LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

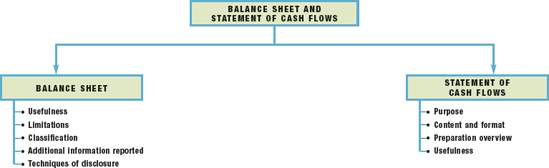

The balance sheet, sometimes referred to as the statement of financial position, reports the assets, liabilities, and stockholders' equity of a business enterprise at a specific date. This financial statement provides information about the nature and amounts of investments in enterprise resources, obligations to creditors, and the owners' equity in net resources.[60] It therefore helps in predicting the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of future cash flows.

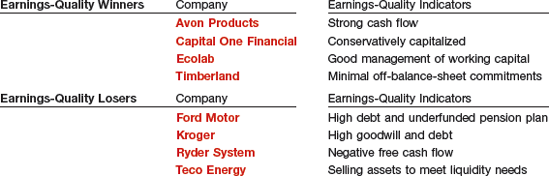

By providing information on assets, liabilities, and stockholders' equity, the balance sheet provides a basis for computing rates of return and evaluating the capital structure of the enterprise. As our opening story indicates, analysts also use information in the balance sheet to assess a company's risk[61] and future cash flows. In this regard, analysts use the balance sheet to assess a company's liquidity, solvency, and financial flexibility.

Liquidity describes "the amount of time that is expected to elapse until an asset is realized or otherwise converted into cash or until a liability has to be paid."[62] Creditors are interested in short-term liquidity ratios, such as the ratio of cash (or near cash) to short-term liabilities. These ratios indicate whether a company, like Amazon, will have the resources to pay its current and maturing obligations. Similarly, stockholders assess liquidity to evaluate the possibility of future cash dividends or the buyback of shares. In general, the greater Amazon's liquidity, the lower its risk of failure.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, showed how vulnerable the major airlines are to falling demand for their services. Since that infamous date, major airlines have reduced capacity and slashed jobs to avoid bankruptcy. United Airlines, Northwest Airlines, US Airways, and several smaller competitors filed for bankruptcy in the wake of 9/11.

Delta Airlines made the following statements in its annual report issued shortly after 9/11:

"If we are unsuccessful in further reducing our operating costs ... we will need to restructure our costs under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.... We have substantial liquidity needs and there is no assurance that we will be able to obtain the necessary financing to meet those needs on acceptable terms, if at all."

The financial distress related to the airline industry was not an insider's secret. The airlines' balance sheets clearly revealed their financial inflexibility and low liquidity even before September 11. For example, major airlines such as Braniff, Continental, Eastern, Midway, and America West declared bankruptcy before September 11.

These financial flexibility challenges have continued, exacerbated by ever-increasing fuel prices and labor costs. Not surprisingly, several of the major airlines (Delta, Northwest, Continental, United) have been exploring mergers as a way to build some competitive synergies and to bolster their financial flexibility.

Solvency refers to the ability of a company to pay its debts as they mature. For example, when a company carries a high level of long-term debt relative to assets, it has lower solvency than a similar company with a low level of long-term debt. Companies with higher debt are relatively more risky because they will need more of their assets to meet their fixed obligations (interest and principal payments).

Liquidity and solvency affect a company's financial flexibility, which measures the "ability of an enterprise to take effective actions to alter the amounts and timing of cash flows so it can respond to unexpected needs and opportunities."[63] For example, a company may become so loaded with debt—so financially inflexible—that it has little or no sources of cash to finance expansion or to pay off maturing debt. A company with a high degree of financial flexibility is better able to survive bad times, to recover from unexpected setbacks, and to take advantage of profitable and unexpected investment opportunities. Generally, the greater an enterprise's financial flexibility, the lower its risk of failure.

Some of the major limitations of the balance sheet are:

Most assets and liabilities are reported at historical cost. As a result, the information provided in the balance sheet is often criticized for not reporting a more relevant fair value. For example, Georgia-Pacific owns timber and other assets that may appreciate in value after purchase. Yet, Georgia-Pacific reports any increase only if and when it sells the assets.

Companies use judgments and estimates to determine many of the items reported in the balance sheet. For example, in its balance sheet, Dell estimates the amount of receivables that it will collect, the useful life of its warehouses, and the number of computers that will be returned under warranty.

The balance sheet necessarily omits many items that are of financial value but that a company cannot record objectively. For example, the knowledge and skill of Intel employees in developing new computer chips are arguably the company's most significant asset. However, because Intel cannot reliably measure the value of its employees and other intangible assets (such as customer base, research superiority, and reputation), it does not recognize these items in the balance sheet. Similarly, many liabilities are reported in an "off-balance-sheet" manner, if at all.

The recent bankruptcy of Enron, the seventh-largest U.S. company at the time, highlights the omission of important items in the balance sheet. In Enron's case, it failed to disclose certain off-balance-sheet financing obligations in its main financial statements.[64]

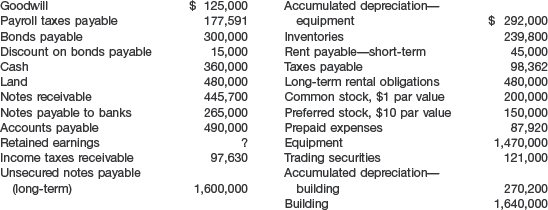

Balance sheet accounts are classified. That is, balance sheets group together similar items to arrive at significant subtotals. Furthermore, the material is arranged so that important relationships are shown.

The FASB has often noted that the parts and subsections of financial statements can be more informative than the whole. Therefore, the FASB discourages the reporting of summary accounts alone (total assets, net assets, total liabilities, etc.). Instead, companies should report and classify individual items in sufficient detail to permit users to assess the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of future cash flows. Such classification also makes it easier for users to evaluate the company's liquidity and financial flexibility, profitability, and risk.

To classify items in financial statements, companies group those items with similar characteristics and separate items with different characteristics.[65] For example, companies should report separately:

Assets that differ in their type or expected function in the company's central operations or other activities. For example, IBM reports merchandise inventories separately from property, plant, and equipment.

Assets and liabilities with different implications for the company's financial flexibility. For example, a company that uses assets in its operations, like Walgreens, should report those assets separately from assets held for investment and assets subject to restrictions, such as leased equipment.

Assets and liabilities with different general liquidity characteristics. For example, Boeing Company reports cash separately from inventories.

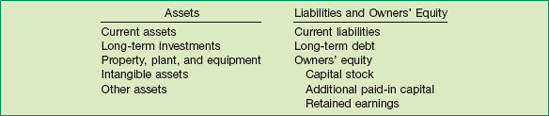

The three general classes of items included in the balance sheet are assets, liabilities, and equity. We defined them in Chapter 2 as follows.

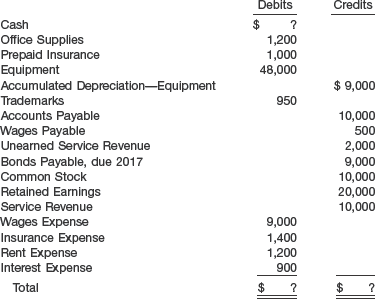

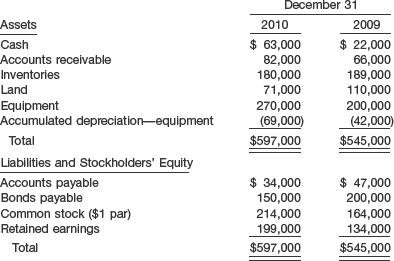

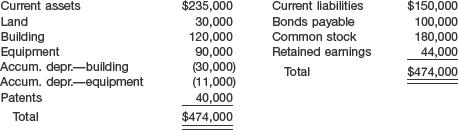

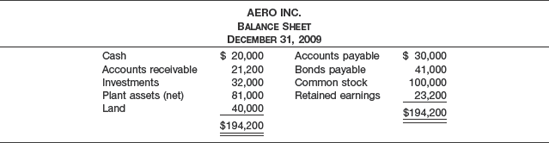

Companies then further divide these items into several subclassifications. Illustration 5-1 indicates the general format of balance sheet presentation.

A company may classify the balance sheet in some other manner, but in practice you usually see little departure from these major subdivisions. A proprietorship or partnership does present the classifications within the owners' equity section a little differently, as we will show later in the chapter.

Current assets are cash and other assets a company expects to convert into cash, sell, or consume either in one year or in the operating cycle, whichever is longer. The operating cycle is the average time between when a company acquires materials and supplies and when it receives cash for sales of the product (for which it acquired the materials and supplies). The cycle operates from cash through inventory, production, receivables, and back to cash. When several operating cycles occur within one year (which is generally the case for service companies), a company uses the one-year period. If the operating cycle is more than one year, a company uses the longer period.

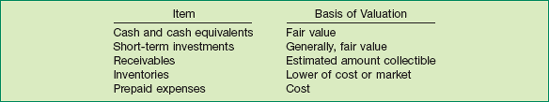

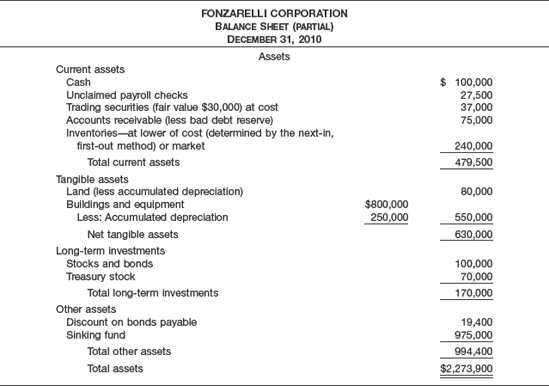

Current assets are presented in the balance sheet in order of liquidity. The five major items found in the current assets section, and their bases of valuation, are shown in Illustration 5-2.

A company does not report these five items as current assets if it does not expect to realize them in one year or in the operating cycle, whichever is longer. For example, a company excludes from the current assets section cash restricted for purposes other than payment of current obligations or for use in current operations. Generally, if a company expects to convert an asset into cash or to use it to pay a current liability within a year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer, it classifies the asset as current.

This rule, however, is subject to interpretation. A company classifies an investment in common stock as either a current asset or a noncurrent asset depending on management's intent. When it has small holdings of common stocks or bonds that it will hold long-term, it should not classify them as current.

Although a current asset is well defined, certain theoretical problems also develop. For example, how is including prepaid expenses in the current assets section justified? The rationale is that if a company did not pay these items in advance, it would instead need to use other current assets during the operating cycle. If we follow this logic to its ultimate conclusion, however, any asset previously purchased saves the use of current assets during the operating cycle and would be considered current.

Another problem occurs in the current-asset definition when a company consumes plant assets during the operating cycle. Conceptually, it seems that a company should place in the current assets section an amount equal to the current depreciation charge on the plant assets, because it will consume them in the next operating cycle. However, this conceptual problem is ignored. This example illustrates that the formal distinction made between some current and noncurrent assets is somewhat arbitrary.

Cash is generally considered to consist of currency and demand deposits (monies available on demand at a financial institution). Cash equivalents are short-term highly liquid investments that will mature within three months or less. Most companies use the caption "Cash and cash equivalents," and they indicate that this amount approximates fair value.

