2

The effects of EU membership on UK employment law

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the background to UK membership of the EU

- ■ Understand what is meant by the supranational order

- ■ Understand the concepts of supremacy, direct effect, indirect effect and state liability and how they operate

- ■ Understand how EU labour has developed and how it impacts on UK employment law

- ■ Critically analyse the area

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

2.1 UK membership of the European Union

2.1.1 Introduction

Many areas of English Law have now developed beyond recognition as a result of the UK joining what originally was the European Economic Community (EEC), later the European Community (EC), which following the Treaty on European Union (TEU) became a central pillar of the European Union (EU), and now following the Treaty of Lisbon is the European Union.

The UK was in fact invited to take part in the framing of the original three Treaties with a view to becoming a member of an economic community that in effect began with six nations, France, Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, in 1957. However, for various reasons, both economic and political, the UK declined to become involved either in the drafting of the Treaties or founding membership. Later abortive attempts to join were made but it was not until sixteen years later that the UK eventually became a Member State on 1 January 1973. Membership of the EU has had a significant impact on the UK in most economic areas and this is certainly the case with the law governing employment, particularly those providing employment protections.

2.1.2 The basis of UK membership

The UK government having signed the treaty of accession was also required then to pass an Act of Parliament to incorporate membership and the Treaties into English law. This is because the UK has a dualist constitution: this means that international treaties do not automatically become part of the constitution and gain force merely on signing, they need to be incorporated. Other Member States have dualist constitutions, including Germany, Italy and Belgium. In monist constitutions, on the other hand, the treaty is automatically incorporated into the national legal system at the point of ratification. Member States with monist constitutions include France and the Netherlands.

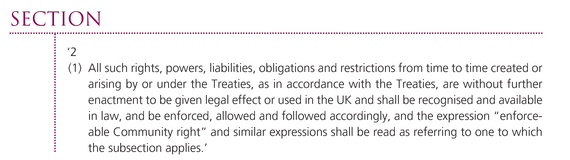

Other than the power to implement EU legislation through delegated legislation granted in section 2(2) there are two other critical sections. Section 2(2) states:

This section was of course vital, not only for the purpose of implementing EU legislation as required under the Treaties but for being able to repeal inconsistent national law without the constant need for Act of Parliament.

The section actually incorporating the Treaties, and in consequence EU (at that time EC) law, is section 2(1). This section states:

This is a quite straightforward enactment and is a simple statement of intent. The UK by the enactment automatically incorporated all existing EU law including the Treaties and all existing secondary legislation. Also all future EU legislative provisions would become law and be recognised as enforceable.

In the case of future EU legislative measures such as Regulations this would be automatic because they are described in Article 288 TFEU as 'directly applicable', meaning that they automatically become law in Member States with no need for further enactment, except possibly to repeal inconsistent domestic legislation. In the case of directives these are defined in Article 288 as 'binding as to the result to be achieved'. Member States are obliged to implement by a set date but can do so in the manner they choose. In the case of directives then section 2(1) identifies that this will happen.

One other clear consequence of section 2(1) is that the case law of the Court of Justice becomes a part of English law and because of the doctrine of precedent will exist as precedent for English courts to follow.

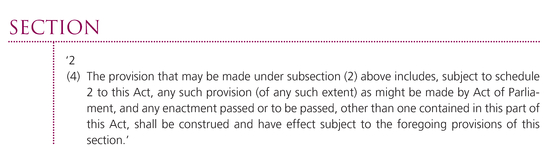

Section 2(1) is also supplemented and reinforced by section 2(4), which states:

Following the enactment of the Act the existence of previous English law that might conflict with the broad aims of the Treaties presented no real problem; it was in effect automatically repealed by the Act. The major problem concerns either the possibility of English law made after the passing of the Act which is inconsistent with provisions of EU law, or a failure by the UK government to implement or give effect to EU law as required. The problem seems to hinge on the extent to which the above sections are in fact entrenched or whether they are merely aids to construction.

2.2 The supranational legal order of the EU

One of the major problems facing a union of nations subjecting themselves to a common legal order is that there is likely to be a wide variance in how the Treaties are then interpreted and applied in the individual Member States. In fact the whole history of the EU (and the former EC) demonstrates a constant tension between the commitment of the EU institutions, particularly the Court of Justice, striving to achieve the objectives of the Treaties and national self-interest acting as a break on progress.

In consequence it was envisaged even before the Treaties were drafted that for the legal order to have any effect the institutions must be 'supranational' in character and in effect. Supranational simply means in areas involving Treaty obligations or those created under subsidiary legislation, the EU institutions and obligations are superior to national law and institutions. In pursuing supranationalism and seeking to give full effect to the EU legal order and the attainment of Treaty objectives the Court of Justice has undeniably been the most significant institution both in administering and defining EU law. In many ways it has created the principle of 'supranationalism' through developing the principles of supremacy, direct effect, indirect effect and state liability.

