Jude Brereton, et al.

224

100

90

80

70

60

%

50

2012 2013 2014 2015

Year

2016 2017 2018 2019

He She They Unavailable Trend line for He

Figure 14.4 Gender Representation of Presenters at AES Conferences, 2012–2019

Source: Data from Young et al. 2018 and https://tibbakoi.github.io/aesgender/.

Of the 57 respondents, 39 were involved in instrumental music lessons,

three in ensembles, 13 in school music lessons (both GCSE and A Level),

but only one in studying Music Technology (A Level). Nine respondents

reported some involvement in additional music technology activities, such

as helping with sound or lights for school productions or mixing perfor-

mance soundtracks.

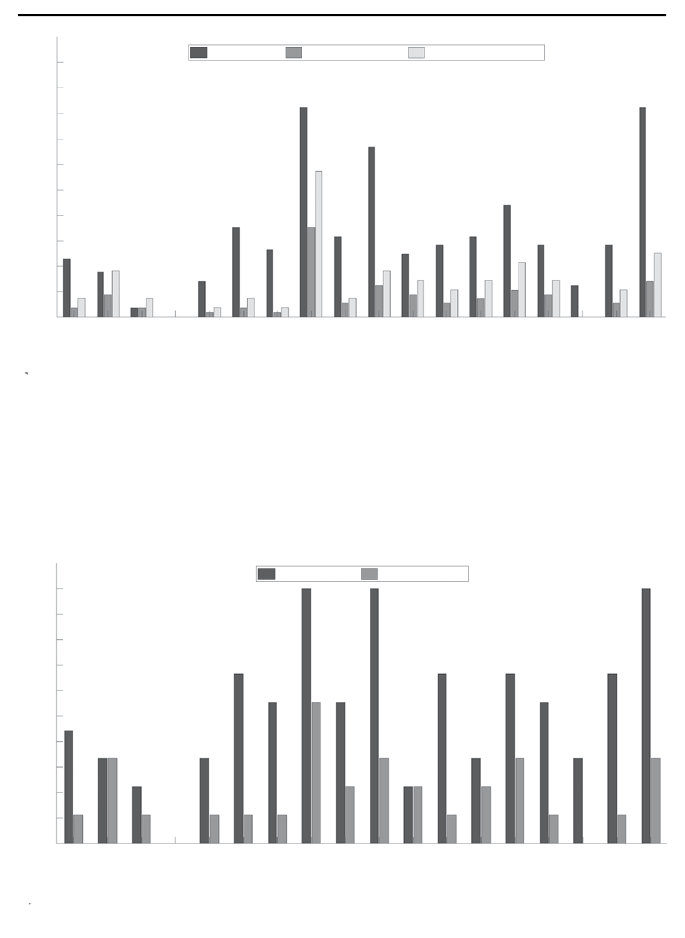

Eighteen job roles were listed in the survey, covering a variety of aspects

within audio technology, music production, and the audio industries (seen

in Figure 14.5). The respondents had heard of the majority of roles (most

dark grey in Figure 14.5), with “producer” (82%), “composer” (82%), and

“software developer” (67%) the most recognized.

However, the numbers of respondents potentially interested in taking

up each job role is substantially lower (middle grey in Figure 14.5). Only

49%, despite being involved in music or music technology, said they were

maybe or definitely interested in a job in the music industry (indeed, only

4/57 said “yes definitely”). Results for these 28 respondents have been

extracted and plotted in the lightest grey in Figure 14.5: “Adjusted Inter-

est”. In alignment with the roles most heard of, producer and composer

have the largest percentages: 57% and 25%, respectively.

It seems that very few respondents were interested in any of the roles

associated more with engineering (only 7% were interested in “mixing

engineer” or “research engineer”, and only 4% “acoustic engineer”).

All nine respondents who had some form of music technology experience

(whether through formalized education or additional activities) reported

“yes” or “maybe” interested in a job in the music industry/music produc-

tion. These respondents appear to have heard of more of the job roles than

the general respondents; however, the number of respondents interested in

each role is still low, with the exception of “producer” (see Figure 14.6).

