10

Protection from discrimination (1) equal pay

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand how the concept of equal pay for men and women doing the same or equal work originated

- ■ Understand how the equality clause in the Equality Act 2010 works

- ■ Understand who will be a comparator

- ■ Understand the concepts of like work, work rated equivalent and work of equal value

- ■ Understand the circumstances in which pay differentials between men and women can be justified and the concept of material factor defence

- ■ Understand how equal pay claims are brought and the available remedies

- ■ Understand the significance of Article 157 TFEU

- ■ Understand the definition of pay in the Article

- ■ Understand the concept of objective justification for indirect discrimination

- ■ Critically analyse the area

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

10.1 The origins of equal pay

Equal pay law in the United Kingdom began with the Equal Pay Act 1970, although this did not gain force until 1975. Together with the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, as well as later additional enactments and amendments, the Act was aimed first at complying with the requirements of what was then Article 119 EC Treaty (now Art 157 TFEU) and second at remedying what was unjustifiable discrimination against women.

The concept of equal pay developed not from English law but as part of what is now EU law. The concept of equal pay between men and women for equal work was inserted into the original Treaty because of the potential problems that would arise from the single market with no internal barriers to trade. Member states such as France, which has had the principle of equality from the time of the revolution, may well have suffered from an inability to compete with cheap imports from countries where there was large disparity between the pay of men and women at the time the Treaties were drafted. Equality developed as a general principle of EU law, so that in cases equality is an underlying principle which the judges would consider. Since the Treaty on European Unity (TEU) it is also established in the Treaties.

A number of potential problems did originally exist from having both EU and domestic law on equal pay.

- ■ First EU law is supreme over all inconsistent national law, and by the processes of direct effect, indirect effect and state liability EU law is enforceable in national courts.

- ■ Both principles originated in the 1962 case Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen 26/62 so were established long before UK membership. As a result it is often necessary to consider both sets of law.

- ■ EU law in general is based on much broader principles than UK law. The driving force in case law in the Court of Justice is achieving the objectives of the Treaties, which are in any case broadly stated, and therefore there is much more room for interpretation. The Court of Justice inevitably looks for the broadest interpretation which will achieve the Treaty objectives for the greatest number of citizens. National law is likely to be interpreted more narrowly.

- ■ The EU method of interpretation is teleological or purposive so the ultimate question for the court is whether the objectives of the Treaties are being satisfied. This has been one of the reasons for a gradual change in emphasis from literal to purposive interpretation in English courts.

- ■ While there is no system of precedent in EU law, rulings on law in the ECJ inevitably become precedent for English courts.

- ■ Traditionally in EU law there was not the strict demarcation between pay and conditions of work that existed within the framework of the Equal Pay Act 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. In fact now both are covered by Directive 2006/54.

- ■ The definition of pay in the Treaty was traditionally much broader and has been generously interpreted by the ECJ (see 10.3.2 below).

- ■ Certainly some of the case law shows a reluctance to embrace EU principles absolutely. It is also often questioned whether, despite the legislation true equality has been achieved. Women’s pay is on average around 80 per cent of men’s, it represents a smaller share of household income, women are often referred to as a secondary workforce and their jobs are often the first under threat in times of economic hardship, and reference is still made to the so-called ‘glass ceiling’ in access to higher paid employment.

10.2 The Equality Act 2010

10.2.1 The equality clause

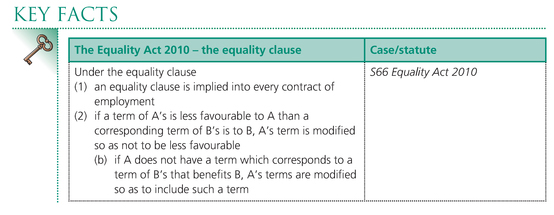

Section 66 Equality Act 2010 now contains an equality clause.

So it is implied that a woman will receive equal treatment to a man doing equal work and, if a term in a woman’s contract is less favourable than a term in the man’s contract then the contract will be modified so as make both contracts as favourable as each other. This mirrors the equality clause that was originally in section 1 Equal Pay Act 1970.

