationships and leverage of the overall Thermo portfolio offered ongoing benefits of synergy and diversity to each spinout, all unified by a strong common corporate parentage. It was the best of both worlds.

Another exploration of Thermo Electron's novel spinout business design offered similar observations: "From a technology company that developed and manufactured products, Thermo Electron transformed itself into a [sort of] venture capital firm that spins out promising technologies into separate units and supports those units with financial backing, technical know-how, and other business resources."[3] Thermo was now something different, something much more than just a technical and medical equipment manufacturer. Thermo Electron offered a new model for innovation: the corporate innovator as the hub of a network of aggressive, entrepreneurial spinouts. Thermo wasn't just spinning out peripheral new technologies; it was spinning out some of its best and biggest innovations.

Unraveling of the Spinouts

Even as the accolades grew and as its spinnovation began to be increasingly emulated, Thermo Electron and its investors began to have some serious doubts and second thoughts about the strategy. By 1998, they no longer saw the focus and drive of individual entrepreneurial ventures or the clear and powerful discipline of the financial markets. They woke one morning to instead see a corporate holding company at the center of a confusing constellation of two dozen partially spunout subsidiaries. Each quasi-independent spinout had its own board, meaning the entire Thermo constellation of spinouts generated more than 100 board meetings per year. Managers complained that Thermo was a series of fiefdoms and that it was often more difficult to do business with a fellow Thermo spinout than it was with a competitor. Each spinout had duplication and overlap in many basic business operations and functions. Customers and investors were confused: Who and what was Thermo Electron? The incoming president admitted that he didn't know what exactly Thermo Electron was until he was offered the job, even though he had been doing business with numerous Thermo spinouts for years.

On the financial side, many of the spinouts languished as they failed to attract and maintain sufficient levels of interest from analysts and investors to keep their stocks afloat. They simply were too small in terms of revenues and market capitalization (ranging as low as in the tens of millions) and too thinly traded to attract enough attention. Worse, analysts and investors found it increasingly difficult to make sense of Thermo Electron's complex web of strategic, organizational, and financial ties to its numerous spunout offspring. When Thermo Electron reported negative results in one of its major spinouts in early 1998, the questions and doubts grew and the parent's own stock began a deep and hard slide.

Many of the supposed benefits of Thermo's spinout strategy appeared to quickly unravel. To management and employees, analysts and investors, Thermo's constellation of spinouts had become more confusing than clear, and more cumbersome than liberating. In one year, Thermo Electron plummeted from almost $40 per share to nearly $10, even as the economy and the market continued to glow and grow. Clearly, the gloss was off Thermo's previously much celebrated example. Thermo Electron's founders retired. A new management team came on board.

Refocusing the Core

Thermo Electron's new leadership started their job by conceding that many of the company's spinouts were, in fact, core businesses that needed to be brought back more fully and formally under the corporate umbrella. Conversely, other non-core businesses needed to be fully and unequivocally divested, not just partially spun out. In January 2000, three months prior to the tech market crash, Thermo Electron announced a sweeping reorganization. The company initiated plans to buy back most of its spinout subsidiaries. Other non-core, partially spunout assets were to be wholly and completely divested.

Thermo Electron began transforming itself into a single, unified company focused on life sciences, optical technologies, and test and measurement equipment. The goal of the new strategy was to become one unified, publicly traded firm with a greatly simplified structure—to become "a highly integrated, tightly managed operating company." Thermo Electron billed its refocusing as making it "the first post-'90s company." Starkly contrary to the logic of the prior spinout-driven strategy, Chairman Richard Syron explained, "We knew that making Thermo one company focused on one industry would unlock the value within Thermo, make us competitive for the future, and position us for growth." By the end of 2001, Thermo had undone almost all of its spinouts, dramatically reversing its earlier, radical, spinnovation experiment.

Spin.com: How Not to Spin

Thermo Electron's spinout strategy set the model for the flurry of technology and Internet spinouts that soon followed. Yet, even as Thermo Electron's constellation of spinouts collapsed in 1998 and 1999, few outside the company seemed to notice or carefully consider Thermo's now more complicated spinout experiences. Few lessons were learned. The spinout strategy took on new glamour and urgency, as everyone from established blue-chip companies, such as Wal-Mart, Staples, Enron, and Tyco, to dot-com retailers and Internet media plays, jumped onto the spinout bandwagon. Just a few weeks after Thermo Electron announced its massive unspinning, for example, Wal-Mart announced it was partnering with VC co-investors Accel Partners to spin out a new Silicon Valley–based offspring, Walmart.com.

