22

Termination of employment (4) unfair dismissal

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the basis behind unfair dismissal

- ■ Understand who will be eligible for unfair dismissal purposes and who is excluded

- ■ Understand the situations when a dismissal is automatically unfair

- ■ Understand the potentially fair reasons for dismissing an employee

- ■ Understand what is meant by and the significance of the term ‘the band of reasonable responses’

- ■ Understand the significance of the ACAS Code and the requirements of compliance with procedural guidelines

- ■ Understand how the remedy afforded to a successful applicant will be determined

- ■ Understand the considerations that determine the amount of any compensation awarded and in what circumstances a tribunal may choose to limit or reduce the basic or compensatory award made to a successful applicant

- ■ Understand what the time limit is for submitting a claim and when that time limit will be relaxed

- ■ Critically analyse the area of unfair dismissal

- ■ Apply the unfair dismissal checklist to factual situations in order to determine whether a claim for unfair dismissal may succeed

22.1 The origins, aims and character of unfair dismissal law

Prior to 1971 the only real course to an employee who had been dismissed if he wished to challenge it was through the old common law action of wrongful dismissal (see Chapter 21). In effect the employer could dismiss an employee for no reason. The law on dismissals at that time reflected the old ‘master and servant’ rules (see Chapter 1.4.1) and the action for wrongful dismissal provided no possibility of enquiring into the fairness of the dismissal. Wrongful dismissal was based purely on form rather than fairness, whether the employer had dismissed the employee without giving the appropriate notice under the contract or by dismissing him he had prevented him from completing the remainder of a fixed-term contract. Inevitably the remedy for wrongful dismissal was very limited also since it only related to the breach of contract so damages would be restricted to the amount that should have been paid during the notice period. For most employees this would be a small sum only.

Unfair dismissal is a concept that was created in the Industrial Relations Act 1971. This Act was later repealed since it had more to do with the statutory regulation of industrial relations, and had its own court for enforcement. However, the provisions on unfair dismissal were later also inserted in the Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act 1978, and later still in the Employment Rights Act 1996 (as amended).

The original purpose of the rules on unfair dismissal was to detail in statutory form the situations in which a dismissal could be classed as unfair and therefore meriting a remedy, and in turn to discourage unfair dismissals.

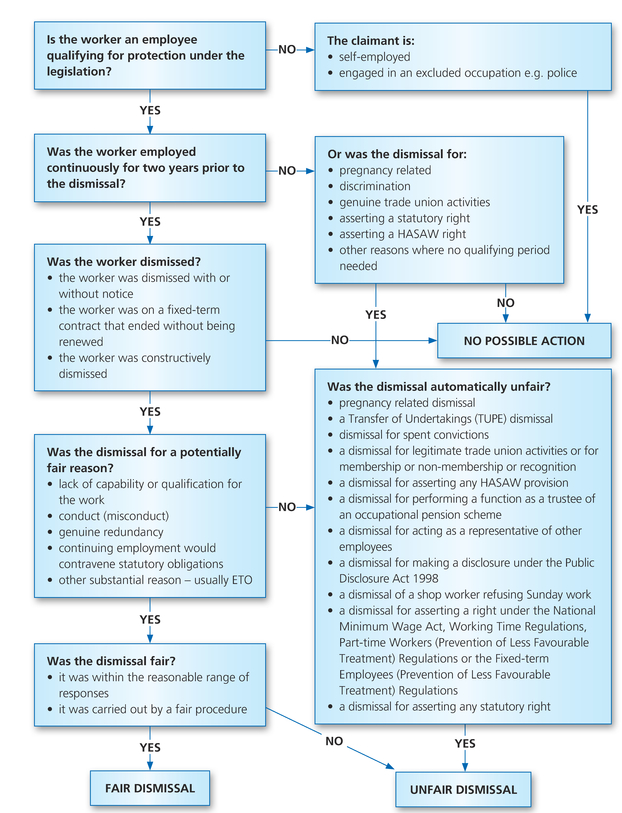

There are a number of key aspects to a claim for unfair dismissal which must be demonstrated:

- ■ The person claiming unfair dismissal must be an employee.

- ■ There must have been a dismissal (which is defined in the Act).

- ■ The person claiming must be eligible (which includes the appropriate period of continuous employment – although there are exceptions where continuity is not required).

- ■ It must be decided whether the dismissal is one which is identified as an automatically unfair dismissal.

- ■ If not it must be decided if the dismissal is of a class which is considered potentially fair.

- ■ If the dismissal is for a potentially fair reason then it must be established that it was fair in fact according to the reasonable range of responses test.

- ■ It must then be considered whether the dismissal was carried out according to fair procedures following the ACAS Code.

- ■ Finally the appropriate remedy should be decided – if this is damages then the amount of the award should be calculated.

If employment status is a concern, the tests for establishing employee status are those that have been covered in Chapter 4.3.

As we have seen in Chapter 19.3.1 the only circumstances in which an employee is entitled to consider that he has been dismissed are the three identified in section 95(1) Employment Rights Act 1996.

These have been considered separately in Chapter 19 and a dismissal is clearly one of three things:

- ■ The employer actually dismisses the employee whether he gives him notice or not.