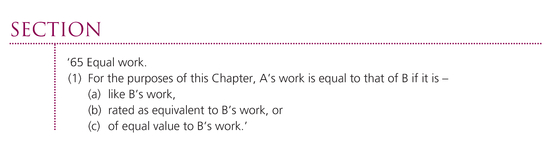

Under section 65 Equality Act 2010 the work of fellow employees is equal if it is:

- ■ like work

- ■ work rated as equivalent

- ■ work of equal value.

These are examined respectively in 10.2.3, 10.2.4 and 10.2.5 below.

The right approach for the court or tribunal is obviously to view the compared contracts term by term and to modify any term that is unfavourable. One problem that has surfaced is the 'whole contract' approach, the attitude posed by employers that the contract should not be viewed term by term but as a whole and if, even though she gets less pay than her male comparator, because a woman is getting different benefits that a man does not get that on the whole they are equally treated. This was an argument put forward in Hayward v Cammell Laird Shipbuilders Ltd (No 2) [1988] ICR 464. The argument was accepted by the tribunal which rejected the claim for equal pay. However, the House of Lords (now the Supreme Court) accepted that this would be to interfere with her rights under Article 157 TFEU (at the time Article 119 EC Treaty) (see 10.2.5 below).

One of the inevitable consequences of the approach is that it could result in a so-called 'piggy-back claim' where a man relies on a man making a claim for equal pay with a woman who has succeeded in a claim using a higher paid male comparator. This has recently been confirmed in Hartlepool Borough Council v Llewellyn [2009] IRLR 796.

Other contractual entitlements besides simply pay are also covered by the equality clause so should be considered in determining whether to grant equal pay. This can for example cover things such as concessionary travel facilities for the families of retired railway workers as in Garland v BREL 12/81; [1983] AC 751. The principle has also been applied in the case of unequal treatment in the case of contributions to pension schemes.

10.2.2 The comparator

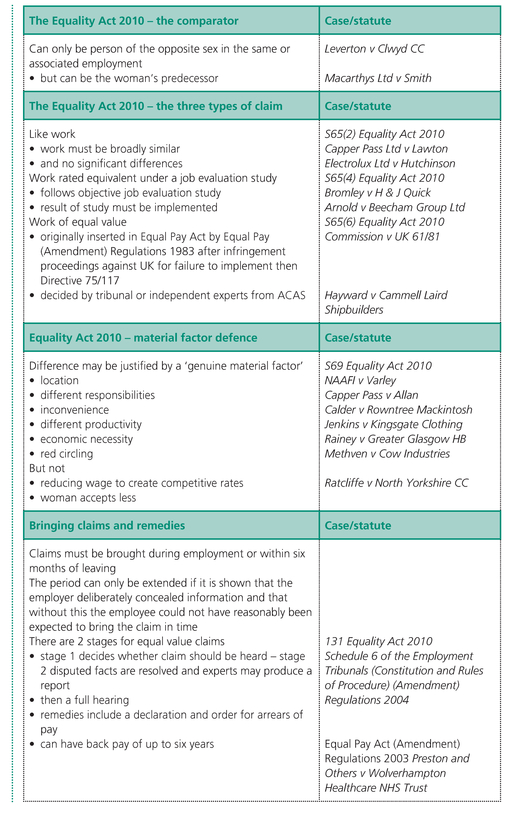

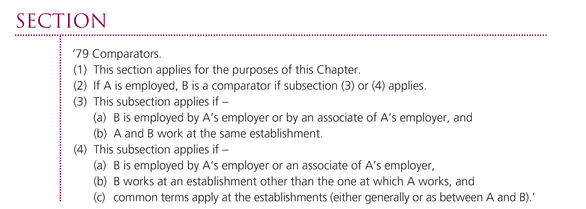

A primary requirement of bringing a claim for equal pay is that the comparator must be with a person of the opposite sex who is working in the same or associated employment. The principle is now contained in section 79 Equality Act 2010.

The Comparator should be employed at the same establishment or employed by an associated employer or at establishments which have common terms and conditions. The comparator must be typical with no personal considerations such as red circling or geographical considerations such as London weighting. The issue of common conditions was discussed in the case below.

