11

Protection from discrimination (2) sex discrimination

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the background to the law on sex discrimination in employment and its limitations prior to the Equality Act 2010

- ■ Understand the definition of sex under the Equality Act 2010

- ■ Understand the different types of prohibited practices under the Equality Act 2010 as they relate to employees

- ■ Understand the contexts in which discrimination on grounds of sex can occur in employment

- ■ Understand the nature of occupational requirements in relation to sex

- ■ Critically analyse the area

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

11.1 The origins and aims of sex discrimination law

Prior to the Equal Pay Act 1970 there was no protection against discrimination on sex. UK sex discrimination law arose because of application for membership of the EU (at the time the EC). In EU law protection from sex discrimination came in the Equal Treatment Directive 76/207. Now this is contained in the Recast Directive 2006/54.

Occupational sexism could be any discriminatory practices, statements, actions or behaviour based on a person’s sex that occurs in the context of employment. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination (see Chapter 10). Eurostat found a persisting gender pay gap of 17.5 per cent on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008. Similarly, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found that female full- time employees earned 17 per cent less than their male counterparts across OECD countries in 2009.

In 2008, the OECD found that while female employment rates have expanded considerably and the gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed virtually everywhere, on average, women still have 20 per cent less of a chance to have a job and are paid 17 per cent less than men. The report also stated: ‘[In] many countries, labour market discrimination – i.e. the unequal treatment of equally productive individuals only because they belong to a specific group – is still a crucial factor inflating disparities in employment and the quality of job opportunities ... Evidence presented in this edition of the Employment Outlook suggests that about 8% of the variation in gender employment gaps and 30% of the variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by discriminatory practices in the labour market.’

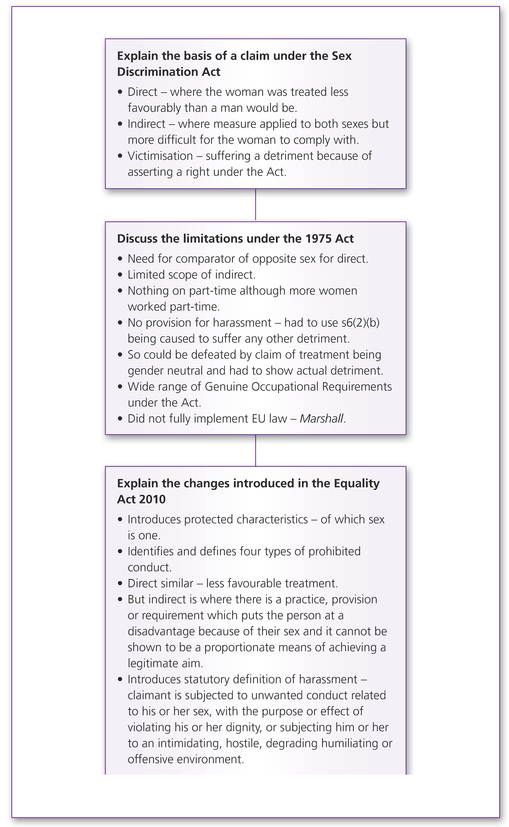

11.2 The different types of sex discrimination

Sex is now a protected characteristic under section 4 of the Equality Act 2010. Section 11 defines who is included within this protected characteristic.

While it may commonly be expected that women are more likely to be discriminated against, as section 11(a) identifies the Act applies equally to both sexes and this was the case in the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. If a man is subjected to a detriment because of his sex then he will have a possible claim.

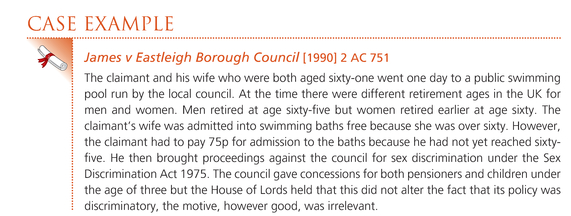

The test for whether something is discriminatory is an objective one so that the motive for the discrimination is irrelevant, the test being whether the claimant would have been treated the same if it was not for their sex.

