3

Institutions and procedures

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand which cases hear claims or appeals on employment law issues

- ■ Understand that the Court of Justice of the European Union only hears references from a Member State court or tribunal on employment law issues or infringement proceedings against a Member State that breaches its EU obligations

- ■ Understand the role of other important institutions

- ■ Understand the various procedural elements of a claim on an employment law issue

- ■ Understand the available remedies

- ■ Critically analyse the area

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

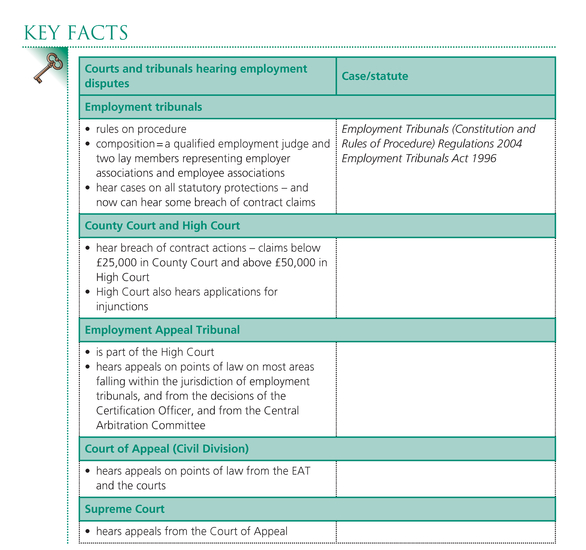

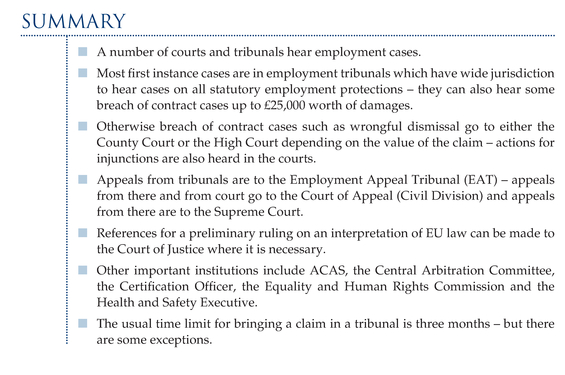

3.1 Courts and tribunals hearing employment disputes

Disputes at first instance involving issues of employment law can be heard in employment tribunals, the County Court and the High Court. Where the case is heard depends on the issue in question. In general terms cases involving statutory employment protections will be brought as claims in employment tribunals. This could include numerous types of claim such as equal pay, discrimination, redundancy, unfair dismissal, maternity rights and others. Disputes involving a breach of contract and a claim for damages will usually go to court, although following the Employment Tribunals Extension of Jurisdiction (England and Wales) Order 1994 it is possible for some breach of contract claims to be brought in tribunals where the maximum award would be £25,000.

3.1.1 Employment tribunals

Employment tribunals were originally established under the Industrial Training Act 1964 and until 1998 were known as industrial tribunals. Procedure in employment tribunals is now governed by the Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2004 as amended and the Employment Tribunals Act 1996.

They comprise an employment judge and two lay members. The employment judge can be a barrister or solicitor and can sit either full-time or part- time. The lay members only sit part- time and one will represent employers' associations and one will represent employee associations so that there is a balance of views and expertise. It is possible also for the employment judge to sit with only one lay member if both parties to the dispute agree. It is also possible for the employment judge to sit alone in unfair dismissal cases. The employment judge should be impartial and not have any connection with any of the parties that appear before him.

