LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

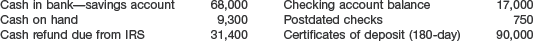

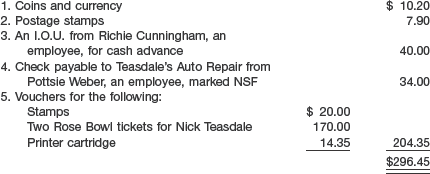

Cash, the most liquid of assets, is the standard medium of exchange and the basis for measuring and accounting for all other items. Companies generally classify cash as a current asset. Cash consists of coin, currency, and available funds on deposit at the bank. Negotiable instruments such as money orders, certified checks, cashier's checks, personal checks, and bank drafts are also viewed as cash. What about savings accounts? Banks do have the legal right to demand notice before withdrawal. But, because banks rarely demand prior notice, savings accounts nevertheless are considered cash.

Some negotiable instruments provide small investors with an opportunity to earn interest. These items, more appropriately classified as temporary investments than as cash, include money market funds, money market savings certificates, certificates of deposit (CDs), and similar types of deposits and "short-term paper."[79] These securities usually contain restrictions or penalties on their conversion to cash. Money market funds that provide checking account privileges, however, are usually classified as cash.

Certain items present classification problems: Companies treat postdated checks and I.O.U.s as receivables. They also treat travel advances as receivables if collected from employees or deducted from their salaries. Otherwise, companies classify the travel advance as a prepaid expense. Postage stamps on hand are classified as part of office supplies inventory or as a prepaid expense. Because petty cash funds and change funds are used to meet current operating expenses and liquidate current liabilities, companies include these funds in current assets as cash.

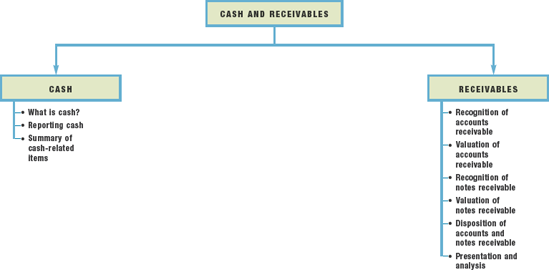

Although the reporting of cash is relatively straightforward, a number of issues merit special attention. These issues relate to the reporting of:

Cash equivalents.

Restricted cash.

Bank overdrafts.

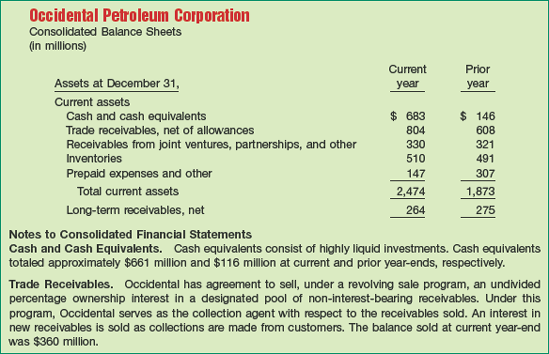

A current classification that has become popular is "Cash and cash equivalents."[80] Cash equivalents are short-term, highly liquid investments that are both (a) readily convertible to known amounts of cash, and (b) so near their maturity that they present insignificant risk of changes in interest rates. Generally, only investments with original maturities of three months or less qualify under these definitions. Examples of cash equivalents are Treasury bills, commercial paper, and money market funds. Some companies combine cash with temporary investments on the balance sheet. In these cases, they describe the amount of the temporary investments either parenthetically or in the notes.

Most individuals think of cash equivalents as cash. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Companies like Bristol-Myers Squibb and ADC Telecommunications have found out the hard way and are taking sizable write-downs on cash equivalents. Their losses resulted because they purchased auction-rate notes that declined in value. These notes carry interest rates that usually reset weekly and often have long-maturity dates (as long as 30 years). Companies argued that such notes should be classified as cash equivalents because they can be routinely traded at auction on a daily basis. (In short, they are liquid and risk-free.) Auditors agreed and permitted cash-equivalent treatment even though maturities extended well beyond three months. But when the credit crunch hit, the auctions stopped, and the value of these securities dropped because no market existed. In retrospect, the cash-equivalent classification was misleading.

It now appears likely that the FASB will eliminate the cash-equivalent classification from financial statement presentations altogether. Companies will now report only cash. If an asset is not cash and is short-term in nature, it should be reported as a temporary investment. An interesting moral to this story is that when times are good, some sloppy accounting may work. But in bad times, it quickly becomes apparent that sloppy accounting can lead to misleading and harmful effects for users of the financial statements.

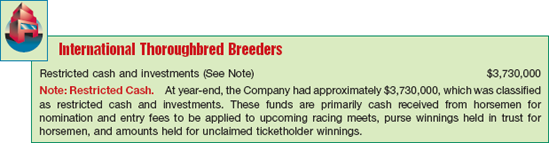

Petty cash, payroll, and dividend funds are examples of cash set aside for a particular purpose. In most situations, these fund balances are not material. Therefore, companies do not segregate them from cash in the financial statements. When material in amount, companies segregate restricted cash from "regular" cash for reporting purposes. Companies classify restricted cash either in the current assets or in the long-term assets section, depending on the date of availability or disbursement. Classification in the current section is appropriate if using the cash for payment of existing or maturing obligations (within a year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer). On the other hand, companies show the restricted cash in the long-term section of the balance sheet if holding the cash for a longer period of time.

Cash classified in the long-term section is frequently set aside for plant expansion, retirement of long-term debt or, in the case of International Thoroughbred Breeders, for entry fee deposits.

Banks and other lending institutions often require customers to maintain minimum cash balances in checking or savings accounts. The SEC defines these minimum balances, called compensating balances, as "that portion of any demand deposit (or any time deposit or certificate of deposit) maintained by a corporation which constitutes support for existing borrowing arrangements of the corporation with a lending institution. Such arrangements would include both outstanding borrowings and the assurance of future credit availability." [1]

To avoid misleading investors about the amount of cash available to meet recurring obligations, the SEC recommends that companies state separately legally restricted deposits held as compensating balances against short-term borrowing arrangements among the "Cash and cash equivalent items" in current assets. Companies should classify separately restricted deposits held as compensating balances against long-term borrowing arrangements as noncurrent assets in either the investments or other assets sections, using a caption such as "Cash on deposit maintained as compensating balance." In cases where compensating balance arrangements exist without agreements that restrict the use of cash amounts shown on the balance sheet, companies should describe the arrangements and the amounts involved in the notes.

Bank overdrafts occur when a company writes a check for more than the amount in its cash account. Companies should report bank overdrafts in the current liabilities section, adding them to the amount reported as accounts payable. If material, companies should disclose these items separately, either on the face of the balance sheet or in the related notes.[81]

Bank overdrafts are generally not offset against the cash account. A major exception is when available cash is present in another account in the same bank on which the overdraft occurred. Offsetting in this case is required.

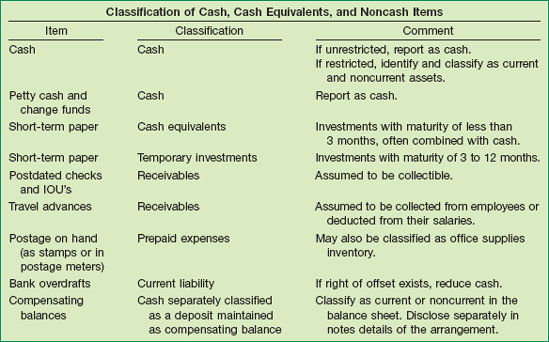

Cash and cash equivalents include the medium of exchange and most negotiable instruments. If the item cannot be quickly converted to coin or currency, a company separately classifies it as an investment, receivable, or prepaid expense. Companies segregate and classify cash that is unavailable for payment of currently maturing liabilities in the long-term assets section. Illustration 7-2 summarizes the classification of cash-related items.

Some companies really know how to fill up the piggy bank. But is that a good thing?

Unlike most American consumers, whose failure to save has exasperated economists for years, the typical U.S. corporation has increased its savings so sharply that it probably has enough cash on hand to pay off its debts completely.

That should be good news in an economy unsettled by rising energy prices, tightening credit, gyrating stock prices, and declining values for the dollar and the family homestead. Indeed, the Federal Reserve chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, cited strong corporate balance sheets as a bright spot in an otherwise darkening forecast for the economy.