11.2.1 Direct discrimination

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.1 under section 13 Equality Act 2010 a person would be directly discriminated against because of their sex if:

- ■ he or she is treated less favourably than a person of the opposite sex would be.

Direct discrimination can arise in a variety of ways. It can inevitably concern denying a woman an opportunity that would be available to a man simply because of her sex. Providing that the claimant is treated less favourably than an employee of the opposite sex then there could be direct discrimination.

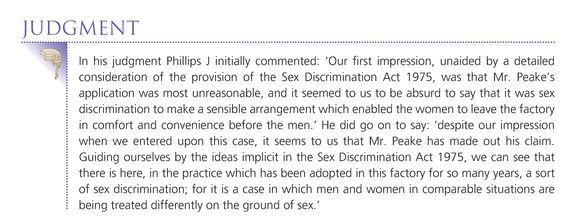

The claimant has to show that there is less favourable treatment. As a result there logically has to be a comparator of the opposite sex. The courts have considered the situation where there is no appropriate comparator.

It has even been questioned in the past whether, even though there has been direct discrimination, the matter is too trivial or not deserving of a remedy.

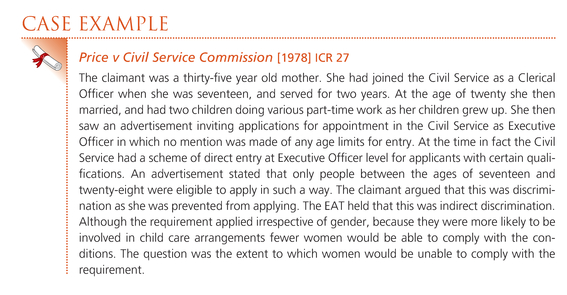

11.2.2 Indirect discrimination

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.2 under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of their sex if:

- ■ he or she is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to his or her sex;

- ■ which applies to other employees not sharing the characteristic but puts the claimant at a disadvantage compared with persons of the opposite sex;

- ■ and it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

Obviously the first part of the test for indirect discrimination is whether there is a provision, practice or criterion which is common to both men and women. The fact that will make it discriminatory is that a person of one sex has a lesser chance of complying because of their sex.

It is plain that, because it is mostly women who are associated with child care arrangements that provisions, practices or criteria in their daily working arrangements that might interfere with their ability to manage those child care arrangements may well be seen as indirect discrimination. Inevitably there would have to be a disadvantage suffered.

Of course the other part of the definition of indirect discrimination concerns whether the practice or criterion is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. It is then possible to show that the discrimination was justified.

The significant fact is that there is less favourable treatment. If a policy applies regardless of the employee’s sex then it is unlikely to be indirect discrimination.

11.2.3 Harassment

Sex is one of the protected characteristics identified in section 26(5) Equality Act 2010 and therefore an action for sexual harassment is possible.

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.3 under section 26 Equality Act 2010 a person would suffer sexual harassment if:

- ■ he or she was subjected to unwanted conduct related to his or her sex; and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his dignity, or subjecting him or her to an intimidating, hostile, degrading humiliating or offensive environment.

This is a significant development from the original law on sexual harassment. Traditionally there had been no distinct provision made for sexual harassment in the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. The only possibility was under section 6(2)(b) that the person had been subjected to ‘any other detriment’. As a result women could only bring a successful action if they could show that they had suffered a detriment. In contrast the EU (at the time EC) did produce a Code of Practice containing a definition ‘unwanted conduct of a sexual nature, or other conduct based on sex affecting the dignity of women and men at work’.