2.2.1 EU legal instruments

The Treaties, now principally the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and the Treaty on European Union (TEU) are obviously the most significant source of EU law and they are the primary source of law. Apart from anything else they include the broad objectives of the EU as well as outlining a variety of substantive rights. Inevitably, however, legislation is needed to provide greater detail.

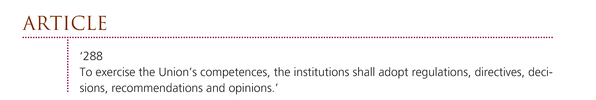

EU subsidiary legislation is given force in Article 288 of the TFEU (originally Article 189 EC Treaty). This identifies that:

Besides identifying the power of the institutions to introduce legislation, Article 288 also goes on to define the different forms of secondary legislation. There are in fact five but two are of particular significance; regulations and directives.

Regulations

Regulations are relatively straightforward legislative instruments often used for development of broad principles. Looking at the terminology used in the Article:

- ■ 'General application' means that a regulation applies generally to the whole of the EU, to all Member States.

- ■ 'Binding in its entirety' is also straightforward; it means that Member States have to give effect to the whole regulation with no exception.

- ■ 'Directly applicable' is probably has the least obvious meaning but is hugely significant in terms of supranationalism meaning that a regulation automatically becomes law in each Member State on the date specified without any need for implementation of any kind – the consequence being that it is superior law to inconsistent national law, if not before, certainly after the creation of the doctrine of supremacy of EU law (see Chapter 2.2.2).

Regulations are also obviously capable of creating rights and obligations which are then directly enforceable in the national courts through the principle of direct effect (see Chapter 2.2.3).

Directives

Directives are a more complex and potentially more problematic legislative measure. Looking at the terminology in Article 288 there are two significant aspects to directives:

- ■ 'Binding as to the object to be achieved' means that, while directives are binding on Member States, unlike regulations which are directly applicable and demand absolute uniformity, they are used instead for harmonisation of law, to ensure that Member States adapt their own laws for the application of common standards in order to achieve the objectives laid out in the directive.

- ■ 'Shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods' means again that, unlike with regulations that automatically become law in Member States, directives give an element of discretion to the Member States and allow them to choose the most appropriate method of implementation to achieve the objectives set out in the directive.

A third key aspect of directives is that Member States are given an implementation period so that the directive must be implemented into domestic law within a set deadline.

Because directives are harmonising measures they are mainly used in areas where the diversity of national laws could prevent the effective functioning of the single market. There are many examples in the field of employment which can be found in the following chapters including:

- ■ the Pregnant Workers Directive 92/85 in Chapter 8;

- ■ the Agency Workers Directive 2008/104 in Chapter 4;

- ■ the Equal Pay Directive 75/117, Equal Treatment Directive 76/207 and the Recast Directive 2006/54 that replaced them in Chapters 10 and 11;

- ■ the Working Time Directive 93/104, the Young Workers Directive 94/33 and the Working Time Directive 2003/88 in Chapter 16;

- ■ the Acquired Rights Directive 77/187 in Chapter 18.

There are references to EU directives in most chapters indicating the influence of EU membership on UK employment law.

One problem associated with directives is whether they are enforceable if Member States fail to implement or fail to implement properly. An example of the former can be found in Chapter 16 with the then UK Conservative government failing to implement at all the Working Time Directive 93/104. This was only implemented in the UK after a change of government in 1997. Examples of the second can be found in Chapter 10 where the UK government was the subject of infringement proceedings in the ECJ for its failure to fully implement Directive 75/117, the Equal Pay Directive by providing an action for equal pay for work of equal value. The problems caused by the definition of directives under Article 288 led to the ECJ developing the concepts of direct effect, indirect effect and state liability in order to ensure that EU citizens were able to benefit from the rights given in directives (see Chapter 2.2.3) and the seminal case of Marshall v Southampton and South West Hampshire AHA (Teaching) (No 1) 152/84 [1986] QB 401 provides another classic example of an incompletely or improperly implemented directive, and also of the determination of the ECJ to ensure that the enforceability of rights emanating from it.

2.2.2 Supremacy

Supremacy is probably the most entrenched and yet surprisingly the least contested of EU principles. This of course is fairly surprising in the UK considering the almost insti-tutionalised scepticism towards the EU and the fact that membership is still a hotly debated issue, even in political circles, nearly forty years after the UK joined and almost as many since a Yes vote in a referendum on membership.

The Treaties in fact make no reference to supremacy of EU law over national law. Article 4(3) TEU does state what has often been referred to as the oath of allegiance (formerly in Article 10 EC Treaty).

It is obvious that it is essential that EU law should be uniformly applied throughout all Member States. Without supremacy the institutions would not be supranational and would have no effective power and the full economic integration necessary to achieve the single market would have been impossible if Member States were able to ignore or even deliberately defy the supranational powers of the institutions of the EU. The single market depends upon harmonisation of laws between Member States, which in turn depends on uniform application of EU law within the Member States. In fact the whole structure of the EU was based on the idea of supranationalism.