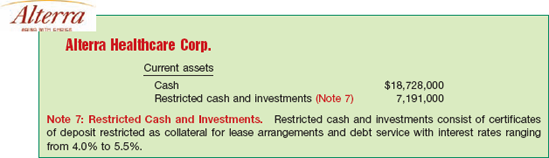

A company must disclose any restrictions or commitments related to the availability of cash. As an example, see the excerpt from the annual report of Alterra Healthcare Corp. in Illustration 5-3 on the next page.

Alterra Healthcare restricted cash to meet an obligation due currently. Therefore, Alterra included this restricted cash under current assets.

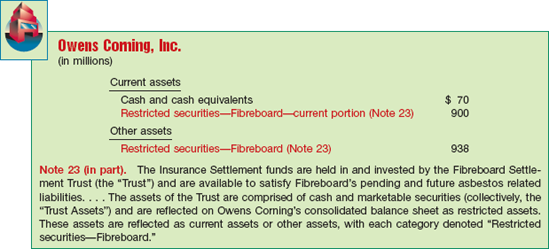

If a company restricts cash for purposes other than current obligations, it excludes the cash from current assets. Illustration 5-4 shows an example of this, from the annual report of Owens Corning, Inc.

Companies group investments in debt and equity securities into three separate portfolios for valuation and reporting purposes:

Held-to-maturity: Debt securities that a company has the positive intent and ability to hold to maturity.

Trading: Debt and equity securities bought and held primarily for sale in the near term to generate income on short-term price differences.

Available-for-sale: Debt and equity securities not classified as held-to-maturity or trading securities.

A company should report trading securities (whether debt or equity) as current assets. It classifies individual held-to-maturity and available-for-sale securities as current or noncurrent depending on the circumstances. It should report held-to-maturity securities at amortized cost. All trading and available-for-sale securities are reported at fair value. [1][67]

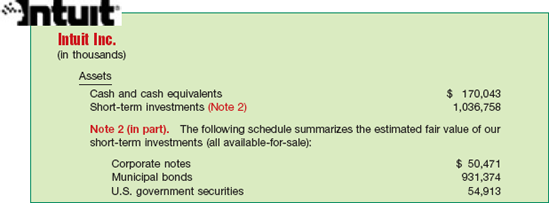

For example, see Illustration 5-5 on the next page, which is an excerpt from the annual report of Intuit Inc. with respect to its available-for-sale investments.

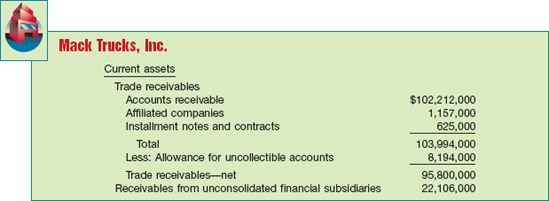

A company should clearly identify any anticipated loss due to uncollectibles, the amount and nature of any nontrade receivables, and any receivables used as collateral. Major categories of receivables should be shown in the balance sheet or the related notes. For receivables arising from unusual transactions (such as sale of property, or a loan to affiliates or employees), companies should separately classify these as long-term, unless collection is expected within one year. Mack Trucks, Inc. reported its receivables as shown in Illustration 5-6.

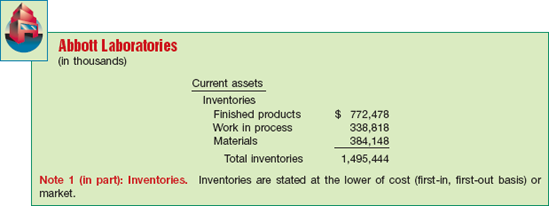

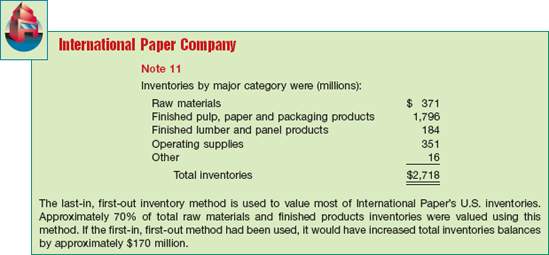

To present inventories properly, a company discloses the basis of valuation (e.g., lower-of-cost-or-market) and the cost flow assumption used (e.g., FIFO or LIFO). A manufacturing concern (like Abbott Laboratories, shown in Illustration 5-7) also indicates the stage of completion of the inventories.

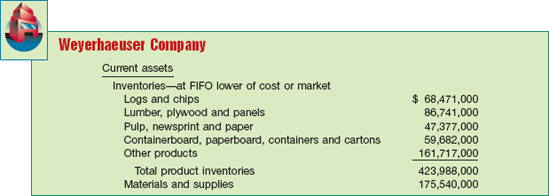

Weyerhaeuser Company, a forestry company and lumber manufacturer with several finished-goods product lines, reported its inventory as shown in Illustration 5-8.

A company includes prepaid expenses in current assets if it will receive benefits (usually services) within one year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer.[68] As we discussed earlier, these items are current assets because if they had not already been paid, they would require the use of cash during the next year or the operating cycle. A company reports prepaid expenses at the amount of the unexpired or unconsumed cost.

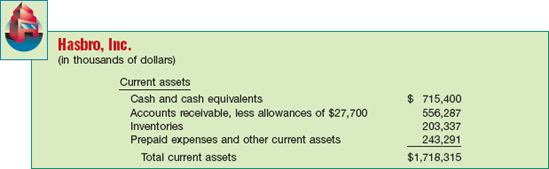

A common example is the prepayment for an insurance policy. A company classifies it as a prepaid expense because the payment precedes the receipt of the benefit of coverage. Other common prepaid expenses include prepaid rent, advertising, taxes, and office or operating supplies. Hasbro, Inc., for example, listed its prepaid expenses in current assets as shown in Illustration 5-9.

Noncurrent assets are those not meeting the definition of current assets. They include a variety of items, as we discuss in the following sections.

Long-term investments, often referred to simply as investments, normally consist of one of four types:

Investments in securities, such as bonds, common stock, or long-term notes.

Investments in tangible fixed assets not currently used in operations, such as land held for speculation.

Investments set aside in special funds such as a sinking fund, pension fund, or plant expansion fund. This includes the cash surrender value of life insurance.

Investments in nonconsolidated subsidiaries or affiliated companies.

Companies expect to hold long-term investments for many years. They usually present them on the balance sheet just below "Current assets," in a separate section called "Investments." Realize that many securities classified as long-term investments are, in fact, readily marketable. But a company does not include them as current assets unless it intends to convert them to cash in the short-term—that is, within a year or in the operating cycle, whichever is longer. As indicated earlier, securities classified as available-for-sale are reported at fair value, and held-to-maturity securities are reported at amortized cost.

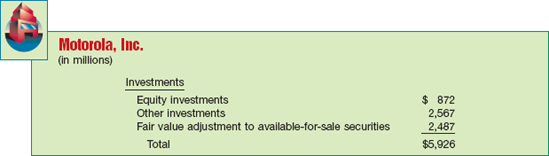

Motorola, Inc. reported its investments section, located between "Property, plant, and equipment" and "Other assets," as shown in Illustration 5-10.

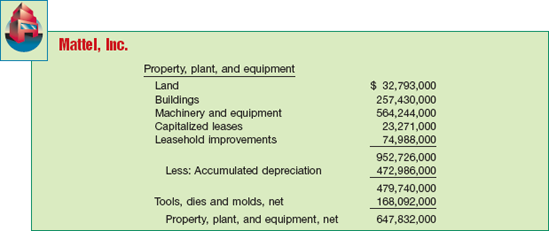

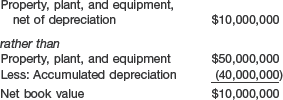

Property, plant, and equipment are tangible long-lived assets used in the regular operations of the business. These assets consist of physical property such as land, buildings, machinery, furniture, tools, and wasting resources (timberland, minerals). With the exception of land, a company either depreciates (e.g., buildings) or depletes (e.g., timberlands or oil reserves) these assets.

Mattel, Inc. presented its property, plant, and equipment in its balance sheet as shown in Illustration 5-11.

A company discloses the basis it uses to value property, plant, and equipment; any liens against the properties; and accumulated depreciation—usually in the notes to the statements.

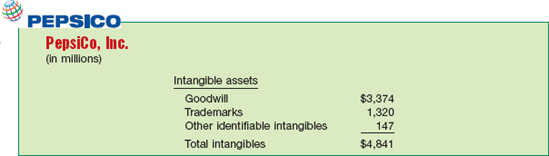

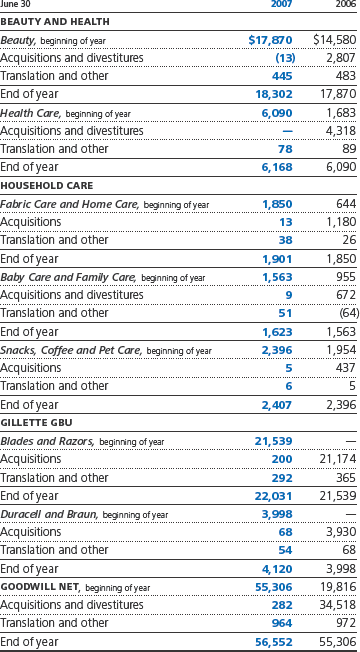

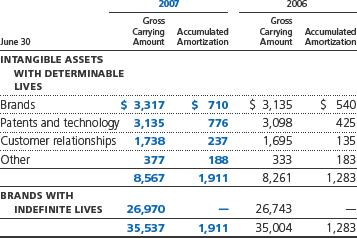

Intangible assets lack physical substance and are not financial instruments (see definition on page 193). They include patents, copyrights, franchises, goodwill, trademarks, trade names, and customer lists. A company writes off (amortizes) limited-life intangible assets over their useful lives. It periodically assesses indefinite-life intangibles (such as goodwill) for impairment. Intangibles can represent significant economic resources, yet financial analysts often ignore them, because valuation is difficult.

PepsiCo, Inc. reported intangible assets in its balance sheet as shown in Illustration 5-12.

The items included in the section "Other assets" vary widely in practice. Some include items such as long-term prepaid expenses, prepaid pension cost, and noncurrent receivables. Other items that might be included are assets in special funds, deferred income taxes, property held for sale, and restricted cash or securities. A company should limit this section to include only unusual items sufficiently different from assets included in specific categories.

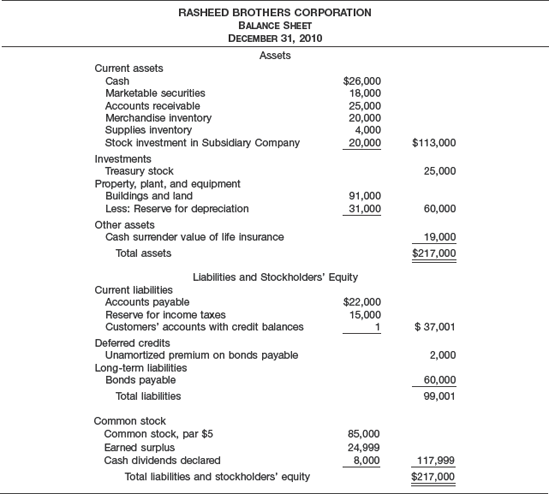

Similar to assets, companies classify liabilities as current or long-term.

