16

Health and safety law

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the non-delegable nature of the employer’s common law duty to his employees

- ■ Understand the different aspects of the common law duty

- ■ Understand the character and scope of the common law duty

- ■ Understand the available defences to the common law duty

- ■ Understand how the duty has developed in the case of stress at work, and harassment and bullying

- ■ Understand the basic statutory duties

- ■ Understand the development of the duty through EU law

- ■ Be able to critically analyse the area

- ■ Be able to apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

16.1 Introduction: the significance of health and safety at work

According to the Health and Safety Statistics 2011/12 published by the Health and Safety Executive, for the period 2011/12:

- ■ 1.1 million working people were suffering from a work-related illness;

- ■ 173 workers were killed at work;

- ■ 110,000 injuries were reported under RIDDOR (Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 1995);

- ■ 212,000 reportable injuries occurred (ones involving more than three days’ absence from work);

- ■ 27 million working days were lost due to work-related illness and workplace injury;

- ■ workplace injuries and ill health (excluding cancer) cost society an estimated £13.4 billion (in 2010/2011).

Besides these, closer examination of the statistics also reveals the following:

- ■ There were 1 million self- reported injuries at work in the period.

- ■ There were more than 12,000 work related deaths in the period (the largest cause being cancer and the second largest chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder).

- ■ There were over 8,000 deaths (over 5,000 from the construction industry) from work related cancer and 13,000 new cases estimated per year.

- ■ There were 261 occupational asthma cases seen by consultants in 2010, according to GPs there are about 7,000 new cases of work related respiratory disorders each year, and about 4,000 COPD deaths each year caused by past exposure to gases, dust and fumes at work.

- ■ There were 141,000 new cases of work related musculoskeletal disorders with 297,000 pre-existing cases and 7.5 million working days lost.

- ■ According to GPs there are about 40,000 new cases of work related skin diseases each year with nearly 1,500 dermatitis cases seen in 2010.

- ■ There are about 20,000 new cases of work related noise induced hearing loss each year.

- ■ There are about 1,500 new claims each year for Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit arising from hand–arm vibration disorders.

- ■ There were 221,000 new cases of work related stress and 10.4 million working days lost through work related stress.

By any standards the figures are staggering and indicate how significant the area of health and safety at work is and how important it is to ensure health and safety at work, not just because of the human cost to employees and their families but the cost to society as a whole.

This is not to say that these figures are at all comparable with the situation during and immediately following the Industrial Revolution and the desperate need for legislative intervention in the nineteenth century (see Chapter 1.3). However, while it has to be accepted that different types of work involve different dangers, it would nevertheless seem that any death at work or resulting from work ought to be considered unacceptable.

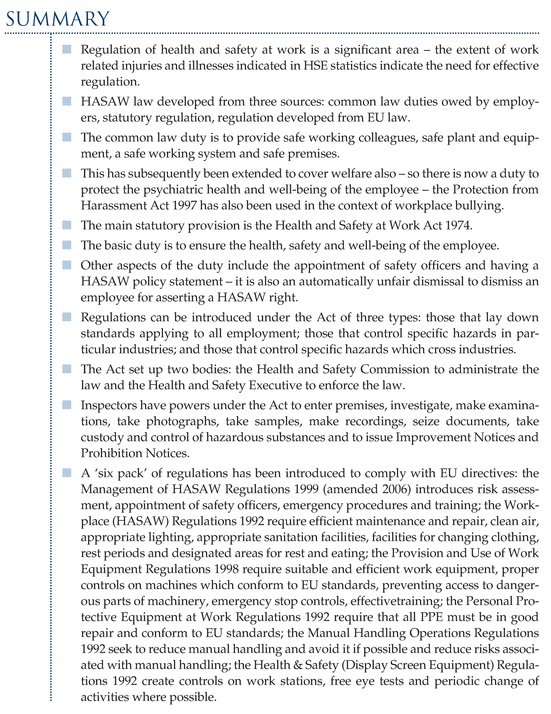

Regulation of health and safety at work involves both statutory provisions, some resulting from membership of the EU, but also common law.

16.2 Common law health and safety at work protections

16.2.1 The origins of liability and the non-delegable duty of care

Employers’ liability is a well developed principle that is to be found in both the common law and statute. It developed initially in the nineteenth century through very limited statutory controls following the Industrial Revolution. The very first industrial safety law was Sir Robert Peel’s Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 (see Chapter 1.3.1).

Most often those controls applied only to children and sometimes to women and were aimed more at regulating employment practices than at providing legal rights for employees. The first Acts to provide protection for adult male workers were the Factory Act 1833 (which created a Factory Inspectorate) and the Factory Act 1844 (which introduced the idea of fencing of dangerous machinery) (see Chapter 1.3.2).

So it took a long time for civil liability to develop in the area, not until the Workmen’s Compensation Act 1897, and workers rarely had the means of suing or gaining compensation for the injuries that they sustained through negligent practices (see Chapter 1.3.3).

The nature of the development has also meant that the area is quite complex and involves consideration of both common law and statutory provision.

Employment was traditionally seen, as it still is, as a contractual relationship, and so based on freedom of contract, and so originally no remedies were available in tort. Employees were free to negotiate their own contractual terms, at least in theory, and so if no reference to industrial safety was made in the contract then no civil action was available.

The original problems in bringing a claim

In the nineteenth century there were three further major barriers to workers’ claims in respect of injuries sustained at work:

- ■ the defence of volenti non fit injuria (voluntary acceptance of risk) – the worker in accepting the work was said also to have consented to the risks and dangers inherent in the specific type of work;

- ■ the defence of contributory negligence – this was a complete defence at that time so that if the employer could show that the employee was engaging in unsafe working practices then there could be no claim and this would be the case even though the worker had been directed to pursue those practices by the employer;

- ■ the so-called ‘fellow servant rule’ and the common law doctrine of common employment – where an employee was injured as the result of an unsafe practices of a fellow employee the employer could disclaim responsibility for that employee’s actions and there could be no claim against the employer, and there would be little point in claiming against the ‘fellow servant’ who would inevitably be a ‘man of straw’.

The effects of all of these have already been discussed in Chapter 1.4.5. Certainly industrial workers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries worked in very dangerous conditions and were given very little protection from the common law courts.

Development of limitations in the defences

The common law was generally hostile to workers and applied these three defences rigorously. Gradually, however, their severity was limited:

- ■ In Smith v Baker [1891] AC 325 the court accepted that volenti would only be available if the claimant freely accepted and understood the specific risk.

- ■ The Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945 altered the character of the defence of contributory negligence making it a partial defence only affecting the amount of damages to be received rather than removing liability altogether as had formerly been the case.

- ■ Finally in Groves v Lord Wimbourne [1898] 2 QB 402 the ‘fellow servant’ rule was held not to be available as a defence to a breach of a statutory duty; and in the Law Reform (Personal Injuries) Act 1948 the defence was finally abolished altogether.

Developments in industrial safety law

There were also further major positive developments in the law:

- ■ In Wilsons & Clyde Coal v English [1938] AC 57 the court identified that the employer owed a personal and non-delegable duty of care towards his employees.

