4

Employment status

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the basic character of employment

- ■ Understand the limitations of the statutory definition

- ■ Understand the differences between an employee and an independent contractor

- ■ Understand the purposes of distinguishing between employees and independent contractors (the self-employed)

- ■ Understand the tests for establishing whether someone is an employee or not

- ■ Understand those types of situations where work is atypical and the tests do not easily apply

- ■ Distinguish between employees and independent contractors

- ■ Assess the impact of the distinction on the individual and the person hiring their service

- ■ Critically analyse the concepts of employment, self-employment and atypical workers, the reasons for distinguishing and the impact on the employment relationship and on employment rights

- ■ Apply the tests to factual situations to determine whether an individual is an employee

- ■ Apply the outcome to a variety of rights

4.1 Introduction

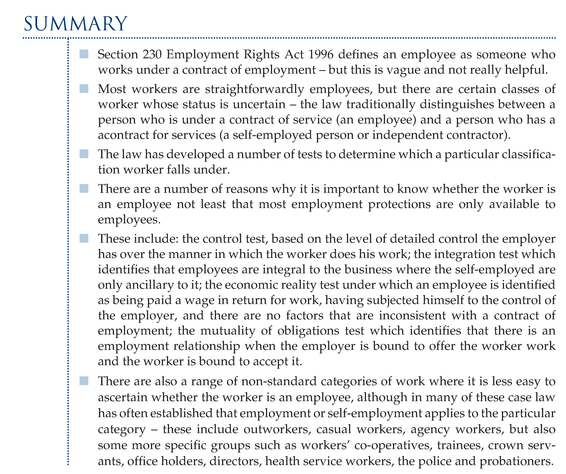

There are a multitude of rights and responsibilities that exist in the employment relationship. However, before we can begin to study or understand them we need first to consider to whom they apply because in most instances they apply only to employees and employers, and at all times we must distinguish an employee from an independent contractor, a self-employed person.

On the face of it the distinction may seem simple but it is not always so. While most people work they do so in different circumstances and under different conditions.

With certain types of working situations it is not possible to determine at first sight whether in fact a person is employed under a contract of service or not. It will often be in the interest of an 'employer' to deny that the relationship is one of employment to avoid responsibility for employment protection rights. Definitions such as that contained in the Employment Rights Act (see 4.2.1 below) that the employer is a person employed under a contract of employment are not really of much use in determining whether a person is in fact an employee. It has also been suggested in WHPT Housing Association Ltd v Secretary of State for Social Services [1981] ICR 737 that the distinction lies in the fact that the employee provides himself to serve while the self-employed person only offers his services. This is no greater help in determining whether or not a person is employed.

Besides this a number of different types of working relationship are not so easy to define. 'Lump' labour was common in the past, particularly the 1960s and 1970s. The lump, as it was called at that time, referred to practice where workers in many trades in industries like construction such as carpenters, bricklayers and painters for example would move from site to site without formally being taken on as employees of contractors hiring labour but would simply work for cash in hand. This gave the 'employee' the advantage of not paying any tax or National Insurance. It gave the 'employer' the advantage of possibly paying less in wages but certainly also of not paying the employer’s National Insurance contributions. In effect it defrauded the revenue. Casual and temporary employment is possibly even more prevalent today and many major companies and organisations rely on the use of agency staff or casual labour.

Over the years the courts have devised a number of methods of testing employee status. They all have shortcomings. Some are less useful in a modern society than others.

4.2 Distinguishing between employment and self-employment

4.2.1 The employment relationship

The effective starting point when deciding whether employment law rights apply in any given situation is to ask the question first: is the person an employee? Following the Industrial Revolution, the only relationship that existed was that between the 'master and servant'. Therefore a person’s employment status was easy to define. Today, however, the question of whether an individual is an employee is not always easy to answer.

On the surface it seems as though it should be simple and straightforward. However, even a brief examination of the statutory definition shows that it is not.

The statutory definition is therefore fairly ambiguous and does not really help to provide any understanding as to who is actually an employee. Under the definition in s230(2), a person is an employee if he works under a contract of service. However, there is no statutory definition of a contract of service and the common law has developed rules to help distinguish it from a contract for services. In basic terms an employee working under a contract of service agrees to serve another whereas someone who is an independent contractor or self-employed works under a contract for services and agrees to provide certain services to another.

