MAINTENANCE OF ACCOUNTING INTERNAL CONTROLS (STUDY OBJECTIVE 10)

Much of the early part of this chapter focused on the nature and sources of fraud. Understanding fraud makes it easier to recognize the need for policies and procedures that protect an organization. Internal control systems provide this framework for fighting fraud. However, attempting to prevent or detect fraud is only one of the reasons that an organization maintains a system of internal controls.

The objectives of an internal control system are as follows:

- Safeguard assets (from fraud or errors).

- Maintain the accuracy and integrity of the accounting data.

- Promote operational efficiency.

- Ensure compliance with management directives.

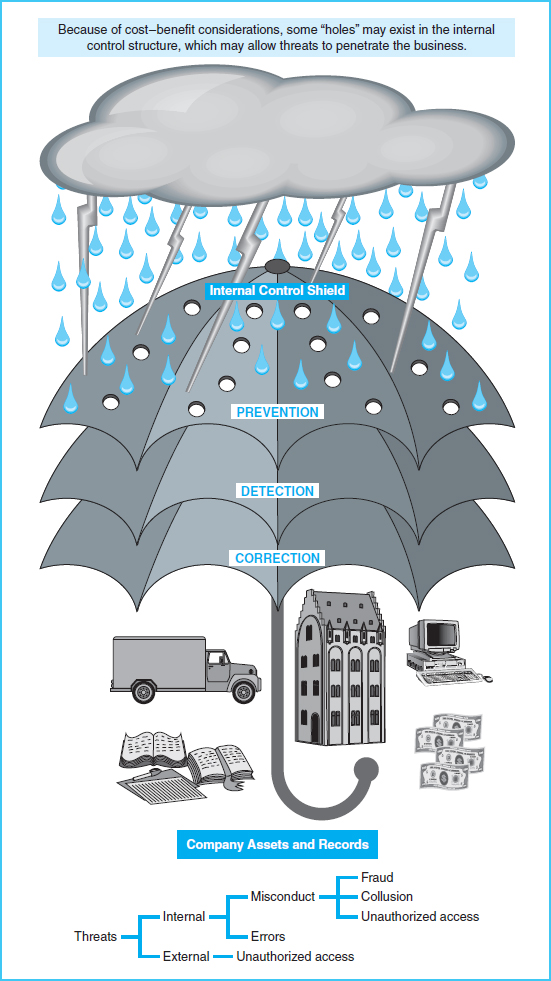

To achieve these objectives, management must establish an overall internal control system, the concept of which is depicted in Exhibit 3-4. This control system includes three types of controls. Preventive controls are designed to avoid errors, fraud, or events not authorized by management. Preventive controls intend to stop undesirable acts before they occur. For example, keeping cash locked in a safe is intended to prevent theft. Since it is not always possible to prevent all undesirable events, detective controls must be included in an internal control system. Detective controls help employees to uncover or discover errors, fraud, or unauthorized events. Examples of detective controls include matching physical counts to inventory records, reconciling bank statements to company records, and matching an invoice to its purchase order prior to payment. When these types of activities are conducted, it becomes possible to detect problems that may exist. Finally, corrective controls are those steps undertaken to correct an error or problem uncovered via detective controls. For example, if an error is detected in an employee's time card, there must be an established set of steps to follow to assure that it is corrected. These steps would be corrective controls.

Exhibit 3-4 Internal Controls as Shields to Protect Assets and Records

Any internal control system should have a combination of preventive, detective, and corrective controls. As an example, refer back to the situation presented earlier in this chapter involving the movie-theater agent who stole a customer's cash and allowed the customer to enter the theater without a ticket. The movie theater could protect itself from losses due to this type of fraud by implementing a combination of preventative, detective, and corrective controls such as the following:

- A separate ticket taker could be employed who would allow access to the theater only to those customers who present a valid ticket (preventative control).

- An automated system could be used whereby tickets are dispensed only when payment is received and recorded (detective control).

- Theater agents could be required to reconcile activities at the end of their shifts, such as comparing payments received with the number of tickets sold and the number of occupied seats in the theater (detective control).