- ■ The employer fails to renew a contract that is limited.

- ■ The employee claims constructive dismissal – that is the employee actually resigns but because the employer has breached a fundamental term of the contract.

If there is a dismissal of an employee the next step is to establish that he is eligible to claim.

22.2 Eligibility

The basic right to a claim for unfair dismissal arises from the fundamental right in section 94 Employment Rights Act 1996.

The section refers to any employee so in order to bring a claim a person must first be able to class himself as an employee (see Chapter 4.3). However, there are also a number of classes of employee who are excluded from the provisions and therefore ineligible to make such a claim. These include:

- ■ share fishermen (these are the crew of fishing ships who take pay as a share of the profits from the catch);

- ■ members of the police force (by section 200 Employment Rights Act 1996);

- ■ agreed exemptions authorised by the Secretary of State, e.g. in collective agreements with trade unions operating in substitution of the statutory scheme;

- ■ where there is an agreement to place the dispute under arbitration instead of under a scheme prepared by ACAS;

- ■ employees engaged in industrial action, providing that all of the workers are dismissed and none is taken back within three months;

- ■ employees working under an illegal contract – the general rule is that the courts will not enforce an illegal contract. The issue is what effect this may have on a claim for unfair dismissal. In some situations the courts are prepared to overlook the illegality.

A similar position is taken where the illegality is not causally connected to the claim.

- ■ Traditionally employees reaching their normal retirement age under the contract of employment, or sixty-five if none exists, were also excluded from claiming (except where this would be discriminatory) – but from 1 October 2006 following the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations there are no such age limits to a claim.

Continuous service

There is also a limitation based on the employee having more than two years’ continuous service at the time of the dismissal without which an employee is not eligible to claim. This qualifying period has been variously as little as six months and as much as two years. The current government returned the period to two years from April 2012.

The previous Labour government had returned the qualifying period from two years to one year. It seems therefore that there is a possible political motivation to the qualifying period of continuous service. It would in any case be possible to argue that it is both unnecessary for employers and unfair to employees. An employer already has very broad grounds for dismissing an employee fairly (see Chapter 22.4). This includes the very broad ‘any other substantial reason’ which will often be an economic, technical or organisational reason. There seems to be little justification for the employer to have an extra period of two years where the employee can be dismissed with no reason. When considered against the relative insecurity of the employee who may have left a secure job and then has two years with no job security unless he is dismissed for an automatically unfair reason seems to make unfair dismissal a very limited employment protection.

It is interesting to note that if the decision in R v Secretary of State for Employment ex parte Seymour-Smith and Perez [2000] IRLR 263 had been different then the qualifying period would have had to be abandoned entirely. Women had complained that the period, which was two years at the time, discriminated against them because more women than men would fall within the period because of child care. The ECJ held that it was potentially discriminatory. The House of Lords accepted that the statistics showed a greater proportion of women would fall within the period but insufficient to amount to actual discrimination.

In the following instances the two year qualification period does not apply:

- ■ The dismissal is for legitimate trade union activities, for acting as an employee representative, or for membership or non-membership of a trade union.

- ■ The dismissal is for asserting any Health and Safety provision.

- ■ The dismissal is related to pregnancy, childbirth, maternity, maternity leave, parental leave or dependant care leave.

- ■ The dismissal is discriminatory.

- ■ The dismissal is of a protected shop worker or betting office worker refusing to work on a Sunday.

- ■ The dismissal is for a refusal to work hours in excess of those required under the Working Time Regulations.

- ■ The dismissal relates to performing functions as a trustee of a pension scheme.

- ■ The dismissal relates to making a protected disclosure (‘whistle blowing’) under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

- ■ The dismissal is for exercising a right under the National Minimum Wage Act 1998.

- ■ The dismissal is for exercising a right under the EU Works Council Directive.

- ■ The dismissal is for exercising a right under the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000 or the Fixed-term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002.

- ■ The dismissal relates to spent offences – where disclosure is not required after the prescribed period under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 (although there are exceptions in sensitive occupations).

- ■ Dismissals following TUPE transfers (under the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006 – which developed out of the original EU Acquired Rights Directive).

- ■ The dismissal relates to a demand for flexible working.

- ■ The dismissal amounts to an unfair selection for redundancy for any of the above reasons – guided by extensive rules.

- ■ The dismissal is on medical grounds (here the qualifying period is only one month – s108(2) ERA 1996).

- ■ The dismissal is for asserting a statutory right.

22.3 Dismissals classed as automatically unfair

Certain dismissals will always be regarded as unfair: these are referred to as automatically unfair dismissals. Generally if an employer dismisses an employee for asserting or trying to exercise one of their statutory employment rights then it will be regarded as an automatically unfairly dismissal.

Employees enjoy a variety of statutory rights which include:

- ■ The right to a written statement of employment particulars (the s1 statement or statutory statement (see Chapter 5).

- ■ The right to an itemised pay statement.

- ■ The right not to be subjected to unlawful deductions from wages.

- ■ The right to guarantee payments when work is not available.

- ■ The right to a minimum notice period if the contract is silent.

- ■ Rights to maternity, paternity or adoption leave, time off for antenatal care, parental leave and dependant care leave, as well as the right to request flexible working arrangements and for the request to be considered.