The ECJ has been proactive in developing a doctrine of supremacy of EU law without which the institutions would have been deprived of any supranational character and effect and uniformity would inevitably have been sacrificed to national self-interest.

In consequence there are two real justifications for the ECJ having developed the doctrine:

- ■ First it prevents any possibility of a questioning of the validity of EU law within the Member States themselves.

- ■ Second it fulfils what has sometimes been referred to as the 'doctrine of pre-emption'. It achieves this in two principal ways:

- first supremacy of EU law over inconsistent national law means that the courts in the Member States are prevented from producing alternative interpretations of EU law which may then result in lack of harmony and a disruption to the effective running of the single market;

- second the doctrine has the other critical consequence that the legislative bodies of the individual Member States are prevented from enacting legislation that would conflict with EU law.

The first statement suggesting the supremacy of EU law over national law came in Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen [1963] 26/62 ECR 1, [1963] CMLR 105 (the case principally concerns the issue of direct effect and is therefore more fully discussed in 2.2.3 below). A Dutch citizen suffered financial loss as a result of a breach of EU (at the time EC) law. In a reference to the ECJ the question was whether or not the treaty created rights on behalf of individuals that were then enforceable in national courts.

In the reasoned opinion the Advocate General declared that this was not the case and that the appropriate means of resolution in such circumstances was in an action against the Member State under Article 258 TFEU (at the time Article 169 EC treaty). The Judges in the ECJ disagreed.

The major explanation of the doctrine and its implications was provided by the court only two years later.

This was the first clear definition and explanation of the consequences of the doctrine of supremacy. It was followed by International Handelsgesellschaft GmbH v EVGF 11/70 [1970] ECR 1125, [1972] CMLR 255 which extended the principle supremacy to include national constitutional principles over which EU law would still be supreme. In Sim-menthal SpA v Amministrazione delle Finanze dello Stato 70/77 [1978] ECR 1453, [1978] 3 CMLR 670 the ECJ also identified that supremacy applies whether the national rule comes before or after the EC (now EU) rule. In Commission v France (The Merchant Sailor's case) 167/63 the court also identified that supremacy applies not just to directly conflicting national law but to any contradictory law which encroaches on an area of Community (now the EU) competence.

There are some obvious consequences of the doctrine:

- ■ Member States have given up certain of their sovereign powers to make law –in fact sovereignty is pooled rather than lost.

- ■ The Member States as well as their citizens are bound by EU law (and may gain rights from EU law – see 2.2.3 below).

- ■ The legislature of Member States cannot unilaterally introduce law that conflicts with their EU obligations.

The clearest example of this last point and also the most dramatic statement of supremacy interestingly involves legislation of the UK Parliament.

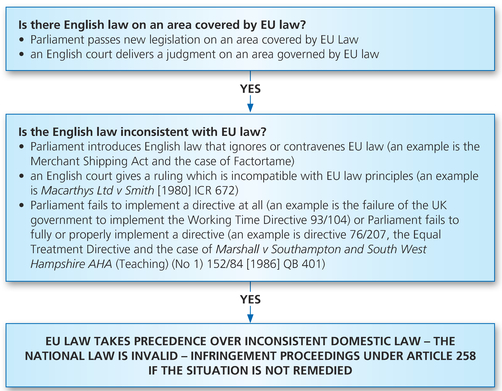

Figure 2.1 Flow chart illustrating how supremacy of EU law works

2.2.3 Direct effect, indirect effect and state liability

The basic requirements for direct effect

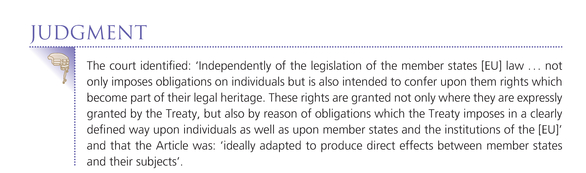

As with supremacy (see 2.2.2 above) direct effect was the creation of the ECJ. It created both concepts in the same case. Direct effect simply means the ability of a citizen of the EU to enforce principles of EU law in a national court. Both concepts are essential if the objectives of the treaties are to be achieved and the principle of supranationalism on which the single market is based. In this case the citizen would have had no protection if he had been unable to rely on EU law in the case.

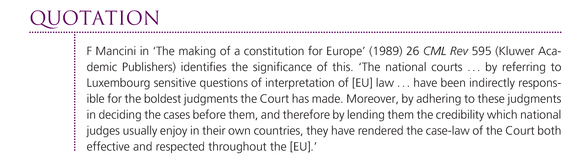

As indicated by the Advocate General the original method for ensuring that EU law was enforced in Member States was by infringement proceedings under Article 258. The ECJ established the process of direct effect because it was a much more effective means of ensuring that citizens of Member States could enforce the rights given to them by the Treaties. The uncompromising nature of the court led to it also developing the principles of indirect effect and state liability to ensure that citizens benefit from the rights granted them in the Treaties. However, this has been dependent on reference procedure and the national courts.

