6. The Challenge Driven Enterprise

“Every day you may make progress. Every step may be fruitful. Yet there will stretch out before you an ever-lengthening, ever-ascending, ever-improving path. You know you will never get to the end of the journey. But this, so far from discouraging, only adds to the joy and glory of the climb.”

—Sir Winston Churchill in Painting as a Pastime

Overview

Imagine every department with a clear picture of its needs, options, and work in process. Imagine each decision being made by managers bound to driving the optimal outcome regardless of where the resources reside. Imagine the vibrancy of an organization whose singular focus is driving performance excellence and not measuring success by patents issued, full-time headcount, or the size of its R&D budget. In such an organization, the CEOs agenda is that of the investor: How can the firm drive the best returns? The CFO not only tracks the business, he also manages risk and opportunity by measuring the effectiveness of all parts of the organization to deliver against its goals—in business and economic terms—with innovation held to the same performance standards as every other part of the organization.

Whether it is marketing, information technology, product development, or manufacturing, every department understands its problems and challenges and its various channels for problem solving, and has the skills to manage the process effectively, take action, and create solutions to drive enterprise value.

Too often organizations measure their success by % of sales spent on R&D, how many patents they own, or whether the leading academics in their fields are on retainer. However, in today’s economy, these should all matter much less to the management of the organization or to the shareholders than whether they can get a new product to market before the competition and dominate the category or whether resources are being managed to ensure the firm can aggressively pursue new business opportunities when they emerge. The prevailing mentality of most established businesses slows, if not discourages, innovation while increasing its costs. Ultimately the shareholders pay the price.

Challenge Driven Innovation represents a dramatic evolution in enabling more effective, efficient, and predictable innovation. And our experience with businesses suggests there is enormous benefit simply in managers and employees better defining and managing their own problems. The transformational change, however, is accomplished through the remaking of the organization into the Challenge Driven Enterprise, where the most difficult problems can be solved, effort is aligned with strategic goals, all talent inside and outside of the organization is brought to bear to deliver on the mission, and sustained performance improvement is possible.

The Challenge Driven Enterprise represents a new vision with far-reaching implications that can improve the speed, agility, and efficiency of business. It enables new modes of innovation while creating the flexibility to capitalize on new business opportunities. Industry leaders will be those that successfully apply these concepts universally, from business strategy to the manufacturing plant floor.

Li & Fung Ltd, the Hong Kong-based trading company, reinvented itself as a highly dynamic virtual company. It provides an outstanding example of the power of this approach (see Li & Fung Case Study in Chapter 2, “The Future of Value Creation”) and provides an excellent glimpse into the future. Meanwhile, new firms such as TopCoder, LiveOps, and InnoCentive are emerging that enable many of the principles outlined in this book. And they are already helping to redefine competitiveness for hundreds of the world’s top companies.

This chapter defines a Challenge, explores why it works, discusses mechanisms by which a challenge-based approach can be implemented as a core process, and offers a number of select examples. Then the Challenge Driven Enterprise is formally defined, which provides an end-state vision for organizations to drive innovation, agility, and better economics for doing business in the 21st century.

What Is a Challenge?

Too many organizations struggle to define their problems and goals, much less to innovate with the precision and efficiency needed to compete in the world today. Whether building better business strategies or designing new technologies to dominate a market, traditional business practices are no longer sufficient. Nowhere is this truer than in large corporations where years of accumulated standard operating procedures, poorly aligned incentives, ever-increasing bureaucracy, and entrenched culture work together to ensure that increasingly expensive and mediocre innovation is the best they can do. The existing systems are failing and firms are in desperate need of new methods to improve responsiveness and competitiveness.

Dictionary.com defines a “challenge” as “a summons to engage in any contest” or as “a job or undertaking that is stimulating to one engaged in it.” However, it is much more. Well-constructed “challenges” are an astonishingly powerful and uniquely effective tool for focusing the energies of multitudes of creative, inventive, talented audiences on the important problems facing organizations, nations, and the planet on which we live. These audiences can be employees, customers, partners, and a planet of resources.

