HUMAN RESPONSE TO STORY 1

This chapter will focus on why we like stories and provide a storytelling primer.

Olivia could sense the growing antipathy with each passing word. “Our firm is so well-equipped to handle the design of your library,” she thought to herself. And she had good reason to; the numbers were good; they had compiled a qualified team and created a detailed action plan. They had even received several accolades for a similar project. When discussing these merits, however, she saw the board of trustees looking at their phones; some were even whispering to each other. So, she paused, and said, “Let me give you an example.” As she told her story, she could see several of the board members put down their phones, lean in, and start to listen more intently.

Her story had changed the entire mood of the room.

INTRODUCTION

Campfires, water coolers, dinner tables – storytelling occurs in many places and across many cultures. From Aesop’s Fables to the Trojan Horse, the most enduring stories are handed down from one generation to the next. In fact, many of today’s films are rooted in classic works. Skywalker’s triumph over the evil Darth Vader is likened to the hero’s journey of ancient Greek mythology. Bridget Jones’ endearing quest for love is a modern telling of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Stories can be a potent delivery tool; some even argue that they are the most powerful and enduring art form.1

Whether to a client, teacher, or supervisor, a designer’s role is often to convince another party that they hold the key to the best possible solution. So, whether we like it or not, design is steeped in the art of salesmanship – and stories can help “seal the deal.”

WHY DOES STORY MATTER IN DESIGN?

To paraphrase marketing expert Jonah Sachs, the capacity to spark change and provide inspiring solutions stems from our ability to provide great stories.2 With more ways to reach an audience, it can actually be harder to move them. The best storytellers can use their craft to cut through the distractions of everyday life. Their stories act as an affective primer, steering the emotions of their audience toward the desired course of action.

As designers of products, spaces, and experiences, we too can use the art of storytelling to shape the emotions of our audience prior to sharing our ideas. If we want to empower our client to take a radical new approach, we can share a story that calls them to action. If we want our clients to be dissuaded from making a bad decision, a story highlighting another company’s similar missteps can be a very powerful deterrent.

Stories can serve as a moral guidepost or as a quick and vivid means of sharing information, selling lifestyles, sparking change, or inspiring others.3 But to harness their power, we need to understand their potential in design communication.

DESIGN COMMUNICATION TACTICS

Since designers are called to both inform and persuade their audiences, many parallels can be drawn between design communication tactics and contemporary marketing strategies. The best marketing campaigns are thought to contain three ingredients: Meaning, Explanation, and Story.4 These ingredients help ensure that a message is relevant, understood, and captivating.

Consider these ingredients in the design communication tactics below:

| Report | Presentation | Video | |

| Goals | Notify or Update | Simplify, Clarify, or Illuminate | Illuminate or Entertain |

| Delivery | Precise & Exhaustive | Believable & Credible | Express & Introduce |

| Results | Informed Audience | Motivated Audience | Moved Audience |

| Example | Case Study | Design Presentation | Online video |

THE SCIENCE BEHIND WHY WE LIKE STORIES

Stories are often considered essential to the human experience. In fact, storyteller Kendall Haven refers to our species as Homo narratus.5 There are several theories as to why we are so drawn to stories.6

The first theory is that stories are simply a byproduct of human existence. Supporters of this premise suggest that our brains are not designed to enjoy stories, but that they are susceptible to being seduced by them. The second theory is that our attraction to stories has been ingrained in our DNA via chance evolutionary adaptations. The third theory suggests that stories were a survival tool.7 This final proposition may be surprising since stories do not outwardly seem to satisfy the fundamental needs of our hunter-gatherer ancestors (e.g., food, water, & procreation), although cave paintings suggest that our ancient ancestors used stories to recount life-altering experiences. A story about an epic hunting adventure, for example, provided lessons about which animals would make for a good dinner (and maybe even which would want them for dinner). At the same time, the storyteller likely appeared more attractive by showcasing the skills and qualities that would make for an ideal mate.

