Film Technology

Commercial offset lithography, the printing method with which this book is mostly involved, relies on an image that has been photographically generated (an analog process, i.e. a physical and therefore a “lossy” transfer) or electrostatically generated (digital, i.e. “lossless” transfer) on a plate. Plates are typically thin sheets of aluminum coated with a photoreactive emulsion. When an exposed plate is developed, the image areas tend to attract oil-based inks, whereas the background areas tend to attract water. By keeping a delicate balance between the ink and the water—which is provided by a unit called the damper system—the right stuff sticks to the right areas and what you end up with is something capable of generating a printed image. Although the materials may vary—for example, you can even get paper plates—the basic idea has remained the same. (There is a more detailed discussion of the offset litho process on page 20.)

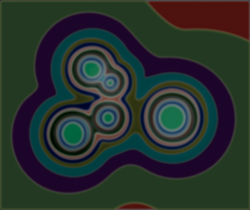

For an example of how litho film generates a plate, let us assume that we have assembled the art for an entire printed image and taken an accurate photograph of it. This photograph might have been film generated by an imagesetter that got its information from a disk, or it might have been film generated by the paste-up, darkroom, and “film stripping” (highly skilled assembly of film from different sources to make up a complete job) departments in a film-based print shop. In order to make a plate, we have to lay the film, emulsion side down, onto the plate (which is emulsion side up), and expose them both to light in order to transfer the image from one to the other. This is done in a glass-topped vacuum frame that sucks all the air from between the film and plate prior to the exposure to ensure a crisp transfer of image. Specks of dust, or other foreign bodies trapped inside, create intense pinpoints of uneven pressure that show up on the glass as Newton’s Rings (fig. 1.7). These are dark, rainbow-colored concentric circles that show where subsequent problems might occur. Obviously enough, if a foreign object gets caught between the film and the plate in the middle of a halftone, there will be a distortion of the resulting plate image at that point. So the operator scans the whole plate area carefully for any sign of Newton’s Rings. If they show up in a potentially dangerous area, the operator turns off the vacuum, waits for the pressure to equalize, then lifts the lid to remove the speck. Sometimes it takes a while to make a good plate. When it finally looks clean, the operator can start the exposure, which is usually done with ultraviolet light. This cooks the surface emulsion and hardens it, so that when the plate is developed, the image is left behind while the background is washed away.

1.7 Newton’s Rings.

There are some geographical differences in the process, depending on where in the world you happen to be. In the US, negative-working film and plates are much more common, whereas in Europe and Asia almost everyone uses positiveworking materials instead. Either way, it does not make too much difference. Negative plates can (usually) be protected for future use with a thin coating of gum arabic, whereas the image on positive plates will (usually) continue to be affected by light and will not be of much use to anyone shortly after the protective layer of ink has been washed off. Negative plates will (usually) need to be replaced part of the way through very long runs, whereas positive plates can (usually) keep on going well beyond 100,000 impressions. There are, of course, exceptions to these generalizations, but to detail the differences between the most common materials in use worldwide would require a great deal of space, and as it is information that is mostly useful only to a printer trying to match the appropriate materials to a specific job, it is information that is not of much use to a designer. The suitability of that match, however, can be part of the reason why the quote from one print shop might be very different to the quote from another. A good price depends on the availability of the appropriate press and the most cost-effective materials, given the size of the printed piece and the number of copies required.

Film and plate processors are now to be found everywhere, and their use avoids most of the difficulties inherent in manual plate and film developing. Chemicals circulate so that they are maintained at a constant strength, the temperature is held at the optimum level, and working materials are pulled through on rollers ensuring that they are only kept in the various solutions—traditionally a sequence of developer, fixative, and wash—for the correct length of time. Plate processors especially are to be found in shops running CTP and direct imaging (DI) operations, which do not bother with film at all.

1.8 An imagesetter producing an offset-litho plate directly from digital information.

1.9 A digital press, which uses neither plates nor film.