5. The Selection of Appropriate Innovation Channels

“I dreamed a thousand new paths.... I woke and walked my old one.”

—Chinese proverb

Overview

Consider the opening quote in this chapter less one of guidance and more of a cautionary tale. Leaders, as noted in much greater detail in Chapter 9, “Leadership,” bring to reality that which they dream. And though there may not be a thousand paths discussed below, of the multiple paths available, too few are trod in most organizations at present.

This chapter is going to switch gears. Up until now, we’ve spoken about the changes that open innovation brings and argued its merits as a means of diversifying problem solving approaches, reducing false negatives, sharing and managing risk and thereby improving the overall productivity of your innovation engine, whether those innovations are for delineating new marketing campaigns, improving business strategy, or designing future products and services. But even solid portfolio arguments don’t always help those where the rubber hits the road. Many project workers and department supervisors see only the project. In fact, they often have no accountability for the overall performance of the portfolio but are keenly accountable for how well a given project is executed. They need to often make channel choices based on what’s best for the project or a portion of the project and so this chapter has been constrained to those arguments. To employ these different methods of innovation, someone has to choose which projects or parts of projects get executed inside, which get executed outside, and, if outside, by a commercial lab, a university, or a crowdsourcing platform.

These options are referred to, both here and elsewhere in the book as channels. Webster defines a channel as “a way, course, or direction of thought or action.” These channels will be courses of action leading to innovation. Much like distribution channels give producers a choice of how their product is distributed, innovation channels are the choices by which innovation skills are accessed, and apply to both internal efforts as well as external ones. As the whole notion of open innovation has flourished, there have been few attempts to provide practitioners with a concrete set of guidelines for how and when to select an innovation channel. At the conclusion of this chapter may be found a brief discussion of existing business literature on the topic and will provide you with sources for establishing a deeper foundation on the channels themselves and their distinctions.

The objective of this chapter is to classify ten distinct innovation channels, or mechanisms, both internal, or closed, and external, or open, by which innovation may be accomplished. Having defined these ten channels, you are then provided with a set of guidelines for the conditions under which each would be preferred. These guidelines provide channel selection by establishing for each project module an option of archetypes that characterize that specific module. This chapter complements the framework established in Chapter 3, “A New Innovation Framework.” Think of it as the lab manual or practicum for Chapter 3’s coverage of theory. As previously stated, the project modules, or challenges, are each distributed among the innovation channels. In this way, an overall project could conceivably be derived from the use of all ten, or certainly fewer, innovation channels.

Some of this choice making depends on what “kind” of corporation your company is and, to a considerable extent, on your corporation’s culture. For example, an organization dominated by a climate of secrecy is not going to make decisions about innovation channels as boldly as another company, even if it is in the same sector and even if it is making decisions about a similar type of task. That said, such cultures may find themselves disadvantaged as the benefits of “openness” often outweigh the risks associated with greater disclosure and transparency. You will note that for each archetype there is a “most preferred” innovation channel. These were constructed assuming a complete openness to new ways of innovating. However, fallback channels are also highlighted.

Other, sometimes pervasive, corporate culture and policy issues exist when your institution is founded on fundamentally different principles of both mission and organizational design, that is, not-for-profit organizations or government agencies as opposed to commercial corporations. In the case of not-for-profit foundations, their mission is to focus on social good rather than monetary return, which may lead to foundations making choices viewed as incompatible in a profit-seeking environment. Furthermore, because most not-for-profit organizations lack a permanent R&D staff, they are compelled to make innovation decisions differently than a for-profit neighbor. To avoid complicating the problem, assume an open mindedness to open innovation and a striving to some sort of evolving norm of diminished corporate isolation. For the most part, the specific recommendations assume a for-profit commercial venture. The adaptations for other organizational types are relatively straightforward after the process is laid out in detail.