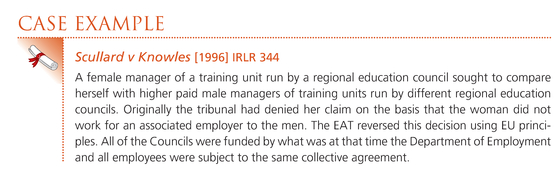

The original interpretation of associated employer from the Equal Pay Act 1970 was also much more restrictive in the case of public sector workers than would be the case under EU law.

The more recent test in establishing whether the claimant and comparator can be said to be in the same or associated employment when they work at different establishments is whether their pay generates from the same source. This was the issue on the interpretation of Article 157 TFEU (at the time Article 119 EC Treaty) in Lawrence v Regent Office Care Ltd, Commercial Catering Group and Mitie Secure Services Ltd (Case C–320/00) [2002] ECR I–7325 (see 10.3.1 below). In Armstrong v Newcastle-upon-Tyne NHS Hospital Trust [2006] IRLR 124 female health service employees working for one NHS Trust were unable to use male workers in a different NHS Trust hospital as their comparators because the Trusts were independent of each other and there was not a single source for setting pay rates. In contrast in South Ayershire Council v Morton [2002] ICR 956 a teacher working for one local authority was able to use a male teacher working for a different local authority as a comparator because their pay was set by the same national agreement.

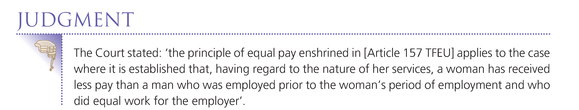

A claim is not possible against a hypothetical comparator as a result of which the original view of the UK courts was that the male comparator must be in contemporaneous employment with the female claiming equal pay. This was inevitably out of step with the broader interpretation of the ECJ.

The EAT in Diocese of Hallam Trustees v Connaughten [1996] 3 CMLR 93 applied the same principle to a female employee using the male who took over her job at much higher pay as a comparator. The disparity of pay in the case was extreme with the female being paid £11,138 per annum and her male successor receiving £20,000 per annum. Such comparisons are in any case now also indicated in section 64(2) Equality Act 2010 which identifies that a claim is not restricted to a comparator in contemporaneous employment.

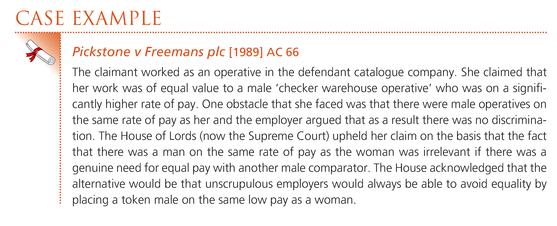

A woman is also not prevented from selecting a comparator in a claim for work of equal value simply because there is a token male who the employer has engaged in the same role as the woman on the same pay. In Pickstone v Freemans plc [1988] ICR 697 the court held that the fact that there was a man on the same rate of pay as the woman was irrelevant if there was a genuine male comparator. The House of Lords acknowledged that the alternative would be to encourage unscrupulous behaviour by employers who would then have a mechanism to always avoid equal pay (see 10.2.5 below).

10.2.3 Like work

Work is defined as like work if it is the same or broadly similar in nature and any differences are of no significance. This is identified in section 65(2) Equality Act 2010.

So the work should be broadly similar and not necessarily identical and there can be differences as long as they are not significant.

A court or a tribunal obviously needs to take a broad view of the work done and ignore insignificant differences. Where differences are significant then they might be reflected in different pay rates. There are three usual examples.

Different hours of work

A difference in working hours might justify different pay even though in other respects the work is broadly similar.

Different duties

A difference in the duties performed might obviously justify different pay since the two employees would not in that case be engaged in like work.

However, the court or tribunal must consider what actually happens in practice before deciding that there are different duties which might justify a difference in pay as can be seen in the following two cases.

Different responsibilities

Where a male employee has different, meaning greater, responsibilities than a female employee then a difference in pay might be justified.

Clearly to justify a difference in pay any alleged responsibility must be regular one not just an occasional one.

