19

Termination of employment (1) continuity, notice and dismissal

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the significance of continuity of employment

- ■ Understand how continuous employment is calculated for unfair dismissal purposes

- ■ Understand the significance of notice periods

- ■ Understand the statutory notice period in the absence of contractual notice

- ■ Understand the meaning of dismissal

- ■ Understand the three ways in which a contract of employment can be terminated by dismissal

- ■ Understand what is meant by a constructive dismissal

- ■ Understand the criteria for claiming constructive dismissal

- ■ Critically analyse the concepts of continuity of employment, notice and dismissal

- ■ Apply the rules on continuity of employment, notice and dismissal to factual situations

19.1 Continuity of employment

Nearly all employment protection rights depend on the employee having attained specific periods of continuous service. For unfair dismissal claims this has ranged from six months, one year and two years. While the last Labour government reduced the period to one year, since April 2012 it has been returned to two years by the present government (see Chapter 22.1).

Continuity is defined in section 212 Employment Rights Act 1996 and will not be affected by changes of conditions.

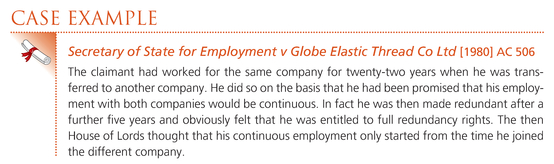

Continuity of employment is significant to statutory rights such as qualifying for redundancy or being able to claim unfair dismissal. In this way private agreements may be reached with employers extending continuous employment but this will not alter statutory rights.

Continuous employment begins with the contractual date of continuous employment rather than necessarily the actual date on which employment started which could be different.

Continuous employment is counted in complete weeks although length of continuous service is then counted in months and years.

Continuous employment ends with the ‘effective date of termination’ (EDT). However, the length of continuous service needed depends on the right being claimed. For unfair dismissal claims this is now two years again (see Chapter 22.1). Interestingly there was a point at which there was a possibility of any qualifying period of continuous employment being considered unlawful.

The House of Lords did find that there was a disparity in the order of ten women to nine men but in effect that this was insufficient to represent real discrimination.

Certain situations do not break continuous employment. These are identified in section 212(3) Employment Rights Act 1996.

So the three types of absences which will not break continuous service are:

- ■ periods of legitimate illness or injury;

- ■ temporary cessation of work;

- ■ arranged or customary absences.

As can be seen from section 212(4) above a sickness absence of more than twenty-six weeks could in effect break continuous service. If the employee leaves his job because he is incapable of work because of sickness and is reemployed within twenty- six weeks his service is then deemed to be continuous.

Temporary cessation of work refers to those situations where there are lay- offs within the industry but also other temporary breaks in employment.

Continuity of employment by custom has at times been prevalent in certain industries. In Gray v Burntisland Shipbuilding Co [1967] 2 ITR 253 such a custom was enforced whereby laid off workers in the shipbuilding industry returned when more work was available without a break in service. Arrangements to maintain continuity of employment can also be made between employer and employee for a variety of reasons.

However, there are situations that do break continuity of service and will be deducted from the overall period of employment:

- ■ working abroad

- ■ taking part in strikes

- ■ illegality.

Under section 215(1) Employment Rights Act 1996 employees who work outside the UK are generally excluded from employment rights and protections. Weeks spent working abroad where the employee is not an employed earner in the UK for the purpose of paying National Insurance contributions will not usually count towards continuity of employment.

Under section 216 Employment Rights Act 1996 where an employee is on strike the period that he is absent from work will not count towards his period of continuous employment but will not break continuity. Where continuous employment later has to be calculated the number of days lost through strike will be deducted in calculating continuous employment.

Continuous employment only counts legal employment so that an employee should be careful not to allow the contract of employment to become tainted with illegality or engage in a contract which is for an illegal purpose or employment rights may be lost as a result.

19.2 Notice and statutory notice periods

At common law the employer is bound to give reasonable notice. A contract of employment is a contract of continuous obligations so that the only way that it could logically end is if one party gives the other notice. The common law requirement merely refers back to the implied duty of mutual trust and respect. The period of notice required by either side in common law then is whatever is determined in the contract itself provided that it is reasonable. This is identified as information that must be in the statutory statement of particulars under section 1(4)(e) Employment Rights Act 1996. Courts may determine what amounts to a reasonable notice period in the circumstances.

