After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Aristotle once said, "Wealth does not lie in ownership but in the use of things"! Clearly, many U.S. companies have decided that Aristotle is right, as they have become heavily involved in leasing assets rather than owning them. For example, according to the Equipment Leasing Association (ELA), the global equipment-leasing market is a $600–$700 billion business, with the U.S. accounting for about one-third of the global market. The ELA estimates that of the $850 billion in total fixed investment expected from domestic businesses in 2006, $229 billion (27 percent) will be financed through leasing. Remember that these statistics are just for equipment leasing; add in real estate leasing, which is probably larger, and we are talking about a very large and growing business, one that is at least in part driven by the accounting.

What types of assets are being leased? As the opening story indicated, any type of equipment can be leased, such as railcars, helicopters, bulldozers, barges, CT scanners, computers, and so on.

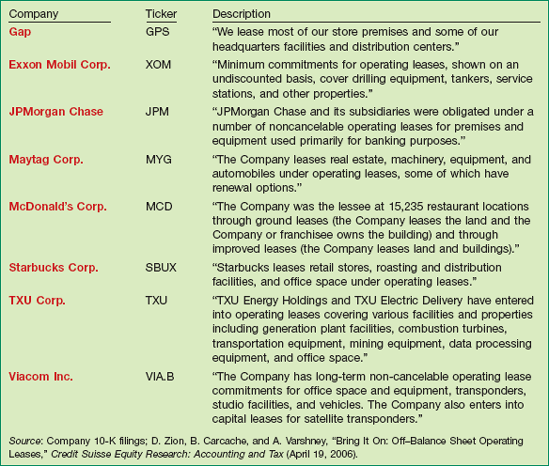

Illustration 21-1 summarizes, in their own words, what several major companies are leasing.

The largest group of leased equipment involves information technology equipment, followed by assets in the transportation area (trucks, aircraft, rail), and then construction and agriculture.

A lease is a contractual agreement between a lessor and a lessee. This arrangement gives the lessee the right to use specific property, owned by the lessor, for a specified period of time. In return for the use of the property, the lessee makes rental payments over the lease term to the lessor.

Who are the lessors that own this property? They generally fall into one of three categories:

Banks are the largest players in the leasing business. They have low-cost funds, which give them the advantage of being able to purchase assets at less cost than their competitors. Banks also have been more aggressive in the leasing markets. They have decided that there is money to be made in leasing, and as a result they have expanded their product lines in this area. Finally, leasing transactions are now more standardized, which gives banks an advantage because they do not have to be as innovative in structuring lease arrangements. Thus banks like Wells Fargo, Chase, Citigroup, and PNC have substantial leasing subsidiaries.

Captive leasing companies are subsidiaries whose primary business is to perform leasing operations for the parent company. Companies like Caterpillar Financial Services Corp. (for Caterpillar), Chrysler Financial (for Daimler-Chrysler), and IBM Global Financing (for IBM) facilitate the sale of products to consumers. For example, suppose that Sterling Construction Co. wants to acquire a number of earthmovers from Caterpillar. In this case, Caterpillar Financial Services Corp. will offer to structure the transaction as a lease rather than as a purchase. Thus, Caterpillar Financial provides the financing rather than an outside financial institution.

Captive leasing companies have the point-of-sale advantage in finding leasing customers. That is, as soon as Caterpillar receives a possible order, its leasing subsidiary can quickly develop a lease-financing arrangement. Furthermore, the captive lessor has product knowledge that gives it an advantage when financing the parent's product.

The current trend is for captives to focus primarily on their companies' products rather than do general lease financing. For example, Boeing Capital and UPS Capital are two captives that have left the general finance business to focus exclusively on their parent companies' products.

Independents are the final category of lessors. Independents have not done well over the last few years. Their market share has dropped fairly dramatically as banks and captive leasing companies have become more aggressive in the lease-financing area. Independents do not have point-of-sale access, nor do they have a low cost of funds advantage. What they are often good at is developing innovative contracts for lessees. In addition, they are starting to act as captive finance companies for some companies that do not have a leasing subsidiary.

According to recent data at www.ficinc.com on new business volume by lessor type, banks hold about 44 percent of the market, followed by independents at 30 percent. Captives had the remaining 26 percent of new business. Data on changes in market share show that both banks and captives have increased business at the expense of the independents. That is, banks' and captives' market shares had grown by 58 percent and 36 percent respectively, while the independents' market share declined by 44 percent.

The growth in leasing indicates that it often has some genuine advantages over owning property, such as:

100% Financing at Fixed Rates. Leases are often signed without requiring any money down from the lessee. This helps the lessee conserve scarce cash—an especially desirable feature for new and developing companies. In addition, lease payments often remain fixed, which protects the lessee against inflation and increases in the cost of money. The following comment explains why companies choose a lease instead of a conventional loan: "Our local bank finally came up to 80 percent of the purchase price but wouldn't go any higher, and they wanted a floating interest rate. We just couldn't afford the down payment, and we needed to lock in a final payment rate we knew we could live with."

Protection Against Obsolescence. Leasing equipment reduces risk of obsolescence to the lessee, and in many cases passes the risk of residual value to the lessor. For example, Merck (a pharmaceutical maker) leases computers. Under the lease agreement, Merck may turn in an old computer for a new model at any time, canceling the old lease and writing a new one. The lessor adds the cost of the new lease to the balance due on the old lease, less the old computer's trade-in value. As one treasurer remarked, "Our instinct is to purchase." But if a new computer is likely to come along in a short time, "then leasing is just a heck of a lot more convenient than purchasing." Naturally, the lessor also protects itself by requiring the lessee to pay higher rental payments or provide additional payments if the lessee does not maintain the asset.

Flexibility. Lease agreements may contain less restrictive provisions than other debt agreements. Innovative lessors can tailor a lease agreement to the lessee's special needs. For instance, the duration of the lease—the lease term—may be anything from a short period of time to the entire expected economic life of the asset. The rental payments may be level from year to year, or they may increase or decrease in amount. The payment amount may be predetermined or may vary with sales, the prime interest rate, the Consumer Price Index, or some other factor. In most cases the rent is set to enable the lessor to recover the cost of the asset plus a fair return over the life of the lease.

Less Costly Financing. Some companies find leasing cheaper than other forms of financing. For example, start-up companies in depressed industries or companies in low tax brackets may lease to claim tax benefits that they might otherwise lose. Depreciation deductions offer no benefit to companies that have little if any taxable income. Through leasing, the leasing companies or financial institutions use these tax benefits. They can then pass some of these tax benefits back to the user of the asset in the form of lower rental payments.

Tax Advantages. In some cases, companies can "have their cake and eat it too" with tax advantages that leases offer. That is, for financial reporting purposes companies do not report an asset or a liability for the lease arrangement. For tax purposes, however, companies can capitalize and depreciate the leased asset. As a result, a company takes deductions earlier rather than later and also reduces its taxes. A common vehicle for this type of transaction is a "synthetic lease" arrangement, such as that described in the opening story for Krispy Kreme.

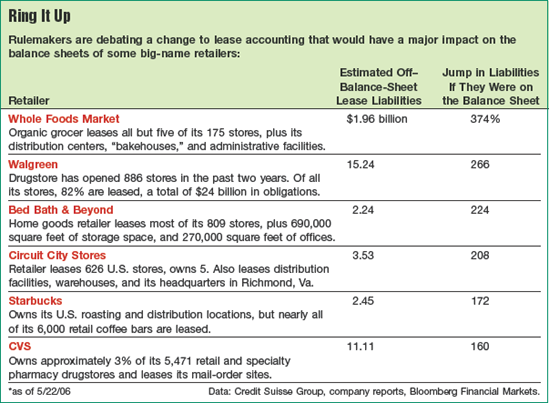

Off–Balance-Sheet Financing. Certain leases do not add debt on a balance sheet or affect financial ratios. In fact, they may add to borrowing capacity.[377] Such off–balance-sheet financing is critical to some companies.

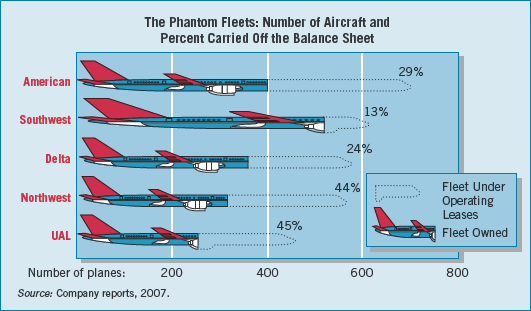

As shown in our opening story, airlines use lease arrangements extensively. This results in a great deal of off–balance-sheet financing. The following chart indicates that many airlines that lease aircraft understate debt levels by a substantial amount.

Airlines are not the only ones playing the off–balance-sheet game. A recent SEC study estimates that for SEC registrants, off–balance-sheet lease obligations total more the $1.3 trillion, or 31 times the amount of on–balance-sheet obligations. (See SEC Off–Balance Sheet report at www.sec.gov/news/studies/soxoffbalancerpt.pdf.) Thus, analysts must adjust reported debt levels for the effects of non-capitalized leases. A methodology for making this adjustment is discussed in Eugene A. Imhoff, Jr., Robert C. Lipe, and David W. Wright, "Operating Leases: Impact of Constructive Capitalization," Accounting Horizons (March 1991).