10.2.4 Work rated equivalent

An action for work rated equivalent was originally under section 1(5) Equal Pay Act 1970. This was where an employer had voluntarily engaged in a job evaluation study which had identified that the jobs of male and female comparators would be of equal value and the pay should therefore be equal and would be if it were not based on a sex-specific system of values. The action is now under Section 65(4) Equality Act 2010.

Job evaluation studies rate jobs according to the demands made upon the individual employee in various set factors including skill, effort, responsibility, decision making. Job evaluation studies are gender neutral where a sex specific system sets different values for men and women.

Where a genuine scheme has occurred then its findings should be implemented.

Different types of study have been developed as was pointed out by the EAT in Eaton Ltd v Nuttall [1977] IRLR 71 such as job ranking, paired comparisons, job classification, points assessment and factor comparison.

Any genuine study then must be objectively applied and analytical with the separate factors in each job compared, so 'whole job' comparisons are not really adequate for this purpose.

10.2.5 Work of equal value

The definition of a claim for equal pay for work of equal value is now contained in section 65(6) Equality Act 2010.

A claim for equal pay for work of equal value was actually inserted into the Equal Pay Act as section 2A(1)(a) by Regulation 2 of the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations 1983. This extra head of claim was added because it was lacking in the original Equal Pay Act and the UK then failed to fully implement the requirements of Article 119 EC treaty (now Article 157 TFEU) as expanded in the then Equal Pay Directive 75/117 (now part of the Recast Directive 2006/54). This subsequently led to infringement proceedings in the European Court of Justice in Commission v UK 61/81. In the case the argument made by the UK that the concept of 'equal value' was too abstract to stand application was rejected by the court.

An action for equal pay for work of equal value, as section 65(6) Equality Act 2010 identifies, may be brought when there is no male comparator doing like work or there is no work rated as equivalent in a genuine job evaluation study.

The process is now governed by section 131 Equality Act 2010 and regulations contained in Schedule 6 of the Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) (Amendment) Regulations 2004 which also set maximum timescales of twenty-five weeks if no independent expert is used and thirty-seven weeks if independent experts are used. The previous procedure was long-winded and full of potential delays with the average time taken to complete claims being two-and-a-half years, a real disincentive to claiming.

Claims can obviously be quite complex and take time to resolve because a number of comparators may be used.

It is possible for a woman to pursue a claim for equal pay for work of equal value despite there being other men on the same wage provided that there is a male comparator on a higher wage.

10.2.6 Justifications for unequal pay

Traditionally an employer had a defence to an equal pay claim where he could show that the difference in pay was due to a genuine material factor where the difference in pay was not based on the person’s sex. This defence is now contained in section 69 Equality Act 2010.

There have been a variety of contexts in which employers have argued that a genuine material factor justifies differences in pay.

Geographical location

Geographical location may be a justification for differences in pay. This operates where national employers have employees at different locations around the country and living costs can vary. A classic example was the challenge to what is known as London weighting in NAAFI v Varley [1976] The Times 25 October. Men and women might be doing the same work but in different parts of the country where living costs are much higher and therefore employers have to offer better rates of pay to attract staff.

Different responsibilities

We have seen in 10.2.3 above that different duties and responsibilities may mean that the work is not in fact taken as being broadly similar.

Different productivity

This has particularly risen in relation to different treatment of part-time employees by contrast to their full-time counterparts and has been considered also by the ECJ.

Economic necessity (market forces)

The need to attract staff with particular skills or where skills are scarce can also be a factor that has been accepted as justifying paying higher rates than might be the case with the existing workforce.

However, there are limits to how far an argument of market forces will be accepted when the reality is that the pay differential is in fact discriminatory.

Inconvenience

It may also be possible to argue that the difference in pay is justified because the nature of the man’s role involves unsocial elements and inconvenience not present in the woman’s.

The decision is possibly at odds with the principle that a woman employed in a female dominated occupation can still bring a claim using a comparator from a male dominated occupation.

Red circling

This involves salaries that are protected for some reason. This will usually occur where an employee has had to accept redeployment into a lower paid job or because the employee is unable to continue in the same role, for instance because of health issues. The employer wishes to retain the employee and keeps him on the same pay even though he is working in a role on a lesser pay grade.

It may be possible to justify this and use it as a defence if the decision to 'red circle' the previous wage was not made on a discriminatory basis.

