13

Protection from discrimination (4) disability discrimination

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the background to disability discrimination in employment and its limitations prior to the Equality Act 2010

- ■ Understand the definition of disability under the Equality Act 2010

- ■ Understand the different types of prohibited practices under the Equality Act 2010 as they relate to disabled employees

- ■ Understand the nature and scope of the duty to make reasonable adjustments for disabled employees

- ■ Understand the processes for making claims for disability discrimination and the available remedies

- ■ Critically analyse the area

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

13.1 The origins of disability discrimination law

Disability discrimination is not in fact a new area of law. Rights for disabled employees were originally introduced as early as the Disabled Persons (Employment) Act 1944. However, the scope of this legislation was limited as were the rights gained under it. As a result it may actually have been of only quite marginal effectiveness to disabled employees.

The 1944 Act:

- ■ operated only in respect of employers who employed more than twenty employees - so many small businesses were in fact exempt from the provisions of the Act;

- ■ involved voluntary registration as a disabled person - this might not seem too onerous today when for instance we take great interest in the Paralympics but at the time there would have been a lot more stigma attached to disability than there is now;

- ■ imposed quotas on employers - 3 per cent of the workforce should be disabled - in reality there was only very limited monitoring, enforcement or indeed observance of the provision;

- ■ reserved certain occupations for the disabled.

The Act was ineffective, did little to actually advance employment opportunities for the disabled and was eventually repealed in the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. This Act was only introduced after a great deal of political ill will and following fourteen failed private member bills. In fact prior to the introduction of the Act there had been public criticism of the relevant minister by his own daughter who was also a campaigner for the disabled. The Act was a development from the previous law.

- ■ It provided a definition of disability in section 1 ‘a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial long term effect on ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities’ - although there was a restrictive list of affecting normal activities: ‘mobility, manual dexterity, co-ordination, continence, ability to lift or carry, speech, hearing, eyesight, memory, ability to learn or understand, perception of dangers’.

- ■ It provided some indications of what would amount to discrimination - although it made no provision for indirect discrimination.

- ■ It introduced in section 6 the duty to make reasonable adjustments to accommodate disabled workers.

However, like the previous Act, it had a number of limitations:

- ■ It only applied to employers with more than twenty employees - so provided no real opportunities for work with small sized enterprises which with the disintegration of large scale employment in the 1980s had expanded in proportion.

- ■ It covered only employees not the self-employed.

- ■ While the Act did create the National Disability Council this had none of the enforcement powers of the then Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) and Commission for Racial Equality (CRE).

- ■ The Act in any case was designed to come into force with the introduction of various regulations and this only happened slowly.

- ■ It did nothing to support employees with progressive illnesses in the initial stages of their illness.

- ■ In 2000 RADAR (a disability rights group) published a major report, ‘Mind the Gap’, which was very critical of the lack of support given in trying to move disabled people into work – it calculated that 2.8 million disabled people were on benefits at the time and further suggested that one million of those wanted to work and that 400,000 could enter work immediately if the major barriers were removed.

The Act has subsequently been replaced in the provisions relating to disability in the Equality Act 2010. This Act, which covers a wide range of areas of potential discrimination, resulted from the wide scale development of EU discrimination law in Framework Directive 2000/78.

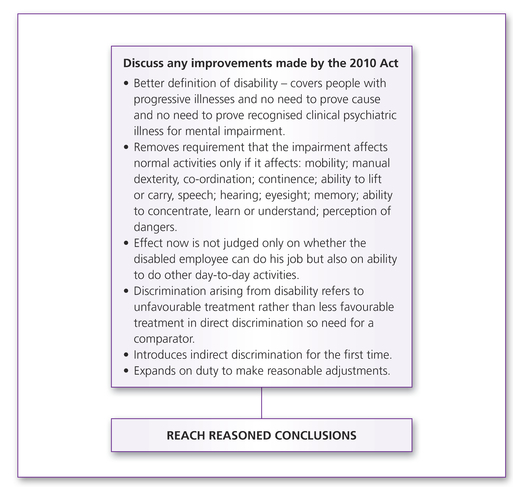

The Act introduces the idea of protected characteristics, disability being one, and prohibited conduct. It also incorporates specific requirements for the different protected characteristics. In the case of disability this has involved some changes from the previous law to the definition of disability; to the meaning of discrimination and also to the duty to make adjustments. While the case law under the previous law provides some useful illustration of the concepts, it is also possible that some will be overruled in new case law on the Act.