Employment tribunals have wide jurisdiction to hear cases including the following statutory provisions:

- ■ the Employment Agencies Act 1973;

- ■ the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974;

- ■ the Industrial Training Act 1982;

- ■ the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992;

- ■ the Employment Rights Act 1996;

- ■ the National Minimum Wage Act 1998;

- ■ the Employment Relations Act 1999;

- ■ the Equality Act 2010;

- ■ the Suspension from Work (on Maternity Grounds) Order 1994;

- ■ the Working Time Regulations 1998;

- ■ the National Minimum Wage Regulations 1999;

- ■ the Maternity and Parental Leave Regulations 1999;

- ■ the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000;

- ■ the Fixed-Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002;

- ■ the Paternity and Adoption Leave Regulations 2002;

- ■ the Flexible Working (Eligibility, Complaints and Remedies) Regulations 2002;

- ■ the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006;

- ■ the Agency Workers Regulations 2010.

There is no financial legal assistance available for representation in employment tribunals. A claimant might be able to gain support and representation from their trade union and help may possibly be available from a Citizens Advice Bureau or from a Law Centre. In limited circumstances in discrimination claims the Equality and Human Rights Commission might fund a case or provide representation. However, this does indicate yet another imbalance in the employment relationship.

3.1.2 County Court and High Court

Claims arising from statutory employment protections are heard in employment tribunals. Claims involving breach of contract can be made in the normal courts, either the County Court or the High Court.

In many cases such claims will be brought in the County Court but where the case is heard depends on the amount of damages which are being sought. In practice there is a presumption that where damages will be less than £25,000 then the claim will be heard in the County Court. Similarly there is a presumption that where damages will be more than £50,000 then the claim will be heard in the High Court.

The High Court will also hear actions by employers to gain injunctions to prevent strike action. It is likely also that applications to secure injunctions to prevent a restraint of trade will be heard in the High Court.

On the other hand it must also be remembered that much industrial health and safety law concerns criminal sanctions so in these instances the Crown Court and the Magistrates' Courts could be involved in employment matters.

3.1.3 The Employment Appeal Tribunal

The Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) was originally created in 1975. It comprises High Court judges and other members who have specialist knowledge of industrial relations. These are of two types: those that represent employers’ organisations and those that represent employee organisations.

The EAT is an appeal court and a superior court of record. It has civil jurisdiction to hear the following appeals:

- ■ appeals on points of law on most areas falling within the jurisdiction of employment tribunals (this does not include appeals relating to improvement notices and prohibition notices because these involve criminal offences and so any appeal would have to be on a point of law to the Divisional Court of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court);

- ■ appeals from the decisions of the Certification Officer (where an appeal could also be based on fact as well as law);

- ■ appeals from the Central Arbitration Committee.

Appeals are heard by a judge and either two or four lay members so that there are an equal number representing employer organisations and employee organisations. This can be varied with the consent of both parties. Also, where a tribunal hearing has been presided over by a single employment judge rather than a full panel, the appeal in the EAT does not have to be in front of a full panel.

A party can appear in person or be represented by a lawyer or a representative of either a trade union or an employers' association or by any other representative that the party selects.

If the Registrar thinks that an appeal has no reasonable prospect of success or that it amounts to an abuse of process then he can inform the appellant that the appeal will not proceed.

In respect of precedent the EAT is not bound by its own previous decisions. However, it is of course bound by applicable precedents of the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court (and of course any of the former House of Lords). It will also have to apply principles of laws decided by the Court of Justice of the European Union.

3.1.4 The Court of Appeal (Civil Division)

An appeal against a decision of a County Court, the High Court or the Employment Appeal Tribunal could go to the Court of Appeal (Civil Division). Practicality and cost would mean that in most instances the Court of Appeal is likely to be the final appeal.

3.1.5 The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court was created by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 and it replaced the House of Lords in October 2009. It is the highest court in the English court hierarchy except where a case concerns an issue which is governed by EU law in which case the Court of Justice of the European Union is the superior court.

The court hears appeals and is the final appeal court in the court hierarchy. It hears appeals on points of law generally where an existing precedent is in question or where there is an issue of statutory interpretation.

3.1.6 The Court of Justice of the European Union

The Court of Justice could be involved in UK employment law in either of two ways.