- ■ Employers became liable for defective plant and equipment in the Employers Liability (Defective Equipment) Act 1969.

- ■ The principle of the employer insuring workers against injury that was introduced in the Workmen’s Compensation Act 1897 in respect of a limited range of named occupations was at a later stage extended to include all employees by the Employers’ Liability (Compulsory Insurance) Act 1969.

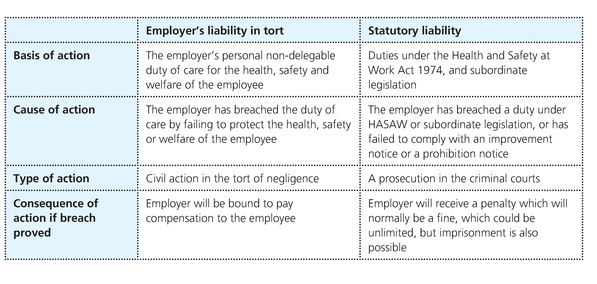

The main ways of imposing liability on an employer

Subsequent to all of these developments there are in principle three means by which an employee might impose liability on an employer:

- ■ for a breach of the employer’s personal non-delegable duty of care;

- ■ for a breach of a statutory duty e.g. under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 or other regulatory provisions where they include civil liability (see Chapter 16.3);

- ■ for the tortious acts of another employee through the principle of vicarious liability.

All three have been subject to significant development. Proving the complexity of the area, in a claim for an injury at work the pleadings will very often involve more than one, and there is the added further complication of being interspersed with a huge number of statutory duties and regulatory provisions, as well as regulations generated by the EU Framework Directive on Health and Safety 89/391 which may also provide civil liability actions.

All of these might prove beneficial to a claimant since commonly with statutory duties liability is strict or the burden of proof is reversed. Often also a common law duty is contained in any case within a statutory provision. For these reasons a claim is often a mixture of both, pleaded as alternatives. With statutory duties there is of course the added complication of demonstrating that the statute does indeed provide a civil remedy.

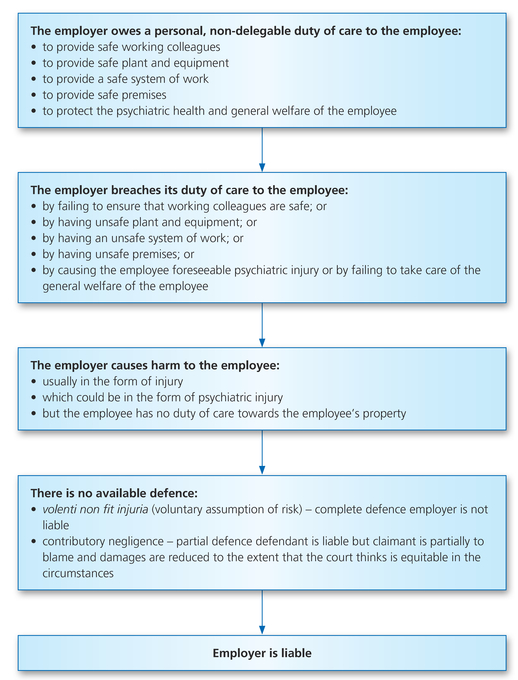

The basic duty and the employer's non-delegable duty of care

The basic common law duty in essence derives from the judgment of Lord Wright in Wilsons & Clyde Coal Co Ltd v English [1938] AC 57. The basic duty is to take reasonable care for the safety of all employees while acting in the course of their employment.

In fact we can separate out these three key aspects and add a fourth:

- ■ the duty to provide competent staff as working colleagues;

- ■ the duty to provide safe plant and equipment;

- ■ the duty to provide a safe system of work;

- ■ the duty to provide a safe place of work.

As the law has developed there has also now been established a general common law duty to protect the health and safety of the worker. This duty extends not only to physical health and well-being but in more recent times has also developed into an obligation to ensure the psychiatric health and well-being of the worker.

One significant fact that must be remembered is that these categories are quite simply stated and do not necessarily fully reflect the complexities of the modern workplace. In this sense the separate duties can quite easily overlap. In any case the likelihood is that a claim that an employer has breached his duties towards an employee will more than likely contain elements of more than one aspect of the duty. Besides this, as has already been indicated, there is likely to be overlap also with many of the statutory duties and, if there are civil remedies attached the claim, will possibly include a range of evidence of the employer’s breaches, both common law and statutory.

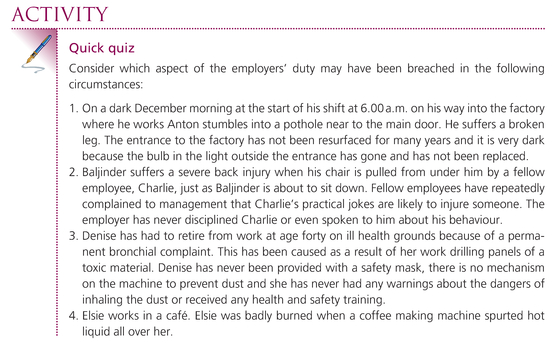

16.2.2 The duty to provide safe working colleagues

Most employees work within a team of some sort. Many employees work in conditions that include obvious dangers. The clear obligation on the employer is to ensure that all employees are competent to carry out the duties they are required to undertake in the course of their employment, and in that respect to protect their fellow employees.

Clearly the competence of a fellow employee will depend also on the extent of training given. The obligation on the employer is also then to train employees so as to avoid the risk of harm.

The employer is also bound to ensure the good behaviour of all employees while at work. As a result the employer should not tolerate any unsafe practices including practical jokes that might cause harm to other employees. The employer should deal with such unsafe practices effectively so that an employee who indulges in them should be disciplined and in extreme cases even dismissed.

Of course, as with any duty, the duty is based on reasonable foreseeability, so that an employer will not be liable if he is unaware or could not reasonably foresee that the employee causing damage or injury is likely to behave in the manner causing the harm.

In modern times actions using this basic common law duty are rare because of the principle of vicarious liability. However, it may still be useful when the employee’s act causing injury or damage falls outside the scope of employment.

16.2.3 The duty to provide safe plant and equipment

If the tools with which the employee works are not safe then he is clearly at risk of harm. The basic duty on plant and equipment then is that the employer must take reasonable care not only to provide safe plant and equipment but also of course to maintain it properly so that it remains safe.

As with safe working colleagues, training is a critical aspect of discharging the duty. The employer’s obligation then is not only to provide and maintain safe plant and equipment but also to train employees how to use equipment properly in order that it remains safe.

It may not be the fault of the employer that equipment is potentially hazardous. This could result from some defect in its manufacture. Nevertheless, where an employer is aware of defective equipment then it is part of his duty to remove it from use to do everything reasonable to avoid harm. A failure to do so may result in liability for injuries resulting from use of the defective equipment.

An employer can, however, always avoid liability if he is able to show that he has actually provided adequate equipment and that the injury has been caused because the employee has misused the equipment or failed to make proper use of it.