THE EVOLUTION OF STORY

Over time, stories became more complex, in turn, serving more purposes. As our societies advanced (and our survival became more secure), our stories no longer had to be grounded in facts. Our ancestors grew to love the intense drama and suspense made possible only by fictionalized stories. These stories provided entertainment and a release from the trials and tribulations of war, plague, and famine. However, even amidst the comforts of modern life, we continue to enjoy such escapes.

In fact, researchers Tooby and Cosmides asserted that our brains have a built-in reward system that attracts us to fictional experiences, even when we wouldn’t enjoy an obvious payoff.8 This may explain why, on a rainy Saturday afternoon, we may prefer to binge-watch our favorite show instead of reworking our portfolio.

However, evidence suggests that stories are more than merely tools of distraction, and research has provided some valuable insights surrounding how stories help us form social connections, organize information, and even learn right from wrong.

Figure 1.0

Stories help us form social connections, organize information, & learn right from wrong

STORIES IN BUILDING SOCIAL CONNECTIONS

We are social creatures. Belonging to something bigger than ourselves gives us purpose, and affiliation brings us comfort. Our social yearnings influence how we spend our time. We live, work, and play beside each other in families, organizations, and communities. In fact, studies have suggested that we spend 80% of our waking hours alongside other people.9 Much of this time is spent in conversation and it is estimated that we spend 6 –12 hours of each day engaged in dialogue.10 We might assume that most of these conversations focus on goal-oriented matters such as career aspirations or finances but, when studied, the content of most conversations was centered on either ourselves or specific individuals – even in professional settings like university classrooms and corporate lunches.11 We don’t discuss business proposals or learning objectives; we discuss ourselves and each other – that is to say, we gossip.

GOSSIP

While our mothers may have warned us about the dangers of gossip, they also taught us to look after each other. In a sign of fellowship, our primate cousins spend much of their day performing acts of social grooming. In other words, to show affection, they clean their friends and family. While we humans have similar goals for expressing solidity and social order, gossip frees up our hands to perform other tasks.12

Gossip has a bad reputation, but not all of it is bad. Researchers have suggested that gossip serves several purposes, allowing us to seek and share information,13 express opinions, obtain guidance, define social norms, and satisfy our desire to belong.14 In these intimate exchanges, there can be benefits for both parties. Those listening may gain newfound insight, while the teller might benefit from added stature or reciprocity. Essentially, since you shared something with me, I’ll return the favor.15

Gossip has worked so well for our species that it is considered universal across cultures.16 Whether our gossip sessions stem from factual or fictional accounts (or somewhere in between), gossip is a form of storytelling, complete with characters, conflict, and intrigue.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt said that without gossip…

“there would be chaos and ignorance.”17

FICTIONAL STORIES

Gossiping about a co-worker is not the only way story shapes our social interactions. Since fictional stories simulate social experiences, evidence suggests that they also shape how we interact with others. When researchers compared both the emotional states and personality traits of individuals who read either a story-based or factual account about the same information, readers of the story version experienced significantly greater changes in their personality traits.18 Since stories often contain vivid descriptions of a character’s mental state, they are thought to improve our social awareness too.19 Researchers found that fiction readers have greater sense of empathy,20 21 and were more attuned to the intentions and opinions of others.22

STORIES FOR ORGANIZING INFORMATION

Along with building social connections, our brains have an innate desire to organize information, and stories can help us link information into a series of events, then align those events with our own experience.

LINKING EVENTS WITH A STORY

Our mothers may have also warned us about the consequences of making assumptions, and for a good reason, since our assumptions can often be wrong. To avoid accepting incorrect ideas, our brains seek to categorize these ideas into causes and corresponding effects; this is known as causal reasoning.23 Stories can aid causal reasoning by helping the audience link a series of events rather than wrestle with disconnected anecdotes.24 Author Lisa Cron explained cause and effect with the mantra of If, Then, and Therefore.25

If there is an action,

then another event will follow;

therefore, we should either embark upon or avoid it.

As an example… if we work on our portfolio, then we might land the job; therefore, we should work on our portfolio.