The Minister is empowered to introduce regulations on conditions proscribed as an impairment, the circumstances in which an effect is considered to be long term, what is considered to be a long term adverse effect, on progressive disability, when a person is considered to no longer have a disability, and can also give guidance on these matters.

There are now three key aspects concerning disability under the Act:

- ■ the definition of disability;

- ■ the types of prohibited behaviour;

- ■ the duty to make reasonable adjustments.

13.2 The Equality Act 2010 and the definition of disability

Introduction

The first requirement before a claim can be made for disability discrimination is that the employee is actually suffering from a disability. Disability is defined in section 6 as well as in schedule 1 of the Equality Act 2010.

It should be noted that the definition of disability for the purposes of the Equality Act are not necessarily the same as in other contexts, for instance for the purposes of claiming disability living allowance (DLA).

As a result of this definition there are three key aspects that need to be considered in any claim for disability discrimination:

- ■ the claimant has – a physical or mental impairment;

- ■ this impairment has – a substantial and long term adverse effect;

- ■ the effect is – on his ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

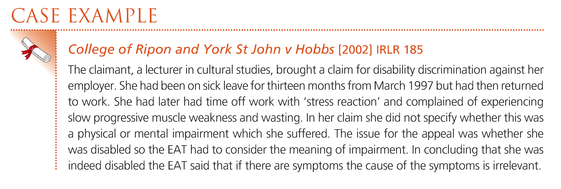

13.2.1 Physical or mental impairment

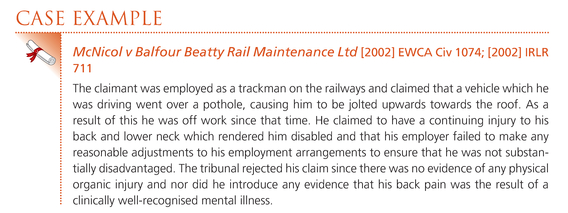

First and foremost to qualify as a disability under the Act there has to be a genuine impairment. The impairment can be either physical or mental. Traditionally under the 1995 Act where the claimant was arguing a mental impairment he was required to show that this resulted from a clinically recognised psychiatric illness.

Similarly in Goodwin v The Patent Office [1999] IRLR 4 the tribunal had concluded that the claimant who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and who was dismissed for bizarre behaviour did not suffer from a disability. The EAT disagreed and identified that in determining disability the World Health Organization (WHO) international classification of disease should be consulted. Cause was an issue since at that time the disability had to be caused by a clinically recognised illness. Now the presence of actual physical symptoms can be taken as evidence of an impairment without reference to any physical cause.

The cause of the impairment is not relevant as long as there are symptoms.

Impairment does not include addictions for example to drink, drugs or tobacco or other like substances. However, it could be that the impairment results from or is aggravated by such addictions.

Some other conditions such as kleptomania, pyromania, sexual deviancy, exhibitionism are not impairments. Seasonal conditions such as hay fever are not impairments but other conditions which they aggravate could be. Progressive illnesses such as multiple sclerosis and HIV which were not covered by the previous law now can be impairments so this is a significant improvement. HIV is now deemed to be a disability from the point of diagnosis according to the Schedules to the Act.

Even if the adverse effect from the impairment ceases it can still be classed as an impairment for the purposes of the Act if it is likely to recur.

13.2.2 A substantial or long term effect

A substantial long term effect means that the impairment has lasted for twelve months or is likely to last for more than twelve months or is likely to last for the rest of the disabled worker’s life.

There may also be a substantial adverse effect if:

- ■ measures are being taken to treat it or correct the impairment; and

- ■ but for those measures the impairment would be likely to have such an effect.

In assessing whether there is a substantial adverse effect the tribunal will only take into account what the person cannot do or can only do with difficulty, not what he can do.

However, in Woodrup v London Borough of Southwark [2003] IRLR 111 it was said that there was still a need to show there would be an adverse effect without the treatment. Here a claimant who suffered from a psychiatric disorder failed to show that withdrawal of psychotherapy would lead to a substantial adverse effect.