First the court has jurisdiction under Article 267 TFEU to hear references from courts or tribunals of Member States for preliminary rulings on the proper interpretation of provisions of EU law.

- ■ Under the reference procedure in Article 267(2) any court or tribunal may make a reference to the Court of Justice where it is necessary for the resolution of the dispute.

- ■ By Article 267(3) a court of last resort must make a reference where it is necessary to resolve the case.

The court provides its answer to the question posed by the national court or tribunal and it is then for the national court or tribunal to apply the legal principle as explained by the Court of Justice to the facts of the case. There are numerous examples of cases involving a reference to the Court of Justice in many of the chapters that follow.

Second the Court of Justice could become involved where a Member State, for the purposes here the UK, is in breach of its EU obligations for example by failing to implement at all or to fully implement a directive. In that situation the Commission can institute infringement proceedings under Article 258 TFEU. In practice there would be an attempt to persuade the Member State first to follow its obligations before the issue would actually end up in the court as Article 258 proceedings. A classic early example of this was Commission v UK 61/81 where the Equal Pay Act 1970 was found to be deficient since it failed to provide a means of bringing an action for equal pay for work of equal value as required by the then Equal Pay Directive 75/117 (now subsumed in the Recast Directive 2006/54). The outcome of the proceedings was that the UK government passed the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations 1983 and inserted a new section 2(4) in the Equal Pay Act 1970.

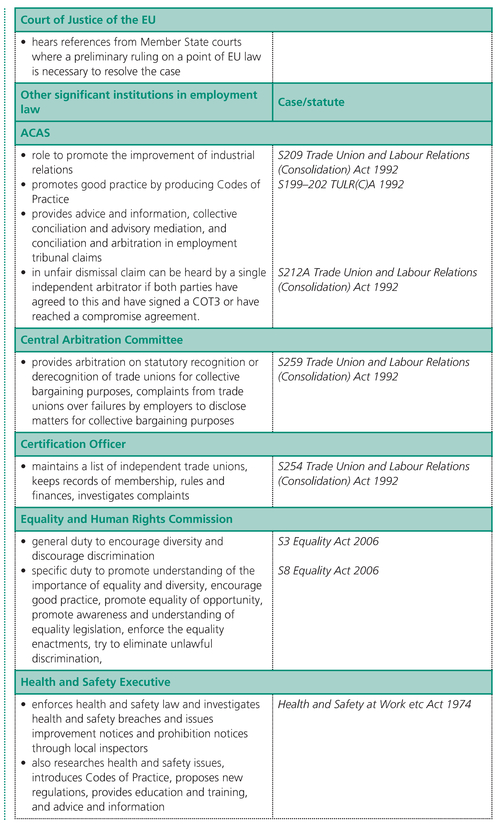

3.1.7 Other significant institutions in employment law

The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS)

ACAS was created as an independent body in the Employment Protection Act 1975. It is now governed by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992.

Its work is directed by a council which comprises a chairman, three members who are appointed after consultation with employers' associations, three members who are appointed after consultation with workers' associations and three neutral appointments that are usually academics. There are also two further members who can be appointed by the Secretary of State.

While ACAS is publicly funded and performs functions on behalf of the Crown, it is nevertheless not subject to any ministerial control. Under section 209 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 its role is to promote the improvement of industrial relations. There are four key aspects to its work:

- ■ promoting good practice;

- ■ providing advice and information;

Figure 3.1 Diagram illustrating the courts or tribunals hearing employment cases

- ■ preventing and resolving disputes through collective conciliation and advisory mediation;

- ■ providing conciliation and arbitration in disputes brought before employment tribunals.

Promoting good practice

ACAS produces an annual report which is presented to Parliament but which is also published and therefore freely available. It also produces numerous publications on good industrial practice in a variety of contexts.

Under sections 199–202 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 it also produces Codes of Practice including Codes on disciplinary and grievance procedure, time off for trade union duties and activities, and disclosure of information to trade unions for collective bargaining purposes. After the Codes are approved by the Secretary of State they are then published.