An employer could be a sole trader, a partnership, a company, an unincorporated association or even a private individual. Employers’ needs can also vary enormously when hiring 'labour'. They may want permanent staff or only temporary, part-time or casual staff, and they need highly skilled staff for specific tasks. This all impacts on the nature of the employment relationship.

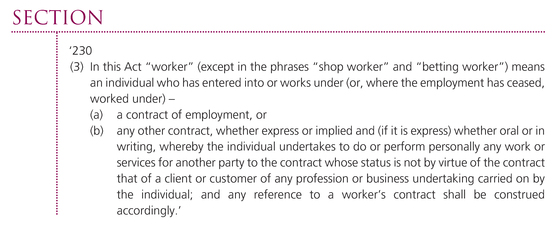

The picture has become even more confused in recent years as a new statutory status of 'worker' has evolved. A worker is defined under s230(3) ERA 1996:

In Byrne Brothers (Formwork) Limited v Baird [2002] IRLR 496 the EAT stated that a 'worker' had a lower set of qualifying criteria than an 'employee'. So a person may not qualify as an employee but still be entitled to certain rights by being qualified as a worker. Where a person is, on balance, classed as self- employed but there are some factors which point towards employment, it may be possible for him to qualify as a worker. While workers have less extensive employment protection rights than employees, increasingly new statutory employment protections cover workers as well as employees, for example working times and the National Minimum Wage.

The section, as it goes on, is no more illuminating.

The common law tests of employment status are therefore very important.

4.2.2 The purpose of distinguishing between employment and self-employment

Distinguishing between who is classed as an employee and who is an independent contractor is important for a number of reasons. Examples include:

- ■ Implied duties – employers and employees have obligations that are implied into the contract between them (for example, the mutual duty of trust and confidence, the duty of faithful service, etc.).

- ■ Employment protection – the majority of the core legal protections only apply to employees, most particularly the rights on termination of employment granted under ERA 1996, the right not to be unfairly dismissed and the right to a statutory redundancy payment. 'Workers' enjoy limited protection under employment law – for example, the right not to have unlawful deductions from wages, minimum wage, rest breaks, paid leave and data protection.

- ■ Health and Safety – employers owe employees statutory duties relating to health and safety. Independent contractors may not be covered under these duties. They will be covered, however, under the employer’s common law duty of care.

- ■ Vicarious liability – an employer is vicariously liable for acts done by an employee in the course of his employment. This vicarious liability does not usually extend to independent contractors or self-employed individuals (although it may do if the employer has directed the independent contractor to commit the tort Ellis v Sheffield Gas Consumers Co [1853] 2 E & B 767).

- ■ Taxation – the tax and social security treatment of a person providing services depends on their status. Employers make deductions for income tax under schedule E (PAYE) from salaries and the self- employed are taxed under schedule D annually on a previous year basis and are able to set off certain expenses against tax.

- ■ Insurance – an employer is required to take out employer’s liability insurance to cover the risk of employees injuring themselves at work. Self-employed individuals or independent contractors may not be covered by this insurance and may need to take out their own insurance.

- ■ VAT – an independent subcontractor may have to register their business for Value Added Tax.

Independent contractors may be better off financially but can be disadvantaged if injured. While the self- employed benefit by taking all of the profit from their work they also stand any losses and also have to find their own work. Employees have relative security by contrast and know that they receive a wage each pay period but they lack independence. So there are advantages and disadvantages in both classifications.

The differences are generally determined by the consequences of whatever classification. As a result there is inconsistency in the methods of testing employee status according to who it is that is doing the testing. For instance the tax authorities, when testing employee status, are only interested in determining the nature of the person’s liability to pay tax, and not any other purpose. So the fact that a person is paying Schedule D tax is not necessarily definitive of their status as self-employed. In the case of industrial safety inspectors investigating breaches of health of safety law they may have less concern with whether an injured person is an employee and more with the fact that the regulations have been breached and caused injury.

4.3 Tests of employment status

4.3.1 Introduction

Because there is no adequate statutory definition of employment a variety of tests for establishing employment status have been devised by the courts over many years.

The diverse and increasingly complex and technical character of work means that it is difficult for any test to be seen as an absolute test or one that will be definitive in all

Figure 4.1 Chart illustrating the consequences of distinguishing between employees and self-employed

circumstances. The tests having originated under the old 'master and servant laws' (see Chapter 1.4.1) are in part not really relevant in more modern circumstances and some have been discarded.