- ■ The right not to be discriminated against because of gender, race, disability, religion or belief, sexual orientation or age.

- ■ The right to time off for public duties (e.g. jury service).

- ■ The right to remuneration during suspension on medical grounds.

- ■ The right in shop or betting work not to have to work on a Sunday.

- ■ The right to ‘whistle blow’ (make a public interest disclosure).

A worker is allowed to assert all of these rights.

There are a number of situations where a dismissal will be regarded as automatically unfair.

A dismissal relating to trade union membership, non-membership or activities

Under section 152 of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 a dismissal for legitimate trade union membership, non-membership or activities is automatically unfair. Trade union membership and non-membership is a protectable right so an employee cannot be dismissed for membership of a union. In Discount Tobacco & Confectionary Ltd v Armitage [1995] ICR 431 a woman sought help from her union during a dispute over pay and conditions and was dismissed as a result. It was held that the reason for her dismissal was her trade union membership and so the dismissal was unfair automatically. It could include legitimate activities such as accompanying an employee at a disciplinary or grievance hearing. However, this would not include unofficial activities.

Dismissal during an industrial dispute

Under section 238A Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 certain industrial action is protected and a dismissal could be automatically unfair. A dismissal for taking part in unlawful industrial action could be fair as long as the employer treats all employees engaged in the industrial action the same. Otherwise where there is unequal treatment under sections 237–239 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 the dismissal would be automatically unfair.

A dismissal in connection with the statutory recognition or derecognition of a trade union

This is also under the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992.

Unfair selection for redundancy

Under section 105 Employment Rights Act 1996 an unfair selection for redundancy is an automatically unfair dismissal.

A dismissal on a Transfer of Undertakings

Where an employee is protected under TUPE (see Chapter 18) and is dismissed by either the old or the new employer because of the transfer, or a reason connected with it, then the dismissal will be automatically unfair. In Litster v Forth Dry Dock & Engineering Co Ltd [1990] 1 AC 546 the liquidator of an insolvent business dismissed the workforce one hour before he sold it. The dismissals were held to be unfair and the liability to pay incurred by the liquidator was passed on to the new owner. The only exception to this would be if either employer could show that the dismissal was for an economic, technical or organisational reason. In Meikle v McPhail [1983] IRLR 351 a pub was taken over and the new owner decided that major economic savings were essential and dismissed a barmaid. The dismissal was held to be an ETO reason and necessary and fair in the circumstances so the dismissal was fair.

Dismissal on the grounds of pregnancy or maternity or parental rights

Under section 98 Employment Rights Act 1996 a dismissal for any reason connected to pregnancy is automatically unfair. This could include any reason connected with the employee’s pregnancy, a dismissal during the ordinary or additional maternity leave, because the employee has taken, or wants to take, ordinary or additional maternity leave, or dismissal resulting from a suspension from work because of health and safety, or if the employee returned back to work late from maternity leave because the employer did not properly tell the employee when the leave ended, or gave the employee less than twenty-eight days’ notice of the end date of the maternity leave and it was not practical for the employee to return to work.

Also covered is adoption leave, parental leave, paternity leave, time off to look after dependants. These are all under separate Regulations (see Chapter 8.5).

A dismissal in connection with a request for a flexible working arrangement

This falls under section 104C Employment Rights Act 1996.

A dismissal for any Health and Safety at Work related reason

Under Section 100 Employment Rights Act 1996 any dismissal for a reason related to health and safety is automatically unfair. This could include:

- ■ carrying out activities in the role of health and safety representative to reduce risks to health and safety;

- ■ performing or trying to perform duties as an official or employer-recognised health and safety representative or committee member;

- ■ bringing a concern about health or safety in the workplace to the employer’s attention;

- ■ leaving, proposing to leave or refusing to return to the workplace (or any dangerous part of it) where there is a serious and imminent danger which cannot be prevented;

- ■ the employee taking or trying to take the appropriate steps to protect himself or other people from a serious and imminent danger;

- ■ it also includes where the employee has refused an order that would put himself, fellow workers and other persons at risk.

A dismissal for exercising a right under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998

This is sometimes referred to as ‘whistle blowing’ and a dismissal because of this would be automatically unfair under section 103A Employment Rights Act 1996.

A dismissal that is discriminatory

This includes discrimination on gender, race, disability and more recently on sexual orientation, gender reassignment, religion or belief and age.

A dismissal of certain protected shop workers for refusal to work on Sundays

This falls under section 101 Employment Rights Act 1996.

A dismissal following the exercise of a right under the National Minimum Wage Act 1998

This falls under section 104A Employment Rights Act 1996. It could cover:

- ■ a dismissal because the employee is qualifying, or is about to qualify, to be paid the National Minimum Wage;

- ■ a dismissal because the employee is insisting on the right to be paid at least the National Minimum Wage;

- ■ a dismissal because the employee reports the employer for not paying the National Minimum Wage.

A dismissal relating to the Working Time Regulations

This falls under section 101A Employment Rights Act 1996. The dismissal might result from the employee refusing to break his working time rights, or refusing to give up a working time right, or refusing to sign a workforce agreement that impacts upon working time rights.