225

Addressing Gender Equality in Music Production

100

Heard of Interested in Adjusted Interest

90

80

70

60

%

50

40

30

20

10

0

Mixing engineer

Music curator

Restoration engineer

Foley artist

Boom operator

Audio programmer

Acoustic engineer

Producer

Research engineer

Software developer

VR/AR developer

Broadcast engineer

Edit assistant

Audio designer

Recording engineer

Quality assurance tester

Audiologist

Composer

Figure 14.5 Percentage of Respondents Who Had Heard of the Listed Job

Roles and Who Were Interested in Each Role (calculated as the fraction of total

respondents). Adjusted interest is those respondents who said “yes” or “maybe”

to interest in a job in the music industry (calculated out of 28).

100

Heard of Interested in

90

80

70

60

%

50

40

30

20

10

0

Mixing engineer

Music curator

Restoration engineer

Foley artist

Boom operator

Audio programmer

Acoustic engineer

Producer

Research engineer

Software developer

VR/AR developer

Broadcast engineer

Edit assistant

Audio designer

Recording engineer

Quality assurance tester

Audiologist

Composer

Figure 14.6 Percentage of Respondents With Some Music Technology Experience

(nine respondents) Who Had Heard of the Listed Job Roles and Who Were

Interested in Each Role.

“Composer” does not feature highly in this subset of respondents, where it

is one of the more popular in the general set. This is to be expected, as the

data can be interpreted as it is likely that the other respondents are studying

music rather than music technology. It seems that, for the female students

we surveyed, having some experience of music technology at school raises

226

Jude Brereton, et al.

awareness of the range of job roles available under the wide umbrella, but

does not necessarily translate into an active desire to pursue these roles.

Negative perceptions of the industry may be driving this trend.

Attempts to gather and publicize data on gender in the audio and

music industry are relatively recent (for a good example, see Women In

Music

2

), and data collected invariably re-emphasizes the small propor-

tions of women/non-binary participants in music technology and audio-

related subjects at school, college, and in tertiary education – there are few

surprises.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHANGE

As data attests, audio engineering, music production, and music technol-

ogy have traditionally been male dominated, a position which unfortu-

nately seems to be resistant to speedy change. In this section we look

briefly at some of the current interventions which seek to address gen-

der balance in music production, note some of the successful initiatives

and bank of knowledge that has been drawn together on gender equality

in STEM disciplines, and discuss the opportunities for change unique to

music production which can be exploited.

Interdisciplinary Nature of Music Production

Music production and music technology are inherently interdisciplinary

pursuits, with methods, approaches, and knowledge shared among the sep-

arate disciplines of music, art, engineering, creativity, performance, analy-

sis, and technology. It might, therefore, seem odd that music production

has become so male-dominated when the related fields are often praised

and noted for their truly interdisciplinary nature.

This nature of music technology and music production is, potentially, a

real draw for those looking to work across traditional arts/science disciplin-

ary divides. A review in 2007 identified a large number of sub-disciplines

involved in sound and music computing including music, music composi-

tion, music performance, science and technology, physics, maths, psychol-

ogy, and engineering (Bernardini and de Poli 2007; Serra et al. 2007).

However, as Boehm (2007) and Boehm et al. (2018) argue, Music Tech-

nology moving from interdisciplinary to truly transdisciplinary and, as

such, transforming into a single discipline in itself has not materialized.

Reasons for this are many and related to external motivations and pres-

sures on both school and tertiary-level education. Since 2012, STEM (sci-

ence technology engineering and maths) subjects have been better funded

by government. This has led some institutions to adapt Music Technology

programs to increase their focus on the science/technology element of the

discipline, potentially as a means to attract greater numbers of students,

exploiting the perception that employment prospects are increased for

those studying STEM rather than arts-based subjects.

What is more, the traditional idea of a music producer as closely aligned

with that of an engineer is very often one that prevails, despite music

227 Addressing Gender Equality in Music Production

production encompassing a huge variety of skills and not just relying on

the mastery of technology.

There is a danger that the interdisciplinary nature of music production

means that those in the industry and education are not fully involved in

initiatives to address gender equality that are led by and housed under

single disciplines of music and engineering, such as the PRS Keychange

Manifesto (PRS Foundation 2018) and the Engineering UK campaign on

diversity (This is Engineering 2018).

