21

Termination of employment (3) wrongful dismissal

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the nature of wrongful dismissal

- ■ Understand the circumstances in which an action for wrongful dismissal is likely to be brought

- ■ Understand the context in which wrongful dismissal claims are still relevant

- ■ Understand the process for masking wrongful dismissal claims

- ■ Understand the available remedies for a successful claim of wrongful dismissal

- ■ Critically analyse the concept of wrongful dismissal

- ■ Apply the rules on wrongful dismissal to factual situations

21.1 Introduction

Before 1971 an employer could, with few exceptions, in effect dismiss an employee for any reason or indeed for no reason. The law on dismissals at that time reflected the old ‘master and servant’ rules (see Chapter 1.4.1) and a court could not enquire into the fairness of a dismissal.

At that time one of the only issues on which the employee could challenge the dismissal was on whether the employer had dismissed the employee and prevented the employee from serving the appropriate notice under the contract or the remainder of a fixed-term contract. The action would be a simple breach of contract and the remedy represented the money that the employee should have been able to earn during the period of notice or the remainder of the fixed term. This was the action traditionally known as an action for wrongful dismissal.

The Industrial Relations Act 1971 (since repealed), although it was actually enacted more for the purpose of the statutory regulation of industrial relations, also created an action for unfair dismissal. This was also inserted in later Acts, most notably the Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act 1978, which has been replaced by the Employment Rights Act 1996 (as amended). An action for unfair dismissal is obviously now the most common course for employees to take to challenge a dismissal (see Chapter 22) and in many ways the pre-1971 law could be said to be of historical interest only. However, there are still some circumstances in which an action for unfair dismissal would be impossible or where an employee could gain a better remedy by using the old common law breach of contract action, and therefore wrongful dismissal remains a significant aspect of the law on dismissal in these limited circumstances.

21.2 The nature of wrongful dismissal

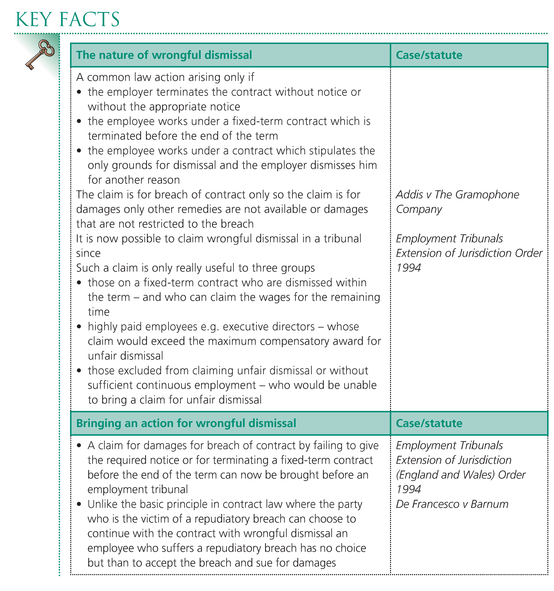

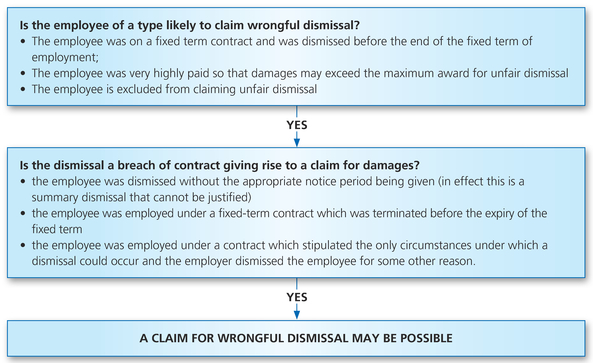

Traditionally there were three main situations in which a common law action for damages arising from a breach of contract might occur:

- ■ An employee was dismissed without the appropriate notice period being given (in effect this is a summary dismissal that cannot be justified).

- ■ An employee was employed under a fixed-term contract which was terminated before the expiry of the fixed term.