The court also identified the criteria for direct effect.

- ■ The provision must be sufficiently clear and precisely stated – the ECJ in Defrenne v SABENA 43/75 was satisfied that the principle that 'men and women shall receive equal pay for equal work' was sufficiently precise to create direct effect even though the exact meaning of 'equal pay and equal work' would inevitably require further definition by the courts.

- ■ The provision must be unconditional or 'non- dependent' – in the sense that it should not depend on the intervention of another body or require further legislative action either by the [EU] institutions or Member States.

Besides these for individuals to be able to enforce a provision of EU law there must be an identifiable right granted by the Treaty or subsidiary legislation.

Direct effect in application

In Van Gend en Loos the action was against the state. The next significant issue was whether a citizen could rely on the principle of direct effect to enforce a provision against another citizen as the case had confirmed they could against the state. In Defrenne v SABENA involving a claim for equal pay made against an employer under what is now Article 157 TFEU (see Chapter 10), the ECJ rejected the argument that direct effect was a means only of enforcing substantive EU laws against the Member States. The court clarified that there were in fact two types of direct effect, vertical direct effect (against the state) and horizontal direct effect (against other citizens and private bodies. This was necessary because otherwise citizens would be denied effective remedies where they were granted rights under EU law.

The court has also developed the principle of direct effect so that it applies generally to most types of EU law, both primary and secondary. It has generally followed its own criteria in Van Gend en Loos. However, the test from the case was originally strictly applied but the court has also gradually taken a more relaxed approach to ensure that citizens can take advantage of the rights given to them in the Treaties.

In the case of Treaty Articles there is no problem in conforming to the criteria in Van Gend en Loos since Treaty Articles automatically become part of national law by signing the Treaty or also by ratifying in a duellist constitution such as the UK which did so through Act of Parliament. Neither are there any problems in enforcing Regulations since, as identified in Article 288, they are directly applicable, meaning they automatically become law in Member States without need for implementation. This was established in Leonesio v Ministero dell’Agricoltora & delle Foreste 93/71 (The widow Leonesio).

Direct effect and directives

In the case of directives there was a potential problem because of how they are defined in Article 288. They create obligations on Member States to pass national laws within a set time to achieve the objectives in the directive but this means that they fail one part of the test in Van Gend en Loos. They are conditional. They are not non-dependent. They are entirely dependent on implementation by the Member States.

The ECJ identified this problem at an early stage in Van Duyn v Home Office 41/74 which involved enforcement of what was then Directive 64/221 (now Directive 2004/38) and derogations against the free movement of workers under what was then Article 48 EC Treaty (now Article 45TFEU). The ECJ considered the problem of the direct effect of directives and reached an important conclusion.

The judges foresaw that directives could be made ineffective without allowing direct effect and was prepared to overlook the potential limitation involved in their definition in Article 288.

On this basis, while the court gave little other reasoning it identified that a directive can indeed be enforced by the means of direct effect provided that the remaining criteria from Van Gend en Loos are met. During the implementation period the rights produced by directives are not enforceable because Member States have a time limit within which to implement. As a result, for directives the court added an extra criterion to the Van Gend en Loos test in Pubblico Ministero v Ratti 148/78 that direct effect of a directive is not in question until such time as the implementation period has expired.

The Court of Justice can only deal with problems as they arise in references to it. The next limitation to be identified was that directives have only vertical direct effect. They can never be horizontally directly effective and so can only be relied upon and enforced against the state.

This left an anomalous and unjust situation that showed up in Duke v GEC Reliance [1988] 2 WLR 359 which involved the same issue as Marshall, but the employer was a private company. The House of Lords held that it was not bound to apply Directive 76/207 because the directive could not be effective horizontally. Even though the UK was at fault for failing to fully implement the directive the availability of a remedy then was entirely dependent on the identity of the employer.

The ECJ was subsequently able to extend the scope of vertical direct effect to include bodies that could be described as an 'emanation of the state' (or 'arm of the state'). The court devised a test in Foster v British Gas plc C- 188/89 another case involving the issue in Marshall:

- ■ is the body one that provides a public service, and

- ■ is the body under the control of the state, and

- ■ is the body able to exercise special powers that would not be available to a private body?

The ECJ made progress in making the rights arising from directives enforceable but the absence of horizontal effect meant that there were still problems.

Indirect effect

In yet another case involving the Equal Treatment Directive and its improper or incomplete implementation in Member States the ECJ was able to develop a further process to avoid the problem that unimplemented directives cannot be enforced through horizontal direct effect. This was the process of indirect effect which was explained by the court in two cases referred to it by the German Labour Court.