If there is no express term on notice in the contract then the notice period will be determined by statute and in any case statute lays down minimum notice periods. These are identified in section 86(1) Employment Rights Act 1996.

So the statutory minimum notice periods are:

- ■ one week for at least one month and less than two years’ continuous service;

- ■ one week extra for each year’s continuous service up to a maximum of twelve weeks for twelve years’ service.

And the minimum statutory notice required of an employee is:

- ■ one week for an employee who has been employed for one month or more.

If the notice periods in the contract are greater than the statutory minimums then the contract notice periods will be followed and enforced by the courts. If the contract is less generous than the statutory minimums then the statutory periods from the Employment Rights Act 1996 will be followed. This latter point can actually prove critical for an employee who is being dismissed before qualifying periods for redundancy or unfair dismissal is reached.

In general once notice is given by either side it cannot be unilaterally withdrawn. However, it has been identified in Mowlem Northern Ltd v Watson [1990] IRLR 500 that employees who have been given notice can mutually agree with their employers to extend the notice period.

A payment in lieu of notice will also terminate the contract if the contract provides for that and if the payment properly reflects the required notice period. In Delaney v Staples t/a De Montfort Recruitment [1990] IRLR 86 where the claimant was summarily dismissed and given a cheque as payment in lieu Lord Browne- Wilkinson listed four circumstances where a lieu payment would be appropriate (see Chapter 8.1.2):

- ■ the employer gives the appropriate notice but does not require work from the employee (garden leave);

- ■ under the contract the employer is entitled to terminate the contract with notice or summarily on payment of a sum of money in lieu of notice;

- ■ an agreement between employer and employee to terminate the contract for an agreed payment;

- ■ the employer dismisses the employee summarily with a lieu payment.

The actual date of termination of the contract, the effective date of termination (EDT) is the date that the notice expires or the date of the lieu payment.

19.3 Dismissal

19.3.1 The statutory definition of dismissal

One of the first requirements in bringing a claim for unfair dismissal is to show that the contract of employment was terminated by a dismissal rather than as a result of another process such as frustration, a resignation by the employee or a mutual agreement between the parties (see Chapter 20). Dismissal is defined by statute in section 95 Employment Rights Act 1996.

So there are effectively only four ways in which a dismissal can occur:

- ■ The employer dismisses the employee giving him notice – the question here would be whether the appropriate notice has been given (see 19.2 above) and also of course whether the dismissal is fair.

- ■ The employer dismisses the employee without giving the appropriate notice – this generally would be summary dismissal and the question is whether the conduct of the employee is sufficient to warrant summary dismissal.

- ■ A fixed-term or limited- term contract comes to an end without renewal – the question is whether it is fair not to renew the contract.

- ■ The employee resigns and claims constructive dismissal – the question here is whether the employer’s conduct amounts to a significant breach of the contract.

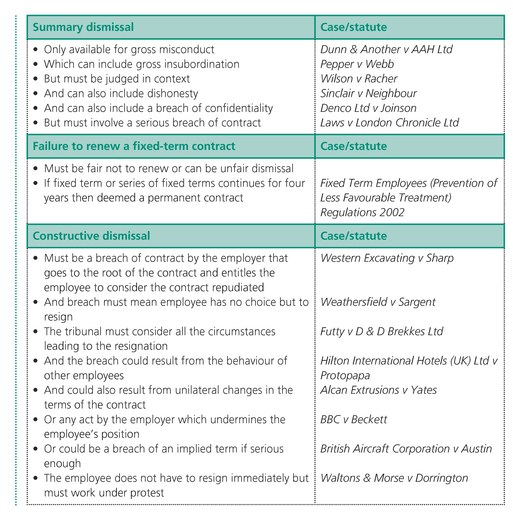

19.3.2 Summary dismissal

A summary dismissal is essentially an instant dismissal which has immediate effect ignoring contractual or statutory rights of notice. It follows that summary dismissal can be justified only in quite exceptional circumstances.

The only circumstances in which a summary dismissal can be justified is where there is gross misconduct by the employee. An employer might identify examples of gross misconduct in the contract of employment or in a booklet of disciplinary rules. However, for a summary dismissal to be justified the court would still need to accept that the particular behaviour did in fact amount to gross misconduct.