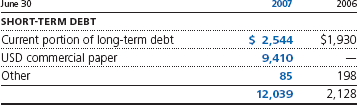

Current liabilities are the obligations that a company reasonably expects to liquidate either through the use of current assets or the creation of other current liabilities. This concept includes:

Payables resulting from the acquisition of goods and services: accounts payable, wages payable, taxes payable, and so on.

Collections received in advance for the delivery of goods or performance of services, such as unearned rent revenue or unearned subscriptions revenue.

Other liabilities whose liquidation will take place within the operating cycle, such as the portion of long-term bonds to be paid in the current period or short-term obligations arising from purchase of equipment.

At times, a liability that is payable within the next year is not included in the current liabilities section. This occurs either when the company expects to refinance the debt through another long-term issue [3] or to retire the debt out of noncurrent assets. This approach is used because liquidation does not result from the use of current assets or the creation of other current liabilities.

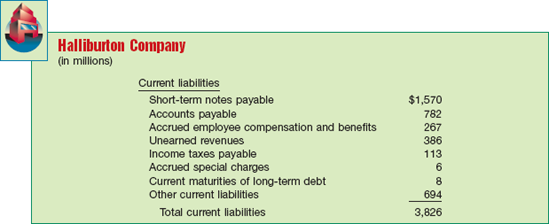

Companies do not report current liabilities in any consistent order. In general, though, companies most commonly list notes payable, accounts payable, or short-term debt as the first item. Income taxes payable, current maturities of long-term debt, or other current liabilities are commonly listed last. For example, see Halliburton Company's current liabilities section in Illustration 5-13 on the next page.

Current liabilities include such items as trade and nontrade notes and accounts payable, advances received from customers, and current maturities of long-term debt. If the amounts are material, companies classify income taxes and other accrued items separately. A company should fully describe in the notes any information about a secured liability—for example, stock held as collateral on notes payable—to identify the assets providing the security.

The excess of total current assets over total current liabilities is referred to as working capital (or sometimes net working capital). Working capital represents the net amount of a company's relatively liquid resources. That is, it is the liquidity buffer available to meet the financial demands of the operating cycle.

Companies seldom disclose on the balance sheet an amount for working capital. But bankers and other creditors compute it as an indicator of the short-run liquidity of a company. To determine the actual liquidity and availability of working capital to meet current obligations, however, requires analysis of the composition of the current assets and their nearness to cash.

Before the dot-com bubble burst, concerns about liquidity and solvency led creditors of many dotcom companies to demand more assurances that these companies could pay their bills when due. A key indicator for creditors is the amount of working capital. For example, when a report predicted that Amazon.com's working capital would turn negative, the company's vendors began to explore steps that would ensure that Amazon would pay them.

Some vendors demanded that their dot-com customers sign notes stating that the goods shipped to them would serve as collateral for the transaction. Other vendors began shipping goods on consignment—an arrangement whereby the vendor retains ownership of the goods until a third party buys and pays for them.

Another recent bubble in the real estate market created a working capital and liquidity crisis for no less a revered financial institution than Bear Stearns. What happened? Bear Stearns was one of the biggest investors in mortgage-backed securities. But when the housing market cooled off and the value of the collateral backing Bear Stearns's mortgage securities dropped dramatically, the market began to question Bear's ability to meet its obligations. The result: The Federal Reserve stepped in to avert a collapse of the company, backing a bailout plan that guaranteed $30 billion of Bear Stearns's investments. This paved the way for a buy-out by J.P. Morgan Chase at $2 per share (later amended to $10 a share)—quite a bargain since Bear Stearns had been trading above $80 a share just a month earlier.

Source: Robin Sidel, Greg Ip, Michael M. Phillips, and Kate Kelly, "The Week That Shook Wall Street: Inside the Demise of Bear Stearns," Wall Street Journal (March 18, 2008), p. A1.

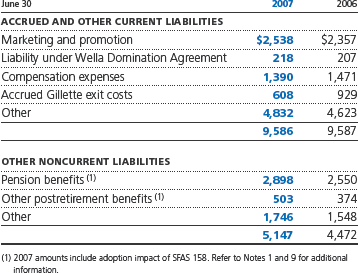

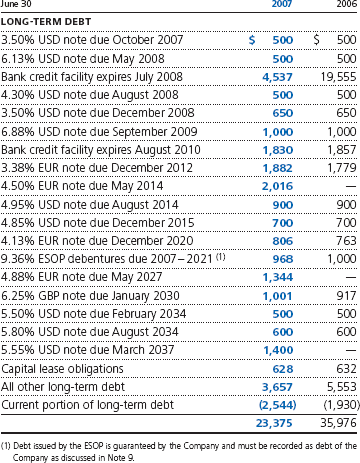

Long-term liabilities are obligations that a company does not reasonably expect to liquidate within the normal operating cycle. Instead, it expects to pay them at some date beyond that time. The most common examples are bonds payable, notes payable, some deferred income tax amounts, lease obligations, and pension obligations. Companies classify long-term liabilities that mature within the current operating cycle as current liabilities if payment of the obligation requires the use of current assets.

Generally, long-term liabilities are of three types:

Obligations arising from specific financing situations, such as the issuance of bonds, long-term lease obligations, and long-term notes payable.

Obligations arising from the ordinary operations of the company, such as pension obligations and deferred income tax liabilities.

Obligations that depend on the occurrence or non-occurrence of one or more future events to confirm the amount payable, or the payee, or the date payable, such as service or product warranties and other contingencies.

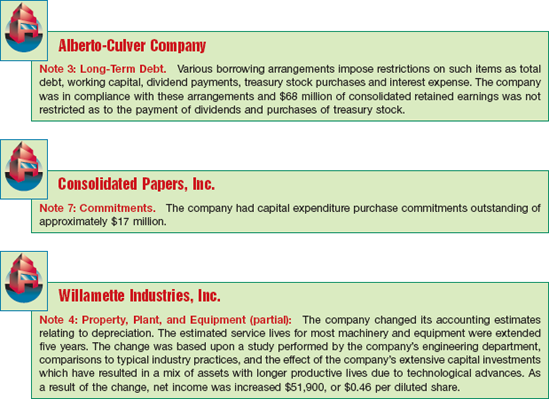

Companies generally provide a great deal of supplementary disclosure for long-term liabilities, because most long-term debt is subject to various covenants and restrictions for the protection of lenders.[69]

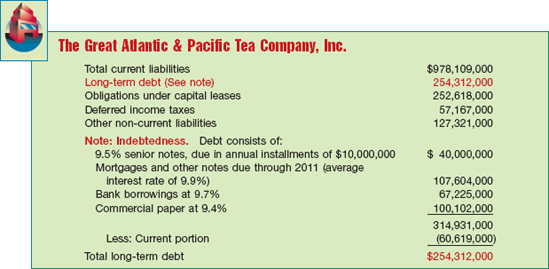

It is desirable to report any premium or discount separately as an addition to or subtraction from the bonds payable. Companies frequently describe the terms of all long-term liability agreements (including maturity date or dates, rates of interest, nature of obligation, and any security pledged to support the debt) in notes to the financial statements. Illustration 5-14 provides an example of this, taken from an excerpt from The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company's financials.

The owners' equity (stockholders' equity) section is one of the most difficult sections to prepare and understand. This is due to the complexity of capital stock agreements and the various restrictions on stockholders' equity imposed by state corporation laws, liability agreements, and boards of directors. Companies usually divide the section into three parts:

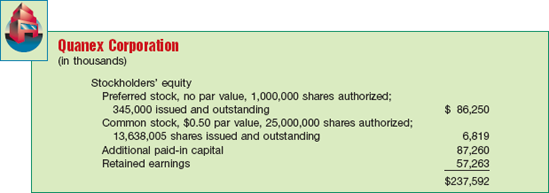

For capital stock, companies must disclose the par value and the authorized, issued, and outstanding share amounts. A company usually presents the additional paid-in capital in one amount, although subtotals are informative if the sources of additional capital are varied and material. The retained earnings amount may be divided between the unappropriated (the amount that is usually available for dividend distribution) and restricted (e.g., by bond indentures or other loan agreements) amounts. In addition, companies show any capital stock reacquired (treasury stock) as a reduction of stockholders' equity.

Illustration 5-15 presents an example of the stockholders' equity section from Quanex Corporation.

The ownership or stockholders' equity accounts in a corporation differ considerably from those in a partnership or proprietorship. Partners show separately their permanent capital accounts and the balance in their temporary accounts (drawing accounts). Proprietorships ordinarily use a single capital account that handles all of the owner's equity transactions.

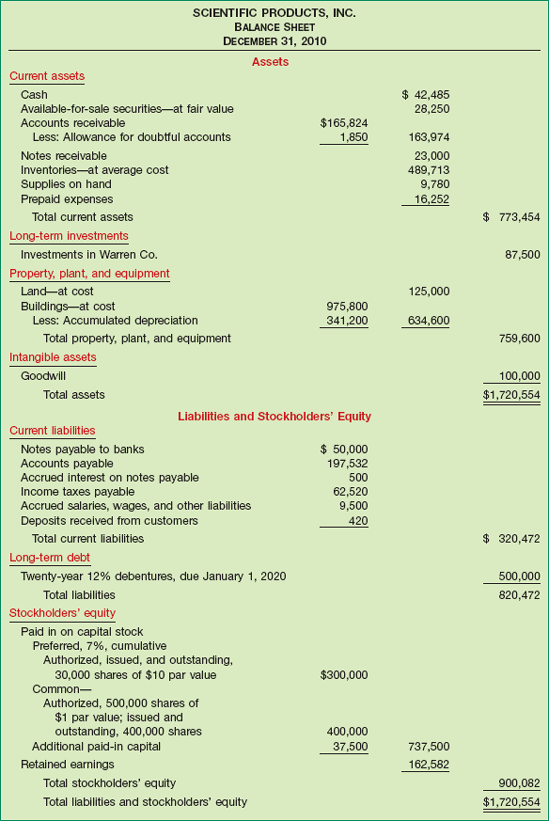

One common arrangement that companies use in presenting a classified balance sheet is the account form. It lists assets, by sections, on the left side, and liabilities and stockholders' equity, by sections, on the right side. The main disadvantage is the need for a sufficiently wide space in which to present the items side by side. Often, the account form requires two facing pages.

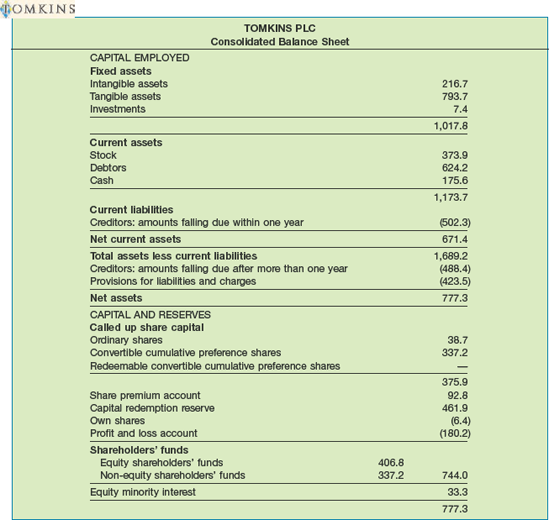

To avoid this disadvantage, the report form lists the sections one above the other, on the same page. See, for example, Illustration 5-16, which lists assets, followed by liabilities and stockholders' equity directly below, on the same page.[70]

Infrequently, companies use other balance sheet formats. For example, companies sometimes deduct current liabilities from current assets to arrive at working capital. Or, they deduct all liabilities from all assets.