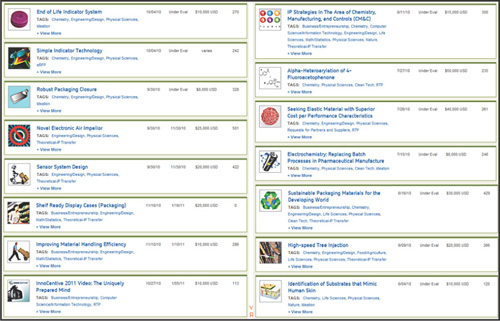

The Challenge is core to InnoCentive’s business, and its power has been on display now for several years. We see early glimpses of this approach throughout history, well before InnoCentive’s founding. Striking examples of its use range from the Longitude Prize offered by British Parliament in the 1700s to the Ortiz Prize that induced Charles Lindbergh to cross the Atlantic. It has been shown to have broad and general applicability. InnoCentive has more experience with Challenges than any organization in the world and provides an intriguing sampling of the potential of Challenges in areas as diverse as business entrepreneurship, life sciences, mathematics, and manufacturing. Challenges can deliver breakthrough strategies or highly technical solutions and apply to every business function and every type of problem, large and small, strategic and tactical. A random sampling of InnoCentive Challenges is provided in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1. How InnoCentive Challenges address a multitude of problems

Source: InnoCentive

But why does it work? We first began to understand the Challenge as a powerful business tool a few short years ago. It was at this time that a number of key concepts were beginning to converge, namely that a Challenge exhibits three important properties. They provide:

• Fundamental unit of problem solving;

• Better way to organize work; and

• Powerful strategy tool.

Taken together, these properties position the Challenge at the center of Challenge Driven Innovation (the process) as well as what we call the Challenge Driven Enterprise (a business underpinned by the process), whether for business strategy, driving operational efficiency, or R&D. Let’s explore each of these.

I The Fundamental Unit of Problem Solving

Albert Einstein once famously said “If I were given one hour to save the planet, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute resolving it.” This provocative statement recognizes the importance of understanding the context of a need, articulating requirements clearly, and applying precision in defining outcomes and goals. Stephen Shapiro, a popular writer and public speaker on the topic of innovation, reflecting on Einstein’s words added that in fact “Most companies spend 60 minutes of their time finding solutions to problems that just don’t matter.” Shapiro’s observation is true more than most would admit.

All problems, big or small, must be clearly defined and tied to the strategic goals of organizations. Are some problems too big? Quite the contrary. We have learned at InnoCentive that for the big problems, it is essential to systematically refine them into more focused questions and ultimately to well-defined Challenges. Nearly any outcome focused activity may be cast as a well-defined Challenge or system of Challenges.

Focusing the energy of organizations and even an entire human population on problem solving has always been possible but requires process and tools to do so effectively and at scale. And generally the approaches employed by business have been uneven and imprecise. Rigorous and disciplined construction of Challenges focuses that human energy to drive results in ways never before possible.

Harvard Business School Professor Karim Lakhani and others have consistently confirmed the critical importance of defining the problem, the key to InnoCentive’s challenge-based model and its success. The problems must invite diverse participation because you want potential solutions for engineering problems to come not just from engineers, but from entrepreneurs, mechanics, and chemists. At the same time, potential problem solvers must be focused on the specific task at hand with as much context as possible. As you can imagine, getting this right is incredibly important to sustaining high solution rates.

Paul Carlile is a professor from Boston University with an unusual background in both social and computer science and a gift for seeing the world through a system’s lens. In 2009, Paul introduced InnoCentive and the authors to the concept of Boundary Objects,1 which sociologists use to describe powerful compartments of information that are both well defined and that translate naturally across communities and cultures. Examples of boundary objects, discussed briefly in Part I of the book, in the real world would include Laws and Contracts, well defined by their very nature, universally understood, and vital to modern society. InnoCentive Challenges are boundary objects in every sense of the term. Challenges articulate the need, describe the problem, specify success criteria, and establish the inducements. The inducement is a critically important component because it telegraphs a tangible and measurable value to the world. The best Challenges are universal and thus universally understood.

It is the precision and care taken to define the Challenges that elevate them to the status of true boundary objects. A hallmark is the understanding of how to manage the process to truly engage a highly distributed network and focus them to drive successful outcomes. Well-defined Challenges must ask the right questions. Practitioners must be meticulously attentive to detail or else they cannot understand and articulate problems in a concise way. Well-defined Challenges anticipate the audience and the conditions for effective engagement. Does the Challenge call for a new idea or a new business plan? Is the Challenge seeking scientific discovery or simply new approaches? Do you want the world to give you the idea or do you want someone to demonstrate something physical? Challenges must also anticipate the cultural and legal realities of the world (for example, is intellectual property an issue?).