A dismissal because the employee performs duties as a trustee of an occupational pension fund

An employee who is an occupational pension fund trustee has the right to reasonable paid time off for those duties. Dismissal for being a trustee of an occupational pension scheme is automatically unfair under section 102 Employment Rights Act 1996.

Dismissal relating to activities as an employee representative

Dismissal for being an employee representative falls under section 103 Employment Rights Act. An employee representative cannot be fairly dismissed for being an employee representative, or for carrying out duties as a European Works Council representative, or a member of a special negotiating body, or an information and consultation representative, or for consulting with the employer about redundancies or business transfers.

A dismissal for exercising rights under the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000

A part-time worker should not be treated less favourably than a full-time employee. So the part-time employee should have the same or equivalent employment rights and benefits. Under the Regulations being dismissed for being part time, making a complaint about being treated less favourably than a full-time employee or giving evidence in another part-time employee’s claim is automatically unfair.

A dismissal for exercising rights under the Fixed-term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002

A fixed-term employee should not be treated less favourably than a permanent employee. So the fixed-term employee should have the same or equivalent employment rights and benefits. Under the Regulations being dismissed for being part time, making a complaint about being treated less favourably than a permanent employee or giving evidence in another fixed-term employee’s claim is automatically unfair.

A dismissal relating to tax credits

Under section 104B Employment Rights Act 1996 a dismissal for taking action in respect of a tax credit is automatically unfair.

A dismissal in connection with disciplinary or grievance hearings

Under the Employment Relations Act 1999 an employee has the right to be accompanied by a trade union representative or a colleague to a disciplinary or grievance meeting. The employee could also reasonably postpone the hearing if the representative is unable to attend. A dismissal for trying to exercise these rights or for accompanying a colleague is automatically unfair.

A dismissal for asserting a statutory right

This falls under section 104 Employment Rights Act 1996.

22.4 Dismissals classed as potentially fair

The law sensibly recognises that an employer must have the right to dismiss employees in appropriate circumstances. Two points need to be made:

- ■ There are only a limited number of recognised reasons where the law accepts that an employer may need to dismiss employees and these are identified as potentially fair reasons for dismissal.

- ■ However, the fact that the dismissal can be categorised as potentially fair does not make it automatically fair, it has to be fair in fact so the employer will still need to justify the dismissal in law when a claim is made.

Once the employee has proved that the termination of the contract amounted to a dismissal and that he is eligible to pursue a claim the burden then shifts and it is for the employer to show:

- ■ what the actual reason for the dismissal was;

- ■ that the reason for the dismissal is one that the Employment Rights Act 1996 accepts as potentially fair, in other words it is a reason which is prima facie fair;

- ■ that it was fair in fact.

The potentially fair reasons for dismissal are all identified in section 98 Employment Rights Act 1996.

So there are in effect five reasons, although even within the broad categories they can be broken down into other sub-categories.

- ■ capability and qualifications;

- ■ misconduct;

- ■ a fair selection under a genuine redundancy scheme;

- ■ a dismissal because of a statutory restriction;

- ■ any other substantial reason (this is obviously the one which gives employers most flexibility to dismiss).

22.4.1 Capability and qualifications

Both capability and qualifications under section 98(2)(a) are defined later in section 98(3).

Capability

So capability falls into two main aspects:

- ■ skill and aptitude;

- ■ absence through ill health or other persistent absence.

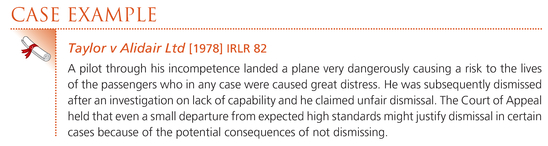

Skill and aptitude itself could divide into incompetence and neglect or poor performance. It is perfectly possible to dismiss on the basis of incompetence which would usually result from a series of incidents or poor performance. However, it could even involve summary dismissal for a single incident if the consequences of the incompetence are sufficiently serious.

What the employer should clearly do where there is an issue of incompetence or poor performance is to support the employee to improve performance and the employee should of course be aware that their performance is lacking. It is also difficult to successfully argue that an employee is incompetent if the employee has not been adequately trained how to do the work.

In reaching a decision to dismiss for lack of capability the employer should also have identified the employee’s incompetence and carried through every necessary procedural step. This could of course include warnings about performance. The ultimate question here is whether warnings did or would have made any difference to the employee’s performance. In Lowndes v Specialist Heavy Engineering Ltd [1976] IRLR 246 the employee was dismissed after making five very serious and very costly errors in his work. No warnings were given but the court still held that the dismissal was fair because it was felt that warnings would have made no difference in the circumstances.

The employer should obviously consider whether there are any alternatives to a dismissal. Ultimately, however, the employer is entitled to consider his business needs. Whether the dismissal is fair or unfair will depend on the individual circumstances in each case.

Ill health and absenteeism

Capability might also concern the health of the employee if that results in a continued inability to work. An employee is entitled to some sympathy and support from the employer during long term or regular sickness. However, it would be unfair on the employer to be expected to wait indefinitely for an employee to return from sickness absence. Lack of capability through illness is obviously closely connected with a termination of the contract for frustration (see Chapter 20.1). For a dismissal to be fair the employer obviously needs to consider all of the circumstances and the possible alternatives before dismissing.