Another objective is to find a way to rationally discuss this topic without a constant referral to the scale of the distributed tasks, even though scale could dominate the selection choices. It may be that, if an entire innovation program, say for the development of a new product, is to be moved through a single innovation channel, the channel choice would be substantially different than if each individual task within that program were to have independent innovation channel selections made for it. For the most part, assume that decisions are made about neither scale extreme—that is, not about the channel for an entire program nor for a single, simple work task. Think of a work module, or challenge, as referenced in Chapter 3; this is a unit of work that can be insourced or outsourced, and later reintegrated into a complete program of new product development, novel services, or governmental and regulatory policy.

A Channel Decision-Making Tool

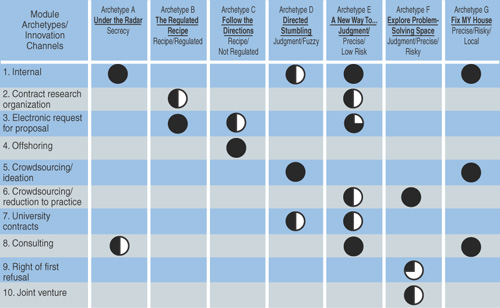

The final approach, presented here, was to define seven project archetypes and identify ten innovation channels. Each project archetype was then arrayed with the innovation channels, enabling the prioritization of the most suitable channels for each archetype. From this framework, a table with ten rows was constructed, one for each innovation channel and seven columns, one for each of the project archetypes. The chosen priorities are specified by using harvey balls (all black being most recommended) at the intersection of a given row and column. Where the solid black ball appears, this is the most recommended channel (specified by row) for that given archetype (specified by column). Less solid balls would suggest that this channel be considered after the first choice has failed or is deemed otherwise insufficient. Admittedly, there may be more channels that could be created by dividing the ones chosen or adding the ones overlooked. And not all projects are a perfect match to one of the seven archetypes presented. But it should make a good starting point for the projects and channels your organization pursues.

The definitions and details are probably necessary to make complete sense of Table 5.1. However, the table is presented first and then those details are filled in. You can thereby decide the extent to which those details are digested. You might use this to begin the “nuts and bolts” process of project dissection and allocation and or to simply understand the overall framework and use the definition portion of this chapter for reference.

Figure 5.1. Decision-Making Matrix for Selecting Appropriate Channels of Innovation Given a Project Modules’s Specific Archetype*

Innovation Channels

The ten channels listed below will cover most situations but are admittedly not all inclusive. No line exists for public-private partnerships, which themselves take on many forms. Further, additional rows could be added to the table by subdividing by funding mechanism. Even internal projects could be funded very differently by corporate proceeds, by taking on additional investors with project equity or by use of social impact bonds. For each, we’ve assumed the most common funding mechanism. The admitted limitations of a table with 70 cells also serves to illustrate the complexity of these choices in real-world practice. But this structure makes a good starting point and will guide most innovation channel decisions with reasonable efficiency and pragmatism.

Innovation Channel #1: Internal

Just as you would expect, this refers to innovating using the existing resources, namely people and equipment, within an organization. It’s the familiar “closed innovation” that required no name until open opportunities became more prevalent.

Innovation Channel #2: Contract Research Organization (CRO)

CROs usually focus on a well-defined range of specialties and capabilities. Examples of companies, and one example of the services they provide, would include Applied Analytical, which provides active pharmaceutical ingredient stability testing, Covance Labs, which provides toxicology studies, and Probion Analysis, which provides surface and solid state sample characterization. In many instances, they repeat a given type of research more frequently than a product innovator does. This gives them a competitive edge for conducting such studies. An agricultural chemistry innovator that markets specialized crop treatments might perform a certain environmental test one time for each of the three or four products that enter a later stage of research each year. On the other hand, a contract lab specializing in that same study might perform hundreds each year. Engagement with a CRO usually occurs after negotiating a contract.

Innovation Channel #3: Electronic Request for Proposals, e-RFP

Although the tasks will be carried out in this channel by a traditional research services unit—that is, a contract lab or a university—the contracting organization is identified via an electronic request for proposals. This enables the contracting group to access organizations they may be unaware of and to expand the range of alternatives prior to selection and agreement of terms. This channel is distinguished from the familiar RFP, or call for bids, which could be lumped in with the CRO channel, #2. At first glance it seems to be an artificial divide. Isn’t it just a matter of scale? However, as often heard in the complexity sciences, “more really is different.” There have been recent, unique service providers in this arena, for example, Nine Sigma, that have helped expand the search so significantly via the Internet that they enable many new connections and enhance the innovation network in ways that didn’t exist in historic “bidding.”