In the early claims the problem for a woman alleging sexual harassment was that she had to show that she had been treated less favourably than a man in the same circumstances would be and that she had suffered a detriment

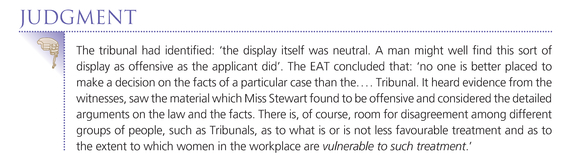

Any form of unwanted conduct which is unwelcome and offensive may be seen as harassment and give rise to a claim of sexual discrimination. The perception of the claimant is also significant. The case above the detriment involved the creation of an unwanted and hostile environment, but harassment can also occur as a result of the humiliation of the claimant.

A significant problem for women trying to bring claims for sexual harassment at this time was the argument that was often accepted by tribunals that certain behaviour was gender neutral. The extension of the argument is that a man could be as offended by it as a woman as a result of which there would be no detriment and no less favourable treatment of the woman.

The argument completely misses the point. The nude pictures were of women and therefore it is arguable whether there was any gender neutrality and only women would feel vulnerable as a result of the situation. Because a detriment was required it is also the case that a claim could be defeated by reference to the woman’s attitudes to sexual matters and her own sexual history.

11.2.4 Victimisation

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.4 under section 27 Equality Act 2010 a person would have been victimised against because of their sex if:

- ■ he or she has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he or she has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he or she has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he or she has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he or she has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his or her employer or another person has contravened the Act.

For a claim of victimisation the claimant only has to show that she has suffered a detriment because she has done one of the protected acts under section 27.

However, it will not be victimisation where the employer acts reasonably in trying to reach a compromise in a dispute with an employee in trying to get them to reach a settlement.

11.3 The situations in which discrimination is prohibited in employment

Section 39 Equality Act 2010 deals with discrimination in employment. The section makes the following provisions.

There are clearly three points in relation to employment where discrimination could be a significant issue:

- ■ in the recruitment and selection of staff;

- ■ during employment;

- ■ on termination of employment.

11.3.1 Recruitment and selection of staff

Applying the full definition from section 39(1) Equality Act 2010 an employer is not allowed to discriminate:

- ■ in the way in which it decides who it will offer employment;

- ■ in the terms on which the employment is offered;

- ■ by not offering a person employment.

Jobs should clearly be available generally to both sexes unless there is an occupational requirement. If the selection procedure is not impartial then this is likely to be discriminatory.

In this respect questions at interviews can be critical since they must only relate to the actual work and be gender neutral unless sex is a genuine determining factor.

On the other hand in Gates v Wirral Borough Council (unreported) a woman was asked at her job interview, about her relationship with her husband and whether she intended to have a family in the near future. Since the same questions were not put to any male candidate the tribunal found that the questions were discriminatory.

Clearly it would also be discrimination to refuse a person solely because of their sex. In Batisha v Say [1977] IRLR 6 a woman was turned down for a job as a cave guide because, as it was explained, ‘it is a man’s job’. This was a clear act of discrimination. Of course if the refusal to employ is actually for another reason then there is unlikely to be discrimination. In Steere v Morris Bros a woman was refused work as an HGV driver and claimed discrimination. The defendant was able to show that the refusal was because the woman lived too far away from their premises.

The ECJ in Dekker v Stichting Vormingscentrum voor Jong Wolwsassenen (VJV Centrum) Plus [1990] (C- 177/88) ECR 1-3941 also identified that a refusal to appoint a woman because she was pregnant was in breach of the then Equal Treatment Directive 76/207 and so amounted to sex discrimination. Pregnancy and maternity is now a protected characteristic under section 18 Equality Act 2010 (see Chapter 9.2). There are extensive rules covering pregnancy and maternity. These are covered in Chapter 8.4.

11.3.2 During employment

Applying the full definition from section 39(2) Equality Act 2010 during employment an employer is not allowed to discriminate:

- ■ by giving the claimant less favourable terms than that of an employee of the opposite sex;

- ■ in the way that it provides opportunities for promotion, transfer, training or any other benefit, service or facility;

- ■ by subjecting the claimant to any other detriment.