The substantial long term effect applies at the time of work not at the time of trial.

13.2.3 Normal day-to-day activities

Under the previous law there was a requirement that the impairment affects normal activities only if it affects: mobility, manual dexterity, coordination, continence, ability to lift or carry, speech, hearing, eyesight, memory, ability to concentrate, learn or understand, perception of dangers. This was a long but not exhaustive list and has not been included in the definitions in the Equality Act 2010. As a result the effect now is not judged only on whether the disabled employee can do his job. Inevitably this is relevant if the duties that the disabled employee engages can be seen as day-to-day activities.

In situations where the impairment fluctuates but is worsened by conditions at work it was identified in Cruickshank v VAW Motorcast Ltd [2002] IRLR 24 that whether the impairment has a substantial and long term effect should be assessed against day-to-day activities both at work and at home.

Normal day- to-day activities does not generally apply to specialist skills required in certain employment but can relate to activities found across a range of employment.

13.3 The Equality Act and the different types of discrimination

13.3.1 Discrimination arising from disability

By contrast to other protected characteristics where the employee is treated less favourably than a person not sharing their protected characteristic, in disability discrimination the reference is to unfavourable treatment so there is no need for a comparator. The definition of unfavourable treatment is in section 15 Equality Act 2010.

This is a significant development since under the previous law a lack of an appropriate comparator could defeat a claim. In London Borough of Lewisham v Malcolm [2008] UKHL 43 the claimant who suffered from schizophrenia was being evicted because he had moved out of his council flat and sublet it. It was held that the appropriate comparator was an able-bodied person who had done the same. Since the council would still have evicted them in the circumstances there was no discrimination. Section 15 effectively reverses the decision.

There are two strands to section 15:

- ■ the employer treats the disabled employee unfavourably because of something arising in consequence of the disability; and

- ■ this treatment cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

The change from treated less favourably (than an able-bodied comparator) to treated unfavourably obviously makes it easier to bring a claim, although there were instances in the previous law where courts interpreted the provision more liberally.

13.3.2 Direct discrimination

The definition of direct discrimination is straightforward and is found in section 13 Equality Act 2010.

So it would be direct discrimination where the employer treats the disabled employee less favourably because of his disability. This could be as simple as refusing to give the disabled person a job in the first place or for instance denying the disabled employee access to promotion purely because of the disability.

Section 13(3) also carries on to state that if the protected characteristic is disability, and B is not a disabled person, A does not discriminate against B only because A treats or would treat disabled persons more favourably than A treats B.

13.3.3 Indirect discrimination

This is an entirely new concept which was not present in the previous law under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. As a result there is not really much in the way of case law. The law is clearly going to be beneficial to disabled employees and this area of the Act is likely to be the subject of many claims and judicial interpretation in the coming years.

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.2 under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of their disability if:

- ■ he is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to his disability;

- ■ which applies to able-bodied and disabled employees but puts him at a disadvantage compared with able-bodied employees;

- ■ it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

In Farmiloe v Lane Group plc [2004] PIQR P22 the claimant was subjected to a health and safety requirement, to wear safety boots. Because of the nature of the work the practice would have applied to disabled and able-bodied employees alike. However, because of the psoriasis from which the claimant suffered it put him at a disadvantage. However, because the safety requirement was a legal obligation the requirement was a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

13.3.4 Harassment

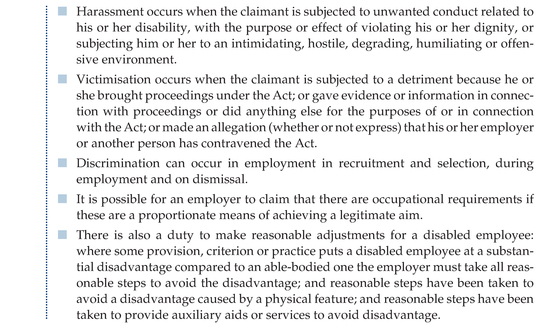

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.3 under section 26 Equality Act 2010 a person would suffer harassment because of disability if:

- ■ he was subjected to unwanted conduct related to his disability; and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his dignity, or subjecting him to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

13.3.5 Victimisation

Applying the full definition in Chapter 9.3.4 under section 27 Equality Act 2010 a person would have been victimised against because of his disability if:

- ■ he has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his employer or another person has contravened the Act.

