Tools of the Trade, and More

There are a few more things that it is useful to know, as a graphic designer, when taking your job to a print shop.

Film

While most of us will end up using a CTP workflow, some print shops still create film from the digital file. Plates are then made from the film. In this case, the printer owns the film.

Film is technically a tool of the trade, and actually belongs to the printer unless it is specified on the invoice. Then, and only then, is it yours.

If you tell the printers when you call for an estimate that you want to take the film away with you at the end, they might feel inclined to charge you something extra for doing so. On the other hand, if you do not ask for the film until they call you to say that your job is ready to pick up, you might end up paying for the film twice—once for the set they used to print the job (which belongs to them), and once for the set that you want to take away and keep. In fact, there is probably only one set—but you get to pay for it twice.

A way around this, sometimes, is to get a quote for the job, and only after receiving it tell the printer that you want the film to be specified on the invoice. They will be less inclined at that point to tell you that there will an additional charge… so, this method is a bit sneaky.

Incidentally, while it is sometimes worth making sure that the film is yours to walk away with, this is almost never the case with plates. For one thing, you would have to take them to another shop with exactly the same press. Also, it is easy to damage plates and harder to transport them once they have been on a press, as the edges are crimped from the machine grippers. Because of their sensitivity and odd shape, it is almost certain that by the time you have gone to all the trouble to get them on another press, you will find there is a tiny scratch somewhere that nobody noticed before. And scratches, of course, will show up on the print. If they are in a blank area, they can be dealt with. If they are across a halftone, on the other hand, the plate is scrap and it has all been a waste of time for everybody—time that somebody will want to charge you for.

Over- and underruns

Another unpleasant surprise awaits those who need a very specific number of copies of a job printed: if, for example, you have ordered 1,000 copies of a program for the 1,000 people attending an event, but the printers hand over only 900.

Despite what you might think, they are probably under no legal obligation to put the job back on the press. Of course, they will make an adjustment to your bill—but that is also likely to be a shock. It will not be 10% less than the estimate, even though they have come up 10% short on delivery. That is because the job is divided into two areas: Set-up and production. Set-up costs are things like film, plates, and setting up machinery such as folders. All this costs the same whether they run one copy or 100,000. Production costs are things like paper, press time, folding time, etc. Obviously, these will vary according to the quantity involved. In this case, you will not get any reduction on the set-up side of things, but you would get a 10% reduction on the production costs.

However, you cannot ask the printers to put your job back on the press and print the other 100 copies. Trade conventions in the UK and the US allow as much as a 10% over- or underrun, and the only way to avoid it is to a) read the small print if you are signing a contract, or b) make an agreement beforehand with the printers, in writing, that they supply not less than a specific quantity. In the US, the percentage actually varies from state to state, but tends to be lower than in the UK—for example, in California, it is typically 3%. Of course, in order to guarantee delivery of a fixed number of copies, the printers will probably feel the need to order slightly more paper than they otherwise would, which means they also have to allow for slightly more press time, folding time, binding time, etc. So under these circumstances you should expect to pay a little more.

Cutter draw

There is a nasty little phenomenon that you should know about regarding the trimming of your job, because it can affect the quality of the final result even if everything goes well on the press.

It particularly affects crossovers. These are images that cross over the binding in order to appear on adjacent left- and right-hand pages in a double-page spread. This means each half is printed on a different press sheet. The complete crossover image appears only when the sheets are collated, folded, and trimmed properly.

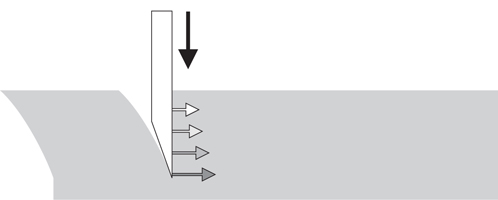

If cutting (fig. 12.22) is being done prior to the folding (which is most often the case), there is a good chance that you will get some degree of “cutter draw” in the result (fig. 12.23). This is when the blade of the cutter bends as it cuts through a stack of paper—and the thicker the stack, the greater the effect. At the top of the stack, everything is cut along a straight line. The closer you get to the bottom of the stack, the more the blade has curved and the less accurate the registration will be on all the subsequent operations for those sheets. That can mean that your crossover does not line up properly across the spine.

12.23 Seen from the side: The shape of the cutting edge forces the blade into the stack.

Seen from above: As the blade is anchored at both ends, the result of cutter draw is a curved cut.

In order to avoid this, talk to the printers beforehand and make them aware of your concerns. Ask that the bindery staff be told to cut the job in “small lifts,” i.e. a thinner stack of paper as opposed to a thicker one. Again, this will slow things down, so you will be paying a bit more for the job. But remember that old saying: “You can have it quick, cheap, or good. Pick any two.” Printing really is like that.

Sharpening the pencil

Over time, even a really good printer will become slightly complacent about having you as a client, and while in the early days they would trim their quotes wherever possible to give you the most attractive price, they will do so less and less as time goes by. I know this to be a fact, having once been the estimator in a good print shop. So, to keep the price down, you might try the following. Every few jobs, mention that, alas, the boss has asked you to bid this one out to two or three other print shops, so would they please keep their pencils sharp when running the numbers as you would prefer to see them get the work.

A final word about printers: when you find some good ones, cherish them. Helpful printers will benefit you and every job you send to them, allowing your clients to recommend you to all their friends with a clear conscience. That is the best kind of publicity you can ever get. I have worked with good printers, and bad, and there is an ocean of difference between them. Most printers will do their absolute best to give you the quality you want, not just because they want you to come back again and again, but because they are decent people who take pride in the job they do.

And a final note about everything else: if this book has helped you, then please use it to help someone else. And I do not mean you have to pass it along to a competitor for free. Just do something for somebody today, and maybe again tomorrow, with this book in mind. Only then will writing it have been worthwhile.