Under section 207 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 the Codes are admissible in tribunal hearings. While they are not legally binding they can be taken into account by tribunals when they are arriving at decisions.

Providing advice and information

ACAS also produces numerous booklets providing advice on different employment related matters which are vital sources of information. It is also able to respond to requests for advice from individuals or organisations and to provide specific advice as it thinks appropriate in the circumstances.

Collective conciliation and advisory mediation

ACAS can also provide assistance where a trade dispute either exists or is imminent. It can do so at the request of either party to the dispute or indeed can intervene without request. The purpose of ACAS involvement is to try to reach an appropriate settlement of the dispute by conciliation. It is also able to provide conciliation services in disputes over recognition of trade unions.

Conciliation and arbitration in claims before employment tribunals

A conciliation officer from ACAS can intervene in claims to employment tribunals. When a claim has been lodged with a tribunal a copy is then sent to the conciliation officer. The conciliation officer can then try to promote a settlement either because he has been requested to do so by either of the parties or because he believes that he has a reasonable prospect of success. In determining the issue ACAS will take into account:

- ■ whether there is a prima facie cause of action;

- ■ whether the parties have made an attempt to resolve the issue through internal grievance or disciplinary procedures;

- ■ whether intervention by ACAS might undermine any existing agreements or procedures;

- ■ the cost of intervention bearing in mind the number of disputes that ACAS might be called on to intervene in at that time.

There is also a pre-claim conciliation service where employers or employees can contact ACAS and seek help in an unresolved dispute prior to any formal claim being lodged with a tribunal.

In unfair dismissal claims only section 212A Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 allows for the claim to be heard by a single independent arbitrator if both parties have agreed to this and have signed a COT3 or have reached a compromise agreement. In such circumstances the parties waive their rights to argue jurisdictional issues. As a result the procedure is not suitable for those claims which include jurisdictional or other complex issues. The parties submit a written statement to the arbitrator. The process is then inquisitorial and the decision of the arbitrator is binding in most instances.

The Central Arbitration Committee

The Committee was first created in the Employment Act 1975 but is now governed by section 259 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992. It comprises a chairman, ten deputy chairmen, twenty-seven representatives of employers’ associations and twenty-three representatives of employee associations.

It acts as an independent source of arbitration dealing with statutory recognition or derecognition of trade unions for collective bargaining purposes, complaints from trade unions over failures by employers to disclose matters for collective bargaining purposes.

It can also arbitrate in disputes referred to it by ACAS where both parties have agreed to submit themselves to arbitration.

The Certification Officer

This post was first established in 1975 and is now governed by section 254 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992. The Certification Officer has a number of roles in relation to trade unions. He maintains a list of independent trade unions issuing them with certificates of independence as well as keeping records of their membership, copies of their rules and records of their finances. He also has powers to investigate complaints relating to election of trade union officials or other ballots and to oversee the setting up of political funds, as well as being able to investigate allegations of fraud.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission

The Commission was created in the Equality Act 2006 and replaced the former Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC), Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) and Disability Rights Commission (DRC). It does, however, have much wider powers than any of the former bodies.

The Commission has a general duty identified in section 3:

The Commission is responsible for promoting equality and tackling discrimination in all those areas identified as protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010 (see Chapters 9, 11, 12, 13 and 14), and also for promoting human rights under the Human Rights Act 1998.

The Commission is staffed by sixteen Commissioners and has the power to appoint advisory committees and to issue Codes of Practice. It also prepares a strategic plan for its activities as well as preparing a three-yearly report which outlines problem areas and suggests proposals for improvement. It also has powers to carry out investigations and to issue unlawful act notices.

The Health and Safety Executive

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) was originally created in the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 together with the Health and Safety Commission. In 2008 the two bodies were merged. The HSE comprises eleven non-executive members, three appointed following consultation with employers' associations, three following consultation with employee associations, one after consultation with local authorities and four following consultation with professional bodies.