The vast majority of these Internet and technology spinouts just being launched would struggle with exactly the same sorts of dilemmas that had plagued Thermo Electron. Spinout stumbles followed in a wide variety of companies and industries:

-

Wal-Mart/Walmart.com—Wal-Mart retained a majority stake, but eventually spun it back in, buying back VC-owned shares to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

-

Kmart/Bluelight.com—Kmart retained 60 percent, but then spun it all back in by buying back VC-owned shares to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

-

Staples/Staples.com—Staples retained 82.5 percent, but then reversed a planned spinout IPO; it bought back VC and employee shares to make the dot-com a wholly owned subsidiary.

-

FTD/FTD.com—FTD retained 98 percent of voting stock, but then spun the dot-com back in entirely by buying back its public shares, saying FTD.com was "too small a company to move forward" on its own.

-

Network Associates/McAfee.com—Network Associates retained 85 percent, with 95 percent voting shares, then down to 75 percent, but spun the entire thing in, buying back all publicly held shares to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

-

Nordstrom/Nordstrom.com—Nordstrom retained a majority stake, but then spun it all back in by buying back outside investors' shares to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

-

Playboy/Playboy.com—Playboy planned an IPO for its dot-com offspring, but canceled it at the last minute; Playboy.com instead became a new corporate division.

-

Siebel Systems/Sales.com—Siebel retained a big minority stake, but the entire venture was shut down in July 2001; Siebel Systems launched its own internal Internet division in 2003.

-

RadioShack/RadioShack.com—RadioShack retained 75 percent, but then spun it all back in by buying back the 25 percent outside interest.

-

Toys R Us/ToysRUs.com—Toys R Us retained a majority stake, but a deal with VC partners was subsequently withdrawn and the dot-com venture instead became a wholly owned subsidiary.

It wasn't just corporate dot-coms, either. Other examples ranged from pharmaceuticals to utilities to fiber optics:

-

ICN/Ribapharm—ICN initially retained 80 percent, but then spun it all back in by buying back all publicly held shares to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

-

Enron/Azurix—Enron retained 67 percent, but then spun it back in entirely by buying back all publicly held shares.

-

Tyco/Tycom—Tyco retained 86 percent, but then spun it back in entirely by buying back all publicly held shares to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

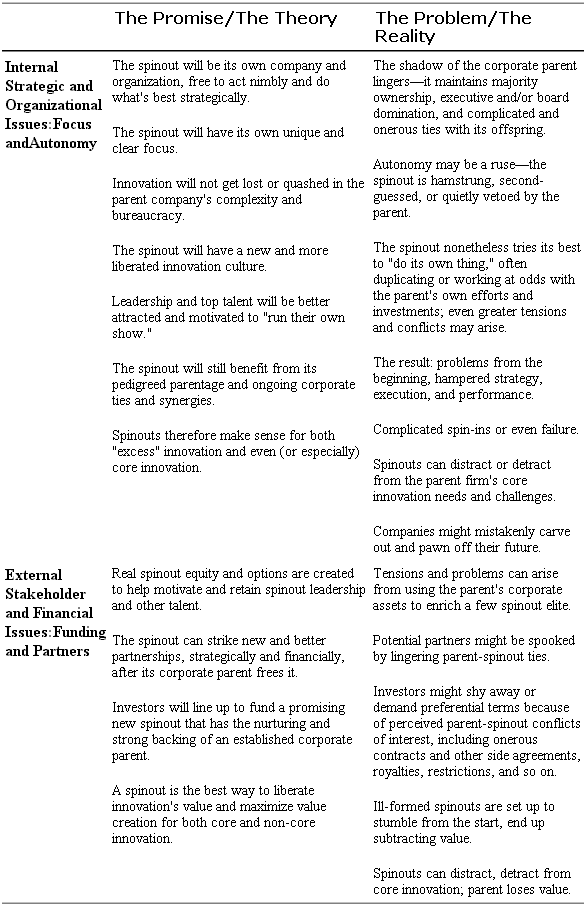

In examining the history of dozens of other cases of spinnovation, the overall record was mixed and often disappointing. Many were plagued by difficulties from the start (see Table 6-1). The initial difficulties and failed or spun-in spinouts all tended to share one or more (often all) of the following common problems:

-

The crown jewels spinout—Innovation assets too close to the parent's core were spun out, often followed by regret, reconsideration, and eventually attempted "recall" of the spinout. But undoing a spinout might not be a simple transaction at all—including legally, organizationally, and financially. A spinout might seem the best way to provide the clarity and focus needed for a large and established firm to grow some of its most promising new ventures, even its core innovations. A spinout might appear to offer a more entrepreneurial structure and culture, as well as new capital and fresh equity, not available when innovation remains buried within a corporate bureaucracy. Before long, however, many parents fret that they might have spun out some of their crown jewels. After this realization hits, it's not always easy or cheap to buy them back. From Old Economy R&D spinouts to the myriad corporate Internet dot-com offspring, this is a common spinnovation dilemma.

