Other Printing Methods

As I have said, this book is primarily concerned with sheet-fed offset litho, but graphic designers may also be asked to work with one of the other industrial printing mediums. Here is a brief description of the four most common of them.

Web offset litho

Web offset litho relies on the same kind of process used by sheet-fed offset litho with one notable difference: instead of printing sheets, it prints a continuous roll, or web. It is therefore capable of incredible speed and commonly prints both sides of the sheet in the same pass, a process called perfecting.

Web machines can be frightening not only in terms of size and noise level—some are as tall as a two- or three-story building and sound like an express train—but also in terms of how fast the hapless designer who is proofing the job on-press has to make decisions.

As the web leaves the last ink unit, it is folded and then cut into sheets as part of the “in-line” process, and this, of course, means that the ink on the paper must be absolutely dry. Infrared or even propane dryers are commonly mounted between each ink unit to ensure that all the colors have set before the folding begins. An exception to this is newsprint, which uses cold-set inks. These are formulated to dry very quickly on absorbent paper stocks.

Because of the speed of production, web inks are thinner than those used for sheet-fed work. Dot gain levels (see Chapter 4) are therefore different—roughly double those of sheet-fed. They also sometimes vary from press to press even within the same shop, so be sure to check with the printer before finally calibrating any images.

Flexography

This method is mainly used for packaging. The plates, which are made of a rubber compound, look as if they have been etched as the surface stands out from the background. In fact, flexography plates are usually made in a mold. Because of their flexibility and three-dimensional surface the plates tend to “squish” somewhat under the pressure of transferring the ink to the page. This means that small dots can get considerably bigger, and dot gain levels can therefore be serious. Registration tends to be rather looser than with offset litho, but a plus is the ability to print onto non-absorbent surfaces such as plastic and metal. If you are going to print using this method, talk to your printer about the kind of images you want to include in the job before you put everything together. Definitely ask about dot gain, screen density, and registration tolerances, which can vary considerably from shop to shop. Although small type and fine screens are normally to be avoided when using flexography, there are specialist printers in the field who can produce things like 4pt type and four-color 133-line screens beautifully.

Screenprinting

Imagine a mesh stretched across a wooden frame that has then been placed face down on a table. That is the idea of a “screen” in screenprinting. Of course, the frame is much more likely to be made of metal, and the screen is much more likely to be a very fine polyester or metal mesh, but the basic idea is the same.

Ink is poured onto the mesh along one of the edges of the frame. The screen, which is a porous membrane, carries on it the image background, which acts as a non-porous stencil.

As the ink is pulled across the membrane by a rubber-edged squeegee, ink is forced through the porous areas—i.e. the image—and onto the page beneath. Then the frame is lifted, leaving the page behind. It is removed, a new one is put into its place, the frame comes down again, and the ink is squeegeed back across it.

Of course, the “page” used in screenprinting is quite often something like a T-shirt, but this method is also used for physically large pages on very small runs—for instance, store signs. The appropriate images can be printed, one frame at a time, across a 16-foot (5-meter) sheet of the material from which the sign is being made.

The methods by which the image is created on the screen vary enormously. At one end of the scale, the image can be painted onto the screen by hand. At the other, a photosensitive material is bonded to the mesh onto which the image is generated, in much the same way that offset-litho plates are made, i.e. from an exposure through a sheet of film that carries the image, or even by direct exposure to laser.

Screenprinting is not a method that lends itself to very fine detail, and sometimes the mesh of the screen can add a new twist to trying to avoid moiré patterns in four-color work. But obviously there are areas into which screenprinters can go that other printing methods cannot reach. Screenprinting is not always a manual operation. There are also fully automated systems in use that can provide much faster and more consistent results.

Gravure

Gravure (or Rotogravure) is the printing method that makes banknotes so hard to forge. It uses either a diamond-etched copper plate or a laser-etched polymer resin plate; either way, the printing process is the same.

Gravure plates are very thick compared to those of sheet-fed and web offset. Instead of the ink adhering to the portions of the plate that are left as a raised surface, gravure plates rely on using a much thinner ink that fills the “cells” etched into it. The deeper the cell, the more ink can be held—and the darker the corresponding dot on the paper. Excess ink is continually wiped off the raised surfaces of the revolving plate by a steel blade.

Because the ink is thinner, it spreads when it hits the page. This means that the printed result appears to be a continuous tone. This makes gravure the highest-quality option for image reproduction, but conversely a lower-quality option for type, which will also be made up of the same kind of cells as the image.

Originally, gravure cells were all of equal size but varying depths, but it is now possible to use cells of varying size as well. Gravure platemaking is extremely expensive, and as it is also a web printing process it is much more involved (and therefore more expensive) to set up and run than a simple sheet-fed press. As a result, gravure is usually suited only to extremely long press runs.