- ■ An employee was employed under a contract which stipulated the only circumstances under which a dismissal could occur and the employer dismissed the employee for some other reason.

So wrongful dismissal is an action for breach of contract and is concerned only with the form or manner of the dismissal and not in any way with the relative merits or fairness of the dismissal. This is of course quite different to unfair dismissal where there are a range of dismissals which are classed as automatically unfair and even where the dismissal falls into a category which is identified as potentially fair it is precisely the merits or fairness of the situation which are the critical elements in determining the outcome of the case.

Since the action is for damages which is restricted to damage stemming from the breach, in essence the notice period or remainder of a fixed term, there are likely to be few employees who would benefit from such a claim. For most employees the remedy is likely to be ineffective since their periods of notice would usually be so short that any damages payable would be minimal.

As a result an action for wrongful dismissal is likely to be significant for only three specific groups of workers:

- ■ Those on fixed-term contracts who have been dismissed before the end of the fixed term of employment.

- ■ Very highly paid employees such as executive directors where the statutory maximum for unfair dismissal may mean that they have more to gain from a breach of contract claim for wrongful dismissal – since 1 February 2013, the basic rate of compensation is £450 times the appropriate amount of service (see Chapter 22.7) and the ‘maximum compensatory amount’ is £74,200 – so the employee’s wages during the notice period would have to exceed this to make a wrongful dismissal claim worthwhile. It is apparent from news broadcasts that this could certainly be the case for example with chief executives of leading companies who are said to earn 145 times the average wage. It can also result from a very long notice period. In Clark v BET plc [1997] IRLR 348 for instance the notice period was three years.

- ■ Employees excluded from unfair dismissal claims – at the other end of the scale an employee who had insufficient continuous employment to claim unfair dismissal or who was ineligible might bring a wrongful dismissal claim although the damages are likely to be low, although better than nothing.

Wrongful dismissal is of course inconsistent with the basic rules of contract law. The employee has been dismissed so has no choice but than to accept the unlawful repudiation of the contract by the employer and try to claim compensation equivalent to the notice period.

In contrast in pure contract law a repudiatory breach of a condition would entitle the victim of breach the choice of what to do. He could either accept the breach and sue for damages or consider his own contractual obligations to be discharged in which case he can sue for damages but cannot be sued for failing to carry out his own obligations or he could continue with the contract if it was to his advantage. This could be the case with a unilateral variation of the contract by the employer where the employee continues to work but raises objections to the variation and makes it clear that he has not accepted the repudiatory breach (see Chapter 5.6.2). As usual the cards are in favour of employers contradicting the contractual base of a voluntary arrangement between two parties.

21.3 Bringing an action for wrongful dismissal

Up until July 1994 an action for wrongful dismissal had to be brought in a County Court or in the High Court. Before then tribunals had no jurisdiction to hear claims for a breach of a contract of employment. However, in July 1994 section 131 of the Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act 1978 (now section 3 of the Employment Tribunals Act 1996) was brought into force by the Employment Tribunals Extension of Jurisdiction (England and Wales) Order 1994, as a result of which a claim for damages for breach of contract by failing to give the required notice can now be brought before an employment tribunal. Now a claimant would have a choice of whichever was the more advantageous.

The employee must bring the claim within three months of the dismissal if the claim is to a tribunal. If the claim is brought in court then, because it is a breach of contract action, the claimant has six years in which to bring the claim.

21.4 Remedies for wrongful dismissal

Unlike unfair dismissal (see 22.7 below) there are no remedies of reinstatement or reengagement in wrongful dismissal since it is essentially a breach of contract action. Because of the reluctance of the courts to use other contractual remedies in contracts of personal service the main remedy is damages.

Damages

The amount of damages payable in a claim for wrongful dismissal is generally restricted to the amount of pay which would have been earned during the notice period the employee was entitled to or if it involves a fixed-term contract then this will be the pay for the remainder of the fixed term unless the contract allowed the parties to terminate before the end of the fixed term. In this case damages will be limited to whatever notice period was identified in the contract.

