In this chapter, you will learn about. . .

Human Resources and Quality Management

The Changing Nature of Human Resources Management

Contemporary Trends in Human Resources Management

Employee Compensation

Managing Diversity in the Workplace

Job Design

Job Analysis

Learning Curves

Web resources for this chapter include

OM Tools Software

Animated Demo Problems

Internet Exercises

Online Practice Quizzes

Lecture Slides in PowerPoint

Virtual Tours

Excel Exhibits

Company and Resource Weblinks

www.wiley.com/college/russell

Human Resources AT HERSHEY'S

Hershey's is committed to a diverse and all-inclusive workforce. The company provides a variety of opportunities for its employees to learn and grow in the work environment and the community. Hershey's sponsors Diversity Councils and Affinity Groups that provide forums for employees to make and discuss recommendations on increasing productivity and improving the quality of the work environment. These include the Asian Affinity Group, the African American Affinity Group, and the Hispanic Affinity Group, that foster an environment of support, and cultural and personal growth and development, aimed at making Hershey's the employer of choice for these groups. Prism, a resource for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender employees, seeks to improve the quality of the work environment for all Hershey's employees. The Women's Council promotes and facilitates positive change related to women's issues through networking, work/life programs, and employee education, with a goal of making Hershey's one of the top 100 employers of choice for talented women. The Sales Diversity Council promotes advancements in diversity and inclusion across all levels of the sales organization. Hershey's also holds an annual company-wide Inclusion Day celebrating the diversity of local communities. Lunch and Learn speakers discuss such topics as new immigrant experiences and personal empowerment for women and minorities. An in-depth company Web site provides employees with information about an array of diversity subjects. Diversity email newsletters educate employees on specific aspects of diversity and about why these differences are important to Hershey's. All of these efforts at Hershey's are aimed at helping the company realize its vision of "Great People Building Great Brands."

In this chapter we will discuss the basic principles and recent trends of human resource management that successful, quality-focused companies like Hershey's follow to develop a motivated, skilled, and satisfied workforce.

Source: The Hershey's Company Web site at www.thehersheycompany.com

Employees—the people who work in an organization—are "resources," as important as other company resources, such as natural resources and technology. In fact, it is the one resource that all companies have available to them. A company in Taiwan, Japan, or Denmark may have different and few natural resources, certainly fewer than U.S. companies have, but they all have people. With the same or superior technologies as their competitors, and with good people, foreign companies can compete and thrive. Increasingly, skilled human resources are the difference between successfully competing or failing.

The traditional view of employees or labor was not so much as a valuable resource, but as a replaceable part of the productive process that must be closely directed and controlled. The trend toward quality management, more than anything else, changed this perspective. W. E. Deming, the international quality expert, emphasized that good employees who are always improving are the key to successful quality management and a company's ultimate survival. More than half of Deming's 14 points for quality improvement relate to employees. His point is that if a company is to attain its goals for quality improvement and customer service, its employees must be involved and committed. However, to get employees "with the program," the company must regard them and manage them as a valuable resource. Moreover, the company must have a commitment to its employees.

Another thing that has changed the way companies regard employees and work is the shift in the U.S. economy toward the service sector and away from manufacturing. Since services tend to be more people-intensive than capital-intensive, human resources are becoming a more important competitive factor for service companies. Advances in information technologies have also changed the working environment, especially in service companies. Because they rely heavily on information technology and communication, services need employees who are technically skilled and can communicate effectively with customers. They also need flexible employees who can apply these skills to a variety of tasks and who are continuously trained to keep up with rapid advances in information technology.

Increasing technological advances in equipment and machinery have also resulted in manufacturing work that is more technically sophisticated. Employees are required to be better educated, have greater skill levels, and have greater technical expertise, and are expected to take on greater responsibility. This work environment is a result of changing technologies and international market conditions, global competition that emphasizes diverse products, and an emphasis on product and service quality.

In this chapter we first discuss employees' role in achieving a company's goals for quality. Next we provide a perspective on how work has developed and changed in the United States and then look at some of the current trends in human resources. We will also discuss some of the traditional aspects of work and job design.

Most successful quality-oriented firms today recognize the importance of their employees when developing a competitive strategy. Quality management is an integral part of most companies' strategic design, and the role of employees is an important aspect of quality management. To change management's traditional control-oriented relationship with employees to one of cooperation, mutual trust, teamwork, and goal orientation necessary in a quality-focused company generally requires a long-term commitment as a key part of a company's strategic plan.

In the traditional management–employee relationship, employees are given precise directions to achieve narrowly defined individual objectives. They are rewarded with merit pay based on individual performance in competition with their coworkers. Often individual excellence is rewarded while other employees look on in envy. In a successful quality management program, employees are given broad latitude in their jobs, they are encouraged to improvise, and they have the power to use their own initiative to correct and prevent problems. Strategic goals are for quality and customer service instead of maximizing profit or minimizing cost, and rewards are based on group achievement. Instead of limited training for specific, narrowly defined jobs, employees are trained in a broad range of skills so they know more about the entire productive process, making them flexible in where they can work.

To manage human resources from this perspective, a company must focus on employees as a key, even central, component in their strategic design. All of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award winners have a pervasive human resource focus. Sears's "employee-customer-profit chain" model for long-term company success has "employees" as the model's driving force. Federal Express's strategic philosophy, "People, Service, Profit," starts with people, reflecting its belief that its employees are its most important resource.

Companies that successfully integrate this kind of "employees first" philosophy into their strategic design share several common characteristics. Employee training and education are recognized as necessary long-term investments. Strategic planning for product and technological innovation is tied to the development of employees' skills, not only to help in the product development process but also to carry out innovations as they come to fruition. Motorola provides employees with 160 hours of training annually to keep up with technological changes and to learn how to understand and compete in newly emerging global markets.

Another characteristic of companies with a strategic design that focuses on quality is that employees have the power to make decisions that will improve quality and customer service. At AT&T employees can stop a production line if they detect a quality problem, and an employee at Ritz-Carlton can spend several thousand dollars to satisfy a guest, on his or her own initiative.

To make sure their strategic design for human resources is working, companies regularly monitor employee satisfaction using surveys and make changes when problems are identified. All Baldrige Quality Award-winning companies conduct annual employee surveys, to assess employee satisfaction and make improvements.

A safe, healthy working environment is a basic necessity to keep employees satisfied. Successful companies provide special services like recreational activities, day care, flexible work hours, cultural events, picnics, and fitness centers. Notice that these are services that treat employees like customers, an acknowledgment that there is a direct and powerful link between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction.

Strategic goals for quality and customer satisfaction require teamwork and group participation. Quality-oriented companies want all employees to be team members to identify and solve quality-related problems. Team members and individuals are encouraged to make suggestions to improve processes. The motivation for employee suggestions is viewed as that of a concerned family member, not as a complainant or as "sticking one's nose in."

It is important that employees understand what the strategic goals of the company are and that they feel like they can participate in achieving these goals. Employees need to believe they make a difference, to be committed to goals and have pride in their work. Employee commitment and participation in the strategic plan can be enhanced if employees are involved in the planning process, especially at the local level. As the strategic plan passes down through the organization to the employee level, employees can participate in the development of local plans to achieve overall corporate goals.

The principles of scientific management developed by F. W. Taylor in the 1880s and 1890s dominated operations management during the first part of the twentieth century. Taylor's approach was to break jobs down into their most elemental activities and to simplify job designs so that only limited skills were required to learn a job, thus minimizing the time required for learning. This approach divided the jobs requiring less skill from the work required to set up machinery and maintain it, which required greater skill. In Taylor's system, a job is the set of all the tasks performed by a worker, tasks are individual activities consisting of elements, which encompass several job motions, or basic physical movements.

