14

Protection from discrimination (5) recent developments in discrimination law

Aims and Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- ■ Understand the background to discrimination in employment and its limitations prior to the Equality Act 2010

- ■ Understand the protected characteristics of sexual orientation, gender reassignment, religion and belief, and age

- ■ Understand the different types of discrimination identified as prohibited conduct in the 2010 Act and how they apply

- ■ Understand how an occupational requirement might apply in each case

- ■ Understand the protections available to part-time employees, employees on fixed-term contracts and agency workers

- ■ Critically analyse the area

- ■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

14.1 The background to the wider development of discrimination law

Law on sex and race discrimination and to a lesser extent disability discrimination were well established in English law before the Framework Directive 2000/78 and the Race Directive 2000/43. The Framework Directive 2000/78 as a part of the social policies of the EU has significantly widened the scope of discrimination law by applying it to a wider range of characteristics, including now sexual orientation, gender reassignment, religion and belief, and age. All of these are now protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010 and protected against different types of prohibited conduct identified in the Act. These four areas are considered in sections 14.2–4.5 below.

Sections 14.6–14.8 concern types of work rather than characteristics of the individual worker, part-time workers, fixed-term employees and agency workers. These are all areas where there was traditionally little if any legal protection and therefore ideal ways of employing workers while avoiding the obligations that employers would owe towards their workforce in a straightforward employment relationship. Again the significant feature characterising the development of employment protections in these areas is that it has been driven by EU directives. The significance of membership of the EU to protection against discrimination then cannot be exaggerated.

14.2 Sexual orientation

Traditionally there was no law protecting a person from discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation. It was not covered in the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 or in the Equal Treatment Directive 76/207.

Sexual orientation was introduced in EU law in the Framework Directive 2000/78 and therefore required implementation into the law of Member States. In the UK this came in the Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003. Prior to the introduction of the Regulations there were attempts to bring claims using the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and the then Equal Treatment Directive 76/207.

The attitude of the courts was that the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 did not cover sexual orientation and neither did the then Equal Treatment Directive 76/207.

It was also the case that the ECJ at that time failed to identify that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation fell within the scope of EU (then EC) law.

This then influences the view taken by the Court of Appeal in Smith v Gardner Merchant Ltd [1999] ICR 134 of who the comparator is when a claim under sex discrimination involves a gay person.

EU law in the shape of the Framework Directive 2000/78 first introduced sexual orientation as an area that could be protected from discrimination. The UK implemented the directive in the Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003 which covered the four types of discrimination, direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation. The actual sexual orientation of a claimant is not necessarily relevant to a claim.

Sexual orientation is now a protected characteristic under section 4 of the Equality Act 2010. Section 12 defines who is included within this protected characteristic.

Prohibited conduct

All four types of prohibited conduct apply to the protected characteristic of sexual orientation.

In the case of direct discrimination, under section 13 Equality Act 2010 a person would be directly discriminated against because of their sexual orientation if he or she is treated less favourably than a person of a different sexual orientation would be. It could also be because of their perceived sexual orientation or because they associate with gay people.

In the case of indirect discrimination under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of sexual orientation if:

- ■ he is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to sexual orientation;

- ■ which applies to any sexual orientation but it puts him or her at a disadvantage;

- ■ and it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

A claim for harassment is also possible which under section 26 Equality Act 2010 would occur if a person:

- ■ was subjected to unwanted conduct related to his or her sexual orientation, and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his or her dignity, or subjecting him or her to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

A claim of victimisation is also possible under section 27 Equality Act 2010 if the person:

- ■ has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his employer or another person has contravened the Act.

Discrimination in employment

Sexual orientation is also covered by section 39 Equality Act 2010 so a complaint can be made concerning discrimination in the context of employment. Clearly discrimination might occur in employment:

- ■ in selection and recruitment – the way in which the employer decides who it will offer employment, in the terms on which the employment is offered or by not offering a person employment because of their sexual orientation; or

- ■ during employment – by giving the claimant poorer terms than that of an employee of a different sexual orientation, or in access to opportunities for promotion, transfer, training or any other benefit, service or facility, or by subjecting the claimant to any other detriment because of his or her sexual orientation;

- ■ on dismissal if this is because of the person’s sexual orientation.