While it is more likely to be seen as a fair dismissal where the employer has tried to support the employee and come up with alternatives, in Merseyside and North Wales Electricity Board v Taylor [1975] IRLR 60, however, it was held that there is no requirement on an employer to create a special job for an employee who has suffered sickness absence.

It is also of course not for the employer to presume that the employee is unfit to return to work by speculating on the possible risk of further illness.

In the case of persistent sickness absence the employer needs to ensure that the employee is aware of the need to improve the attendance record. For the dismissal to be fair the employer should carry out a proper system of warnings.

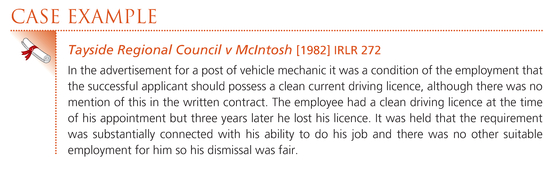

Qualifications

Qualification refers to any academic, technical or professional qualification relevant to the position held. This could relate to a formal qualification required in order to do the work.

Even though the qualification in question is not a formal contractual requirement it may still be seen as essential to the continued employment of the employee.

It is also possible that the qualification referred to is a specific aptitude requirement that is necessary for the work while not relating to a formal qualification. If the employee lacks the necessary aptitude and is dismissed as a result then the dismissal may be fair.

However, the qualification must represent a real need of the business. If it is not really related or a useful addition that the employer might like but is not necessary then the dismissal may well be unfair. In Woods v Olympic Aluminium Co [1975] IRLR 356 the employee was dismissed because he lacked management potential. His actual job was not dependent on this so the dismissal was unfair.

The employer must also be acting fairly in the dismissal. Even if the employee lacks the necessary qualification but there are other alternatives to dismissal then the employer should consider them.

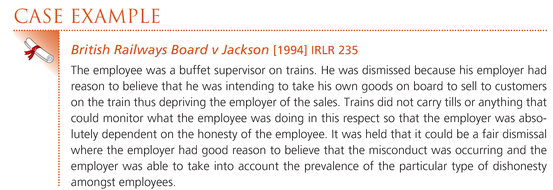

22.4.2 Misconduct

Misconduct is a legitimate reason for dismissal but the employers must follow their own disciplinary procedures or a dismissal may be unfair. Misconduct can arise as an issue both in terms of the employee’s misconduct during the employment but also from misconduct that occurs outside the employment if it is sufficiently serious to be relevant to the continued employment of the employee.

In the case of misconduct there may be a summary dismissal if there is sufficiently serious misconduct. Even where the misconduct is less serious for a dismissal to be fair it is vital that the employer has and follows its disciplinary procedures.

There are numerous reasons when misconduct might justify a dismissal. These can include refusal to obey lawful and reasonable orders, dishonesty, violent behaviour at work, intoxication at work. To dismiss fairly for misconduct then an employer must follow the correct procedure, their own procedure and must investigate fully and make full use of any system of warnings before dismissal.

Stock losses were also the cause of a dismissal in Whitbread & Co v Thomas [1988] IRLR 43. Here stock losses in an off- licence were recurring. This could have been either incompetence in failing to control the stock or could have raised questions about the honesty of the employee. Honesty is an essential aspect of much employment where the employee deals with the employer’s money or property. It can obviously lead to a fair dismissal.

Where a dismissal is for dishonesty then the employer must follow a proper investigation. The investigation should be measured against the proper legal test for dishonesty. Inevitably in different contexts what one employer concludes is dishonest may differ to another employer.

Any serious infringement of an employer’s disciplinary code might justify dismissal. It follows that if the employer is seeking to dismiss for gross misconduct then the disciplinary code should include the precise misconduct that the employer is intending to dismiss the employee for. In Dietman v London Borough of Brent [1988] IRLR 146 a clause in a contract defined gross misconduct for which summary dismissal was available. After an inquiry the employee was found to be grossly negligent in her duties. The court of appeal held that gross negligence did not fall under the employer’s contractual definition of gross misconduct so it concluded that the employee had been unfairly dismissed.

Violent behaviour is always likely to be misconduct that justifies dismissal. Indeed it is often included by employers in their works rules or disciplinary procedures as conduct justifying summary dismissal.

In Hussain v Elonex [1999] IRLR 420 an allegation of head butting a colleague was investigated and resulted in dismissal and this was held to be a fair dismissal. Fuller v Lloyds Bank plc [1991] involved an employee smashing a glass into a colleague’s face at the Christmas party. This was fully investigated by the employer before dismissing the employee and was held to be a fair dismissal.

A further issue is whether the employer is entitled to dismiss for misconduct that occurs outside work. In Lovie Ltd v Anderson [1999] IRLR 164 the employee was charged with indecent exposure. It was identified that the employer should still carry out a full investigation and allow the employee to state their case before any dismissal.

Dismissal for misconduct out of work probably depends on how much the misconduct could impact on the employment in question so it is very much an issue of context as the following cases show.

In contrast with the above cases the following cases were found differently.