Whichever test may seem appropriate in a given situation, the general approach in modern times has been for judges to treat each case on its merits and to consider all of the various factors that may point to either employment or self- employment and to balance those factors accordingly.

The tests are nevertheless important as many of them may still be appropriate in particular circumstances.

There have been four tests:

- ■ the control test;

- ■ the integration or organisation test;

- ■ the economic realty or multiple test;

- ■ the mutuality of obligations test.

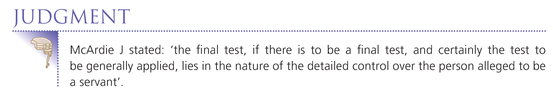

4.3.2 The control test

The control test is the oldest test for establishing employment status and it comes from a time when the only employment relationship that existed was that between the 'master' and 'servant'. It considers the degree of control and supervision that is exerted by the employer over their staff. The classic definition of the master servant relationship comes from the judgment in Limland v Stephens [1801] 3 Esp. 269:

The control test was based very firmly on this style of relationship. An early definition was given in Yewens v Noakes [1880] 6 QB 530 where in a tax law case, the Court of Appeal held that a clerk who earned £150 a year did not fall within the definition of servant.

The test was then further developed and explained in:

Often a worker would have been unable to gain a remedy without proving that the test applied. In Walker v Crystal Palace Football Club Ltd [1910] 1 KB 87 a footballer was considered to be an employee of the club and therefore able to claim compensation for an injury received in a match accident under the Workmen’s Compensation Act 1906.

The implication is that the master not only controlled what was to be done and when it was to be done, but also the manner in which the work was done. In the case of simple forms of employment prevalent when the master and servant laws were developed, such as farm labouring or domestic service, then clearly this level of control could be easily identified and the test worked well.

However, the test is still important as in today's employment market an employee would normally be subject to some form of control or supervision by the employer. Lord Thankerton in Short v J W Henderson Ltd [1946] 62 TLR 427 identified many key features that would show that the master had control over the servant. These included the power to select the servant, the right to suspend and dismiss, the payment of wages and the right to control the method of working (this has sometimes been referred to as the indicia test – it has also been criticised as inadequate because the first three only point to a contract not necessarily to employment and the last is merely the control test). There is also the power to terminate and, in particular, to subject the employee to disciplinary procedures and to manage the relationship by issuing orders and directions. Many of the cases, however, have tended to focus on the extent to which the individual is controlled in the manner in which they carry out their tasks.

Such a test is virtually impossible to apply accurately in modern circumstances. Nevertheless, there are circumstances in which a test of control is still useful; in the case of borrowed workers.

However, even in the nineteenth century in the case of more sophisticated types of work requiring technical knowledge and expertise that was likely to be beyond that enjoyed by the master then it was apparent that such a simple test was not really workable. As technology advanced in the twentieth century certain work became even more specialist. The classic example of this is in medicine. Hospitals very often employ managerial and administrative staff with backgrounds for example in retailing or in financial services or other businesses. It would be difficult to say that these people had the expertise to be able to ‘control’ surgeons carrying out highly complex surgical procedures or even to understand what was going on if they attended operations. This is shown in Cassidy v Ministry of Health [1951] 2 KB 343 where it had to be decided who was in fact liable and the court felt that hospitals and health services should always be responsible for the work done in them.

4.3.3 The integration or organisation test

The degree of integration into the employer's business was identified as a test in the early 1950s by Lord Denning.

Figure 4.2 Diagram illustrating the operation of the control test

The basis of the test is that someone will be an employee whose work is fully integrated into the business, whereas if a person's work is only accessory to the business then that person is not an employee. In other words he is considered to be 'part and parcel' of the employer's organisation. A self- employed person or an independent contractor is more likely to perform duties which are ancillary to the main business of the employer.

Lord Denning explained that, according to this test, the master of a ship, a chauffeur and a reporter on the staff of a newspaper are all employees, where the pilot bringing a ship into port, a taxi driver and a freelance writer are not. The test can work well in some circumstances particularly in the case of very skilled employees where the control test may not be adequate, doctors being an obvious example.

However, there are still defects. For instance part- time examiners may be classed as employed for the purposes of deducting tax, but it is unlikely that the exam board would be happy to pay redundancy when their services were no longer needed. Another problem in modern employment is that many businesses outsource parts of their work and this would make application of the test difficult.