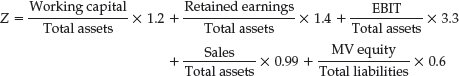

Analysts use balance sheet information in models designed to predict financial distress. Researcher E. I. Altman pioneered a bankruptcy-prediction model that derives a "Z-score" by combining balance sheet and income measures in the following equation.

Following extensive testing, Altman found that companies with Z-scores above 3.0 are unlikely to fail. Those with Z-scores below 1.81 are very likely to fail.

Altman developed the original model for publicly held manufacturing companies. He and others have modified the model to apply to companies in various industries, emerging companies, and companies not traded in public markets.

At one time, the use of Z-scores was virtually unheard of among practicing accountants. Today, auditors, management consultants, and courts of law use this measure to help evaluate the overall financial position and trends of a firm. In addition, banks use Z-scores for loan evaluation. While a low score does not guarantee bankruptcy, the model has been proven accurate in many situations.

Source: Adapted from E. I. Altman and E. Hotchkiss, Corporate Financial Distress and Bankruptcy, 3rd edition (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2005).

The balance sheet is not complete if a company simply lists the assets, liabilities, and owners' equity accounts. It still needs to provide important supplemental information. This may be information not presented elsewhere in the statement, or it may elaborate on items in the balance sheet. There are normally four types of information that are supplemental to account titles and amounts presented in the balance sheet. They are listed below.

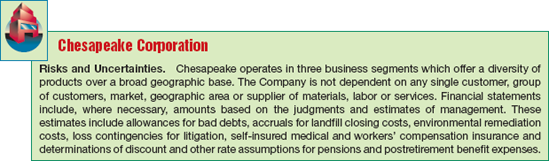

A contingency is an existing situation involving uncertainty as to possible gain (gain contingency) or loss (loss contingency) that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur. In short, contingencies are material events with an uncertain future. Examples of gain contingencies are tax operating-loss carryforwards or company litigation against another party. Typical loss contingencies relate to litigation, environmental issues, possible tax assessments, or government investigations. We examine the accounting and reporting requirements involving contingencies more fully in Chapter 13.

GAAP recommends disclosure for all significant accounting principles and methods that involve selection from among alternatives or those that are peculiar to a given industry. [5] For instance, companies can compute inventories under several cost flow assumptions (e.g., LIFO and FIFO), depreciate plant and equipment under several accepted methods (e.g., double-declining balance and straight-line), and carry investments at different valuations (e.g., cost, equity, and fair value). Sophisticated users of financial statements know of these possibilities and examine the statements closely to determine the methods used.

Companies must also disclose information about the nature of their operations, the use of estimates in preparing financial statements, certain significant estimates, and vulnerabilities due to certain concentrations. [6] Illustration 5-17 shows an example of such a disclosure.

Disclosure of significant accounting principles and methods and of risks and uncertainties is particularly useful if given in a separate Summary of Significant Accounting Policies preceding the notes to the financial statements or as the initial note.

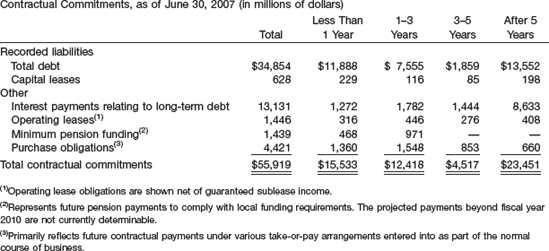

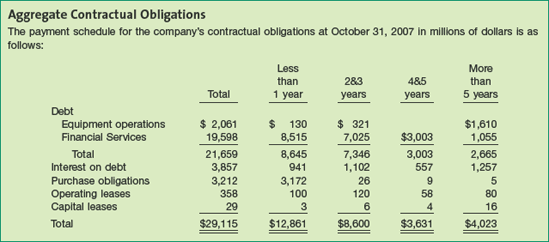

Companies should disclose contractual situations, if significant, in the notes to the financial statements. For example, they must clearly state the essential provisions of lease contracts, pension obligations, and stock option plans in the notes. Analysts want to know not only the amount of the liabilities, but also how the different contractual provisions affect the company at present and in the future.

Companies must disclose the following commitments if the amounts are material: commitments related to obligations to maintain working capital, to limit the payment of dividends, to restrict the use of assets, and to require the maintenance of certain financial ratios. Management must exercise considerable judgment to determine whether omission of such information is misleading. The rule in this situation is, "When in doubt, disclose." It is better to disclose a little too much information than not enough.

Many of the recent accounting scandals related to the nondisclosure of significant contractual obligations. In response, the SEC has mandated that companies disclose contractual obligations in a tabular summary in the management discussion and analysis section of the company's annual report.

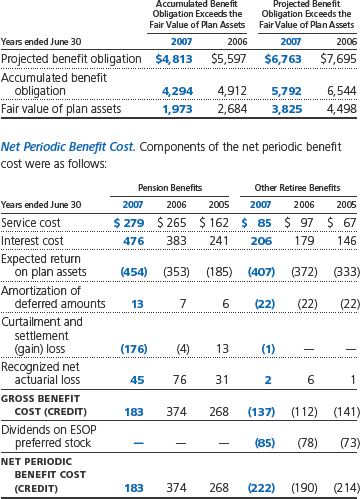

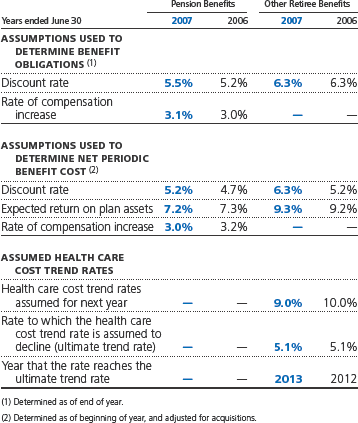

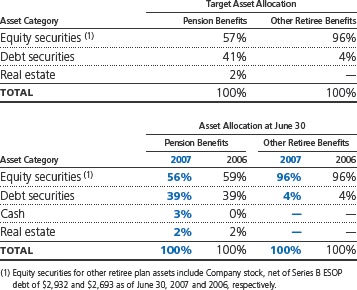

Presented below, as an example, is a disclosure from The Procter & Gamble Company.

As we have discussed, fair value information may be more useful than historical cost for certain types of assets and liabilities. This is particularly so in the case of financial instruments. Financial instruments are defined as cash, an ownership interest, or a contractual right to receive or obligation to deliver cash or another financial instrument. Such contractual rights to receive cash or other financial instruments are assets. Contractual obligations to pay are liabilities. Cash, investments, accounts receivable, and payables are examples of financial instruments.

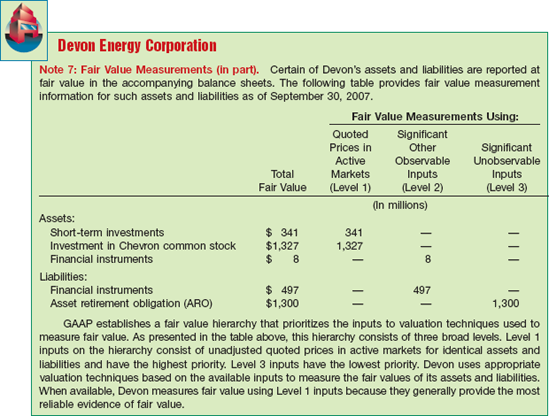

Given the expanded use of fair value measurements, as discussed in Chapter 2, GAAP also has expanded disclosures about fair value measurements. [7] To increase consistency and comparability in the use of fair value measures, companies follow a fair value hierarchy that provides insight into how to determine fair value. The hierarchy has three levels. Level 1 measures (the most reliable) are based on observable inputs, such as market prices for identical assets or liabilities. Level 2 measures (less reliable) are based on market-based inputs other than those included in Level 1, such as those based on market prices for similar assets or liabilities. Level 3 measures (least reliable) are based on unobservable inputs, such as a company's own data or assumptions.[71]

For major groups of assets and liabilities, companies must make the following fair value disclosures: (1) the fair value measurement and (2) the fair value hierarchy level of the measurements as a whole, classified by Level 1, 2, or 3. Illustration 5-18 (page 194) provides a disclosure for Devon Energy for its assets and liabilities measured at fair value.

In addition, companies must provide significant additional disclosure related to Level 3 measurements. The disclosures related to Level 3 are substantial and must identify what assumptions the company used to generate the fair value numbers and any related income effects. Companies will want to use Level 1 and 2 measurements as much as possible. In most cases, these valuations should be very reliable, as the fair value measurements are based on market information. In contrast, a company that uses Level 3 measurements extensively must be carefully evaluated to understand the impact these valuations have on the financial statements.

Companies should disclose as completely as possible the effect of various contingencies on financial condition, the methods of valuing assets and liabilities, and the company's contracts and agreements. To disclose this pertinent information, companies may use parenthetical explanations, notes, cross reference and contra items, and supporting schedules.

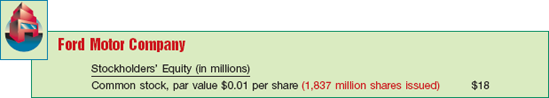

Companies often provide additional information by parenthetical explanations following the item. For example, Illustration 5-19 shows a parenthetical explanation of the number of shares issued by Ford Motor Company on the balance sheet under "Stockholders' equity."

This additional pertinent balance sheet information adds clarity and completeness. It has an advantage over a note because it brings the additional information into the body of the statement where readers will less likely overlook it. Companies, however, should avoid lengthy parenthetical explanations, which might be distracting.

Companies use notes if they cannot conveniently show additional explanations as parenthetical explanations. Illustration 5-20 shows how International Paper Company reported its inventory costing methods in its accompanying notes.

Companies commonly use notes to disclose the following: the existence and amount of any preferred stock dividends in arrears, the terms of or obligations imposed by purchase commitments, special financial arrangements and instruments, depreciation policies, any changes in the application of accounting principles, and the existence of contingencies.

Notes therefore must present all essential facts as completely and succinctly as possible. Careless wording may mislead rather than aid readers. Notes should add to the total information made available in the financial statements, not raise unanswered questions or contradict other portions of the statements. The following notes illustrate the presentation of such information.

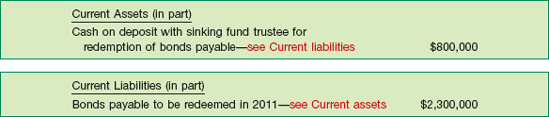

Companies "cross-reference" a direct relationship between an asset and a liability on the balance sheet. For example, as shown in Illustration 5-22, on December 31, 2010, a company might show the following entries—one listed among the current assets, and the other listed among the current liabilities.

This cross-reference points out that the company will redeem $2,300,000 of bonds payable currently, for which it has only set aside $800,000. Therefore, it needs additional cash from unrestricted cash, from sales of investments, from profits, or from some other source. Alternatively, the company can show the same information parenthetically.

Another common procedure is to establish contra or adjunct accounts. A contra account on a balance sheet reduces either an asset, liability, or owners' equity account. Examples include Accumulated Depreciation and Discount on Bonds Payable. Contra accounts provide some flexibility in presenting the financial information. With the use of the Accumulated Depreciation account, for example, a reader of the statement can see the original cost of the asset as well as the depreciation to date.