It is important to note that a significant amount of the effort spent on creation, invention, and strategy in many organizations today is wasted, lacking any real precision or definition. How many IT programs over the years lose their original focus and suffer from scope re-definition to the point they look nothing like the original intent? Nor can they be tied to key drivers of the business—and we wonder how that happened. How many marketing programs fail to define measurable analytics and resist any attempt at defining ROI? How many strategies and new product initiatives are undertaken due to the charisma of the sponsor or the allure of a sexy new space rather than a critical assessment of the opportunity, feasibility of approaches, clear statement of success criteria, benefits, and risks? How many R&D programs have no discernable business sponsorship or tie to business plans or future revenue and earnings? Disappointingly, most of our firms are not operating with this precision or clarity.

In his famous speech on May 25th, 1961, President Kennedy said “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” He was challenging a country to put a man on the moon in 10 years, a seemingly impossible task, but one that united a people. Organizations focused on exceedingly well-defined goals, coupled with innovative empowerment structures, will enable stunning outcomes inside and outside of traditional management paradigms.

II A Better Way to Organize Work

There are many kinds of work. There’s work on the assembly line, analyzing water for impurities, delivering newspapers, and fighting wars. And loosely speaking, Challenges may have a role to play in all these kinds of activities. And there is a different kind of more intellectual work requiring more creativity and invention, whereby a need is identified and a solution sought. Examples include development of a marketing strategy, a new plastic material for manufacturing, or an innovative approach to engaging customers. In this latter kind of work, well-defined challenges represent a powerful tool for organizing human activity and motivating innovative outcomes.

Organizations have spent years defining efficient organizational forms, writing Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), crafting job descriptions, and even developing robust platforms for planning and tracking work. And they are becoming more efficient. Use of contract labor and outsourcing of work, even whole functions, is more commonplace than ever. These approaches have often improved the bottom lines of businesses by increasing flexibility, lowering costs, and enabling projects to be accelerated. However with notable exceptions, these exercises in efficiency and shifting labor costs have done little to fundamentally change the rules of the game—to create anything like a “step change” in business performance and breakthrugh innovation. In most instances, the 20th-century approach is essentially institutionalized resource planning and labor arbitrage that is simply commoditizing work and trading high cost labor for lower cost alternatives. It is not creating a unique competitive advantage. And it is certainly not tapping the creative capacity of organizations and the world to innovate. In some cases, it has actually achieved the opposite effect. Consider how many companies arguably lost their innovative edge by focusing so singularly on cost reduction that they lost the very resources and capabilities needed to be competitive over time (for example, Dell, General Motors). Some even created their next-generation competition by turning their suppliers and partners into the only true sources of innovation (for example, semiconductor). Clearly a less simplistic and more intriguing model for remaining both competitive and innovative must exist.

If you are to fundamentally transform the economics of businesses, while achieving heightened levels of innovation performance, it is clear that a substantially more scalable approach will be required. Such an approach would leverage network efficiencies, better economics, and modern technology. Organizations will open up their processes, inviting in thousands or millions of individuals and organizations to participate in their business processes.

Thanks to the Internet, you can now engage a global platform in your problem solving and use this platform to deliver against your goals with precision and consistency, while better leveraging your in-house resources.

But how can you engage this nearly unbounded marketplace of knowledge workers, creative and inventive minds, and productive capacity? You need a robust mechanism of engagement. It must be lightweight. It must be simple. It must be enormously flexible. It must be universally understood. Again, the “Challenge” fills that role, meeting all these requirements. In effect, the Challenge uniquely represents the enabling capability, the universal language, and the rules of engagement in neutral terms in order to empower a truly “open” access to human capital inside and outside the organization. It is magnificent in its simplicity. And in many respects, it has been hiding in plain sight for generations.

