5

The contract of employment

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the basic contractual requirements for a contract of employment to exist

- ■ Understand the scope and significance of the statutory statement under section 1 Employment Rights Act 1996

- ■ Understand the ways in which express terms are incorporated into the contract and their significance

- ■ Understand how collective agreements become part of the contract of employment and their significance

- ■ Understand the significance of works rules to the contract and of the job description

- ■ Understand the rules regarding variation of terms in employment contracts

- ■ Critically analyse the law on the contract of employment

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

5.1 Formation of the employment contract

5.1.1 The form of the contract of employment

Although much of employment law is statutory it is also said to be based on the law of contract, and almost all working relationships are governed by contracts. The law of contract generally presumes that the parties have equal bargaining power. However, the employment relationship in reality is very unequal and in general an employee has no choice but than to accept employment on whatever terms the employer dictates, unless the person has a particular skill that is highly in demand. Therefore, the organisation has far more bargaining power. Much of employment law was created through legislation (often from membership of the EU) in an attempt to redress (i.e. to compensate for) this imbalance of power.

The employment contract conforms to the general rule that writing is not needed to create a valid contract, and contracts of employment can be made orally or by conduct. The main exceptions are contracts for apprenticeships and merchant seamen, who must have individual written agreements. It is of course also possible for the contract to be implied from the fact of the parties dealing with each other over a period of time.

Like all contracts, an employment contract requires certain key elements of formality. It will require an offer and acceptance, consideration and an intention to be legally bound. For example, the offer can be revoked at any time before it is accepted and can be conditional on medical examination, reference or subject to the enhanced criminal records check for sensitive jobs. An employment contract must also be free from vitiating factors, importantly illegality, for example attempting to defraud HM Revenue and Customs.

5.1.2 The requirement of writing

There is no general requirement that the contract of employment be in writing although of course an employment contract does require written evidence of certain terms in the required statutory statement from section 1 Employment Rights Act 1996. So a contract of employment could be implied by the conduct of the parties. While it could result from an exchange of correspondence between the parties for instance a written advertisement in a publication advertising the vacancy, responded to in letter requesting an application form, the filling in and returning of the application form, a letter inviting an applicant to interview, written notes taken at the interview, a written offer of a job following the interview, a written acceptance and a letter of appointment, it could be informally made following a casual conversation and a verbal indication of a likely starting date.

There are of course a number of exceptions where the contract must be in writing or at least elements of the agreement must be evidenced in writing. These include:

- ■ Contracts of apprenticeship must generally not only be in writing but they must also be signed by both parties to the apprenticeship deed.

- ■ Employees who operate under fixed-term contracts may in certain circumstances elect to exclude certain of their statutory rights for example to a redundancy payment; if they do so this has to be done in writing.

- ■ The Merchant Shipping Acts require that seamen’s contracts must be in writing and must be signed by both the employee and the employer.

- ■ There are also a complex set of rules in respect of rights in regard of maternity, and now paternity and adoption leave - generally an employer is entitled to request that employees seeking to exercise such rights state their full intention in writing for instance where a woman having exercised additional maternity leave states in writing her intention to return to work.

5.1.3 Formalities in the contract

As with all aspects of contract law a contract can only be formed where there is an agreement, in this case the employer has offered work and the employee has unconditionally accepted it, both parties must have promised consideration, in this case the promise of work in return for a wage, and finally both the employer and the employee intend that the employment relationship should be legally binding on them.

There is no particular form in which the offer and acceptance must be made. The offer could result from a formal written offer but it could be made orally. It is also of course the case that the means by which the potential employee finds out about the vacancy can vary. It could be that the applicant goes to the employer’s workplace asks if work is available and is told that it is. It could also of course arise through an advertisement, in which case, since the employer wishes a wide range of people to know of the vacancy so that he can select the best possible candidate, the principle in Carlill v The Carbolic Smoke-ball Co Ltd [1893] 1 QB 256 must also apply that the offer can be made to the whole world.