Figure 4.3 Diagram illustrating the operation of the integration test

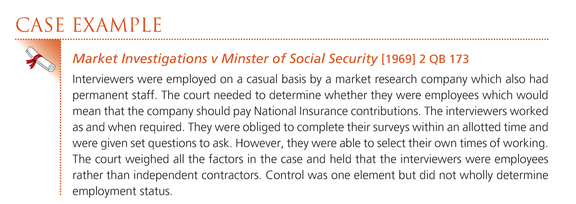

4.3.4 The economic reality or multiple test

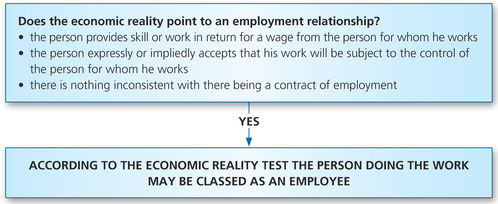

The courts later recognised that a single test of employment is not satisfactory and may produce confusing results. As a result a new test, the economic reality test, was developed. This is sometimes known as the multiple test since all the various factors need to be considered.

So the answer under the test is to consider whatever factors may be indicative of employment or self- employment. In particular, three conditions should be met before an employment relationship is identified:

- ■ The employee agrees to provide work or skill in return for a wage.

- ■ The employee expressly or impliedly accepts that the work will be subject to the control of the employer.

- ■ All other considerations in the contract are consistent with there being a contract of employment rather than any other relationship between the parties.

In respect of this last point the test has been developed over time so that all the relevant factors in the relationship should be considered and weighed according to their significance. It is not a case of simply totalling up factors which indicate employment and factors which indicate self- employment and running with the one with the most factors. The factors that will be considered include:

- ■ The method of payment – an employee usually receives a wage, regular payments for a defined pay period whereas a self-employed person will usually be paid a price for a whole job.

- ■ Tax and National Insurance contributions – an employee usually has tax deducted out of wages under the PAYE scheme under schedule E and also has Class 1 National Insurance contributions also deducted by the employer from wages each pay period, so an employee has no choice but to pay tax and National Insurance and is usually unable to claim expenses against tax. A self-employed person on the other hand usually pays tax annually under schedule D on a previous year basis and is able to set expenses off against tax, and makes National Insurance contributions by buying Class 2 stamps or Class 4 beyond a certain level of income.

- ■ Ownership of tools or plant or equipment – an employee is less likely to own the plant and equipment with which he works particularly when this involves large expensive items, however, the self-employed will very often need to provide their own tools although with large expensive equipment this may mean hiring it.

- ■ Self- description – a person may describe himself as one or the other and this will usually, but not always, be an accurate description. So self- description may be strong but not necessarily definitive evidence of employment status. Courts look more to the substance of the relationship rather than just accepting the description as can be seen in the following two cases. In Massey v Crown Life Insurance [1978] IRLR 31 an employee arranged with his employer to carry on the same work but to do it on a self- employed basis and a new agreement was drawn up. He paid tax under schedule D and self-employed National Insurance contributions which obviously benefited him, although there was no issue of trying to defraud the revenue. When he was later dismissed he tried to claim unfair dismissal but failed since he was in fact self- employed. The description in the new agreement accurately matched the relationship. In contrast in Young & Woods Ltd v West [1980] IRLR 201 a skilled sheet metal worker reached a similar agreement with his employer for tax purposes but the court held that the self- employed description did not match the reality of the situation. In all other respects the worker was an employee.

- ■ Level of independence – probably one of the most significant indicators that a person is self- employed is the extra degree of independence in being able to take work from whatever source and turn work down.

- ■ Another test could be to determine who has the benefit of any insurance cover that might be available (see British Telecommunications plc v James Thompson & Sons (Engineers) Ltd [1999] 1 WLR 9).

- ■ Another test could be to consider what any job advertisement or contract for the position states.

All of these are useful in identifying the status of the worker but none of them are an absolute test or are definitive on their own. As a result the 'multiple test' considers other factors.

The Privy Council in Lee v Chung and Shun Shing Construction & Engineering Co Ltd [1990] IRLR 236 also followed this approach and held that the fundamental issue was whether the person was performing services as a person in business on his own account. Factors that could be considered include:

- ■ the degree of risk the person takes;

- ■ the degree of responsibility for investment and management that the person has;

- ■ whether the person makes a profit;

- ■ whether the person hires people himself.