Scientific management involves breaking down jobs into elemental activities and simplifying job design.

• Jobs: comprise a set of tasks, elements, and job motions (basic physical movements).

Scientific management broke down a job into its simplest elements and motions, eliminated unnecessary motions, and then divided the tasks among several workers so that each would require only minimal skill. This system enabled companies to hire large numbers of cheap, unskilled laborers, who were basically interchangeable and easily replaced. If a worker was fired or quit, another could easily be placed on the job with virtually no training expense. In this system, the timing of job elements (by stopwatch) enabled management to develop standard times for producing one unit of output. Workers were paid according to their total output in a piece-rate system. A worker was paid "extra" wages according to the amount he or she exceeded the "standard" daily output. Such a wage system is based on the premise that the single motivating factor for a worker to increase output is monetary reward.

• Tasks: individual, defined job activities that consist of one or more elements.

Traditionally, time has been a measure of job efficiency.

In a piece-rate wage system, pay is based on output.

F. W. Taylor's work was not immediately accepted or implemented. This system required high volumes of output to make the large number of workers needed for the expanded number of jobs cost effective. The principles of scientific management and mass production were brought together by Henry Ford and the assembly-line production of automobiles.

Between 1908 and 1929, Ford Motor Company created and maintained a mass market for the Model-T automobile, more than 15 million of which were eventually produced. During this period, Ford expanded production output by combining standardized parts and product design, continuous-flow production, and Taylor's scientific management. These elements were encompassed in the assembly-line production process.

The adoption of scientific management at Ford was the catalyst for its subsequent widespread acceptance.

On an assembly line, workers no longer moved from place to place to perform tasks, as they had in the factory/shop. Instead they remained at a single workplace, and the work was conveyed to them along the assembly line. Technology had advanced from the general-purpose machinery available at the turn of the century, which required the abilities of a skilled machinist, to highly specialized, semiautomatic machine tools, which required less skill to feed parts into or perform repetitive tasks. Fifteen thousand of these machines were installed at Ford's Highland Park plant. The pace of work was established mechanically by the line and not by the worker or management. The jobs along the line were broken down into highly repetitive, simple tasks.

Assembly-line production meshed with the principles of scientific management.

The assembly line at Ford was enormously successful. The amount of labor time required to assemble a Model-T chassis was reduced from more than 12 hours in 1908 to a little less than 3 hours by 1913. By 1914 the average time for some tasks was as low as 11/2 minutes. The basic assembly-line structure and many job designs that existed in 1914 remained virtually unchanged for the next 50 years.

Scientific management had obvious advantages. It resulted in increased output and lower labor costs. Workers could easily be replaced and trained at low cost, taking advantage of a large pool of cheap unskilled labor shifting from farms to industry. Because of low-cost mass production, the U.S. standard of living was increased enormously and became the envy of the rest of the world. It also allowed unskilled, uneducated workers to gain employment based almost solely on their willingness to work hard physically at jobs that were mentally undemanding.

Advantages of task specialization include high output, low costs, and minimal training.

Scientific management also proved to have serious disadvantages. Workers frequently became bored and dissatisfied with the numbing repetition of simple job tasks that required little thought, ingenuity, or responsibility. The skill level required in repetitive, specialized tasks is so low that workers do not have the opportunity to prove their worth or abilities for advancement. Repetitive tasks requiring the same monotonous physical motions can result in unnatural physical and mental fatigue.

Disadvantages of task specialization include boredom, lack of motivation, and physical and mental fatigue.

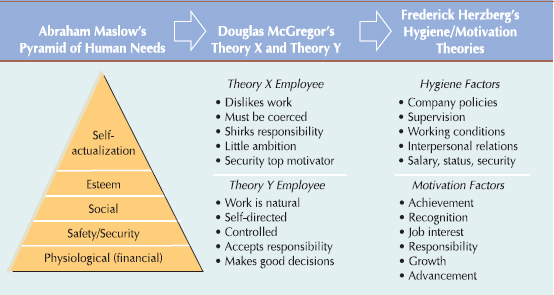

Modern psychologists and behaviorists in the 1950s and 1960s eschewed the principles of scientific management, and they developed theories (as summarized in Table 8.1), that proposed that in order to get employees to work productively and efficiently they must be motivated. Motivation is a willingness by an employee to work hard to achieve the company's goals because that effort satisfies some employees' need or objective. Thus, employee motivation is a key factor in achieving company goals such as product quality and creating a quality workplace. However, different things motivate employees. Obviously, financial compensation is a major motivating factor, but it is not the only one and may not be the most important. Other factors that motivate employees include self-actualization (such as integrity, responsibility, and naturalness), achievement and accomplishment, recognition, relationships with coworkers and supervisors, the type and degree of work supervision, job interest, trust and responsibility, and the opportunity for growth and advancement.

• Motivation: a willingness to work hard because that effort satisfies an employee need.

In general, job performance is a function of motivation combined with ability. Ability depends on education, experience, and training, and its improvement can follow a slow but clearly defined process. On the other hand, motivation can be improved more quickly, but there is no clear-cut process for motivating people. However, certain basic elements in job design and management have been shown to improve motivation, including

positive reinforcement and feedback

effective organization and discipline

fair treatment of people

satisfaction of employee needs

setting of work-related goals

design of jobs to fit the employee

work responsibility

empowerment

restructuring of jobs when necessary

rewards based on company as well as individual performance

achievement of company goals

During the last two decades of the twentieth century the competitive advantage gained by many Japanese companies in international markets, and especially in the automobile industry, caused U.S. firms to reevaluate their management practices vis-à-vis those of the Japanese. Human resources management is one area where there was a striking difference between Japanese and U.S. approaches and results. For example, in the 1980s one Japanese automobile company was able to assemble a car with half the blue-collar labor of a comparable U.S. auto company—about 14 hours in Japan, compared with 25 hours in the United States. Japan had not adopted the traditional Western approaches to work. Instead Japanese work allowed for more individual worker responsibility and less supervision, group work and interaction, higher worker skill levels, and training across a variety of tasks and jobs. There was initially a tendency among Americans to think that these characteristics were unique to the Japanese culture. However, the successes of U.S. companies such as Ford and Motorola in implementing quality-management programs as well as successful Japanese companies operating in the United States, such as Nissan and Honda, showed that cultural factors were less important than management practices. As a result certain contemporary trends in human resource management became the norm for successful companies in the United States and abroad.

Japanese successes are due less to cultural factors than to management practices.

In companies with a commitment to quality, job training is extensive and varied. Expectations for performance and advancement from both the employee and management tend to be high. Typically, numerous courses are available for training in different jobs and functions. Job training is considered part of a structured career-development system that includes cross training and job rotation. This system of training and job rotation enhances the flexibility of the production process we mentioned earlier. It creates talent reserves that can be used as the need arises when products or processes change or the workforce is reduced.

Training is a major feature of all companies with quality management programs. Two of W. E. Deming's 14 points refer to employee education and training. Most large companies have extensive training staffs with state-of-the-art facilities. Federal Express has a television network that broadcasts more than 2000 different training course titles to employees. Many UPS employees are part-time college students, but each receives more training than most skilled factory workers in the United States.

Two of Deming's 14 points refer to employee education and training.

In cross training an employee learns more than one job in the company. Cross training has a number of attractive features that make it beneficial to the company and the employee. For the company it provides a safety measure with more job coverage in the event of employee resignations and absenteeism, and sudden increases in a particular job activity. Employees are given more knowledge and variety so that they won't get as easily bored, they will find more value in what they do, and their interest level in the company will increase. Because of their increased knowledge, they will have the opportunity to move to other jobs within the company without leaving. Employees will respect each other because they will be more familiar with each other's jobs. However, cross training requires a significant investment in time and money, so the company should be committed to its implementation and sure of the benefits it hopes to realize from cross training.