Inevitably an offer of employment can also be made subject to a condition precedent, for example a satisfactory reference or medical examination.

Another interesting point is what happens when an employer makes an offer of employment and then, before the employee in fact commences work, the employee withdraws the offer without any lawful justification. The issue is important of course because the employee may well have handed in notice with a previous employer and be without work but have no chance of a remedy in unfair dismissal not having completed the necessary two years of continuous service with the new employer (see Chapter 22.2), in fact having no service with the new employer.

The case reiterates an earlier decision Taylor v Furness, Withy & Co Ltd [1969] 6 KIR 488 which involved a dock worker being prevented from taking up new employment because his union membership had lapsed.

As has already been indicated, acceptance of an offer of employment could in fact come in any form. While it might involve the applicant replying to the employer in writing it could also of course be no more than a handshake at the factory gate.

There must be consideration for the agreement which would be executory, the promise of work in return for the promises of wages.

According to R v Lord Chancellor’s Department ex p Nangle [1992] 1 All ER 897 the parties must intend to create legal relations. In consequence a person agreeing to do voluntary work may not have a contract of employment.

5.1.4 Minority and the contract of employment

The position on minority is the same as the standard position for minors in contracts generally. Obviously a minor (a person under the age of eighteen) may well need to work to support himself and so must be able to legitimately enter contracts of employment. Even as early as the nineteenth century the courts recognised that an employment contract would only be binding on the minor if on balance the terms of the contract were substantially to the benefit of the minor.

In contrast if the contract is made up of terms, which are predominantly detrimental to the minor, then the contract is unlikely to be enforceable by the employer.

The courts have subsequently taken an even more progressive view of those circumstances which can be classed as a beneficial contract of service.

5.1.5 Illegality and the contract of employment

As with contracts generally it is the usual rule that a court or tribunal will not enforce an illegal contract because such contracts are contrary to public policy at common law and may even be prohibited by statute. In either case the contract may prove to be unenforceable by either party.

So where an employment contract is tainted by illegality and the employee is aware of that it is likely that the employee will lose statutory rights as a result.

A contract that is legally formed but then is illegally performed in some manner is not automatically unenforceable and the fact that some aspects are tainted with illegality will not necessarily make the whole contract unenforceable.

It is usually the employee’s knowledge of the illegality which leads to a loss of rights under the contract but where it was intended that the employment should be carried out lawfully but some of the work is then tainted with illegality the question for the courts is then whether it is possible to sever the illegal parts from the main contract to avoid the employee losing rights altogether.

In general a contract that has the purpose of defrauding the revenue is tainted with illegality and will result in a loss of rights for the employee.

However, if what the employee receives without payment of tax cannot be said to be part of the regular wages then this may not be classed as defrauding the revenue and will not therefore taint the contract with illegality. In Lightfoot v D & J Sporting Ltd [1996] IRLR 64 an arrangement to pay part of the employee’s salary to his wife was held to be tax avoidance rather than tax evasion and was therefore not unlawful. The difference between tax evasion where a person takes steps to not pay tax that he is already bound to pay and which is unlawful, and tax avoidance whereby people in a position to hire an accountant and therefore do not pay the tax that they might be expected to is an interesting distinction which the current government is still trying to explain to the electorate. In the case of most working people the distinction would be lost since their tax is paid at source on a PAYE basis so that they would not be in a position to try either.

It is usually the employee’s knowledge of the illegality which leads to the employee losing rights under the contract of employment.

However, the fact that the employee knows of the illegality will not in every case prevent the employee from enforcing the contract. This is particularly so where the employee will not benefit from the illegality in any way.

It is also the case that the illegality must be linked to the actual subject of the claim for the claim to be affected by the illegality. In this way for instance it may still be possible to bring discrimination claim even though aspects of the employment involve an illegality.