If Delta borrows $47 million on a 10-year note from Bank of America to purchase a Boeing 737 jet plane, Delta should clearly report an asset and related liability at that amount on its balance sheet. Similarly, if Delta purchases the 737 for $47 million directly from Boeing through an installment purchase over 10 years, it should obviously report an asset and related liability (i.e., it should "capitalize" the installment transaction).

However, what if Delta leases the Boeing 737 for 10 years from International Lease Finance Corp. (ILFC)—the world's largest lessor of airplanes—through a noncancelable lease transaction with payments of the same amount as the installment purchase transaction? In that case, opinion differs over how to report this transaction. The various views on capitalization of leases are as follows.

Do Not Capitalize Any Leased Assets. This view considers capitalization inappropriate, because Delta does not own the property. Furthermore, a lease is an "executory" contract requiring continuing performance by both parties. Because companies do not currently capitalize other executory contracts (such as purchase commitments and employment contracts), they should not capitalize leases either.

Capitalize Leases That Are Similar to Installment Purchases. This view holds that companies should report transactions in accordance with their economic substance. Therefore, if companies capitalize installment purchases, they should also capitalize leases that have similar characteristics. For example, Delta Airlines makes the same payments over a 10-year period for either a lease or an installment purchase. Lessees make rental payments, whereas owners make mortgage payments. Why should the financial statements not report these transactions in the same manner?

Capitalize All Long-Term Leases. This approach requires only the long-term right to use the property in order to capitalize. This property-rights approach capitalizes all long-term leases.[378]

Capitalize Firm Leases Where the Penalty for Nonperformance Is Substantial. A final approach advocates capitalizing only "firm" (noncancelable) contractual rights and obligations. "Firm" means that it is unlikely to avoid performance under the lease without a severe penalty.[379]

In short, the various viewpoints range from no capitalization to capitalization of all leases. The FASB apparently agrees with the capitalization approach when the lease is similar to an installment purchase: It notes that Delta should capitalize a lease that transfers substantially all of the benefits and risks of property ownership, provided the lease is noncancelable. Noncancelable means that Delta can cancel the lease contract only upon the outcome of some remote contingency, or that the cancellation provisions and penalties of the contract are so costly to Delta that cancellation probably will not occur.

This viewpoint leads to three basic conclusions: (1) Companies must identify the characteristics that indicate the transfer of substantially all of the benefits and risks of ownership. (2) The same characteristics should apply consistently to the lessee and the lessor. (3) Those leases that do not transfer substantially all the benefits and risks of ownership are operating leases. Companies should not capitalize operating leases. Instead, companies should account for them as rental payments and receipts.

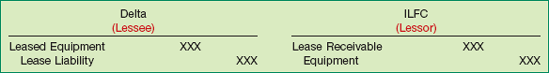

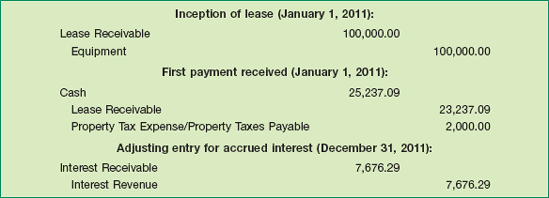

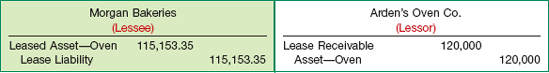

If Delta Airlines (the lessee) capitalizes a lease, it records an asset and a liability generally equal to the present value of the rental payments. ILFC (the lessor), having transferred substantially all the benefits and risks of ownership, recognizes a sale by removing the asset from the balance sheet and replacing it with a receivable. The typical journal entries for Delta and ILFC, assuming leased and capitalized equipment, appear as shown in Illustration 21-2.

Having capitalized the asset, Delta records depreciation on the leased asset. Both ILFC and Delta treat the lease rental payments as consisting of interest and principal.

If Delta does not capitalize the lease, it does not record an asset, nor does ILFC remove one from its books. When Delta makes a lease payment, it records rental expense; ILFC recognizes rental revenue.

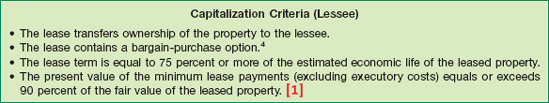

In order to record a lease as a capital lease, the lease must be noncancelable. Further, it must meet one or more of the four criteria listed in Illustration 21-3.

We define a bargain-purchase option in the next section.

Delta classifies and accounts for leases that do not meet any of the four criteria as operating leases. Illustration 21-4 shows that a lease meeting any one of the four criteria results in the lessee having a capital lease.

In keeping with the FASB's reasoning that a company consumes a significant portion of the value of the asset in the first 75 percent of its life, the lessee applies neither the third nor the fourth criterion when the inception of the lease occurs during the last 25 percent of the asset's life.

Three of the four capitalization criteria that apply to lessees are controversial and can be difficult to apply in practice. We discuss each of the criteria in detail on the following pages.

If the lease transfers ownership of the asset to the lessee, it is a capital lease. This criterion is not controversial and easily implemented in practice.

A bargain-purchase option allows the lessee to purchase the leased property for a price that is significantly lower than the property's expected fair value at the date the option becomes exercisable. At the inception of the lease, the difference between the option price and the expected fair market value must be large enough to make exercise of the option reasonably assured.

For example, assume that Brett's Delivery Service was to lease a Honda Accord for $599 per month for 40 months, with an option to purchase for $100 at the end of the 40-month period. If the estimated fair value of the Honda Accord is $3,000 at the end of the 40 months, the $100 option to purchase is clearly a bargain. Therefore, Brett must capitalize the lease. In other cases, the criterion may not be as easy to apply, and determining now that a certain future price is a bargain can be difficult.

If the lease period equals or exceeds 75 percent of the asset's economic life, the lessor transfers most of the risks and rewards of ownership to the lessee. Capitalization is therefore appropriate. However, determining the lease term and the economic life of the asset can be troublesome.

The lease term is generally considered to be the fixed, noncancelable term of the lease. However, a bargain-renewal option, if provided in the lease agreement, can extend this period. A bargain-renewal option allows the lessee to renew the lease for a rental that is lower than the expected fair rental at the date the option becomes exercisable. At the inception of the lease, the difference between the renewal rental and the expected fair rental must be great enough to make exercise of the option to renew reasonably assured.

For example, assume that Home Depot leases Dell PCs for two years at a rental of $100 per month per computer and subsequently can lease them for $10 per month per computer for another two years. The lease clearly offers a bargain-renewal option; the lease term is considered to be four years. However, with bargain-renewal options, as with bargain-purchase options, it is sometimes difficult to determine what is a bargain.[380]

Determining estimated economic life can also pose problems, especially if the leased item is a specialized item or has been used for a significant period of time. For example, determining the economic life of a nuclear core is extremely difficult. It is subject to much more than normal "wear and tear." As indicated earlier, the FASB takes the position that if the lease starts during the last 25 percent of the life of the asset, companies cannot use the economic life test to classify a lease as a capital lease.

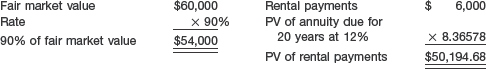

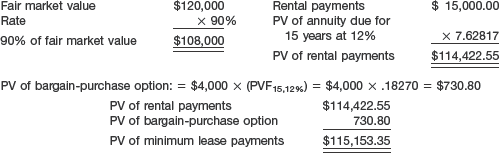

If the present value of the minimum lease payments equals or exceeds 90 percent of the fair market value of the asset, then a lessee like Delta should capitalize the leased asset. Why? If the present value of the minimum lease payments is reasonably close to the market price of the aircraft, Delta is effectively purchasing the asset.

Determining the present value of the minimum lease payments involves three important concepts: (1) minimum lease payments, (2) executory costs, and (3) discount rate.

Minimum Lease Payments. Delta is obligated to make, or expected to make, minimum lease payments in connection with the leased property. These payments include the following.

Minimum Rental Payments —Minimum rental payments are those that Delta must make to ILFC under the lease agreement. In some cases, the minimum rental payments may equal the minimum lease payments. However, the minimum lease payments may also include a guaranteed residual value (if any), penalty for failure to renew, or a bargain-purchase option (if any), as we note on the next page.

Guaranteed Residual Value—The residual value is the estimated fair (market) value of the leased property at the end of the lease term. ILFC may transfer the risk of loss to Delta or to a third party by obtaining a guarantee of the estimated residual value. The guaranteed residual value is either (1) the certain or determinable amount that Delta will pay ILFC at the end of the lease to purchase the aircraft at the end of the lease, or (2) the amount Delta or the third party guarantees that ILFC will realize if the aircraft is returned. (Third-party guarantors are, in essence, insurers who for a fee assume the risk of deficiencies in leased asset residual value.) If not guaranteed in full, the unguaranteed residual value is the estimated residual value exclusive of any portion guaranteed.[381]

Penalty for Failure to Renew or Extend the Lease —The amount Delta must pay if the agreement specifies that it must extend or renew the lease, and it fails to do so.