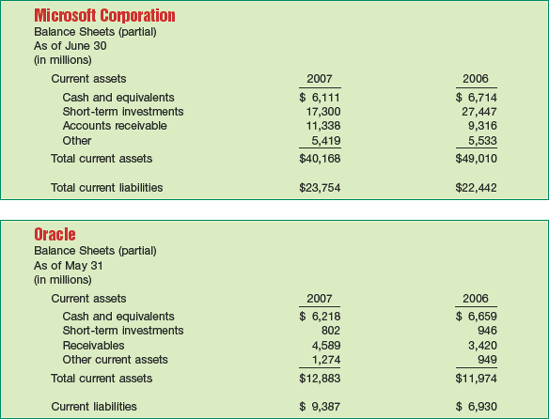

As one commentator noted, "Cash as a percent of total assets is as high as it's been since the 1960s." The ledgers of many individual companies bear out these findings. For example, the cash ratio—cash and short-term investments as a percent of total assets—at Paychex has more than doubled, from less than 30 percent in 1988 to more than 70 percent by summer 2007. Over the same period, Apple's cash ratio grew to more than 60 percent, from just over 38 percent.

Similarly, the cash ratio at Avon Products, just under 3 percent in 1988, was nearly 17 percent by December 2007. And Microsoft's savings account is so large that its chief financial officer has observed that the company could, if it wished, cover from its own reserves most of the $20 billion cash component of its pending $44.6 billion offer for Yahoo.

Those who study corporate balance sheets suggest that several factors have contributed to this change in corporate savings patterns. In the last 25 years, the speed and scale of globalization have increased sharply. That shift to worldwide markets confronted companies with increased currency risks, political risks, and new competition—all adding to the overall risk of doing business. During the same period, conglomerates and similarly diversified companies fell out of favor, as Wall Street looked for "pure plays" and companies narrowed their focus to a few core businesses—in effect, putting more of their eggs in fewer baskets. That left those companies more vulnerable to any event that shook those baskets.

Source: Adapted from D. Henriques, "Unlike Consumers, Companies Are Piling Up Cash," New York Times (March 4, 2008).

Receivables are claims held against customers and others for money, goods, or services. For financial statement purposes, companies classify receivables as either current (short-term) or noncurrent (long-term). Companies expect to collect current receivables within a year or during the current operating cycle, whichever is longer. They classify all other receivables as noncurrent. Receivables are further classified in the balance sheet as either trade or nontrade receivables.

Customers often owe a company amounts for goods bought or services rendered. A company may subclassify these trade receivables, usually the most significant item it possesses, into accounts receivable and notes receivable. Accounts receivable are oral promises of the purchaser to pay for goods and services sold. They represent "open accounts" resulting from short-term extensions of credit. A company normally collects them within 30 to 60 days. Notes receivable are written promises to pay a certain sum of money on a specified future date. They may arise from sales, financing, or other transactions. Notes may be short-term or long-term.

Nontrade receivables arise from a variety of transactions. Some examples of nontrade receivables are:

Advances to officers and employees.

Advances to subsidiaries.

Deposits paid to cover potential damages or losses.

Dividends and interest receivable.

Claims against:

Insurance companies for casualties sustained.

Defendants under suit.

Governmental bodies for tax refunds.

Common carriers for damaged or lost goods.

Creditors for returned, damaged, or lost goods.

Customers for returnable items (crates, containers, etc.).

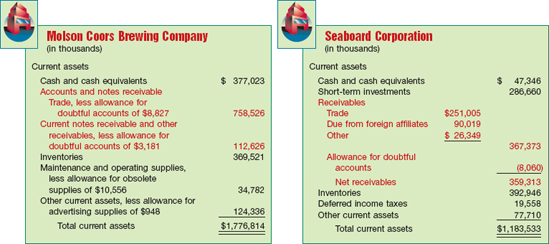

Because of the peculiar nature of nontrade receivables, companies generally report them as separate items in the balance sheet. Illustration 7-3 shows the reporting of trade and nontrade receivables in the balance sheets of Molson Coors Brewing Company and Seaboard Corporation.

The basic issues in accounting for accounts and notes receivable are the same: recognition, valuation, and disposition. We discuss these basic issues for accounts and notes receivable next.

In most receivables transactions, the amount to be recognized is the exchange price between the two parties. The exchange price is the amount due from the debtor (a customer or a borrower). Some type of business document, often an invoice, serves as evidence of the exchange price. Two factors may complicate the measurement of the exchange price: (1) the availability of discounts (trade and cash discounts), and (2) the length of time between the sale and the due date of payments (the interest element).

Prices may be subject to a trade or quantity discount. Companies use such trade discounts to avoid frequent changes in catalogs, to alter prices for different quantities purchased, or to hide the true invoice price from competitors.

Trade discounts are commonly quoted in percentages. For example, say your textbook has a list price of $90, and the publisher sells it to college bookstores for list less a 30 percent trade discount. The publisher then records the receivable at $63 per textbook. The publisher, per normal practice, simply deducts the trade discount from the list price and bills the customer net.

As another example, Maxwell House at one time sold a 10-ounce jar of its instant coffee listing at $5.85 to supermarkets for $5.05, a trade discount of approximately 14 percent. The supermarkets in turn sold the instant coffee for $5.20 per jar. Maxwell House records the receivable and related sales revenue at $5.05 per jar, not $5.85.

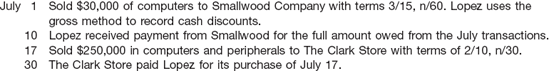

Companies offer cash discounts (sales discounts) to induce prompt payment. Cash discounts generally presented in terms such as 2/10, n/30 (2 percent if paid within 10 days, gross amount due in 30 days), or 2/10, E.O.M., net 30, E.O.M. (2 percent if paid any time before the tenth day of the following month, with full payment received by the thirtieth of the following month).

Companies usually take sales discounts unless their cash is severely limited. Why? A company that receives a 1 percent reduction in the sales price for payment within 10 days, total payment due within 30 days, effectively earns 18.25 percent (.01 ÷ [20/365]), or at least avoids that rate of interest cost.

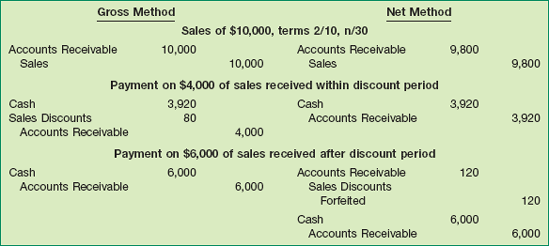

Companies usually record sales and related sales discount transactions by entering the receivable and sale at the gross amount. Under this method, companies recognize sales discounts only when they receive payment within the discount period. The income statement shows sales discounts as a deduction from sales to arrive at net sales.

Some contend that sales discounts not taken reflect penalties added to an established price to encourage prompt payment. That is, the seller offers sales on account at a slightly higher price than if selling for cash. The cash discount offered offsets the increase. Thus, customers who pay within the discount period actually purchase at the cash price. Those who pay after expiration of the discount period pay a penalty for the delay—an amount in excess of the cash price. Per this reasoning, companies record sales and receivables net. They subsequently debit any discounts not taken to Accounts Receivable and credit to Sales Discounts Forfeited. The entries in Illustration 7-4 show the difference between the gross and net methods.

If using the gross method, a company reports sales discounts as a deduction from sales in the income statement. Proper expense recognition dictates that the company also reasonably estimates the expected discounts to be taken and charges that amount against sales. If using the net method, a company considers Sales Discounts Forfeited as an "Other revenue" item.[82]

Theoretically, the recognition of Sales Discounts Forfeited is correct. The receivable is stated closer to its realizable value, and the net sales figure measures the revenue earned from the sale. As a practical matter, however, companies seldom use the net method because it requires additional analysis and bookkeeping. For example, the net method requires adjusting entries to record sales discounts forfeited on accounts receivable that have passed the discount period.

Ideally, a company should measure receivables in terms of their present value, that is, the discounted value of the cash to be received in the future. When expected cash receipts require a waiting period, the receivable face amount is not worth the amount that the company ultimately receives.

To illustrate, assume that Best Buy makes a sale on account for $1,000 with payment due in four months. The applicable annual rate of interest is 12 percent, and payment is made at the end of four months. The present value of that receivable is not $1,000 but $961.54 ($1,000 × .96154). In other words, the $1,000 Best Buy receives four months from now is not the same as the $1,000 received today.