The approach was also developed in Hall (Inspector of Taxes) v Lorimer [1994] IRLR 171 where the Court of Appeal identified other factors that could be relevant:

- ■ the duration of the engagement;

- ■ the number of people by whom the individual is employed;

- ■ the degree of independence from the person paying the wages.

Not every factor will apply in every case. In Hall v Lorimer the court identified that rather than simply going through a checklist a detailed analysis of every situation should be considered in each case.

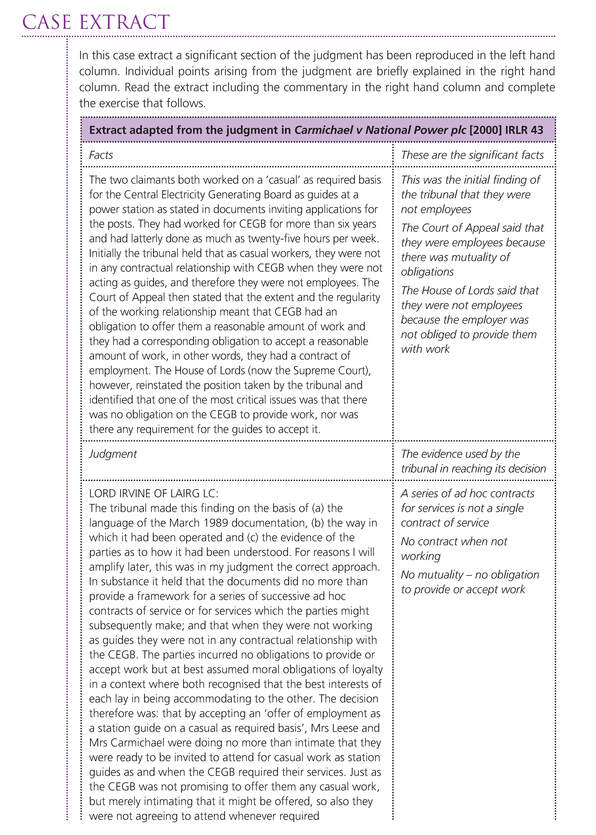

4.3.5 The mutuality of obligations test

Mutuality of obligations is a reasonably straightforward principle that has developed out of the multiple factor approach. The test identifies that for employment status there must be an obligation on the part of the employer to provide work for the employee and there must be a complimentary obligation on the part of the employee. Without these it is unlikely that a person could be classed as an employee.

Figure 4.4 Diagram illustrating the operation of the economic reality test

The test has developed out of disputes involving agency workers, casual staff and volunteers.

It follows that if a person is able to refuse work then their level of independence makes it unlikely that they can be considered to be an employee. In Carmichael v National Power plc [2000] IRLR 43 the House of Lords (now the Supreme Court) reinstated the view adopted by the tribunal that, as casual workers, the claimants were not in any contractual relationship with CEGB when they were not acting as guides, and they also failed the mutuality of obligations test so that therefore they were not employees.

Nevertheless, it is possible to infer mutuality from how the contract between the parties operates over a period of time.

Another aspect of mutuality of obligations is the requirement of personal service on the part of the worker. One of the factors that defeated the claimant in the Ready Mixed Concrete case was the fact that the new agreement identified that drivers could own more than one lorry and could use substitute drivers. So where the worker is not bound absolutely to perform the services personally but can substitute another person to carry out the work then the worker who can do that is much more likely to be self- employed because of the level of independence.

Figure 4.5 Diagram illustrating the operation of the mutuality of obligations test

Figure 4.6 Chart illustrating the relative merits of the four tests

4.4 Non-standard categories of work

In many if not most instances an employment relationship is straightforward. Certain types of work, however, are less clear cut and more likely to defy easy definition. This is why the tests in Chapter 4.3 have been developed. Over time judges and tribunal panels have been required to make decisions on employment status, sometimes based on the factors that have been identified above. Often the answer will depend on the purpose of the case. In this way the court might seek to bring a person within industrial safety law although they appear to be self- employed.