It is also possible that there could be an occupational requirement. One would be where the nature of the employment is such that requiring a person of a particular sexual orientation is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. A second is where there is a requirement of a particular sexual orientation to comply with specific religious doctrines. This was what was being argued in Reaney v Hereford Diocesan Board of Finance [2007] ET 1602844 above. The requirement to abstain from sexual behaviour was to comply with the doctrines of the Church of England and it was also to avoid conflict with the strongly held religious convictions of a significant number of the religion’s followers. However, the tribunal held that the bishop had not been reasonable when he did not believe that the claimant could meet the requirement which was why the occupational requirement defence was not available.

Figure 14.1 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation

14.3 Gender reassignment

Traditionally there was no protection against discrimination for transsexuals, people undergoing medical processes to change their original biological sex. In fact the original law was that the person retained the same sex in law regardless of whether they had gone through gender reassignment. This seemed quite unjust in the case of the most ambiguous instances of hermaphroditism. Another consequence of the law of course was that those who had undergone gender reassignment would be unable to marry.

There were cases where courts or tribunals had to consider the issue.

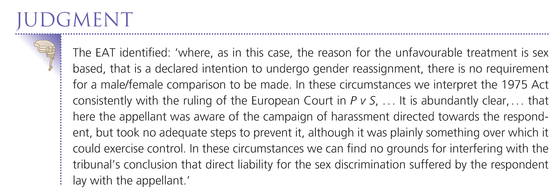

In later cases the EAT accepted that the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 could apply to discrimination on the basis of a person’s gender reassignment.

Parliament inserted protection in the case of gender reassignment in the Sex Discrimination (Gender Reassignment) Regulations 1999. The EU Framework Directive 2000/78 introduced a number of areas requiring the protection of anti-discrimination legislation including gender reassignment. The UK subsequently passed the Gender Reassignment Act 2004. As a result of the Act transsexuals are able to marry in their acquired gender and can also have an updated birth certificate. In Chief Constable of Yorkshire v A [2005] AC 51 it was held that under the 2004 Act once a person has undergone gender reassignment and gained formal recognition under the Act they are entitled to be treated as a person of the acquired gender.

Gender reassignment is now a protected characteristic under section 4 of the Equality Act 2010. Section 7 defines who is included within this protected characteristic.

Prohibited conduct

All four types of prohibited behaviour apply – direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation – as does section 39 on discrimination in employment.

In the case of direct discrimination, under section 13 Equality Act 2010 a person would be directly discriminated against if he or she is treated less favourably because of undergoing gender reassignment within the meaning given in section 7. P v S and Cornwall CC [1996] IRLR 347 above is an obvious case of direct discrimination involving a discriminatory dismissal.

In the case of indirect discrimination under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of undergoing gender reassignment if:

- ■ he is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to gender reassignment;

- ■ which applies regardless of gender reassignment but it puts him or her at a disadvantage;

- ■ and it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

A claim for harassment is also possible which under section 26 Equality Act 2010 would occur if a person:

- ■ was subjected to unwanted conduct related to his or her gender reassignment; and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his or her dignity, or subjecting him or her to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

Chessington World of Adventure v Reed [1997] IRLR 556 is a case of harassment and also involves a discriminatory dismissal.

A claim of victimisation is also possible under section 27 Equality Act 2010 if the person:

- ■ has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his employer or another person has contravened the Act.

Discrimination in employment

Gender reassignment is also covered by section 39 Equality Act 2010 so a complaint can be made concerning discrimination in the context of employment. Clearly discrimination might occur in employment:

- ■ in selection and recruitment – the way in which the employer decides who it will offer employment, in the terms on which the employment is offered or by not offering a person employment because of their gender reassignment; or

- ■ during employment – by giving the claimant poorer terms than that of an employee of the opposite sex to the person’s acquired sex or in access to opportunities for promotion, transfer, training or any other benefit, service or facility, or by subjecting the claimant to any other detriment because of his or her gender reassignment;

- ■ on dismissal if this is because of the person’s gender reassignment.