An environmental note

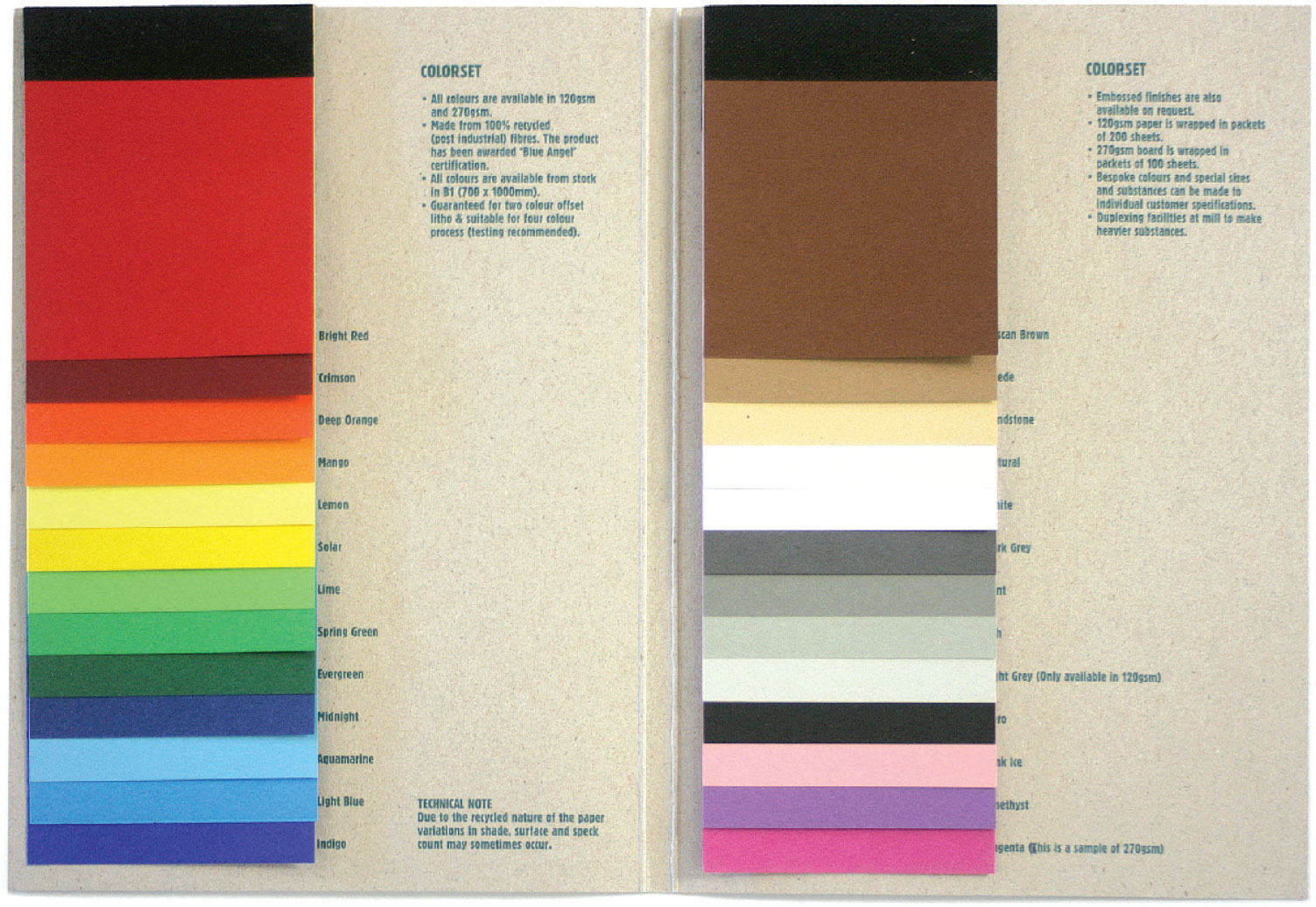

Whichever method you choose, printing is a messy business. It can also be highly toxic. Film chemicals are nasty, as are some used for developing plates, while inks can contain all sorts of heavy metals, and the solvents used to remove them afterward are usually varying grades of jet aircraft fuel. So, if possible, encourage your printer to use a more environmentally friendly system. Both water-developing plates and soy-based inks are available, and a computer-to-plate system completely avoids the use of film. Also, try to use recycled paper whenever possible: a single weekend edition of the New York Times requires the wood from more than fifty acres of forest (fig. 1.11).

Do not assume that the kind of paper you want is not made in a recycled stock—the range available today is huge. Just call your printers and talk to them.

1.11 A swatch of recycled paper samples. Recycled stock is available almost everywhere.

A color separation shown in cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, each screened to the appropriate angle to ensure successful printing.