Bargain-Purchase Option —As we indicated earlier (in item 1), an option given to Delta to purchase the aircraft at the end of the lease term at a price that is fixed sufficiently below the expected fair value, so that, at the inception of the lease, purchase is reasonably assured.

Delta excludes executory costs (defined below) from its computation of the present value of the minimum lease payments.

Executory Costs. Like most assets, leased tangible assets incur insurance, maintenance, and tax expenses—called executory costs—during their economic life. If ILFC retains responsibility for the payment of these "ownership-type costs," it should exclude, in computing the present value of the minimum lease payments, a portion of each lease payment that represents executory costs. Executory costs do not represent payment on or reduction of the obligation.

Many lease agreements specify that the lessee directly pays executory costs to the appropriate third parties. In these cases, the lessor can use the rental payment without adjustment in the present value computation.

Discount Rate. A lessee, like Delta, generally computes the present value of the minimum lease payments using its incremental borrowing rate. This rate is defined as: "The rate that, at the inception of the lease, the lessee would have incurred to borrow the funds necessary to buy the leased asset on a secured loan with repayment terms similar to the payment schedule called for in the lease." [4]

To determine whether the present value of these payments is less than 90 percent of the fair market value of the property, Delta discounts the payments using its incremental borrowing rate. Determining the incremental borrowing rate often requires judgment because the lessee bases it on a hypothetical purchase of the property.

However, there is one exception to this rule. If (1) Delta knows the implicit interest rate computed by ILFC and (2) it is less than Delta's incremental borrowing rate, then Delta must use ILFC's implicit rate. What is the interest rate implicit in the lease? It is the discount rate that, when applied to the minimum lease payments and any un-guaranteed residual value accruing to the lessor, causes the aggregate present value to equal the fair value of the leased property to the lessor. [5]

The purpose of this exception is twofold. First, the implicit rate of ILFC is generally a more realistic rate to use in determining the amount (if any) to report as the asset and related liability for Delta. Second, the guideline ensures that Delta does not use an artificially high incremental borrowing rate that would cause the present value of the minimum lease payments to be less than 90 percent of the fair market value of the aircraft. Use of such a rate would thus make it possible to avoid capitalization of the asset and related liability.

Delta may argue that it cannot determine the implicit rate of the lessor and therefore should use the higher rate. However, in most cases, Delta can approximate the implicit rate used by ILFC. The determination of whether or not a reasonable estimate could be made will require judgment, particularly where the result from using the incremental borrowing rate comes close to meeting the 90 percent test. Because Delta may not capitalize the leased property at more than its fair value (as we discuss later), it cannot use an excessively low discount rate.

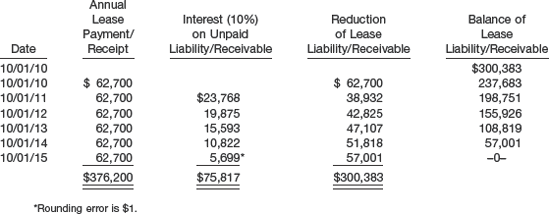

In a capital lease transaction, Delta uses the lease as a source of financing. ILFC finances the transaction (provides the investment capital) through the leased asset. Delta makes rent payments, which actually are installment payments. Therefore, over the life of the aircraft rented, the rental payments to ILFC constitute a payment of principal plus interest.

Under the capital lease method, Delta treats the lease transaction as if it purchases the aircraft in a financing transaction. That is, Delta acquires the aircraft and creates an obligation. Therefore, it records a capital lease as an asset and a liability at the lower of (1) the present value of the minimum lease payments (excluding executory costs) or (2) the fair value of the leased asset at the inception of the lease. The rationale for this approach is that companies should not record a leased asset for more than its fair value.

One troublesome aspect of accounting for the depreciation of the capitalized leased asset relates to the period of depreciation. If the lease agreement transfers ownership of the asset to Delta (criterion 1) or contains a bargain-purchase option (criterion 2), Delta depreciates the aircraft consistent with its normal depreciation policy for other aircraft, using the economic life of the asset.

On the other hand, if the lease does not transfer ownership or does not contain a bargain purchase option, then Delta depreciates it over the term of the lease. In this case, the aircraft reverts to ILFC after a certain period of time.

Throughout the term of the lease, Delta uses the effective-interest method to allocate each lease payment between principal and interest. This method produces a periodic interest expense equal to a constant percentage of the carrying value of the lease obligation. When applying the effective-interest method to capital leases, Delta must use the same discount rate that determines the present value of the minimum lease payments.

Although Delta computes the amounts initially capitalized as an asset and recorded as an obligation at the same present value, the depreciation of the aircraft and the discharge of the obligation are independent accounting processes during the term of the lease. It should depreciate the leased asset by applying conventional depreciation methods: straight-line, sum-of-the-years'-digits, declining-balance, units of production, etc. The FASB uses the term "amortization" more frequently than "depreciation" to recognize intangible leased property rights. We prefer "depreciation" to describe the write-off of a tangible asset's expired services.

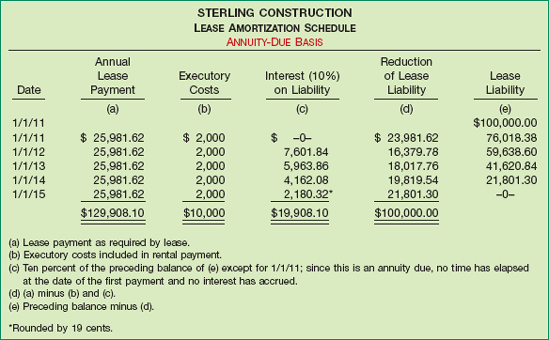

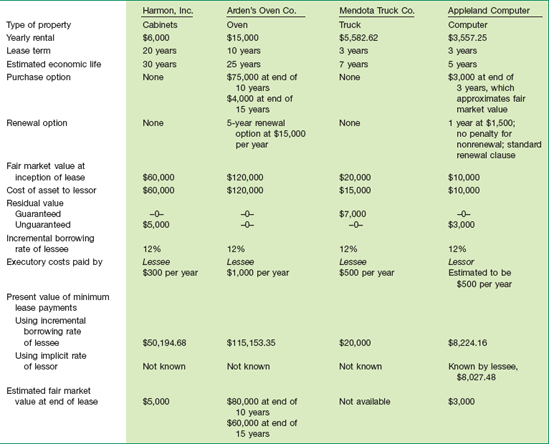

To illustrate a capital lease, assume that Caterpillar Financial Services Corp. (a subsidiary of Caterpillar) and Sterling Construction Corp. sign a lease agreement dated January 1, 2011, that calls for Caterpillar to lease a front-end loader to Sterling beginning January 1, 2011. The terms and provisions of the lease agreement, and other pertinent data, are as follows.

The term of the lease is five years. The lease agreement is noncancelable, requiring equal rental payments of $25,981.62 at the beginning of each year (annuity due basis).

The loader has a fair value at the inception of the lease of $100,000, an estimated economic life of five years, and no residual value.

Sterling pays all of the executory costs directly to third parties except for the property taxes of $2,000 per year, which is included as part of its annual payments to Caterpillar.

The lease contains no renewal options. The loader reverts to Caterpillar at the termination of the lease.

Sterling's incremental borrowing rate is 11 percent per year.

Sterling depreciates, on a straight-line basis, similar equipment that it owns.

Caterpillar sets the annual rental to earn a rate of return on its investment of 10 percent per year; Sterling knows this fact.

The lease meets the criteria for classification as a capital lease for the following reasons:

The lease term of five years, being equal to the equipment's estimated economic life of five years, satisfies the 75 percent test.

The present value of the minimum lease payments ($100,000 as computed below) exceeds 90 percent of the fair value of the loader ($100,000).

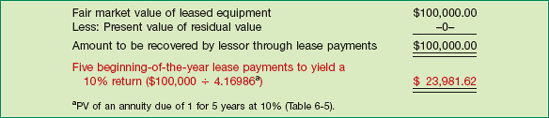

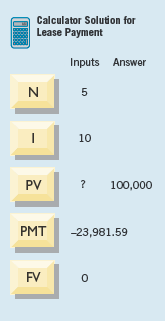

The minimum lease payments are $119,908.10 ($23,981.62 × 5). Sterling computes the amount capitalized as leased assets as the present value of the minimum lease payments (excluding executory costs—property taxes of $2,000) as shown in Illustration 21-5.

Sterling uses Caterpillar's implicit interest rate of 10 percent instead of its incremental borrowing rate of 11 percent because (1) it is lower and (2) it knows about it.[382] Sterling records the capital lease on its books on January 1, 2011, as:

Note that the entry records the obligation at the net amount of $100,000 (the present value of the future rental payments) rather than at the gross amount of $119,908.10 ($23,981.62 × 5).

Sterling records the first lease payment on January 1, 2011, as follows:

Each lease payment of $25,981.62 consists of three elements: (1) a reduction in the lease liability, (2) a financing cost (interest expense), and (3) executory costs (property taxes). The total financing cost (interest expense) over the term of the lease is $19,908.10. This amount is the difference between the present value of the lease payments ($100,000) and the actual cash disbursed, net of executory costs ($119,908.10). Therefore, the annual interest expense, applying the effective-interest method, is a function of the outstanding liability, as Illustration 21-6 shows.