An occupational requirement under schedule 9 is also possible. The requirement would obviously have to be as proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

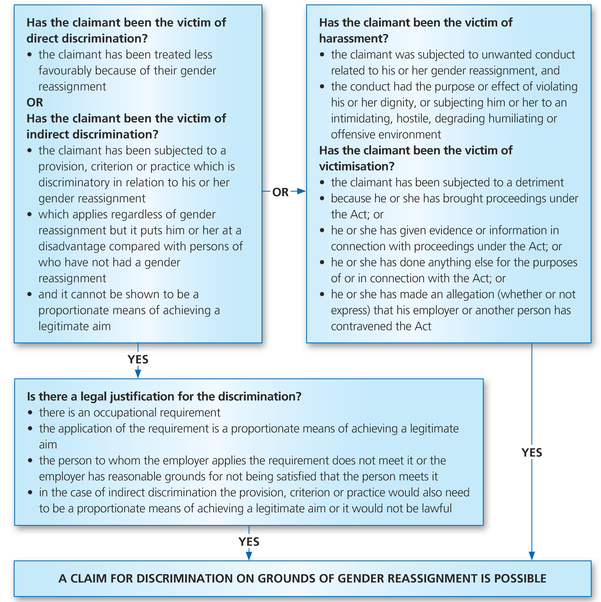

Figure 14.2 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of discrimination on grounds of gender reassignment

14.4 Religion and belief

Traditionally there was no law protecting a person from discrimination on the basis of their belief. We have seen this in Chapter 12.2 where in Mandla v Dowell Lee [1983] 2 AC 548 the Court of Appeal held that Sikhs were not an ethnic group but a religious group and therefore not covered by discrimination law, although the then House of Lords reversed this. Similarly in Seide v Gillette Industries [1980] IRLR 427 Jews were protected because they were seen as a distinct ethnic group as well as a religious one. In contrast Muslims were assumed not to be a distinct ethnic group in Walker v Hussain [1996] IRLR 11 and were therefore not covered by discrimination law. Similarly Rastafarians have also been considered not to be a distinct ethnic group. Also in Dawkins v Crown Suppliers (PSA) [1993] ICR 517 Rastafarians were held to be a religious cult preventing the claimant from relying on discrimination law.

Religion and belief was introduced in EU law in the Framework Directive 2000/78 and therefore required implementation into the law of Member States. In the UK this came in the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief ) Regulations 2003.

Religion and belief is now a protected characteristic under section 4 of the Equality Act 2010. Section 10 defines who is included within this protected characteristic.

The meaning of religion or belief

Clearly the definition is broad enough to cover all religions and indeed section 10(2) shows that it can cover atheism also. All of the established religions should fall within the definition even fringe ones. In Harris v NLK Automotive Ltd and Matrix Consultancy UK Ltd [2007] UKEAT 0134 07 0310 held that Rastafarianism could be classed as a philosophical belief for the purposes of the 2003 Regulations. Similarly in Power v Greater Manchester Police [2009] UKEAT 0087 10 0810 spiritualism was also held to be a philosophical belief.

Nevertheless, the meaning of ‘philosophical belief ’ might create greater difficulty for interpretation.

Prohibited conduct

All four types of prohibited conduct apply to the protected characteristic of religion and belief.

In the case of direct discrimination, under section 13 Equality Act 2010 a person would be directly discriminated against because of their religion or belief if he is treated less favourably than a person of a different religion or belief would be.

In the case of indirect discrimination under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of his religion or belief if:

- ■ he is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to his religion or beliefs;

- ■ which applies regardless of religion or belief but it puts him at a disadvantage compared with persons of a different religion or belief (which could include no religion or belief );

- ■ and it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

In Azmi v Kirklees Metropolitan Borough Council [2007] IRLR 484 indirect discrimination was also alleged. However, this argument also failed since the requirement that the teacher show her face to her pupils was a necessary and proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim in that children of such a young age should have a full facial view of their teachers otherwise it would restrict signals that the children might otherwise get from her.