The HSE makes arrangements for the general purpose of promoting and ensuring health and safety at work. In particular the HSE's role includes:

- ■ researching health and safety issues;

- ■ introducing Codes of Practice on health and safety at work;

- ■ suggesting new health and safety regulations;

- ■ providing and promoting education and training on health and safety;

- ■ providing advice and information on health and safety issues;

- ■ assisting people to pursue matters related to health and safety at work.

The HSE also has powers of investigation using local authority inspectors and of enforcement of the statutory provisions through improvement notices and prohibition notices. It can also bring prosecutions for breaches of health and safety laws (see Chapter 16.4).

3.2 Employment tribunal procedure

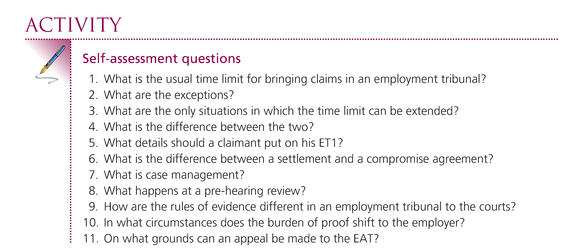

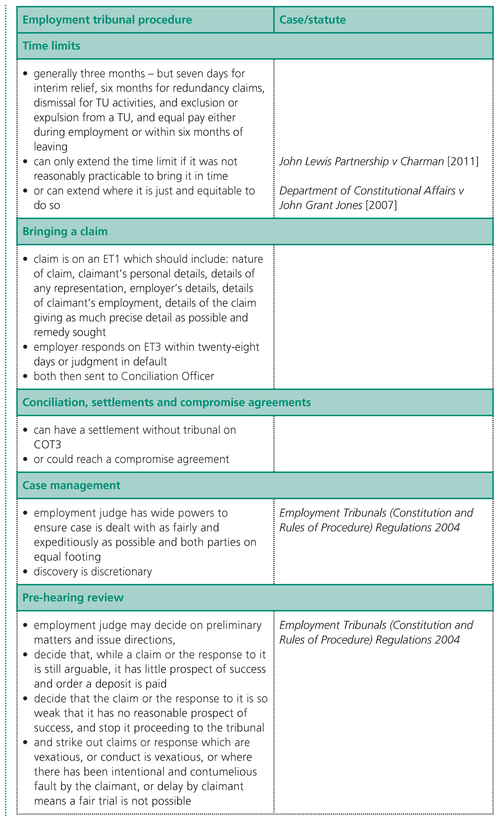

3.2.1 Time limits

Time limits govern employment tribunal procedure in exactly the same way that they govern any other form of civil dispute resolution procedure. An employee seeking to enforce an employment right or claiming a breach of any such right must bring his claim within the strict time limits that are imposed by law.

In general the rule is that claims must be presented to the tribunal within three months of the act complained about. There are, however, some exceptions to this basic rule:

- ■ a claim for interim relief should be made within seven days of the dismissal;

- ■ a claim for a redundancy payment should be made within six months of the termination (although under section 164 Employment Rights Act 1996 the tribunal has a discretion to extend this by up to a further six months if it is just and equitable to do so in the circumstances);

- ■ a claim concerning a dismissal because of official industrial action should be brought within six months of the dismissal;

- ■ a claim against a trade union for unlawful exclusion or expulsion should be brought within six months of the unlawful act;

- ■ a claim for equal pay should either be brought during the employment or within six months of the termination of the contract of employment.

Time limits are mandatory and an employment tribunal has no jurisdiction to hear a claim that is brought out of time. In Rogers v Bodfari (Transport) Ltd [1973] IRLR 172 a claim for unfair dismissal was brought out of time but the tribunal actually held that the dismissal was unfair. The employer then raised the issue that the claim was brought out of time and that the tribunal therefore had no jurisdiction to hear the claim. The Employment Appeal Tribunal agreed that this was the case and has subsequently made the same point in Kudjodji v Lidl [2011] UKEAT/0054/11/CEA.