At the end of its fiscal year, December 31, 2011, Sterling records accrued interest as follows.

Depreciation of the leased equipment over its five-year lease term, applying Sterling's normal depreciation policy (straight-line method), results in the following entry on December 31, 2011.

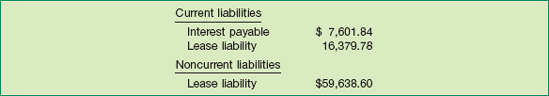

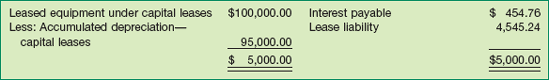

At December 31, 2011, Sterling separately identifies the assets recorded under capital leases on its balance sheet. Similarly, it separately identifies the related obligations. Sterling classifies the portion due within one year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer, with current liabilities, and the rest with noncurrent liabilities. For example, the current portion of the December 31, 2011, total obligation of $76,018.38 in Sterling's amortization schedule is the amount of the reduction in the obligation in 2012, or $16,379.78. Illustration 21-7 shows the liabilities section as it relates to lease transactions at December 31, 2011.

Sterling records the lease payment of January 1, 2012, as follows.

Entries through 2015 would follow the pattern above. Sterling records its other executory costs (insurance and maintenance) in a manner similar to how it records any other operating costs incurred on assets it owns.

Upon expiration of the lease, Sterling has fully amortized the amount capitalized as leased equipment. It also has fully discharged its lease obligation. If Sterling does not purchase the loader, it returns the equipment to Caterpillar. Sterling then removes the leased equipment and related accumulated depreciation accounts from its books.[383]

If Sterling purchases the equipment at termination of the lease, at a price of $5,000 and the estimated life of the equipment changes from five to seven years, it makes the following entry.

Under the operating method, rent expense (and the associated liability) accrues day by day to the lessee as it uses the property. The lessee assigns rent to the periods benefiting from the use of the asset and ignores, in the accounting, any commitments to make future payments. The lessee makes appropriate accruals or deferrals if the accounting period ends between cash payment dates.

For example, assume that the capital lease illustrated in the previous section did not qualify as a capital lease. Sterling therefore accounts for it as an operating lease. The first-year charge to operations is now $25,981.62, the amount of the rental payment. Sterling records this payment on January 1, 2011, as follows.

Sterling does not report the loader, as well as any long-term liability for future rental payments, on the balance sheet. Sterling reports rent expense on the income statement. And, as discussed later in the chapter, Sterling must disclose all operating leases that have noncancelable lease terms in excess of one year.

As we indicated, if accounting for the lease as an operating lease, the first-year charge to operations is $25,981.62, the amount of the rental payment. Treating the transaction as a capital lease, however, results in a first-year charge of $29,601.84: depreciation of $20,000 (assuming straight-line), interest expense of $7,601.84 (per Illustration 21-6), and executory costs of $2,000. Illustration 21-8 shows that while the total charges to operations are the same over the lease term whether accounting for the lease as a capital lease or as an operating lease, under the capital lease treatment the charges are higher in the earlier years and lower in the later years.[384]

If using an accelerated method of depreciation, the differences between the amounts charged to operations under the two methods would be even larger in the earlier and later years.

In addition, using the capital lease approach results in an asset and related liability of $100,000 initially reported on the balance sheet. The lessee would not report any asset or liability under the operating method. Therefore, the following differences occur if using a capital lease instead of an operating lease:

An increase in the amount of reported debt (both short-term and long-term).

An increase in the amount of total assets (specifically long-lived assets).

A lower income early in the life of the lease and, therefore, lower retained earnings.

Thus, many companies believe that capital leases negatively impact their financial position: Their debt to total equity ratio increases, and their rate of return on total assets decreases. As a result, the business community resists capitalizing leases.

Whether this resistance is well founded is debatable. From a cash flow point of view, the company is in the same position whether accounting for the lease as an operating or a capital lease. Managers often argue against capitalization for several reasons: First is that capitalization can more easily lead to violation of loan covenants. It also can affect the amount of compensation received by owners (for example, a stock compensation plan tied to earnings). Finally, capitalization can lower rates of return and increase debt to equity relationships, making the company less attractive to present and potential investors.[385]

Under current accounting rules, companies can keep the obligations associated with operating leases off the balance sheet. (For example, see the "What Do the Numbers Mean?" box on page 1115 for the effects of this approach for airlines.) This approach may change if the IASB and FASB are able to craft a new lease-accounting rule. The current plans for a new rule in this area should result in many more operating leases on balance sheets. Analysts are beginning to estimate the expected impact of a new rule. As shown in the table below, if the IASB and FASB issue a new rule on operating leases, a company like Whole Foods could see its liabilities jump a whopping 374 percent.

This is not a pretty picture, but investors need to see it if they are to fully understand a company's lease obligations.

Source: Nanette Byrnes, "You May Be Liable for That Lease," BusinessWeek (June 5, 2006), p. 76.

Earlier in this chapter we discussed leasing's advantages to the lessee. Three important benefits are available to the lessor:

Interest Revenue. Leasing is a form of financing. Banks, captives, and independent leasing companies find leasing attractive because it provides competitive interest margins.

Tax Incentives. In many cases, companies that lease cannot use the tax benefit of the asset, but leasing allows them to transfer such tax benefits to another party (the lessor) in return for a lower rental rate on the leased asset. To illustrate, Boeing Aircraft might sell one of its 737 jet planes to a wealthy investor who needed only the tax benefit. The investor then leased the plane to a foreign airline, for whom the tax benefit was of no use. Everyone gained. Boeing sold its airplane, the investor received the tax benefit, and the foreign airline cheaply acquired a 737.[386]

High Residual Value. Another advantage to the lessor is the return of the property at the end of the lease term. Residual values can produce very large profits. Citigroup at one time assumed that the commercial aircraft it was leasing to the airline industry would have a residual value of 5 percent of their purchase price. It turned out that they were worth 150 percent of their cost—a handsome profit. At the same time, if residual values decline, lessors can suffer losses when less-valuable leased assets are returned at the conclusion of the lease. Recently, automaker Ford took a $2.1 billion write-down on its lease portfolio, when rising gas prices spurred dramatic declines in the resale values of leased trucks and SUVs. Such residual value losses led Chrysler to get out of the leasing business altogether.

A lessor, such as Caterpillar Financial in our earlier example, determines the amount of the rental, basing it on the rate of return—the implicit rate—needed to justify leasing the front-end loader. In establishing the rate of return, Caterpillar considers the credit standing of Sterling Construction, the length of the lease, and the status of the residual value (guaranteed versus unguaranteed).

In the Caterpillar/Sterling example on pages 1124–1127, Caterpillar's implicit rate was 10 percent, the cost of the equipment to Caterpillar was $100,000 (also fair market value), and the estimated residual value was zero. Caterpillar determines the amount of the lease payment as follows.

If a residual value is involved (whether guaranteed or not), Caterpillar would not have to recover as much from the lease payments. Therefore, the lease payments would be less. (Illustration 21-16, on page 1136, shows this situation.)

For accounting purposes, the lessor may classify leases as one of the following:

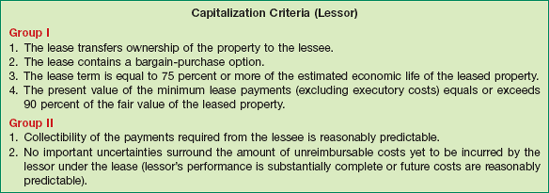

Illustration 21-10 presents two groups of capitalization criteria for the lessor. If at the date of inception, the lessor agrees to a lease that meets one or more of the Group I criteria (1, 2, 3, and 4) and both of the Group II criteria (1 and 2), the lessor shall classify and account for the arrangement as a direct-financing lease or as a sales-type lease. [7] (Note that the Group I criteria are identical to the criteria that must be met in order for a lessee to classify a lease as a capital lease, as shown in Illustration 21-3 on page 1121.)

Why the Group II requirements? The profession wants to ensure that the lessor has really transferred the risks and benefits of ownership. If collectibility of payments is not predictable or if performance by the lessor is incomplete, then the criteria for revenue recognition have not been met. The lessor should therefore account for the lease as an operating lease.

For example, computer leasing companies at one time used to buy IBM equipment, lease the equipment, and remove the leased assets from their balance sheets. In leasing the assets, the computer lessors stated that they would substitute new IBM equipment if obsolescence occurred. However, when IBM introduced a new computer line, IBM refused to sell it to the computer leasing companies. As a result, a number of the lessors could not meet their contracts with their customers and had to take back the old equipment. The computer leasing companies therefore had to reinstate the assets they had taken off the books. Such a case demonstrates one reason for the Group II requirements.