An adjunct account, on the other hand, increases either an asset, liability, or owners' equity account. An example is Premium on Bonds Payable, which, when added to the Bonds Payable account, describes the total bond liability of the company.

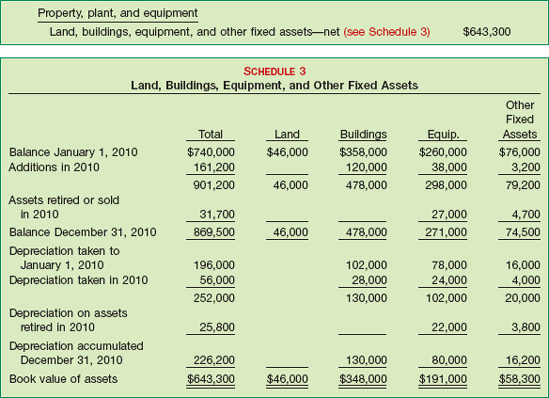

Often a company needs a separate schedule to present more detailed information about certain assets or liabilities, as follows.

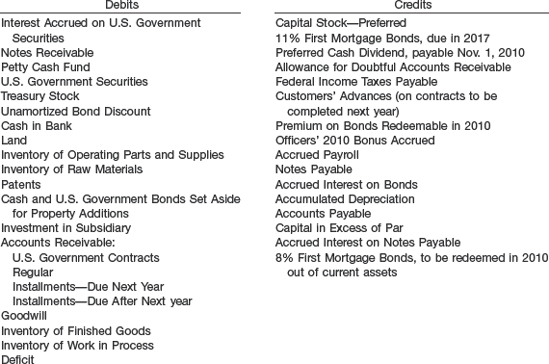

The account titles in the general ledger do not necessarily represent the best terminology for balance sheet purposes. Companies often use brief account titles and include technical terms that only accountants understand. But many persons unacquainted with accounting terminology examine balance sheets. Thus, balance sheets should contain descriptions that readers will generally understand and clearly interpret.

For example, companies have used the term "reserve" in differing ways: to describe amounts deducted from assets (contra accounts such as accumulated depreciation and allowance for doubtful accounts); as a part of the title of contingent or estimated liabilities; and to describe an appropriation of retained earnings. Because of the different meanings attached to this term, misinterpretation often resulted from its use. Therefore, the profession has recommended that companies use the word reserve only to describe an appropriation of retained earnings. The use of the term in this narrower sense—to describe appropriated retained earnings—has resulted in a better understanding of its significance when it appears in a balance sheet. However, the term "appropriated" appears more logical, and we encourage its use.

For years the profession has recommended that the use of the word surplus be discontinued in balance sheet presentations of owners' equity. The use of the terms capital surplus, paid-in surplus, and earned surplus is confusing. Although condemned by the profession, these terms appear all too frequently in current financial statements.

Chapter 2 indicated that one of the three basic objectives of financial reporting is "assessing the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of cash flows." The three financial statements we have looked at so far—the income statement, the statement of stockholders' equity, and the balance sheet—each present some information about the cash flows of an enterprise during a period. But they do so to a limited extent. For instance, the income statement provides information about resources provided by operations, but not exactly cash. The statement of stockholders' equity shows the amount of cash used to pay dividends or purchase treasury stock. Comparative balance sheets might show what assets the company has acquired or disposed of and what liabilities it has incurred or liquidated.

Useful as they are, none of these statements presents a detailed summary of all the cash inflows and outflows, or the sources and uses of cash during the period. To fill this need, the FASB requires the statement of cash flows (also called the cash flow statement). [8]

The primary purpose of a statement of cash flows is to provide relevant information about the cash receipts and cash payments of an enterprise during a period. To achieve this purpose, the statement of cash flows reports the following: (1) the cash effects of operations during a period, (2) investing transactions, (3) financing transactions, and (4) the net increase or decrease in cash during the period.[72]

Reporting the sources, uses, and net increase or decrease in cash helps investors, creditors, and others know what is happening to a company's most liquid resource. Because most individuals maintain a checkbook and prepare a tax return on a cash basis, they can comprehend the information reported in the statement of cash flows.

The statement of cash flows provides answers to the following simple but important questions:

Where did the cash come from during the period?

What was the cash used for during the period?

What was the change in the cash balance during the period?

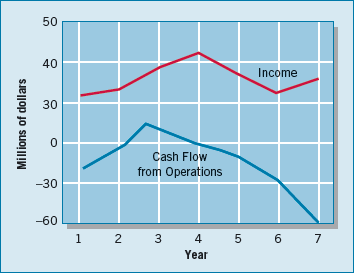

Investors usually focus on net income measured on an accrual basis. However, information on cash flows can be important for assessing a company's liquidity, financial flexibility, and overall financial performance. The graph below shows W. T. Grant's financial performance over 7 years.

Although W. T. Grant showed consistent profits and even some periods of earnings growth, its cash flow began to "go south" starting in about year 3. The company filed for bankruptcy shortly after year 7. Financial statement readers who studied the company's cash flows would have found early warnings of W. T. Grant's problems. The Grant experience is a classic case, illustrating the importance of cash flows as an early-warning signal of financial problems.

A more recent retailer case is Target. Although Target has shown good profits, some are concerned that a bit too much of its sales have been made on credit rather than cash. Why is this a problem? Like W. T. Grant, the earnings of profitable lenders can get battered in future periods if they have to start adding large amounts to their bad-loan reserve to catch up with credit losses. And if losses ramp up on Target-branded credit cards, Target may get hit in this way.

Source: Peter Eavis, "Is Target Corp.'s Credit Too Generous?" Wall Street Journal (March 11, 2008), p. C1.

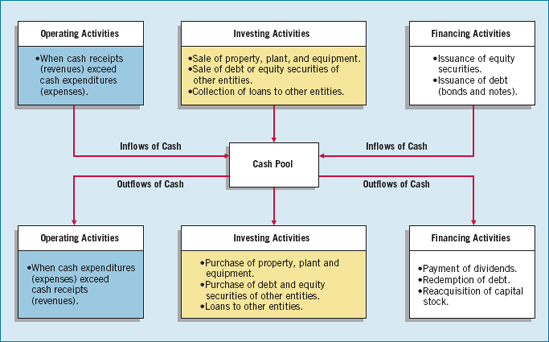

Companies classify cash receipts and cash payments during a period into three different activities in the statement of cash flows—operating, investing, and financing activities, defined as follows.

Operating activities involve the cash effects of transactions that enter into the determination of net income.

Investing activities include making and collecting loans and acquiring and disposing of investments (both debt and equity) and property, plant, and equipment.

Financing activities involve liability and owners' equity items. They include (a) obtaining resources from owners and providing them with a return on their investment, and (b) borrowing money from creditors and repaying the amounts borrowed.

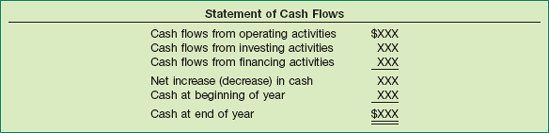

Illustration 5-24 shows the basic format of the statement of cash flows.

Illustration 5-25 graphs the inflows and outflows of cash classified by activity.

The statement's value is that it helps users evaluate liquidity, solvency, and financial flexibility. As stated earlier, liquidity refers to the "nearness to cash" of assets and liabilities. Solvency is the firm's ability to pay its debts as they mature. Financial flexibility is a company's ability to respond and adapt to financial adversity and unexpected needs and opportunities.

We have devoted Chapter 23 entirely to the detailed preparation and content of the statement of cash flows. The intervening chapters will cover several elements and complex topics that affect the content of a typical statement of cash flows. The presentation in this chapter is introductory—a reminder of the existence of the statement of cash flows and its usefulness.

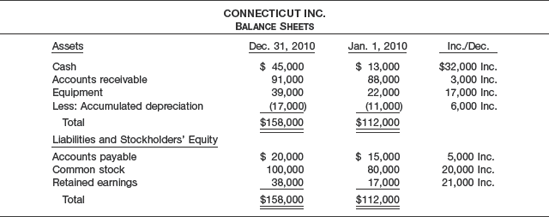

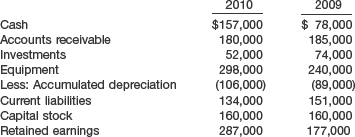

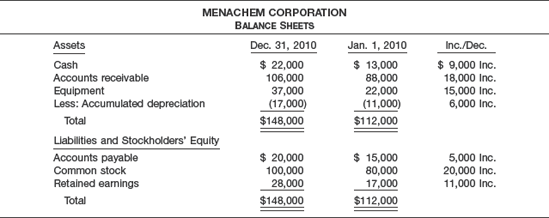

Companies obtain the information to prepare the statement of cash flows from several sources: (1) comparative balance sheets, (2) the current income statement, and (3) selected transaction data.

The following simple example demonstrates how companies use these sources in preparing a statement of cash flows.

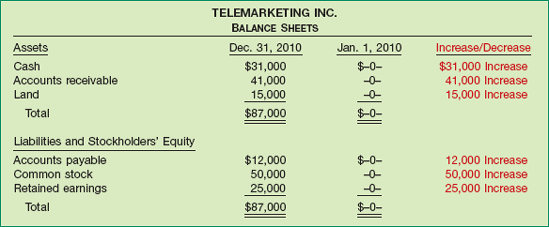

On January 1, 2010, in its first year of operations, Telemarketing Inc. issued 50,000 shares of $1 par value common stock for $50,000 cash. The company rented its office space, furniture, and telecommunications equipment and performed marketing services throughout the first year. In June 2010 the company purchased land for $15,000. Illustration 5-26 shows the company's comparative balance sheets at the beginning and end of 2010.

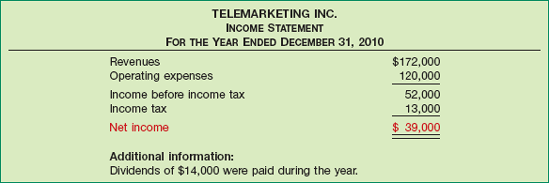

Illustration 5-27 presents the income statement and additional information.

Preparing the statement of cash flows from these sources involves four steps:

Determine the cash provided by (or used in) operating activities.

Determine the cash provided by or used in investing and financing activities.

Determine the change (increase or decrease) in cash during the period.

Reconcile the change in cash with the beginning and the ending cash balances.

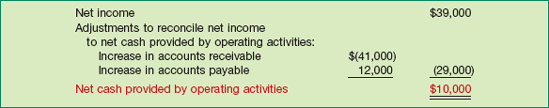

Cash provided by operating activities is the excess of cash receipts over cash payments from operating activities. Companies determine this amount by converting net income on an accrual basis to a cash basis. To do so, they add to or deduct from net income those items in the income statement that do not affect cash. This procedure requires that a company analyze not only the current year's income statement but also the comparative balance sheets and selected transaction data.

Analysis of Telemarketing's comparative balance sheets reveals two items that will affect the computation of net cash provided by operating activities:

The increase in accounts receivable reflects a noncash increase of $41,000 in revenues.

The increase in accounts payable reflects a noncash increase of $12,000 in expenses.