• Cross training: an employee learns more than one job.

Job rotation is not exactly the same as cross training. Cross training gives an employee the ability to move between jobs if needed. Job rotation requires cross training, but it also includes the horizontal movement between two or more jobs according to a plan or schedule. This not only creates a flexible employee, but it also reduces boredom and increases employee interest.

• Job rotation: the horizontal movement between two or more jobs according to a plan.

The objective of job enrichment is to create more opportunities for individual achievement and recognition by adding variety, responsibility, and accountability to the job. This can also lead to greater worker autonomy, increased task identity, and greater direct contact with other workers. Frederick Herzberg (Table 8.1) developed the following set of principles for job enrichment:

• Vertical job enlargement: allows employees control their work.

• Horizontal job enlargement: an employee is assigned complete unit of work with defined start and end.

Allow employees control over their own work and some of the supervisory responsibilities for the job, while retaining accountability, also called vertical job enlargement.

Assign each worker a complete unit of work that includes all the tasks necessary to complete a process or product with clearly defined start and end points so that the employee feels a sense of closure and achievement. This is also called horizontal job enlargement.

Make periodic reports available to workers instead of just supervisors.

Introduce new and more difficult tasks into the job.

Encourage development of expertise by assigning individuals to specialized tasks.

Empowerment is giving employees responsibility and authority to make decisions. For quality management programs to work, it is generally conceded that employees must be empowered so that they are willing to innovate and act on their own in an atmosphere of trust and respect. Five of W. E. Deming's 14 points for quality improvement (see page 61) relate to employee empowerment. Empowerment requires employee education and training, and participation in goal setting. The advantages of empowerment include more attention to product quality and the ability to fix quality problems quickly, increased respect and trust among employees, lower absenteeism and higher productivity, more satisfying work, less conflict with management, and fewer middle managers. However, empowerment can also have some negative aspects. Employees may abuse the power given to them; empowerment may provide too much responsibility for some employees; it may create conflicts with middle management; it will require additional training for employees and managers which can be costly; group work, which often is an integral part of empowerment, can be time-consuming and some employees may not make good decisions.

• Empowerment: giving employees authority to make decisions.

A Motorola sales representative is empowered to replace a customer's defective product up to six years after its purchase. GM plant employees can call in suppliers to help them solve problems. Federal Express employees are empowered to do whatever it takes to ensure 100% customer satisfaction. The authority of employees to halt an entire production operation or line on their own initiative if they discover a quality problem is well documented at companies like AT&T.

Empowerment and employee involvement are often realized through work groups or teams. Quality circles, discussed in Chapter 2 ("Quality Management"), in which a group of 8 to 10 employees plus their supervisor work on problems in their immediate work area, is a well-known example of a team approach. Teams can differ according to their purpose, level of responsibility, and longevity. Some teams are established to work on a specific problem and then disband; others are more long-term, formed to monitor a work area or process for continual improvement. Most teams are not totally democratic and have some supervisory oversight, although some have more authority than others. Quality circles typically have a supervisor in charge. In general, for teams to be effective, they must know what their purpose and roles are relative to the company's goal's, as well as the extent of their empowerment, have the skills and training necessary to achieve their goals, and possess the ability to work together as a team.

Self-directed teams, though not totally independent, are usually empowered to make decisions and changes relative to the processes in their own work area. This degree of responsibility is based on trust and management's belief that the people who are closest to a work process know how to make it work best. Team members tend to feel more responsibility to make their solutions work, and companies typically reward teams for performance improvement.

Self-directed teams generally require more training to work together as a team; however, benefits include less managerial control (and fewer managers), quicker identification and solution of problems, more job satisfaction, positive peer pressure, and a feeling of "not wanting to let the team down," common to sports teams and military groups. Alternatively, such teams can have some negative aspects. Supervisors and managers may have difficulty adjusting to their changed role in which they monitor and oversee rather than direct work. Also, conflict between team members can hinder a team's effectiveness.

Flexible work schedules or flextime is becoming an increasingly important workplace format. It refers to a variety of arrangements in which fixed times of arrival and departure are replaced by a combination of "core" or fixed time and flexible time. Core time is the designated period during which all employees are present, say 9:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Flexible time is part of the daily work schedule where employees can choose their time of arrival and departure. In some cases, an employee may bank or credit hours—that is, work more hours one day and bank those hours in order to take a shorter work day in the future. In other cases, an employee may vary work days during the week, for example, work four 10-hour days followed by a three-day weekend. While flextime helps the company attract and retain employees and promotes job satisfaction, it can make it difficult to compensate for sudden changes in the workload or problems that can arise that require quick reactions.

• Flextime: part of a daily work schedule in which employees can choose time of arrival and departure.

An alternative workplace is a combination of nontraditional work locations, settings, and practices that supplements or replaces the traditional office. An alternative workplace can be a home office, a satellite office, a shared office, a shared desk or an open workspace where many employees work side-by-side. Another form of alternative workplace is telecommuting, performing work electronically wherever the worker chooses.

• Alternative workplace: a nontraditional work location.

The motivation for companies to create alternative workplaces is primarily financial. Eliminating physical office space—that is, real estate—and reducing related overhead costs can result in significant cost reductions. In one five-year period, IBM realized $1 billion in real estate savings alone by equipping and training 17% of its worldwide workforce to work in alternative workplaces. Alternative workplaces can increase productivity by relieving employees of typical time-consuming office routines, allowing them more time to devote to customers. They can also help companies recruit and retain talented, motivated employees who find the flexibility of telecommuting or a home office very attractive. Eliminating commuting time to a remote office can save employees substantial work time. Customer satisfaction can also increase as customers find it easier to contact employees and receive more personalized attention.

In general, companies that use alternative workplaces employ a mix of different formats and tailor the workplace to fit specific company needs. There are also costs associated with establishing alternative workplace formats, including training, hardware and software, networks, phone charges, technical support, and equipment, although these costs are usually less than real estate costs, which are ever-increasing. Of course, alternative workplaces are not feasible for some companies, such as manufacturing companies, which require employees to be located at specific workstations, facilities, or stationary equipment or which require direct management supervision. Employees who work on an assembly line or in a hotel are not candidates for an alternative workplace. Alternative workplaces are more appropriate for companies that are informational—that is, they operate through voice and data communication between their employees and their customers.

Telecommuting, where employees work from home or some other alternative location is becoming increasingly popular. It has been shown to increase productivity and job satisfaction and reduce facility costs.

One of the more increasingly common new alternative workplace formats is telecommuting, also referred to as "telework," in which employees work electronically from whatever location they choose, either exclusively or some of the time. It is estimated that about 40% of U.S. companies offer some form of telecommuting to employees. Companies that use telecommuting sites experience such benefits as lower real estate costs, reduced turnover, decreased absenteeism and leave usage, increased productivity, and increased ability to comply with federal workplace laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act. At PeopleSoft, telecommuting is the predominant form of work for the whole company. At IBM 25% of their 320,000 employees telecommute, which results in an estimated annual savings of $700 million in real estate costs alone. AT&T estimates it saves $550 million annually as a results of telecommunity.

• Telecommuting: employees work electronically from a location they choose.

It has been estimated that through telecommuting absenteeism can be reduced by as much as 25%. For employees, telecommuting eliminates commuting time and travel costs, allows for a more flexible work schedule, and allows them to blend work with family and personal responsibilities. Companies that offer telecommuting indicate productivity increases 10 to 20 percent and job satisfaction also increases.

Telecommuting also has negative aspects. It may negatively affect the relationship between employees and their immediate supervisors. Supervisors and middle managers may feel uncomfortable not having employees under direct visual surveillance. Furthermore, they may feel that they do not have control and authority over their employees if they are not physically present. In fact, some employees may not be well suited for telecommuting; they may not be self-motivated and may require more direct supervision and external motivation. The technology that allows employees to work anywhere, anytime, can also lead to employees who cannot "disconnect" from their jobs.