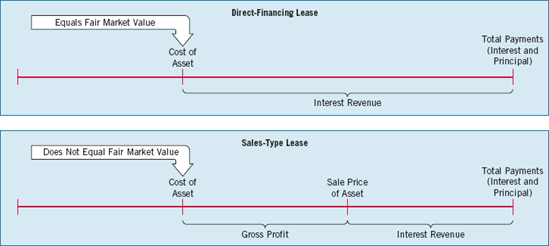

The distinction for the lessor between a direct-financing lease and a sales-type lease is the presence or absence of a manufacturer's or dealer's profit (or loss) : A sales-type lease involves a manufacturer's or dealer's profit, and a direct-financing lease does not. The profit (or loss) to the lessor is evidenced by the difference between the fair value of the leased property at the inception of the lease and the lessor's cost or carrying amount (book value).

Normally, sales-type leases arise when manufacturers or dealers use leasing as a means of marketing their products. For example, a computer manufacturer will lease its computer equipment (possibly through a captive) to businesses and institutions. Direct-financing leases generally result from arrangements with lessors that are primarily engaged in financing operations (e.g., banks). However, a lessor need not be a manufacturer or dealer to recognize a profit (or loss) at the inception of a lease that requires application of sales-type lease accounting.

Lessors classify and account for all leases that do not qualify as direct-financing or sales-type leases as operating leases. Illustration 21-11 shows the circumstances under which a lessor classifies a lease as operating, direct-financing, or sales-type.

As a consequence of the additional Group II criteria for lessors, a lessor may classify a lease as an operating lease but the lessee may classify the same lease as a capital lease. In such an event, both the lessor and lessee will carry the asset on their books, and both will depreciate the capitalized asset.

For purposes of comparison with the lessee's accounting, we will illustrate only the operating and direct-financing leases in the following section. We will discuss the more complex sales-type lease later in the chapter.

Direct-financing leases are in substance the financing of an asset purchase by the lessee. In this type of lease, the lessor records a lease receivable instead of a leased asset. The lease receivable is the present value of the minimum lease payments. Remember that "minimum lease payments" include:

Rental payments (excluding executory costs).

Bargain-purchase option (if any).

Guaranteed residual value (if any).

Penalty for failure to renew (if any).

Thus, the lessor records the residual value, whether guaranteed or not. Also, recall that if the lessor pays any executory costs, then it should reduce the rental payment by that amount in computing minimum lease payments.

The following presentation, using the data from the preceding Caterpillar/Sterling example on pages 1124–1127, illustrates the accounting treatment for a direct-financing lease. We repeat here the information relevant to Caterpillar in accounting for this lease transaction.

The term of the lease is five years beginning January 1, 2011, noncancelable, and requires equal rental payments of $25,981.62 at the beginning of each year. Payments include $2,000 of executory costs (property taxes).

The equipment (front-end loader) has a cost of $100,000 to Caterpillar, a fair value at the inception of the lease of $100,000, an estimated economic life of five years, and no residual value.

Caterpillar incurred no initial direct costs in negotiating and closing the lease transaction.

The lease contains no renewal options. The equipment reverts to Caterpillar at the termination of the lease.

Collectibility is reasonably assured and Caterpillar incurs no additional costs (with the exception of the property taxes being collected from Sterling).

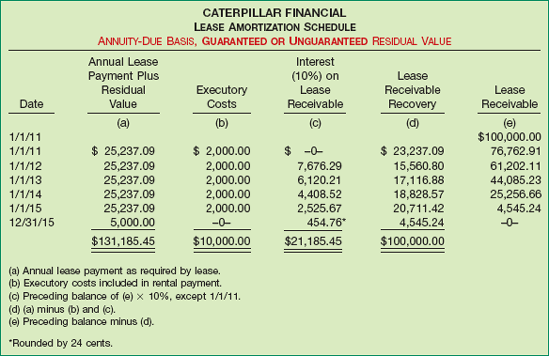

Caterpillar sets the annual lease payments to ensure a rate of return of 10 percent (implicit rate) on its investment as shown in Illustration 21-12.

The lease meets the criteria for classification as a direct-financing lease for several reasons: (1) The lease term exceeds 75 percent of the equipment's estimated economic life. (2) The present value of the minimum lease payments exceeds 90 percent of the equipment's fair value. (3) Collectibility of the payments is reasonably assured. And (4) Caterpillar incurs no further costs. It is not a sales-type lease because there is no difference between the fair value ($100,000) of the loader and Caterpillar's cost ($100,000).

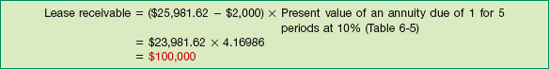

The Lease Receivable is the present value of the minimum lease payments (excluding executory costs which are property taxes of $2,000). Caterpillar computes it as follows.

Caterpillar records the lease of the asset and the resulting receivable on January 1, 2011 (the inception of the lease), as follows.

Companies often report the lease receivable in the balance sheet as "Net investment in capital leases." Companies classify it either as current or noncurrent, depending on when they recover the net investment.[387]

Caterpillar replaces its investment (the leased front-end loader, a cost of $100,000), with a lease receivable. In a manner similar to Sterling's treatment of interest, Caterpillar applies the effective-interest method and recognizes interest revenue as a function of the lease receivable balance, as Illustration 21-14 (on page 1134) shows.

On January 1, 2011, Caterpillar records receipt of the first year's lease payment as follows.

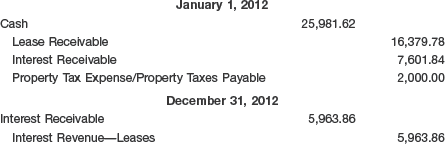

On December 31, 2011, Caterpillar recognizes the interest revenue earned during the first year through the following entry.

At December 31, 2011, Caterpillar reports the lease receivable in its balance sheet among current assets or noncurrent assets, or both. It classifies the portion due within one year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer, as a current asset, and the rest with noncurrent assets.

Illustration 21-15 shows the assets section as it relates to lease transactions at December 31, 2011.

The following entries record receipt of the second year's lease payment and recognition of the interest earned.

Journal entries through 2015 follow the same pattern except that Caterpillar records no entry in 2015 (the last year) for earned interest. Because it fully collects the receivable by January 1, 2015, no balance (investment) is outstanding during 2015. Caterpillar recorded no depreciation. If Sterling buys the loader for $5,000 upon expiration of the lease, Caterpillar recognizes disposition of the equipment as follows.

Under the operating method, the lessor records each rental receipt as rental revenue. It depreciates the leased asset in the normal manner, with the depreciation expense of the period matched against the rental revenue. The amount of revenue recognized in each accounting period is a level amount (straight-line basis) regardless of the lease provisions, unless another systematic and rational basis better represents the time pattern in which the lessor derives benefit from the leased asset.

In addition to the depreciation charge, the lessor expenses maintenance costs and the cost of any other services rendered under the provisions of the lease that pertain to the current accounting period. The lessor amortizes over the life of the lease any costs paid to independent third parties, such as appraisal fees, finder's fees, and costs of credit checks, usually on a straight-line basis.

To illustrate the operating method, assume that the direct-financing lease illustrated in the previous section does not qualify as a capital lease. Therefore, Caterpillar accounts for it as an operating lease. It records the cash rental receipt, assuming the $2,000 was for property tax expense, as follows.

Caterpillar records depreciation as follows (assuming a straight-line method, a cost basis of $100,000, and a five-year life).

If Caterpillar pays property taxes, insurance, maintenance, and other operating costs during the year, it records them as expenses chargeable against the gross rental revenues.

If Caterpillar owns plant assets that it uses in addition to those leased to others, the company separately classifies the leased equipment and accompanying accumulated depreciation as Equipment Leased to Others or Investment in Leased Property. If significant in amount or in terms of activity, Caterpillar separates the rental revenues and accompanying expenses in the income statement from sales revenue and cost of goods sold.

The features of lease arrangements that cause unique accounting problems are:

Residual values.

Sales-type leases (lessor).

Bargain-purchase options.

Initial direct costs.

Current versus noncurrent classification.

Disclosure.

We discuss each of these features on the following pages.

Up to this point, in order to develop the basic accounting issues related to lessee and lessor accounting, we have generally ignored residual values. Accounting for residual values is complex and will probably provide you with the greatest challenge in understanding lease accounting.

The residual value is the estimated fair value of the leased asset at the end of the lease term. Frequently, a significant residual value exists at the end of the lease term, especially when the economic life of the leased asset exceeds the lease term. If title does not pass automatically to the lessee (criterion 1) and a bargain-purchase option does not exist (criterion 2), the lessee returns physical custody of the asset to the lessor at the end of the lease term.[388]

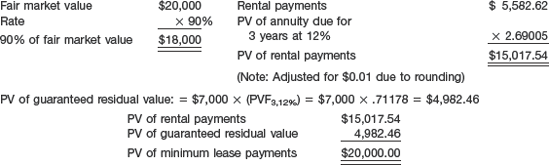

The residual value may be unguaranteed or guaranteed by the lessee. Sometimes the lessee agrees to make up any deficiency below a stated amount that the lessor realizes in residual value at the end of the lease term. In such a case, that stated amount is the guaranteed residual value.

The parties to a lease use guaranteed residual value in lease arrangements for two reasons. The first is a business reason: It protects the lessor against any loss in estimated residual value, thereby ensuring the lessor of the desired rate of return on investment. The second reason is an accounting benefit that you will learn from the discussion at the end of this chapter.