22.4.3 Genuine redundancy

A genuine redundancy is also a prima facie fair reason for a dismissal. However, to be a fair dismissal it must also be a genuine redundancy situation. In Sanders v Ernest A. Neale Ltd [1974] IRLR 236 while there was a redundancy situation this was not the cause of the dismissal of the employees in question. In fact it was their refusal to work normally that had led to the redundancies.

It must also conform to all of the necessary procedural requirements – in Williams v Compare Maxim Ltd [1982] ICR 156 a test was established by the EAT: the selection criteria must be objectively justified and applied fairly, there must be proper individual and collective consultation, and the employer must have tried to find suitable alternative work for the redundant employees.

There must be objective criteria for selection and the person must be fairly selected according to that criteria. It is also vital that the employer should consult with the individuals affected and their representatives, although ultimately the employer should be looking for alternative ways of dealing with the problem. If a redundancy does not conform to these standards then it may well be unfair. There are extensive rules on redundancy in the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 (see Chapter 23).

22.4.4 A dismissal because of a statutory restriction

A dismissal because of a statutory restriction could arise because the business is prevented from operating by statute or other regulation for example in the case of a farm during a foot-and-mouth outbreak. It could also relate to the employment of people who are subject to immigration controls and have not been granted the right to remain under the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006.

Another way in which a statutory restriction might justify a dismissal would be where the employee originally did but now does not meet the statutory requirement. In Mathieson v W J Noble [1972] IRLR 76 (see 22.4.1 above) the dismissal was unfair because the employee was prepared to make his own arrangements during his driving ban at his own cost and the employer had not acted reasonably in failing to see whether the arrangement was satisfactory. In contrast in Appleyard v Smith (Hull) Ltd [1972] the dismissal of a mechanic required to have a clean current driving licence and who was banned from driving was fair. The employer’s business was small, the employee needed to test drive vehicles that he had repaired and so had to be replaced. There was no alternative employment.

In each case the fact that there is a statutory restriction does not automatically make the dismissal fair. It still has to be fair in fact so the employer needs to take the appropriate steps to find suitable alternatives.

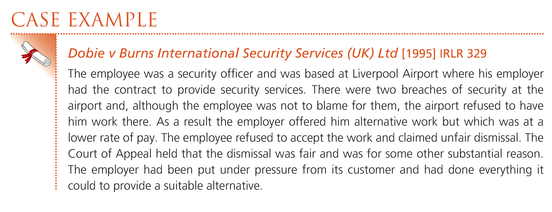

22.4.5 Other substantial reason

Dismissing for some other substantial reason is a kind of catch all category which gives the employer most flexibility to dismiss an employee.

In many instances a dismissal for some other substantial reason will in fact be as a result of the business needs of the employer. This is often referred to as an economic, technical or organisational (ETO) reason.

A lack of funding may well require a reduction in the conditions of employees and a refusal to accept this could lead to a fair dismissal under the category of some other substantial reason.

It is also possible that a dismissal for some other substantial reason could be where pressure is put on the employer to dismiss the employee. The pressure could come from important clients. In this instance the employer is not going to risk the business and so provided alternatives are considered the dismissal may be fair.

Where the employer dismisses because of pressure this could also be the result of pressure from fellow employees of the employee who is dismissed. Again if it is reasonable in the circumstances then it may be a fair dismissal for some other substantial reason.

However, there are equally situations in which courts will reject an employer’s submission that a dismissal was for some other substantial reason.

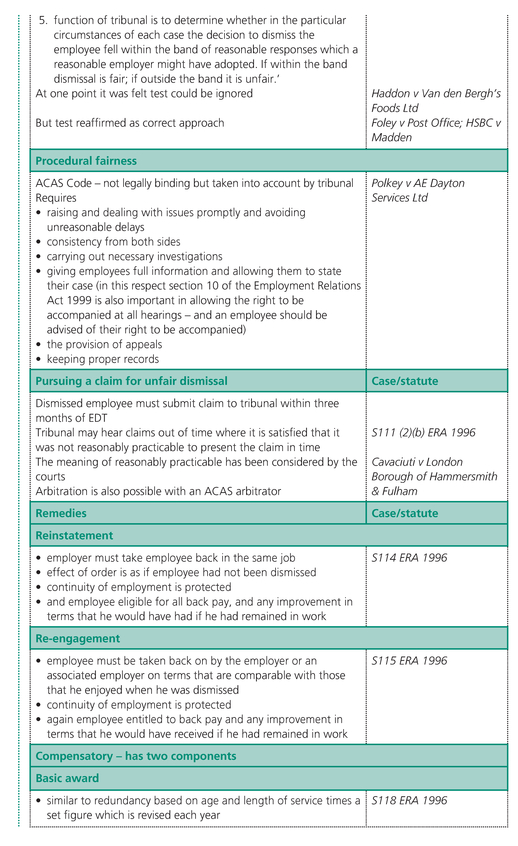

22.5 Determining whether the dismissal is fair

22.5.1 The reasonable range of responses test

Once it has been established that the dismissal came under one of the potentially fair heads of dismissal identified in section 98 Employment Rights Act 1996 then a tribunal must also determine whether the dismissal was fair in fact.