Indirect effect is a process of sympathetic interpretation by a national court seeking to give effect to the objectives in a directive and is a way of avoiding the problem of there being no horizontal direct effect of directives. The judgment was not clear on which national law the process of indirect effect could actually apply to. This was resolved in Marleasing SA v La Commercial Internacional de Alimentacion C- 106/89.

However, there are limitations to the process the most significant being that the process is entirely dependent on the willingness of the national courts to use it. As has been seen in Duke the national courts are not always so willing so that there is the possibility of lack of uniformity throughout the EU.

The other limitation is that it would be unlikely that a national court could give indirect effect to a directive which had not been implemented at all. This would first mean that the court was legislating and second would be unfair on a citizen who was only complying with national law.

State liability

Despite the efforts of the ECJ to ensure that citizens were able to enforce the provisions of improperly implemented directives first through vertical direct effect against the state and emanations of the state and second by introducing the process of indirect effect there were still situations where a party could be without a remedy because of the failure of a Member State to implement at all or fully implement a directive. As a result, when it got the opportunity the ECJ developed a third way of ensuring that citizens did not lose rights given in directives. This is the process of state liability. If a citizen lacks a remedy and suffers loss or damage because of the failure of a Member State to implement EU law then that Member State should be made liable for the damage suffered.

The court set three conditions for state liability to apply:

- ■ The directive must confer rights on individuals.

- ■ The contents of those rights must be identifiable in the wording of the measure.

- ■ There must be a causal link between the damage suffered and the failure to implement the directive.

In Brasserie du Pecheur SA v Federal Republic of Germany; R v Secretary of State for Transport, ex parte Factortame Ltd C- 46 and C- 48/93 the court then modified the conditions from Francovich, ignoring the original second condition and replacing it with a new one:

- ■ The rule of Community law infringed must be intended to confer rights on individuals.

- ■ The breach must be sufficiently serious to justify imposing state liability.

- ■ There must be a direct causal link between the breach of the obligation imposed on the state and the damage actually suffered by the applicant.

The definition of state has widened to include acts and omissions of any organ of the state and the scope of liability has been extended beyond directives to include any breach of EU law, regardless of whether or not it has direct effect.

One issue is what will amount to a sufficiently serious breach of EU law. Dillenkofer and others v Federal Republic of Germany C- 178, 179, 188, 189 and 190/94 identified that there are situations where the seriousness of the breach is obvious and the imposition of state liability is then almost a form of strict liability. An example is where there is a failure to implement a directive at all. R v Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, ex parte Hedley Lomas (Ireland) Ltd C- 5/94 identifies that in all other cases the seriousness of the breach must be established.

State liability conflicts with national rules on non-implementation but the need to show direct effect is removed as is the strained construction of national law through indirect effect. Instead it focuses on the duty of the Member State to implement EU law while in effect attaching rigorous sanctions for failure to implement. As a result it has the effect of removing any advantage that Member States might gain from non-implementation. State liability is the most far reaching principle of all and it has several implications:

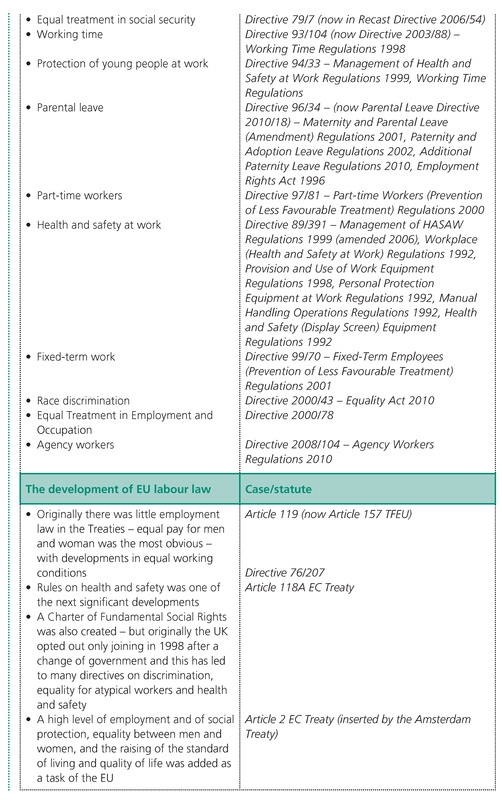

2.3 The importance of EU membership to UK employment law

2.3.1 UK implementation of EU law

As we have seen in 2.1.2 above initially the most significant implementation of EU law was the European Communities Act 1972. This incorporated into English law all existing EU law and identified that all future law would also become English law. At the time there was actually a limited amount of law in the Treaty specifically on employment. However, since that time an enormous amount of employment law has been affected by