The issue obviously concerns religious symbolism or outward manifestations or belief. For there to be discrimination in this sense the religious symbol would have to be a mandatory requirement of the religion.

A claim for harassment is also possible which under section 26 Equality Act 2010 would occur if a person:

- ■ was subjected to unwanted conduct related to his religion or belief; and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his dignity, or subjecting him to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

A claim of victimisation is also possible under section 27 Equality Act 2010 if the person:

- ■ has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his employer or another person has contravened the Act.

Discrimination in employment

Religion and belief is also covered by section 39 Equality Act 2010 so a complaint can be made concerning discrimination in the context of employment. Clearly discrimination might occur in employment:

- ■ in selection and recruitment – the way in which the employer decides who it will offer employment, in the terms on which the employment is offered or by not offering a person employment because of their religion or belief; or

- ■ during employment – by giving the claimant poorer terms than that of an employee of a different religion or belief, or in access to opportunities for promotion, transfer, training or any other benefit, service or facility, or by subjecting the claimant to any other detriment because of his religion or belief;

- ■ on dismissal if this is because of the person’s religion or belief.

In selection and recruitment clearly this could be an issue where the employer provides a service that is in some way faith led. If the refusal to employ cannot be justified then it may be discriminatory.

In the case of discrimination during employment this was the context of both Azmi v Kirklees Metropolitan Borough Council [2007] IRLR 484 and Eweida v British Airways [2010] IRLR 322. Both would have argued that they were subjected to a detriment because of their religion or belief, but both failed for the reasons given above.

Any detriment because of the claimant’s religion or belief would clearly also be discriminatory. However, the detriment must have resulted from the religion or belief of the claimant and not for any other reason.

A dismissal purely based on the claimant’s religion or belief would clearly also be discriminatory. However, the dismissal must have resulted from the religion or belief of the claimant and not for any other reason.

Occupational requirement

Religion and belief is covered by the occupational requirement in schedule 9 Equality Act 2010 so an employer may be able to justify alleged discrimination on the ground of religion or belief if:

- ■ there is an occupational requirement; and

- ■ the application of the requirement is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim; and

- ■ the person to whom the employer applies the requirement does not meet it or the employer has reasonable grounds for not being satisfied that the person meets it.

In Glasgow City Council v McNab [2007] IRLR 476 above the local authority was claiming that the requirement for employees to be Catholic which had prevented them from interviewing the claimant for the post of Principal Teacher in Pastoral Care was a genuine occupational requirement. The EAT held that, while the school was a faith school it was not a necessary requirement that the teacher should be of Catholic faith. There was no occupational requirement in the circumstances and the school’s actions were unlawful discrimination. Of course had he been applying for the post of say RE teacher, then the decision may well have been different.

Figure 14.3 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of discrimination on grounds of religion or belief

14.5 Age

Traditionally there was very little in the way of protection from discrimination on grounds of age. It is true that the earliest industrial safety law, the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, was passed to protect child workers and such reforms continued throughout the nineteenth century (see Chapter 1.2.3 and 1.3). Protection from exploitation of children through statute has continued. However, age discrimination can occur in many ways.

Inevitably, while discrimination could occur at all ages probably the most discriminated against are the young and the aged. Age discrimination clearly has the potential to be a significant issue in employment. Government statistics show that youth unemployment is currently running at above 20 per cent and the educational reforms and increase in fees is likely to lead to a decrease in the numbers of students in both further and higher education in the next few years which may well show up a bigger problem in youth unemployment. There is also a growing aged population. The Office of National Statistics suggests that by 2020 the proportion of the workforce that is over fifty will have risen to one-third. That there is no longer any default retirement age is likely to mean that people stay in work longer and young people may have even greater difficulty in finding work.

Age was introduced in EU law in the Framework Directive 2000/78 and therefore required implementation into the law of Member States. In the UK this came in the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006. The Regulations followed the Framework Directive and introduced the usual areas of direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation. They also removed the upper age limits for unfair dismissal claims and redundancy, provided exemptions from some aged based rules in occupational pensions, and the upper age limits for statutory sick pay.