A guaranteed residual value—by definition—has more assurance of realization than does an unguaranteed residual value. As a result, the lessor may adjust lease payments because of the increased certainty of recovery. After the lessor establishes this rate, it makes no difference from an accounting point of view whether the residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed. The net investment that the lessor records (once the rate is set) will be the same.

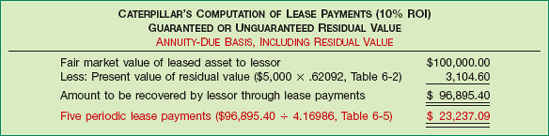

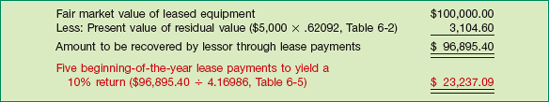

Assume the same data as in the Caterpillar/Sterling illustrations except that Caterpillar estimates a residual value of $5,000 at the end of the five-year lease term. In addition, Caterpillar assumes a 10 percent return on investment (ROI),[389] whether the residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed. Caterpillar would compute the amount of the lease payments as follows.

Contrast the foregoing lease payment amount to the lease payments of $23,981.62 as computed in Illustration 21-9 (on page 1130), where no residual value existed. In the second example, the payments are less, because the present value of the residual value reduces Caterpillar's total recoverable amount from $100,000 to $96,895.40.

Whether the estimated residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed has both economic and accounting consequence to the lessee. We saw the economic consequence— lower lease payments—in the preceding example. The accounting consequence is that the minimum lease payments, the basis for capitalization, include the guaranteed residual value but excludes the unguaranteed residual value.

Guaranteed Residual Value (Lessee Accounting). A guaranteed residual value affects the lessee's computation of minimum lease payments. Therefore it also affects the amounts capitalized as a leased asset and a lease obligation. In effect, the guaranteed residual value is an additional lease payment that the lessee will pay in property or cash, or both, at the end of the lease term.

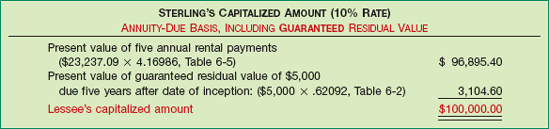

Using the rental payments as computed by the lessor in Illustration 21-16, the minimum lease payments are $121,185.45 ([$23,237.09 × 5] + $5,000). Illustration 21-17 shows the capitalized present value of the minimum lease payments (excluding executory costs) for Sterling Construction.

Sterling prepares a schedule of interest expense and amortization of the $100,000 lease liability. That schedule, shown in Illustration 21-18, is based on a $5,000 final guaranteed residual value payment at the end of five years.

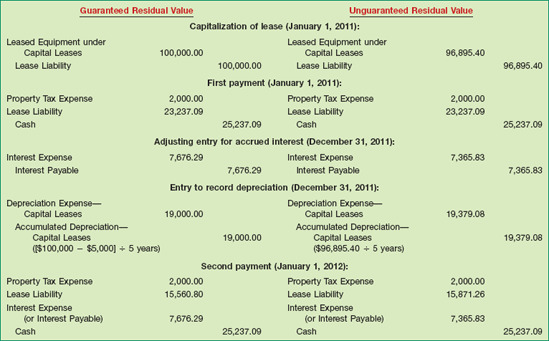

Sterling records the leased asset (front-end loader) and liability, depreciation, interest, property tax, and lease payments on the basis of a guaranteed residual value. (These journal entries are shown in Illustration 21-23, on page 1140.) The format of these entries is the same as illustrated earlier, although the amounts are different because of the guaranteed residual value. Sterling records the loader at $100,000 and depreciates it over five years. To compute depreciation, it subtracts the guaranteed residual value from the cost of the loader. Assuming that Sterling uses the straight-line method, the depreciation expense each year is $19,000 ([$100,000 − $5,000] ÷ 5 years).

At the end of the lease term, before the lessee transfers the asset to Caterpillar, the lease asset and liability accounts have the following balances.

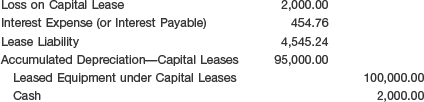

If, at the end of the lease, the fair market value of the residual value is less than $5,000, Sterling will have to record a loss. Assume that Sterling depreciated the leased asset down to its residual value of $5,000 but that the fair market value of the residual value at December 31, 2015, was $3,000. In this case, Sterling would have to report a loss of $2,000. Assuming that it pays cash to make up the residual value deficiency, Sterling would make the following journal entry.

If the fair market value exceeds $5,000, a gain may be recognized. Caterpillar and Sterling may apportion gains on guaranteed residual values in whatever ratio the parties initially agree.

When there is a guaranteed residual value, the lessee must be careful not to depreciate the total cost of the asset. For example, if Sterling mistakenly depreciated the total cost of the loader ($100,000), a misstatement would occur. That is, the carrying amount of the asset at the end of the lease term would be zero, but Sterling would show the liability under the capital lease at $5,000. In that case, if the asset was worth $5,000, Sterling would end up reporting a gain of $5,000 when it transferred the asset back to Caterpillar. As a result, Sterling would overstate depreciation and would understate net income in 2011–2014; in the last year (2015) net income would be overstated.

Unguaranteed Residual Value (Lessee Accounting). From the lessee's viewpoint, an unguaranteed residual value is the same as no residual value in terms of its effect upon the lessee's method of computing the minimum lease payments and the capitalization of the leased asset and the lease liability.

Assume the same facts as those above except that the $5,000 residual value is unguaranteed instead of guaranteed. The amount of the annual lease payments would be the same—$23,237.09. Whether the residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed, Caterpillar will recover the same amount through lease rentals—that is, $96,895.40. The minimum lease payments are $116,185.45 ($23,237.09 × 5). Lessee Company would capitalize the amount shown in Illustration 21-20.

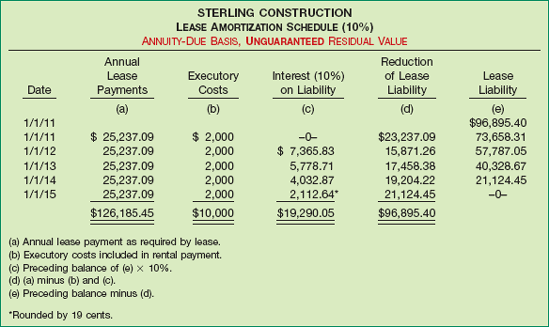

Illustration 21-21 shows Sterling's schedule of interest expense and amortization of the lease liability of $96,895.40, assuming an unguaranteed residual value of $5,000 at the end of five years.

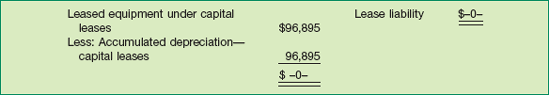

Sterling records the leased asset and liability, depreciation, interest, property tax, and lease payments on the basis of an unguaranteed residual value. (These journal entries are shown in Illustration 21-23, on page 1140.) The format of these capital lease entries is the same as illustrated earlier. Note that Sterling records the leased asset at $96,895.40 and depreciates it over five years. Assuming that it uses the straight-line method, the depreciation expense each year is $19,379.08 ($96,895.40 ÷ 5 years). At the end of the lease term, before Sterling transfers the asset to Caterpillar, the lease asset and liability accounts have the following balances.

Assuming that Sterling has fully depreciated the leased asset and has fully amortized the lease liability, no entry is required at the end of the lease term, except to remove the asset from the books.

If Sterling depreciated the asset down to its unguaranteed residual value, a mis-statement would occur. That is, the carrying amount of the leased asset would be $5,000 at the end of the lease, but the liability under the capital lease would be stated at zero before the transfer of the asset. Thus, Sterling would end up reporting a loss of $5,000 when it transferred the asset back to Caterpillar. Sterling would understate depreciation and would overstate net income in 2011–2014; in the last year (2015) net income would be understated because of the recorded loss.

Lessee Entries Involving Residual Values. Illustration 21-23 shows, in comparative form, Sterling's entries for both a guaranteed and an unguaranteed residual value.

As we indicated earlier, the lessor will recover the same net investment whether the residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed. That is, the lessor works on the assumption that it will realize the residual value at the end of the lease term whether guaranteed or unguaranteed. The lease payments required in order for the company to earn a certain return on investment are the same (e.g., $23,237.09 in our example) whether the residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed.

To illustrate, we again use the Caterpillar/Sterling data and assume classification of the lease as a direct-financing lease. With a residual value (either guaranteed or unguaranteed) of $5,000, Caterpillar determines the payments as follows.

The amortization schedule is the same for guaranteed or unguaranteed residual value, as Illustration 21-25 shows.

Using the amounts computed above, Caterpillar would make the following entries for this direct-financing lease in the first year. Note the similarity to Sterling's entries in Illustration 21-23.

As already indicated, the primary difference between a direct-financing lease and a sales-type lease is the manufacturer's or dealer's gross profit (or loss). The diagram in Illustration 21-27 (on page 1142) presents the distinctions between direct-financing and sales-type leases.