Innovation Channel #4: Off-Shoring

The distinctions between this channel and the CRO, channel #2, may also seem a bit contrived, but it is useful to recognize that for certain types of tasks, there is a legitimate motivation to get it done at a low cost. This rationale is usually captured by the term off-shoring versus outsourcing, because the off-shoring most often refers to the placement of the work in countries where labor costs are significantly lower. A variation within this channel is illustrated by the company oDesk, a business that assembles workers around the world to engage in tasks that can be fully digitized and communicated via computer connections. This straightforward means of engagement reduces not only the direct labor costs but also reduces the transaction costs of contracting and negotiating.

Innovation Channel #5: Crowdsourcing, Ideation

Many times the innovation channel described here, and in channel #6, as “crowdsourcing” is not divided into subcategories. This channel is subdivided because some types of crowdsourcing are more appropriate to some archetypes than other types of crowdsourcing. Channel #5 refers to the broadcasting of challenges to a wide audience but with the expectation that the solving audience would respond with only their ideas or a theoretical justification for why their approach should work. This ideation effort can be as simple as the “jams” that have been popularized to broadly solicit ideas, a global brainstorming if you will. Or it can be as complex as proposed new mechanisms for disease treatment requiring exhaustively cross-referenced research papers. Either way, the important distinction from #6 is that Channel #5 does not require anything by way of equipment or laboratory facilities; its work product is primarily intellectual in nature.

Innovation Channel #6: Crowdsourcing/Reduction to Practice

This second crowdsourcing channel assumes that the solving community will also conduct the studies required for “reduction to practice.” The solving community members to whom the challenge is broadcast are expected to conduct appropriate experiments and demonstrate the viability of their solutions. Sometimes the act of “reducing to practice” requires enormous resources—think of the Ansari X Prize in which the submitters had to “build and launch a spacecraft capable of carrying three people to 100 kilometers above the earth’s surface, twice within two weeks!”1 (Exclamation point added, duly.) Usually “reduction to practice crowdsourcing” requires far more modest resources—for example, the Challenges typically posted on InnoCentive. And, sometimes the resources are little different from the tools required to access the Challenge—for example, the creation of computer code for an open source software package or for an algorithmic challenge posed by Topcoder. (That is, the very tool by which you accessed the website, your computer, can probably, with some software additions, provide you with the laboratory under which you can solve the problems posed.)

Innovation Channel #7: University Contracts

This channel is considered distinct from either of the outsourcing channels associated with CROs or off-shoring for a variety of reasons. The work is often conducted as part of graduate student thesis efforts, with special IP and publication issues, and more important, the efforts themselves provide affiliation with some of the most respected and trustworthy brands in the world: Harvard, Stanford, INSEAD, and so forth. These distinctive characteristics of academia are a part of why this channel may be chosen, under what conditions it is appropriate, and how results should be managed.

Innovation Channel #8: Consulting

Other than the channel for internal innovation, this may be the channel with the longest history and is self-explanatory.

Innovation Channel #9: Right of First Refusal

“Right of first refusal,” seems less of an innovation channel than a contract term. Admittedly true. But it offers a unique way to manage risk—by paying for “fewer” rights upfront in exchange for the right to negotiate for greater IP, at a later date, after risks have been reduced by experimental outcomes. For this reason, it should be made part of explicit decision making and not treated as a contractual after-thought.

Innovation Channel #10: Joint Venture

This channel is usually employed when entities, which usually do not compete with each other, may both benefit from the outcomes of an innovation endeavor and want to share risks, costs, and of course, financially attractive outcomes. It is used historically to enter new geographies—often combining one firm’s knowledge of the local market with another’s knowledge of the technology. It is used too infrequently for portfolio management and balancing. It offers a chance for constrained budgets to explore more alternatives as costs are split between two partners. Yes, rewards have to be shared also—and this is sometimes dissuasive. But by sharing uncertain outcomes across more projects, the expected value of the portfolio can usually be realized with its variance being simultaneously reduced.