-

The one-legged stool spinout—The spinout could not stand on its own terms and could not gain traction as an independent operating business. Companies might try to spin out embryonic, partially formed ideas and inventions that have limited coherence and shaky standalone business models. A premature idea or a mere piece of a business model (such as some raw, basic science or a single sales channel) is usually not a good foundation for a successful, standalone spinout. Most of the corporate Internet dot-coms fell victim to this problem: Bluelight.com, FTD.com, McAfee.com, Nordstrom.com, Playboy.com, RadioShack.com, Staples.com, ToysRUs.com, Walmart.com, and others. A successful spinout should have a credible independent business case in terms of strategy, operations, and finances. If it doesn't, the parent needs to decide whether to simply re-integrate the innovation into its own core businesses or to invest what might be considerable time and resources to nurture it further so that it might be later spun out. Alternately, the parent might try to partner, license, or sell the innovation to let someone else incubate it further, or just simply shelf the idea altogether.

-

The piggy-bank spinout—Another common problem was the piggy-bank spinout. The spinout was primarily motivated by short-term financial exigencies or accounting gimmickry, such as the desire to goose financial statements by getting rid of expenses and debt or to raise quick cash, instead of building a sound long-term strategy. In many new business ventures, capital requirements are large, the risk is substantial, and the payoffs can be relatively distant. The parent firm might be hesitant to commit large resources to a new venture, even if it looks like a core investment. The corporate parent might be more concerned about quarterly earnings reports or other short-term financial exigencies. Raising capital externally through a spinout therefore proves to be alluring. But myopic financial gimmickry can create more problems than it solves if it's used only to avoid (or, more likely, simply delay) the pain and responsibility of tough investment choices. Over time, purely financial-driven spinout decisions aggravate numerous tensions, including conflicts of interest for the parent, spinout, and investors alike. Many of Enron's infamous spinouts, from new utility companies to new Internet ventures, and others, such as Tyco's Tycom spinout, fell into this category. In smaller or much less scandalous ways, so did many other technology and non-technology spinouts alike (for example, ICN-Ribapharm and many corporate dot-coms).

Table 6-1. Liberating Value or Spinning Out of Control?

All the above problems tend to interact and compound each other. The vast array of retail spinouts, such as Walmart.com, Bluelight.com, and Staples.com, were born of Internet euphoria, when it seemed that the web would transform retailing and leave brick-and-mortar retailers in the dust. Promoters extolled the benefits of spinouts as a way both to externally raise quick cash and to respond in a fast and entrepreneurial way. Soon enough, however, ill-formed Internet-retailing business models struggled on small volumes to support their own marketing, operations, finance, human resources, distribution, and fulfillment efforts. Both Walmart.com and Bluelight.com were bought back and spun in by their corporate parents less than 18 months after being spun out.

Staples.com was one of the more initially successful online-retail efforts. However, parent Staples's plans to spin out Staples.com and do an IPO were cut short as the spinout's foggy strategic and financial rationale quickly evaporated. Instead, Staples.com was pulled back and folded into Staples's core business. Reversing their earlier thinking, Staples's executives now noted that Staples.com indeed was an integral part of, and key channel for, the parent firm's core business. Even simply stopping the Staples.com spinout-in-process created problems. Some Staples shareholders revolted and filed suit as the parent tried to buy back Staples.com executives' pre-IPO equity of the now-defunct spinout at what were viewed as unfairly inflated prices.

The Umbilical-Cord Spinout

What Thermo Electron, the myriad dot-com corporate spinouts, and so many other spinouts also have in common is an "umbilical cord" dilemma. The parent company cannot bring itself to sever its continuing ties of ownership and control with its own offspring. The parent might be reluctant to let go because the business really shouldn't have been spun out in the first place. Or, the parent simply might not want to share too much of the spinout "pie" with outside partners and investors. To try to better profit from the spinout, for example, parents often press onerous conditions on their offspring: high royalty payments, restrictive and expensive licenses, exorbitant management fees, guaranteed buyer/supplier contracts, and so on. As a result, the too-close, continuing corporate relationship smothers or strangles the fledgling spinout. Ultimately, the ties that bind can cause strategic, organizational, legal, and financial difficulties for the parent as well.

Whatever the reasoning and objectives, a partial "umbilical cord" spinout is often little more than another subsidiary of the parent; many relevant stakeholders perceive it as exactly that. Any sort of quasi-autonomy given to a spinout under these conditions is, at best, a weak substitute for true independence and, at worst, is simply a ruse. Continuing entanglements with the parent firm are likely to interfere with effective decision making for the spinout, which to succeed needs to truly chart its own course. At the same time, the lingering shadow of the parent can spook key outside stakeholders, particularly potential partners and investors. The variety of tensions and conflicts that result can cause considerable complications for both spinout and parent.