Theoretically, any revenue after the period of sale is interest revenue. In practice, companies ignore interest revenue related to accounts receivable because the amount of the discount is not usually material in relation to the net income for the period. The profession specifically excludes from present value considerations "receivables arising from transactions with customers in the normal course of business which are due in customary trade terms not exceeding approximately one year." [2]

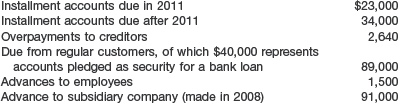

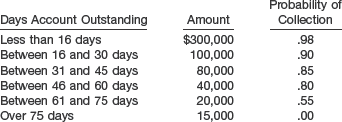

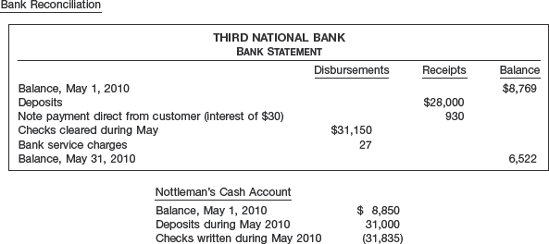

Reporting of receivables involves (1) classification and (2) valuation on the balance sheet. Classification involves determining the length of time each receivable will be outstanding. Companies classify receivables intended to be collected within a year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer, as current. All other receivables are classified as long-term.

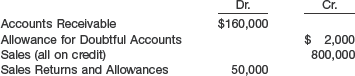

Companies value and report short-term receivables at net realizable value—the net amount they expect to receive in cash. Determining net realizable value requires estimating both uncollectible receivables and any returns or allowances to be granted.

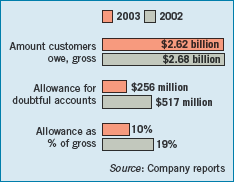

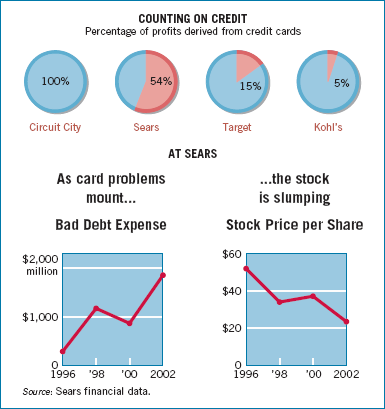

As one revered accountant aptly noted, the credit manager's idea of heaven probably would be a place where everyone (eventually) paid his or her debts.[83] The experiences of Circuit City, Sears (now Sears Holdings), Target, and Kohl's, as shown in Illustration 7-5 on the next page, indicate the importance of credit sales for many companies. Note that for Sears, increased bad debt expense led to a lower stock price, which prompted Sears to sell its credit card portfolio to Citigroup.

Sales on any basis other than cash make uncertain the possibility of collecting the account. An uncollectible account receivable is a loss of revenue that requires, through proper entry in the accounts, a decrease in the asset accounts receivable and a related decrease in income and stockholders' equity. Companies recognize the loss in revenue and the decrease in income by recording bad debt expense.

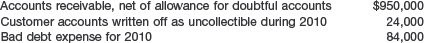

Companies use two procedures to record uncollectible accounts:

The direct write-off method records the bad debt in the period in which a company determines that it cannot collect a specific receivable. In contrast, the allowance method enters the expense on an estimated basis in the accounting period in which the sales on account occur.

Supporters of the direct write-off method (which is used for tax purposes) contend that it records facts, not estimates. It assumes that a good account receivable resulted from each sale, and that later events revealed certain accounts to be uncollectible and worthless. From a practical standpoint this method is simple and convenient to apply. But the direct write-off method is theoretically deficient: It usually fails to match costs with revenues of the period. Nor does it result in receivables being stated at estimated realizable value on the balance sheet. As a result, using the direct write-off method is not considered appropriate, except when the amount uncollectible is immaterial.

Advocates of the allowance method believe that companies should record bad debt expense in the same period as the sale, to properly match expenses and revenues and to achieve a proper carrying value for accounts receivable. They contend that although estimates are involved, companies can predict the percentage of uncollectible receivables from past experiences, present market conditions, and an analysis of the outstanding balances. Many companies set their credit policies to provide for a certain percentage of uncollectible accounts. (In fact, many feel that failure to reach that percentage means that they are losing sales due to overly restrictive credit policies.)

The FASB considers the collectibility of receivables a loss contingency. Thus, the allowance method is appropriate in situations where it is probable that an asset has been impaired and that the amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated. [3]

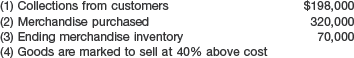

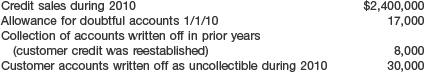

A receivable is a prospective cash inflow. The probability of its collection must be considered in valuing cash flows. These estimates normally are based either on (1) percentage of sales or (2) outstanding receivables.

If there is a fairly stable relationship between previous years' credit sales and bad debts, then a company can convert that relationship into a percentage and use it to determine this year's bad debt expense.

The percentage-of-sales approach matches costs with revenues because it relates the charge to the period in which a company records the sale. To illustrate, assume that Chad Shumway Corp. estimates from past experience that about 2 percent of credit sales become uncollectible. If Chad Shumway has credit sales of $400,000 in 2010, it records bad debt expense using the percentage-of-sales method as follows.

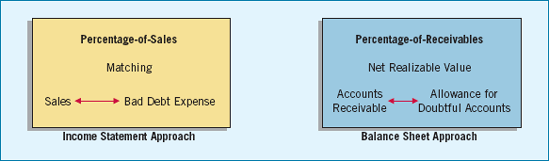

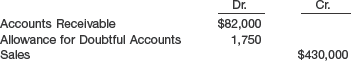

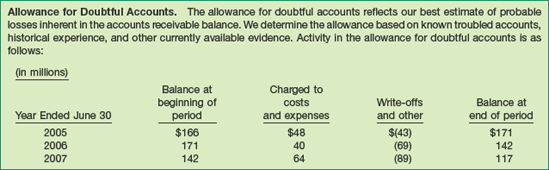

The Allowance for Doubtful Accounts is a valuation account (i.e., a contra asset), subtracted from trade receivables on the balance sheet.[84] The amount of bad debt expense and the related credit to the allowance account are unaffected by any balance currently existing in the allowance account. Because the bad debt expense estimate is related to a nominal account (Sales), any balance in the allowance is ignored. Therefore, the percentage-of-sales method achieves a proper matching of cost and revenues. This method is frequently referred to as the income statement approach.

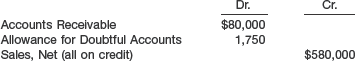

Using past experience, a company can estimate the percentage of its outstanding receivables that will become uncollectible, without identifying specific accounts. This procedure provides a reasonably accurate estimate of the receivables' realizable value. But, it does not fit the concept of matching cost and revenues. Rather, it simply reports receivables in the balance sheet at net realizable value. Hence it is referred to as the percentage-of-receivables (or balance sheet) approach.

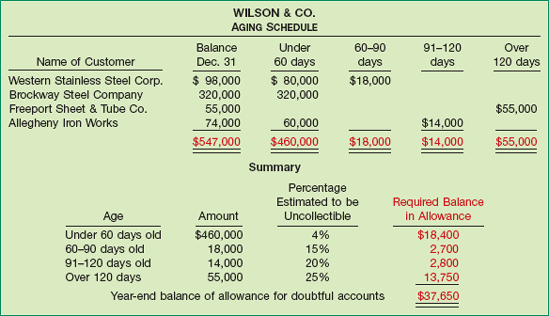

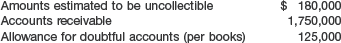

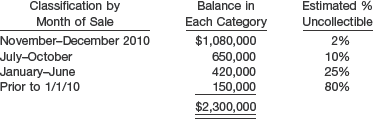

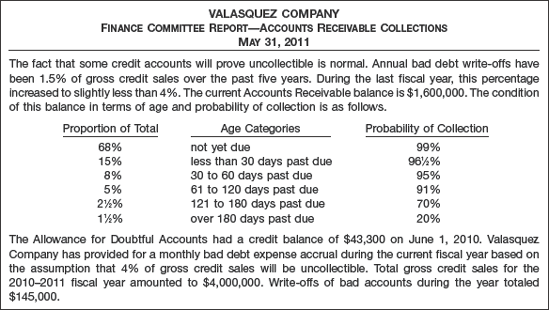

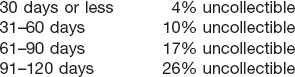

Companies may apply this method using one composite rate that reflects an estimate of the uncollectible receivables. Or, companies may set up an aging schedule of accounts receivable, which applies a different percentage based on past experience to the various age categories. An aging schedule also identifies which accounts require special attention by indicating the extent to which certain accounts are past due. The schedule of Wilson & Co. shown on page 329 is an example.

Wilson reports bad debt expense of $37,650 for this year, assuming that no balance existed in the allowance account.

To change the illustration slightly, assume that the allowance account had a credit balance of $800 before adjustment. In this case, Wilson adds $36,850 ($37,650 − $800) to the allowance account, and makes the following entry.