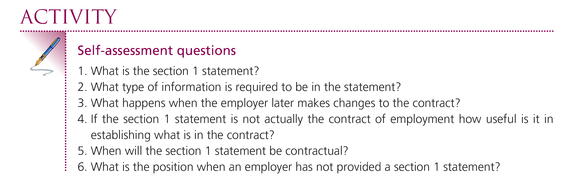

5.2 The statutory statement

5.2.1 The legal status of the statement

As we have already seen in 5.1.1 there is no general requirement for a contract of employment to be in writing. Nevertheless, to avoid a dispute, it is useful for the employer and new employee to record the terms in writing which limits the scope of any later dispute about the terms of the contract.

In order to ensure that all new employees receive details of the essential terms of their employment, section 1 of the Employment Rights Act 1996 requires that employers must provide employees whose employment is to continue for more than one month with a written statement of particular terms of their contract. This written statement must be given to employees no later than two months after their employment begins. Section 1 indicates a variety of information which must be provided in the statement or which the statement must indicate where they can be found. These are listed in Figure 5.1.

Written Particulars Required in the S1 Statement

Section 1 Employment Rights Act 1996 – within eight weeks of employment the employer must provide the employee with a written statement of particulars containing the following:

If there are any changes to any of the particular terms within the written statement then under section 4 Employment Rights Act 1996 the employer is bound to give the

Figure 5.1 Chart illustrating the information that must be contained in the statement of particulars of employment as required by section 1 Employment Rights Act 1996

employee a new written statement containing details of the change at the earliest opportunity but no later than one month after the change.

The written statement required by section 1 is not a contract of employment.

This was later confirmed in System Floors (UK) Ltd v Daniel [1982] ICR 54.

A contract creates the rights and duties of the parties. The written statement required under section 1 merely declares what they are after they have been agreed, but these can be inaccurate. The statement therefore meets the employer’s statutory obligations, but is not a contractual document. If the document was held to be a written contract it would be presumed to be an accurate record of what was agreed. It would therefore be difficult to persuade a court otherwise.

As a result section 1 can only be seen as evidence of the contractual terms not the contract itself. Although of course it could prove to be quite powerful evidence.

It follows that, while the section 1 statement can be evidence of terms in the contract it will not actually be contractually binding on its own unless the parties agree that it is contractually binding. One way that this could be done is by the employee signing to accept that it is contractual.

An example of a written statement of particulars is given below.

5.2.2 Enforcement of the statement

If an employer fails to provide a written statement, or provides an inaccurate or incomplete statement or fails to provide an employee with a statement of changes, then under section 11 Employment Rights Act 1996 the employee may complain to an employment tribunal. The employee could continue in employment and do this or, if the contract has been terminated, then it would have to be within three months of the date of termination.

Where this is the employee’s only claim then the only remedy will be a declaration from the tribunal which either confirms the written particulars or amends them but the tribunal cannot merely substitute its own of what the terms should be. In Cuthbertson v AML Distributors [1975] IRLR 228 for example the tribunal felt that it was not appropriate to state what notice was reasonable for a senior executive.

If the employee has succeeded in another claim, for example for unfair dismissal, then, in addition to the declaration, under section 38 Employment Act 2002 the employee may also receive compensation of between two and four weeks’ pay.

5.3 The incorporation of the express terms

5.3.1 The range and character of express terms

All contracts contain terms that have been incorporated into them which set out the obligations of the parties and this is no different in contracts of employment. Express terms are

Figure 5.2 Sample statutory statement of particulars

those that have been written into the contract or they may have been agreed by the parties orally. Express terms usually deal with such matters as pay, hours or work and holiday entitlement and they are often in any case affected by statutory rights and restrictions, for example, the right to equal pay, the minimum wage, and the rules on working time all affect what the employer can put into the contract on these matters. As a result express terms can be overridden by implied terms, particularly when these are statutory.