LIFE LESSONS WITH IF, THEN, AND THEREFORE

Let’s say your 7-year-old niece cannot be convinced that she was wrong to poke fun at a friend’s outfit, choosing instead to project the blame on the classmate for making what she calls “a ghastly decision.” Being a good auntie or uncle, you are hoping to share with her the ill effects of vanity.

To do so, you could outline the relationship between vanity and narcissism, suggest how vanity might damage her friendships, or advise her that her comments might hurt her reputation. While such insights are rational and valid, your niece is not likely to be moved by them, much less pass down these anecdotes to her own children.

Another option would be a thoughtful retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s fable, “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” wherein the emperor’s vanity kept him from admitting that he could not see the weaver’s magical thread. The effect was that he unwittingly paraded down the streets of his kingdom, completely naked, – her lesson, admit when you are wrong.

Figure 1.1

Stories shape how we interact with others

LINKING A STORY’S EVENTS TO OUR OWN EXPERIENCE

Another way our brains attempt to understand new information is to align it with our own experiences,26 and stories have an uncanny way to help us do so. In a good story, when the main character is scared, we’re scared, when they’re triumphant, we too bask in their glory. Essentially, we share their emotions.

Our emotions are due to a chain of reactions set off in our brain. Dopamine causes our brains to anticipate the new experiences offered in the story.27 Brain scans have shown that when the characters embark on these new experiences, various regions of the brain track different aspects of the story. Some of these areas actually mirror those that would be used by the characters themselves during the story’s unfolding events; this is why we feel embarrassed when a character has an awkward conversation. We construct visual and motor representations that essentially mimic the story’s events as if we are going through them ourselves.28 This causes our brains to produce the stress hormone cortisol when our hero is struggling,29 and oxytocin when a stranger offers kindness.30 If the main character is pursuing a goal, even more regions of our brain are engaged.31 Not only can we experience our hero’s struggles and triumphs, but we can use them as a guide should we encounter a similar situation.

ORGANIZATION OPPORTUNITY

To leverage the brain’s naturally occurring chain of chemical reactions, designers can craft a story that helps their audience link events. For example, instead of discussing the merits of a floor plan, they can share a story about the experience one may have as they enter and move throughout the space. The designer weaves a story about the character’s journey, highlighting design features along the way. The audience can then link the spaces in their minds and use causal reasoning to envision how others might use those spaces. In their minds, if the space is designed this way, then building occupants might be able to experience it in this manner; therefore, this is the best design. They might even align the story with a positive event in their own lives – the effect can be quite potent.

Figure 1.2

Stories can help us link events together & to our own experiences

EXERCISE 1.0 USING STORY TO LINK EVENTS

Putting your linking skills to the test.

Look around the space you’re currently in until you see three words.

Write a paragraph-long short story that links these three words together.

STORY AS MORAL GUIDEPOST

“Human beings share stories to remind each other of who they are and how they should act.”32

Part policeman and part teacher, was how Haidt characterized the role of story in our society,33 meaning that stories represent a society’s values, along with the consequences of ignoring those values. And while we may no longer be asked to state the moral of a story, the reality is that whether they teach us to care for one another or warn us of the ills facing our society, almost all stories present us with a takeaway.

Many story morals are threaded into our everyday values. We shy away from giving false alarms for fear of crying wolf. Aesop taught us to value quality over quantity in the “Lioness and the Vixen,” and not to count our chickens before they hatch in the “Milkmaid and her Pail.” Greek mythology reminds us of our own vulnerabilities, or our Achilles heel, and even to be cautious of suspicious emails for fear of opening a Trojan horse. Such stories have been gifted to us so that we might know what would befall us if we were to follow a similar path. They prompt us to recall past experiences and what was learned from those experiences so that we can predict how others will react when facing them too.34 The best part is that we can simulate these experiences without having to actually go through them ourselves, much less the aftermath. We don’t have to be the naked emperor to learn from his missteps.