However, 'red circling' is not a guarantee of a defence of genuine material factor and an employer should not think that there is an automatic right to carry on such a practice since it is also potentially offensive to the remainder of the workforce. A temporary situation is more likely to succeed than a permanent situation. In any case the significant question is why the pay has been 'red circled' and whether or not this is discriminatory. If it is then the defence is not available.

Incremental pay grading

Many forms of employment use incremental pay scales. Employees get an incremental increase in salary for each year of service until they reach the top of the pay scale. This may justify differences in pay since it is recognition of the extra experience that the employee has and therefore could be linked to productivity or capability.

However, the practice could also be discriminatory to women in the sense that since because of maternity and the child care responsibilities it is possible at any given time that there are a greater number of male employees with advanced service. The ECJ has considered this in detail and determined that while the practice may be justified it must be objectively justified.

10.2.7 Making equal pay claims

A claim for equal pay must be brought to the tribunal during the course of employment or within six months of leaving. Application is made on the same forms as for other claims. There is no right to extend this limit. However, the period may be extended if it is shown that the employer deliberately concealed information and that without this the employee could not have reasonably been expected to bring the claim in time.

The procedure for making a claim for equal pay for work of equal value is now governed by section 131 Equality Act 2010 and regulations contained in Schedule 6 of the Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) (Amendment) Regulations 2004 which set maximum timescales of twenty-five weeks if no independent expert is used and thirty-seven weeks if independent experts are used.

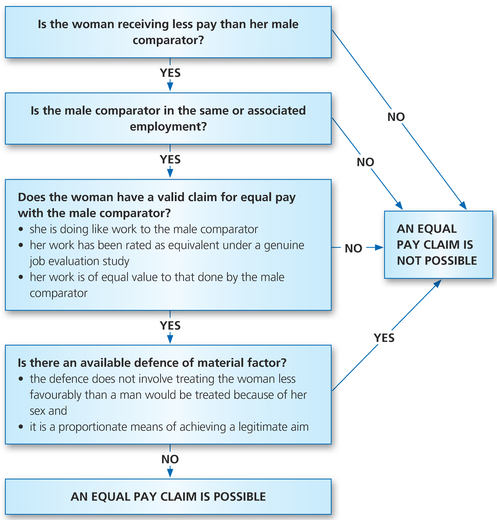

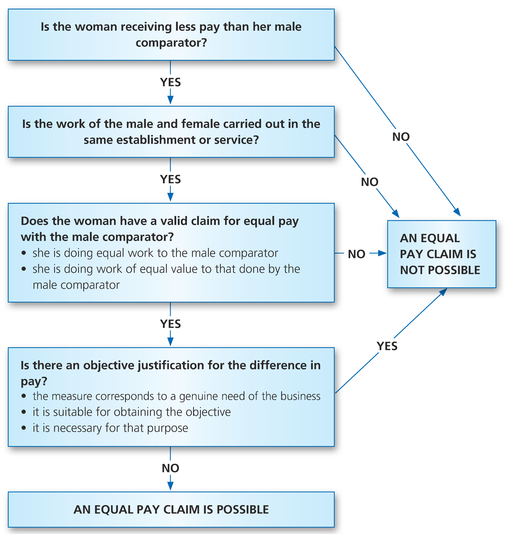

Figure 10.1 Diagram illustrating the elements of an equal pay claim under the Equality Act 2010

The procedure has two stages. Stage 1 will apply to all claims and the tribunal determines whether the claim should proceed and also whether to hear it itself or whether to appoint independent experts from ACAS. In Stage 2 any disputed facts are resolved and experts, if used will prepare a report. After this there is a full hearing at which the issue whether to award equal pay is decided.

10.2.8 Remedies

There are essentially two aspects to any award for equal pay:

- ■ first if the claim has succeeded then the tribunal will issue a declaration to that effect and stating that the employee is entitled to equal pay and ordering the employer to increase the pay;

- ■ second the tribunal will make an order for arrears of pay. This could include any other benefits or bonuses or other perks.

Thus the contractual obligations of the employer and rights of the employee are in effect changed.