The parties to an employment contract could agree on any terms, although except in very rare cases the terms would be dictated by the employer. They must of course be subject to general principles of law, so as we have seen in 5.1.5 there would be implications if the contract was based on illegality and an employee might find it difficult to enforce such a contract. Similarly the contract may reflect an inadequate balance between the parties but it could not be based on slavery.

The express terms usually contain the same information as that which is included in the written statement of particular terms required by section 1 Employment Rights Act 1996, so they may include details on pay, holiday entitlement, duties required notice and many others. The express terms would usually be of three distinct types:

- ■ specific terms agreed by the parties;

- ■ everything required to be in the section 1 statement;

- ■ terms contained in other documents specifically referred to in the section 1 statement (an example of this latter might be details of paid holiday entitlement in excess of that required by law).

These terms can be discovered in the case of dispute by looking at what the parties said or wrote when they made the agreement. Obviously they are simpler to find if they are in writing. However, even where they are expressed, it is still for courts and tribunals to interpret them and they will do so by looking at the general practices in the particular industry. Where terms are not expressed they may be implied.

5.3.2 The significance of the express terms

Not all terms are expressed in a written agreement or even indicated orally in negotiations, many are implied either by custom, by law or by statute or other statutory provision. The range of possible terms can be illustrated in diagram form as in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 Diagram illustrating how terms in the employment contract originate

It is always preferable for express terms to be in writing so that there is no disputing them and they are clear to all parties, including a tribunal in the case of a dispute. In Stubbs v Trower, Still & Keeling [1987] IRLR 321 there was a dispute when a firm of solicitors failed to properly express the requirement of passing the necessary professional qualifications before a post could be taken up. So the written statement needs to accurately represent the actual agreement between the parties to avoid disputes.

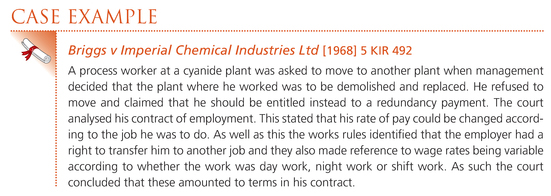

It is possible for either party to accept breaches of the terms of the contract by the other party. In the case of a breach of terms by the employee the employer could count this as grounds for dismissal. In the case of a breach of the terms by the employer the employee could claim for constructive dismissal. In either case established tests of fairness or unfairness will be used. This can be seen in two contrasting cases.

In general advertisements may be indicative of express terms in the contract of employment and so be a means of a tribunal determining what the express terms are in the event of a dispute. However, if these are inconsistent with the express terms they will not override them.

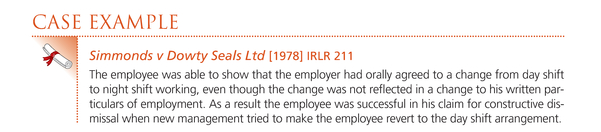

It is possible, however, that express oral terms can override details provided in the statutory statement and present a more accurate representation of the contract.

5.3.3 Interpreting the express terms

Whatever the parties may have agreed which can then be classed as the express terms of the contract it is inevitable that, if there is a dispute then the courts will be called on to decide if an alleged term is in fact consistent with the employment relationship.

However, despite the fact that tribunals and courts will be called on to interpret the precise meaning of terms, however, well or badly expressed, one thing that they cannot do is to reach decisions that would in effect change the job description, and thus the contractual terms.

The tribunal is of course entitled to consider extrinsic material such as job advertisements in order to ascertain the meaning of terms. In Tayside Regional Council v McIntosh [1982] IRLR 272 for instance the EAT held that a requirement for 'qualifications' need not be expressly stated in a contract of employment, as it may be inferred from the job advertisement or even from the nature of the job. However, as we have seen in 5.3.2 such material cannot be used to override express terms as in Deeley v BREL [1980] IRLR 147 where the actual role was Sales Engineer and the use of the word Export in the job advertisement was not definitive.

The traditional view was that, if the employee agreed a term then he was bound by it, however, harshly it might apply. However, the modern view is that they should also express terms that should be exercised reasonably and they should not be inconsistent with the implied duty of mutual trusts and respect (see Chapter 7.2.5).