As with all aspects of the common law duty this aspect has been superseded by statute. Now the provisions of the Employer’s Liability (Defective Equipment) Act 1969 are a more likely source of liability. While the Act has a precise definition of equipment in section 1(3) ‘any plant and machinery, vehicle, aircraft and clothing’, it has still been subject to conflicting interpretation.

As with all statutory provisions the definitions within sections of Acts may be challenged and the court will be called on to interpret. This may lead to some surprising results.

16.2.4 The duty to provide a safe system of work

The duty to provide a safe system of work is all embracing and concerns all aspects of the work including use of equipment and of protective clothing as well as training and supervision. So it is very much about how the work is organised. There are clearly two key aspects to the duty:

- ■ the creation of a safe system from the outset;

- ■ a proper and continuous implementation of the system.

Creating a safe system

The general duty is to provide an effective system of work which is sufficient to meet any foreseeable dangers.

Implementing the system

The duty is not merely to create a safe system of work it is also ensuring that the system is carried out. A safe system is only safe if it is actually followed. Thus, for instance, there is no point in an employer possessing safety equipment if employees are not provided with it.

Many types of employment are dangerous and the nature of the work or by the people with whom the employee has to work creates a foreseeable risk of harm. The employer’s duty is to create a system that will help to avoid the risk of harm. A failure on the part of the employer to operate such a system may then lead to liability when an injury occurs.

In recent times it has been possible to bring action for the result of any physical danger in the workplace where the system of work is inadequate and as a result the employer has failed to protect the employee from foreseeable harm.

It is also insufficient for an employer to argue that he has created a safe system if the employees are unaware of it and therefore do not follow it. One aspect of this is that an employer might be liable for a failure to warn of the dangers associated with the work.

Many cases involve the provision and use of safety equipment. An employer will inevitably be liable for failing to provide such equipment where it is required. In Finch v Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Co Ltd [1949] 1 All ER 452 the employer did provide goggles but had not told the employee where they could be located and was then liable for the employee’s injury. It will also lead to liability if the employer fails to ensure that the safety equipment is used. In Qualcast (Wolverhampton) Ltd v Haynes [1959] AC 743 safety clothing was available but nothing done to ensure that it was worn but there was no liability because the injury was not sufficiently serious and besides this the risk was one that was obvious. It was the employee’s fault for failing to use the safety clothing. By contrast in Nolan v Dental Manufacturing Co Ltd [1958] when a chip flew off a grinding wheel an injury caused by not wearing safety goggles was of sufficient seriousness that there was liability.

Advances in modern technology and their effect on systems of work may also impact on working conditions. For instances the use of VDUs is commonplace. There is also a range of provisions under regulations on their use. The common law duty is that systems for using VDUs must not damage the health and safety of the employee.

It is not only contact with dangerous machinery or substances that carries with it a risk of harm. Contact with the public can also be stressful as well as present potential physical hazards to employees (see Cook v Bradford Community NHS Trust [2002] EWCA Civ 1616 and Ingram v Worcestershire County Council [2000] The Times 11 January 2000 above which both also illustrate this point). An employer might be expected to operate a system of work so that the employee’s safety is not unnecessarily threatened by public contact.

It is also the case that an employer cannot rely on unsafe practice using the argument that it is a common practice. Common practice may be an indication that a duty has not been breached but not if it is an inherently unsafe practice.

A more recent development of the employer’s duty of care to employees (see below 16.3.1) is the duty to ensure that the system of work does not cause undue stress to the employee.

However, it is also the case that employees owe a duty of care to themselves. In this respect an employee is expected to know of and guard against the risks associated with the job that they are doing.

Like the other aspects of the duty owed by employers to their employees, it is also true that the duty to provide a safe system of work has probably now been superseded by statutory provisions, for example by the duty to undertake risk assessment under the ‘six pack’ and other regulatory requirements on an employer (see 16.4.2).

16.2.5 The duty to provide a safe place of work

While this was not an aspect of the duty stated in Lord Wright’s judgment in Wilsons & Clyde Coal Co Ltd v English, it is nevertheless an obvious extension of those duties that premises should also be reasonably safe to work in. The general duty is to take all steps that are reasonably practicable in the circumstances to ensure that premises are safe.

It is obvious that in many instances industrial, and in some cases other premises, are potentially hazardous. An employer cannot guarantee safety and must only do what is reasonable to minimise the risk of harm. Where the employee exercises a particular skill or enjoys specific expertise liability may be avoided where the worker has failed to take account of his own safety. All employees exercising a skill should be aware of the risks associated with exercising the skill and guard against those risks themselves.

Many employees carry out their work away from their own work premises. A natural extension of the duty in such cases is that the duty extends to other premises on which they carry out their work.

Apart from the employer’s basic duty of care to his employees, an employer will often also own or rent and therefore be in control of the premises within which employees operate. As a result there can also be liability under the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957. As with other aspects of the common law duty the duty to provide safe premises has been superseded by statutory provisions, particularly those in the so- called ‘six pack’ of regulations.

16.2.6 The character of the duty

The duty, as already stated, is first and foremost entirely personal to the employer. It cannot be delegated to subordinate employees, however high ranking in the organisation. This means that liability cannot be avoided by claiming that it is the fault of another. It equally means that each and every employee is owed a duty of care.

Clearly also a higher standard of care is owed to inexperienced employees and an obligation to train sufficiently to do the job safely. A similar point applies in the case of employees who are more vulnerable. In James v Hepworth and Grandage Ltd [1968] 1 QB 94 the employee did put up warning signs but owed a greater duty of care to an employee who was unable to read. However, there was no liability since the employee had regularly observed fellow employees wearing the safety clothing. Similarly in Paris v Stepney Borough Council [1950] 1 KB 320 an employee who was already blind in one eye was caused complete blindness through an injury when safety goggles had not been provided. Although it was not commonplace for goggles to be used in the work, the employer should have realised that there was a greater risk of substantial harm in the circumstances.

The employer’s duty of care only extends to do what is reasonable in the circumstances. Particularly on industrial premises it would be an unreasonable burden to demand that an employee should guarantee the safety of employees and there is no obligation on the employer to go to extraordinary or excessively costly ends in order to avoid harm.

One possible argument that an employer might make in defence is that the injury was the result of a customary practice in the trade. It has been identified that, where injuries do occur during the carrying out of such a custom or practice, the employer can only escape liability if the practice itself is a reasonable one. Where practices are inherently dangerous the employer will be liable.

Accepting the fact that industrial premises inevitably present dangers, it is obvious that an employee might still be injured even though not actually engaged in work at the time. For this reason the law has sensibly concluded that the duty extends beyond the work itself to cover all ancillary activities which are reasonably associated with the work.

The employer is of course only obliged to guard against foreseeable risks and may take into account the practicability of any possible precautions in trying to avoid harm. There will, however, be liability if precautions taken to avoid a foreseeable risk are inadequate and increase the risk of harm.