A trend among service companies in particular is the use of temporary, or contingent, employees. Part-time employees accounted for over 40% of job growth in the retail industry during the 1990s. Fast-food and restaurant chains, retail companies, package delivery services, and financial firms tend to use a large number of temporary employees. Companies that have seasonal demand make extensive use of temporary employees. L.L. Bean needs a lot more telephone service operators, and UPS needs many more package sorters in the weeks before Christmas. Sometimes a company will undertake a project requiring technical expertise its permanent employees do not have. Instead of reassigning or retraining its employees, the company will bring in temporary employees having the necessary expertise. Some firms lease people for jobs, especially for computer services. As companies downsize to cut costs, they turn to temporary employees to fill temporary needs without adding to their long-term cost base. People with computer skills able to work from home have also increased the pool of available temporary workers.

Unfortunately, temporary employees do not always have the commitment to goals for quality and service that a company might want. Companies dependent on temporary employees may suffer not only the inconsistent levels of their work ethic and skills, they may also sacrifice productivity for lower costs. To offset this possible inconsistency and to protect product and service quality, firms sometimes try to hire temporary employees only into isolated work areas away from their core businesses that most directly affect quality.

Part-time employment is a key aspect at some companies like UPS (see the "Along the Supply Chain" box on the next page); however part-time employment does not always have positive results. As part of a retooling plan at Home Depot, an attempt was made to change the sales floor staff mix from 30% part-time to 50% in order to cut costs and gain flexibility to cover busy times of the day. The plan was abandoned after customers complained about bad service and full-time employees complained about the part-timers' lack of commitment. It also violated the perception among employees that Home Depot was a place where someone could build a career.

Good human resource management practices or motivation factors cannot compensate for insufficient monetary rewards. If the reward is perceived as good, other things will motivate employees to give their best performance. Self-motivation can go only so far—it must be reinforced by financial rewards. Merit must be measured and rewarded regularly; otherwise performance levels will not be sustained.

The two traditional forms of employee payment are the hourly wage and the individual incentive, or piece-rate, wage, both of which are tied to time. The hourly wage is self-explanatory; the longer someone works, the more he or she is paid. In a piece-rate system, employees are paid for the number of units they produce during the workday. The faster the employee performs, the more output generated and the greater the pay. These two forms of payment are also frequently combined with a guaranteed base hourly wage and additional incentive piece-rate payments based on the number of units produced above a standard hourly rate of output. Other basic forms of compensation include straight salary, the most common form of payment for management, and commissions, a payment system usually applied to sales and salespeople.

An individual piece-rate system provides incentive to increase output, but it does not ensure high quality. It can do just the opposite! In an effort to produce as much as possible, the worker will become sloppy, take shortcuts, and pay less attention to detail. As a result, some quality-focused companies have tried to move away from individual wage incentive systems based on output and time. There has been a trend toward other measures of performance, such as quality, productivity, cost reduction, and the achievement of organizational goals. These systems usually combine an hourly base payment or even a salary with some form of incentive payment. However, incentives are not always individual but are tied to group, team, or company performance.

Gainsharing is an incentive plan that includes employees in a common effort to achieve a company's objectives in which they share in the gains. Although gainsharing systems vary broadly, they all generally include some type of financial measurement and frequent feedback system to monitor company performance and distribute gains periodically in the form of bonuses. Profit sharing sets aside some portion of company profits and distributes it among employees usually at the end of the fiscal year. The objective behind both incentive programs is to create a sense among employees that it is in their self-interest for the company to do well: the company wants employees to buy into the company's financial goals.

• Gainsharing: an incentive plan joins employees in a common effort to achieve company goals, who share in gain.

• Profit sharing: sets aside a portion of profits for employees at year's end.

Both programs have been shown to result in an increase in employee productivity; however, gainsharing is different from profit sharing in several ways. Gainsharing programs provide frequent payouts or bonuses, sometimes weekly or monthly, while profit-sharing bonuses are awarded once a year. Thus, gainsharing provides a more frequent reinforcement of good performance for the average employee. It is also generally easier for average employees to see results of gainsharing than profit sharing. Gainsharing focuses more on performance measures that are directly linked to the performance of employees or groups of employees than does profit sharing. Gainsharing spells out clearly what employees need to do to achieve a short-term goal and what will happen when they do achieve it. Profit sharing does not have the same emphasis on specifi cally what needs to happen to achieve short-term (weekly or monthly) goals. For these reasons, profit sharing is typically an incentive program that is more applicable to higher level employees and executives.

Diversity in U.S. companies has been a critical management issue for several decades. However, as more and more companies move into the global marketplace, diversity has become an even more pervasive factor in human resource management around the world. The spread of global business combined with the geographic mobility of employees has resulted in companies with a more diverse workforce than ever before. U.S. companies outsource business activities and operate facilities and businesses overseas with a mix of foreign and U.S. management teams and employees, and foreign companies operate plants and businesses in the United States with similar mixes. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 4 out of every 10 people entering the workforce during the decade from 1998 to 2008 were members of minority groups. In 2005 14% of the working age population was Hispanic and by 2050 it is projected to be 31%.

In order to be successful with a diverse workforce, companies must provide a climate in which all employees feel comfortable, can do their job, feel like they are valued by the organization, and perceive that they are treated fairly. However, inequalities too often exist for employees because of race, gender, religion, cultural origin, age, and physical or mental limitations. The elimination of racism, sexism, cultural indifference, and religious intolerance cannot be mandated by higher management or managed by financial incentives. Companies as a whole, starting with top management, must develop a strategic approach to managing diversity in order to meet the challenges posed by a diverse workforce.

In the United States affirmative action and equal opportunity are sometimes confused with managing diversity, but they are not the same thing. Affirmative action is an outgrowth of laws and regulations and is government initiated and mandated. It contains goals and timetables designed to increase the level of participation by women and minorities to attain parity levels in a company's workforce. Affirmative action is not directly concerned with increasing company success or increasing profits. Alternatively, managing diversity is the process of creating a work environment in which all employees can contribute to their full potential in order to achieve a company's goals. It is voluntary in nature, not mandated. It seeks to improve internal communications and interpersonal relationships, resolve conflict, and in doing so increase product quality, productivity, and efficiency. Managing diversity is creating an environment where everyone works in concert to do the best job possible. Whereas affirmative action has a short-term result, managing diversity is a long-term process. The objective of managing diversity is to find a way to let everyone do their best so that the company can gain a competitive edge.

Although affirmative action and diversity management are not the same thing, they are not independent of each other. A company that successfully manages diversity and implements successful programs that eliminate diversity issues and discrimination will also eliminate costly affirmative action liability and government mandates.

Although there is no magic formula for successfully managing diversity, education, awareness, communication, fairness, and commitment are critical elements in the process. We have explained on several occasions that employee training is an essential element in achieving product quality; the same holds true for creating a quality work environment for a diverse workforce. Prejudice feeds on ignorance. Employees must be educated about racial, gender, religious, and ethnic differences; they must be made aware of what it is like to be someone who is different from themselves. This also requires that lines of communication be open between different groups, and between employees and management. Most importantly, successful diversity management requires a commitment from top management. Although top management cannot mandate that the workplace be diversity friendly, strong leadership can successfully influence it.

• Managing diversity: includes education, awareness, communication, fairness, and commitment.