A tribunal can consider numerous factors in determining the fairness of a dismissal:

- ■ duty to consult the employee at all stages;

- ■ the existence and effect of any express or implied terms in the contract;

- ■ breaches of mutual trust and confidence;

- ■ introductions of new rules or procedures;

- ■ procedural faults;

- ■ instances of gross misconduct;

- ■ blanket dismissals;

- ■ selection criteria in redundancy;

- ■ breaches of the duty of fidelity;

- ■ internal hearings and appeals procedure;

- ■ the nature of sickness;

- ■ natural justice.

In essence the tribunal will use a statutory test to determine whether the dismissal is fair taking into account:

- ■ the circumstances of the case;

- ■ the behaviour of the employee;

- ■ the proper use of disciplinary and/or grievance procedures;

- ■ the consistency of treatment.

The test in section 98(4) Employment Rights Act 1996 is as follows:

Above all the employer should act reasonably in dismissing the employee. This principle derived originally from the case British Home Stores v Burchell [1980] ICR 303 which concluded that an employer should base a decision to dismiss on a genuine belief, based on reasonable grounds and following a reasonable investigation that there were grounds to justify the dismissal. This has become known as ‘the range of reasonable responses test’.

The test was later approved and explained in greater detail by the Employment Appeal Tribunal.

Key Points from the case of Iceland Frozen Foods Ltd v Jones [1983] ICR 17 above:

Checklist for applying the reasonable range of responses test

- the tribunal should begin with the words of section 98(4) – whether the employer acted reasonably, determined in accordance with equity and the substantial merits of the case;

- the tribunal must consider whether the employer acted reasonably – not whether or not the tribunal thinks that the dismissal was fair;

- the tribunal must not substitute its own decision as to what the right course was for the employer to adopt;

- there is a band of reasonable responses to employee’s conduct in which different employers might take different views;

- the function of the tribunal is to determine whether the dismissal fell within the reasonable range of responses that a reasonable employer might take.

Other key points in judgment

- ■ The test is vital because different employers may react differently – it is whether the decision to dismiss falls within the range where a reasonable employer could have reacted the same.

- ■ Tribunals should always consider the fairness of the decision and the fairness of the procedure together.

- ■ An unfair procedure on its own is insufficient to identify the dismissal as unfair.

Following on from Iceland Frozen Foods Ltd v Jones in Haddon v Van den Bergh Foods Ltd [1999] IRLR 672 the EAT, however, later suggested that there is nothing intrinsically wrong in the tribunal substituting its own view for that of the employer, although this of course would be in effect to ignore the ‘range of reasonable responses test’.

However, in HSBC v Madden [2000] IRLR 827 the EAT suggested that no court short of the Court of Appeal can discard the range of reasonable responses test, although accepting that the Burchell test might simply go to the reason for the dismissal rather than its reasonableness. In the subsequent joined appeals Foley v Post Office; HSBC v Madden [2001] All ER 550 the Court of Appeal clarified the position:

- ■ the band of reasonable responses approach to the test of reasonableness in section 98(4) Employment Rights Act 1996 remains intact;

- ■ the test of Browne-Wilkinson in Iceland Frozen Foods is approved;

- ■ the three part test in Burchell is approved;

- ■ so the ultimate test is whether, by the standard of a reasonable employer, the employer acted reasonably in treating the shown reason for the dismissal as a sufficient reason for dismissal.

22.5.2 Procedural fairness and the ACAS Code of Practice

Another aspect to a fair dismissal is procedural fairness. The Arbitration, Conciliation and Advisory Service (ACAS) produces a Code which was first introduced in 1977. Under section 199 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 the Code can be updated regularly to take account of developments in statute. The Code is not, in itself, legally enforceable; however, employment tribunals will take its provisions into account when considering whether a dismissal is fair.

The Code does not cover dismissals for redundancy or for the non-renewal of a fixedterm contract. However, the case below does illustrate the attitude of the courts to procedural fairness and the significance of the Code.

The Code is primarily aimed at misconduct issues, poor performance and grievances. In the context of dismissal it covers disciplinary warnings and dismissals for misconduct and poor performance but not dismissals for individual redundancies or for the nonrenewal of fixed-term contracts on their expiry. However, it is important in all cases for employers to follow a fair procedure, as determined by other legislation and case law.

The code identifies fairness in the following:

- ■ raising and dealing with issues promptly and avoiding unreasonable delays;

- ■ consistency from both sides;

- ■ carrying out necessary investigations;

- ■ giving employees full information and allowing them to state their case (in this respect section 10 of the Employment Relations Act 1999 is also important in allowing the right to be accompanied at all hearings – and an employee should be advised of their right to be accompanied);

- ■ the provision of appeals;

- ■ keeping proper records.

Figure 22.1 Flow chart illustrating the process for deciding if a dismissal is fair or unfair

In addition to these general principles of fairness and procedure, in misconduct cases the Code provides that where practicable, different people should carry out the investigation and the disciplinary hearing.