What is the inducement to this network of potential problem solvers to answer the call? For a simple idea, a small reward or inducement may be sufficient, whereas a technological innovation may require a team to spend months of time and capital to develop a winning solution, requiring substantial incentives. Internally focused challenges may reward employees with reputation, points for the company store, or lunch with the CEO. Inducements may be peer recognition or once-in-a-lifetime experiences. (InnoCentive and NASA recently offered a unique viewing of a space shuttle launch.) All these things must be assembled into a Challenge before it is exposed to the world of problem solvers. This also enables what some call the transition from Not Invented Here (NIH) to Proudly Found Elsewhere (PFE).

III A Powerful Strategy Tool

Modern corporations are expected to design their strategy processes to anticipate the future, identifying new opportunities to drive profits, investing in high return initiatives, disinvesting in low-performing businesses or programs, and ensuring the best returns on capital for shareholders. And some firms do an excellent job of methodically decomposing their broad goals into discrete strategies and tactics and may go even further to define clear measures of success. Done properly, these approaches identify gaps and opportunities for exploitation and prompt the organization to constantly rethink assumptions and model outcomes, and to manage their portfolio of possibilities—all to generate the best business outcomes for stakeholders. This approach to strategy can be highly effective but requires a process discipline and organizational transparency absent in many businesses. It also demands absolute honesty and willingness to look past the status quo, existing power structures, organizational politics, and so on. For a big organization, ignoring these pillars of corporate culture is exceedingly difficult. And therefore, incrementalism and bureaucracy are the organizational norms. The result is that in too many firms, corporate strategy is actually just a form of annual corporate planning in which resources are added or subtracted based upon growth rates and departments’ designations as profit or cost centers, or simply to provide justification for increasing or sustaining headcount or budget. A truly challenge-driven approach will shake the status quo to its foundations as its only allegiance is to outcomes and delivering performance excellence. The status quo and existing power structures have no entitlements in a Challenge Driven Enterprise.

Proper strategy requires this absolute transparency and honesty in managing the needs of the organization. By engaging head-on in this process and treating every Challenge as an opportunity to improve the business, organizations link what they do with why they are doing it. There is a top-down and bottom-up triangulation around identified Challenges that is particularly instructive. High-level strategies should be meticulously defined in the language of Challenges, which may be further decomposed as needed. Similarly, new initiatives in lower levels of the organization should be articulated as Challenges, presumably in support of high-level business strategies. By applying a discipline and a rigor, Challenges drive a richer understanding of the business and bring clarity to the prioritization process. Poorly defined Challenges are not likely to support key business strategies. By institutionalizing this approach at all levels of the organization, businesses may better tie activities to strategic goals and in the process foster the development of improved administration and problem solving across the organization. Again, use of a challenge-based approach is good management practice in any event, but should be viewed most importantly as a powerful discipline that enables more effective and open business rather than simply a cost-effective approach to solving problems.

Hallmarks of the Challenge Driven Enterprise

A great number of behaviors and competencies will describe the Challenge Driven Enterprise, but three in particular distinguish this form from most existing businesses:

• “Open” Business Model: Businesses focus their attention on their true core competencies, orchestration and strategy, to deliver against their missions. They orchestrate networks and ecosystems of customers, employees, partners, and markets. These models are highly virtualized in order to maximize innovation, agility, capital flexibility, and shareholder returns. The formation of new businesses and entrants naturally utilize these principles. Established firms must adapt to compete effectively.

• Talent Management: Think strategic virtual Human Resource Management. Businesses not only understand, but embrace key trends such as globalization, social networking, generational shifts, and project based work. Further, they recognize the importance of engagement with all their communities and the whole world to drive new ideas, product development, innovation, and even production capacity. This 21st-century evolution of HR makes it more strategic than ever before and vital to the success of the business.

• Challenge Culture: Challenges are integrated into the culture at all levels and in all functions. The needs and barriers are well-articulated and, where possible, portable. Executives, managers, and team members are trained and empowered to identify critical problems and issues and to systematically manage these Challenges through to closure for the benefit of shareholders. They can be tackled internally or externally as conditions best dictate. Challenge cultures care only that problems are solved. Who solves them and how is secondary to advancing the business mission every day. Politics, NIH, and bureaucracy are not tolerated and eliminated as inefficient and wasteful. Transparency, process integrity, and measurement are vital and hold accountable all significant projects, initiatives, and investments. Recognition, reward, and promotion systems are aligned. Orchestration skills are evident.