The courts will not accept that an ambiguous provision in the contract can act to the employee’s detriment. Similarly courts will not allow an employee to enforce anything that is too vague or ambiguous.

5.3.4 The advantages and disadvantages of express terms

Advantages

- ■ Where the parties have expressed themselves on the terms of the contract, and particularly where the terms have been put in written form then there is likely to be less room for dispute. If the terms are clear then there should not in fact be any room for dispute.

- ■ If this is the case then inevitably there is a consequent saving of time and money because there is no point an employee arguing about something that he had agreed to at the time of making the contract or at least was plainly aware of at the time of contracting.

- ■ Express terms can be broadly stated, and we have seen this in the case of mobility clauses and so may give much greater scope to the employer for flexibility. Obviously employers wish to get the greatest productivity from employees. A well drafted written contract of employment with clearly stated express terms provides the greatest chance of this unless of course express terms conflict with the implied duties (see Chapter 7) or any statutory provisions which may override them.

Disadvantages

Great care should be taken in drafting a written contract of employment otherwise an employer might actually end up creating more problems – there are two obvious ones:

- ■ The express terms may be drafted too narrowly to cover the employer’s actual needs – then if the employer tries to extend what he requires from the employee he may be in breach of contract.

- ■ Alternatively, even though the express terms may be drafted well they may still be subject to narrow interpretation by the tribunal – in which case the employer still has not achieved the desired flexibility from the contract.

Conclusion

Since the employer is obliged in any case to provide a written statement of particulars and give this to the employee within eight weeks of the commencement of employment it is possibly better to provide a more detailed written contract at the commencement of employment. The employee is then in no doubt what the terms of his employment are and it avoids later disputes. The employer will clearly benefit by including as broad terms as are possible.

5.4 Collective agreements

5.4.1 The nature of collective agreements

A collective agreement is defined in section 178 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 as 'any agreement or arrangement made by or on behalf of one or more trade unions and one or more employers or employers' associations'. It is an agreement made through collective bargaining between the unions and the employers and such agreements are generally presumed to have no effect in law unless they are incorporated into the contract. There are three ways in which they may be incorporated into the contract and become binding on the employer and employees:

- ■ If they are expressly incorporated into the contract – this would be in a clause identifying that the employee is bound by the agreement and there may also be reference to collective agreements in the section 1 statement.

- ■ There might be implied incorporation through conduct for instance which would in effect be custom and practice.

- ■ Incorporation of collective agreements might result from the trade union negotiating with the employer, in effect being the agent of the employees and acting on their behalf.

Collective agreements may define the relationship between the trade union and the employer which will not usually form part of the contract of employment, but they can also define the terms and conditions of those employees who fall within the agreements reached between trade unions and the employer. Often such agreements are made on a national scale but there can also be local agreements which may be specific to a branch of a trade union and a specific workplace. These are still covered by the same rules.

5.4.2 Express incorporation of collective agreements

The most obvious way for terms from a collective agreement to be incorporated in the contract of employment is for an express provision to be inserted in the contract to that effect.

The section 1 statement is of course another obvious method by which the collective agreement can be incorporated into the contract.

In order for the terms arising from collective agreements which affect the employee’s working conditions to be incorporated they clearly must represent the actual contractual intention of the parties.

One of the benefits of express incorporation of an arrangement with trade unions and therefore collective agreements made with them is that this may mean that the contract need not be amended on each re-negotiation. The employer will simply have stated in the contract that the employee is subject to the collective agreements negotiated with that trade union.

It is of course true that not every collective agreement is in fact always suitable for incorporation into the contract of employment as they may simply concern the relationship between the employer and the trade union.

It would also be true that an employee cannot rely on a term in a collective agreement when the term is in fact procedural rather than conferring any substantive individual rights on employees.