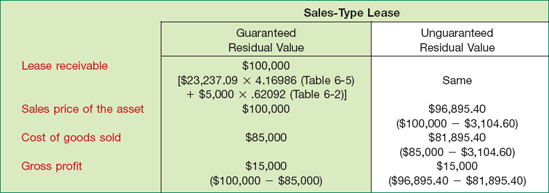

In a sales-type lease, the lessor records the sale price of the asset, the cost of goods sold and related inventory reduction, and the lease receivable. The information necessary to record the sales-type lease is as follows.

When recording sales revenue and cost of goods sold, there is a difference in the accounting for guaranteed and unguaranteed residual values. The guaranteed residual value can be considered part of sales revenue because the lessor knows that the entire asset has been sold. But there is less certainty that the unguaranteed residual portion of the asset has been "sold" (i.e., will be realized). Therefore, the lessor recognizes sales and cost of goods sold only for the portion of the asset for which realization is assured. However, the gross profit amount on the sale of the asset is the same whether a guaranteed or unguaranteed residual value is involved.

To illustrate a sales-type lease with a guaranteed residual value and with an un-guaranteed residual value, assume the same facts as in the preceding direct-financing lease situation (pages 1132–1135). The estimated residual value is $5,000 (the present value of which is $3,104.60), and the leased equipment has an $85,000 cost to the dealer, Caterpillar. Assume that the fair market value of the residual value is $3,000 at the end of the lease term.

Illustration 21-28 shows computation of the amounts relevant to a sales-type lease.

Caterpillar records the same profit ($15,000) at the point of sale whether the residual value is guaranteed or unguaranteed. The difference between the two is that the sales revenue and cost of goods sold amounts are different.

In making this computation, we deduct the present value of the unguaranteed residual value from sales revenue and cost of goods sold for two reasons: (1) The criteria for revenue recognition have not been met. (2) It is improper to match expense against revenue not yet recognized. The revenue recognition criteria have not been met because of the uncertainty surrounding the realization of the unguaranteed residual value.

Caterpillar makes the following entries to record this transaction on January 1, 2011, and the receipt of the residual value at the end of the lease term.

Figure 21-29. Entries for Guaranteed and Unguaranteed Residual Values, Lessor Company—Sales-Type Lease

Companies must periodically review the estimated unguaranteed residual value in a sales-type lease. If the estimate of the unguaranteed residual value declines, the company must revise the accounting for the transaction using the changed estimate. The decline represents a reduction in the lessor's lease receivable (net investment). The lessor recognizes the decline as a loss in the period in which it reduces the residual estimate. Companies do not recognize upward adjustments in estimated residual value.

Xerox derives much of its income from leasing equipment. Reporting such leases as sales leases, Xerox records a lease contract as a sale, therefore recognizing income immediately. One problem is that each lease receipt consists of payments for items such as supplies, services, financing, and equipment.

The SEC accused Xerox of inappropriately allocating lease receipts, which affects the timing of income that it reports. If Xerox applied SEC guidelines, it would report income in different time periods. Xerox contended that its methods were correct. It also noted that when the lease term is up, the bottom line is the same using either the SEC's recommended allocation method or its current method.

Although Xerox can refuse to change its method, the SEC has the right to prevent a company from selling stock or bonds to the public if the agency rejects filings of the company.

Apparently, being able to access public markets is very valuable to Xerox. The company agreed to change its accounting according to SEC wishes, and Xerox will pay $670 million to settle a shareholder lawsuit related to its lease transactions. Its former auditor, KPMG LLP, will pay $80 million.

Source: Adapted from "Xerox Takes on the SEC," Accounting Web (January 9, 2002) (www.account-ingweb.com); and K. Shwiff and M. Maremont, "Xerox, KPMG Settle Shareholder Lawsuit," Wall Street Journal Online (March 28, 2008), p. B3.

As stated earlier, a bargain-purchase option allows the lessee to purchase the leased property for a future price that is substantially lower than the property's expected future fair value. The price is so favorable at the lease's inception that the future exercise of the option appears to be reasonably assured. If a bargain-purchase option exists, the lessee must increase the present value of the minimum lease payments by the present value of the option price.

For example, assume that Sterling Construction in Illustration 21-18 on page 1137 had an option to buy the leased equipment for $5,000 at the end of the five-year lease term. At that point, Sterling and Caterpillar expect the fair value to be $18,000. The significant difference between the option price and the fair value creates a bargain-purchase option, and the exercise of that option is reasonably assured.

A bargain-purchase option affects the accounting for leases in essentially the same way as a guaranteed residual value. In other words, with a guaranteed residual value, the lessee must pay the residual value at the end of the lease. Similarly, a purchase option that is a bargain will almost certainly be paid by the lessee. Therefore, the computations, amortization schedule, and entries that would be prepared for this $5,000 bargain-purchase option are identical to those shown for the $5,000 guaranteed residual value (see Illustrations 21-16, 21-17, and 21-18 on pages 1136 and 1137).

The only difference between the accounting treatment for a bargain-purchase option and a guaranteed residual value of identical amounts and circumstances is in the computation of the annual depreciation. In the case of a guaranteed residual value, Sterling depreciates the asset over the lease term; in the case of a bargain-purchase option, it uses the economic life of the asset.

Initial direct costs are of two types: incremental and internal. [8] Incremental direct costs are paid to independent third parties for originating a lease arrangement. Examples include the cost of independent appraisal of collateral used to secure a lease, the cost of an outside credit check of the lessee, or a broker's fee for finding the lessee.

Internal direct costs are directly related to specified activities performed by the lessor on a given lease. Examples are evaluating the prospective lessee's financial condition; evaluating and recording guarantees, collateral, and other security arrangements; negotiating lease terms and preparing and processing lease documents; and closing the transaction. The costs directly related to an employee's time spent on a specific lease transaction are also considered initial direct costs.

However, initial direct costs should not include internal indirect costs. Such costs are related to activities the lessor performs for advertising, servicing existing leases, and establishing and monitoring credit policies. Nor should the lessor include the costs for supervision and administration or for expenses such as rent and depreciation.

The accounting for initial direct costs depends on the type of lease:

For operating leases, the lessor should defer initial direct costs and allocate them over the lease term in proportion to the recognition of rental revenue.

For sales-type leases, the lessor expenses the initial direct costs in the period in which it recognizes the profit on the sale.

For a direct-financing lease, the lessor adds initial direct costs to the net investment in the lease and amortizes them over the life of the lease as a yield adjustment.

In a direct-financing lease, the lessor must disclose the unamortized deferred initial direct costs that are part of its investment in the direct-financing lease. For example, if the carrying value of the asset in the lease is $4,000,000 and the lessor incurs initial direct costs of $35,000, then the lease receivable (net investment in the lease) would be $4,035,000. The yield would be lower than the initial rate of return, and the lessor would adjust the yield to ensure proper amortization of the amount over the life of the lease.

Earlier in the chapter we presented the classification of the lease liability/receivable in an annuity-due situation. Illustration 21-7 (on page 1126) indicated that Sterling's current liability is the payment of $23,981.62 (excluding $2,000 of executory costs) to be made on January 1 of the next year. Similarly, as shown in Illustration 21-15 (on page 1134), Caterpillar's current asset is the $23,981.62 (excluding $2,000 of executory costs) it will collect on January 1 of the next year. In these annuity-due instances, the balance sheet date is December 31 and the due date of the lease payment is January 1 (less than one year), so the present value ($23,981.62) of the payment due the following January 1 is the same as the rental payment ($23,981.62).

What happens if the situation is an ordinary annuity rather than an annuity due? For example, assume that the rent is due at the end of the year (December 31) rather than at the beginning (January 1). FASB Statement No. 13 does not indicate how to measure the current and noncurrent amounts. It requires that for the lessee the "obligations shall be separately identified on the balance sheet as obligations under capital leases and shall be subject to the same considerations as other obligations in classifying them with current and noncurrent liabilities in classified balance sheets." [9] The most common method of measuring the current liability portion in ordinary annuity leases is the change-in-the-present-value method.[390]

To illustrate the change-in-the-present-value method, assume an ordinary-annuity situation with the same facts as the Caterpillar/Sterling case, excluding the $2,000 of executory costs. Because Sterling pays the rents at the end of the period instead of at the beginning, Caterpillar sets the five rents at $26,379.73, to have an effective interest rate of 10 percent. Illustration 21-30 shows the ordinary-annuity amortization schedule.

The current portion of the lease liability/receivable under the change-in-the-present-value method as of December 31, 2011, would be $18,017.70 ($83,620.27 − $65,602.57). As of December 31, 2012, the current portion would be $19,819.47 ($65,602.57 − $45,783.10). At December 31, 2011, Caterpillar classifies $65,602.57 of the receivable as noncurrent.

Thus, both the annuity-due and the ordinary-annuity situations report the reduction of principal for the next period as a current liability/current asset. In the annuity-due situation, Caterpillar accrues interest during the year but is not paid until the next period. As a result, a current asset arises for the receivable reduction and for the interest that was earned in the preceding period.

In the ordinary-annuity situation, the interest accrued during the period is also paid in the same period. Consequently, the lessor shows as a current asset only the principal reduction.