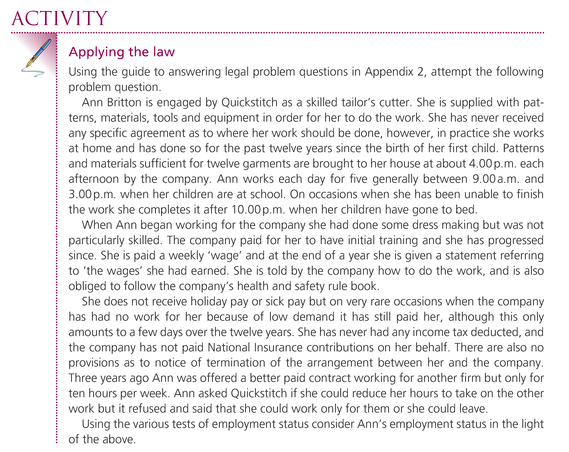

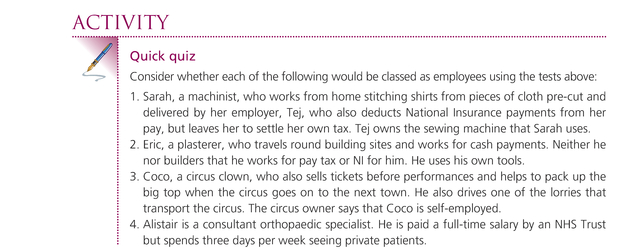

Outworkers

This group, sometimes also referred to as homeworkers, refers to people who work from home. They are usually women with young children and represent a disadvantaged sector of the workforce. They have traditionally tended to work for little pay and with few employment rights or protections. There is obviously little control over the hours that they work. Nevertheless, working in areas such as the garment industry, they normally fall into a general framework of organisation. They were in the past always considered to be independent contractors, which is well illustrated in the case law. However, some cases have suggested otherwise.

In such circumstances courts have identified that an umbrella contract can exist if a practice of dealing has been built up over years with expectations and obligations on each side. So it is because there is a mutuality of obligation that there is a contract of service rather than individual contracts for services.

Casual workers

Casual workers have traditionally been viewed as independent contractors rather than as employees. This may be of particular significance since modern employment practices tend towards less secure and less permanent work. It is obviously vital to consider all the relevant factors. In O’Kelly v Trust House Forte plc [1983] 3 WLR 605 (see 4.3.5 above) it was important for 'wine butlers', employed casually at the Grosvenor House Hotel, to show that they were employees in order that they could claim for unfair dismissal. They had no other source of income and they were able to show a number of factors consistent with employment. However, the tribunal took the view that, since there was no regular wage, sick pay or pension entitlement, the employer had no obligation to provide work and since they could if they wished work elsewhere then there was no mutuality of obligations and they were not employed.

One argument used in trying to establish that such workers are employees is that instead of there being a series of independent contracts that there is a global contract. However, without being able to show mutuality of obligations this has had little success.

In Carmichael v National Power plc [1998] ICR 1167 (see 4.3.5 above) the then House of Lords also confirmed that lack of mutual obligations in casual work will mean that the arrangement is unlikely to be seen as employment. While the tour guide at a nuclear power station was given work as required and paid for the work done and tax and National Insurance contributions were also deducted, the court decided that the critical factors were that there was no obligation to provide work and no obligation on the woman’s part to accept any that was offered.

However, there are still situations in which mutuality of obligations can be inferred from how the contract between the parties operates over a period of time. In Prater v Cornwall County Council [2006] IRLR 362 (see 4.3.5 above) the teacher had so many individual contracts over a period of ten years teaching excluded pupils from home that she was found to be an employee.

Agency staff

Many large companies now hire staff through employment agencies. The employer identifies to an agency posts that it needs filling. The agency generally has workers on its books with particular skills and can then send the required number of workers to the employer. On past cases they have not always been seen as employees either of the agency or of the business hiring their services. In Wickens v Champion Employment [1984] ICR 365 it was held that the agency workers were not employees since the agency was under no obligation to find them work and there was no continuity and care in the contractual relationship consistent with employment.

There is in fact a relatively confused situation with regard the employment status of agency workers and their employment status varies with the circumstances of the individual case. There are in any case three possibilities:

- ■ They are employees of the agency.

- ■ They are employees of the business hiring them from the agency.

- ■ They are not employees at all.

Clearly how the worker is defined in the contract with the employment agency is important but it is not absolutely definitive and it has been stated that there is no single factor that points to employment or self- employment: all of the relevant factors must be taken into account.

On the other hand courts applying the control test have often found that there is no employment relationship between the agency and the agency worker. In Montgomery v Johnson Underwood Ltd [2001] IRLR 269 the Court of Appeal held that an agency worker was not employed by the agency because she was not under its control while she was at work. Using the control test it has also been held that the agency worker is not an employee of the hirer or the agency.