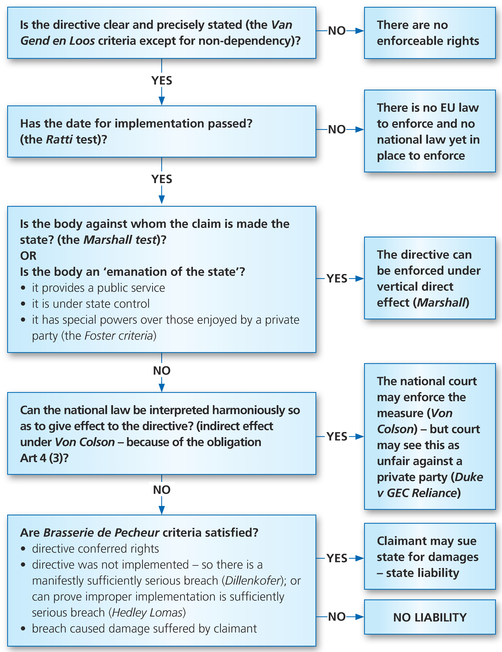

Figure 2.2 Diagram illustrating the possible means of enforcing rights contained in directives

EU law. This has particularly arisen through the passing of numerous directives which have been introduced under different Treaty Articles and which have had a major impact on UK employment law.

Directive 75/117

The equal pay directive was one of the first significant directives to gain force after the UK joined the EU. It expanded on Article 157 (at the time Article 119) on equal pay for men and women and identified the two types of equal pay, equal pay for equal work and equal pay for work of equal value. While the UK had passed the Equal Pay Act 1970 in advance of its successful application for membership, it was also the subject of infringement proceedings under Article 258 (at the time Article 169) since it had failed to properly implement the directive. This resulted in the passing of the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations 1983. It has now been replaced by the Recast Directive 2006/54 (see Chapter 10).

Directive 75/129

The Collective Redundancies Directive requires a process of consultation with employee representatives on large scale redundancies and also notification to appropriate public bodies. The Directive is now provides the significant rules on redundancy in the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992. It has also been replaced by a more recent Directive 98/59 (see Chapter 23).

Directive 76/207

The Equal Treatment Directive also developed out of Article 157. It required equal treatment of men and women in other conditions of work including transfer, training and promotion. The UK was also deficient in its implementation of this directive. Despite passing the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 the UK government had failed to fully implement this directive also because it had not taken into account the implications of there being differential retirement ages for men and women at that time. The directive has now been replaced by the Recast Directive 2006/54. Sex is now also a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010 (see Chapter 11).

Directive 77/187

This was the original Acquired Rights Directive and it introduced the idea that employee rights under a contract of employment should pass to the new employer on a transfer of the business. This was implemented in English law as the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 1981. The directive has subsequently been updated and the law on the area is now in Directive 2001/23. The UK regulations have also been modified and updated and now the law is in the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006 (see Chapter 18).

Directive 79/7

The Equal Treatment in Social Security Matters was introduced to ensure that the measures in the Equal Treatment Directive extended to social security matters including obviously a range of benefits. This was implemented by amendment to various social security legislation. The directive is now in the Recast Directive 2006/54 (see Chapter 11).

Directive 89/391

The Framework Directive on Health and Safety develops earlier EU health and safety provisions. EU health and safety law has been responsible for the introduction of the so- called 'six pack of regulations'. These were first in fact introduced in 1992 but most have subsequently been modified. They are the Management of HASAW Regulations 1999 (amended 2006), the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992, the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998, the Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations 1992, the Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 and the Health and Safety (Display Screen Equipment) Regulations 1992 (see Chapter 16.4.2).

Directive 93/104

This was the original Working Time Directive. It was in fact a health and safety directive introduced under the then Article 139. The UK government at the time tried hard to resist it claiming that it was in fact part of social policy from which it had an opt out following the TEU. However, this was disproved in an action in the ECJ. The Working Time Regulations were then introduced in 1998 after a change of government. The directive has now been replaced and updated in the Working Time Directive 2003/88 (see Chapter 16).

Directive 94/33

The Protection of Young People at Work Directive is self-explanatory in seeking to regulate the work of young people for health and safety purposes. It has been implemented as part of the range of regulations known as the 'six pack' particularly in the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 and amended in 2006 and also in the Working Time Regulations (see Chapter 16).

Directive 96/34

The Parental Leave Directive introduced the idea of parental leave and dependant care leave. It introduced a minimum floor of basic rights on such leave. The directive has subsequently been replaced and modified in the Parental Leave Directive 2010/18. The directive has been implemented into English law in a variety of regulations. These include the Maternity and Parental Leave (Amendment) Regulations 2001, the Paternity and Adoption Leave Regulations 2002, the Additional Paternity Leave Regulations 2010 as well as insertions in the Employment Rights Act 1996 (see Chapter 8).

Directive 97/81

The Part- Time Workers Directive was introduced to ensure that part-time workers would not be discriminated against by contrast with full-time employees. This reflects many findings of the Court of Justice more related to sex discrimination but, since parttimers are more likely to be women the employment of part-time staff on different conditions to full- time workers was a simple way of discriminating. The directive has been implemented into UK law in the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000 (see Chapter 14.6).