There are two limited circumstances where the time limit might be extended:

- ■ where it was not reasonably practicable to bring the claim in time;

- ■ where it is just and equitable for the limit to be extended.

Not reasonably practicable to bring the claim in time

In this instance the tribunal will have to consider the reasons why it was not reasonably practicable to submit the claim in time and determine whether these are sufficient to justify extending the limit.

It is inevitable also for the tribunal to determine whether a claimant acts reasonably in bringing his claim promptly once he knows of the time limit.

Just and equitable to extend the time limit

In some claims such as discrimination claims a tribunal might have more leeway to extend the time limit under the just and equitable head than it would on the basis of the not reasonably practicable test.

In Chohan v Derby Law Centre [2004] IRLR 685 the EAT identified that wrong advice by a legal adviser may also be sufficient to allow a tribunal to extend the time limit under the just and equitable reasoning, although a fault by a legal adviser in failing to lodge an appeal in the EAT on time is not generally grounds to exercise the discretion. In general solicitors and other legal advisers should be aware of all time limits and keep track of whether a claim is submitted in time. In Camden v Islington Community Services NHS Trust v Kennedy [1996] IRLR 381 the claim had to be made by 27 December. The solicitor posted the completed claim form on 19 December and should have received acknowledgement by 5 January but failed to check whether the claim was received until 30 January. It had not been received and the tribunal could not receive a later submission.

In the case of unfair dismissal claims time runs from the effective date of termination (ETD) so it is vital to know when this is:

- ■ If the dismissal is with notice then it is when the notice expires.

- ■ If it is without notice then it is the date on which the termination takes effect.

- ■ If it is a fixed or limited-term contract then it is the date on which the termination occurs.

3.2.2 Originating procedure (bringing a claim)

With some limited exceptions all claims should be submitted to the regional employment tribunal office on the appropriate form, the ET1. The claim should include a proscribed range of information:

- ■ the nature of the claim e.g. discrimination, unfair dismissal;

- ■ the claimant's personal details i.e. name and address;

- ■ details of any representation if appropriate;

- ■ the employer's details;

- ■ the details of the claimant's employment i.e. job description, length of service, hours of work, pay, etc.;

- ■ the details of the claim giving as much precise detail as possible;

- ■ the remedy sought (ordinarily this will be a form of compensation but it could involve other remedies such as for instance reinstatement or re-engagement in an unfair dismissal claim).

The form is reasonably easy to complete and there is extensive guidance on the website http://justice.gov.uk/forms/hmcts/employment.

The fact that some minor details are missing from the claim form will not necessarily prove fatal to the claim and prevent it from proceeding. However, it is possible for the tribunal secretary to refuse to accept the claim if some important detail is missing.

The Regional Tribunal Office checks the claim and allots it a case number and sends an acknowledgement of receipt to the claimant. It then sends a copy of the claim form and a response form (ET3) to the employer. Again guidance on completing the response form is available on the website http://justice.gov.uk/forms/hmcts/employment.

The employer is then bound to return the completed response form within twenty-eight days. If the employer is defending the claim then the response form should contain sufficient information to indicate the basis on which the claim is being resisted. If the employer fails to return the response form in time or has not been successful in gaining an extension to the time limit then a default judgment will be made. The employer could apply within fourteen days to have the default judgment set aside. If the completed response form has not been returned or it contains insufficient information then the tribunal secretary may refuse to accept it and may refer the matter to an employment judge who may then invite the parties to a pre-hearing review.

If both claim form and response form are appropriately completed then they are passed on to a conciliation officer. At the request of either party or on his own volition because he feels that it may be successful the conciliation officer will try to reach a settlement between the parties.