While the duty is to do what is reasonable to avoid reasonably foreseeable harm, the extent to which an employer is liable may depend on what the judge considers should be foreseen. Two apparently conflicting cases illustrate this. In the first of these the court held that there was no liability since, applying the Wagon Mound test, the precise circumstances could not be foreseen.

By contrast in the second case the court took a more liberal view of foreseeability and accepted that neither the precise circumstances nor the precise damage need be foreseen as long as damage of the general kind in the general circumstances of the case could be foreseen.

As in other areas of tortious liability the ‘thin skull’ rule also applies so that the employer’s duty extends to considering the possible extent of the injury to the particular employee. Interestingly in such circumstances it is the former Re Polemis measure of remoteness of damage, that recovery of damages is possible for injury that is a natural and direct consequence of the breach, rather than the Wagon Mound, recovery only for foreseeable harm that is used.

The principle can also be seen in Smith v Leech Brain & Co. Ltd [1962] 2 QB 405 where an employee suffered a burnt lip as a result of being splashed by molten metal following his employers’ negligence. The burn activated a cancer from which the claimant later died. Since some form of harm was foreseeable, the court held that even though the death from cancer was not immediately foreseeable some harm was and the defendant was liable.

The duty is quite wide ranging but, while the duty protects the employee it does not extend as far as protecting his property.

16.2.7 Defences

An action for breach of the common law duty of care is essentially an action for negligence. As with all negligence claims there are a number of possible defences that can be argued by an employer. One very obvious way to defend a claim is by showing that there is in fact no negligence. We have already seen in Latimer v AEC (see 16.2.5 above) that, where the employer has done everything reasonably practicable to avoid the risk of harm the duty is not breached and there is no negligence. Similarly, if the harm suffered was solely caused by the employee’s fault then there is no breach of duty on the employer and no liability. In Brophy v Bradfield & Co Ltd [1955] 1 WLR 1148 an employee died when he was overcome by fumes in a boiler house. The employee was a driver, he had no reason to be in the boiler house and there was no reason why the employer would expect him to be there. The employer could not do anything to guard against the death and was not liable.

There are of course two defences which are always closely connected with negligence claims. They are inevitably defences that appear also very appropriate in the case of employer’s liability:

- ■ volenti non fit injuria (voluntary assumption of risk);

- ■ contributory negligence.

Volenti non fit injuria (voluntary assumption of risk)

Many if not most types of work carry with them their own specific risks and dangers. Certainly since the onset of the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of mechanised processes work became a more dangerous activity (see Chapter 1.2) and it was these increased dangers that ultimately led to the law intervening in and regulating industry (see Chapter 1.3).

The original argument raised by employers was that in accepting the work the employee also accepted the risks that went with it. However, even in the nineteenth century courts showed that they were reluctant to accept the absolute application of the defence of volenti in the context of employment (see Chapter 1.4.5).

Just because an employee works in a field that exposes him to some risk of harm does not mean that he automatically accepts the risk of harm. The three elements of the defence must still be satisfied:

- ■ The employee is aware of the precise risk of harm.

- ■ The employee is able to exercise free will.

- ■ The employee as a result voluntarily accepts the risk of harm in the circumstances in which he works.

The defence does then have some application where all three are satisfied and the employee fully understands the risks involved and his agreement to take the risk is free from any pressure by the employer.

Similarly where the employer by his negligence creates emergencies it is not then appropriate to try to apply the principles of volenti to the actions of those people responding to the emergency.

In general as a matter of policy the defence of volenti is unavailable where there is a breach of a statutory duty. However, in some limited circumstances it is possible to use the defence successfully. This could also be explained as the employee in effect being the sole cause of his injury.

Contributory negligence

Unlike volenti, which is a complete defence and thus absolves liability, contributory negligence is only a partial defence reducing the amount of damages but not absolving liability. We have of course seen that this was not always the case and thus with adverse consequences for employees (see Chapter 1.4.5).

The current basis for the defence is section 1 Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945.

There are two aspects to proving that the defence applies:

- ■ The employee failed to take care of his own safety.

- ■ This failure is partly the cause of the injury he suffers.

So the defence may be available where although an employer has breached a duty to his employee, the employee has also failed to take care of his own safety and as a result is partly responsible for his injury.

Where the court accepts that the employee has contributed to his own harm and that contributory negligence should apply then damages will be reduced by an amount considered just and equitable by the court according to the extent to which the employee did contribute to his own injury.

The defence may be available even in extreme situations. Thus where the death of an employee has resulted from negligence by the employer but it is accepted that the employee also contributed to his own harm by failing to take care of his own safety damages may be reduced even though the employer is still liable.

It has also been accepted, however, that employees may be treated more leniently by the courts when it comes to a finding of contributory negligence. In Caswell v Powell Duffryn Collieries [1940] AC 152 the court explained this approach. It is likely that the pressures of work mean that employees may take less than full care of themselves and their sense of danger dulled by familiarity, repetition, noise, confusion and fatigue. In such circumstances the court felt that employees should be protected from their own carelessness, particularly in the case of statutory regulations which are designed specifically to offer such protection and it would be to defeat the object of the provision to do otherwise.

One controversial issue concerns whether it is possible to impose liability on the employer at the same time as declaring 100 per cent contributory negligence on the part of the employee therefore leading to no award of damages.

The decision has been criticised by both judges and academic commentators.

In Pitts v Hunt [1930] 3 All ER 344, the Court of Appeal, reversing the High Court, had already stated that a finding of 100 per cent contributory negligence would be impermissible, and explained its decision on the basis that, under the Act, the claimant must suffer damage partly as a result of his own fault and partly as a result of the defendant’s fault, and 100 per cent contributory would indicate fault only on the part of the claimant.

The argument has subsequently continued. In Reeves v Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis [1999] UKHL 35; [2000] 1 AC 360 the trial judge held the deceased to be 100 per cent contributorily negligent. A majority of the Court of Appeal agreed but in the then House of Lords damages were reduced by 50 per cent, accepting that the claimant was only partially at fault. In Anderson v Newham College of Further Education [2003] ICR 212 the Court of Appeal suggested that Jayes was decided per incuriam and should not be followed. It is also possible of course to argue that all these commentators are missing the very special circumstances of Jayes, which, in the case of statutory duties might be repeated.

16.3 Developments in the duty of care

Over the years judges have developed the employer’s duty of care to his employees. They have done so by widening the boundaries of the duty to include other aspects and also by extending the range of injuries covered by the duty.

16.3.1 Stress at work and psychiatric injury

Certainly from the 1980s following mass unemployment and more competitive attitudes to work, stress at work has become a feature which is commonly referred to. Pressure in the workplace and excessive workloads led in the 1990s to the courts accepting work related psychiatric injury as actionable and to the introduction of a general duty to protect not only the health and safety of the employee but also his general well-being and mental health.

This led to a whole new field of law on stress related illnesses and psychiatric damage caused at work. The courts accepted that there is a general duty to protect both the psychiatric health and well-being of the employee where harm is foreseeable.

Work related stress has been defined as a harmful reaction that employees have to undue pressures and demands placed on them in their employment. The extent of the problem of work related mental illness is illustrated in the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) statistics.