The spinout of Barnes&Noble.com reveals some of these inherent complexities. After Barnes & Noble took public one-fourth of the dot-com spinout in 1999, shares briefly bumped up, but then slid down from an offering price of $18 to less than $1 over the next couple years. Barnes & Noble eventually decided to buy back the dot-com shares and make the spinout a full subsidiary. The reasons? To cut combined costs (not just operating costs, but also the costs of administering two separate public companies) and to strengthen the Barnes & Noble brand. Barnes & Noble initially offered $2.50 per share. The offer was quickly followed by more than a dozen lawsuits charging that the deal was "inadequate and constitutes unfair dealing." The suits alleged that Barnes & Noble had unfairly abused its dominant stake and "breached its duty" to Barnes&Noble.com shareholders. Barnes & Noble upped its offer and settled the suits, completing the spin-in in early 2004. These types of entanglements are only some of the more visible symptoms of the more fundamental burdens—strategic, organizational, legal, and financial—under which many spinouts labor.

Navigating a Spinout

Despite the numerous possible pitfalls, spinouts—done right and for the right reasons—still offer the potential of maximizing value creation from innovation. This includes not only for the parent and spinout, but also for outside partners, investors, and other stakeholders. Innovations that might have died on the vine or simply languished inside the corporate parent can instead be brought more quickly and fully to fruition. This is especially the case for non-core, but still potentially valuable, innovations. From initial consideration and throughout implementation, however, spinouts present a series of critical decision points and execution hurdles. Spinouts necessitate a strategy process in which parents initially must invest and take charge. But sooner rather than later, the parents need to step back, let go, and refocus on their own core businesses, even as the spinout is set free to chart its own course.

The story of Targacept, Inc. provides a good illustration of how, when, and why spinouts can fit into the innovation mix. Targacept, a development-stage pharmaceutical firm, was spun out from R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Targacept's journey illustrates not only the uses and challenges of the spinout strategy, it also highlights some of the key issues raised by all the other innovation approaches discussed thus far—i.e., the inherent problems of corporate venturing, the limitations of IP licensing, the difficulties of partnering, and the dilemmas of innovation by acquisition.

Corporate Venturing and Innovation Spillovers

Innovation is not a defined and predictable endeavor; a tremendous amount of creativity, serendipity, and unintended discovery is inherently involved. Consequently, in the process of substantially and continually investing in R&D and new business development, firms are likely to have significant innovation spillovers. They might find a lot of what they weren't necessarily looking for in the first place. Other times, a firm's initial innovation goals can be both clear and achieved, but time and circumstances might have diminished their relevance and attractiveness for the parent firm's now-evolved strategy. A company might face the dilemma of having a plethora of potentially valuable innovation assets that no one knows what to do with. This problem of excess innovation is especially prevalent inside larger companies, with sometimes dozens of different R&D programs and enormous annual research and new business development expenditures. Xerox and Lucent are two key examples of this (see Chapter 2).

The problem of excess innovation also happens in some of the most unlikely places. In the early 1980s, the leadership of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco (RJR) made a strategic decision to invest in a strong focus on science. The idea was that RJR should be the world's leader in understanding nicotine and related issues—the pharmacology, the chemistry, and the toxicology. Top management believed it would help develop safer products and help better address controversial issues, such as addiction. Much like many other R&D skunkworks and corporate-venturing initiatives, the Nicotine Research and Analogue Development Program (NRADP) was well funded and set loose.

For nearly 15 years, RJR devoted millions of dollars to fund NRADP. A rich talent pool and world-class research programs grew. The operation was run much like a research institute, with an environment as much academic as business. A lot of far-reaching basic R&D, in which a company might not normally invest, took root. The labs were incubating new ideas, patents, and technologies, and ever-more derivatives of each. Eventually, some researchers began to realize that the discoveries for which they had labored so long and so hard might actually have some commercial applications. One serendipitous discovery was that many of the compounds that NRADP scientists were working with seemed to have potential applications to alleviate a wide variety of ailments: Alzheimer's disease, pain, depression, schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, ulcerative colitis, attention deficit disorder, Tourette's syndrome, obesity, and other problems especially related to the brain and central nervous system.

At the same time, scientists outside RJR were noting that tobacco users had reduced susceptibility to, and symptoms of, many such ailments. Nicotine appeared to be one common reason why. Although nicotine is quite toxic and has many negative side effects, in small dosages it might also have notable beneficial effects. Some of RJR's researchers began to explore how and why beneficial effects existed. They also focused more on exploring how the negative side effects of nicotine could be greatly diminished or even eliminated by creating entirely new but similar-acting compounds. Nicotinic-based compounds had the ability to "tune" the brain and central nervous system.