Where the terms of national and local agreements conflict then one approach has been that the most recent in time should prevail. This is how the problem was resolved in Clift v West Riding CC [1964] The Times 10 April 1964 where the employee was paid less under a local agreement than he might have been under a national agreement but because the local agreement was made after the national agreement it was the local agreement that the employee was held to be bound by.

However, it is a question of fact in each case which agreement will be taken as the one which prevails.

5.4.3 Implied incorporation of collective agreements

Collective agreement can also be incorporated in the contract of employment by implication which will usually involve operation of the 'officious bystander test' (see Chapter 7.1.2). This could occur because in certain industries there is almost an assumption that the terms developed from agreements between the recognised trade unions and management become contractual. Terms resulting from collective agreements are likely to be implied into contracts of employment where there is long term acceptance of the process.

It is also possible that terms agreed in a collective agreement can be incorporated into the contract of employment by custom and practice following the principle in Sagar v Ridehalgh [1931] 1 Ch 310 that the practice is reasonable, certain and notorious (see Chapter 7.1.2).

5.4.4 The effect of collective agreements on non-union members

A trade union may well be the agent of its members but of course it has no real relationship with employees who are not members. As a result collective agreements will only be contractually binding on employees who are not members of the trade union or who are members of a different trade union to the one that is recognised by the employer if they have been expressly incorporated into the contracts of those employees. If they have not been expressly incorporated then the terms reached under a collective agreement cannot apply to those employees.

Singh concerned an employee who was no longer a member of a union. It is also possible to apply the principle to an employee who is a member of a trade union other than the one with which the collective agreement has been reached.

It could of course be possible for there to be implied incorporation of the agreement (see Carlton Henry & Others v London General Transport Services Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 488 in 5.4.3 above).

5.4.5 No strike clauses

Such clauses are now covered by section 180 Trade Union & Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 which identifies the restrictions on their use.

So provisions limiting industrial action arising out of a collective agreement are only incorporated if:

- ■ the collective agreement is in writing;

- ■ the agreement expressly states that the no-strike clause is incorporated into the contract and it is actually incorporated;

- ■ the notification of the agreement is reasonably accessible in the workplace in working hours.

Besides this of course a strike is always a breach of contract so this may in fact reduce the impact of section 180.

5.4.6 Changing or ending collective agreements

The agreement if incorporated cannot be unilaterally varied or ended. This can be seen in Robertson v British Gas [1983] ICR 351 in 5.2.1 above. Despite the collective agreement between the employer and the union having no legal force as between the signatories it was incorporated into the employee’s contractual terms and the withdrawal of the bonus scheme was therefore a unilateral change to the contract which the employee had no entitlement to make.

Unilateral termination may, however, be possible where the contract in fact allows for it.

It is of course possible to change or end the agreement through a lawful agreement and a lawful notice of the agreement to the employees affected.

5.5 Works rules

5.5.1 The nature and effect of works rules

All employers have works rules and some present these in handbooks which are sometimes given to employees but in any case are available to employees. The works rules could include a variety of issues to do with the employment which may even include references to disciplinary proceedings, health and safety as well as sickness procedure and holiday entitlement. The problem with handbooks is that they may mix contractual and non-contractual matter. The distinction is clearly important because contractual terms of employment can only be changed by agreement with employees whereas non-contractual rules are seen as management prerogative and can be changed unilaterally.

If the provisions of the rule book are seen as merely rules rather than contractual terms then the employer is entitled to change the rules and introduce new rules and employees would not be able to challenge this even though the changes may be significant.

In this way the fact that changes in the rules acts harshly on particular employees is of no real consequence. There is no automatic repudiation of contract by an employer based purely on making changes to the works rules.

Often where there are a large number of detailed rules in the rule book dealing with practical issues, then a court may simply infer that these are not contractual but merely a set of instructions to the employee on how the contract should be carried out. However, a court might still see a failure to carry out the rules as having contractual consequences.