A survey of Fortune 1000 companies conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management and Fortune magazine showed that diversity initiatives and programs can have a beneficial effect on company profits and success. Nearly all of the survey respondents (91%) indicated that their company's diversity initiatives helped them to maintain a competitive advantage by improving corporate culture (83%), improving employee morale (79%), decreasing interpersonal conflict among employees (58%), and increasing creativity (59%), and productivity (52%). Seventy-seven percent of the respondents indicated that their diversity initiatives improved employee recruitment, and 52% claimed they improved customer relations.

Many companies have discovered that a diverse workforce is no longer just a legally or culturally mandated requirement, but a beneficial aspect of their corporate culture that can have a bottom-line impact. At Frito-Lay, the snack food division of PepsiCo, the Latino Employee Network (called Adelante) played a major role in the development of Doritos Guacamole Flavored Tortilla Chips. Members of the network provided feedback on taste and packaging that ensured that the new product would be regarded as authentic. This helped make the new Doritos one of the most successful product launches in the company's history, with more than $100 million in sales in its first year. Aetna has discovered that it is critical for their employees to literally speak the language of their customers, making multilingual employees invaluable. Aetna often targets their recruiting efforts to identify individuals who can speak more than one language for specific functional segments in the company. Aetna, like many companies, has also found that diversity can impact community involvement and thus, their marketplace. By supporting diversity-related community programs, Aetna enhances its presence and brand reputation in key markets, resulting in more business opportunities.

The most common diversity initiatives and programs are recruiting efforts designed to increase diversity; diversity training; education and awareness programs; and community out-reach. However, these initiatives can be time consuming, costly, and sometimes generate false hopes.

One approach being used by a number of companies is to create groups or networks that enable employees with diverse backgrounds to interact with each other. Kodak has a number of diversity groups, including a Women's Forum and a gay-employees network, which collaborate on different workplace issues. Many employees belong to multiple groups and learn about each others' issues and concerns, which helps develop sensitivity and mutual respect. Unisys and AT&T have resource groups for disabled employees which allow them to provide suggestions for designing products to make them more accessible to people with disabilities. Other diversity initiatives that have shown success within companies include internships, mentoring programs, career management programs, and skill enhancement programs.

Trends toward the globalization of companies, the use of global teams within and across companies, and global outsourcing have resulted in unique diversity issues. Cultural and language differences and geography are significant barriers to managing a globally diverse workforce. E-mails, faxes, the Internet, phones, and air travel make managing a global workforce possible but not necessarily effective.

In the case of culturally diverse groups, differences may be more subtle, and defined diversity programs may be less effective in dealing with them. Some nationalities and cultures have a more relaxed view of time than, say, Americans or Europeans; deadlines are less important. In some cultures, religious and national holidays have more significance than in others. Americans will frequently work at home in the evening, stay late at work, or work over the weekend or on vacations, and on the average take less vacation time than employees in most European countries; in many foreign countries such behavior is unheard of. Some cultures seem to have their own rules of communication. An employee in a foreign country, for example, may politely nod yes in response to a question from a U.S. manager as a polite face-saving gesture, when in fact it's not an indication of agreement at all.

Such cultural differences require unique forms of diversity management. Managers cannot interpret their employees' behavior through their own cultural background. It is important to identify critical cultural elements such as important holidays and a culturally acceptable work schedule, and to learn the informal rules of communication that may exist in a foreign culture among a diverse group of employees. It is often helpful to use a third party who is better able to bridge the cultural gap as a go-between. A manager who is culturally aware, and most importantly, speaks the language, is less likely to incorrectly interpret the behavior of diverse employees. Similarly, it is beneficial to teach employees the cultural norm for the organization so that they understand all the rules.

These Chinese workers are sewing jeans in a garment factory in Shenzhen, one of mainland China's "Special Economic Zones," which provide more .exible government economic policies including tax incentives for foreign investments, emphasis on joint sino-foreign ventures, greater independence for international trade activities, and export-oriented products.

In the preceding sections we have discussed how to motivate employees to perform well in their jobs. A key element in employee motivation and job performance is to make sure the employee is well suited for a job and vice versa. If a job is not designed properly and it is not a good fit for the employee, then it will not be performed well. Frederick Herzberg identified several attributes of good job design, as follows:

An appropriate degree of repetitiveness

An appropriate degree of attention and mental absorption

Some employee responsibility for decisions and discretion

Employee control over their own job

Goals and achievement feedback

A perceived contribution to a useful product or service

Opportunities for personal relationships and friendships

Some influence over the way work is carried out in groups

Use of skills

In this section we will focus on the factors that must be considered in job design—the things that must be considered to create jobs with the attributes listed above.

Table 8.2. Elements of Job Design

Worker Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

• Description of tasks to be performed | • Capability requirements | • Workplace location |

• Task sequence | • Performance requirements | • Process location |

• Function of tasks | • Evaluation | • Temperature and humidity |

• Frequency of tasks | • Skill level | • Lighting |

• Criticality of tasks | • Job training | • Ventilation |

• Relationship with other jobs/tasks | • Physical requirements | • Safety |

• Performance requirements | • Mental stress | • Logistics |

• Information requirements | • Boredom | • Space requirements |

• Control requirements | • Motivation | • Noise |

• Error possibilities | • Number of workers | • Vibration |

• Task duration(s) | • Level of responsibility | |

• Equipment requirements | • Monitoring level | |

• Quality responsibility | ||

• Empowerment level |

The elements of job design fall into three categories: an analysis of the tasks included in the job, employee requirements, and the environment in which the job takes place. These categories address the questions of how the job is performed, who does it, and where it is done. Table 8.2 summarizes a selection of individual elements that would generally be considered in the job design process.

Task analysis determines how to do each task and how all the tasks fit together to form a job. It includes defining the individual tasks and determining their most efficient sequence, their duration, their relationship with other tasks, and their frequency. Task analysis should be sufficiently detailed so that it results in a step-by-step procedure for the job. The sequence of tasks in some jobs is a logical ordering; for example, the wedges of material used in making a baseball cap must be cut before they can be sewn together, and they must all be sewn together before the cap bill can be attached. The performance requirements of a task can be the time required to complete the task, the accuracy in performing the task to specifications, the output level or productivity yield, or quality performance. The performance of some tasks requires information such as a measurement (cutting furniture pieces), temperature (food processing), weight (filling bags of fertilizer), or a litmus test (for a chemical process).

Task analysis: how tasks fit together to form a job.

Performance requirements of a task: time, accuracy, productivity, quality.

Worker analysis determines the characteristics the worker must possess to meet the job requirements, the responsibilities the worker will have in the job, and how the worker will be rewarded. Some jobs require manual labor and physical strength, whereas others require none. Physical requirements are assessed not only to make sure the right worker is placed in a job but also to determine if the physical requirements are excessive, necessitating redesign. The same type of design questions must be addressed for mental stress.

Determining worker capabilities and responsibilities for a job.

Environmental analysis refers to the physical location of the job in the production or service facility and the environmental conditions that must exist. These conditions include things such as proper temperature, lighting, ventilation, and noise. The production of microchips requires an extremely clean, climatically controlled, enclosed environment. Detail work, such as engraving or sewing, requires proper lighting; some jobs that create dust levels, such as lint in textile operations, require proper ventilation. Some jobs require a large amount of space around the immediate job area.

Job environment: the physical characteristics and location of a job.

Put simply, ergonomics as it is applied to work is fitting the task to the person. It deals with the interaction of work, technology, and humans. Ergonomics applies human sciences like anatomy, physiology, and psychology to the design of the work environment and jobs, and objects and equipment used in work. The objective of ergonomics is to make the best use of employees' capabilities while maintaining the employees' health and well-being. The job should never limit the employee or compromise an employee's capabilities or physical and mental health because of poor job design. Good ergonomics shortens learning times; makes the job easier with less fatigue; improves equipment maintenance; reduces absenteeism, labor turnover, and job stress and injury; and meets legislative requirements for health and safety. In order to achieve these objectives, the job activity must be carefully analyzed, and the demands placed on the employee must be understood.