Directive 99/70

The Fixed- Term Workers Directive extends the principles of equality and nondiscrimination already prevalent in the case of sex and for part- time workers to fixed-term workers. The purpose of the rules is that employers should be prevented from using fixed-term contracts as a means of denying workers access to basic employment protections. The directive has been implemented in UK law in the Fixed- Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002 (see Chapter 14.7).

Directive 2000/43

The Race Directive was introduced to ensure equal treatment between employees irrespective of their race or ethnic origin. There were already quite extensive rules on race discrimination in the Race Relations Act 1976 which was drafted in very similar terms to the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. The directive in fact introduced a quite different definition of indirect discrimination which was much more beneficial to employees bringing such a claim. Race is now a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010 and claims can be brought in respect of all the types of prohibited conduct identified in the Act and in respect of all stages of employment (see Chapter 12).

Directive 2000/78

The Framework Directive on Equal Treatment in Employment and Occupation is a far reaching and far sighted directive which extends the whole scope of discrimination law. As a result Member States were required to extend basic principles of equal treatment to age, disability, religion or belief and sexual orientation. These were initially implemented into UK law in the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (Amendment) Regulations 2003, the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief ) Regulations 2003, the Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003, and the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006. Now all of these are protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010 and subject to regulation of the prohibited conduct identified in the Act. There are slightly different rules for different protected characteristics (see Chapter 13 and Chapters 14.2, 14.4 and 14.5).

Directive 2008/104

The Agency Workers Directive provides a range of rights for temporary agency workers so that they receive equal treatment to permanent employees where they are assigned. Clearly one way for an employer to avoid a worker receiving rights would be to hire temporary agency workers since these are rarely considered to be employees under the various tests of employment status (see Chapter 4.4). The directive has been implemented in UK law in the Agency Workers Regulations 2010 (see Chapter 14.8).

As can be seen from the above, EU law is significant to many of the chapters that follow and therefore to a very wide range of employment protections.

2.3.2 The development of EU labour law

Originally EU law was more concerned with the economics of the single market, up until fairly recently referred to as the common market. There was very little in the original Treaties that related to employment rights. In the original EC Treaty there was only quite limited reference to employment issues.

Article 118 (later Articles 137–140 following the Amsterdam Treaty but subsequently repealed following the Lisbon Treaty) stipulated that: without prejudice to the other provisions of this Treaty and in conformity with its general objectives, the Commission shall have the task of promoting close cooperation between Member States in the social field, particularly in matters relating to: employment, labour law and working conditions; basic and advanced vocational training; social security; prevention of occupational accidents and diseases; occupational hygiene; the right of association, and collective bargaining between employers and workers. However, there was no real movement on Article 118 until after the Single European Act 1986.

The other major provision in the original Treaty was Article 119 which is now Article 157 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). This was a much narrower principle with a narrower context of equal pay between men and women for equal work. This did have significant implications and is discussed in detail in Chapter 10.3. It also developed through Directive 76/207 (now in the Recast Directive 2006/54) into equal working conditions for men and women.

The next significant development was the Social Action Programme in 1974. The aims of the programme were to achieve full employment, to improve the standard of living and improved working conditions of all workers and to develop social dialogue in the workplace. However, the depressed economic conditions of the 1970s and 1980s meant that little progress was made. It was with a new Social Action Programme in 1984 and the Single European Act 1986 that further developments were made. This introduced Article 118A which provided as follows:

The Working Time Directive was passed under this Treaty Article although it was argued by the UK government as being social policy which the UK had been allowed to opt out of because of protocols inserted in the Treaty on European Union 1992. It also was the basis for many other developments in health and safety law.

Brian Bercusson in European Labour Law (Butterworths, 1996, p. 70) argues that there are in fact three possible interpretations of Article 118A:

It is inevitable that Member States would try to protest for the narrowest interpretation while the ECJ would interpret the provision that would bring the greatest number of EU citizens within the protection.

Another significant development of the time was the Community Charter for the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers 1989. Under the Charter the community (now the EU) was obliged to provide for the development of fundamental social rights of workers under a series of categories:

- ■ free movement of workers;

- ■ employment and remuneration;

- ■ improvement of living and working conditions;

- ■ social protection;

- ■ freedom of association and collective bargaining;

- ■ vocational training;

- ■ equal treatment for men and women;

- ■ information and consultation and participation of workers;

- ■ health protection and safety in the workplace;

- ■ protection of children and adolescents;

- ■ the elderly;

- ■ disabled persons;

- ■ Member States' action.