In Peake v Automotive Products [1977] QB 780 (later Automotive Products Ltd v Peake [1977] IRLR 365 in the Court of Appeal) the EAT identified that works rules were in fact no more than non-contractual administrative arrangements. Nevertheless, provisions in works rules have still been enforced by courts even against blameless employees and leading to what may be seen as relatively harsh results.

Rules should be clear and unambiguous and should still be reasonable in character so that an autocratic approach to the rulebook may not be accepted by the court. In Talbot v Hugh Fulton Ltd [1975] IRLR 52 which involved a works rule that led to an employee being dismissed for having long hair, the court suggested that such rules must have some justification for example based on hygiene or safety.

The courts have found in certain circumstances that works rules can be contractual in nature despite their unilateral character.

In general works rules are more likely to be seen as contractual where express mention of the rules is made in the contract itself.

The dismissal was held to be fair. In effect the employee had disobeyed a lawful and reasonable order which was necessary to the maintenance of proper conditions within the process. It was not merely a works rule but was also a contractual requirement.

The ultimate analysis of whether a works rule is in fact incorporated into the contract is for the tribunal or court to determine and this analysis may turn on the character of the clause.

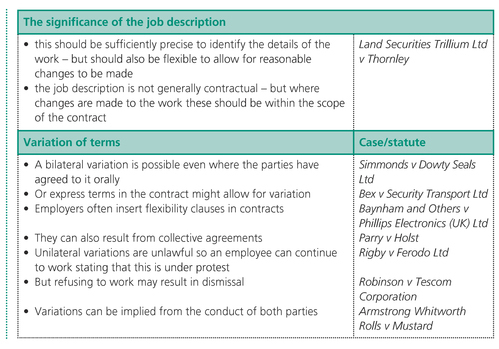

5.5.2 The significance of the job description

It is common for employers to produce a document detailing the employee’s duties and this is generally referred to as the 'job description'. Indeed it is also common for potential applicants for posts to receive this along with an application form when they first enquire about the job. The advantage of the potential applicant receiving the job description before applying is that they will be able to decide whether or not they have the necessary skills and aptitude so that they are capable first of being given the job and second of doing it.

There is no required format for a job description but sensible employment policy would suggest that it should achieve two significant purposes:

- ■ first it should be sufficiently specific that an applicant and indeed an employee is able to identify the precise details of the work;

- ■ second it should also be in language that is sufficiently flexible to allow the employer to make reasonable variations to the work.

Particularly with small businesses rigid demarcation lines between particular duties are unrealistic and the workforce would need to be reasonably flexible both in terms of the work done and the circumstances surrounding it. (In the 1950s through to the 1970s it was not uncommon for a stoppage to occur because a particular worker was not allowed to carry out another worker’s work. For example a maintenance engineer having repaired a piece of machinery might be prevented from cleaning up the resulting mess because this was the job of a labourer. Inevitably this had a major effect on productivity. Small businesses simply could not afford for this to happen now.)

In this respect the scope of the contract is inevitably different to and broader than the scope of the job description so that the job description is not contractual although it can be strong evidence of contractual terms. On this basis the job description can develop over time and can be unilaterally altered as long as it still falls within the scope of the contract.

However, the mere fact that the employer includes a flexibility clause in the job description does not necessarily mean that the employer is able to change the fundamental nature of the work without consulting the employees. Where an employer tries to make changes to the employees’ duties without their agreement these must fall within the scope of the contract to be lawful and binding on the employee.

5.6 Variation of contractual terms

Over the course of most employment relationships, an employee’s terms of employment are bound to change in a number of ways. While the recession may have limited annual pay increases (particularly those that bring the wage in line with inflation), they are quite common. Employees are often promoted which will normally mean quite a significant change to their contract of employment. However, these types of changes will normally happen by mutual consent and are unlikely to cause any legal or practical problems for employers.