Wilson therefore states the balance in the Allowance account at $37,650. If the Allowance balance before adjustment had a debit balance of $200, then Wilson records bad debt expense of $37,850 ($37,650 desired balance + $200 debit balance). In the percentage-of-receivables method, Wilson cannot ignore the balance in the allowance account, because the percentage is related to a real account (Accounts Receivable).

Companies usually do not prepare an aging schedule to determine bad debt expense. Rather, they prepare it as a control device to determine the composition of receivables and to identify delinquent accounts. Companies base the estimated loss percentage developed for each category on previous loss experience and the advice of credit department personnel.

Whether using a composite rate or an aging schedule, the primary objective of the percentage of outstanding receivables method for financial statement purposes is to report receivables in the balance sheet at net realizable value. However, it is deficient in that it may not match the bad debt expense to the period in which the sale takes place.

The allowance for doubtful accounts as a percentage of receivables will vary, depending on the industry and the economic climate. Companies such as Eastman Kodak, General Electric, and Monsanto have recorded allowances ranging from $3 to $6 per $100 of accounts receivable. Other large companies, such as CPC International ($1.48), Texaco ($1.23), and USX Corp. ($0.78), have had bad debt allowances of less than $1.50 per $100. At the other extreme are hospitals that allow for $15 to $20 per $100 of accounts receivable.[85]

Target Corp. is one of the few companies that strongly increased lending in the face of the ongoing credit crisis. In fact, in a recent quarter, Target had $8.62 billion loans outstanding on its private-label Visa card, an increase of 29 percent over a year earlier. The growth in its credit card business has been the major contributor to Target's recent earnings growth. So what's the problem?

Some fear that Target is lending too much at a time when the economy is slowing. This could lead to earnings problems down the road, especially if Target is growing its credit card business by giving its cards to riskier customers. To gauge the credit-worthiness of borrowers, analysts follow a metric that tracks how much of the loan's principal is paid down each month. A low pay-down proportion indicates that borrowers are having a harder time repaying their credit card debt. Target's pay-down rate has been around 14 percent. In contrast, Discover's pay-down rate was 21 percent. Thus, it looks like Target's borrowers are slower to repay.

Investors should pay attention because Target's earnings could take a hit in the future if, as appears likely, the company will have to increase bad debt expense in order to reserve for these bad loans.

Source: P. Eavis, "Is Target Corp.'s Credit Too Generous?," Wall Street Journal (March 11, 2008), p. C1.

In summary, the percentage-of-receivables method results in a more accurate valuation of receivables on the balance sheet. From a matching viewpoint, the percentage-of-sales approach provides the better results. Illustration 7-7 relates these methods to the basic theory.

The account title employed for the allowance account is usually Allowance for Doubtful Accounts or simply Allowance.

Regardless of the method chosen, determining the expense associated with uncollectible accounts requires a large degree of judgment. Recent concern exists that, similar to Nortel in our opening story, some banks use this judgment to manage earnings. By overestimating the amounts of uncollectible loans in a good earnings year, the bank can "save for a rainy day" in a future period. In future (less-profitable) periods, banks can reduce the overly conservative allowance for loan loss account to increase earnings. In this regard, the SEC brought action against Suntrust Banks, requiring a reversal of $100 million of bad debt expense. This reversal increased aftertax profit by $61 million.[86]

When a company determines a particular account receivable to be uncollectible, it removes the balance from the books by debiting Allowance for Doubtful Accounts and crediting Accounts Receivable. If it eventually collects on a receivable that it previously wrote off, it first reestablishes the receivable by debiting Accounts Receivable and crediting Allowance for Doubtful Accounts. The company then debits Cash and credits the customer's account for the amount received.

If using the direct write-off approach, the company debits the amount collected to Cash and credits a revenue account entitled Uncollectible Amounts Recovered, with proper notation in the customer's account.

What do lenders do with uncollectible receivables? After they record bad debts on their books, they next to try to collect what they can from the deadbeat customers. Some lenders auction their bad loans in the market for distressed debt, usually paying a fee of 5–15 percent to a distressed debt broker, who arranges the sale.

Recently, several Web sites have sprung up to provide a meeting place between lenders with bad loans and collectors. These sites are sort of an "eBay of deadbeats." For example, Bank One Corp. listed $211 million of unpaid credit card receivables on DebtforSale.com (now part of DebtDepot.com). While the lendors generally recover less than 10 percent of the face value of the receivables in an auction, by going online they can reduce the costs of their bad debts. Online services charge just 0.5–1 percent for their auction services.

Source: Adapted from P. Gogoi, "An eBay of Deadbeats," Business Week (September 18, 2000), p. 124.

A note receivable is supported by a formal promissory note, a written promise to pay a certain sum of money at a specific future date. Such a note is a negotiable instrument that a maker signs in favor of a designated payee who may legally and readily sell or otherwise transfer the note to others. Although all notes contain an interest element because of the time value of money, companies classify them as interest-bearing or non-interest-bearing. Interest-bearing notes have a stated rate of interest. Zero-interest-bearing notes (non-interest-bearing) include interest as part of their face amount. Notes receivable are considered fairly liquid, even if long-term, because companies may easily convert them to cash (although they might pay a fee to do so).

Companies frequently accept notes receivable from customers who need to extend the payment period of an outstanding receivable. Or they require notes from high-risk or new customers. In addition, companies often use notes in loans to employees and subsidiaries, and in the sales of property, plant, and equipment. In some industries (e.g., the pleasure and sport boat industry) notes support all credit sales. The majority of notes, however, originate from lending transactions. The basic issues in accounting for notes receivable are the same as those for accounts receivable: recognition, valuation, and disposition.

Companies generally record short-term notes at face value (less allowances) because the interest implicit in the maturity value is immaterial. A general rule is that notes treated as cash equivalents (maturities of three months or less and easily converted to cash) are not subject to premium or discount amortization.

However, companies should record and report long-term notes receivable at the present value of the cash they expect to collect. When the interest stated on an interest-bearing note equals the effective (market) rate of interest, the note sells at face value.[87] When the stated rate differs from the market rate, the cash exchanged (present value) differs from the face value of the note. Companies then record this difference, either a discount or a premium, and amortize it over the life of a note to approximate the effective (market) interest rate. This illustrates one of the many situations in which time value of money concepts are applied to accounting measurement.

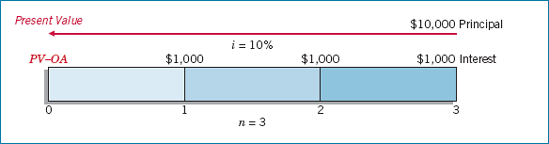

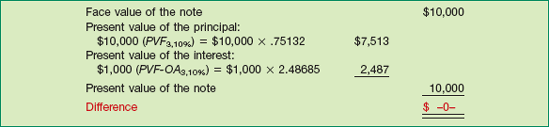

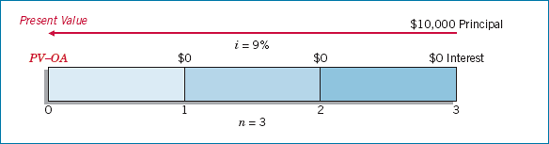

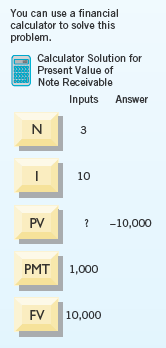

To illustrate the discounting of a note issued at face value, assume that Bigelow Corp. lends Scandinavian Imports $10,000 in exchange for a $10,000, three-year note bearing interest at 10 percent annually. The market rate of interest for a note of similar risk is also 10 percent. We show the time diagram depicting both cash flows in Illustration 7-8.

Bigelow computes the present value or exchange price of the note as follows.

In this case, the present value of the note equals its face value, because the effective and stated rates of interest are also the same. Bigelow records the receipt of the note as follows.

Bigelow recognizes the interest earned each year as follows.

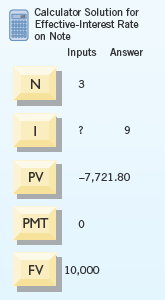

If a company receives a zero-interest-bearing note, its present value is the cash paid to the issuer. Because the company knows both the future amount and the present value of the note, it can compute the interest rate. This rate is often referred to as the implicit interest rate. Companies record the difference between the future (face) amount and the present value (cash paid) as a discount and amortize it to interest revenue over the life of the note.

To illustrate, Jeremiah Company receives a three-year, $10,000 zero-interest-bearing note, the present value of which is $7,721.80. The implicit rate that equates the total cash to be received ($10,000 at maturity) to the present value of the future cash flows ($7,721.80) is 9 percent (the present value of 1 for three periods at 9 percent is .77218). We show the time diagram depicting the one cash flow in Illustration 7-10.