13.3.6 Discrimination in employment

Applying the full definition from section 39(1) Equality Act 2010 an employer is not allowed to discriminate.

In selection and recruitment the discrimination could be:

- ■ in the way in which it decides who it will offer employment;

- ■ in the terms on which the employment is offered;

- ■ by not offering a person employment.

During employment discrimination could occur:

- ■ by giving the claimant poorer terms than that of an able-bodied employee;

- ■ in the way that it provides opportunities for promotion, transfer, training or any other benefit, service or facility;

- ■ by subjecting the claimant to any other detriment.

Discrimination could occur on dismissal:

- ■ when the employee is dismissed because of the disability.

Farmiloe v Lane Group plc [2004] PIQR P22 is an example of a dismissal which arose because of the employee’s disability, although of course it was justified because of the health and safety requirement.

Of course for section 39 to apply the claimant would have to be an employee (although the provisions under the Act apply not just to employees).

Occupational requirements (schedule 9) are not discriminatory if they are a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim and the disabled person does not meet the requirement

13.4 The duty to make reasonable adjustments

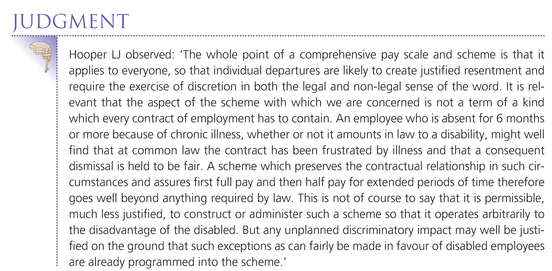

Inevitably there are many features that may make it difficult for a disabled employee to cope with the work environment. On this basis the Equality Act includes a duty to make reasonable adjustments, as did the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 before it. The duty to make reasonable adjustments is now found in section 20 Equality Act 2010.

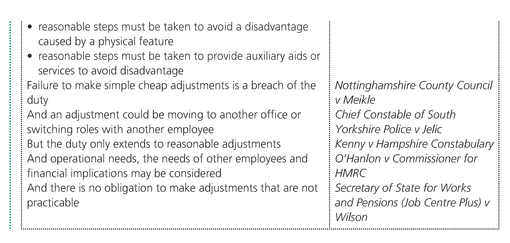

So there are three key aspects to the duty:

- ■ Where some provision, criterion or practice puts a disabled employee at a substantial disadvantage compared to an able-bodied one the employer must take all reasonable steps to avoid the disadvantage (so for example in the case of a rule that in the event of fire employees could not use lifts to evacuate the building, this would be a good rule because employees could end up being trapped in lifts in a fire with no means of exit, but it could also discriminate against employees in wheelchairs as well as visually impaired employees unless alternative measures were taken for their evacuation from the building).

- ■ Reasonable steps must be taken to avoid a disadvantage caused by a physical feature (so an obvious example here would be to ensure that all light switches are set low enough on walls for wheelchair users to reach them).

- ■ Reasonable steps must be taken to provide auxiliary aids or services to avoid disadvantage (so an obvious example of this would be the provision of disabled toilets).

It is discrimination if the employer fails to comply with any of these requirements and the duty is owed also to job applicants.

It will clearly be a breach of the duty where the adjustments are simple to make and involve no cost or burden to the employer.

Reasonable adjustments in any case can involve something as simple as moving the employer to a different department or part of the building or even swapping roles with another employee.

Further guidance on the second aspect of the duty, taking reasonable steps to avoid a disadvantage caused by a physical feature, is provided in sections 20(9) and 20(10).

This may require adapting premises, modifying equipment or providing specialist facilities, but the duty is only to make ‘reasonable’ adjustments. So it could involve providing a disabled toilet but not necessarily assistance in going to the toilet.

In assessing what is reasonable the operational needs of the employer as well as the needs of other employees may be taken into account as well as the nature of the activities involved, the size of the employer’s business and the financial implications of making the adjustment.

Figure 13.1 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of disability discrimination

An employer will also not be bound to make adjustments where the only adjustments that could be made are not practicable. In that instance the adjustments would not be reasonable adjustments to expect an employer to make.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 4.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 3.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 6.