3.2.3 Conciliation, settlements and compromise arrangements

ACAS has a statutory duty to help parties to reach a voluntary settlement which would avoid the need for a tribunal hearing. It does this through the process of conciliation. A settlement that is reached through the conciliation officer could then be binding on the parties whereas in general an employee cannot waive his statutory rights so that a settlement between an employer and employee which does not involve the conciliation officer is not binding. Communications with the conciliation officer are not then admissible in the tribunal unless both parties consent.

There are two main ways in which a settlement can be reached without a tribunal hearing. The first of these is a settlement made on form COT3. This is a voluntary settlement reached with the conciliation officer. The settlement only applies to the matters that are identified in the COT3 so that a later claim on another ground is still possible. A claim is also possible where it is based on facts of which the employee was unaware at the time the settlement was made. Otherwise the settlement is binding on both parties.

The other type of settlement is a compromise agreement. This must:

- ■ be in writing;

- ■ relate to particular proceedings;

- ■ only occur after the employee has received independent legal advice either from a qualified lawyer or from a trade union official who is certified as being a competent adviser and in either case the adviser must have legal professional indemnity insurance;

- ■ identify who the adviser is;

- ■ state that the statutory conditions regulating the compromise agreement are satisfied.

Compromise agreements can be made in respect of most matters within the jurisdiction of employment tribunals, an exception being failure to consult with a trade union during a redundancy situation.

Compromise agreements only act as settlement of those disputes that have been raised when the agreement is reached but they are binding on both parties. Because compromise agreements amount to a contractual agreement connected with employment they can be enforced in a tribunal.

3.2.4 Case management

An employment judge has extensive case management powers by virtue of the Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2004 as amended. If a party fails to comply with a direction then the employment judge may make an order for costs or indeed may make an order to strike out all or part of either the claim or the response to it if the failure to comply with the direction means that a fair trial of the claim is then impossible.

The employment judge can use his powers to ensure that the case is dealt with as fairly and expeditiously as possible and that both parties are on an equal footing.

Either party can request further and better particulars or an order for discovery of documents. However, there is no automatic procedure for making such orders. The employment judge may make such an order only where the party requesting it would otherwise be unfairly prejudiced. Discovery cannot be used as a 'fishing expedition' or in other words as the means of establishing the existence of a claim. Where disclosure has been ordered the order continues right up to the end of the tribunal hearing.

Privilege from disclosure only applies to communication between clients and their professional legal advisers. If privilege is claimed then the potential injustice of nondisclosure must be balanced against what is in the public interest.

3.2.5 Pre-hearing review

The provision to hold a pre- hearing review was originally made in the Industrial Tribunal (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 1993 and is now in the Employment Tribunal (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2004 as amended.

The original purpose of the pre-hearing review was to assess whether either the claim or the response to it were unsustainable rather than this being discovered in the tribunal. At the pre- hearing review the employment judge may do a variety of things:

- ■ He can decide on preliminary matters and issue directions.

- ■ He can decide that, while a claim or the response to it is still arguable, it has little prospect of success, in which case he can order that party to pay a deposit (currently set at £500) in order to continue: if the deposit is then not paid within a set time the claim or response can be struck out.

- ■ He can decide that the claim or the response to it is so weak that it has no reasonable prospect of success, in which case he can stop it proceeding to the tribunal.

- ■ He can also strike out a claim or the response to it where it is vexatious, or where the manner in which it has been conducted is vexatious, or where there has been intentional and contumelious (meaning insulting) fault by the claimant, or where there has been such delay by the claimant that there is a substantial risk that a fair trial would not be possible.

Restricted reporting orders can also be made at the pre-hearing review. These are possible for example in discrimination cases where information of a personal nature might be revealed.

3.2.6 The procedure at the hearing

Employment tribunal hearings are public so the public and the press are entitled to attend, although restricted reporting orders can be made in certain cases. There are limited circumstances where a tribunal can sit in private:

- ■ where it would be against the interests of national security for the evidence to be heard in public;

- ■ where a person could not give evidence in public without breaching a statutory provision;

- ■ where the evidence had been communicated to the person in confidence;

- ■ where the evidence if given in public could cause substantial injury to the employer.