Jeremiah records the transaction as follows:

The Discount on Notes Receivable is a valuation account. Companies report it on the balance sheet as a contra-asset account to notes receivable. They then amortize the discount, and recognize interest revenue annually using the effective-interest method. Illustration 7-11 shows the three-year discount amortization and interest revenue schedule.

Jeremiah records interest revenue at the end of the first year using the effective-interest method as follows.

The amount of the discount, $2,278.20 in this case, represents the interest revenue Jeremiah will receive from the note over the three years.

Often the stated rate and the effective rate differ. The zero-interest-bearing note is one example.

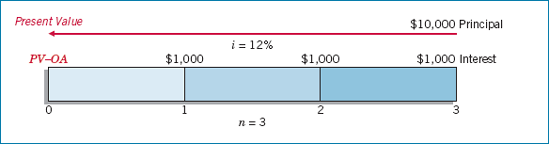

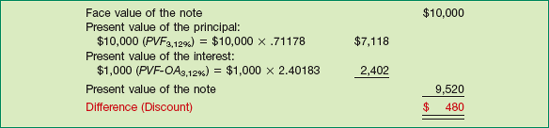

To illustrate a more common situation, assume that Morgan Corp. makes a loan to Marie Co. and receives in exchange a three-year, $10,000 note bearing interest at 10 percent annually. The market rate of interest for a note of similar risk is 12 percent. We show the time diagram depicting both cash flows in Illustration 7-12 on the next page.

Morgan computes the present value of the two cash flows as follows.

In this case, because the effective rate of interest (12 percent) exceeds the stated rate (10 percent), the present value of the note is less than the face value. That is, Morgan exchanged the note at a discount. Morgan records the receipt of the note at a discount as follows.

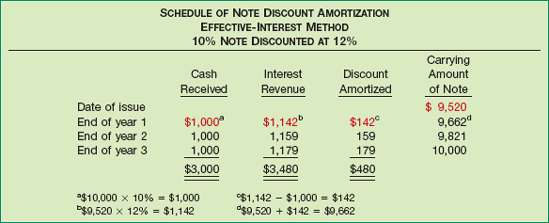

Morgan then amortizes the discount and recognizes interest revenue annually using the effective-interest method. Illustration 7-14 shows the three-year discount amortization and interest revenue schedule.

On the date of issue, the note has a present value of $9,520. Its unamortized discount—additional interest revenue spread over the three-year life of the note—is $480.

At the end of year 1, Morgan receives $1,000 in cash. But its interest revenue is $1,142 ($9,520 × 12%). The difference between $1,000 and $1,142 is the amortized discount, $142. Morgan records receipt of the annual interest and amortization of the discount for the first year as follows (amounts per amortization schedule).

The carrying amount of the note is now $9,662 ($9,520 + $142). Morgan repeats this process until the end of year 3.

When the present value exceeds the face value, the note is exchanged at a premium. Companies record the premium on a note receivable as a debit and amortize it using the effective-interest method over the life of the note as annual reductions in the amount of interest revenue recognized.

When a note is received in exchange for property, goods, or services in a bargained transaction entered into at arm's length, the stated interest rate is presumed to be fair unless:

No interest rate is stated, or

The stated interest rate is unreasonable, or

The face amount of the note is materially different from the current cash sales price for the same or similar items or from the current market value of the debt instrument. [4]

In these circumstances, the company measures the present value of the note by the fair value of the property, goods, or services or by an amount that reasonably approximates the market value of the note.

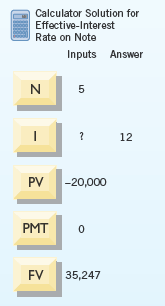

To illustrate, Oasis Development Co. sold a corner lot to Rusty Pelican as a restaurant site. Oasis accepted in exchange a five-year note having a maturity value of $35,247 and no stated interest rate. The land originally cost Oasis $14,000. At the date of sale the land had a fair market value of $20,000. Given the criterion above, Oasis uses the fair market value of the land, $20,000, as the present value of the note. Oasis therefore records the sale as:

Oasis amortizes the discount to interest revenue over the five-year life of the note using the effective-interest method.

In note transactions, other factors involved in the exchange, such as the fair value of the property, goods, or services, determine the effective or real interest rate. But, if a company cannot determine that fair value, and if the note has no ready market, determining the present value of the note is more difficult. To estimate the present value of a note under such circumstances, the company must approximate an applicable interest rate that may differ from the stated interest rate. This process of interest-rate approximation is called imputation. The resulting interest rate is called an imputed interest rate.

The prevailing rates for similar instruments, from issuers with similar credit ratings, affect the choice of a rate. Restrictive covenants, collateral, payment schedule, and the existing prime interest rate also impact the choice. A company determines the imputed interest rate when it receives the note. It ignores any subsequent changes in prevailing interest rates.

Like accounts receivable, companies record and report short-term notes receivable at their net realizable value—that is, at their face amount less all necessary allowances. The primary notes receivable allowance account is Allowance for Doubtful Accounts. The computations and estimations involved in valuing short-term notes receivable and in recording bad debt expense and the related allowance exactly parallel that for trade accounts receivable. Companies estimate the amount of uncollectibles by using either a percentage of sales revenue or an analysis of the receivables.

Long-term note receivables involve additional estimation problems. For example, the value of a note receivable can change significantly over time from its original cost. That is, with the passage of time, historical numbers become less and less relevant. As discussed in earlier chapters (2, 5, 6), the FASB requires that for financial instruments such as receivables, companies disclose not only their cost but also their fair value in the notes to the financial statements.

Fair Value Option. Recently the Board has taken the additional step of giving companies the option to use fair value as the basis of measurement in the financial statements. [5] The Board believes that fair value measurement for financial instruments provides more relevant and understandable information than historical cost. It considers fair value to be more relevant because it reflects the current cash equivalent value of financial instruments. As a result, companies now have the option to record fair value in their accounts for most financial instruments, including receivables.

If companies choose the fair value option, the receivables are recorded at fair value, with unrealized holding gains or losses reported as part of net income. An unrealized holding gain or loss is the net change in the fair value of the receivable from one period to another, exclusive of interest revenue recognized but not recorded. As a result, the company reports the receivable at fair value each reporting date. In addition, it reports the change in value as part of net income.

Companies may elect to use the fair value option at the time the financial instrument is originally recognized or when some event triggers a new basis of accounting (such as when a business acquisition occurs). If a company elects the fair value option for a financial instrument, it must continue to use fair value measurement for that instrument until the company no longer owns this instrument. If the company does not elect the fair value option for a given financial instrument at the date of recognition, it may not use this option on that specific instrument in subsequent periods.

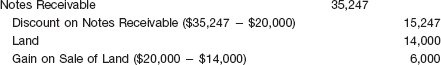

Recording Fair Value Option. Assume that Escobar Company has notes receivable that have a fair value of $810,000 and a carrying amount of $620,000. Escobar decides on December 31, 2010, to use the fair value option for these receivables. This is the first valuation of these recently acquired receivables. Having elected to use the fair value option, Escobar must value these receivables at fair value in all subsequent periods in which it holds these receivables. Similarly, if Escobar elects not to use the fair value option, it must use its carrying amount for all future periods.

When using the fair value option, Escobar reports the receivables at fair value, with any unrealized holding gains and losses reported as part of net income. The unrealized holding gain is the difference between the fair value and the carrying amount at December 31, 2010, which for Escobar is $190,000 ($810,000 − $620,000). At December 31, 2010, Escobar makes an adjusting entry to record the increase in value of Notes Receivable and to record the unrealized holding gain, as follows.

Escobar adds the difference between fair value and the cost of the notes receivable to arrive at the fair value reported on the balance sheet. In subsequent periods, the company will report any change in fair value as an unrealized holding gain or loss. For example, if at December 31, 2011, the fair value of the notes receivable is $800,000, Escobar would recognize an unrealized holding loss of $10,000 ($810,000 − $800,000) and reduce the Notes Receivable account.

Impairments. A note receivable may become impaired. A note receivable is considered impaired when it is probable that the creditor will be unable to collect all amounts due (both principal and interest) according to the contractual terms of the receivable. In this case, a loss is recorded for the amount of the impairment. Appendix 7B further discusses impairments of receivables.

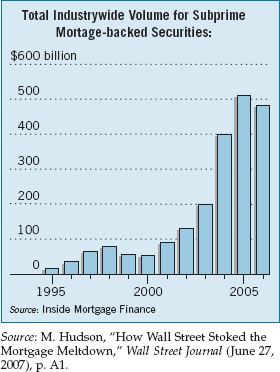

The massive write-downs that financial firms are posting have begun to spur a backlash among some investors and executives, who are blaming accounting rules for exaggerating the losses and are seeking new, more forgiving ways to value investments.