The arrears can be backdated for a period of up to six years from the date when the claim was brought. This follows the change made by the Equal Pay Act (Amendment) Regulations 2003 to the old maximum of two years. This change arose because of the finding in the ECJ in Preston and Others v Wolverhampton Healthcare NHS Trust (C-78/98) [2000] ECR I-3201 that the then restriction was in breach of EU law.

10.3 Article 157 Tfeu

10.3.1 The basic protection

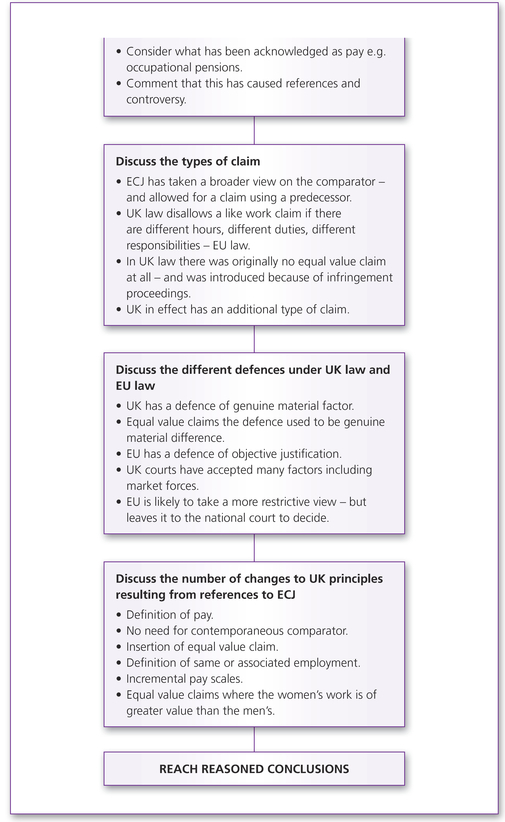

Originally Article 119 of the EC Treaty identified that men and women should receive equal pay for equal work. Following renumbering under the Amsterdam Treaty this became Article 141 EC Treaty. Following the replacement of the EC Treaty with the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) the principle is now contained in Article 157 TFEU.

The principle is a simply stated one and was originally under Article 119 EC Treaty mainly a part of the economic agenda of securing a single market (at that time referred to as the common market). It was established at a relatively early stage that the Article was directly effective (see Chapter 2.2.3) and therefore is enforceable by a citizen of the EU in a national court of a Member State.

One sad aside to the case followed representations made to the court by both the UK and Ireland who feared the effect the ruling could have. Following these representations the Article was held to be only prospectively, rather than retrospectively, directly effective as should have been the case. As a result many women in those Member States lost out on potential and justifiable claims which they otherwise might have made.

One important limitation on the scope of Article 157 was also identified by the ECJ in the case, that Article 157 can only be used in respect of 'equal work which is carried out in the same establishment or service’. In consequence a woman cannot claim equal pay with a man employed by a different employer even if they are doing exactly the same work. This was later confirmed and explained by the court.

The same principle was also later applied in a situation involving a comparison between permanent employees and agency workers.

10.3.2 The definition of pay

The EC Treaty also defined pay quite broadly. The definition is now in Article 157(2) TFEU.

The definition of pay in the Article is not limited to 'wages' or 'salary'. It can include any form of remuneration which does not have to be in the form of money. The definition has also been very broadly construed by the ECJ in case law. Examples of what has been accepted as pay for the purposes of Article 157 have included the following:

- ■ perks e.g. concessionary rail fares for retired railway workers, Garland v BREL 12/81 – the ECJ held that it was irrelevant that the benefits were not laid down in the employment contract;

- ■ supplementary payments into an occupational pension scheme, Worringham & Humphries v Lloyds Bank Ltd 69/80;

- ■ sick pay, Rinner-Kuhn v FWW Spezial Gebaudereinigung GmbH & Co. KG 171/88;

- ■ paid leave for training, Arbeiterwohlifahrt der Stadt Berlin v Botel – the ECJ stated that remuneration could amount to 'pay' 'irrespective of whether the worker receives it under a contract of employment, by virtue of legislative provisions or on a voluntary basis';

- ■ contractual non-contributory occupational pension schemes, supplementing state schemes, denied to part-timers, Bilka-Kaufhaus v Weber von Hartz 170/84;