The most recent estimates from its Labour Force Survey (LFS) showed that:

- ■ The total number of cases of stress in 2011/2012 was 428,000 out of a total of 1,073,000 for all work related illnesses.

- ■ The number of new cases of work related stress rose from 221,000 to 233,000 in 2010/2011 with 196,000 pre-existing cases (but the change is not statistically significant).

- ■ A total of 10.8 million working days were lost in the period through work related stress.

- ■ The industries that reported the highest rates of work related stress in the three years prior to the survey were health, social work, education and public administration.

- ■ The occupations that reported the highest rates of work related stress in the three years prior to the survey were health and social service managers, teachers and social welfare associate professionals.

The development of this aspect of the duty of care means that an employee is entitled to treat a psychiatric injury caused by negligent work practice in the same way that a physical injury would be dealt with. The courts have developed principles for establishing when the duty is breached.

Another context in which stress claims are also likely to occur is redeployment and changing job roles and the effect of these on involved employees. They are obviously stressful circumstances for any employee. If an employer during such processes fails to take care of the employee’s general health and welfare then liability is possible provided that the Walker test is satisfied.

The Walker test also applies in a relatively straightforward way to changes in working practices. Again the employer will be liable if it is aware of the employee’s susceptibility to stress related illness and falls below the standard of care that is appropriate to the duty by imposing stressful or unsafe working practices thereby worsening the employee’s condition.

In some cases courts applied a stricter standard indicating that a duty only arises when an ordinary bystander would foresee that the stress suffered is likely to be of such a degree as to cause a recognised psychiatric disorder.

In any case Walker criteria must be satisfied before a successful claim can be made. This means that it is for the claimant to show that it is the actions of the employer, knowing of the employee’s existing illness that has caused the later illness.

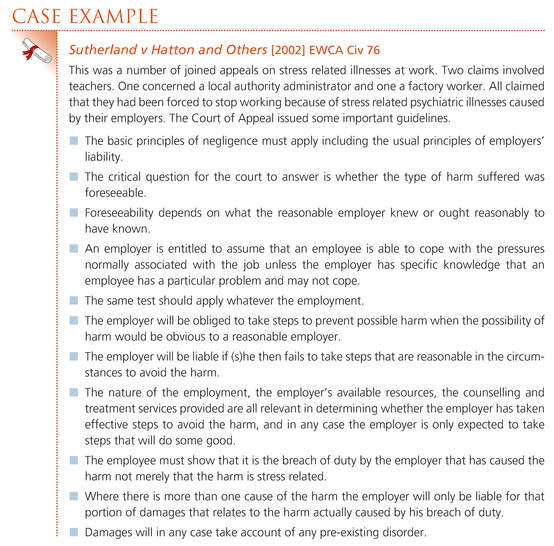

Because the area is a difficult one for judges to determine the Court of Appeal later produced guidelines for determining liability. These guidelines seem much stricter than the basic Walker test and appear to make it very difficult for claimants to bring successful claims for stress related psychiatric injuries.

He also comments on the judgment in Hatton: ‘With that guidance, courts are likely to be all the more willing to apportion and limit damages, to take account of the factors noted and if they do, the decision ... will mark a significant development in the law.’

The Court of Appeal has more recently re-emphasised the point that a successful claimant must show that it was reasonably foreseeable that (s)he would suffer a psychiatric illness as a result of the employer’s breach of duty, not just that (s)he would suffer from stress.

The House of Lords (now the Supreme Court) subsequently had the opportunity to review the principles laid down in Hatton.

Following Barber the Court of Appeal applied the Hatton criteria to individual cases in joined appeals, Hartman v South Essex Mental Health & Community Care NHS Trust, Best v Staffordshire University, Wheeldon v HSBC Bank Ltd, Green v Grimsby & Scunthorpe Newspapers Ltd, Moore v Welwyn Components Ltd, Melville v The Home Office [2005] EWCA Civ 06.

In a later case Daw v Intel Corporation (UK) Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 76 the Court of Appeal held that ‘indications of impending harm to health were plain enough for the [employer] to realise that immediate action was required’. The claimant had sent many notes to her employer drawing their attention to stress caused by overwork and confused lines of communication. The court also held that the mere fact of offering counselling was not sufficient to avoid liability.

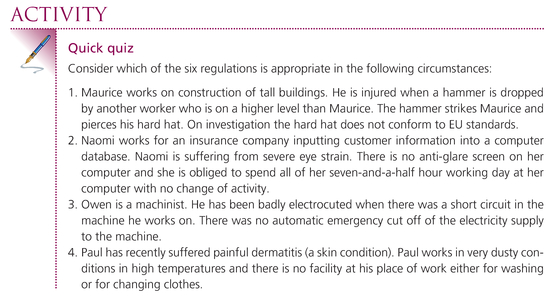

Figure 16.1 Diagram illustrating the employer’s common law liability for failures to take care of the health, safety and welfare of the employee

16.3.2 Bullying and the Protection from Harassment Act 1997

Quite obviously bullying and harassment in the workplace can also lead to psychiatric harm. As a result where the employer fails to deal with the bullying this can amount to a breach of its duty and lead on to liability.

An important development in this respect came when the courts showing willingness to impose vicarious liability where there is a breach of a statutory duty imposed on the individual employee rather than also on the employer. In this way a successful claim of vicarious liability can be made under s3 Protection from Harassment Act 1997.

There has been much recent case law with quite different results. The best publicised of these cases is Green.

However, in Merilie v Newcastle PCT [2006] EWHC 1433 a dentist failed in a claim for harassment against her former employers because she suffered a lifelong personality disorder making her evidence unreliable since it was based only on her own perceptions.

16.4 Statutory and EU health and safety protections

16.4.1 The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974

Introduction

The sheer volume of work related injuries and illnesses indicated in the introduction at the start of Chapter 16 demonstrates the need for effective regulation of health and safety at work. As we have seen in Chapter 1.4.5 the common law was originally unhelpful in respect of the safety of employees. Indeed by the restrictions placed on the tort the then House of Lords may have missed a great opportunity in the case of Rylands v Fletcher [1868] LR 1 Exch 265, LR 3 HL 330 to develop a general duty concerning responsibility for dangers which might have been very beneficial to employees in the changed conditions brought about by industrialisation. As a result legislation was always significant in developing regulation of health and safety at work from the very first Act, Peel’s Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 through to the very extensive Factories Act 1961 and Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963.

However, the defects in the law developed by successive Parliaments were obvious by the late 1960s and the Labour government in 1969 set up the Robens Committee to review the whole area of industrial safety. The committee’s Report was published in 1972. It identified a series of problems with the existing law:

- ■ It was cumbersome and therefore complex being contained in numerous different statutes.

- ■ It was made more complex because the various statutes often overlapped in their application.

- ■ In general the law focused on premises rather than employees.

- ■ As a result of this large numbers of workers were not covered by existing legislation.

- ■ Responsibility for health and safety was divided between too many different ministries and government departments.