• Ergonomics: fitting the task to the person in a work environment.

Technology has broadened the scope of job design in the United States and overseas.

The contribution of anatomy in ergonomics is the improvement of the physical aspect of the job: achieving a good physical fit between the employee and the things the employee uses on the job whether it's a hand tool, a computer, a video camera, a forklift, or a lathe. Physiology is concerned with how the body functions. It addresses the energy required from the employee to do the job as well as the acceptable workload and work rate, and the physical working conditions—heat, cold, light, noise, vibration, and space. Psychology is concerned with the human mind. Its objective is to create a good psychological fit between the employee and the job.

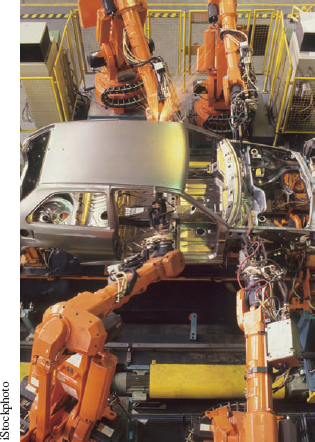

Robots do not necessarily perform a job faster than humans, but they can tolerate hostile environments, work longer hours, and do a job more consistently. Robots are used for a wide range of manufacturing jobs, including material handling, machining, assembly, and inspection.

The worker-machine interface is possibly the most crucial aspect of job design, both in manufacturing industries and in service companies where workers interface with computers. New technologies have increased the educational requirements and need for employee training. The development of computer technology and systems has heightened the need for workers with better skills and more job training.

During the 1990s, there was a substantial investment in new plants and equipment in the United States to compete globally. Companies developed and installed a new generation of automated equipment and robotics that enhanced their abilities to achieve higher output and lower costs. This new equipment also reduced the manual labor necessary to perform jobs and improve safety. Computer systems provided workers with an expanded array of information that increased their ability to identify and locate problems in the production process and monitor product quality. New job designs and redesigns of existing jobs were required that reflected these new technologies.

Part of job design is to study the methods used in the work included in the job to see how it should be done. This has traditionally been referred to as methods analysis, or simply work methods.

Work methods: studying how a job is done

Methods analysis is used to redesign or improve existing jobs. An analyst will study an existing job to determine if the work is being done in the most efficient manner possible; if all the present tasks are necessary; or if new tasks should be added. The analyst might also want to see how the job fits in with other jobs—that is, how well a job is integrated into the overall production process or a sequence of jobs. The development and installation of new machinery or equipment, new products or product changes, and changes in quality standards can all require that a job be analyzed for redesign.

Methods analysis is also used to develop new jobs. In this case, the analyst must work with a description or outline of a proposed job and attempt to develop a mental picture of how the job will be performed.

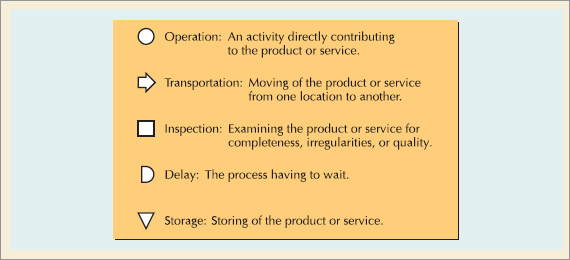

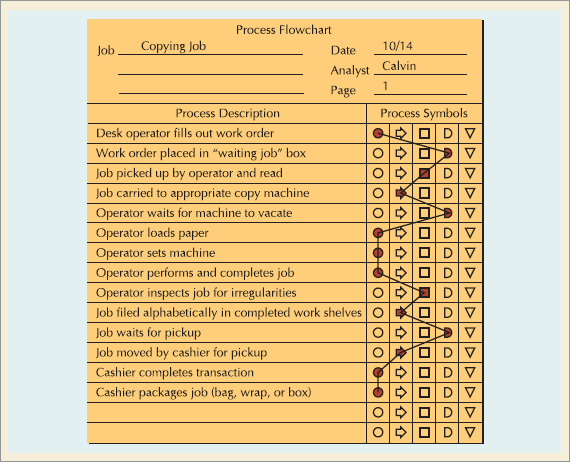

The primary tools of methods analysis are a variety of charts that illustrate in different ways how a job or a work process is done. These charts allow supervisors, managers, and workers to see how a job is accomplished and to get their input and feedback on the design or redesign process. Two of the more popular charts are the process flowchart and the worker–machine chart.

A process flowchart is used to analyze how the steps of a job or how a set of jobs fit together into the overall flow of the production process. Examples might include the flow of a product through a manufacturing assembly process, the making of a pizza, the activities of a surgical team in an operating room, or the processing of a catalogue mail or telephone order.

• Process flowchart: a graph of the steps of a job.

A process flowchart uses some basic symbols shown in Figure 8.1 to describe the tasks or steps in a job or a series of jobs. The symbols are connected by lines on the chart to show the flow of the process.

Often a process flowchart is used in combination with other types of methods analysis charts and a written job description to form a comprehensive and detailed picture of a job. Essentially, the methods analyst is a "job detective," who wants to get as much evidence as possible about a job from as many perspectives as possible in order to improve the job.

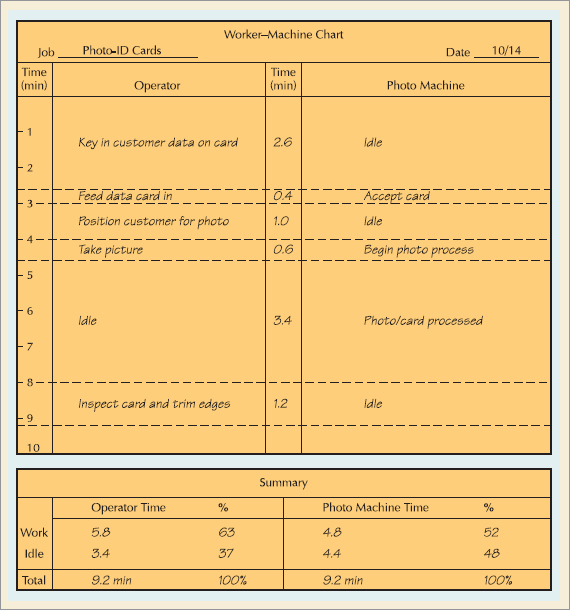

A worker-machine chart illustrates the amount of time a worker and a machine are working or idle in a job. This type of chart is occasionally used in conjunction with a process flowchart when the job process includes equipment or machinery. The worker-machine chart shows if the worker's time and the machine time are being used efficiently—that is, if the worker or machine is idle an excessive amount of time.

• Worker-machine chart: determines if worker and machine time are used efficiently.

Another type of worker-machine chart is the gang process chart, which illustrates a job in which a team of workers are interacting with a piece of equipment or a machine. Examples include workers at a coal furnace in a steel mill or a military gunnery team on a battleship. A gang chart is constructed the same way as the chart in Figure 8.3, except there are columns for each of the different operators. The purpose of a gang process chart is to determine if the interaction between the workers is efficient and coordinated.

The most detailed form of job analysis is motion study, the study of the individual human motions used in a task. The purpose of motion study is to make sure that a job task does not include any unnecessary motion by the worker and to select the sequence of motions that ensure that the task is being performed in the most efficient way.

• Motion study: used to ensure efficiency of motion in a job.

Motion study originated with Frank Gilbreth, a colleague of F. W. Taylor's at the beginning of the twentieth century. F. W. Taylor's approach to the study of work methods was to select the best worker among a group of workers and use that worker's methods as the standard by which other workers were trained. Alternatively, Gilbreth studied many workers and from among them picked the best way to perform each activity. Then he combined these elements to form the "one best way" to perform a task.