Early Adoption Is Well Underway

In some areas of the enterprise, some of these concepts may already be in use. To illustrate, look briefly at outsourcing and offshore software development over the last 20 years. This has been made possible by the development of well-defined rules of engagement and task definition, without which work between individuals and organizations in often different fields and geographies would not be possible. The movement, driven by the need to improve efficiency, has required software developers and managers to go well beyond the structures used in traditional systems development to create universal standards and documentation, modular tasks, and even a systematized management language.

Consider that software application requirements are routinely decomposed into modules, which are in turn assigned to individuals, teams, or individual software development houses. To ensure the right work is completed, a well-articulated design document is developed that acts as the input to the work requested. This document defines in detail the allowable technology on which to build the software, specific behaviors, any appropriate development guidelines, and even specific test cases to ensure the module meets the needs of the overall system to integrate effectively into it. The standards and business processes are so universally accepted that anyone can now engage easily with any development team, onshore or offshore development house. This standardization of business processes and documentation has been a major contributor to the development of India as a powerhouse in low-cost software development. At play here is not simply the development of outsourcing standards, but the realization that complex and mission-critical work may be packaged and deployed in a global economy when, where, and how it is best performed.

A similar story may be told in manufacturing. China, with its low-cost labor resources and now substantial industrial infrastructure, has built an enormous delivery capability in outsourced contract manufacturing. Developed over decades, there are now exceedingly well-defined standards in specifying design, acceptance, and delivery. Contracts and engagement between businesses and contract manufacturers follow standardized processes and templates. Product development and innovation functions have evolved side-by-side with legal and strategic norms in these organizations. Today, any organization that defines its needs can easily access low-cost, high-quality manufacturing capacity overseas—only possible by the clear, unambiguous articulation of needs and requirements. In fact, both software development and contract manufacturing, while specific and special purpose, are highly developed examples of sophisticated Challenges, each of which may be offered, priced, and responded to by hundreds or even thousands of “plug and play” providers.

These are special cases of a Challenge: well-defined requirements, clear acceptance and performance criteria, linkage to specific needs of the organization. And while operationally focused, they do illustrate that CDE principles are already in use in many contexts. However, organizations must take these concepts much further. The Challenge may be large or small. It can be designed to engage one, ten, or even thousands of individuals or organizations simultaneously. It is constructed with efficiency and effectiveness in mind; and it is not limited to manufacturing or software development activities. It is appropriate for a substantial percentage of work conducted by organizations in a modern business context. The Challenge Driven Enterprise may virtualize 50 percent, 80 percent, or even more of its efforts in the next 10 to 20 years. CDE represents a provocative and rationale vision of businesses that enables more open, accelerated, and profitable business than ever before possible. So whether the Challenge to envision a brand-new billion-dollar product line, to outsource manufacturing, or to develop the next-generation technology, the Challenge is fundamental and can efficiently organize business and the world around us.

Consumer products companies are leading the charge in many respects, and they were among the first to invest in and adopt open innovation. The need to stay in front of the competition and to do so consistently has required companies such as P&G to throw away the politics and “Not Invented Here” mentality of the 20th century in favor of engaging the best tools at their disposal, a technique they call Connect + Develop and which you’ll read more about in the case study at the end of this chapter.

The CDE approach, adopted pervasively, will require an evolution, if not a revolution, in business architecture. Every aspect of the organization will be engineered to maximize flexibility and access to channels capable of delivering superior results. The Challenge, representing a fundamentally better way to organize work, becomes a key enabler.

The Role of Talent Management

Generally, the talent management function in businesses is managed by the Human Resources department (HR). As the name suggests, Human Resources is not specific to the employees of the company. However, it is clear that is how it developed over time. In the highly dynamic and distributed global market for resources, HR becomes even more strategic to the success of 21st-century organizations, developing the strategies, programs, and tools necessary to deliver on the vision.