To define each archetype as succinctly as possible, some terms need to be introduced along with existing descriptors in a specific way. Each of the terms used in constructing the archetypes, which identify the central characteristics of different types of problems, are defined.

Terms Used in Defining Archetypess

Secrecy: There are circumstances in which the project’s solution and the solving techniques must be confidential. In addition, sometimes reasons exist for avoiding even the disclosure that this product or project is of interest; that is, you don’t want anyone, and especially competitors, knowing what you are working on, or whether you are close to a solution. The innovation channels must be chosen to minimize exposure.

Recipe: Certain tasks, in an overall innovation endeavor, may be characterized by the presence of a “recipe” that can be followed. The presence of a recipe does not preclude that it is being applied to something of an incredibly ingenious nature. Even a breakthrough cure for cancer needs to be shown to be stable under anticipated storage conditions. That stability measurement may follow a tightly prescribed protocol or recipe.

Regulated: Many research tasks fall under the regulatory purview of professional societies, or, most often, government agencies. In those cases, special consideration must be given not only to HOW tasks are carried out but at times even by WHOM. Some regulators require certification of the individuals, labs or institutes conducting the work.

Judgment: This is a task in which no recipe can be followed. It is something that may require points of judgment and complex choice making, usually predicated on some level of expertise or ingenuity. This would also include efforts for which invention must occur on the project’s critical path.

Fuzzy: Unfortunately defies attempts at description. Some project tasks have a well-defined outcome, describable in advance, whereas others fall into the old category of “I’ll know it when I see it.” It is these latter types of investigations that are called fuzzy.

Precise: This doesn’t refer to the integrity or degree of the measurements but to the specifiability of the outcome. Can you describe, precisely, what that outcome will look like even before it is actually known? This term is used in opposition to the term fuzzy.

Risky: Risky projects are those that have a low probability of success but which require substantial resources for resolution. These two elements, probability and expense, play off one another. For example, the lower the expense for resolution, the lower probability of success you can tolerate. In other words, if you’re not spending much money, if you’re not “at risk,” you can accept that the likely outcome is failure. A project that doesn’t require extraordinary resources and is likely to succeed in a relatively few number of attempts is defined as low risk.

Another way to look at risky projects would be to realize that their “solution surface” is rugged, complex, and difficult to explore. A solution surface is defined as the goodness of outcome for any given experiment involving the adjustment of multiple experimental parameters. If the optimal solution, or near-optimal solution, must be found on that surface, the project is likely high risk. If the surface is scattered with many “good enough” solutions, the project is likely low risk.

Local: Although all projects require some sort of domain knowledge, that is, computer programming, engineering, physics, compensation strategies, bookkeeping, and so on, they may not require knowledge specific to the seeker’s environment. However, some solutions are useful only when they comply with the demands of a specific environment, an environment not easily replicated elsewhere.

Project Module Archetypes

With the project elements defined, you can now combine these specific terms to create the archetypes and discuss which channel is appropriate for each and which channels may act as fallback positions, owing to nuances of the project or failure to achieve results on first attempts. The text that describes each of the archetype scenarios can serve to clarify what you can probably already infer from a studious examination of Table 5.1.

Archetype A: “Under the Radar” Descriptors: Secrecy

The first archetype is dominated by the need for secrecy. That need trumps other project properties and almost solely determines channel selection. In this instance, it is important not only that the solution and the approach to problem solving be kept confidential but also that the problem and the organization’s pursuit of a solution is confidential. An example might be a decision to investigate and commercialize a new technology.

The authors issue a caveat: Confidentiality is often used as a rationale for explaining why a company cannot more fully engage in the use of open innovation. This is more often than not a retreat to territory that is hard to debate. The need for confidentiality is often over-fretted about and overstated. The reality is that far less is disclosed than you might imagine. What seems obvious to the people working intently on a given approach is actually much less obvious to even domain experts who are not actively pursuing that particular approach. Although hard to actually quantify in practice, it is difficult, based on the authors’ research experience, to imagine that any more than ten percent of the tasks undertaken actually belongs to this archetype.