Some evidence may also be given in private to comply with Article 8 European Convention on Human Rights, the right to respect for private or family life.

A closed material procedure is also possible where the claimant and his representatives are excluded from part of the proceedings in the interests of national security. It has been identified in Home Office v Tariq [2011] UKSC 34 that this does not breach either EU law or the European Convention on Human Rights.

The composition of a tribunal panel is a legally qualified employment judge, a member drawn from a panel approved by the Secretary of State representing employers' associations and a member drawn from a panel approved by the Secretary of State representing a recognised trade union or other employee association. In unfair dismissal claims an employment judge sits alone.

The order of proceedings resembles court proceedings in many ways. However, the rules of evidence are different to those applied in courts and much more matters can be introduced.

Burden of proof also operates slightly different to it would in usual civil claims. In general the burden of proof does lie on the claimant who would therefore normally present his case first which can then be rebutted by the employer. In certain claims in employment tribunals, however, the burden is in effect reversed. In unfair dismissal claims if the dismissal is admitted it is then for the employer to establish the exact reason for the dismissal, that it fell within one of the five potentially fair reasons for dismissal and that it was also fair in fact falling within the reasonable range of responses test (see Chapter 22.5.1). Also under the Equality Act 2010 section 135 the burden of proof is also reversed in discrimination claims (see Chapter 15.1).

The role of the tribunal is to consider the facts, listen to the witnesses, study all of the evidence and then reach a decision on the basis of the relevant legal provisions. The duty of the tribunal is to apply the law as laid down by Parliament. In this respect the tribunal can take into account interpretations of law made by the EAT and the other superior courts. However, ultimately it is the statutory provision which must be followed.

In practice employment tribunals are bound to give a reasoned decision. They will usually give an oral decision in the hearing and then put it in writing at a later date. About 95 per cent of all decisions in employment tribunals are unanimous.

The employment tribunal will also provide the appropriate remedy. Financial remedies vary with the particular type of claim and there are also special rules for claims that are brought on the basis of EU law. Awards also attract interest on a daily basis until they are paid. In the case of unfair dismissal claims reinstatement and re- engagement are also possible remedies (see Chapter 22.7).

3.2.7 Appeals

An appeal from a decision of an employment tribunal is made to the Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT). The appeal must be made within forty-two days of the date when the written reasons for the decision was sent to the appellant. It is only in very rare and exceptional circumstances that the EAT will relax this rule and allow an extension.

Once the appeal is submitted there is a preliminary hearing/directions. An appeal can only be on a point of law so the appeal will only be allowed to proceed to the EAT if it can be shown that it is reasonably arguable that the tribunal made an error in law. If it can then directions are made to ensure that the appeal is determined efficiently and effectively. If there is no arguable point of law then the appeal is dismissed at this stage.

An appeal cannot be made on a point of law that was not raised in the tribunal unless it would be unjust to let the other party get away with a deception or unfair conduct; or there is a glaring injustice in not permitting an unrepresented party to rely on evidence that could have been given to the tribunal; or if it is of particular public importance for a legal point to be decided on.

For the appeal to succeed one of the following must apply:

- ■ The tribunal misdirected itself in law.

- ■ The tribunal entertained the wrong issue.

- ■ The tribunal misapprehended or misconstrued the evidence.

- ■ The tribunal took into account matters that were irrelevant to the decision.

- ■ The tribunal reached a decision which no reasonable tribunal properly directing itself in law could have reached.

The appellant should state in precise terms which point of law is being questioned. Merely stating in general terms for instance that there is a misdirection or an error in law is insufficient.

Any further appeals are to the Court of Appeal and then on to the Supreme Court. Where an issue of EU law is involved and would resolve the case a reference may be made at any stage to the ECJ if it is necessary.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn's Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapters 1 and 20.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition, Pearson, 2012, Chapter 1.