HR has always focused on identifying the need for talent in the organization and applying it against a backdrop that includes recruiting, developing, and retaining the best talent. Although the backdrop is still valid, the playing field just grew exponentially (as Figure 4.2 made dramatically clear, HR’s new talent accountability is vastly larger than it’s historically been). The Talent Management function must go well beyond hiring and firing and compliance with employment regulations, it must now empower and enable all aspects of the Challenge Driven Enterprise. With the Challenge itself playing a pivotal role in defining work, HR is now in a unique position to help transform the organization. As so many mission statements have said “it’s about the people.” Now, it’s about all the people. By working with senior management and the various functional areas of the organization to implement the vision, the enterprise transforms from a hierarchical employee-employer form to a dynamic network structure in which capabilities, processes, and talent channels enable work on a grand scale with unprecedented efficiency. Now HR must anticipate needs across the organization and identify where the talent pools may reside, inside and outside the four walls of the firm, and how best to access them reliably and cost-effectively. It is important to understand that managing a physical workforce is no longer the end goal, rather it is ensuring access to the right talent at the right time for the organization to deliver against its mission. Flexibility and agility must now define this function. And the talent panel is virtually unlimited.

HR leadership must now live up to its name. This is no less a change than the introduction of strategic sourcing and strategic supply chain management into organizations and requires business savvy, effective strategy and execution capabilities, and charismatic leadership. The HR Leader therefore plays as vital as any other member of the senior ranks of the organization. And Boards of Directors can be expected to demand talent management strategies from the CEO and HR leader that show vision, comprehend the complexity and nuance of the business, and anticipate a dramatically changing work environment, and that will scale to ensure long-term competitive advantage. Although often already part of the senior team, the Challenge Driven Enterprise for most organizations will logically precipitate elevation of HR to the C-level suite.

Leadership and Accountability Play Vital Roles

Challenge Driven Enterprises focus on outcome, assemble and disassemble business lines as needed, and execute with rigor and financial precision. They design their businesses for maximum flexibility, demand open engagement, and make exacting decisions based on the data. This challenge-driven approach will challenge leaders, processes, and culture as they exist today.

You will look at this picture of the future with hesitation and possibly contempt because we imagine leadership as having a deep and profound understanding of the needs of the business today, tomorrow, and the next day. That the fundamental tools and business practices of the past will hold true for the foreseeable future. Tragically, many organizations will misread the tsunami of competitive forces in front of them as the winds of gradual change.

Too often organizations’ leadership positions are filled with executives who measure success by the size of their organizations, budgets, and headcount. They keep score by how many factories are managed or how many engineers are under their employ. And senior executives too often convince their CEO and boards of directors that the functions are so different in their industries that normal management techniques do not apply. Innovation is seen as an output of spend. These are all outdated and outmoded notions.

Accounting for the need to indoctrinate the organization with new concepts and tools, every department in every organization should stand ready to justify its approach and expenditures; and failing to do so should result in restructuring with new leadership and work models that distribute work how and where it will be best performed.

Every CEO should be held accountable, and every CEO should hold every leader accountable. Performance excellence and the need for constant innovation are more than aspirations; they are goals that every leader and team member share. Some business will simply require new processes. But in most, the redesign will be more serious, including development of modified business architectures, upgraded skill sets and enhanced competencies, and sometimes bold new leadership. Many organizations, particularly smaller and more recent, will find this approach more natural. Large established organizations may require substantial institutional change.

The Real Challenge

The toolset described in Part I can be applied to scientific problems, business needs, and even to developing new strategies. When these principles are applied pervasively, the Challenge Driven Enterprise represents an encompassing business vision with far reaching implications. Businesses that adopt this approach will have a unique opportunity to operate more effectively than ever before and to build more flexible organizations with better, faster, and more cost-effective access to an entire world of productive capacity. And will have the flexibility to respond to market opportunities when they arise. Organizations that fail to evolve may face increasing competition by new and emerging competition not saddled by the past.

Make no mistake: This requires significant change in businesses, and the journey will be difficult. Culture becomes entrenched over time, fiefdoms are created, and the status quo sustained and codified in every process, bonus scheme, and hiring plan. Changing that culture to focus on what is important now and truly driving what is in the interest of the shareholder in the long term will not be easy. Only the CEO and the Board of Directors can drive the change needed truly become a CDE, although some successes may be the result of grass roots change. Because change is not easy for organizations, leadership will be crucial.

The remaining chapters go more deeply into the transformation necessary to drive change, put forth a playbook designed for senior leadership to support implementing the Challenge Driven Enterprise, and finally, discuss the kind of leadership requisite to successful transformational change.