When secrecy does dominate, and this is the appropriate archetype to consider, using internal resources is the channel of choice. If it is necessary to involve those outside the organization, then the fewer involved, the better. For this reason, a secondary channel would be consulting, where disclosure is limited, often times to one person, and at most, usually a small handful.

Archetype B: “The Regulated Recipe” Descriptors: Recipe, Regulated

The second archetype is one for which there is external regulation and for which it is appropriate to employ a recipe, a protocol that can readily be followed by reasonably trained workers. A good example would be stability studies carried out on new pharmaceutical agents.

The most appropriate channel to use for project modules fitting this archetype is a contract research organization. In this circumstance, a CRO is chosen because its tendency to specialize makes it better prepared to deal with regulatory requirements. Also the frequency with which the CROs execute specialized studies enables them to more appropriately respond to regulatory queries. We have shown a preference for the electronic request for proposal (e-RFP) preceding the CRO engagement because the number of available and properly skilled CROs is usually much greater than any organization’s regular list of CRO contacts. The use of the e-RFP may also enable the seeker to find the most appropriate overlap of individual and unusual skill sets.

Archetype C: “Follow the Directions” Descriptors: Recipe, Not Regulated

The third archetype resembles the second in that a protocol is available to which the execution tasks can adhere. But it differs from the second archetype because there is no regulatory oversight. An example would be a standardized test of tensile strength or the preparation of circuit board prototypes. Thus the emphasis is on the quality of the results, as opposed to the regulatory-mandated activities inherent in the procedure. It is also less crucial that the organization conducting the study be well known to regulatory authorities or that its track record has been proven, or that an audit trail needs be rigorously established if future inspections occur. This relaxing of regulatory concerns can enable you to be more sensitive to costs and less sensitive to reputation. The preferred channel for this archetype is off-shoring.

Where the work being conducted requires some specialized facility, a contractual relationship with an offshore partner is usually best. Where the work requires no specialized facility and can be done “from home,” then a distributed work system such as oDesk2 is appropriate. As an alternative, the use of an e-RFP process is recommended although that process will be used primarily to find appropriately low cost providers. If the need were significant for novel approaches, in-progress judgments, or rare capabilities, a different archetype would have been assigned.

Archetype D: “Directed Stumbling” Descriptors: Judgment, Fuzzy

The fourth archetype is characterized first by the absence of a recipe that may be followed. It requires that you make judgments as the work evolves, and at times you need to achieve full-out, inline invention. An example might be a business plan definition or finding a new electricity conducting polymer. Archetype D is further focused on those projects for which the outcome may not be declared clearly in advance—for which the outcome is fuzzy. Over the course of work on such a project, new ideas will be generated and tested, and a solution will emerge without having been predefined. This is the project challenge where you will know the answer when you see it, and much stumbling around will occur enroute to that answer.

The first channel of choice for this archetype is to crowdsource an idea or a theoretical solution. The use of ideas and theoretical solutions minimizes the overall degree of wasted effort and enables the project owner to try out many possibilities before selecting one that appears to offer promise. Crowdsourcing also enables these multiple approaches to be proposed in parallel, and with the appropriate reward structures enabling the ultimate benefactor to pay only for what seems promising and to not pay for the dead-end ventures, which are inevitable when a project has that “stumbling around,” fuzzy quality.

As a backup to the crowdsourcing approach, again the use of internal resources that enable you to iteratively “stumble around” and ask, “Does this look promising?” is recommended.

A third channel of choice might be contracting with a university research group. Such open-ended endeavors are more valued in the academic environment, not only for the graduate student training ripe within, but also, the ability to spawn future avenues of research, which may, in some cases, not be viewed as competitively advantageous by the commercial grant provider.

Archetype E: “A New Way To...” Descriptors: Judgment, Precise, Low Risk

The fifth archetype shares that need for judgment with the fourth archetype. But in this archetype, the nature of the solution can be defined in advance. A good example of a solution that can be defined in advance would be seeking a means of fusing two different materials together. You are likely to succeed, but the task could still require several judgments and the solid material at the end is a clear indicator of success. And finally, this archetype is characterized as being low risk.