Cigarettes and Pharmaceuticals Don't Mix

Despite the NRADP's scientific progress, RJR's R&D skunkworks began to encounter difficulties. By the mid 1990s, top executives of RJR and its parent, RJR Nabisco Holdings, could no longer afford to spend their limited time, attention, and resources on some of the company's more promising, if surprising, new ventures. RJR Nabisco Holdings was in the middle of its own conglomerate breakup. Moreover, as heavy political and legal pressure on the tobacco industry mounted, RJR itself had to retrench and refocus on running its core operating businesses. Years and millions of R&D investment and some fantastically promising discoveries now just seemed to be off purpose. NRADP had some potential blockbuster innovations that nonetheless were largely irrelevant to the other huge and more immediate strategic problems RJR confronted. Corporate interest in and funding for NRADP suddenly evaporated.

Originally, NRADP's proponents had wanted to leverage its discoveries to transform the whole of RJR itself into a different kind of company. This ambitious agenda withered in the face of organizational, industry, financial, political, and legal realities. Although only a few years earlier it had been the focus of corporate R&D, NRADP was now out of fashion and out of favor in a company with many more pressing priorities. Continuing to fund and develop NRADP within RJR appeared to be a quixotic battle.

It's a common and vexing corporate-venturing problem; NRADP just didn't fit the more immediate core challenges of the parent firm. RJR's main business revolved around a simply manufactured agricultural product rolled in paper. An R&D-intensive pharmaceutical business was hardly a strategic fit with a huge cigarette business. Continuing to invest in NRADP no longer made sense.

NRADP faced extinction. Although many executives saw the latent value of its R&D, they simply could not justify supporting it any further. Some executives wanted the research program abruptly cut off and shut down altogether. Others were content to quietly extinguish it. RJR CEO Andy Schindler noted, "The scientists were enthused about the potential. But, there was no clear path to fruition for RJR."

Considering the Alternatives

Still others thought that RJR should at least try to sell or license NRADP's intellectual property portfolio to earn some nominal payback. The limited value of the raw intellectual property proved a problem. NRADP's compounds were still a long way from being tested, developed, and proven as safe and effective therapeutic drugs. Sale or license of the intellectual property would bring in only thousands of dollars, not millions. As one executive later noted, "[T]he intellectual property was not worth much, had no real, significant monetary value. We would've gotten almost nothing if we had just tried to license or sell the raw science." It was hardly worth the effort and expense.

Innovation by acquisition also proved an infeasible option. In RJR's strategic and financial predicament, it was not at all practical to try to acquire more pharmaceutical R&D and drug development assets to try to push NRADP's discoveries further toward commercialization. The idea was surfaced, but quickly scuttled. It would be hugely expensive, take far too long to bear fruit (6–8 years minimum), and pull RJR only farther from its core, cash-generating businesses into unknown territory. RJR CEO Schindler explained, "If we had followed a go-it-alone path and had tried to develop this internally [within RJR], I think we would've failed. We had no sense of the end game as a tobacco company." Neither would investors have the patience or understanding for such a move. RJR had neither the luxuries of cash and time nor the competence and capabilities to try to transform itself into a pharmaceutical company.

Partnering seemed the next logical option to consider. But pursuing an alliance or joint venture raised its own dilemmas. As NRADP's scientists communicated their discoveries with their Big Pharma colleagues, great initial interest and enthusiasm grew. NRADP's targets and compounds offered novel approaches to try to tackle an entire series of prevalent, debilitating central nervous system conditions. After executives at one interested Big Pharma firm realized that they were talking to, and potentially collaborating with, a tobacco company, however, the discussions abruptly cooled. RJR carried considerable baggage. A joint venture or another form of ongoing collaboration did not seem a viable long-term option.

Launching a Spinout

Before making a final decision on simply shutting down NRADP, RJR brought in an outside advisor to help it surface and assess any other alternatives. A different approach was proposed, a more involved process designed to eventually spin out NRADP as an independent firm. NRADP met the strategic criteria as a good candidate for a spinout. It was no longer part of a core R&D or new business development initiative for RJR. Still, RJR's years of investment had given it solid and diverse assets to try to flourish as an independent venture. The spinout wouldn't be a "one-legged stool." It wasn't a single patent or idea, but an entire functioning group of productive resources: myriad patents, researchers, technologies, and capabilities. Moreover, a spinout offered much greater upside than any of the other options, at least if it succeeded. A bit more investment and patience would be required. Pursuing a spinout was definitely not the easiest and quickest option, but it appeared to be the best (if not the only) way to eventually realize any of NRADP's latent value.

RJR's situation highlights the balancing act of pursuing a spinout strategy. A prospective spinout-in-process must somehow survive and be nurtured as part of the parent even as it needs to plan and begin to implement its own course toward independence. The parent firm cannot afford to waste undue time, attention, and resources on executing the spinout. After all, the parent's decision to spin it out inherently suggests that it's no longer a core strategic concern.

For RJR, it was a tough trick. RJR's total R&D budget had been cut by more than half; NRADP's funding dried up. Yet, it needed millions to continue R&D. RJR CEO Schindler told NRADP's leaders it would be shut down by the end of 1998. After some heated discussions, a deal was struck: NRADP would get no more money after the year's end, but it would not be shut down. NRADP would get a chance to make a go of it, if it could figure out how to bootstrap its own support.