Age is now a protected characteristic under section 4 of the Equality Act 2010. Section 5 defines who is included within this protected characteristic.

Prohibited conduct

All four types of prohibited conduct apply to the protected characteristic of age.

In the case of direct discrimination, under section 13 Equality Act 2010 a person would be directly discriminated against because of his age if he is treated less favourably than a person of a different age would be.

Direct discrimination is clearly problematic in situations like that above where an employee in that age group may find it difficult to find another job because of his age. It is of course a significant problem at the other end of the age spectrum where a young person is dependent on gaining or continuing in employment in order to progress.

In the case of indirect discrimination under section 19 Equality Act 2010 a person would be indirectly discriminated against because of his age if:

- ■ he is subjected to a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory in relation to his age;

- ■ which applies to any age group but it puts him at a disadvantage compared with persons of a different age;

- ■ and it cannot be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

As is the case with other protected characteristics indirect discrimination is really concerned with disguised age which put a person at a disadvantage because of their age. The question for the court is whether or not this can be justified.

A claim for harassment is also possible which under section 26 Equality Act 2010 would occur if a person:

- ■ was subjected to unwanted conduct related to his age; and

- ■ the conduct had the purpose or effect of violating his dignity, or subjecting him to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

A claim of victimisation is also possible under section 27 Equality Act 2010 if the person:

- ■ has been subjected to a detriment;

- ■ because he has brought proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has given evidence or information in connection with proceedings under the Act; or

- ■ he has done anything else for the purposes of or in connection with the Act; or

- ■ he has made an allegation (whether or not express) that his employer or another person has contravened the Act.

Discrimination in employment

Age is also covered by section 39 Equality Act 2010 so a complaint can be made concerning discrimination in the context of employment. Clearly discrimination might occur in employment:

- ■ in selection and recruitment – the way in which the employer decides who it will offer employment, in the terms on which the employment is offered, or by not offering a person employment because of their age; or

- ■ during employment – by giving the claimant poorer terms than that of an employee of a different age, or in access to opportunities for promotion, transfer, training or any other benefit, service or facility, or by subjecting the claimant to any other detriment because of his age;

- ■ on dismissal if this is because of the person’s age.

Homer v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police [2012] UKSC 16 above is an obvious example of age discrimination during employment. London Borough of Tower Hamlets v Wooster [2009] IRLR 980 above is an obvious example of a discriminatory dismissal on the basis of age.

The occupational requirements under schedule 9 also apply if they are a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. This is an area that has been the subject of some discussion by the ECJ.

Retirement age

From 1 October 2011 the default retirement age of sixty-five was repealed as a result of the Employment Equality (Repeal of Retirement Age Provisions) Regulations 2011. An employer then has the choice either to abolish fixed retirement ages altogether in his organisation or to keep a fixed retirement age. If he does keep a fixed retirement age then this will need to be objectively justified. Objective justification means that the employer must show that the retirement age is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. There will need to be a sound business reason for the retirement age chosen and the employer will have to produce evidence to show this. Now employees have the choice about whether to retire or not.

14.6 Part-time workers

It is not that long ago in the past that part-time workers had very little in the way of rights. At one time a person working less than eight hours per week had no employment protections and a person working less than sixteen hours per week had very little employment protection.

Protection from discrimination against part-time employees is essential when it is remembered that the majority of part-timers are women and therefore it is a double discrimination. Since the 1980s part-time work has increased dramatically to more than a quarter of the workforce. The significance of this is that more than 40 per cent of part-time employees are women. The significance of the lack of proper protection against part-time employees and the effect on women was recognised in R v Secretary of State, ex parte Equal Opportunities Commission [1994] IRLR 176 where the then House of Lords (now the Supreme Court) held that the provisions of the then Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act 1978 (replaced by the Employment Rights Act 1996) under which employees working for under sixteen hours per week were subject to different conditions in qualification for redundancy pay from those applying to employees working more than sixteen hours per week were incompatible with Article 119 EC Treaty (now Article 157 TFEU).