INFLUENCING OUR BELIEFS

Evidence suggests that stories can also influence how we behave.35 If we identify with a character, we may be more likely to embody their positive attributes. And these changes are thought to be relatively stable, meaning they do not change right after the story is over. In fact, researchers suggest that beliefs changed as a result of a story may even grow stronger over time.36 This insight led researchers to suggest that a story’s ability to psychologically transport an audience is a “powerful means of altering our view of the world.”37

Listening to the stories of others is not the only way they frame our values. By generating our own stories, we can describe our experiences, and in turn, better understand ourselves. Mental health professionals have long used this tactic when treating their patients. In fact, psychiatrist and author Bradley Lewis wrote that “psychiatrists listen to stories more than anything else they do.”38 So, when we gossip about a coworker, not only are we attempting to bond with colleagues, but the act itself can be cathartic.

Within design, stories can be used as a call to action or to justify ideals. For example, if a designer wants to defend a price increase following a voluntary pay raise for their apparel workers, they might tell a story about a young employee who can more easily provide for her family given the higher living wage. The key is to be authentic. If the same designer was to tell this story, but only to conceal their own self-serving goals, their message will likely fall flat. It will be delivered with less passion, conviction, and zeal. Worse yet, in time, they will likely be called out on their deception – especially given the access to information and the hyper-connectedness made possible with social media. Sachs defined these truth detectives as agents of authenticity,39 stating that once an agent of authenticity uncovers a fabrication, they share it with others, thus destroying the teller’s credibility. Stories only work if they are genuine.

ELEMENTS OF STORY

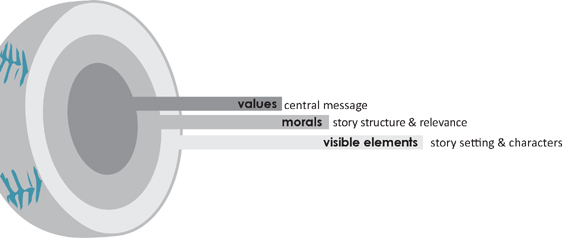

To understand why stories help the audience to connect with each other, organize information, and learn right from wrong, it’s worth exploring the elements of story. Sachs likened the structure of a story to that of a baseball, the surface of which holds the story’s visible elements, such as its setting and characters.40 Under this layer lie its morals, which provide the story’s structure and relevance. Finally, within its core, rests the values that inform it all.

We will begin our exploration at the core of the story.

Figure 1.3

Consider the structure of story as being similar to that of a baseball

VALUES

Values are central to a good story, but they can be easily misplaced and misconstrued in the commercials, advertisements, slogans, and political messages that surround us. These too are persuasive stories, and Sachs surmises they follow one of two aims: making the audience feel either inadequate or empowered.41

INADEQUACY MARKETING

Sachs attributed inadequacy marketing to Freudian drives of materialism and lust. Stories based in these values exploit a person’s anxieties by stressing their shortcomings. The only cure, of course, is the product or idea that they happen to be touting. For example, wearing label “X” will help the struggling professional finally gain the respect of their colleagues. The underlining message is that the consumer does not currently enjoy their coworkers’ respect, but the product will guarantee that respect. The moral of inadequacy marketing is that the product is the hero, and acquiring it is the only way to achieve happiness.

EMPOWERMENT MARKETING

The audience is the hero in empowerment marketing. Instead of being merely a consumer of a product or idea, Sachs suggested that the audience rises to the role of the citizen. The moral is that you can accomplish something great, and a product or idea can help you to do so. In empowerment stories, the audience rallies behind inclusive mantras such as better together, or we can. Sachs suggests this tactic is more successful. His premise is that an inspired citizen makes for a loyal evangelist for a product or idea.42 He also observed that empowerment stories tend to be shared with others far more frequently. As case in point, would you be more apt to like a video that has left you feeling inspired, or one that calls out your flaws? To understand empowerment marketing, Sachs referred to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see page 26).