The spinout idea offered one possible solution. If NRADP could find outside partners and investors to facilitate the process, it might actually have a chance. RJR CEO Schindler explained his skeptical, tough-love approach, "By threatening to shut it down, I was trying to spur it to the next step. They needed that pressure; this is the kind of pressure that a new venture needs to succeed anyway."

The Process of Breaking Free

The NRADP team had to push to define the spinout's focus and purpose. It could not survive on its own as a loose gaggle of quasi-academic researchers. It had to define a vision, mission, scope, goals, and objectives as a would-be independent company. The decision was made to leverage NRADP's core patents and capabilities focusing on the brain and central nervous system. The group also brainstormed a corporate identity and name: Targacept, stemming from its R&D focus on targeting key nerve receptors. Without a well-defined strategy and purpose of its own, a fledgling spinout cannot build a credible standalone business case.

A lack of defined strategic scope and direction for a spinout can also create major conflicts between the spinout and its parent down the road. These "turf" battles can endanger a spinout's chances of success and, as the previous examples highlighted, create complex legal, strategic, and financial headaches for the parent. If the parent has serious hesitations about surrendering too much territory and freedom to its proposed spinout, it might be reason to re-examine whether a spinout is a good idea in the first place. Onerous restrictions and conditions on the spinout ultimately tend to be deleterious to both the parent and offspring.

Fortunately for Targacept, the territorial boundaries between RJR and its proposed spinout were fairly clear cut. It was unlikely that RJR would anytime soon develop a renewed interest in pharmaceutical R&D. Therefore, the more detailed process of legally, organizationally, and financially extricating Targacept from RJR got underway. RJR established Targacept as an independent subsidiary company with its own employees, assets, and financial statements. Fortunately for Targacept, RJR avoided the all-too-frequent "umbilical cord" dilemma and instead outright assigned all the core intellectual property wholly and clearly to Targacept.

Partners and Investors as Validation

Parents need to step back for their own good and for the good of the spinout. Outside partners and investors need to begin to play more of a major role, helping a spinout advance farther along in the process of gaining functional independence. Active outside partners and investors also provide critical validation for the entire concept of a spinout. If a spinout cannot attract substantial, credible, and committed outside partners and investors, it's usually a sign that the choice of a spinout strategy is flawed. It might not be a valid or sufficiently incubated concept. As RJR CEO Schindler noted, "We needed outside investment from serious partners as validation for what we had. They [pharmaceutical firms and VC investors] know the business much better than I did."

In early 1998, the new (but still 100 percent RJR-owned) Targacept subsidiary made overtures to a U.S.–based pharmaceutical giant, seeking research funding and collaboration to keep from being shut down. Negotiations proceeded smoothly and the possibility of a rewarding partnership looked promising. However, when senior executives of the promising pharmaceutical partner became aware of RJR's role, negotiations abruptly ended. Again, they hesitated to partner with a tobacco company.

As in so many spinout situations, Targacept's lingering corporate parentage, though initially providing the substantial benefits that only a generous corporate parent can provide, had now become a liability. Targacept learned its lesson. By the end of 1998, Targacept committed to a full spinout and struck a funding deal with drug giant Rhone-Poulenc Rorer to jointly explore therapies for Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases.

Targacept's dealings with outside investors also highlighted the need to be free. One interested VC stressed, "I am going to cut to the bottom of this: We have got to cut RJR below 50 percent. I am not going into a company where RJR has the majority of the shares." RJR agreed to take a step back and to lower its proposed stake. The leadership of both RJR and Targacept realized that RJR's stepping down to a minority role was necessary to give Targacept the best chance to succeed. Potential investors liked the fact that RJR had already assigned all the relevant IP wholly to Targacept rather than forcing the spinout to license patents and technologies and pay royalties to its parent, as is so often the practice.

Avoiding the Ties That Bind

In many spinouts, a strong tendency exists for the parent to covetously maintain majority ownership and board control. Despite RJR's loss of control, it seemed the right thing to do to give Targacept the best start. RJR CEO Schindler notes, "We decided to give up a lot of the ownership in order to increase the odds of success." Upon independence, only two of Targacept's seven board members remained RJR executives. The rest were experienced professionals with broad and deep ties to the biotechnology, pharmaceutical, and investor communities.

A spinout majority-owned and -controlled by its parent isn't really a spinout to most outside stakeholders, including key potential partners and investors. To them, it's more of a subsidiary in disguise. It's often in everyone's best interests for the parent to loosen its grip. Few savvy outsiders are likely to participate in a spinout in which they know their interests, and their investments, are subordinate to the whims of a potentially malingering corporate parent.