The issue of the treatment of part-time employees had already been considered by the ECJ in a referral from the English courts in a case concerning an equal pay claim.

Figure 14.4 Flow chart illustrating the requirements for a claim of age discrimination

The ECJ had also developed the criteria for objective justification for differential treatment in Bilka Kaufhaus GmbH v Weber von Hartz [1987] ICR 110 that:

- ■ The measure must correspond to a genuine need of the business.

- ■ It must be suitable for obtaining the objective.

- ■ It must be necessary for that purpose.

The Employment Protection (Part-time Employees) Regulations 1995 were introduced and these removed some of the unequal treatment of part-time employees. However, the significant step towards equal treatment came in the EC (now EU) Directive on Part-time Working 97/81 which resulted from the EC Framework agreement on part-time working. The Directive provided for the removal of discrimination against part-time workers and aimed to improve the quality of part-time work.

The directive has been implemented in the UK in the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000 (as amended). The definitions of part-time worker and full-time worker are found in section 2(2) of the Regulations.

So the definition is quite broad which is not surprising since it derives from EU law. A part-time employee is in essence any worker whose pay is determined by the hours that he works and these are less than a full-time employee. As a result the definition only excludes the genuinely self-employed who would be in a business relationship with the person hiring their services.

As a result of the definition in section 2 the part-time employee will have to find a full-time comparator. The identity of the comparator is explained in section 4.

The test is obviously quite demanding and requires an actual comparator and not a hypothetical one.

The right not to be subjected to less favourable treatment is found in section 5 of the Regulations.

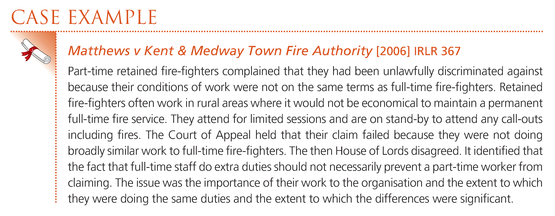

To bring a claim the part-time worker must show that he works for the same employer as a full-time worker doing broadly similar work and that he has less favourable conditions of work by comparison or is suffering a detriment because of being a part-time worker.

Under Regulation 5 a part-time worker is entitled to the same terms and conditions as a full-time worker who is doing broadly the same work. This means that a pro rata principle must be applied and the part-time worker should be paid at the same rate as the full-time worker in proportion to the hours worked. An exception to this principle is overtime. If the employer does not pay overtime to the part-time worker until he has worked the same hours as a full-time worker then this will not amount to less favourable treatment.

In Sharma v Manchester City Council [2008] IRLR 236 the EAT also identified that the fact that the claimant works part-time need not be the only reason for the different treatment for there to be a claim.

Regulation 7 also makes it an unfair dismissal if the claimant’s dismissal is connected with his rights under the Regulations (see Chapter 22.3).

Where an employee claims under the Regulations there may initially be a hearing with ACAS. In a successful claim a tribunal can award compensation and make recommendations for the employer to remove the discrimination.

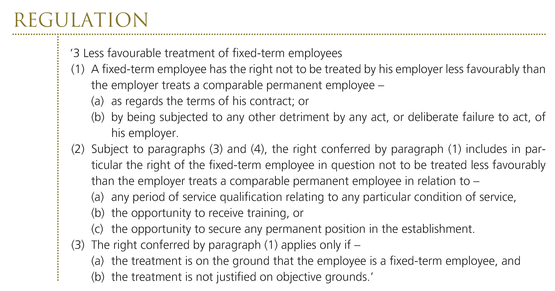

14.7 Fixed-term workers

Fixed-term contracts also account for a significant proportion of the workforce. Inevitably people will be prepared to accept a fixed-term contract rather than have no employment at all. It is unlikely in most cases that a person would subject himself to the limited security of a fixed-term contract if an alternative permanent arrangement was available. EU Directive 99/70 concerning the framework agreement on fixed-term work was eventually passed after a lengthy period of trying to persuade Member States, the first proposal having been in 1990.