- Procedures could be implemented to require that records are adjusted for the effect of any errors found in the system, and employees are held responsible for discrepancies found during their shifts (corrective control).

If these kinds of controls were in place, fraud occurrences would be reduced, because it is more likely that fraud would be disallowed by the system, spotted by employees, or rectified before any perpetrator could carry out the act. However, even with an extensive set of preventive, detective, and corrective controls, there are still risks that errors or fraud may occur. The idea that the internal control system cannot prevent, detect, and correct all risks is illustrated by the holes in the umbrella in Exhibit 3-4.

It is not possible to close all of the holes (or eliminate all of the risks) for many reasons. There will always be weak areas, or holes in the umbrellas because of human error, human nature, and the fact that it may not be cost effective to close all of the holes. The following sections describe the details of internal controls and the risk exposures, or holes, in those internal controls.

THE DETAILS OF THE COSO REPORT

Due to ongoing problems with fraudulent financial reporting, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) undertook a comprehensive study of internal control and in 1992 issued the Internal Control Integrated Framework, commonly known as the COSO report. The COSO report has provided the standard definition and description of internal control accepted by the accounting industry. The framework has been updated and expanded in 2012 to provide various clarifications and enhancements to its internal control guidance. According to the COSO report, there are five interrelated components of internal control: the control environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring. Each of these components is discussed next.

Control Environment

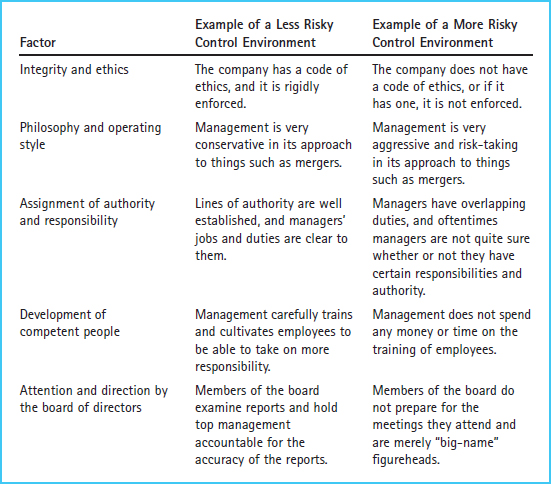

The control environment sets the tone of an organization and influences the control consciousness of its employees. The control environment is the foundation for all other components of internal control, and it provides the discipline and structure of all other components. Control environment factors include the following:

- The integrity and ethical values of the entity's people

- Management's oversight responsibility, including its philosophy and operating style

- The way management establishes structure and assigns authority and responsibility

- The way management develops its people and demonstrates commitment to competence

- The attention and direction provided by the board of directors

In each of these areas, management could establish an operating style that is either risky or more conservative. Exhibit 3-5 shows characteristics of internal control environments that are considered more risky and less risky. These examples are not intended to indicate that a company with characteristics such as those in the right-hand, “more risky” column will always experience fraud. It implies only that companies represented in the right-hand column are more likely to experience fraud because of risks in the control environment. Conversely, companies with characteristics such as those in the “less risky” column are less likely to experience fraud, because they are more conservative in their approach to the establishment of a control environment; in others words, these companies tend to play it safe by implementing protective measures.

The philosophy and operating style of management is evident in how it approaches the operation and growth of its company. For example, some managers are very aggressive in setting high earnings targets, in developing new products or markets, or in acquiring other companies. Such companies may reward management with incentive compensation plans that award bonuses for increased earnings. Management, therefore, has more motivation to be aggressive in achieving earnings growth. In this environment where aggressive growth is sought, there can be pressure to “fudge the numbers” to achieve those targets.

The operating environments as described previously are established by top management. A company's CEO can either encourage or discourage risky behaviors. Thus, the tone at the top flows through the whole organization and affects behavior at every level. For this reason, the control environment established by management is a very critical component of an internal control system. COSO identifies the tone set by management as the most important factor related to providing accurate and complete financial reports. The control environment is the foundation upon which the entire internal control system rests. No matter how strong the remaining components are, a poor control environment is likely to allow fraud or errors to occur in an organization.