Therefore, to arrive at cash provided by operations, Telemarketing Inc. deducts from net income the increase in accounts receivable ($41,000), and it adds back to net income the increase in accounts payable ($12,000). As a result of these adjustments, the company determines cash provided by operations to be $10,000, computed as shown in Illustration 5-28.

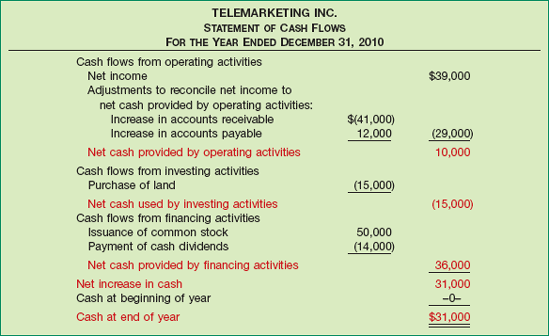

Next, the company determines its investing and financing activities. Telemarketing Inc.'s only investing activity was the land purchase. It had two financing activities: (1) Common stock increased $50,000 from the issuance of 50,000 shares for cash. (2) The company paid $14,000 cash in dividends. Knowing the amounts provided/used by operating, investing, and financing activities, the company determines the net increase in cash. Illustration 5-29 presents Telemarketing Inc.'s statement of cash flows for 2010.

The increase in cash of $31,000 reported in the statement of cash flows agrees with the increase of $31,000 in cash calculated from the comparative balance sheets.

Not all of a company's significant activities involve cash. Examples of significant noncash activities are:

Issuance of common stock to purchase assets.

Conversion of bonds into common stock.

Issuance of debt to purchase assets.

Exchanges of long-lived assets.

Significant financing and investing activities that do not affect cash are not reported in the body of the statement of cash flows. Rather, these activities are reported in either a separate schedule at the bottom of the statement of cash flows or in separate notes to the financial statements. Such reporting of these noncash activities satisfies the full disclosure principle.

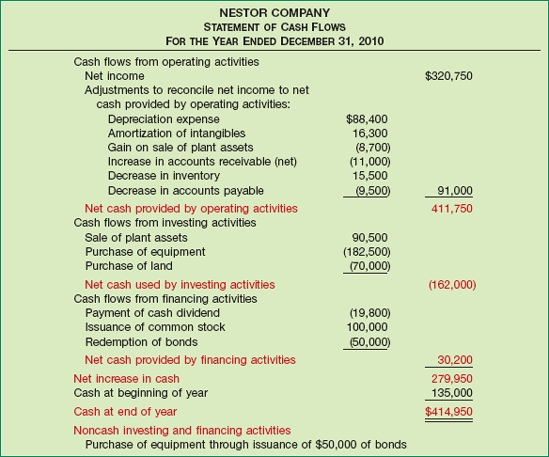

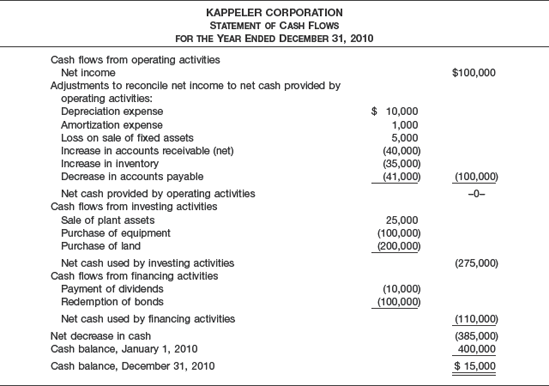

Illustration 5-30 shows an example of a comprehensive statement of cash flows. Note that the company purchased equipment through the issuance of $50,000 of bonds, which is a significant noncash transaction. In solving homework assignments, you should present significant noncash activities in a separate schedule at the bottom of the statement of cash flows.

"Happiness is a positive cash flow" is certainly true. Although net income provides a long-term measure of a company's success or failure, cash is its lifeblood. Without cash, a company will not survive. For small and newly developing companies, cash flow is the single most important element for survival. Even medium and large companies must control cash flow.

Creditors examine the cash flow statement carefully because they are concerned about being paid. They begin their examination by finding net cash provided by operating activities. A high amount indicates that a company is able to generate sufficient cash from operations to pay its bills without further borrowing. Conversely, a low or negative amount of net cash provided by operating activities indicates that a company may have to borrow or issue equity securities to acquire sufficient cash to pay its bills. Consequently, creditors look for answers to the following questions in the company's cash flow statements.

How successful is the company in generating net cash provided by operating activities?

What are the trends in net cash flow provided by operating activities over time?

What are the major reasons for the positive or negative net cash provided by operating activities?

You should recognize that companies can fail even though they report net income. The difference between net income and net cash provided by operating activities can be substantial. Companies such as W. T. Grant Company and Prime Motor Inn, for example, reported high net income numbers but negative net cash provided by operating activities. Eventually both companies filed for bankruptcy.

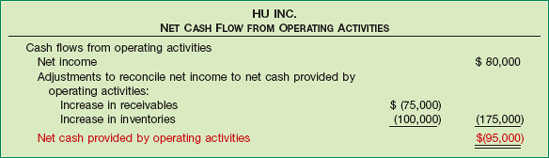

In addition, substantial increases in receivables and/or inventory can explain the difference between positive net income and negative net cash provided by operating activities. For example, in its first year of operations Hu Inc. reported a net income of $80,000. Its net cash provided by operating activities, however, was a negative $95,000, as shown in Illustration 5-31.

Hu could easily experience a "cash crunch" because it has its cash tied up in receivables and inventory. If Hu encounters problems in collecting receivables, or if inventory moves slowly or becomes obsolete, its creditors may have difficulty collecting on their loans.

Analysts increasingly use cash-flow-based measures of income, such as cash flow provided by operations, instead of or in addition to net income. The reason for the change is that they have been losing faith in accrual-accounting–based net income numbers.

Sadly, these days even cash flow from operations isn't always what it seems to be. For example, in 2002 WorldCom, Inc. disclosed that it had improperly capitalized expenses: It moved $3.8 billion of cash outflows from the "Cash from operating activities" section of the cash flow statement to the "Investing activities" section, thereby greatly enhancing cash provided by operating activities.

Similarly, in 2006 Pier 1 Imports restated its cash flow statements for 2005 and 2004. The problem? Pier 1 had improperly classified as an operating cash flow some payments received on the sale of receivables. Those payments should have been reported in the investing section. The restatement resulted in a $164 million, or 64%, decline in operating cash flow in 2005 (and a $51 million or 47% decline in 2004).

Source: Henny Sender, "Sadly, These Days Even Cash Flow Isn't Always What It Seems To Be," Wall Street Journal Online (May 8, 2002); and Jack Ciesielski, "Pier 1: Cash Flow Spring Cleaning," The AAO Weblog, www.accountingobserver.com/blog/ (April 6, 2006).

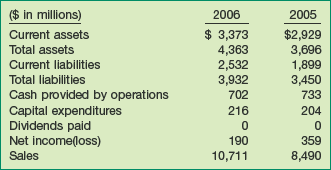

Readers of financial statements often assess liquidity by using the current cash debt coverage ratio. It indicates whether the company can pay off its current liabilities from its operations in a given year. Illustration 5-32 shows the formula for this ratio.

The higher the current cash debt coverage ratio, the less likely a company will have liquidity problems. For example, a ratio near 1:1 is good: It indicates that the company can meet all of its current obligations from internally generated cash flow.

The cash debt coverage ratio provides information on financial flexibility. It indicates a company's ability to repay its liabilities from net cash provided by operating activities, without having to liquidate the assets employed in its operations. Illustration 5-33 shows the formula for this ratio. Notice its similarity to the current cash debt coverage ratio. However, because it uses average total liabilities in place of average current liabilities, it takes a somewhat longer-range view.

The higher this ratio, the less likely the company will experience difficulty in meeting its obligations as they come due. It signals whether the company can pay its debts and survive if external sources of funds become limited or too expensive.

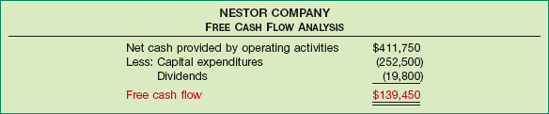

A more sophisticated way to examine a company's financial flexibility is to develop a free cash flow analysis. Free cash flow is the amount of discretionary cash flow a company has. It can use this cash flow to purchase additional investments, retire its debt, purchase treasury stock, or simply add to its liquidity. Financial statement users calculate free cash flow as shown in Illustration 5-34.

In a free cash flow analysis, we first deduct capital spending, to indicate it is the least discretionary expenditure a company generally makes. (Without continued efforts to maintain and expand facilities, it is unlikely that a company can continue to maintain its competitive position.) We then deduct dividends. Although a company can cut its dividend, it usually will do so only in a financial emergency. The amount resulting after these deductions is the company's free cash flow. Obviously, the greater the amount of free cash flow, the greater the company's amount of financial flexibility.

Questions that a free cash flow analysis answers are:

Is the company able to pay its dividends without resorting to external financing?

If business operations decline, will the company be able to maintain its needed capital investment?

What is the amount of discretionary cash flow that can be used for additional investment, retirement of debt, purchase of treasury stock, or addition to liquidity?

Illustration 5-35 is a free cash flow analysis using the cash flow statement for Nestor Company (shown in Illustration 5-30).

This computation shows that Nestor has a positive, and substantial, net cash provided by operating activities of $411,750. Nestor's statement of cash flows reports that the company purchased equipment of $182,500 and land of $70,000 for total capital spending of $252,500. Nestor has more than sufficient cash flow to meet its dividend payment and therefore has satisfactory financial flexibility.

As you can see from looking back at Illustration 5-30, Nestor used its free cash flow to redeem bonds and add to its liquidity. If it finds additional investments that are profitable, it can increase its spending without putting its dividend or basic capital spending in jeopardy. Companies that have strong financial flexibility can take advantage of profitable investments even in tough times. In addition, strong financial flexibility frees companies from worry about survival in poor economic times. In fact, those with strong financial flexibility often fare better in a poor economy because they can take advantage of opportunities that other companies cannot.

As in U.S. GAAP, the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows are required statements for iGAAP. In addition, the content and presentation of an iGAAP balance sheet and cash flow statement are similar to those used for U.S. GAAP. In general, the disclosure requirements related to the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows are much more extensive and detailed in the U.S. IAS 1, "Presentation of Financial Statements," provides the overall iGAAP requirements for balance sheet information. IAS 7, "Cash Flow Statements," provides the overall iGAAP requirements for cash flow information.

iGAAP requires that specific items be reported on the balance sheet. No such general standard exists in U.S. GAAP. However under U.S. GAAP, public companies must follow SEC regulations, which require specific line items. In addition, specific U.S. GAAP standards mandate certain forms of reporting balance sheet information.

There are many similarities between U.S. and iGAAP related to balance sheet presentation. For example:

—IAS 1 specifies minimum note disclosures, similar to U.S. GAAP on accounting policies and judgments. These must include information about (1) accounting policies followed, (2) judgments that management has made in the process of applying the entity's accounting policies, and (3) the key assumptions and estimation uncertainty that could result in a material adjustment to the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities within the next financial year.

—Comparative prior-period information must be presented and financial statements must be prepared annually.

—Current/noncurrent classification for assets and liabilities is normally required. In general, post–balance sheet events are not considered in classifying items as current or noncurrent.