Campaigns are, however, becoming more popular, especially as they

learn to exploit the potential of social media, and are playing an important

role in setting the scene for significant change by raising awareness of

gender issues.

Increased Awareness of Gender Issues

The need for work to address gender equality in many areas of life seems

to be receiving renewed interest in the media, with blockbuster films

highlighting the role of women in space science, the #MeToo movement,

issues around the gender pay gap highlighted in the press, and high-profile

public figures giving support.

The results of a non-diverse engineering sector on our modern world are

also increasingly being discussed. Ely (2015) presents a series of exam-

ples where design does not meet the diverse needs of end users as a result

of the non-diverse workforce: the design and testing of car seats, seat belts,

power tools, and medical research have all historically failed to include

women.

For the audio industry, the gender data gap is also an issue since much

of the seminal established literature in areas such as audio perception has

been based on male participants. There is now an increased awareness that

participants in perceptual studies should be gender balanced and results

reported by gender where possible. This is especially important in particu-

lar areas, for example, in research on spatial sound perception and where

researchers are trying to tailor sound reproduction based on the size and

shape of the listener’s head.

An increase in the participation in research studies by female stu-

dents and researchers will help to raise awareness of the interdisciplinary

research being undertaken in audio and might help to address the gender

imbalance in the field in the future.

Many departments in higher education institutions in the UK have

engaged with the Athena SWAN charter, which promotes interventions

to tackle gender inequality in academia. It originated within science, but

has since expanded to all academic disciplines. As such, there is now

perhaps a wider understanding of some of the social and work-based bar-

riers that those in under-represented groups face in any arena, including

imposter syndrome, stereotype threat, unconscious (and conscious) bias,

the leaky pipeline, in-group socialization, nepotism, homosociative hab-

its, the glass ceiling, lack of role models, prevalent gender schemas, and

sexism (Valian 1999).

228

Jude Brereton, et al.

The music industry has similar problems to those found in academia; a

recent survey of women in the US music industry (Prior et al. 2019) found

that the majority had experienced gender bias, and that nearly half felt

that they were given less recognition than their male peers and that their

careers had been held back because of gender. Women of color in particu-

lar felt less well supported in the workplace.

Much of the academic literature in this area seeks to address the prob-

lems of women leaving a discipline (known as the “leaky pipeline” (Ceci

et al. 2009)), often in disciplines with equal numbers of male and female

undergraduate students (such as chemistry), or with greater numbers of

female students at the undergraduate level (such as biology; see, for exam-

ple, Burrelli 2008). But music production and music technology attract

low numbers of female students to start with, and although efforts to retain

women within the industry are valid, we need first to better understand

why women are not involved in the discipline throughout school, univer-

sity, and into work.

Fixing the Industry

Although much effort has been expended to encourage female students to

consider STEM careers, and within that music technology more specifi-

cally, all of these efforts will be wasted if we don’t make a concerted effort

to address the culture of the industry itself.

We must address the justified perception of the music industry as heav-

ily male-dominated and toxic. As we noted earlier, although women are

now equally represented within the music industry workforce as a whole

(Prior et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2019), they are still under-represented, over-

looked, undervalued, overcriticized, excluded, and sexualized as perform-

ers, composers, and producers. They face entrenched sexism, a lack of role

models, and multiple barriers to entry that means that any female musician

or producer must fight significantly harder than her male musical peers for

recognition (Prior et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2019).

A clear and very common example of this hostile environment can be

seen in the online comments made on one video which is part of a series

of over 500 video interviews with music producers in their studios. Here,

Catherine Marks, winner of the Music Producers Guild 2016 “Break-

through Producer of the Year Award” and 2018 “UK Producer of the Year

Award”, talks about her approach to recording and production. One of

the comments posted reads: “Hot and an engineer toooo!!!!” (We looked

at many of the interviews with producers and could not find a similar

comment directed towards a male producer.) Female music producers and

women working in the audio industry also face subtle (hidden) as well as

overt (open) discrimination and gender bias; this is the case too in other

areas where a discipline is male dominated (Heilman and Welle 2005;

Jones et al. 2016).

There has been plenty of recent research on women in science and

academia over the last 20 years, as well as organizations working in this

space to champion gender equality in science and engineering, such as the

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.