Exhibit 3-5 Factors of the Control Environment

Risk Assessment

Every organization continually faces risks from external and internal sources. These risks include factors such as changing markets, increasing government regulation, and employee turnover. Each of these can cause drastic changes in the day-to-day operations of a company by disrupting routines and processes in the company, including those processes that should help prevent or detect fraud and errors. In order for management to maintain control over these threats to its business, it must constantly be engaged in risk assessment, whereby it considers existing threats and the potential for additional risks and stands ready to respond should these events occur. Management must develop a systematic and ongoing way to do the following:

- Specify the relevant objectives of the risk assessment process.

- Identify the sources of risks (both internal and external, and due to both fraud or error), and determine the impact of such risks in terms of finances and reputation.

- Identify and analyze significant changes in the business.

- Develop and execute an action plan to reduce the impact and probability of these risks.

Control Activities

The COSO report identifies control activities as the policies and procedures that help ensure that management directives are carried out and that management objectives are achieved. A good internal control system must include control activities that occur at all levels and in all functions within the company, including controls over technology. The control activities include a range of actions that should be deployed through the company's policies and procedures. These activities can be divided into the following categories:

- Authorization of transactions

- Segregation of duties

- Adequate records and documents

- Security of assets and documents

- Independent checks and reconciliations

Authorization of Transactions In any organization, it is important to try to ensure that the organization engage only in transactions which are authorized. Authorization refers to an approval, or endorsement, from a responsible person or department in the organization that has been sanctioned by top management. Every transaction that occurs must be properly authorized in some manner. For example, some procedure should be followed to determine when it is allowable to purchase goods, or when it is permissible to extend credit. A common example that you may have encountered occurs at some grocery and department stores. If you have ever stood in a long checkout line while the shopper in front tried to pay with an out-of-state check, you probably groaned silently, knowing that the line would be further delayed while the check-out clerk waited for a manager to approve the payment method. Notice that in this example, for the transaction that carries extra risk (the possibility of a bounced out-of-state check), the company has established a procedure to discourage bad check–writing. This procedure is the requirement for a specific authorization from a manager before the transaction can be completed.

The preceding example also helps illustrate the difference between specific authorization and general authorization. General authorization is a set of guidelines that allows transactions to be completed as long as they fall within established parameters. In the example of a grocery or department store, the established guidelines are that the checkout clerk can process anyone through the line as long as the customer pays by cash, credit card, debit card, or an in-state check. If any customer is an exception to these payment methods, as in the case of an out-of-state check, the transaction requires specific authorization. Specific authorization means that explicit approval is needed for that single transaction to be completed.

Another example of the difference between these two types of authorization can be seen in the procedures that a company uses when making purchases. Management usually has established reorder points for inventory items, and when inventory quantities drop to that predetermined level, purchasing agents have general authority to initiate a purchase transaction. However, if the company needs to purchase a new fleet of vehicles, for instance, a specific authorization from upper-level management is likely to be required.

Any organization should establish and maintain clear, concise guidance as to procedures that fall under general authorization as opposed to those requiring specific authorization. Not only does such a practice assure that all transactions are properly authorized; it also makes the organization more efficient. In our example of a grocery store, the checkout line can move quickly and efficiently for low-risk transactions involving payment by cash, credit card, debit card, or in-state check. However, when high-risk transactions are encountered, the extra risk warrants a brief inefficiency (the slowdown in the line) to assure that the risk is controlled by a specific authorization. Another important aspect is that the employee must be well trained and must understand when this specific authorization is needed.

In summary, a part of the control procedures is the guidelines regarding general and specific authorization. Top managers must appropriately delegate the authorization of transactions and establish authorization procedures and practices to assure that the guidelines are followed. They must ascertain that managers and employees have been trained to understand and carry out these policies and practices.