Interestingly, iGAAP statements may report property, plant, and equipment first in the balance sheet. Some companies report the subtotal "net assets," which equals total assets minus total liabilities.

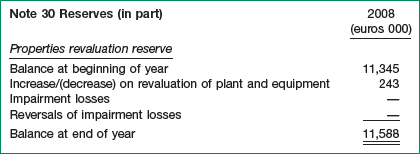

While the use of the term "reserve" is discouraged in U.S. GAAP, there is no such prohibition in iGAAP.

U.S. GAAP and iGAAP differ in the iGAAP provision for balance sheet revaluations of property, plant, and equipment. Under the revaluation model, revaluations are recorded and reported as part of stockholders' equity. To illustrate, Richardson Company uses iGAAP and has property and equipment on an historical cost basis of 2,000,000 euros. At the end of the year, Richardson appraises its property and equipment and determines it had a revaluation increase of 243,000 euros. Richardson records this revaluation under iGAAP with an increase to property and equipment as well as a valuation reserve in stockholders' equity. A note to the financial statements explains the change in the revaluation equity account from one period to the next, as shown below for Richardson Company, assuming a beginning balance of 11,345,000 euros.

The IASB and the FASB are working on a project to converge their standards related to financial statement presentation. A key feature of the proposed framework is that each of the statements will be organized, in the same format, to separate an entity's financing activities from its operating and investing activities and, further, to separate financing activities into transactions with owners and creditors. Thus, the same classifications used in the balance sheet would also be used in the income statement and the statement of cash flows. The project has three phases. You can follow the joint financial presentation project at the following link: http://www.fasb.org/project/financial_statement_presentation.shtml.

Three limitations of a balance sheet are: (1) The balance sheet does not reflect fair value because accountants use a historical cost basis in valuing and reporting most assets and liabilities. (2) Companies must use judgments and estimates to determine certain amounts, such as the collectibility of receivables and the useful life of long-term tangible and intangible assets. (3) The balance sheet omits many items that are of financial value to the business but cannot be recorded objectively, such as human resources, customer base, and reputation.

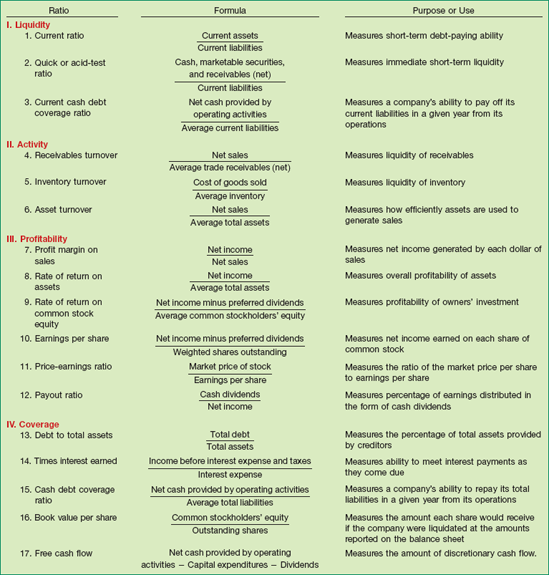

Analysts and other interested parties can gather qualitative information from financial statements by examining relationships between items on the statements and identifying trends in these relationships. A useful starting point in developing this information is ratio analysis.

A ratio expresses the mathematical relationship between one quantity and another. Ratio analysis expresses the relationship among pieces of selected financial statement data, in a percentage, a rate, or a simple proportion.

To illustrate, IBM Corporation recently had current assets of $46,970 million and current liabilities of $39,798 million. We find the ratio between these two amounts by dividing current assets by current liabilities. The alternative means of expression are:

- Percentage:

Current assets are 118% of current liabilities.

- Rate:

Current assets are 1.18 times as great as current liabilities.

- Proportion:

The relationship of current assets to current liabilities is 1.18:1.

To analyze financial statements, we classify ratios into four types, as follows:

In Chapter 5 we discussed three measures related to the statement of cash flows (the current cash debt coverage and cash debt coverage ratios, and free cash flow). Throughout the remainder of the textbook, we provide ratios to help you understand and interpret the information presented in financial statements. Illustration 5A-1 presents the ratios that we will use throughout the text. You should find this chart helpful as you examine these ratios in more detail in the following chapters. An appendix to Chapter 24 further discusses financial statement analysis.

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVE FOR APPENDIX 5A

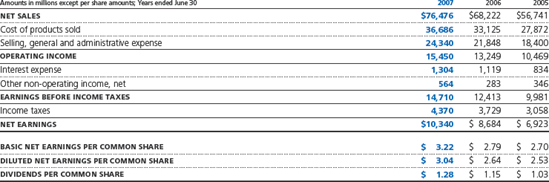

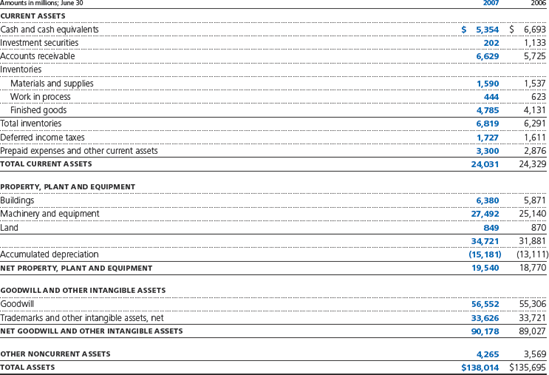

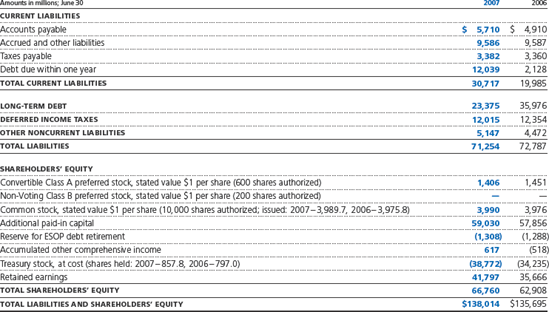

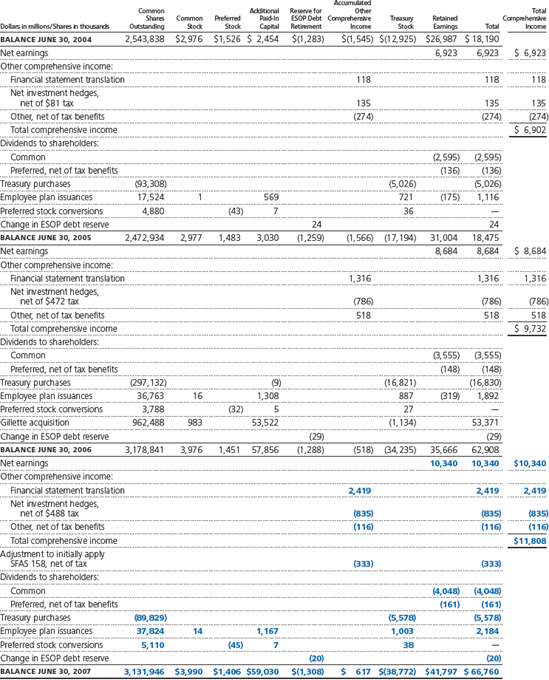

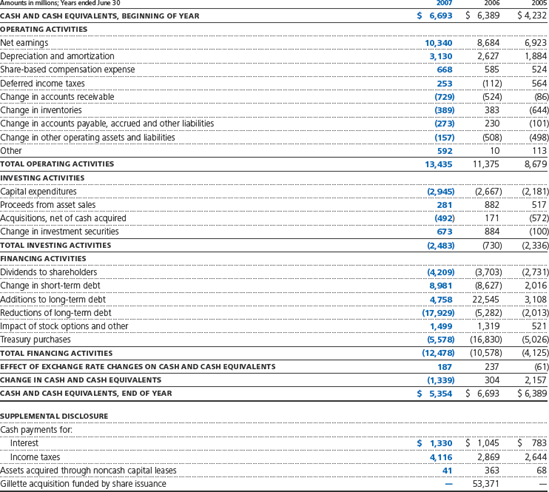

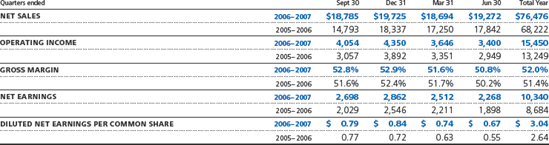

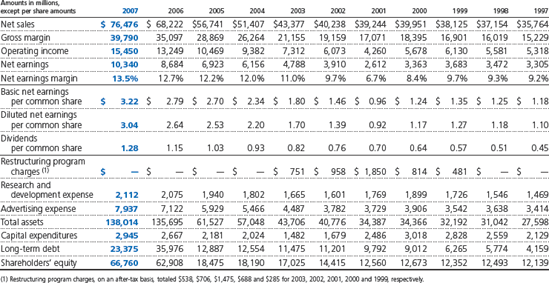

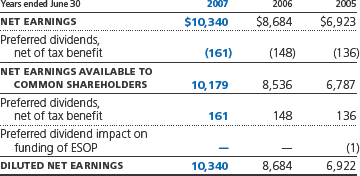

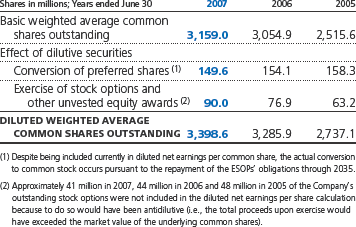

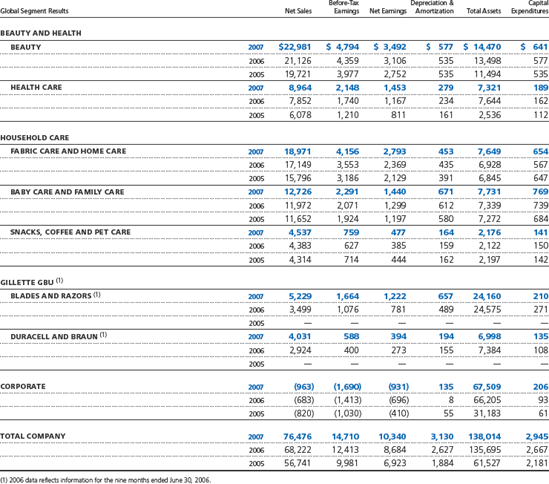

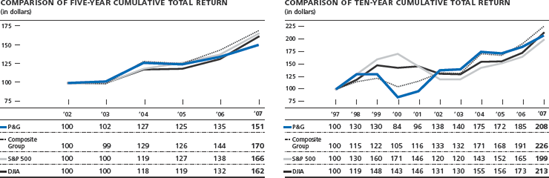

The following pages contain the financial statements, accompanying notes, and other information from the 2007 annual report of The Procter & Gamble Company (P&G). The Procter & Gamble Company manufactures and markets a range of consumer products in various countries throughout the world. The company markets over 300 branded products in more than 160 countries. It manages its business in five product segments: Fabric and Home Care, Baby and Family Care, Beauty Care, Health Care, and Snacks and Beverages.

We do not expect that you will comprehend P&G's financial statements and the accompanying notes in their entirety at your first reading. But we expect that by the time you complete the material in this textbook, your level of understanding and interpretive ability will have grown enormously.