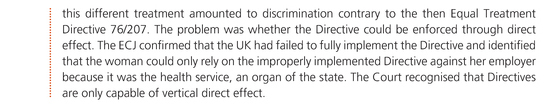

Any form of differential treatment during employment based on sex could amount to discrimination. This is an area where EU law has been significant in developing rights, originally under the Equal Treatment Directive 76/207.

Originally the fact that directives could only be vertically directly effective against the state or an emanation of the state meant that there was an anomaly in the law in that the possibility of enforcing rights given in a directive would not be available where the employer was a private body.

The problem was later overcome by the ECJ in developing the principle of state liability. Equal treatment now falls under the Recast Directive 2006/54. While the cases above are illustrating EU law principles of direct effect as well as concerning discrimination during employment they are also significant in illustrating that the English court was prepared to allow an injustice to occur where the ECJ was not.

Any denial of similar opportunities for promotion or training or transfer that are enjoyed by employees of the opposite sex are likely to amount to discrimination.

Similarly, imposing conditions on one sex that are not imposed on the opposite sex may be discriminatory if they cannot be justified.

Another area that may give rise to claims of discrimination is differential dress codes for men and women. If there is no detriment or there is a justification then they may be unsuccessful. In Schmidt v Austicks Bookshops Ltd [1977] IRLR 360 the employer’s dress code included a prohibition on female staff wearing trousers. This was held not to be discrimination since there was no detriment.

In Burrett v West Birmingham Health Authority [1994] IRLR 7 a nurse claimed that having to wear a hat which was stiff and was of no practical significance when a male nurse did not have to wear such a hat was discrimination. When she complained she was then transferred to a different department where she had less chance of overtime. The EAT held, however, that it was not less favourable treatment, the mere fact that men and women had different dress codes was not in itself discriminatory.

Traditionally sexual harassment claims were based on less favourable treatment and suffering a detriment. It has been accepted that even a single act of harassment could be both and thus be the basis of a claim.

11.3.3 On termination of employment

A discriminatory dismissal is identified also in section 39(2). Clearly any dismissal based on a person’s sex would be unacceptable. The claimant must show that the dismissal was for reasons of his or her sex for a successful claim. In Grieg v Community Industry [1979] IRLR 158 (see 11.2.1 above) the young women was dismissed on the first day of work but it was specifically because of her sex and so was a discriminatory dismissal.

In sexual harassment cases a woman may feel that she has no choice but to resign because the behaviour is unacceptable. This would be a constructive dismissal (see Chapter 19) and could amount to a discriminatory dismissal. This was the case in Insitu Cleaning Co Ltd v Heads [1995] IRLR 4 (see 11.2.3 above).

As has already been identified in 11.3.2 dress codes can also be discriminatory if they have the result that they treat a person of one sex less favourably than a person of the other sex would be.

The judgment would appear to be based on a value judgment of what constitutes smartness and convention rather than on an objective standard applied regardless of gender. Again perceptions or prejudices of employers might be an issue leading to discrimination. Another common prejudice is that men are breadwinners of families. This could be factually accurate but it is dangerous to base a discriminatory practice on it.

11.4 Lawful justifications for sex discrimination

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.5 under schedule 9 Equality Act 2010 an employer will be able to justify the alleged discrimination when:

- ■ there is an occupational requirement;

- ■ the application of the requirement is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim;

- ■ the person to whom the employer applies the requirement does not meet it or the employer has reasonable grounds for not being satisfied that the person meets it.

There were a variety of ‘genuine occupational qualifications’ under section 7 of the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. Some of these will survive as occupational requirements under schedule 9 of the Equality Act 2010 if they are a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

One is where the job requires authenticity of physiology. This will obviously be the case with films and plays where the producer requires a female actor to play a female role and a male actor to play a male role.

