PHASES OF AN IT AUDIT (STUDY OBJECTIVE 6)

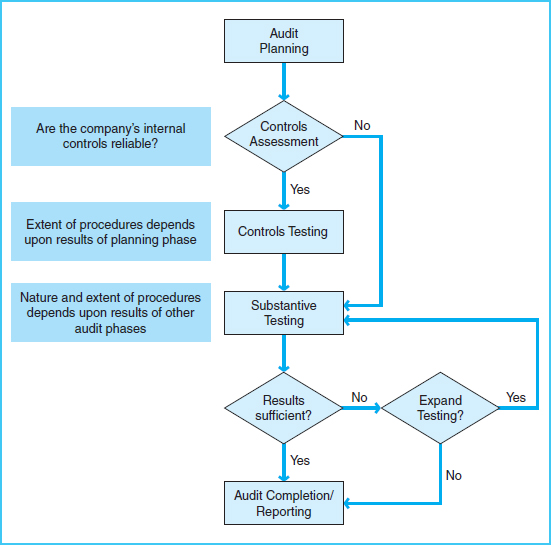

An IT audit generally follows the same pattern as a typical financial statement audit. There are four primary phases of the audit: planning, tests of controls, substantive tests, and audit completion/reporting. Exhibit 7-4 provides an overview of these phases.

Through each phase of an audit, evidence is accumulated as a basis for supporting the conclusions reached by the auditors. Audit evidence is proof of the fairness of financial information. The techniques used for gathering evidence include the following:

- Physically examining or inspecting assets or supporting documentation

- Obtaining written confirmation from an independent source

- Reperforming tasks or recalculating information

- Observing the underlying activities

- Making inquiries of company personnel

- Analyzing financial relationships and making comparisons to determine reasonableness

The various phases of the audits typically include a combination of these techniques.

AUDIT PLANNING

During the planning phase of an audit, the auditor must gain a thorough understanding of the company's business and financial reporting systems. In doing so, auditors review and assess the risks and controls related to the business, establish materiality guidelines, and develop relevant tests addressing the assertions and objectives (presented earlier). A process map of the planning phase of the audit is presented in Exhibit 7-5.

The tasks of assessing materiality and audit risk are very subjective and are therefore typically performed by experienced auditors. In determining materiality, auditors estimate the monetary amounts that are large enough to make a difference in decision making. Materiality estimates are then assigned to account balances so that auditors can decide how much evidence is needed. Transactions and account balances that are equal to or greater than the materiality limits will be carefully tested. Those below the materiality limits are often considered insignificant (if it is unlikely that they will impact decision making) and therefore receive little or no attention on the audit. Some of these accounts with immaterial balances may still be audited, though, especially if they are considered areas of high risk. Risk refers to the likelihood that errors or fraud may occur. Risk can be inherent in the company's business (due to such things as the nature of operations, the economy, or management's strategies), or it may be caused by weak internal controls. Auditors need to perform risk assessment to carefully consider the risks and the resulting problems to which the company may be susceptible. In addition, there will always be some risk that material errors or fraud may not be discovered in an audit. Each of these risk factors and the materiality estimates are important to consider in determining the nature and extent of audit tests to be applied.

Exhibit 7-4 Process Map of the Phases of an Audit

The audit planning process is likely to vary significantly depending upon the company's financial reporting regime. If the company has adopted IFRS or is in the process of convergence, changes in the audit approach should be anticipated. In addition to obvious changes in the reporting requirements and related modifications to its IT systems, many companies' implementation of IFRS requires transformation of its business processes, policies, and controls. Moreover, adapting to fair value measures, relying on more external data, and understanding key assumptions necessary in the preparation of IFRS-based financial statements will likely cause management and auditors to evaluate supporting evidence differently than if U.S. GAAP was used. IFRS generally allows more use of judgment than GAAP's rules-based guidance; thus, a change in accounting regimes may change the decisions made by managers and by auditors.

Exhibit 7-5 Audit Planning Phase Process Map

A big part of the audit planning process is the gathering of evidence about the company's internal controls. Auditors typically gain an understanding of internal controls by interviewing key members of management and the IT staff. They also observe policies and procedures and review IT user manuals and system flowcharts. They often prepare narratives or memos to summarize the results of their findings. In addition, company personnel generally complete a questionnaire about the company's accounting systems, including its IT implementation and operations, the types of hardware and software used, and control of computer resources. The understanding of internal controls provides the basis for designing appropriate audit tests to be used in the remaining phases of the audit. Therefore, it is very important that the auditor understand how complex its clients' IT systems are and what types of evidence may be available for use in the audit.

The process of evaluating internal controls and designing meaningful audit tests is more complex for automated systems than for manual systems. Using just human eyes, an auditor cannot easily spot the controls that are part of an automated (computer) system. In recognition of the fact that accounting records and files often exist in both paper and electronic form, auditing standards address the importance of understanding both the automated and manual procedures that make up an organization's internal controls. Auditors must consider how misstatements may occur, including the following:

- How transactions are entered into the computer

- How standard journal entries are initiated, recorded, and processed

- How nonstandard journal entries and adjusting entries are initiated, recorded, and processed

IT auditors may be called upon to consider the effects of computer processing on the audit or to assist in testing those automated procedures.