Relaxing the ties that bind (especially ownership and control) can create a bigger pie for everyone. By its full independence in August 2000, Targacept had raised $30.4 million in venture capital funding, one of the largest first rounds of VC funding for a biotechnology or pharmaceutical company that year. Securing these essential funds would have been more difficult, if not impossible, if Targacept had not been set forth on its own clearly independent path apart from RJR. The intangibles of independence were just as important. One scientist who joined the company noted, "I was intrigued by the notion of going to work for a promising biotech startup, but never in a million years would I have dreamed of working for a tobacco company."

With drug development well underway on a variety of fronts, Targacept raised its second round of funding in early 2003. In a seriously down market, both overall and for biotechnology, the $60 million infusion was one of the larger VC rounds that year. Targacept also renewed, and initiated new, co-development partnerships. It even embarked on making small, targeted acquisitions of compounds related to its own unique competencies and that complemented its own compounds under development. By 2004, drug development was well underway for compounds to treat memory and cognitive disorders, Alzheimer's disease, ADHD, anxiety and depression, ulcerative colitis, pain, and other ailments. A final twist was that Targacept even began to consider whether to spin out its own powerful and proprietary computational drug discovery technologies or instead keep them inside as core assets.

Bettering the Odds of Value Creation

A spinout is not always the right way to develop and commercialize innovation. Moreover, spinouts offer many challenges in implementation. Sometimes, just killing the nascent venture is the right thing to do; the costs of pursuing other options can exceed any likely benefits. Sometimes, licensing or selling the ideas and technologies can help a company realize some small returns. Other times, joint venturing can work—for example, if it's either an innovation asset in which the parent needs to maintain a stake, or even using a JV as a prelude and preparation for a full spinout. In Targacept's case, it was clear that these alternatives were either not feasible or offered little return for the effort and investment.

RJR's millions of dollars and years sunk into R&D put Targacept in a position of strength and credibility not available to a typical brand new startup. RJR helped Targacept launch itself as a promising spinout with established patents and technologies, world class researchers, and an experienced management team in place. But, just as important as all this nurturing, RJR realized when and how it should step back and set Targacept free.

After a spinout is set free, of course, there is no guarantee of success. As with any new business, it's free to flourish or fail on its own. But with better initial decisions and up-front planning, and with the right kind of nurturing throughout the process, the offspring is better equipped to try to stand and succeed as its own company. That's at least a very promising start.

Employing Spin Control

The bottom line is that, despite all the potential benefits of using spinouts to bring innovation to fruition, these theoretical advantages are far from enough to make a successful spinout. Would-be spinnovators must ask some critical questions up front, before launching into the spinout process:

-

Is the proposed spinout a non-core innovation asset, or is it too close to the core of the company to make sense to spin out as a separate firm?— In the overwhelming majority of cases, if it's close to the core, a spinout does not make sense and will result in more problems than benefits. Companies need to focus their attention and resources on nurturing and integrating these innovations within the parent company itself.

-

Does the spinout have a sufficiently strong standalone business case, or is it really just a premature idea or ill-formed concept with little hope of a functioning, independent business model?— If it can't stand on its own, it probably shouldn't be spun out. Nurturing it further internally might not make sense either, especially if it's a non-core innovation. If it is to proceed further, outside partners and investors need to be brought in to help lead it forward to the point where it can be spun out and stand on its own. This helps keep the spinout process from being distracting and detracting for the parent, which can keep a sharper focus on its core.

-

Is the spinout being done for sound strategic reasons or simply to pursue a quick financial boost (for example, to carve off debt and expenses or to get a rapid infusion of cash)?— Pursuit of short-term, quick-fix financial objectives through a spinout tend to cause long-term complications as the overall logic and structure of the spinout prove dubious and unsustainable over time.

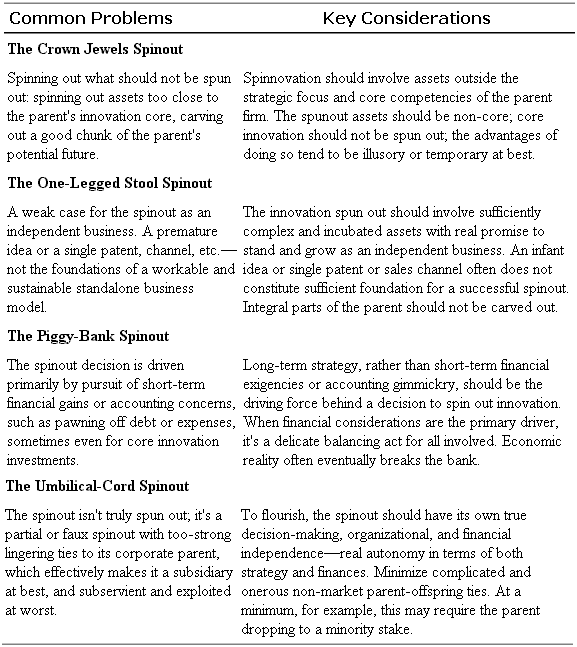

Beyond these critical decision points, one of the most common and most damaging implementation difficulties is when the parent firm simply doesn't know when and how to let go. Too much parenting and too many lingering parent-offspring ties can spoil, smother, or strangle a spinout, even before it really has its own shot at success (see Table 6-2).