The purpose of the directive was to:

- ■ improve the quality of fixed-term work by ensuring non-discrimination;

- ■ establish a framework to prevent abuses arising from the use of fixed-term contracts.

A fixed-term employee is one where the termination of the contract of employment is predetermined by objective conditions such as reaching a specific date, completing a specific task or the occurrence of a specific event. So for instance a football manager might be hired by a football club for three years, or an oilfield surveyor might be hired by an oil company only up until such time as the company has struck oil in a particular oilfield.

The directive was initially partly implemented in the Employment Relations Act 1999 which effectively brought fixed-term contracts within the scope of unfair dismissal. Subsequently the directive was implemented in the Fixed Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002.

The definition of fixed-term worker is very similar to that of part-time worker and is in Regulation 2.

Figure 14.5 Flow chart illustrating the elements of possible claims under the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000

So again a comparator will be a person with a contract of employment of indeterminate length who works for the same employer at the same establishment or another of the employer’s establishments. The distinction from the regulations on part-time workers is that the regulations covering fixed-term contracts apply only to employees. This is likely to exclude large numbers of workers from the protection from discrimination.

The definition of less favourable treatment is in Regulation 3.

This means comparable treatment in pay, pensions, statutory sick pay, guarantee payments and medical suspension payments. As is identified in Regulation 3(3)(b) differential treatment of fixed-term employees is only possible if it is objectively justified. This defence is identified in Regulation 4.

In the same way as with part-time workers a dismissal that is connected to the rights a fixed-term employee gains under the Regulations will be an automatically unfair dismissal. Regulation 6 on unfair dismissal is phrased in the same terms as Regulation 7 of the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000. Again a tribunal can award compensation and make a recommendation for the employer to end the discrimination.

Where there are a series of fixed-term contracts Regulation 8 identifies that if the fixed terms are continually renewed for four years then the contract automatically becomes a permanent contract unless there is an objective justification for the contract not being permanent. However, an employer only has to have a break between successive fixed terms to break continuity of employment and this could make the Regulation ineffective.

14.8 Agency workers

The traditional problem with agency workers is that it depends on the circumstances of each case whether they will be classed as employees (see Chapter 4.4). Therefore traditionally they have generally lacked any employment protections even though, by government figures in 2009 there were estimated to be more than 1.3 million. There are now protections against discrimination in the Agency Workers Regulations 2010. The Regulations only apply to workers who are supplied by a temporary work agency. Workers who are supplied to an employer by an employment agency are not protected by the Regulations since by definition they are seeking to find permanent employment for the people who enlist with them. Regulation 3 identifies in detail which workers come under the Regulations.

There is another significant limitation on which workers can gain the protection from discrimination in the Regulations, a qualifying period of continuous service. This limitation is identified in Regulation 7.

Regulation 5 provides that the temporary agency worker is entitled to the same conditions as he would have had if he had been hired directly by the hirer rather than through an agency. On which basis the comparator is a person employed by the hirer doing the same or broadly similar work as the temporary agency worker.

The terms and conditions of employment falling under the basic right in Regulation 5 are identified in Regulation 6 and include pay, the duration of working time, night work, rest periods, rest breaks and annual leave.

Under Regulation 6(2) pay means ‘any sums payable to a worker of the hirer in connection with the worker’s employment, including any fee, bonus, commission, holiday pay or other emolument referable to the employment, whether payable under contract or otherwise, but excluding’ a number of possible payments including occupational sick pay, pension, any payment in respect of maternity, paternity or adoption leave, redundancy and guarantee payments.

In the same way as with part-time workers and fixed-term employees a dismissal that is connected to the rights of an agency worker gains under the Regulations will be an automatically unfair dismissal. Regulation 17 on unfair dismissal is phrased in the same terms as Regulation 7 of the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000 and Regulation 6 in the Fixed Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002. Again a tribunal can award compensation and make a recommendation for the employer to end the discrimination.

Further reading

Emir, Astra, Selwyn’s Law of Employment 17th edition. Oxford University Press, 2012, Chapter 4.

Pitt, Gwyneth, Cases and Materials on Employment Law 3rd edition. Pearson, 2008, Chapter 3.