The rules—which last made headlines back in the Enron era—require companies to value many of the securities they hold at whatever price prevails in the market, no matter how sharply those prices swing.

Some analysts and executives argue this triggers a domino effect. The market falls, forcing banks to take write-offs, pushing the market lower, causing more write-offs. Companies like AIG argue that their write-downs may never actually result in a true charge to the company. It's a sore point because companies feel they are being forced to take big financial hits on holdings that they have no intention of actually selling at current prices.

Companies believe they are strong enough to simply keep the holdings in their portfolios until the crisis passes. Forcing companies to value securities based on what they would fetch if sold today "is an attempt to apply liquidation accounting to a going concern," says one analyst. Bob Herz, FASB chairman, acknowledges the difficulty but notes, "you tell me what a better answer is.... Is just pretending that things aren't decreasing in value a better answer? Should you just let everybody say they think it's going to recover?"

Others who favor the use of market values say that for all its imperfections, market value also imposes discipline on companies. "It forces you to realistically confront what's happening to you much quicker, so it plays a useful purpose," said Sen. Jack Reed (D., R.I.), a member of the Senate banking committee.

Japan stands out as an example of how ignoring problems can lead to years-long stagnation. "Look at Japan, where they ignored write-downs at all their financial institutions when loans went bad," said Jeff Mahoney, general counsel at the Council for Institutional Investors.

In addition, companies don't always have the luxury of waiting out a storm until assets recover the long-term value that executives believe exists. Sometimes market crises force their hands. Freddie Mac, for instance, sold $45 billion of assets last fall to help the company meet regulatory capital requirements.

Source: Adapted from David Reilly, "Wave of Write-Offs Rattles Market: Accounting Rules Blasted as Dow Falls; A $600 Billon Toll?" Wall Street Journal (March 1, 2008), p. Al.

In the normal course of events, companies collect accounts and notes receivable when due and then remove them from the books. However, the growing size and significance of credit sales and receivables has led to changes in this "normal course of events." In order to accelerate the receipt of cash from receivables, the owner may transfer accounts or notes receivables to another company for cash.

There are various reasons for this early transfer. First, for competitive reasons, providing sales financing for customers is virtually mandatory in many industries. In the sale of durable goods, such as automobiles, trucks, industrial and farm equipment, computers, and appliances, most sales are on an installment contract basis. Many major companies in these industries have created wholly-owned subsidiaries specializing in receivables financing. For example, General Motors Corp. has General Motors Acceptance Corp. (GMAC), and John Deere has John Deere Credit.

Second, the holder may sell receivables because money is tight and access to normal credit is unavailable or too expensive. Also, a firm may sell its receivables, instead of borrowing, to avoid violating existing lending agreements.

Finally, billing and collection of receivables are often time-consuming and costly. Credit card companies such as MasterCard, Visa, American Express, Diners Club, Discover, and others take over the collection process and provide merchants with immediate cash.

Conversely, some purchasers of receivables buy them to obtain the legal protection of ownership rights afforded a purchaser of assets versus the lesser rights afforded a secured creditor. In addition, banks and other lending institutions may need to purchase receivables because of legal lending limits. That is, they cannot make any additional loans but they can buy receivables and charge a fee for this service.

The transfer of receivables to a third party for cash happens in one of two ways:

A company often uses receivables as collateral in a borrowing transaction. In fact, a creditor often requires that the debtor designate (assign) or pledge[88] receivables as security for the loan. If the loan is not paid when due, the creditor can convert the collateral to cash—that is, collect the receivables.

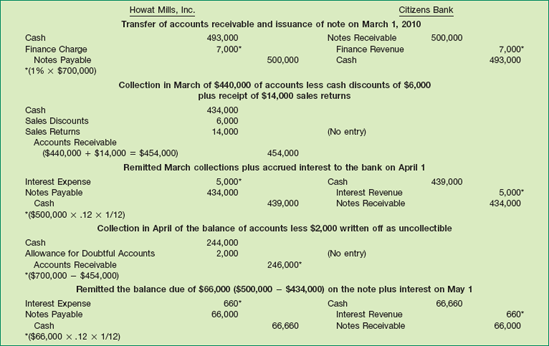

To illustrate, on March 1, 2010, Howat Mills, Inc. provides (assigns) $700,000 of its accounts receivable to Citizens Bank as collateral for a $500,000 note. Howat Mills continues to collect the accounts receivable; the account debtors are not notified of the arrangement. Citizens Bank assesses a finance charge of 1 percent of the accounts receivable and interest on the note of 12 percent. Howat Mills makes monthly payments to the bank for all cash it collects on the receivables. Illustration 7-15 shows the entries for the secured borrowing for Howatt Mills and Citizens Bank.

In addition to recording the collection of receivables, Howat Mills must recognize all discounts, returns and allowances, and bad debts. Each month Howat Mills uses the proceeds from the collection of the accounts receivable to retire the note obligation. In addition, it pays interest on the note.[89]

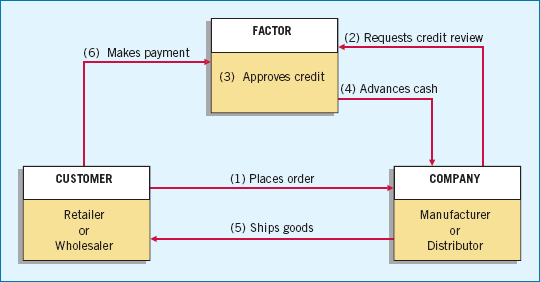

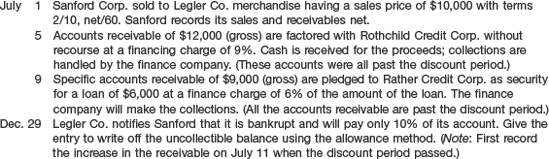

Sales of receivables have increased substantially in recent years. A common type is a sale to a factor. Factors are finance companies or banks that buy receivables from businesses for a fee and then collect the remittances directly from the customers. Factoring receivables is traditionally associated with the textile, apparel, footwear, furniture, and home furnishing industries.[90] Illustration 7-16 shows a typical factoring arrangement.

A recent phenomenon in the sale (transfer) of receivables is securitization. Securitization takes a pool of assets such as credit card receivables, mortgage receivables, or car loan receivables, and sells shares in these pools of interest and principal payments. This, in effect, creates securities backed by these pools of assets. Virtually every asset with a payment stream and a long-term payment history is a candidate for securitization.

What are the differences between factoring and securitization? Factoring usually involves sale to only one company, fees are high, the quality of the receivables is low, and the seller afterward does not service the receivables. In a securitization, many investors are involved, margins are tight, the receivables are of generally higher quality, and the seller usually continues to service the receivables.

In either a factoring or a securitization transaction, a company sells receivables on either a without recourse or a with recourse basis.[91]

When buying receivables without recourse, the purchaser assumes the risk of collectibility and absorbs any credit losses. The transfer of accounts receivable in a nonrecourse transaction is an outright sale of the receivables both in form (transfer of title) and substance (transfer of control). In nonrecourse transactions, as in any sale of assets, the seller debits Cash for the proceeds and credits Accounts Receivable for the face value of the receivables. The seller recognizes the difference, reduced by any provision for probable adjustments (discounts, returns, allowances, etc.), as a Loss on the Sale of Receivables. The seller uses a Due from Factor account (reported as a receivable) to account for the proceeds retained by the factor to cover probable sales discounts, sales returns, and sales allowances.

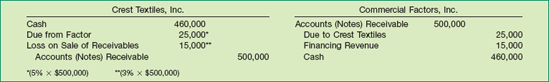

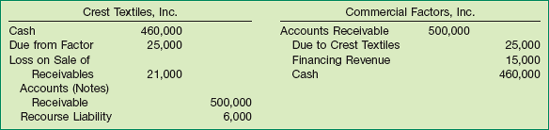

To illustrate, Crest Textiles, Inc. factors $500,000 of accounts receivable with Commercial Factors, Inc., on a without recourse basis. Crest Textiles transfers the receivable records to Commercial Factors, which will receive the collections. Commercial Factors assesses a finance charge of 3 percent of the amount of accounts receivable and retains an amount equal to 5 percent of the accounts receivable (for probable adjustments). Crest Textiles and Commercial Factors make the following journal entries for the receivables transferred without recourse.

In recognition of the sale of receivables, Crest Textiles records a loss of $15,000. The factor's net income will be the difference between the financing revenue of $15,000 and the amount of any uncollectible receivables.