The Charter could not at the time be integrated into the Treaty because of the opposition of the UK government. The UK did eventually accept the Charter, but only following a change of government in 1997. Nevertheless, a new Social Action Programme was launched and the Charter was in fact instrumental in a number of initiatives in employment and industrial relations policy, which resulted in a number of directives during the 1990s. Included in these are directives on pregnancy and maternity (see Chapter 8.4), on working time (see Chapter 16.4.3), and on the framework agreements on parental leave (see Chapter 8.5), part- time work (see Chapter 14.6) and fixed-term work (see Chapter 14.7). Besides this the Charter also anticipated much of the potential of the fundamental individual employment rights in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, adopted in Nice in December 2000. The Charter can in any case be used as a tool for interpretation by the European Court of Justice in cases involving social and employment rights

Into the 1990s the Commission became more focused on problems associated with unemployment and with trying to tackle unemployment. It introduced a White Paper in 1993 entitled 'Growth, Competitiveness and Employment'. More significantly the Amsterdam Treaty 1999 inserted employment in Article 2 EC Treaty (now Article 3 TFEU) as one of the tasks of the 'Community'.

The more recent significant developments have been the Framework Race and Equal Treatment Directives which have extended the scope of discrimination into many more areas (see Chapter 14.1–14.5).

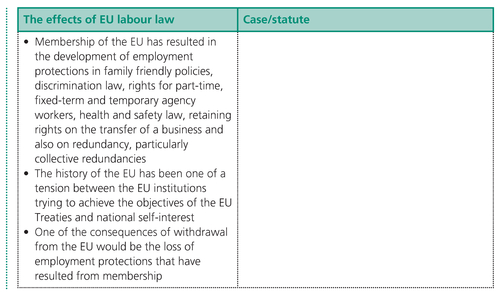

2.3.3 The effects of EU labour law

Membership of the EU has been amongst the most significant factors in developing employment protections. This has been particularly so in the case of modern statutory protections on maternity which previously existed in UK law but has expanded significantly as a result of EU law. EU law has also introduced rights in parental leave, paternity and adoption leave and pay for these also. It has also introduced the concept of dependant care leave. So there are a wide range of what have become known as the 'family friendly policies' that exist only as a result of EU law.

In the area of discrimination law the EU has had a massive influence on English law. Legislation on equal pay and later sex discrimination only arose in the first place because of application for membership and the need to be compatible with Treaty requirements of the time. Discrimination law of course has expanded massively since its origins in the simple proposition that men and women should receive equal pay for equal work. The ECJ was instrumental on numerous occasions in correcting the errors and shortcomings of UK implementation of EU discrimination law and the Commission also produced a logical definition of sexual harassment at a point where women claiming in England had to try to make a catch all principle in sex discrimination fit their particular circumstances. In the twenty-first century the EU has expanded the scope of discrimination law to cover age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race (where it has introduced a significantly wider definition of indirect discrimination than was the case with English law), religion or belief and sexual orientation. On gender reassignment and sexual orientation the Court of Justice had already identified that English law was inferior in dealing with the problems.

In its widening of discrimination law the EU has moved on at a pace since this.

In the case of atypical workers such as part-time workers, fixed-term employees and temporary agency workers directives have introduced rights of equal treatment with comparable employees that were otherwise absent from English law. In the case of part-time workers again rulings of the ECJ had already developed some protections.

In health and safety at work the EU has had an enormous influence. It has developed protections for young workers. It has introduced rules on working time which includes mandatory daily rest periods, a full day without work each week, and a minimum of four weeks paid holiday annually. It has also through a series of directives introduced the concept of compulsory risk assessment, regulation of the work environment, use of equipment and of personal protective equipment as well as modernising the use of display screen equipment.

The idea of protection of employment rights on the transfer of a business was created by the EU and dealt with the formerly abusive practice of employers who colluded on the sale and purchase of the business with the new employer being able to change all of the contractual rights and obligations of the workforce or even sack them with neither employer picking up any bill for redundancy payments. The EU has also in any case been instrumental in developing controls on redundancies, particularly collective redundancies and introducing the requirement for consultation.

Much of this was overcome by decisions of the ECJ. However, the current government, following the report of venture capitalist Adrian Beecroft has announced that it plans to review the regulations to remove the protection from workers whose jobs have been outsourced.

The history of the EU has been a history of a continuous tension between the EU institutions striving to achieve the objectives of the EU and the national self-interest of the Member States.

The EU has provided and for the last forty years has been the major provider of much needed developments of employment protections in the UK. EU employment law is only as good as the willingness of Member States to use and be bound by it and UK governments have shown a fair amount of reluctance over the years to embrace these developments.

It is common to see commentators on TV news and current affairs programmes suggesting that current economic and employment problems could be eased by a reduction in regulation and to blame the EU for the amount of regulation. Politically there has always been a rump of euroscepticism throughout UK membership. There is also a significant likelihood that there will in the near future be a referendum on membership and a greater likelihood of withdrawal from the EU than at any time before. It is important to remember that withdrawal from the EU would almost certainly be followed almost immediately by repeal of the various employment protections that have built up as a result of membership.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 1.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 1.3.

Storey, Tony and Turner, Chris, Unlocking EU Law 3rd edition. Hodder Education, 2011, Chapters 1, 4, 8 and 9.