22.6 Pursuing a claim for unfair dismissal

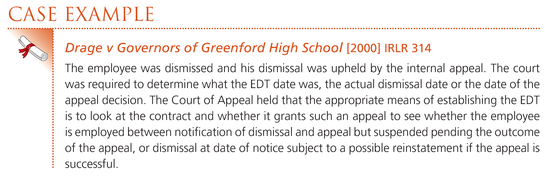

A claim for unfair dismissal must usually be made to the employment tribunal within three months of the date of the effective date of termination of the contract (EDT). An exception to this is under sections 238 and 238A of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 where dismissals following protected industrial action are concerned. Under section 111(4) a claim can be made to the tribunal before the EDT if it has been lodged with the tribunal after notice has been given, which could occur in constructive dismissal claims.

If the claimant is out of time then the tribunal has no jurisdiction to hear the case.

Under section 111(2)(b) Employment Rights Act 1996, however, the tribunal may hear claims out of time where it is satisfied that it was not reasonably practicable to present the claim in time. The meaning of reasonably practicable has been considered by the courts.

It will not necessarily be possible for the tribunal to extend the limit where the claimant argues that he has been misled by his legal advisers about the appropriate time limit. In Royal Bank of Scotland plc v Theobald [2007] UKEAT 0444 06 1001 the claimant was summarily dismissed for gross misconduct. He argued that his claim was submitted to the tribunal late only because he was erroneously advised by an adviser from a Citizens Advice Bureau that he had to complete his employer’s internal appeal procedure before he submitted his claim. The EAT held that there was nothing to suggest that it was not reasonably practicable to submit the claim on time.

When there is an internal appeal time runs according to whether on proper construction of the contract the employee is suspended pending the outcome of the appeal or not.

ACAS arbitration

ACAS arbitration schemes in unfair dismissals were initially set up by section 212A of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992. An employee can submit his claim for arbitration rather to the tribunal. Both parties must agree to go to arbitration. The scheme is for straightforward claims and the arbitrator cannot deal with jurisdictional issues such as whether there is a dismissal or whether there is sufficient continuity of employment. Evidence is heard at the arbitration hearing and the arbitrator is able to make the same awards as the tribunal.

The current government is planning to adopt suggestions from a report which it commissioned produced by the venture capitalist Adrian Beecroft. Under these plans employers would be allowed to reach settlements with employees whom they wish to dismiss which if the employee accepts would then mean that no further claim would be possible. As part of the same changes the government also plans to introduce a system of fees before a claim could be brought and also to allow judges to filter out claims that they consider vexatious before they ever reach a tribunal. The changes are clearly aimed at making it much harder for employees to enforce the rights that other legislation offers them and can only be described as a retrograde step from the perspective of employment protection.

22.7 Remedies

There are three available remedies that a tribunal might award for an unfair dismissal:

- ■ reinstatement

- ■ re-engagement

- ■ a compensatory award.

In reality the first two of these would rarely be granted because of the difficulty of enforcing and overseeing them and also because almost by definition the employment relationship will have broken down.

Reinstatement

The meaning of an order for reinstatement is in section 114 Employment Rights Act 1996.

The effect of an order of reinstatement then is as follows:

- ■ it means that the employer must take the employee back in the same job;

- ■ the effect of the order is as if the employee has not been dismissed;

- ■ as a result continuity of employment is protected;

- ■ and the employee will be eligible for all back pay, and any improvement in terms that he would have received if he had remained in work.

Re-engangement

The meaning of an order for re-engagement is in section 115 Employment Rights Act 1996.

The effect of an order of re-engagement then is as follows:

- ■ it means that the employee must be taken back on by the employer or an associated employer on terms that are comparable with those that he enjoyed when he was dismissed;

- ■ again the employee should be entitled to back pay and any improvement in terms that he would have received if he had remained in work;

- ■ and continuity of employment is again protected.

In deciding whether to make such an order the tribunal has discretion. It will take into account the claimant’s wishes, the justice of the case and also the practicability of making the order.

Compensatory award

Section 118 Employment Rights Act 1996 identifies that there are two aspects to an award of compensation:

- ■ a basic award

- ■ a compensatory award.

The nature of the basic award is identified in section 119.

The basic award then is very similar to the calculation of the statutory maximums for redundancy (see Chapter 23.5). The multiplier rose in February 2013 to £450 and rises each year. The maximum basic award in 2012 then would be 20 × 1½ (30) × £450 = £13,500.

The compensatory award is identified and explained in section 123 Employment Rights Act 1996.

As can be seen from section 123 the compensatory award is not worked out to a fixed formula but depends on what the tribunal believes is just and equitable in the circumstances subject to a statutory maximum which in 2013 stands at £74,200. In reaching a judgment on the compensatory award the tribunal takes into account:

- ■ the immediate loss of earnings – from the time of the dismissal to the award;

- ■ the future loss of earnings – a discretionary amount taking into account how long the dismissed employee may be without work;

- ■ loss of statutory rights – which is a nominal figure;

- ■ loss of pension rights;

- ■ expenses – incurred in looking for a new job.

An additional award may also be made when an employer has unreasonably refused to comply with an order for reinstatement or re-engagement. This is under section 117 Employment Rights Act 1996.

In fact the current government plans to implement various aspects of the report that it commissioned by venture capitalist Adrian Beecroft. Amongst his suggestions which the government plans to implement is a cap on unfair dismissal compensation which is likely to be set at twelve months’ wages but with a maximum below the current ceiling.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 17.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 8, pp. 361–438.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 4.4.