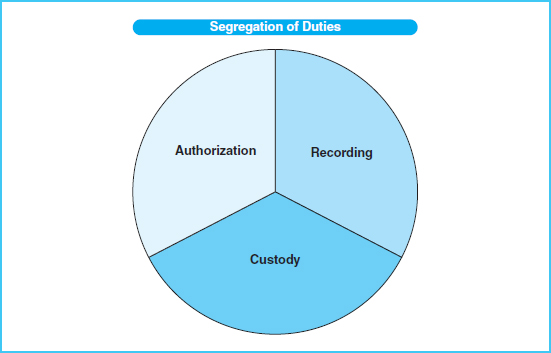

Segregation of Duties When management delegates authority and develops guidelines as to the use of that authority, it must assure that the authorization is separated from other duties. This separation of related duties is called segregation of duties. For any transaction, there are usually three component parts: authorization of the transaction, recording the transaction, and custody of the related asset(s). Ideally, management should separate these three components by assigning each component to a different person or department within the organization. The person or department authorizing a transaction should neither be responsible for recording it in the accounting records nor have custody of the related asset. To understand the possible effect of not segregating these duties, consider a payroll example. If a foreman were allowed to hire employees, approve their hours worked, and also distribute the paychecks, then authorization would not have been segregated from custody of the checks. This would give a dishonest foreman the perfect opportunity to make up a fictitious employee and collect the paycheck. However, if paychecks were distributed to employees by someone other than the foreman, the opportunity for this kind of payroll theft would be reduced.

When it is reasonably possible to do so, all three components—authorization, recording, and custody—should be segregated. Exhibit 3-6 illustrates this segregation of duties.

It may not always be possible or reasonable to segregate all three components. This is especially true in small organizations where there may not be enough workers to adequately segregate. However, in smaller companies there is usually much closer supervision by the owner or manager, which helps compensate for the lack of segregation. Thus, supervision is a compensating control that lessens the risk of negative effects when other controls are lacking. Supervision as a compensating control is appropriate in larger organizations, too, where there may be situations in which it is difficult to fully segregate duties.

Adequate Records and Documents When management is conscientious and thorough about preparing and retaining documentation in support of its accounting transactions, internal controls are strengthened. Accounting documents and records are important, because they provide evidence and establish responsibility.

Exhibit 3-6 Segregation of Duties

In general, a good system of internal controls includes the following types of documentation:

- Supporting documentation for all significant transactions, including orders, invoices, contracts, account statements, shipping and receiving forms, and checks. Whenever possible, original documentation should be retained as verification of authenticity. Specific types of documentation are discussed in subsequent chapters within the presentations of the various business processes.

- Schedules and analyses of financial information, including details of account balances; reconciliations; references; comparisons; and narrative explanations, comments, and conclusions. These documents should be independently verified from time to time in order for their accuracy to be assessed.

- Accounting cycle reports, including journals, ledgers, subledgers, trial balances, and financial statements.

Documents and records provide evidence that management's policies and procedures, including internal control procedures, are being carried out. They also provide an audit trail, which presents verifiable information about the accuracy of accounting records. If accurate, sufficient documentation is maintained, then an audit trail can be established, which can re-create the details of individual transactions at each stage of the business process in order to determine whether proper accounting procedures for the transaction were performed.

All paper documentation should be signed or initialed by the person(s) who authorized, recorded, and/or reviewed the related transactions. This practice establishes responsibility within the accounting function. When records are maintained in electronic format, the organization should take steps to control access to the related files and ensure that adequate backup copies are available in order to reduce the risk of alteration, loss, or destruction. In a computerized system, the audit trail usually includes a detailed transaction log, because the computer system automatically logs each transaction and the source of the transaction. In today's business world, where many records are maintained within computerized systems, managers and auditors must understand, access, and control those accounting records maintained within an electronic environment.

In addition to accounting documents and reports, business organizations should maintain thorough documentation on their policies and procedures. In order to provide clarity and promote compliance within the organization, both manual and automated processes and control procedures should be formalized in writing and made available to all responsible parties.

Security of Assets and Documents Organizations should establish control activities to safeguard their assets, documents, and records. These control activities involve securing and protecting assets and records so that they are not misused or stolen. In the case of assets, physical protection requires limiting access to the extent that is practical. For example, cash must be on hand for a company to operate, but this cash can be locked in safes or cash registers until needed. Assets such as inventory should be protected by physical safeguards such as locks, security cameras, and restricted areas requiring appropriate ID for entry.