Sums that may also be included are any commission and overtime payments that would have been contractually due to be earned during the notice period. Loss of pension rights can also be calculated because a pension counts as wages.

The value of fringe benefits such as the use of a company car for private purposes can be claimed to the extent that these relate to the notice period which should have been given. The claim also can include the value of any rights to which the employee would have become entitled if the termination had been delayed until the end of a notice period. Subsidised mortgages, share options, private medical insurance can all be quantified and form part of the award of damages.

It is also possible in limited circumstances that the contract envisages a greater reward than basic salary by way of publicity and damages can reflect this with an award for loss of reputation arising from the breach of contract.

The same principle applied in Herbert Clayton & Jack Waller Ltd v Oliver [1930] AC 209 (see Chapter 7.2.2) where an actor who had been given a leading role was then placed in a minor role in the production. The employer was held to have breached the contract because of the potential impact on the actor’s reputation and future chances of work and the actor was awarded damages for the loss of opportunity that would result from his lowered reputation. It is unlikely, however, that this would occur other than in entertainment.

However, the courts will not award any damages in respect of the manner of the dismissal. So for instance there can be no general claim for injured reputation beyond the limited circumstances above.

As a development of this it has also been established that unfairness in the manner of the dismissal cannot form the basis of an action in either contract or tort.

However, a somewhat different view has subsequently been taken.

As with any contractual claim for damages an employee bringing an action for wrongful dismissal has a duty to take reasonable steps to mitigate his loss. In this case that will involve taking reasonable steps to find comparable work. This does not necessarily mean that the employee must accept any work regardless of how suitable or comparable. Although after a reasonable time the employee may have to be less selective. A refusal by the employee to accept other work may be unreasonable in the circumstances. In Brace v Calder [1895] 2 QB 253 following changes in the organisation of a partnership one of the partners was dismissed but then asked back by the new partners. When he refused he was only then entitled to nominal damages since he had failed to mitigate his loss. In contrast in Yetton v Eastwood Froy Ltd [1967] 1 WLR 104 a managing director was offered the position of assistant manager following his dismissal and it was held that this was a significant demotion so that his refusal to accept was not unreasonable.

The award of damages takes into account the tax and other contributions that the employee would have paid but under sections 401–404 Income Tax (Earnings and Pensions) Act 2003 the damages are not taxed unless they are more than £30,000.

Injunctions

The courts are reluctant to directly or indirectly enforce a contract of employment, sometimes referred to as the ‘rule against enforcement’, as the relationship is a highly personal one.

There are, however, some exceptions to the rule against enforcement:

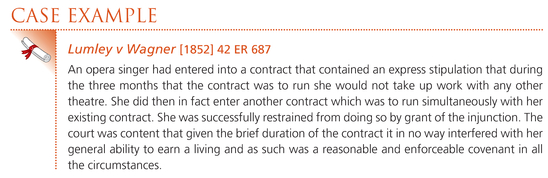

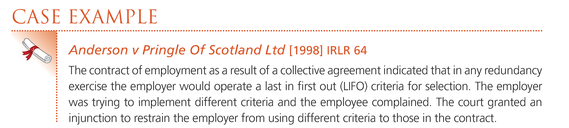

- ■ It is possible for a negative restraint clause to be included in a contract which a court will enforce where the employee has promised under the contract not to do certain things.

- ■ It is also possible that an injunction may be granted in circumstances where damages are an inadequate remedy following to the rule in Hill v Parsons.

- ■ The remedy is of course equitable and therefore is the discretion of the court. One of the problems that judges have to consider in allowing injunctions in employment matters is that they are similar in effect to specific performance.

Figure 21.1 Flow chart illustrating the necessary elements for a claim for wrongful dismissal

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 16.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 8, pp. 339–360.

Sargeant, Malcolm and Lewis, David, Employment Law 6th edition. Pearson, 2012, Chapter 4.3.