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth developed motion study.

Gilbreth and his wife Lillian used movies to study individual work motions in slow motion and frame by frame, called micromotion analysis. Using motion pictures, the Gilbreths carefully categorized the basic physical elements of motion used in work.

The Gilbreths' research eventually evolved into a set of widely adopted principles of motion study, which companies have used as guidelines for the efficient design of work. These principles are categorized according to the efficient use of the human body, the efficient arrangement of the workplace, and the efficient use of equipment and machinery. The principles of motion study include about 25 rules for conserving motion. These rules can be grouped in the three categories shown in Table 8.3.

Principles of motion study: guidelines for work design.

Table 8.3. Summary of General Guidelines for Motion Study

Efficient Use of the Human Body

|

Motion study and scientific management complemented each other. Motion study was effective for designing the repetitive, simplified, assembly-line-type jobs characteristic of manufacturing operations. Frank Gilbreth's first subject was a bricklayer; through his study of this worker's motions, he was able to improve the bricklayer's productivity threefold. However, in Gilbreth's day, bricklayers were paid on the basis of how many bricks they could lay in an hour in a piecerate wage system. Who would be able to find a bricklayer today paid according to such a system!

Pioneers in the field of operations management.

There has been a movement away from task specialization and simple, repetitive jobs in lieu of greater job responsibility and a broader range of tasks, which has reduced the use of motion study. Nevertheless, motion study is still employed for repetitive jobs, especially in service industries, such as postal workers in mailrooms, who process and route thousands of pieces of mail.

The Gilbreths, together with F. W. Taylor and Henry Gantt, are considered pioneers in operations management. The Gilbreths' use of motion pictures is still popular today. Computer-generated images are used to analyze an athlete's movements to enhance performance, and video cameras are widely used to study everything from surgical procedures in the operating room to telephone operators.

A learning curve, or improvement curve, is a graph that reflects the fact that as workers repeat their tasks, they will improve performance. The learning curve effect was introduced in 1936 in an article in the Journal of Aeronautical Sciences by T. P. Wright, who described how the direct labor cost for producing airplanes decreased as the number of planes produced increased. This observation and the rate of improvement were found to be strikingly consistent across a number of airplane manufacturers. The premise of the learning curve is that improvement occurs because workers learn how to do a job better as they produce more and more units. However, it is generally recognized that other production-related factors also improve performance over time, such as methods analysis and improvement, job redesign, retooling, and worker motivation.

• Learning curve: illustrates the improvement rate of workers as a job is repeated.

As workers produce more items, they become better at their jobs.

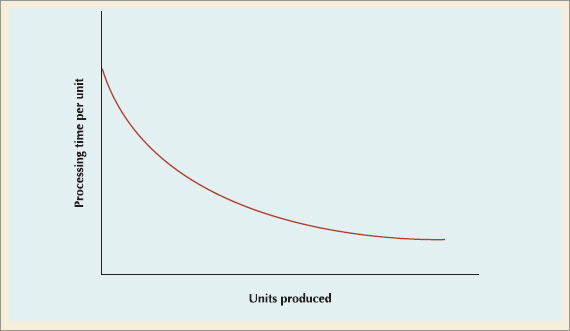

Figure 8.4 illustrates the general relationship defined by the learning curve; as the number of cumulative units produced increases, the labor time per unit decreases. Specifically, the learning curve reflects the fact that each time the number of units produced doubles, the processing time per unit decreases by a constant percentage.

The decrease in processing time per unit as production doubles will normally range from 10 to 20%. The convention is to describe a learning curve in terms of 1, or 100%, minus the percentage rate of improvement. For example, an 80% learning curve describes an improvement rate of 20% each time production doubles, a 90% learning curve indicates a 10% improvement rate, and so forth.

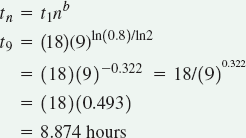

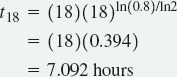

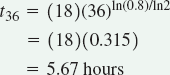

The learning curve in Figure 8.4 is similar to an exponential distribution. The corresponding learning curve formula for computing the time required for the nth unit produced is

where

tn = the time required for the nth unit produced

t1 = time required for the first unit produced

n = the cumulative number of units produced

b = ln r/ln 2, where r is the learning curve percentage (decimal coefficient)

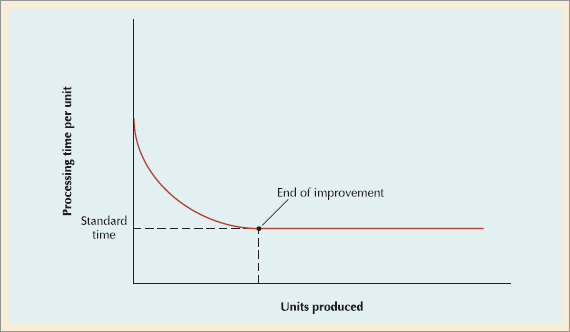

Learning curves are useful for measuring work improvement for nonrepetitive, complex jobs requiring a long time to complete, such as building airplanes. For short, repetitive, and routine jobs, there may be little relative improvement, and it may occur in a brief time span during the first (of many) job repetitions. For that reason, learning curves can have limited use for mass production and assembly-line-type jobs. A learning curve for this type of operation sometimes achieves any improvement early in the process and then flattens out and shows virtually no improvement, as reflected in Figure 8.5.

Learning curves are not effective for mass production jobs.

Learning curves help managers project labor and budgeting requirements in order to develop production scheduling plans. Knowing how many production labor hours will be required over time can enable managers to determine the number of workers to hire. Also, knowing how many labor hours will eventually be required for a product can help managers make overall product cost estimates to use in bidding for jobs and later for determining the product selling price. However, product or other changes during the production process can negate the learning curve effect.

Advantages of learning curves: planning labor, budget, and scheduling requirements.

Although learning curves can be applied to many different businesses, its impact is most pronounced in businesses and industries that include complex, repetitive operations where the work pace is determined mostly by people, not machines. Examples of industries where the learning curve is used extensively include aerospace, electronics, shipbuilding, construction, and defense. The learning curve in the aerospace and shipbuilding industries is estimated to be 85%, while it is estimated to be 90% to 95% in the electronics industry. NASA, for example, uses the learning curve to estimate costs of space shuttle production and the times to complete tasks in space.

Limitations of learning curves: product modifications negate lc effect, improvement can derive from sources besides learning, industry-derived lc rates may be inappropriate.

Aircraft manufacturers have long relied on learning curves for production planning. Learning curves were .rst recognized in the aircraft industry in 1936 by T. P. Wright. Aircraft production at that time required a large amount of direct labor for assembly work; thus any marked increases in productivity were clearly recognizable. Based on empirical analysis, Wright discovered that on average when output doubled in the aircraft industry, labor requirements decreased by approximately 20%; that is, an 80% learning curve. During World War II when aircraft manufacturing proliferated, the learning curve became a tool for planning and an integral part of military aircraft contracts. Studies during these years demonstrated the existence of the learning curve in other industries as well. For example, studies of historical production .gures at Ford Motor Company from 1909 to 1926 showed productivity improved for the Model T according to an 86% learning curve. The learning curve effect was subsequently shown to exist not only in labor-intensive manufacturing but also in capital-intensive manufacturing industries such as petroleum re.ning, steel, paper, construction, electronics and apparel, as well as in clerical operations.

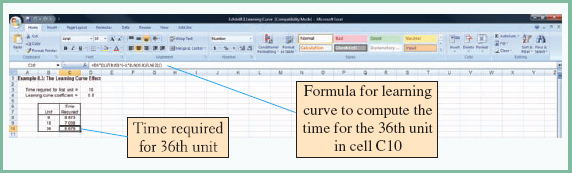

The Excel spreadsheet for Example 8.3 is shown in Exhibit 8.1. Notice that cell C8 is high-lighted and the learning curve formula for computing the time required for the 9th unit is shown on the toolbar at the top of the screen. This formula includes the learning curve coefficient in cell D4, the time required for the first unit produced in cell D3, and the target unit in B8.