In addition to physical safeguards of assets, it is also important to limit access to documents and records. Unauthorized access or use of documents and records allows the easy manipulation of those documents or records, which can result in fraud or cover-up of theft. For example, unauthorized access to blank checks can lead to fraudulent checks being written. All blank documents must be controlled by limiting access to only those who require access as part of their job duties.

In both cases—protecting physical assets and protecting information—there is a trade-off between limited access and efficiency. The more access is limited, the harder it becomes to do a job efficiently. This is why controls must have a benefit greater than their cost. For example, a company could have all employees searched as they leave at the end of their shifts in order to discourage inventory theft. However, the cost of this intrusion in terms of its impact on employee morale and turnover may be greater than the savings from theft avoidance. This concept of the cost–benefit comparison of controls is discussed later in the chapter in terms of reasonable assurance.

Independent Checks and Reconciliation Independent checks on performance are an important aspect of control activities. Independent checks serve as a method to confirm the accuracy and completeness of data in the accounting system. While there are many procedures that accomplish independent checks, examples are as follows:

- Reconciliation

- Comparison of physical assets with records

- Recalculation of amounts

- Analysis of reports

- Review of batch totals

An example of each of these independent checks on performance follows. A reconciliation is a procedure that compares records from different sources. For instance, a bank reconciliation compares independent bank records with company records to ensure the accuracy and completeness of cash records. Similarly, a comparison of physical assets with records occurs when a company takes a physical count of inventory and compares the results to the inventory records. Any differences are recorded as adjustments to inventory and result in correct inventory records. Recalculation of amounts can help uncover math or program logic errors. For example, recalculating price times quantity may uncover errors in invoices that were caused by either human error or bad program logic. Analysis of reports is the examination of a report to assess the accuracy and reliability of the data in that report. A manager who regularly reviews reports is likely to notice errors that crop up in the reports; the manager may not always notice such errors, but many times will. Finally, review of batch totals is an independent check to assure the accuracy and completeness of transactions processed in a batch. Batch processing occurs when similar transactions are grouped together and processed as a group. For example, time cards can be collected from all employees within a department and processed simultaneously as a batch. In batch processing, it is possible to calculate a batch total, which is merely a summation of key items in the batch (such as hours worked), and compare this batch total along various stages of processing. If at some stage of processing the batch totals no longer match, this means that an error has occurred in processing.

These descriptions of independent checks are examples of control activities, but they only scratch the surface of the number and types of independent checks that may be necessary in an organization. Such independent checks can serve as both detective and preventative controls. They are detective in that they uncover problems in data or processing; they are preventive in the sense that they may help discourage errors and fraud before they occur. For example, employees know that when a company regularly takes a physical inventory and compares the counts with records, shortages are more likely to come to light. Therefore, employees may be less likely to steal inventory, because they presume they will get caught. This preventive effect becomes more obvious if you consider the opposite environment, in which a company never takes a physical inventory. When employees know this, they recognize that it would be easier to carry out a fraudulent act without getting caught.

Information and Communication

To assess, manage, and control the efficiency and effectiveness of operations of an organization, management must have access to feedback information and reports. The feedback consists of operational and financial information, much of it generated by the accounting system. An effective accounting system will provide accurate and complete feedback. Therefore, the better the accounting system, the better management can assess and control operations.

The entire accounting system is therefore a very important component of the internal control system. An ineffective accounting system can generate inaccurate or incomplete reports, and this leads to more difficulty in properly controlling activities. An effective accounting system must accomplish the following objectives:

- Identify all relevant financial events (transactions) of the organization.

- Capture the important data of these transactions.

- Record and process the data through appropriate classification, summarization, and aggregation.

- Communicate this summarized and aggregated information as needed for internal and external purposes.

Whether an accounting system is manual or computerized, it must achieve these objectives to be effective. In addition to maintaining an effective accounting system, the entity must implement procedures to assure that the information and reports are communicated to the appropriate management level. The COSO report describes this communication as “flowing down, across, and up the organization.” Such a flow of communication assists management in properly assessing operations and making changes to operations as necessary.