For receivables sold with recourse, the seller guarantees payment to the purchaser in the event the debtor fails to pay. To record this type of transaction, the seller uses a financial components approach, because the seller has a continuing involvement with the receivable. Values are now assigned to such components as the recourse provision, servicing rights, and agreement to reacquire. In this approach, each party to the sale only recognizes the assets and liabilities that it controls after the sale.

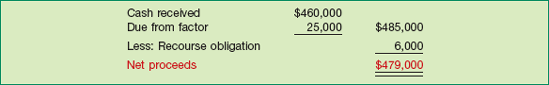

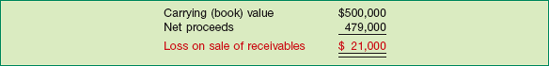

To illustrate, assume the same information as in Illustration 7-17 for Crest Textiles and for Commercial Factors, except that Crest Textiles sold the receivables on a with-recourse basis. Crest Textiles determines that this recourse obligation has a fair value of $6,000. To determine the loss on the sale of the receivables, Crest Textiles computes the net proceeds from the sale as follows.

Net proceeds are cash or other assets received in a sale less any liabilities incurred. Crest Textiles then computes the loss as follows.

Illustration 7-20 shows the journal entries for both Crest Textiles and Commercial Factors for the receivables sold with recourse.

In this case, Crest Textiles recognizes a loss of $21,000. In addition, it records a liability of $6,000 to indicate the probable payment to Commercial Factors for uncollectible receivables. If Commercial Factors collects all the receivables, Crest Textiles eliminates its recourse liability and increases income. Commercial Factors' net income is the financing revenue of $15,000. It will have no bad debts related to these receivables.

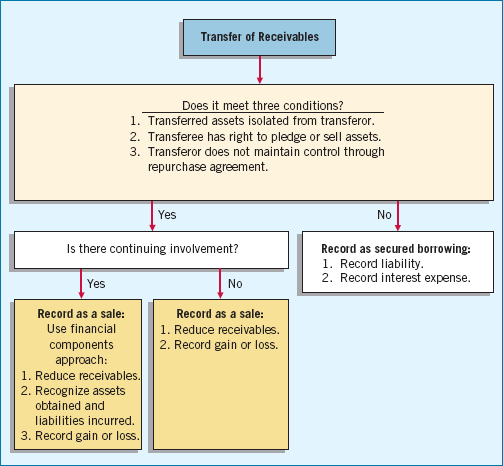

The FASB concluded that a sale occurs only if the seller surrenders control of the receivables to the buyer. The following three conditions must be met before a company can record a sale:

The transferred asset has been isolated from the transferor (put beyond reach of the transferor and its creditors).

The transferees have obtained the right to pledge or exchange either the transferred assets or beneficial interests in the transferred assets.

The transferor does not maintain effective control over the transferred assets through an agreement to repurchase or redeem them before their maturity.

If the three conditions are met, a sale occurs. Otherwise, the transferor should record the transfer as a secured borrowing. If sale accounting is appropriate, a company must still consider assets obtained and liabilities incurred in the transaction. Illustration 7-21 (page 342) shows the rules of accounting for transfers of receivables. As it shows, if there is continuing involvement in a sale transaction, a company must record the assets obtained and liabilities incurred.

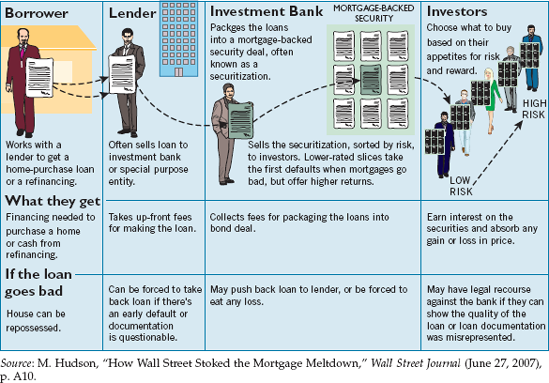

It used to be that lenders of mortgages and other types of debt securities carried them on their books as a loan receivable. This approach had some limitations. First, lenders were limited to the amount of loans they could make based on their deposit base (and therefore fee revenue was limited). Second, if the loans went bad, lenders had to record a loss. But thanks to Wall Street, many lenders learned how to package these loans together and sell them to an entity such as a trust (often referred to as a special-purpose entity) and record a gain on the sale. Everyone was happy—for a while.

Here is how it works: The lender sells the loans to the trust, reports a gain, and generally earns fees for servicing the debt. It also takes the loan off its balance sheet and therefore has more flexibility to get more loans. The trust raises the money to buy these loans by selling some type of interest-bearing security to the investing public. The trust (usually created by the lender) is fine because it matches up the cash flows it pays the lender with the cash flows it receives from investors who purchase the interest-bearing securities. These investors are happy because they earn a return they believe is excellent, given the risk they take.

There are two big problems with these arrangements. First, as indicated in our discussion in the text, the lender has to make sure it does not keep control; otherwise it cannot sell the receivable and receive gain on sale treatment. Unfortunately, the accounting rules are loose enough that lenders are able to argue that they do not have control in most cases. Second, lenders began to realize that lending to subprime borrowers could be very profitable. They focused on these customers because the bank earns a fee for origination of the loan, sells the loans for a gain, and earns servicing revenue—a triple bump to the bottom line. However, when the housing market collapsed, the subprime borrowers could not repay their loans, and the credit markets collapsed. The result was a credit crisis.

So, who loses? Investors, for starters. These investors did not understand the risks they were taking. (And we should note that many of these investors were other financial institutions, who should have known better.) How about the lenders? They claim they sold the loan, and it is no longer their responsibility. But many investors are not ready to let lenders off the hook. They are arguing that in many of these sales the lender must take back loans that defaulted unusually fast or contained mistakes or fraud (bogus appraisals, inflated borrower incomes, and other misrepresentations). For example, Countrywide Financial Corp., the largest mortgage lender in the United States, indicated that its liability for such claims increased by nearly $600 million from March 31, 2007, to March 31, 2008.

The moral of the story is that accounting matters. Lenders have strong incentives to want to report upfront gains on sales of loans. But in most cases these gains should never have been booked. If the accounting did not permit gain on sale treatment, the lender would have to keep the loan on its balance sheet. Under these conditions, lenders would be much less likely to lend so much money to individuals with poor credit ratings.

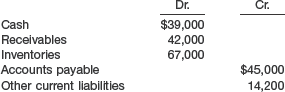

The general rules in classifying receivables are:

Segregate the different types of receivables that a company possesses, if material.

Appropriately offset the valuation accounts against the proper receivable accounts.

Determine that receivables classified in the current assets section will be converted into cash within the year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer.

Disclose any loss contingencies that exist on the receivables.

Disclose any receivables designated or pledged as collateral.

Disclose all significant concentrations of credit risk arising from receivables.[92]

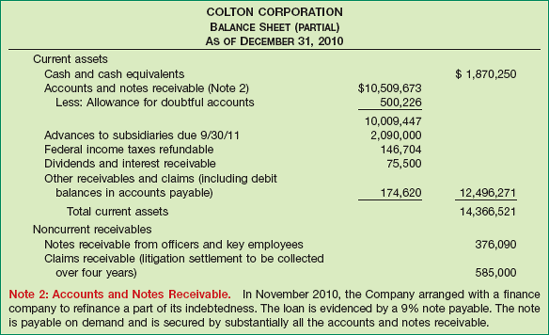

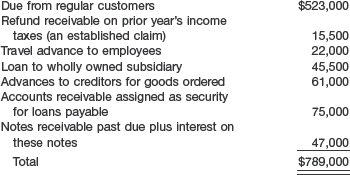

The assets sections of Colton Corporation's balance sheet in Illustration 7-22 show many of the disclosures required for receivables.

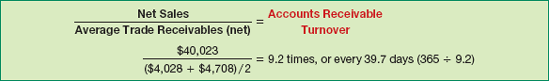

Analysts frequently compute financial ratios to evaluate the liquidity of a company's accounts receivable. To assess the liquidity of the receivables, they use the receivables turnover ratio. This ratio measures the number of times, on average, a company collects receivables during the period. The ratio is computed by dividing net sales by average (net) receivables outstanding during the year. Theoretically, the numerator should include only net credit sales, but this information is frequently unavailable. However, if the relative amounts of credit and cash sales remain fairly constant, the trend indicated by the ratio will still be valid. Barring significant seasonal factors, average receivables outstanding can be computed from the beginning and ending balances of net trade receivables.

To illustrate, Best Buy reported 2008 net sales of $40,023 million, its beginning and ending accounts receivable balances were $4,028 million and $4,708 million, respectively. Illustration 7-23 shows the computation of its accounts receivables turnover ratio.