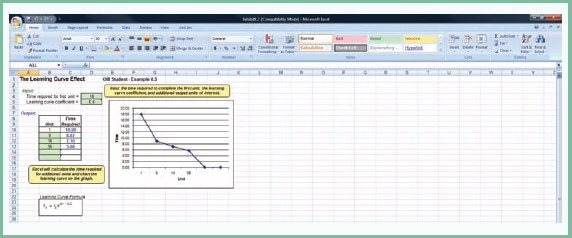

Exhibit 8.2 shows the OM Tools spreadsheet for the learning curve in Example 8.3. Note that to determine the time required for a specific unit the unit number must first be input in cells B11 to B13.

As with many other areas in production and operations management, the quality movement and increased international competition have had a dramatic impact on human resources. Traditional approaches to work in the United States that once focused on task specialization, simplification, and repetition are being supplanted by approaches that promote higher job skill levels, broader task responsibility, more worker involvement, and, most importantly, worker responsibility for quality. A number of U.S. manufacturing and service firms have attempted to adopt new approaches to human resources management.

alternative workplace a combination of nontraditional work locations, settings and practices that supplements or replaces the traditional office.

cross training an employee learns more than one job in the organization.

empowerment the authority and responsibility of the workers to alert management about job-related problems.

ergonomics the application of human sciences like anatomy, physiology, and psychology to the design of the work environment and jobs, and objects and equipment used in work; fitting the task to the person.

flextime a work schedule in which fixed times of arrival and departure are replaced by a combination of fixed and variable times.

gainsharing an incentive plan that includes employees in a common effort to achieve a company's objectives in which they share in the gains.

horizontal job enlargement the scope of a job that includes all tasks necessary to complete a product or process.

job a defined set of tasks that comprise the work performed by employees that contributes to the production of a product or delivery of a service.

job rotation the horizontal movement between two or more jobs according to a plan or schedule.

learning curve a graph that reflects the improvement rate of workers as a job is repeated and more units are produced.

managing diversity includes education, awareness, communication, fairness, and commitment.

motion study the study of the individual human motions used in a task.

motivation a willingness to work hard because that effort satisfies an employee need.

process flowchart a flowchart that illustrates, with symbols, the steps for a job or how several jobs fit together within the flow of the production process.

profit sharing the company sets aside a portion of profits and distributes it among employees usually at the end of the fiscal year.

tasks individual, defined job activities that consist of one or more elements.

telecommuting employees work electronically from whatever location they choose, either exclusively or some of the time.

vertical job enlargement the degree of self-determination and control allowed workers over their own work; also referred to as job enrichment.

worker-machine chart a chart that illustrates on a time scale the amount of time an operator and a machine are working or are idle in a job.

1. LEARNING CURVE

A military contractor is manufacturing an electronic component for a weapons system. It is estimated from the production of a prototype unit that 176 hours of direct labor will be required to produce the first unit. The industrial standard learning curve for this type of component is 90%. The contractor wants to know the labor hours that will be required for the 144th (and last) unit produced.

SOLUTION

Determine the time for the 144th unit.

8-1. Discuss how human resources might affect a company's strategic planning process.

8-2. Why has "human resources" become popular in recent years?

8-3. Describe the characteristics of job design according to the scientific management approach.

8-4. Describe the contributions of F. W. Taylor and the Gilbreths' to job design and analysis, and work measurement.

8-5. Explain the difference between horizontal and vertical job enlargement and how these concepts might work at a business like McDonalds or Starbucks.

8-6. What is the difference between tasks, elements, and motions in a basic job structure?

8-7. How did the development of the assembly-line production process at Ford Motor Company popularize the scientific management approach to job design?

8-8. The principles of scientific management were not adopted in Japan during the first half of the twentieth century as they were in the United States and other Western nations. Speculate as to why this occurred.

8-9. Contrast the traditional U.S. approaches to job design with current trends.

8-10. What are the advantages of the scientific management approach to job design (specifically, task specialization, simplicity, and repetition) to both management and the worker?

8-11. Describe the primary characteristics of the behavioral approach to job design.

8-12. How has the increased emphasis on quality improvement affected human resources management in the United States?

8-13. How successful have companies in the United States been in adapting new trends in job design that mostly have originated in Japan?

8-14. Describe the three major categories of the elements of job design.

8-15. Describe the differences between a process flowchart and a worker-machine chart and what they are designed to achieve.

8-16. Pick an activity you are familiar with in your daily life such as washing a car, cutting grass, or taking a shower and develop a process flowchart for it.

8-17. Describe some of the advantages and disadvantages of telecommuting from both the employee and manager's perspective.

8-18. Why is empowerment a critical element in total quality management? What are the disadvantages of empowerment?

8-19. Select an article (or articles) from HR Magazine and write a report on a human resource management application in a company similar to the Along the Supply Chain boxes in this chapter.

8-20. Go to the Malcolm Baldrige Web site at http://www.quality.nist.gov and write a brief report on the role of human resource management at a Baldrige award-winning company or organization.

8-21. Select a workplace at your university such as an academic department office, the athletic department, the bookstore and the cafeteria, and describe the compensation program for rank-and-file employees and any additional programs used to create job satisfaction and motivate employees. Also indicate the amount and type of job training and the involvement of employees in quality management. Identify any problems you see in the workplace environment and how it might be approved.

8-22. Describe a job you have had in the past or a job you are very familiar with and indicate the negative aspects of the job and how it could be improved with current human resource management techniques.

8-23. For what type of jobs are learning curves most useful?

8-24. What does a learning curve specifically measure?

8-25. Discuss some of the uses and limitations of learning curves.

8-1. The United Mutual and Accident Insurance Company has a large pool of clerical employees who process insurance application forms on networked computers. When the company hires a new clerical employee, it takes that person about 48 minutes to process a form. The learning curve for this job is 88%, but no additional learning will take place after about the 100th form is processed. United Mutual has recently acquired a smaller competitor that will add 800 new forms per week to its clerical pool. If an employee works six hours per day (excluding breaks, meals, and so on) per five-day week, how many employees would be hired to absorb the extra workload?

8-2. Professor Cook teaches operations management at State University. She is scheduled to give her class of 35 students a final exam on the last day of exam week, and she is leaving town the same day. She is concerned about her ability to finish grading her exams. She estimates that with everything else she has to do she has only five hours to grade the exams. From past experience she knows the first exam will take her about 12 minutes to grade. She estimates her learning curve to be about 90%, and it will be fully realized after about 10 exams. Will she get the exams graded on time?

8-3. Nite-Site, Inc., manufactures image intensification devices used in products such as night-vision goggles and aviator's night-vision imaging systems. The primary customer for these products is the U.S. military. The military requires that learning curves be employed in the bid process for awarding military contracts. The company is planning to make a bid for 120 image intensifiers to be used in a military vehicle. The company estimates the first unit will require 80 hours of direct labor to produce. The industry learning curve for this particular type of product is 92%. Determine how many hours will be required to produce the 60th and 120th units.

8-4. Jericho Vehicles manufactures special-purpose all-terrain vehicles primarily for the military and government agencies in the United States and for foreign governments. The company is planning to bid on a new all-terrain vehicle specially equipped for desert military action. The company has experienced an 87% learning curve in the past for producing similar vehicles. Based on a prototype model, it estimates the first vehicle produced will require 1600 hours of direct labor. The order is for 60 all-terrain vehicles. Determine the time that will be required for the 30th and 60th units.