Case Study: How Procter & Gamble Is Innovating Through Connect + Develop

Each year since the early 2000s, P&G asks its businesses, “What consumer needs, when addressed, will drive the growth of your brands?” This perennial exercise—managed by a large team of in-house technology entrepreneurs—is an obvious yet significant step in the ongoing innovation culture P&G lives by called Connect + Develop.

“Reduce wrinkles, improve skin texture and tone.” “Improve soil repellency and restoration of hard surfaces.” “Create softer paper products with lower lint and higher wet strength.”

These layperson descriptions are a part of what P&G dubs a top-ten-needs list, one of which is created annually for each of its businesses by the businesses themselves. All the divisions’ top-ten-needs lists together form P&G’s uber list, which informs future innovation paths.

Connect + Develop was the strategy to revitalize P&G which, in 2000, self-described its operations as a “mature innovation-based company with rapidly expanding innovation costs, flat R&D productivity, and shriveling top-line growth.”

Like so many companies in the 1980s that had moved from a centralized approach to what Bartlett and Ghoshal call the transnational model,2 P&G woke up in the 21st century to find the competitive landscape had changed dramatically, spurred by technology convergence and the new-styled global economy, in which barriers were lower—or obliterated—and competitors abound. The firm’s innovation success rates, the percentage of new products that met P&G’s financial objectives, had stagnated at about 35 percent.

A.G. Lafley, the firm’s then newly appointed CEO, assessed the business and decided only a radical new approach would bring the company back to its previous stature: Acquire 50 percent of P&G’s innovations from outside the company.

The cultural and process transformations required to make this happen were significant if not daunting. For one thing, bench scientists and researchers do not like to be told they are not innovating fast enough, and even the most confident employee might feel a twinge of insecurity about a plan to look externally for good ideas.

But P&G’s strategy wasn’t to replace the capabilities of “our 7,500 researchers and support staff, but to better leverage them,” wrote Larry Huston and Nabil Sakkab in their seminal 2006 HBR article. Better leverage, indeed, is a central theme of the entire Connect + Develop strategy.

Huston was tagged as Connect + Develop’s chief architect and driver; however, he firmly contends that the CEO of any organization must make Connect + Develop an explicit company strategy to drive the necessary cultural and business changes.

For P&G, two key factors underpinned its Connect + Develop strategy: First was the belief that finding good ideas and bringing them in-house to enhance and capitalize on internal capabilities was the right approach. It also felt it was crucial to know exactly what it was looking for—customer needs—hence the annual, systematic drafting and honing of the top-ten-needs lists.

Second is P&G’s approach around how to tap the vast outside world of innovators to meet its 50 percent target. In a radical move at the time, P&G took a wide view to developing a productive network, scouring the globe for adjacent products and innovations through its network of in-house technology entrepreneurs and its own vast network of suppliers, with its top 15 suppliers representing an estimated 50,000 researchers (in 2006).

Some of its biggest successes in recent years were established through Connect + Develop, including Mr. Clean Magic Eraser, which came from technology licensed from German chemical company BASF, and Swiffer Dusters, adapted from a Japanese competitor called Unicharm Corp. P&G negotiated the rights to sell the product outside of Japan.

Arguably, though, the most innovative aspects of Connect + Develop center on how P&G views and leverages networks beyond its own employees and suppliers using open networks. To complement its proprietary networks, P&G invested in and engages with an entire ecosystem of external partners and networks to source patents, partners, and solutions. For example, as far back as 2000, P&G was an early investor in Yet2.com, which is an online marketplace for intellectual property exchange.

Also in 2000, P&G helped create NineSigma, which crafts technical briefs (succinct problem statements) on behalf of its customers and then sends the briefs to its network of thousands of possible solution providers including individuals, companies, universities, and government and private labs for potential solutions. In 2003, the company, together with Eli Lilly and Company, established YourEncore, now operated independently, which connects a network of 5,000 retired experts with client businesses.

During the past several years, P&G has run dozens of Challenges with InnoCentive (www.innocentive.com), the marketplace pioneering challenge-driven innovation by connecting its Seeker companies who have tough but tractable problems with its global network of nearly a quarter-million expert Solvers who submit their solutions for cash awards.

The next level of P&G’s commitment to Connect + Develop is leading the way in developing the infrastructure to systematically measure the value of its open innovation practices.