At this point we recommend that you take 20 to 30 minutes to scan the following statements and notes. Your goal should be to familiarize yourself with the contents and accounting elements. Throughout the following 19 chapters, when you are asked to refer to specific parts of P&G's financial statements, do so! Then, when you have completed reading this book, we challenge you to reread P&G's financials to see how much greater and more sophisticated your understanding of them has become.

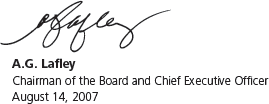

We've grown P&G sales from $39 billion to $76 billion in the past seven years. We've more than doubled the number of brands that generate $1 billion or more in sales each year, and now have 23 of these leading billion-dollar brands in our portfolio. We've more than quadrupled the number of brands that generate at least $500 million in sales, and now have 18 of these brands poised to be our next billion-dollar brands. We've nearly doubled the number of countries in which P&G generates a billion dollars or more in sales each year, and now have 12 billion-dollar countries. We do more than a billion dollars in sales each year with seven retail customers, up from two in 2001. We've generated more than $43 billion in net earnings and $50 billion in free cash flow. P&G's market capitalization has increased more than $100 billion since 2001, and today the Company is among the ten most valuable companies in the U.S.

The critical question now for P&G shareholders, prospective investors, and Company management is: "How do we keep a company of P&G's size growing?"

Opportunities for growth remain substantial in each of our strategic focus areas.

P&G's Core. We are widening P&G's share advantages versus competition. For example, in fabric care, we were the number two player globally in the early 1990s. Today, P&G has a 34% share of the global fabric care market, nearly double the next competitor, and we've grown share for six consecutive years. We have a lot of opportunity to keep growing all of P&G's billion-dollar brands. We're proving in category after category that a leading share, even a relatively high share, is not a barrier to growth. We will continue to leverage our brand lineup and category-leading innovation to keep core businesses healthy and growing.

Faster-Growing, Higher-Margin Businesses. We have even greater upside in businesses such as beauty and health care. The beauty and health categories in which P&G competes are a combined $360 billion market today, and are projected to grow 3% to 4% a year for the balance of the decade. P&G has nearly doubled its share of beauty and health over the past decade, and yet P&G's share of this combined market is only about 10% globally.

Developing Markets and Lower-Income Consumers. We can still grow substantially in developing markets by increasing household penetration and consumer usage frequency, and by entering categories where we're not yet competing. For example, the average U.S. household buys five to ten times as much P&G product per year as the average household in developing markets. In addition, there is a large number of households in developing regions that do not yet purchase any P&G product. Closing this gap, which we're confident we can do over time, will continue to drive strong growth for years to come.

There are significant bottom-line growth opportunities, as well. We'll continue to leverage P&G's scale. We'll reduce overhead costs by simplifying the way we work and eliminating duplication between global business units and market development organizations. We'll be more effective and efficient in how we manage our smaller country organizations and brands. And we'll continue to increase productivity in every one of our businesses.

We'll also continue to improve gross margins. The Company's current gross margin is about 52%. We can earn a higher total-company margin by achieving best-in-class margins in more categories and business units. Based on industry benchmarking, we believe that only about half of P&G businesses have gross margins better than their competitive peer set. As we get more of our businesses to best-in-class levels, we'll increase our total-company margin.

A COMPANY DESIGNED TO GROW

We're focused on these opportunities, realistic about challenges, and confident P&G's design for growth will enable us to keep P&G growing. Over the next few years, our portfolio will continue to shift toward faster-growing, higher-margin businesses. We'll extend the advantages we've created with our core strengths. We'll make the disciplined choices required to create even more shareholder value. We'll continue to develop the industry's strongest, broadest and deepest leadership bench.

And we'll continue to focus on inspiring and enabling P&G people to fulfill our Company's Purpose: improving consumers' lives in small but always meaningful ways every day. This is critical. Our design for growth reflects the management choices we've made to create the opportunities and capability for growth—but it's P&G people who deliver it. Their performance in fiscal 2007 was outstanding once again, and their capability, creativity and potential will ensure P&G out-performs the consumer products industry year after year.

At The Procter & Gamble Company, we take great pride in our long history of doing what's right. If you analyze what's made our company successful over the years, you may focus on our brands, our marketing strategies, our organization design and our ability to innovate. But if you really want to get at what drives our company's success, the place to look is our people. Our people are deeply committed to our Purpose, Values and Principles. It is this commitment to doing what's right that unites us.

This commitment to doing what's right is embodied in our financial reporting. High-quality financial reporting is our responsibility—one we execute with integrity, and within both the letter and spirit of the law.

High-quality financial reporting is characterized by accuracy, objectivity and transparency. Management is responsible for maintaining an effective system of internal controls over financial reporting to deliver those characteristics in all material respects. The Board of Directors, through its Audit Committee, provides oversight. We have engaged Deloitte & Touche LLP to audit our Consolidated Financial Statements, on which they have issued an unqualified opinion.

Our commitment to providing timely, accurate and understandable information to investors encompasses:

Communicating expectations to employees. Every employee—from senior management on down—is trained on the Company's Worldwide Business Conduct Manual, which sets forth the Company's commitment to conduct its business affairs with high ethical standards. Every employee is held personally accountable for compliance and is provided several means of reporting any concerns about violations of the Worldwide Business Conduct Manual, which is available on our website at www.pg.com.

Maintaining a strong internal control environment. Our system of internal controls includes written policies and procedures, segregation of duties and the careful selection and development of employees. The system is designed to provide reasonable assurance that transactions are executed as authorized and appropriately recorded, that assets are safeguarded and that accounting records are sufficiently reliable to permit the preparation of financial statements conforming in all material respects with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America. We monitor these internal controls through control self-assessments conducted by business unit management. In addition to performing financial and compliance audits around the world, including unannounced audits, our Global Internal Audit organization provides training and continuously improves internal control processes. Appropriate actions are taken by management to correct any identified control deficiencies.

Executing financial stewardship. We maintain specific programs and activities to ensure that employees understand their fiduciary responsibilities to shareholders. This ongoing effort encompasses financial discipline in strategic and daily business decisions and brings particular focus to maintaining accurate financial reporting and effective controls through process improvement, skill development and oversight.

Exerting rigorous oversight of the business. We continuously review business results and strategic choices. Our Global Leadership Council is actively involved—from understanding strategies to reviewing key initiatives, financial performance and control assessments. The intent is to ensure we remain objective, identify potential issues, continuously challenge each other and ensure recognition and rewards are appropriately aligned with results.

Engaging our Disclosure Committee. We maintain disclosure controls and procedures designed to ensure that information required to be disclosed is recorded, processed, summarized and reported timely and accurately. Our Disclosure Committee is a group of senior-level executives responsible for evaluating disclosure implications of significant business activities and events. The Committee reports its findings to the CEO and CFO, providing an effective process to evaluate our external disclosure obligations.

Encouraging strong and effective corporate governance from our Board of Directors. We have an active, capable and diligent Board that meets the required standards for independence, and we welcome the Board's oversight. Our Audit Committee comprises independent directors with significant financial knowledge and experience. We review significant accounting policies, financial reporting and internal control matters with them and encourage their independent discussions with external auditors. Our corporate governance guidelines, as well as the charter of the Audit Committee and certain other committees of our Board, are available on our website at www.pg.com.

P&G has a strong history of doing what's right. Our employees embrace our Purpose, Values and Principles. We take responsibility for the quality and accuracy of our financial reporting. We present this information proudly, with the expectation that those who use it will understand our company, recognize our commitment to performance with integrity and share our confidence in P&G's future.

Management is responsible for establishing and maintaining adequate internal control over financial reporting of The Procter & Gamble Company (as defined in Rule 13a-15(f) under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended). Our internal control over financial reporting is designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding the reliability of financial reporting and the preparation of financial statements for external purposes in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles in the United States of America.

Strong internal controls is an objective that is reinforced through our Worldwide Business Conduct Manual, which sets forth our commitment to conduct business with integrity, and within both the letter and the spirit of the law. The Company's internal control over financial reporting includes a Control Self-Assessment Program that is conducted annually by substantially all areas of the Company and is audited by the internal audit function. Management takes the appropriate action to correct any identified control deficiencies. Because of its inherent limitations, any system of internal control over financial reporting, no matter how well designed, may not prevent or detect misstatements due to the possibility that a control can be circumvented or overridden or that misstatements due to error or fraud may occur that are not detected. Also, because of changes in conditions, internal control effectiveness may vary over time.

Management assessed the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting as of June 30, 2007, using criteria established in Internal Control—Integrated Framework issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) and concluded that the Company maintained effective internal control over financial reporting as of June 30, 2007, based on these criteria.

Deloitte & Touche LLP, an independent registered public accounting firm, has audited the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting and management's assessment of the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting as of June 30, 2007, as stated in their report which is included herein.

August 14, 2007

To the Board of Directors and Shareholders of The Procter & Gamble Company

We have audited the accompanying Consolidated Balance Sheets of The Procter & Gamble Company and subsidiaries (the "Company") as of June 30, 2007 and 2006, and the related Consolidated Statements of Earnings, Shareholders' Equity, and Cash Flows for each of the three years in the period ended June 30, 2007. These financial statements are the responsibility of the Company's management. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audits.

We conducted our audits in accordance with the standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (United States). Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. An audit also includes assessing the accounting principles used and significant estimates made by management, as well as evaluating the overall financial statement presentation. We believe that our audits provide a reasonable basis for our opinion.

In our opinion, such Consolidated Financial Statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the Company at June 30, 2007 and 2006, and the results of its operations and cash flows for each of the three years in the period ended June 30, 2007, in conformity with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America.

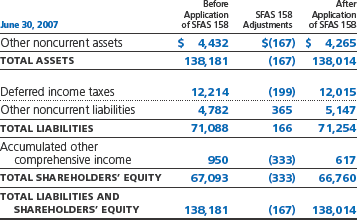

As discussed in Note 1 to the Consolidated Financial Statements, the Company adopted the provisions of SFAS No. 158, "Employers' Accounting for Defined Benefit Pension and Other Postretirement Plans, an amendment of FASB Statements No. 87, 88, 106, and 132(R)," effective June 30, 2007.

We have also audited, in accordance with the standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (United States), the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting as of June 30, 2007, based on the criteria established in Internal Control—Integrated Framework issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission and our report dated August 14, 2007, expressed an unqualified opinion on management's assessment of the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting and an unqualified opinion on the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting.

To the Board of Directors and Shareholders of The Procter & Gamble Company

We have audited management's assessment, included in Management's Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting, that The Procter & Gamble Company and subsidiaries (the "Company") maintained effective internal control over financial reporting as of June 30, 2007, based on criteria established in Internal Control—Integrated Framework issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission. The Company's management is responsible for maintaining effective internal control over financial reporting and for its assessment of the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on management's assessment and an opinion on the effectiveness of the Company's internal control over financial reporting based on our audit.

We conducted our audit in accordance with the standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (United States). Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether effective internal control over financial reporting was maintained in all material respects. Our audit included obtaining an understanding of internal control over financial reporting, evaluating management's assessment, testing and evaluating the design and operating effectiveness of internal control, and performing such other procedures as we considered necessary in the circumstances. We believe that our audit provides a reasonable basis for our opinions.