Serious negligence on the part of the employee, particularly if this causes damage, could be an example of gross misconduct. A failure to follow instructions leading to damage was held to be gross misconduct in Howe v Gloucester and Severnside Co-operative Society [1975] IRLR 17. Usually negligence would only amount to gross misconduct where it was continuing conduct. However, it was also accepted in Taylor v Alidair Ltd [1978] IRLR 82 a single act of negligence where the potential consequences were sufficiently serious could also amount to gross misconduct (see Chapter 22.4.1).

Traditionally it has been accepted that gross insubordination or a failure to follow lawful and reasonable orders could be classified as gross misconduct justifying summary dismissal.

What is socially acceptable, however, including swearing, changes over time so it is important to judge each case on its merits in the context of current standards to determine whether or not particular conduct justifies summary dismissal. As a result, although there is a duty of mutual trust and respect (see Chapter 7.2.5) swearing on its own may be insufficient to justify summary dismissal.

Certain types of misconduct breach commonly accepted standards of behaviour and will almost inevitably be classed as gross misconduct. A typical example is dishonesty at work or even out of work where it is relevant to the employment, which it will be in most cases.

Violence at work as well as drunkenness at work are also likely to amount to misconduct that justifies dismissal, although in general an employer is likely to investigate before dismissing (see Chapter 22.4.2). Any conduct which is likely to adversely affect the mutual trust and confidence between employer and employee is likely to be classed as gross misconduct and justify summary dismissal. A breach of confidentiality is a classic example of this.

On the other hand the employee’s behaviour must be sufficiently serious to amount to gross misconduct. If it could be dealt with through usual disciplinary procedures then a summary dismissal may not be lawful.

19.3.3 Failure to renew a fixed-term or limited-term contract

A fixed-term contract is one that lasts for a specific duration. A limited-term contract is one that lasts until performance of a specific task is completed or until an occurrence of a specific event. In either case if the contract is not renewed then this amounts to a dismissal under section 95 Employment Rights Act 1996.

While the contract is not intended to be permanent, it may still need to be tested whether the failure to renew is fair in the circumstances. In this way it is important to be able to show that there is a genuine need for the contract only to be temporary or only for a specific task. The employer should not use a fixed-term contract as a disguise to deprive the employee of statutory rights

Now under the Fixed Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002 where an employee is employed for four years or more under a single fixed term or successive fixed terms then the contract is deemed to be one of indefinite duration unless there is objective justification for the contrary.

19.3.4 Constructive dismissal

A constructive dismissal occurs in situations where the employee effectively resigns but in circumstances where he is entitled to do so because the employer’s conduct amounts to a significant breach of the contract and therefore an unlawful repudiation of the contract. The employee first of all needs to make it clear that he considers it a constructive dismissal or he may lose his chance of a remedy.

The starting point for showing that there is indeed a constructive dismissal is Lord Den-ning’s judgment in Western Excavating v Sharp [1978] QB 761 which explains what conduct by the employer entitles the employee to feel that there is a repudiatory breach.

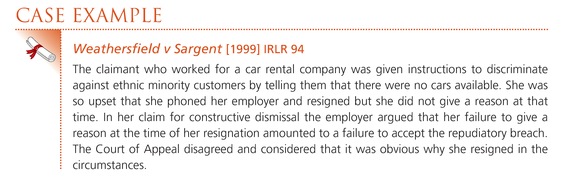

What amounts to a significant breach is for the tribunal to determine and it will only be a constructive dismissal where there is no alternative to the employee’s resignation in the circumstances because the employer’s breach is a significant one going to the root of the contract rather than as was once thought merely unreasonable behaviour by the employer.

Obviously it is also not merely the actions of the employer that give rise to a repudiatory breach justifying a claim of constructive dismissal. The tribunal needs to consider the full circumstances in which the event caused the employee to resign.

It also does not need to be the employer’s conduct that amounts to the breach. It could result from the conduct of another employee where the employer is responsible for the behaviour of the other employee.

It is quite common for the constructive dismissal to result from unilateral changes in central express terms of the contract such as pay, hours and duties.

Another act by the employer which undermines the employee’s position and could amount to a repudiatory breach justifying a claim of constructive dismissal is demotion of the employee.

It is also clearly possible for the constructive dismissal to result from the employer breaching one of the implied terms if this amounts to a significant breach. This is more straightforward where the duty is practical in nature.

An employee does not necessarily have to leave immediately to claim constructive dismissal as long as the breach was significantly serious and it was still the actual cause of the resignation although there is of course always a risk that the tribunal might consider that the employee has accepted the situation.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapters 13, 15 and 17.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 8.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 4.3.