- ■ The number of different inspectorates, seven, was excessive.

As a result the Committee suggested that there should be three separate levels of control of health and safety at work:

- ■ a broadly based general legislative framework;

- ■ made more specific through regulations and statutory codes of practice;

- ■ with the addition of voluntary codes in individual establishments.

The Act — general points

The Act, apart from placing all of the general legal obligations in a single enactment and answering the first criticism of the previous law, also made some fundamental changes to the way that health and safety at work is regulated. It applies to workers not to premises, covering all employees except domestic workers. As a result of this seven million employees who had previously had no protection came within the statutory protection. Subsequent legislation has extended this to trainees on government training schemes, certain offshore workers and police officers, and the Act now also covers many people who while not strictly employees may be affected by activities in workplaces.

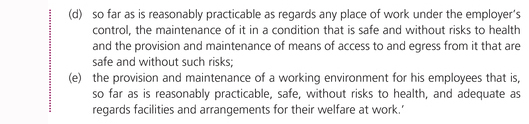

Like the common law the Act introduces a series of duties imposed on employers found in sections 2–9. Some duties are absolute; others depend on what is ‘reasonably practicable’. In contrast to the common law the Act is based on criminal sanctions for breaches. Section 47 identifies that no civil proceedings arise from the Act. Although of course under the Civil Evidence Act 1968 criminal conviction could be used as evidence in a civil action.

However, it also looks for cooperation with employers through voluntary codes.

The duties under the Act

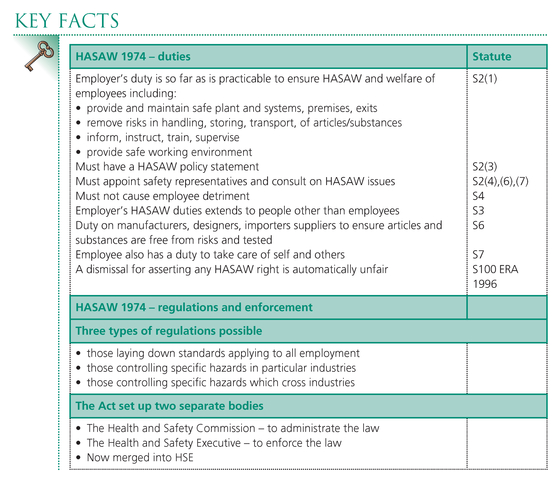

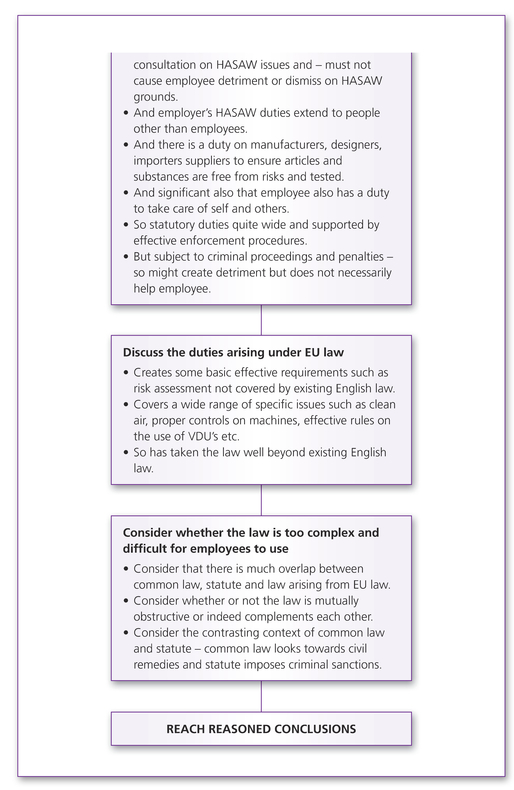

The basic duty is in section 2(1):

The duties all depend on what is ‘reasonably practicable’. This mirrors common law where the standard of care is that of the reasonable employer who is not bound to go to extraordinary lengths to guarantee safety but only to do what is reasonable in the circumstances.

Under section 2(3) the employer is bound to produce a written health and safety policy statement and to bring this to the attention of all employees. This must be updated as often as is needed for changes in the workplace. There is no statutory guidance on the contents of the statement so it is based on the individual needs of the workplace. Although there are some minimum contents, however, that a statement would need to cover and that could be gained from advice from the Health and Safety Executive. These would include:

- ■ the employer’s general health and safety policy;

- ■ the form and frequency of health and safety inspections;

- ■ the identity of persons responsible for health and safety and their individual responsibilities;

- ■ procedures for raising and dealing with health and safety issues;

- ■ procedures in the case of emergencies.

One major innovation of the Act appears in sections 2(4), 2(6) and 2(7). This is the duty to consult employees on health and safety matters and to appoint safety representatives for the purpose of consultation. Where there are recognised trade unions it would be common for the union to appoint or elect the representatives and the employer has a duty to consult with these safety representatives. Safety representatives will:

- ■ make regular inspections;

- ■ investigate health and safety risks and hazards;

- ■ investigate employees’ complaints and raise these with management;

- ■ represent employees in consultation with management and with HSE inspectors.

Under section 2(7) if two or more employees request it the employer should set up a safety committee. The employer must consult with the committee when introducing any new equipment or machinery and should also give full information on any health and safety hazards. Health and safety representatives are entitled to reasonable time off work for training and to fulfil their role.

Under section 3 the employer’s duty also extends to non-employees who may be affected by health and safety risks. This duty is also placed on the self-employed. This duty obviously covers any legitimate visitors to the employer’s premises. It might also include sub-contractors working on the employer’s premises.

Under section 4 there is a duty on anybody in control of premises, other than domestic premises, to ensure as far as is reasonably practicable against risks to health and safety in all access and exits to plant and premises to people who work on the premises.

Under section 6 there is a duty on manufacturers, designers, importers, and suppliers of articles or substances:

- ■ to ensure as far as is reasonably practicable that they are free from risks to health and safety;

- ■ to test such articles and substances and to provide necessary information on how they should be used.

Following on from these duties some further complimentary duties owed by the employer under the Employment Rights Act 1996 are worth noting:

- ■ under section 44 ERA 1996 there is a duty on the employer not to cause an employee a detriment for involvement in a legitimate health and safety activity;

- ■ under section 100 ERA 1996 there is a duty not to dismiss an employee for any reason associated with health and safety, which would rank as an automatically unfair dismissal.

The Act also places certain duties of employees and others:

- ■ under section 7 every employee is under a duty while at work to take reasonable care for his own health and safety and of others who may be affected by his acts or omissions at work, and to cooperate fully with his employer on all HASAW issues;

- ■ under section 8 all persons owe a duty not to intentionally or recklessly interfere with or misuse anything provided in the interest of health and safety at work.

These are important because the duty to take reasonable care for one’s own safety include using all protective equipment and properly following all health and safety procedures. This helps to ensure that the working environment is in fact safe and mirrors the similar duty under common law.