Because this archetype is characterized by low risk—and hence calls for a somewhat straightforward application of the appropriate skill sets—the first choices of innovation channels are internal execution, assuming the internal organization is still packed with domain experts, and engagement of a skilled consultant. These channels enable the seeking organization to identify the skill sets required to solve the problem and apply them efficiently. If there are other considerations like capacity, that is, “We just don’t have time to do it ourselves,” then CROs, either with or without an electronic request for proposals, may be used.

As a third priority, many universities are willing to engage in low-risk execution where the requirement for judgment can be beneficial in the training of students. And also as a third priority, may be the option to crowdsource a reduction to a practice solution. In this instance, the diversity associated with crowdsourcing may not be demanded for the exploration of solution space but rather to sample a variety of judgments, all likely leading to the desired outcome. Crowdsourcing may also be uniquely advantageous where the low transaction costs associated with engaging “a crowd” are more attractive than the higher transaction costs associated with negotiating and contracting with universities and CROs.

Archetype F: “Explore Problem-Solving Space” Descriptors: Judgment, Precise, Risky

The sixth archetype, like the fifth, will also require judgment during execution and possesses a precisely defined outcome. But the likelihood of arriving at a satisfactory answer is low. Thus, this is a “risky” endeavor. An example might be to develop a new chemical synthesis—the target molecule being defined precisely, while the intermediate molecular structures and processes are entirely open-ended and subject to extremely complex rules of selection, and even intuitive leaps. In this instance, the clearly preferred channel is to crowdsource with a demonstrated reduction to practice. That serves not only to tap a crowd’s diversity but to offload the execution risk and the likely potential for technical failure.

Here the diversity of the crowd enables solution space to be widely sampled in parallel, ensuring that the overall investigation does not bog down on the necessity of conserving resources and having encountered an area of solution space that looks deceivingly encouraging.

As a fallback, the use of joint ventures is recommended, where expenses and risks are shared. As a final option, contracting is suggested, under terms where the cost of failure can be minimized by purchasing only a right of first refusal up front.

It is not recommend that risky ventures be conducted solely in-house, although they usually are. In that case, the costs associated with failure are borne exclusively by the investigating organization. And the domain biases—which come with expertise, as explained in Chapter 4, “The Long Tail of Expertise,”—constrain the ability to effectively search broadly for solutions.

Archetype G: “Fix MY House” Descriptors: Judgment, Precise, Risky, Local

The seventh, and final, archetype contains all the elements present in the sixth—judgment, outcome precision, and riskiness, plus a fourth element: local knowledge. The demand for local knowledge is a substantial constraint on the use of open innovation channels because that local knowledge is intrinsic only to the closed channel—by definition. This archetype is appropriate when you need to know the specific characteristics of a niche customer base to improve service or the exact configuration of the production line to fix a problem that has arisen or where the presence of domain knowledge becomes of vanishing importance. So, in spite of the adverse consequences of centrally holding the risk and paying for all the likely failures, it is necessary to once again recommend internal research as the preferred channel. Some diversification can be achieved by engaging consultants on-site where they may quickly come up to speed for the local conditions and unique configurations that the solution must address.

A final alternative for this archetype, on par with internal efforts under some conditions, is to consider crowdsourcing solutions in a way that acknowledges the inability to disclose the local knowledge, but at least widely explores the applicability of domain knowledge. This last alternative channel is a reminder that there are times when your failure to solve a local problem is, actually, a failure to explore all the realms of domain knowledge that might be brought to bear on that local problem.

As acknowledged earlier, the channel recommendations are undoubtedly incomplete; though, a practical and practicable middle ground is presented. On the one hand, you need to consider enough elements of a decision to differentiate among an increasing number of innovation channel options. At the same time, you must narrow your selection criteria to few enough elements so that the problem does not combinatorially “explode” without a concurrent increase in utility.