- ■ unequal retirement ages, Marshall v Southampton & South West Hampshire AHA (Teaching) (No 1) 152/84;

- ■ redundancy payments, R v Secretary of State for Employment ex parte Equal Opportunities Commission [1995] 1 AC 1 (HL);

- ■ 'contracted out’ pension schemes which depend for operation on different retirement ages, Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange Assurance Group 262/88 – the case is also important in identifying that Art 157 is infringed if pension rights are deferred in a person made compulsorily redundant to retirement age (if different to person of opposite sex) – so applies Marshall logic to contracted out schemes – but had prospective direct effect like Defrenne;

- ■ in Royal Copenhagen case (C–400/93) [1995] ECR I–1275, the ECJ was asked whether pay on a 'piece-work' basis – where the level of pay is wholly or partially dependent on the individual employee’s output – was covered by Article 157 and the court held that it was;

- ■ severance payments, Kowalska [1990] ECR I–2591 – these payments are designed to help employees who became unemployed involuntarily, for example, following retirement or disability, to adjust to their new situation;

- ■ compensation for unfair dismissal, Seymour-Smith & Perez [1999] ECR I–623 – the ECJ described it as 'a form of deferred pay to which the worker is entitled by reason of his employment but which is paid to him on termination of the employment relationship with a view to enabling him to adjust to the new circumstances arising from such termination';

- ■ bonuses, Krüger (Case C–281/97) [1999] ECR I–5127, involved annual Christmas bonus;

- ■ a monthly salary supplement, awarded by an employer on an ad hoc basis to reflect the quality of individual’s work, Brunnhofer (Case C–381/99) [2001] ECR I–4961;

- ■ maternity pay, Gillespie v Northern Health and Social Services Board (Case C–342/93) [1996] ECR I–475;

- ■ occupational pensions – this area has possibly provided some of the more contentious application of the definition in Article 157(2).

The occupational pension scheme in the Bilka Kaufhaus case was one that supplemented the state pension scheme. In a later judgment the ECJ identified that the definition under Article 157(2) also covered so-called 'contracted out' schemes, ones designed in effect to replace the state scheme.

The ruling proved quite controversial and, because of the potential effects on contracted out schemes the court decided to apply the ruling prospectively and not retrospectively. The case also led to several preliminary rulings, mainly from the UK and the Netherlands.

10.3.3 Indirect discrimination and objective justification

Pay was originally covered by the Equal Pay Directive 75/117. This is now in the Recast Directive 2006/54.

The Court of Justice has identified in Macarthys Ltd v Smith (Case 129/79) [1980] ECR 1275,that 'equal work' does not necessarily have to mean identical work but work with a high degree of similarity.

In the case of work of equal value this is a question of fact for the national court to determine whether work is of equal value. Although determining exactly how different jobs should be assessed has been problematic. Article 4 of Directive 2006/54 (the recast Directive) gives some guidance. It states that 'where a job classification system is used for determining pay, it must be based on the same criteria for both men and women and so drawn up as to exclude any discrimination on grounds of sex'.

The ECJ has also developed the test for how to measure what is objective justification for differences in pay. In Bilka Kaufhaus GmbH v Weber von Hartz [1987] ICR 110 the ECJ held that national courts should decide whether there is a real need to apply different rules for part-timers, but that there must be objective justification. It identified the criteria for establishing objective justification:

- ■ the measure must correspond to a genuine need of the business;

- ■ it must be suitable for obtaining the objective;

- ■ it must be necessary for that purpose.

It is also important to note that the court will not accept that the mere fact that a system for job classification for determining salary scales is apparently neutral guarantees that it is not discriminatory.

One significant failing in equal pay legislation is that, while it may lead to an aggrieved party gaining equal pay this does not necessarily mean that she gains the pay that she deserves in the light of the evidence.

Figure 10.2 Diagram illustrating the elements of equal pay under EU law

The anomaly here is that the women received equal pay with the men when they should in fact and in fairness have been receiving higher pay.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 5.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 7.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 5.3.

Storey, Tony and Turner, Chris, Unlocking EU Law 3rd edition. Hodder Education, 2011, Chapter 18.