Introduction of regulations under section 15 and Schedule 3 of the Act

The Act replaced the old system of individual statutes and so it gives the Secretary of State the power to introduce regulations by statutory instrument and also Codes of Practice to advance health and safety at work.

Three types of regulations are possible:

- ■ those which lay down standards that apply generally to all employment;

- ■ those which control specific hazards in particular industries;

- ■ those which control specific hazards but ones which cross industries.

They are usually introduced in statutory instrument by Secretary of State following recommendations by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

Such regulations can as well as other things:

- ■ repeal or amend existing provisions;

- ■ grant authority to specific bodies to enforce statutory duties;

- ■ identify parties who may be subject to criminal sanctions;

- ■ grant exemptions.

Enforcement of the Act and related Regulations

The Act originally set up two separate bodies:

- ■ the Health and Safety Commission (HSC) with the responsibility of administration;

- ■ the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) with the responsibility of enforcing the law.

In practice the HSC commonly delegated its responsibilities to the HSE and in 2008 the two were merged into the HSE.

Enforcement of the duties in the Act is by Inspectors with wide powers.

- ■ They may enter premises (and may do so with the support of the police if necessary, or indeed can be accompanied by other authorised persons).

- ■ They may investigate health and safety risks, carry out examinations, take photographs, take samples, make recordings, seize documents, take custody and control of hazardous substances or situations.

- ■ They may require relevant parties to answer questions.

- ■ They may use any other power necessary to carry out their duties.

Under section 21 Inspectors may issue Improvement Notices where any health and safety provisions have been contravened. These notices identify the provision which has been breached, indicate the improvement that is required and the period within which the improvement must occur.

Under section 22 Inspectors can also issue Prohibition Notices where a breach of a provision involves a risk of personal injury. The notice prohibits that activity until the risk has been removed.

Employers can appeal against either type of notice.

A further power under section 25 gives inspectors the power to take whatever action is necessary in a situation of imminent danger. Under section 42 the courts can order an employer to take steps to eliminate risks and can also impose fines.

16.4.2 The 'six pack' of regulations

Introduction

The European Union is a major provider of HASAW law originally through Article 118A, which was inserted into the EC Treaty by the Single European Act 1986 and later became Article 137 following the Amsterdam Treaty. The Article gave power to issue Directives in furtherance of HASAW by a qualified majority voting system. This is now covered by Article 153 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

A number of directives have been issued. Probably the most significant is the so-called ‘six- pack’ introduced in 1992 but subsequently amended. One of the most significant aspects of the directives is the requirement for proactive steps to be taken, for example risk assessments, as well as provision of information and training. They have all been implemented in the UK through statutory instruments.

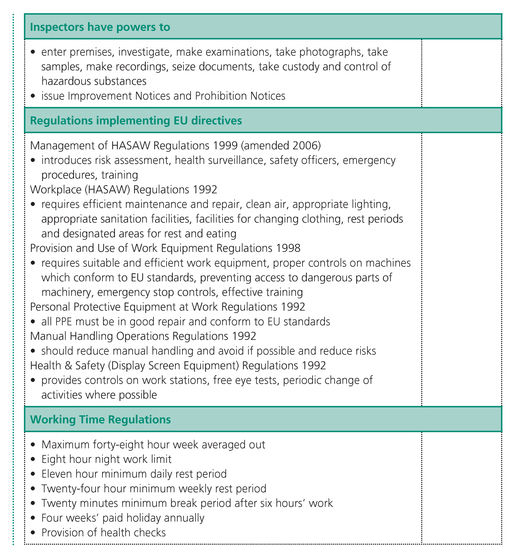

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 (amended 2006)

The regulations introduced the basic requirement of risk assessment, that employers must make ‘suitable and efficient assessments of the dangers facing their employees and anyone else likely to be affected by their work’. Risk assessment should cover everything in the work environment that is likely to cause harm. Procedures can then be put in place to deal with these risks and prevent harm. Risk assessments should be carried out regularly. Other than for small employers the results of risk assessments should be recorded in writing.

The regulations also require the appointment of safety officers and the establishment of emergency procedures. Employees should be fully aware of these procedures and be able to leave work and go to a place of safety in the event of an immediate danger in the workplace.

Employers must ensure that all employees are capable of doing the work safely and must provide the necessary training and information. Training should be carried out when an employee first joins but also at all points when the equipment or the work has changed.

Employees are under a duty to comply with all procedures and training given and to report to safety officers or the employer all dangers in the workplace and any failings in health and safety arrangements.

Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992

These regulations develop duties already in place in the 1974 Act. They involve the environment in which employees work and seek not only to make this a safe and healthy environment but also to ensure the provision of adequate welfare facilities.

There are various aspects to this:

- ■ There should be efficient maintenance, repair and cleaning of the work environment.

- ■ There should be sufficient fresh or purified air.

- ■ Temperatures should be reasonable and any source of heating premises should not produce any fumes that could be harmful to the employees.

- ■ There should be adequate lighting which is suitable for the activities being carried out.

- ■ There should be adequate floor space and all travel routes through the workplace should be adequate and suitable.

- ■ If it is possible for the work to be carried out while seated then suitable seats should be provided.

- ■ Doors, windows, gates, staircases, escalators etc. should all be safe.

- ■ There should be provision of adequate sanitary arrangements including both toilet and washing facilities.

- ■ There should be drinking water available.

- ■ There should be provision for changing clothes where necessary.

- ■ There should also be provision for rest breaks and eating and a designated suitable area for this.

Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998

These regulations seek to ensure that all machinery and other work equipment is safe and also used safely. The regulations require that all such equipment must be suitable for its use, it must be properly maintained and kept in good repair, and it must conform to EU requirements.

Besides this effective steps must be taken to prevent access to dangerous parts of machinery. Controls, including starting and stopping controls as well as emergency stopping controls should be provided and clearly marked with adequate warnings, and there should be provision for immediate isolation from power sources. All maintenance of machinery must be carried out with the machine switched off.

As with all the regulations, employees must be given appropriate information and be adequately trained in the use of equipment.

Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations 1992

Personal Protection Equipment is defined in the regulations as: ‘all equipment (including clothing affording protection against the weather) which is intended to be worn or held by a person at work, and which protects him against one or more risks to his health and safety’.

The regulations seek to ensure that all such equipment is indeed safe to use. On this basis all such equipment must conform to EU standards or it is considered unsuitable.

There are some fairly obvious examples including helmets, gloves, goggles, hard hats, harnesses, safety footwear, high visibility clothes.

The main provisions are:

- ■ There should be an assessment of suitability of the equipment.

- ■ All such equipment must be compatible with any other used.

- ■ It should be kept in good repair, cleaned or replaced regularly as appropriate.

- ■ Employees must be given full information regarding risks.

- ■ Employees must be trained in the use of the equipment.

- ■ The employer must ensure that it is used properly.

Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992

These regulations cover any form of manual lifting in the workplace, including lifting objects, putting them down, pushing them, pulling them or any other form of carrying or movement by hand. The main obligation on the employer is, as far as is reasonably practicable, to avoid any form of manual lifting. The HSE identify that as many as one-third of back injuries lasting more than three days result from manual lifting.