Can you find a particular need that doesn’t fit one of the archetypes? Probably. Can you find a particular channel that doesn’t fit those described? Probably. But if you can cover 80 percent or 90 percent of the real-world situations, then you will have accomplished your task. The seven archetypes and the ten channels can provide guidance for the few examples that do not fit within this construct—and at the same time, an understanding of the principles involved in arriving at this formulation can also enable you to make adjustments, as necessary, to fit a future circumstance.

As covered in the overview, this chapter was directed to the project leaders, the department supervisors, and the technologists, artists, and scientists charged with making innovation actually happen. The recommended channels are best for the unit of work that has been modularized and defined. But, practice also invokes a larger benefit for the organization at large. A portfolio of innovation projects, properly channeled will produce the risk management and overall improved organizational performance argued for many times in this text.

But these channel recommendations hardly stand in strict isolation. One important paper touching on topic of multiple channels, and choosing between them, was published in 2008 by Roberto Verganti and Gary Pisano at Harvard Business School; the paper includes an outstanding analysis of selected channel categories, clusters of channels that share properties of openness or closedness, and flat or hierarchal authority structures. Verganti and Pisano define these categories and their distinctive properties and applications.3 The following year, Eric Bonabeau published a excellent piece on “Decisions 2.0,” in the Sloan Management Review. That work categorizes open platforms according to type of innovation function, types of questions asked, and explores the important issue of diversity versus expertise.4 And in 2010, Carliss Baldwin and Eric von Hippel, examined three basic modalities of innovation: single user (imagine designing a custom inline skateboard for yourself); producer (the most classic approach, an innovation arising primarily from a closed system and made available for sale by the innovator); and open collaboration (the most familiar instance being open-source software). The three modalities were linked by a mathematical model that allowed the viability of each to be assessed across a matrix of communication costs (the costs of sharing and exchanging information) and design costs (the costs of coming up with something unlike the current choices).5 For all innovators, these works are to be highly recommended and the real-world impact of professor Pisano’s analysis are an integral part of the NASA case study at the end of Chapter 3.

The Challenge Driven Enterprise

At this halfway point in the book, you have learned predominantly about why, and in what way, a highly connected future can alter your innovation processes. Chapter 2, “The Future of Value Creation,” noted that the changes in store for innovation were predicated upon the design logic of the firm and that vertical disintegration was not limited to innovation functions. Chapter 3 telegraphed some of ways in which the internal innovation activities and roles need to change, under a different framework for innovation and the management of distributed projects. The subsequent chapters focus more on the broader organizational changes and the processes necessary to better compete in the flat world. You see the shift from Challenge Driven Innovation to the organizational strategies and practices that can best achieve it: the Challenge Driven Enterprise.

Case Study: How Eli Lilly and Company Is Changing from a Closed Company to an Open Network to Provide Medicines for the Twenty-First Century

At a Brookings Institution Conference in 2010, keynote speaker John Lechleiter, Eli Lilly’s CEO and Chairman, stated:

The Lilly I joined as a scientist over 30 years ago was a ‘fully integrated pharmaceutical company’—or FIPCo—that owned the entire value chain from an idea in a researcher’s lab to a pill in a patient’s medicine chest. As we entered the 21st century, Lilly adopted a new model—a ‘fully integrated pharmaceutical network.’ This FIPNet still stresses the integration aspect...with Lilly assembling and orchestrating the network...but more and more of the pieces are linked through partnerships, alliances, and other relationships and transactions...rather than always through outright ownership. A well-developed FIPNet allows us to cast a wider net—for ideas, for molecules, for talent, and for resources. In the process, we can greatly expand the pool of opportunity. We can leverage our financial resources by sharing investment, risk, and reward. This wider net is global; so, not surprisingly, we’re doing more work in China and India, tapping into the vast intellectual capital in those countries.

—John C. Lechleiter, PhDChairman, President and Chief Executive Officer, Eli Lilly and Company6

Now rewind the clock a few years. The moniker FIPCo for Fully Integrated Pharmaceutical Company arose in the late 1990s. It served both to define what the largest companies in the pharmaceutical industry were—and what they were not. It was a distinction—and one that you could be proud of. FIPCos did it all: from the discovery of drug candidates, to their development, to their manufacturing, to their marketing, to their sales and delivery. Biotechs were useful; but, if their products were going to reach patients, they were either sold to a FIPCo or the biotech “grew up” into a FIPCo, such as the legendary Genentech and Amgen.