Figure 1.4

Inadequacy marketing reminds consumers of their shortcomings while consumers are the hero in empowerment marketing

TYPES OF VALUES

Maslow was a psychologist who, unlike Freud, primarily studied people who were generally content with their lives. Instead of coveting items or goods, he found them seeking higher level needs, such as finding purpose or making a difference.43 Sach’s lists nine such values which can be used to frame persuasive empowerment stories.44 Your story won’t call upon all nine values doing so would only dilute your message. The key is to focus on one value that know will resonate with your audience, which will be considered in Chapter 3.

VALUE TO MORAL

The story’s moral is how its values comes to life. For instance, if the audience values justice, a designer might focus on how new production techniques provide better working conditions for their employees. The moral is that the audience should purchase from this brand because they care for their employees.

If the audience values richness, the designer might vividly narrate the experience one would have when using the product for the first time. The moral for the audience is that they too could enjoy this experience.

Figure 1.5

Nine values from which a persuasive story might emerge

EXERCISE 1.1 UNCOVERING PROJECT VALUES

Use the chart above to frame discussions for the scenario below.

You are interviewing with an airport’s board of directors in hopes of winning their upcoming signage and branding project. The city itself is small but rapidly growing, and rich in culture. |

List 2–3 bullet points conceptualizing how you might base your interview upon each of the 9 values. Write a paragraph discussing which one of the values you feel is most appropriate. Remember, more than one value would dilute your message. |

EXERCISE 1.2 UNCOVERING PROJECT VALUES IN YOUR WORK

Follow the steps from Exercise 1.1 for your own project.

PLOT

The story’s moral is made apparent through its plot. Plot is not only the story’s events, but what happens to the main character as they encounter conflict.45 Think of conflict as anything that provides the audience with a sense of urgency. This feeling of urgency can stem from the internal struggles of the main character as they battle against their demons or wrestle with their own misguided beliefs. Or the conflict can be due to an external force of evil. This foe can come in the form of another person, being, or tragic event.

Conflict is an important storytelling tool because when something is amiss, the audience will want to see how it can be resolved.

TYPES OF STORY CONFLICT

| main character, (protagonist) | vs. | force of evil (antagonist) |

| reality | vs. | the character’s reality |

| the character’s wants | vs. | what the character has |

| the character’s wants | vs. | what is expected of them |

| the character’s wants | vs. | the character’s fears |

In design storytelling, the sources of conflict will hinge on your goals and the values of your audience. These sources of conflict can range from a client battling for the hearts and minds of their customers, despite having few resources, to a designer grappling with the problems faced by homeless children. Typically, the best sources of conflict are interesting, relevant, and meaningful to your audience.

CONFLICT REVEAL

Your audience’s time and attention will likely be short in supply, so your story will need to pique their interest quickly. Author Lisa Cron suggested that storytellers tease their audiences with a “breadcrumb trail,” meaning that the storyteller should provide just enough information to keep the audience moving forward through the story.46 This is similar to progressive disclosure, which can be thought of as giving the audience just enough information, just when they need it. The goal is to get the audience anticipating the consequences of each event. That is to say, something is amiss, or out of balance, and if it does not get resolved, something bad might happen. This type of breadcrumb trail activates our dopamine neurons, keeping us immersed in the folds of the story.

EXERCISE 1.3 EXPLORING CONFLICT

Think back to your favorite book or movie.

Write a paragraph summarizing your answers to the following:

What was the conflict?

What made it interesting?

Is the conflict best characterized as a character’s internal struggle, or a battle against an outside foe?

STORY STRUCTURE

Once the conflict has been defined, consider how it will unfold within three different segments. These sections can seamlessly flow from one to the next, so their boundaries may remain unknown to the audience. But for the storyteller, each segment represents different working goals. We’ll call these segments, Launch, Load, and Landing.

Think of the Launch as when the story’s events are set into motion, either gradually or at breakneck speed. In either case, the conflict should be made apparent right from the beginning. Then, along the breadcrumb trail, the stakes are made known, and the characters are defined. The Launch is critical to not only gaining the attention of the audience but framing the story’s elements. Once the audience understands these introductory elements, they will be used to judge every subsequent event and how these events impact the main character.