If it is impossible to avoid manual lifting then a risk assessment should be carried out in order to do everything possible to minimise the risk of injury through manual lifting. In particular the employer should reduce the risk of injury by considering the size, shape and location of objects that require manual lifting.

Schedule 1 of the Regulations contains a lengthy list of questions that an employer should check in order to reduce the risk of injury.

The employer is also obliged to provide employees required to engage in manual lifting with full details of the risk.

Health & Safety (Display Screen Equipment) Regulations 1992

The regulations deal with work with computers and other display screens, which has become a big feature of many areas of work, quite apart from there being certain jobs such as data entry which are completely involved with using such screens. Inevitably there are many health problems such as eye strain and muscular strain that can result from using display screens for long periods. Health problems appear to arise from poor equipment, poor environment and poor posture, so the regulations seek to cover all of these.

Employers are obliged to analyse all workstations to assess HASAW risks to employees, and there is an inevitable duty on employers to reduce such risks.

The main provisions are:

- ■ VDUs must not flicker, should be free from glare, and must swivel and tilt.

- ■ Keyboards must tilt and must be free from glare and the workspace in front of keyboards must be sufficient for the employee to rest his arms comfortably.

- ■ Desks must also be free from glare, and there must be enough space on desks to allow flexible arrangement of other equipment and documents.

- ■ Seats must be adjustable in height, and the back in height and angle, and footrests should be available if requested.

- ■ There must be appropriate contrast in lighting between the screen and its background, and windows should have blinds.

- ■ Heat and humidity levels should be adequate and not uncomfortable.

- ■ Radiation must be negligible.

- ■ There should be regular breaks or changes of activity from working with the VDU.

- ■ Employers must offer free eyesight testing at regular intervals and provide special glasses for screen work if necessary.

- ■ Employees should be consulted about health and safety measures and should be trained in the use of equipment.

16.4.3 The Working Time regulations

The regulations emanate from EU law and implement the provisions of the Working Time Directive 93/104 and the Young Workers Directive 94/33. They were only implemented after a change of government, and the previous government’s failure in an action in the ECJ. It had argued that the directive was social policy for which the UK had an opt out. In fact the directive was introduced as health and safety law.

The directive was updated in the Working Time Directive 2003/88. As well as the basic protections, this provides special rules for working time in certain specific sectors such as doctors in training, offshore workers, sea fishing workers, workers in urban passenger transport and in other specific transport sectors. The EU Commission has in fact initiated a series of consultations reviewing how working time arrangements operate in different Member States and drafted a proposal in 2009 for further amendment to the directive. However, the Commission and the European Parliament could not agree on the proposal and so it has not progressed.

The directive introduced a set of minimum rules to protect the health and safety of workers in all Member States. Every worker is entitled to:

- ■ a limit to weekly working time, which must not exceed forty-eight hours on average, including any overtime;

- ■ a minimum daily rest period, of eleven consecutive hours in every twenty-four;

- ■ a rest break during working time, if the worker is on duty for longer than six hours;

- ■ a minimum weekly rest period of twenty- four uninterrupted hours for each seven day period, which is added to the eleven hours’ daily rest;

- ■ paid annual leave, of at least four weeks per year;

- ■ extra protection in the case of night work (for example, average working hours must not exceed eight hours per twenty-four hour period; night workers must not perform heavy or dangerous work for longer than eight hours in any twenty-four hour period; there should be a right to free health assessments and in certain situations, to transfer to day work).

The Regulations make the following provisions:

Maximum weekly working time

Under Regulation 4 this must be no more than forty-eight hours per week averaged out over a seventeen-week period (although in certain circumstances the period can be longer). Under Regulation 5 the worker can also agree in writing to work longer than forty- eight hours. The average of forty-eight hours has to be calculated in a way which takes into account periods of leave, sickness and other periods which would normally occur. For example, a worker cannot be asked to work excess hours to make up for periods of holiday taken.

Working hours include any time when the worker is at the employer’s disposal and is expected to carry out activities for the employer. So it can include:

- ■ work related training is counted as part of the working week;

- ■ being on call.

But it will not generally include:

- ■ travel time to and from work;

- ■ lunch breaks (except for working lunches).

Minimum rest periods

Under Regulation 10 the minimum daily rest period is an uninterrupted eleven consecutive hours for an adult worker and twelve for a young worker.

Under Regulation 12 the minimum daily rest break period is twenty minutes after six hours of work (although in special circumstances these periods can be accumulated) or thirty minutes for young workers. Rest breaks should be uninterrupted and spent away from the work station. There is also a provision for adequate rest breaks where the monotony of the work would put the worker’s health at risk (although there is no definition of ‘adequate’).

Under Regulation 11 the minimum weekly rest period is an uninterrupted period of twenty-four hours in each seven day period (although this can be converted to two days off in each two week period and in special circumstances days off can be accumulated and taken off later). In the case of a young worker the period of interrupted rest is forty-eight hours in each seven-day period.

Paid annual leave

Under Regulation 13, as amended in the Working Time (Amendment) Regulations 2007, since April 2009 the minimum paid holiday leave entitlement is 5.6 weeks or twenty-eight days (worked out pro rata for part-time workers). It is not possible to replace holiday entitlement with payment in lieu except where service comes to an end. Nor can payment in lieu be made for any statutory holiday entitlement. It is also no longer possible to pay ‘rolled up’ holiday pay (in other words weekly pay which includes a payment for holiday pay). This is because holiday payment should be made at the time the holiday is taken. Workers are entitled to take leave from the commencement of their employment. Holiday entitlement should accrue on the basis of the number of working days in the year.

Night work

Under Regulation 6 night working is also regulated. Night work should not exceed eight hours in any twenty-four hour period aggregated over seventeen weeks. Night time for the purposes of the regulations is a period of seven hours including the period from midnight to 5.00 a.m. Night workers whose work includes special hazards e.g. steel workers should not exceed eight hours’ work in any twenty-four hour period (although there are exemptions in healthcare work). Night workers are entitled to a health assessment before being asked to work nights. Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds should not normally be expected to work nights.

A number of different classes of worker are excluded from the Regulations. These include under Regulation 18 people working on sea- going vessels who have their own provisions. It also under Regulation 19 includes domestic servants working in a private household. Regulation 20 covers people such as managing executives and people carrying out religious ceremonies where it would be difficult to measure times precisely. A variety of situations are also covered by Regulation 21 for instance where the employee’s work and residence are distant from one another, where the work involves security or surveillance, or care, works at docks or airports, broadcasting, public utility services, research and development, and also work that cannot be interrupted for technical reasons. Besides this exclusion from the Regulations can also result from a collective agreement under Regulation 23.

Further reading

Duddington, John, Employment Law 2nd edition. Pearson, 2007, Chapter 8.

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 11.

Nairns, Janice, Employment Law for Business Students 4th edition, Longman, 2006, Chapter 9.

Willey, Brian, Employment Law in Context 3rd edition. Pearson, 2009, Chapters 10 and 12.