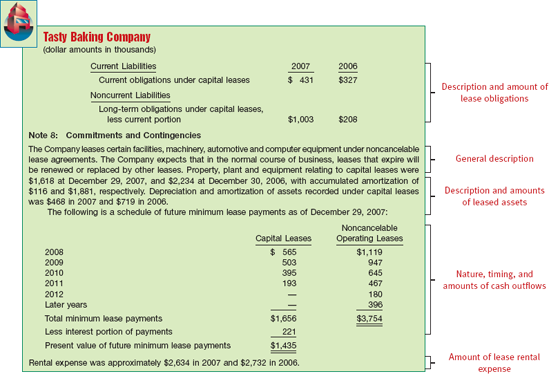

The FASB requires lessees and lessors to disclose certain information about leases in their financial statements or in the notes. These requirements vary based upon the type of lease (capital or operating) and whether the issuer is the lessor or lessee. These disclosure requirements provide investors with the following information:

General description of the nature of leasing arrangements.

The nature, timing, and amount of cash inflows and outflows associated with leases, including payments to be paid or received for each of the five succeeding years.

The amount of lease revenues and expenses reported in the income statement each period.

Description and amounts of leased assets by major balance sheet classification and related liabilities.

Amounts receivable and unearned revenues under lease agreements. [10]

Illustration 21-31 (on page 1147) presents financial statement excerpts from the 2007 annual report of Tasty Baking Company. These excerpts represent the statement and note disclosures typical of a lessee having both capital leases and operating leases.

Illustration 21-32 presents the lease note disclosure from the 2007 annual report of Hewlett-Packard Company. The disclosure highlights required lessor disclosures.

As we indicated at the beginning of this chapter, lease accounting is subject to abuse. Companies make strenuous efforts to circumvent GAAP in this area. In practice, the strong desires of lessees to resist capitalization have rendered the accounting rules for capitalizing leases partially ineffective. Leasing generally involves large dollar amounts that, when capitalized, materially increase reported liabilities and adversely affect the debt-to-equity ratio. Lessees also resist lease capitalization because charges to expense made in the early years of the lease term are higher under the capital lease method than under the operating method, frequently without tax benefit. As a consequence, "let's beat the lease standard" is one of the most popular games in town.[391]

To avoid leased asset capitalization, companies design, write, and interpret lease agreements to prevent satisfying any of the four capitalized lease criteria. Companies can easily devise lease agreements in such a way, by meeting the following specifications.

Ensure that the lease does not specify the transfer of title of the property to the lessee.

Do not write in a bargain-purchase option.

Set the lease term at something less than 75 percent of the estimated economic life of the leased property.

Arrange for the present value of the minimum lease payments to be less than 90 percent of the fair value of the leased property.

The real challenge lies in disqualifying the lease as a capital lease to the lessee, while having the same lease qualify as a capital (sales or financing) lease to the lessor. Unlike lessees, lessors try to avoid having lease arrangements classified as operating leases.[392]

Avoiding the first three criteria is relatively simple, but it takes a little ingenuity to avoid the "90 percent recovery test" for the lessee while satisfying it for the lessor. Two of the factors involved in this effort are: (1) the use of the incremental borrowing rate by the lessee when it is higher than the implicit interest rate of the lessor, by making information about the implicit rate unavailable to the lessee; and (2) residual value guarantees.

The lessee's use of the higher interest rate is probably the more popular subterfuge. Lessees are knowledgeable about the fair value of the leased property and, of course, the rental payments. However, they generally are unaware of the estimated residual value used by the lessor. Therefore, the lessee who does not know exactly the lessor's implicit interest rate might use a different (higher) incremental borrowing rate.

The residual value guarantee is the other unique, yet popular, device used by lessees and lessors. In fact, a whole new industry has emerged to circumvent symmetry between the lessee and the lessor in accounting for leases. The residual value guarantee has spawned numerous companies whose principal, or even sole, function is to guarantee the residual value of leased assets.

Because the minimum lease payments include the guaranteed residual value for the lessor, this satisfies the 90 percent recovery of fair market value test. The lease is a nonoperating lease to the lessor. But because a third-party guarantees the residual value, the minimum lease payments of the lessee exclude the guarantee. Thus, by merely transferring some of the risk to a third party, lessees can alter substantially the accounting treatment by converting what would otherwise be capital leases to operating leases.[393]

The nature of the criteria encourages much of this circumvention, stemming from weaknesses in the basic objective of the lease-accounting guidelines. Accounting rule-makers continue to have poor experience with arbitrary break points or other size and percentage criteria—such as rules like "90 percent of" and "75 percent of." Some believe that a more workable solution is to require capitalization of all leases that have noncancelable payment terms in excess of one year. Under this approach, lessee acquires an asset (a property right) and a corresponding liability, rather than on the basis that the lease transfers substantially all the risks and rewards of ownership.

Three years after it issued a lease-accounting pronouncement, a majority of the FASB expressed "the tentative view that, if the lease-accounting rules were to be reconsidered, they would support a property right approach in which all leases are included as 'rights to use property' and as 'lease obligations' in the lessee's balance sheet."[394] The FASB and other international standard-setters have issued a report on lease accounting that proposes the capitalization of more leases.[395]

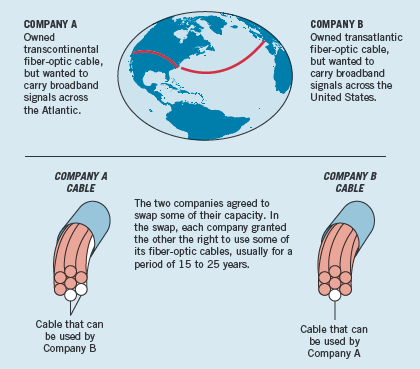

Telecommunication companies have developed one of the more innovative and controversial uses of leases. In order to provide fiber-optic service to their customers in areas where they did not have networks installed, telecommunication companies such as Global Crossing, Qwest Communications International, and Cable and Wireless entered into agreements to swap some of their unused network capacity in exchange for the use of another company's fiber-optic cables. Here's how it works:

Such trades seem like a good way to make efficient use of telecommunication assets. What got some telecommunications companies in trouble, though, was how they did the accounting for the swap.

The most conservative accounting for the capacity trades is to treat the swap as an exchange of assets, which does not affect the income statement. However, Global Crossing got into trouble with the SEC when it structured some of its capacity swaps as leases—the legal right to use capacity. Global Crossing was recognizing as revenue the payments received for the outgoing transfer of capacity, while payments for the incoming cable capacity were treated as capital expenditures, and therefore not expensed. As a result, Global Crossing was showing strong profits from its capacity swaps. However, the company's investors got an unpleasant surprise when the market for bandwidth cooled off and there was no longer demand for its broadband capacity or its long-term leasing arrangements.

Source: Simon Romero and Seth Schiesel, "The Fiber-Optic Fantasy Slips Away," New York Times on the Web (February 17, 2002). By permission.

Leasing is a global business. Lessors and lessees enter into arrangements with one another without regard to national boundaries. Although U.S. GAAP and iGAAP for leasing are similar, both the FASB and the IASB have decided that the existing accounting does not provide the most useful, transparent, and complete information about leasing transactions that should be provided in the financial statements.

Leasing was on the FASB's initial agenda in 1973 and SFAS No. 13 was issued in 1976 (before the conceptual framework was developed). SFAS No. 13 has been the subject of more than 30 interpretations since its issuance.

The iGAAP leasing standard is IAS 17, first issued in 1982. This standard is the subject of only three interpretations. One reason for this small number of interpretations is that iGAAP does not specifically address a number of leasing transactions that are covered by U.S. GAAP. Examples include lease agreements for natural resources, sale-leasebacks, real estate leases, and leveraged leases.

Both U.S. GAAP and iGAAP share the same objective of recording leases by lessees and lessors according to their economic substance—that is, according to the definitions of assets and liabilities.

U.S. GAAP for leases in much more "rule-based" with specific bright-line criteria to determine if a lease arrangement transfers the risks and rewards of ownership; iGAAP is more general in its provisions.

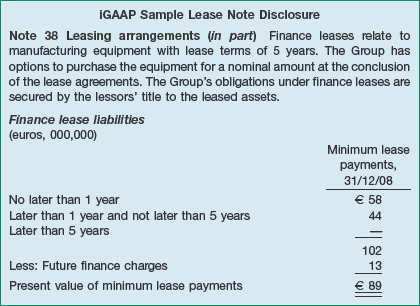

One illustration of the differences between U.S. GAAP and iGAAP for leases involves disclosure policy. Under U.S. GAAP, extensive disclosure of future noncancelable lease payments is required for the next five years and the years thereafter. Under iGAAP, not as much detail is required, as shown in the sample disclosure below.

Although some international companies (e.g., Nokia) provide a year-by-year breakout of payments due in years 1 through 5, iGAAP does not require it.

Lease accounting is one of the areas identified in the IASB/FASB Memorandum of Understanding and also a topic recommended by the SEC in its off-balance-sheet study for standard-setting attention. It was formally added to the agenda of the FASB and IASB as a joint project in 2006. The joint project will initially focus primarily on lessee accounting. One of the first areas to be studied is, "What are the assets and liabilities to be recognized related to a lease contract?" Should the focus remain on the leased item or the right to use the leased item? This question is tied to the Boards' joint project on the conceptual framework—defining an "asset" and a "liability."