Load can be characterized as adding any elements that are necessary to move the story forward. This can range from providing context, defining the contours of the conflict, or even offering potential solutions.

At Landing, the story comes to a halt. The conflict is resolved – with either positive or negative consequences for the main character. Since the moral plays a critical role in promoting the desired action, it should either be implicitly or explicitly visible at the story’s conclusion.

STORY SEGMENTS

| Goals | Description | |

| Launch | pique interest and establish: who what when where |

The introduction should include defining elements about whose story it is (i.e., who is the main character), what is happening, and what is at stake. |

| Load | provide context define conflict share information | This is where the action takes place. The audience is provided with more context and is offered potential solutions. |

| Landing | provide resolution that refers to the moral | The ending completes the main character’s journey, thus resolving the story. It is important for the ending to offer the moral. |

OTHER PLOT TYPES

One interesting thing about stories is how many different messaging strategies there are. Most stories aren’t epic novels, and not all will follow a linear trajectory. Some may employ foreshadowing and flashbacks to provide context and intrigue. Yet, designers rarely have the time or the need to leverage these devices in design presentations.

At the same time, stories can be very short and without a proper beginning, middle, and end. Stories can be told even from a single profound image. Many of us can identify with the heartbreak behind a photo of the World Trade Center site taken on September 12, 2001, or the joy of an athlete winning an Olympic medal. See Chapters 6–8 for tactics in visual storytelling. No matter what strategy is employed, the key is to consider the values of the story first, and then decide how to tell it.

CHARACTER

Many of us already know that the main character of the story is the protagonist and the antagonist is typically the bad guy – which of course does not have to be a guy, or even a person at all. However, the most enduring stories, and the ones that move an audience to action, often feature characters with whom they can identify.47 In fact, studies have suggested that if we can identify with a character, we are more likely to give to their cause.48 This is why nonprofits often highlight the plight of a specific individual, even when their group may be helping millions of worthy people. Audiences are often more swayed by a personal story than the magnitude of the cause. This is because they can develop a relationship with a character and, by extension, the character’s goals and ideals. If a likable character’s life revolves around a certain value system, we too may come to value it. We can share their hope as they reach for their highest potential, and feel their pain as they face challenges along the way.

Our capacity to judge characters makes it easier for us identify with them. Social intelligence theories suggest that we do this by interpreting the identity, status, and intentions of others.49 This means that character development can be complicated. In fact, there are entire volumes dedicated to the craft. However, it is unlikely that a design story will need to provide extensive character elaboration and Sachs provides a brief, but useful, character development framework he calls “Freaks, Cheats, and Familiars.”50 Under his premise, we define Freaks as new and interesting, while Familiars remind us of ourselves or someone we know. Finally, depending on their circumstances, we either hope for or root against Cheats who have opted to challenge the status quo.

SACH’S CHARACTER TYPES

| Freaks are compelling. |

| Freaks are interesting because we consider them as different or new. |

| Familiars convey qualities that we all understand. |

| We understand familiars because we already know them as a reflection of ourselves or others we know. |

| Cheats are those that break the rules. |

| We either root for cheats to succeed because they are battling an injustice or difficult situation, or we hope that they will be punished for their shameful actions. |

While characters make a story interesting, in persuasive design storytelling, there will be added focus on how to orchestrate your story for maximum emphasis on either your point of view, the merits of your design, or your potential for a position or project. We will explore these topics in Chapter 3.

EVERYONE HAS A STORY

Each of us has a unique vantage point on the world.

This gives each of us a different story to tell.

Consider your personal story …

STORY STARTERS

| People |

| Think of people you have known & their experiences. What are their stories? How did they impact your life? |

| Places and Events |

| Recall places you have spent time. What do you recollect about them? How did they make you feel? |

| Things |

| Think of objects that hold value. Why are they significant? How did they become significant? |

STORYTELLING IN PRACTICE

How do you tell a client that their staff doesn’t like to work there?