It has also been held that an agency worker is not an employee, that he is hired out by the agency because there is no contractual connection between them.

On the other hand a contract of employment has been identified between the agency worker and the client hiring from the agency in circumstances where it can be shown that the agency worker has become integrated into the hirer's business.

Courts have also stated that whether an agency worker is an employee or not should be decided on the facts of the case and the principles of implied contracts rather than whether an irreducible minimum of obligations exists.

Workers’ co-operatives

Workers' co- operatives were quite common in the early 1980s after the government of the time had abandoned a lot of traditional industries that were run or supported by the state. Most of the mining industry disappeared during that time but steelworks, heavy engineering and other traditional industries were also affected. It was not unusual for groups of workers to collect together their redundancy payments and to buy the businesses for which they had worked and run them collectively with representatives of the workforce acting also as the management of these businesses. Again it is uncertain whether such workers would be employees or not. Usually we would expect them to be so. However, there are instances where such workers have been classed as an association of self-employed people.

Trainees

Because of the definition in section 230 Employment Rights Act 1996 (see 4.2.1 above) it is possible for an apprentice to be classed as an employee. However, apprenticeships were traditionally subject to their own distinct rules (although there are few of these traditional types of apprenticeship now in existence). In the case of trainees the major purpose in their relationship with the 'employer' is to learn their trade rather than to actually provide work. As a result there have been instances where they have not been classed as employees.

Crown servants

People working for the crown were traditionally viewed as not being under a contract of employment. This meant that they had very restricted rights. The trend in modern times has been to move away from this position. They may be classed as employees but may have more selective employment protection rights than other employees. Most of the provisions of the Employment Rights Act 1996 apply to Crown employees except those relating to notice periods and redundancy payments and there are restrictions on disclosure of information. They also fall under the provisions of the Equality Act 2010. They are also covered by most of the provisions in the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992.

Office holders

An office is basically a position that exists independently of the person currently holding it. The categories of people who can be classed as office holders are declining but it might include ministers of the church and justices of the peace as well as other offices. The picture on these is confused. Certainly they may have privileges not available to normal employees, an example being judges who hold office during good behaviour and can only be removed by a resolution passed by both Houses of Parliament. An office holder might in this sense have a greater job security than an ordinary employee would have.

Directors

A director may or may not also be an employee of the company. This will inevitably depend on the terms of the individual contract. In general an executive director is likely also to be an employee of the company. An executive director is one who is involved in the day- to-day running of the business. In the case of non- executive directors it is less likely that they will be regarded as employees. Non-executive directors are ones that usually only act in an advisory capacity.

Health service workers

One issue for people engaged in healthcare which could be critical was whether or not the health service employer was vicariously liable for torts committed by them during their work. The traditional view in Hillyer v Governor of St Bartholomews Hospital [1909] 2 KB 820 was that a hospital should not be vicariously liable for the work of doctors. Taking into account the age of the case the position was justified on the grounds that hospitals generally lacked adequate finance before the creation of the National Health Service. However, in Cassidy v Ministry of Health [1951] 2 KB 343 it was suggested that hospitals and health services should be responsible for the work done in them. A resident surgeon had performed an operation negligently and the patient sued. The issue for the court was whether the surgeon could be said legitimately to be under the employer's control because, if not, this would limit the patient’s ability to receive compensation. It was held that hospitals must inevitably be vicariously responsible for the tortious acts of all doctors who are permanent members of staff despite the difficulties associated with applying the traditional control test, since to do otherwise would generally be to deny wronged patients an effective claim.

In respect of employment rights and protections health service employees now have all of the rights in the legislation.

Police

While police officers are employed they have few employment rights. They are effectively excluded from most employment rights by section 200 of the Employment Rights Act 1996. These include for instance the right to an itemised pay statement, guarantee pay, rights under the Working Time Regulations, rights in protected disclosure situations, time off for public duties and many others. They are also excluded from unfair dismissal claims. However, they do have a full range of rights under the Equality Act 2010.

Probationary employees

Probationary employees by definition are serving a probationary period to establish their suitability for the post. They are aware from the start that their permanent employment is dependent on satisfactory completion of the probation.

One potential problem with probationers is the length of the probationary period. In Weston v University College Swansea [1975] IRLR 102 a lecturer was appointed for a probationary period of three years and then not given a permanent appointment. It was held that he was able to pursue an unfair dismissal claim.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn's Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 2.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 3.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 2.