MONITORING

Any system of control must be constantly monitored to assure that it continues to be effective. Monitoring involves the ongoing review and evaluation of the system. For example, your home may have a heating system with a thermostat. The thermostat constantly measures temperature and turns the heat on or off to maintain the desired temperature. Thus, the thermostat is a control system. However, due to wear and tear or other changes, the thermostat and heater may begin to malfunction. To keep them operating at peak effectiveness, there must be periodic checks on the thermostat and heating system to make sure they are working correctly. The same is true of an internal control system in an organization. To keep the controls operating effectively, management must monitor the system and attempt to improve any deficiencies encountered. This is especially important as organizations undergo changes. Employee and management turnover, new business processes or procedures, and market changes may all affect the functionality of internal controls.

There are many ways an organization can monitor its internal control system. To be most effective, both continuous and periodic monitoring should take place. As managers carry out their regular duties of examining reports, they are performing a type of continuous monitoring. Management should notice major weaknesses or breakdowns in internal controls as they accomplish their duties. In computerized systems, there may be continuous monitoring within the system itself. That is, the computerized accounting system may include modules within the software that review the system on an ongoing basis. In addition, some monitoring, such as internal and external audits, occurs on a regular periodic basis. These audits include examinations of the effectiveness of internal controls. As weaknesses or problems are uncovered through continuous and periodic monitoring, these issues must be reported to management to allow for appropriate evaluation and correction.

All five internal control components prescribed by the COSO report are necessary for the establishment and maintenance of a capable system of internal controls. The control environment, risk assessment procedures, control activities, information and communication processes, and ongoing monitoring of the system each play a part in strengthening the overall system. There is an old saying that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. This is also true of the five components of internal control. If any one of the five is weak, the entire system of internal controls will be weak. Much as the links of a chain work together, these components work together to make an effective control system.

REASONABLE ASSURANCE OF INTERNAL CONTROLS

A company that is well managed will maintain a good system of internal controls because to do so makes good business sense. An appropriate internal control system can help an organization achieve its objectives. However, there are limits to what an internal control system can accomplish. Internal controls provide reasonable assurance of meeting the control objectives. Reasonable assurance means that the controls achieve a sensible balance of reducing risk when compared with the cost of the control. It is not possible for an internal control system to provide absolute assurance, because there are factors that limit the effectiveness of controls, such as the following:

- Flawed judgments are applied in decision making.

- Human error exists in every organization.

- Controls can be circumvented or ignored.

- Controls may not be cost beneficial.

No matter how well an internal control system is designed, it is limited by the fact that humans sometimes make erroneous judgments and simple errors or mistakes. Even when a person has good intentions, an error in judgment or a mistake, such as simply forgetting to do a step that provides an internal control, can cause harm. For example, it would be easy for a supervisor to simply forget to sign time cards for a particular pay period.

Another limit to the effectiveness of internal controls is that they can be circumvented. One way to circumvent internal controls is through collusion. Two people working together can thwart internal control procedures. For example, assume that one employee prepares time cards and a second employee distributes paychecks. Working alone, the first employee cannot easily make up a fake employee, submit a fake time card, and get access to the resulting paycheck. But if these two employees agree to work together and split the resulting paycheck, it would be very difficult to prevent. In this example, collusion negates the control effect of segregation of duties.

For every control procedure that an organization wishes to use, the benefits must outweigh the costs. Benefits can be measured by the positive effect the control has. If a control reduces the chance of errors, then an assessment could be made of the savings that would result from lower errors. The cost of the control procedure can be monetary or measured in terms of reduced operating efficiency. For example, a control procedure that requires all purchase transactions of any size to be approved by the CEO would dramatically slow the pace of purchasing. The CEO's desk would become a bottleneck of purchase requests waiting to be approved. This approval procedure would not be cost-effective. However, it may be cost-effective to have the CEO approve only those purchases involving very large dollar amounts, or highly unusual orders. Before adoption, every control procedure should be analyzed to be sure that it results in benefits that exceed the costs of implementing the control.