As an experienced designer, most clients value my opinion and recommendations, but coupled with the words and photographs from their own employees, the truth can become undeniable and design recommendations can become even more powerful. Let me explain … I was working with a prominent “research think tank” in Washington, D.C., whose business, workforce demographics, and technology were rapidly changing, but senior leadership was in denial. Their office space and desktop computers was not in sync with their mostly Millennial workforce.

Our design team took a research-based project approach with their employees at the heart of the research. We gathered information through employee surveys, group focus groups, one-on-one interviews, observation, and camera journaling. Camera journaling is essentially an interview through photos to answer a series of questions. It gave us the richest information on what staff valued, what they liked and didn’t, and where they feel the most productive. We discovered a huge disconnect between the leadership vision and how their staff were working and the technology that they needed to get their work done more effectively. We knew we needed a compelling way to deliver the message. For our presentation, we covered all four walls of their corporate boardroom with floor-to-ceiling banners containing the photo journaling of their employees. As the leadership entered the room, they couldn’t help but be captivated by the photos and candid comments by their employees. By the time we presented our observations and recommendations, they were sold!

SUMMARY

Humans are drawn to stories, and they have long served as an invaluable means of communication. Research even illustrates the influence of stories and how they set in motion a series of reactions within the brain. These reactions can alter the way we behave and how we interact with others, and can even change our beliefs.

We like stories because they can help us build and refine our social connections. They allow us to organize and understand information through causal reasoning and by aligning a story’s events to our own experience. Finally, stories serve as a guide in determining right from wrong, and since we can live vicariously through a character, we can learn from their missteps without facing the same consequences.

To influence their audience’s beliefs, a design storyteller should first consider the values that they are aiming to represent. The morals of the story give life to these values. These morals are tested through conflict, as the character struggles for resolution. To pique interest, the conflict should be apparent right from the beginning of the story. However, in order for the audience to care whether or not the character even resolves the conflict, they need to identify with them on some level.

While storytelling can at first feel uncomfortable, stories can provide an opportunity to not only connect with project stakeholders but to actually reach them and prompt them toward a more desirable course of action.

The following chapters will explore the contours of design storytelling by giving definition to your audience and goals, and then identifying and refining the communication tactics that will be used to share your own design story.

FOR CONSIDERATION

What if we’re scared of storytelling?

While we are beginning to understand the virtues of storytelling, in professional settings, storytelling can feel unnatural, and for a good reason. Often a story requires its tellers to share their vulnerabilities, forcing them to be transparent in order to be authentic. Storytellers often need to convey emotions, which can be embarrassing. Moreover, some stories recall a personal experience that may be difficult to share.

Stories can also be sabotaged by calling on a misplaced message or even with our own delivery. With proper planning (and some practice), however, the art of storytelling can be a powerful asset in any designer’s toolkit.

TERMS

| affective primer | conflict | progressive disclosure |

| antagonist | Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs | protagonist |

| causal reasoning |

APPLICATION 1.0

Storyteller Kendall Haven suggested that effective stories provide an audience with: context, relevance, engagement, understanding, empathy, and meaning, as well as enhance their memory and recall.51 The aim of this book is to help you to provide your audiences with these insights by conceptualizing a design for a story for an upcoming project. To introduce this process, first think back to a previous project and consider the following questions.

1 Refer to Figure 1.5. Which value (Justice, Wholeness, Perfection, Richness, Simplicity, Beauty, Truth, Uniqueness, & Playfulness) most closely aligns to that project?

2 Focusing on this value, what would you consider the moral of the story to be?

3 What are sources of potential conflict that would best test this moral?

4 Answer the following:

Who is the protagonist?

Would the audience consider them a freak, familiar, or a cheat?

How do these characterizations influence the story?

Are there any other necessary characters that contribute to the story?

5 Using your answers, conceptualize the following aspects of your story.

| Launch Introduction | Load Middle | Landing Ending | ||

| pique interest establish: who what when where |

provide context define conflict share information | provide resolution refer to the moral |