Table 6-2. Spin Control

A Tale of Online Travel Agents

The overall logic and key questions for planning and implementing a spinout are similar for later-stage (post-commercialization) innovation. The dynamics of these types of spinout decisions are well illustrated in a tale of two online travel agents.

Travel has long been one of the largest and fastest-growing sectors of e-commerce. Through the Internet boom and bust, the online travel business continued to soar. Two of the first and fastest-growing leaders were Expedia, founded by Microsoft, and Travelocity, started by Sabre Holdings (itself an earlier spin-off from American Airlines's parent, AMR Holdings). In one case (Microsoft-Expedia), it made perfect sense to use a spinout to accelerate and enhance further innovation commercialization. In the other case (Sabre-Travelocity), the choice was not so clear and simple, and the process was more complicated.

Microsoft founded Expedia in 1996 as part of its general expansion from software into other online businesses. By 1998, Expedia had quickly grown to become one of the two online travel leaders. Despite Expedia's early success, Microsoft decided that it did not really make sense for it to be in the online travel agent business after all. Microsoft began the process of spinning out Expedia in November 1999, initially selling a 15 percent stake to the public. Soon after, Microsoft sold additional shares, bringing its ownership down to 70 percent. The divestiture was completed in 2001 when Microsoft sold its remaining majority stake for $1.5 billion to USA Interactive, joining it with Interactive's other online travel (Hotels.com, etc.) and retailing operations. As a more clear and core fit with the portfolio of its new parent, Expedia flourished. By 2002, Expedia accounted for almost half of all online gross travel bookings.

Expedia was a tremendously successful later-stage spinout. The online travel agent was an undervalued asset within its parent company, Microsoft. Despite its early success, it simply was not a core concern for Microsoft. There was little connection to Microsoft's other established businesses (operating systems and applications software), which with their huge profit margins and enormous cash flows overshadowed anything Expedia could hope to achieve. Expedia operated an innovative and fast-growing online travel business, but was still burning cash because of its continuing expansion. What to do? Given this entire context, it made perfect strategic sense for Microsoft to spin out Expedia. The spinout created considerable value for all the stakeholders involved.

With Travelocity, however, the story was a bit different. For some time, Sabre Holdings had denied any intent to spin out Travelocity. Unlike Microsoft, after all, Sabre was a leading IT-centered company that handled all sorts of travel-related e-commerce. Sabre executives frequently stressed that Travelocity was part of the core strategy for building the company's future web-based travel businesses. Sabre soon changed its tune, however. The lure of the dot-com spinout frenzy proved to be too great to resist. In March 2000, Sabre spun out Travelocity.com by turning it into a separately traded public company through a reverse merger with Preview Travel. Sabre retained a 70 percent ownership stake.

Travelocity quickly lost its early lead in the online-travel business. An aggressive Expedia became the leader, while Travelocity dropped to less than one-third of online gross bookings. To try to improve its lagging performance, Sabre was now ready to buy back all of Travelocity and, once again, make it a 100 percent–owned subsidiary. In attempting to reverse its spinout, Sabre executives noted that it simply made sense to fully combine Sabre and Travelocity in order to maximize their synergies, especially in core technology and operations.

Travelocity's investors and board balked at Sabre's initial low-ball buyback offer. In a scene too common to spin-ins, Travelocity shareholders filed class-action suits against both parent and spinout, challenging the buyback. Sabre upped its bid from $23 to $28, and a deal finally was struck. Travelocity once again became a wholly owned division of Sabre. Sabre's management reinstalled Travelocity as central to its future. Investment in Travelocity doubled in 2003, even as Sabre significantly cut back its investment in other areas.

The Right Spin

All these spinout examples illustrate the need to consider the specific context—not just the innovation itself, but especially the parent company: its unique strategy, resources, and the like. These cases also illustrate one of our main, overarching points in regard to all the different innovation options—there is no magic bullet, one-size-fits-all solution for all companies in all situations. Just because it might have made great sense for Microsoft to spin out Expedia does not necessarily mean that a Travelocity spinout made sense for Sabre.

The specific context and contingencies—especially the fit with a firm's core innovation—critically matter in deciding whether, when, and how to do a spinout, among all the other innovation options. Like all the other innovations fads and fashions discussed so far, spinouts can liberate and tremendously enhance innovation's value—if they're done right, and for the right reasons. They tend to work best as a supplement, not as a substitute, for core innovation.