At Eli Lilly & Co., all the executives understood the value of being a FIPCo and what that meant. But as a strategic intention, it fell short. It didn’t differentiate Lilly from its competitors and, as the world changed, it seemed less relevant. FIPCos were relying on biotechs to source new pipeline candidates. On the other end of the spectrum, they were contracting sales forces to generate revenue. Recognizing the degree to which key strategic decisions deviated from the organizational framework of a FIPCo, Lilly coined the term FIPNet, meaning Fully Integrated Pharmaceutical Network, suggesting the merits of the integrated process but acknowledging that it could be a network, not a single corporate entity. Actually, that it should at some point in the future be a network—for reasons of better managing a risky business and ensuring continued advancements by attracting resources and ideas from around the world. As this notion was unpacked, it began to not only better address a changing world, but was also a source of freedom in the way organizational structures and capabilities were accessed.

By the year 2006, when the term FIPNet came into corporate usage, the transformation from a “Co” to a “Net” was already underway. Lilly had realized that drug development efficiency was hampered by the high ratio of fixed to variable costs and had begun changing this. Lilly executives realized that they had to attract external resources and had “spun out” entities like InnoCentive (a crowdsourcing model for complex problem solving) and YourEncore (in partnership with Procter & Gamble, a consulting firm providing specialized resources for a retiree population), while creating new internal capabilities to orchestrate the external work, such as Chorus—which worked externally to develop clinical study designs and protocols and then orchestrated their execution by external research centers.

According to Peter Johnson, Lilly’s VP of Strategy, “The FIPCo (Fully Integrated Pharmaceutical Company) was a description of the past. It lacked a visionary component, and the world was changing too fast. Every time we felt that we had made a smart, adaptive move, it seemed ‘anti-FIPCo.’ We needed a simple concept that provided strategic alignment and a ‘northstar’ for choice making. Becoming a FIPNet (Fully Integrated Pharmaceutical Network), even as the term was in the process of being defined, allowed many executives to make distinctions and work in greater harmony. It meant some divestitures made sense; it meant that contracting had a real role alongside hiring. It also meant that external talent needed to be nurtured just as internal talent did—that renting sometimes made more sense than owning. Finally, it meant that, at times, orchestration trumped management as a tool for getting stuff done.”

Since the strategic declaration that it would “orchestrate the Fully Integrated Pharmaceutical Network” as opposed to “build and maintain the Fully Integrated Pharmaceutical Company,” Lilly has taken many bold steps toward the realization of that goal. In 2007, Lilly divested the entire toxicology function. Toxicology is the study of the bodies response to introduced chemical substances, whether they originate in the food chain, environmental sources, or the medicines used to treat disease. This wasn’t simply following the adage, “Sell the mailroom.” Toxicology, as a crucial R&D capability, had long been viewed as core to the company’s operations and a strategic advantage. But now, that view was seen as right for a different era. There never was and never would be unanimous agreement in favor of such a radical step; good arguments abound on both sides. But the truth was that as contract services and marketplaces in complex medicinal research functions became more and more available and globalized, some capabilities were more efficiently contracted (and sustained) externally. And the FIPNet vision helped in making the call.

The transformation continues to this day. In 2010, it was reported that Lilly and other partners would create up to $750 million in various external venture capital funds to identify new drug candidates and develop them through clinical proof of concept. Lilly would directly invest up to $50 million in each of three geographically distinct funds as a 20 percent contributor. Of course, its contributions go way beyond the capital infusion. Its tacit know-how for drug development and the capabilities of development platforms such as Chorus7 could make the productivity of these funds more impressive than their size alone.

It won’t be easy for other companies to follow this network model. Years of managerial development do not necessarily produce the essential skills of orchestration. And the organizational and cultural challenges are daunting. The divestiture of functions, the retraining of individuals for new ways to work and contribute, and that risk sharing means reward sharing in the end will pose significant barriers. Both vision and courageous leadership will be required to make the jump.