Occasionally, however, an employer may wish to make other changes to the contract of employment that the employee is less happy to accept. There are two main reasons when an employer will wish to change terms in a contract, the first being economic circumstances resulting in a need to reorganise the employer’s business. This may result in specific changes to the terms of an employment contract, such as changes to pay rates, bonus and commission structures, job content and the place where an employee is required to work. The second reason where change is normally apparent is where the employer is going through a programme of harmonisation of terms of employment across the business. The employer may wish to move all employees on to standard terms of employment, where previously they were all on a variety of different contracts. This may have been the result of a previous business merger for example.

At common law an employment contract like any other contract may be amended only in accordance with its terms or with the agreement of all parties. The law will not allow employers to use their greater bargaining position to impose contractual variations on employees against their will.

5.6.1 Bilateral variations

An express agreement is the most effective way of varying a contract of employment. From a legal and practical perspective, obtaining the agreement of the employee to the change is the simplest option for employers.

The employee’s express agreement to a variation of the terms of the contract must be given voluntarily and should be free from duress. A verbal agreement to the change could be sufficient but employers should try to obtain a written confirmation of the agreement. The terms of an employment contract are determined at the start of the employment relationship and strong evidence of mutual agreement will be required to establish that they have been varied. This does not mean, however, that the written evidence will always take precedence over what has been said and done by the parties.

Ultimately express terms in the contract might allow the employer to make significant variations in the terms and the employee would be bound by the changes.

Clearly the easiest way for the employer to vary the terms of the contract is to include a flexibility clause in the contract. However, because these clauses aim to give the employer wide discretion to change any term of the employment relationship, so as to evade the general rule that changes must be mutually agreed, courts and tribunals will only rarely enforce such clauses which remove rights gained under the contract.

Changes in terms of employment which are negotiated by an independent trade union may be effective in amending an employee’s contracts of employment. This will generally occur where the contract terms include an express provision giving effect to the results of collective bargaining. Any changes to terms which are agreed through that process may be binding on employees. This may even apply to employees who are not members of the relevant trade union.

In the absence of an express provision giving effect to the results of collective bargaining, a term to that effect may be implied as a result of a custom or practice of collectively negotiating important changes to individual contracts of employment. Clear evidence is required to establish such a custom, but the standard of proof required is the balance of probabilities (see Carlton Henry & Others v London General Transport Services Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 488 in 5.4.3 above).

5.6.2 Unilateral variations

An employer who imposes a contractual change without the employee’s express or implied agreement will be in breach of contract and, as a matter of law, the original terms of the contract will remain in place. If the employee, however, continues working under the new terms, without protesting in any way for a number of weeks, the employer can argue that the employee has implicitly accepted the changes through their actions. This is otherwise known as 'acceptance through practice'. This practice is evidence that the court or tribunal will accept.

Where the employee does not accept the unilateral change, they may respond to the breach in a number of ways. First they could continue to work under protest. So the employee should make it clear that they are not accepting the change. An employee will not lose the opportunity to remain in employment and sue on the employment contract just because the employer’s actions in imposing the change amount to a repudiatory breach of contract which would entitle the employee to resign and claim constructive dismissal.

The employee could also refuse to work under the new terms which would only be possible where the new terms affect the employee’s day-to-day working arrangements such as job duties and working hours. If an employee refuses to accept a change in terms but does not resign as a result, the employer is left with a predicament over what to do with the obstructive employee. The employer may be forced to dismiss the employee.

5.6.3 Implied variations

A variation can also be implied where it can be inferred from the conduct of the parties.

Statute may also result in employers having to make changes to contracts of employment. For instance the National Minimum Wage Act 1998 allows the Secretary of State to pass secondary legislation which changes the National Minimum Wage that workers receive. This change does not need the agreement of either the employer or worker. The Working Time Regulations 1998 also have the same effect of requiring changes to be made to contracts of employment. These changes have had a significant effect on pay rates, annual leave entitlement, rest breaks, working hours and night work.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 3.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 4, pp. 154–167, p. 172.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 3.5.2.2–3.5.2.3.