Another is where the nature of the job requires it to be done by one sex in order to preserve decency or privacy. This could be because it could prove objectionable for there to be contact with a member of the opposite sex. Two cases illustrate the same point but involving different sexes.

On the contrary where the job requires that the employees are in close contact in a state of undress then it will be accepted that this is a necessary occupational requirement for preserving decency and privacy

Another possible occupational requirement concerns private residencies. If the job involves living in a private home and needs to be done by a person of a particular sex because objection might reasonably be taken to allowing someone of the opposite sex the degree of personal contact or knowledge of the employer’s private affairs which the job necessarily entails. This could obviously cover professional carers.

Another is where the job involves performance of duties in another country the laws or customs of which would make it difficult for one particular sex to do the work. This is usually going to be a woman.

Another interesting possibility has been discussed within the context of EU law.

Figure 11.1 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of discrimination on grounds of sex

11.5 Discrimination on marital status

Discrimination on marital status was originally unlawful under section 3(1) Sex Discrimination Act 1975. Now marital status and civil partnership are a protected characteristic under section 4 of the Equality Act 2010. Section 8 defines who is included within this protected characteristic.

Direct discrimination

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.1 under section 13 Equality Act 2010 a person would be directly discriminated against because of his or her marital status or civil partnership if:

- ■ he or she is treated less favourably than a single person would be.

Obviously, in the context of employment this less favourable treatment could either be in the recruitment and selection of staff, during the employment or on dismissal. So it could involve failing to employ somebody because of their marital status, subjecting them to different terms of employment because of their marital status or dismissing them because of their marital status.

An example of discrimination during employment might result from a failure to promote the employee because of his or her marital status.

The employer in the above case was making prejudiced assumptions about whether a married couple can work together. The example of a discriminatory dismissal below is also interesting because it features a similar prejudice.

Indirect discrimination

Indirect discrimination is also possible. Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.2 under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of their marital status or civil partnership if:

- ■ he or she is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to his or her marital status or civil partnership;

- ■ because it puts him or her at a disadvantage compared with single people;

- ■ it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

In Chief Constable of the Bedfordshire Constabulary v Graham [2002] IRLR 239 above the EAT also decided that there could have been indirect discrimination because evidence showed that there was a higher proportion of female officers in relationships than male officers.

Indirect discrimination might also result from a practice or criterion which is based on the prejudice of the employer.

Harassment

Harassment will only apply in relation to marital status under section 26(2) Equality Act 2010 where a person suffers harassment because of his or her marital status or civil partnership if:

- ■ he or she was subjected to unwanted conduct of a sexual nature related to his or her marital status or civil partnership; and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his or her dignity, or subjecting him or her to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

Victimisation

Finally victimisation also applies in the case of marital status. Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.4 under section 27 Equality Act 2010 a person would have been victimised against because of his or her marital status or civil partnership if:

- ■ he or she has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he or she has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he or she has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he or she has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he or she has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his employer or another person has contravened the Act.

Figure 11.2 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of discrimination on the grounds of marital status or civil partnership

Single employees

While marital status is a protected characteristic, being single or unmarried is not, so it has always been possible to discriminate against a single person. In Sun Alliance & London Insurance Co v Dudman [1978] IRLR the court identified that, where a firm makes preferential mortgage facilities available to married men then it must do so also for married women, otherwise there would be discrimination. On the other hand it was perfectly permissible to exclude single employees from the scheme.

Similarly in Bavin v NHS Pensions Trust Agency [1999] ICR 1192 which involved survivor pension rights for unmarried partners the surviving unmarried partner of the female deceased was a transsexual who had undergone gender reassignment from female to male. The partners were unmarried because under the law at that time neither same sex couples nor transsexuals could marry. The EAT held that in law the transsexual was a female and had been discriminated against only on the basis of her single status which was perfectly legal. The reason for the single status was considered irrelevant to the issue by the court.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 4.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 3.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 5.