This information[93] shows how successful the company is in collecting its outstanding receivables. If possible, an aging schedule should also be prepared to help determine how long receivables have been outstanding. A satisfactory receivables turnover may have resulted because certain receivables were collected quickly though others have been outstanding for a relatively long period. An aging schedule would reveal such patterns.

Often the receivables turnover is transformed to days to collect accounts receivable or days outstanding—an average collection period. In this case, 9.2 is divided into 365 days, resulting in 39.7 days. Companies frequently use the average collection period to assess the effectiveness of a company's credit and collection policies. The general rule is that the average collection period should not greatly exceed the credit term period. That is, if customers are given a 60-day period for payment, then the average collection period should not be too much in excess of 60 days.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are very similar in accounting for cash and receivables. AIS No. 1 ("Presentation of Financial Statements") is the only standard that discusses issues specifically related to cash. IFRS No. 7 ("Financial Instruments: Disclosures") and IAS No. 39 ("Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement") are the two international standards that address issues related to financial instruments and more specifically receivables.

The accounting and reporting related to cash is essentially the same under both iGAAP and U.S. GAAP. In addition, the definition used for cash equivalents is the same.

The basic accounting and reporting issues related to recognition and measurement of receivables, such as the use of allowance accounts, how to record trade and sales discounts, use of percentage-of-sales and receivables methods, pledging, and factoring are essentially the same between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP.

Although iGAAP implies that receivables with different characteristics should be reported separately, there is no standard that mandates this segregation. In addition, there is no specific standard related to pledging, assignment, or factoring.

Like the FASB, the IASB has worked to implement fair value measurement for all financial instruments, but both Boards have faced bitter opposition from various factions. As a consequence, the Boards have adopted a piecemeal approach in which disclosure of fair value information in the notes is the first step. The second step is the fair value option which permits companies to record fair values in the financial statements. Both Boards have indicated that they believe all financial instruments should be recorded and reported at fair value.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP standards on the fair value option are similar but not identical. The international standard related to the fair value option is subject to certain qualifying criteria not in the U.S. standard. In addition, there is some difference in the financial instruments covered.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP differ in the criteria used to derecognize a receivable. iGAAP is a combination of an approach focused on risks and rewards and loss of control. U.S. GAAP uses loss of control as the primary criterion. In addition, iGAAP permits partial derecognition; U.S. GAAP does not.

In the accounting for loans and receivables, iGAAP permits the reversal of impairment losses, with the reversal limited to the asset's amortized cost before the impairment. To illustrate, Zirbel Company has a loan receivable with a carrying value of $10,000 at December 31, 2010. On January 2, 2011, the borrower declares bankruptcy, and Zirbel estimates that it will collect only one-half of the loan balance. Zirbel makes the following entry to record the impairment.

On January 10, 2012, Zirbel learns that the customer has emerged from bankruptcy. Zirbel now estimates that all but $1,000 will be repaid on the loan. Under iGAAP, Zirbel records this reversal as follows.

Zirbel reports the recovery in 2012 income. Under U.S. GAAP, reversal of an impairment is not permitted. Rather, the balance on the loan after the impairment becomes the new basis for the loan.

It appears likely that the question of recording fair values for financial instruments will continue to be an important issue to resolve as the Boards work toward convergence. Both the IASB and the FASB have indicated that they believe that financial statements would be more transparent and understandable if companies recorded and reported all financial instruments at fair value.

The fair value option for recording financial instruments such as receivables is an important step in moving closer to fair value recording. However, we hope that this is only an intermediate step and that the Boards continue to work toward the adoption of comprehensive fair value accounting for financial instruments.

Ideally, companies should measure receivables in terms of their present value—that is, the discounted value of the cash to be received in the future. The profession specifically excludes from the present-value considerations receivables arising from normal business transactions that are due in customary trade terms within approximately one year.

Cash is the asset most susceptible to improper diversion and use. Management faces two problems in accounting for cash transactions: (1) to establish proper controls to prevent any unauthorized transactions by officers or employees, and (2) to provide information necessary to properly manage cash on hand and cash transactions. Yet even with sophisticated control devices, errors can and do happen. For example, the Wall Street Journal ran a story entitled "A $7.8 Million Error Has a Happy Ending for a Horrified Bank." The story described how Manufacturers Hanover Trust Co. mistakenly overpaid about $7.8 million in cash dividends to its stockholders. (As implied in the headline, most stockholders returned the monies.)

To safeguard cash and to ensure the accuracy of the accounting records for cash, companies need effective internal control over cash. Provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 call for enhanced efforts to increase the quality of internal control (for cash and other assets). Such efforts are expected to result in improved financial reporting. In this appendix, we discuss some of the basic control issues related to cash.

To obtain desired control objectives, a company can vary the number and location of banks and the types of bank accounts. For large companies operating in multiple locations, the location of bank accounts can be important. Establishing collection accounts in strategic locations can accelerate the flow of cash into the company by shortening the time between a customer's mailing of a payment and the company's use of the cash. Multiple collection centers generally reduce the size of a company's collection float. This is the difference between the amount on deposit according to the company's records and the amount of collected cash according to the bank record.

Large, multilocation companies frequently use lockbox accounts to collect in cities with heavy customer billing. The company rents a local post office box and authorizes a local bank to pick up the remittances mailed to that box number. The bank empties the box at least once a day and immediately credits the company's account for collections. The greatest advantage of a lockbox is that it accelerates the availability of collected cash. Generally, in a lockbox arrangement the bank microfilms the checks for record purposes and provides the company with a deposit slip, a list of collections, and any customer correspondence. Thus, a lockbox system improves the control over cash and accelerates collection of cash. If the income generated from accelerating the receipt of funds exceeds the cost of the lockbox system, then it is a worthwhile undertaking.

The general checking account is the principal bank account in most companies and frequently the only bank account in small businesses. A company deposits in and disburses cash from this account. A company cycles all transactions through it. For example, a company deposits from and disburses to all other bank accounts through the general checking account.

Companies use imprest bank accounts to make a specific amount of cash available for a limited purpose. The account acts as a clearing account for a large volume of checks or for a specific type of check. To clear a specific and intended amount through the imprest account, a company transfers that amount from the general checking account or other source. Companies often use imprest bank accounts for disbursing payroll checks, dividends, commissions, bonuses, confidential expenses (e.g., officers' salaries), and travel expenses.

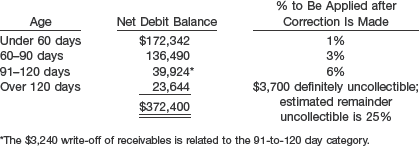

Almost every company finds it necessary to pay small amounts for miscellaneous expenses such as taxi fares, minor office supplies, and employee's lunches. Disbursements by check for such items is often impractical, yet some control over them is important. A simple method of obtaining reasonable control, while adhering to the rule of disbursement by check, is the imprest system for petty cash disbursements. This is how the system works:

The company designates a petty cash custodian, and gives the custodian a small amount of currency from which to make payments. It records transfer of funds to petty cash as:

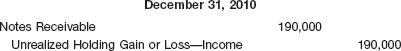

The petty cash custodian obtains signed receipts from each individual to whom he or she pays cash, attaching evidence of the disbursement to the petty cash receipt. Petty cash transactions are not recorded until the fund is reimbursed; someone other than the petty cash custodian records those entries.

When the supply of cash runs low, the custodian presents to the controller or accounts payable cashier a request for reimbursement supported by the petty cash receipts and other disbursement evidence. The custodian receives a company check to replenish the fund. At this point, the company records transactions based on petty cash receipts.

If the company decides that the amount of cash in the petty cash fund is excessive, it lowers the fund balance as follows.

Subsequent to establishment, a company makes entries to the Petty Cash account only to increase or decrease the size of the fund.

A company uses a Cash Over and Short account when the petty cash fund fails to prove out. That is, an error occurs such as incorrect change, overpayment of expense, or lost receipt. If cash proves out short (i.e., the sum of the receipts and cash in the fund is less than the imprest amount), the company debits the shortage to the Cash Over and Short account. If cash proves out over, it credits the overage to Cash Over and Short. The company closes Cash Over and Short only at the end of the year. It generally shows Cash Over and Short on the income statement as an "Other expense or revenue."

There are usually expense items in the fund except immediately after reimbursement. Therefore, to maintain accurate financial statements, a company must reimburse the funds at the end of each accounting period and also when nearly depleted.

Under the imprest system the petty cash custodian is responsible at all times for the amount of the fund on hand either as cash or in the form of signed receipts. These receipts provide the evidence required by the disbursing officer to issue a reimbursement check. Further, a company follows two additional procedures to obtain more complete control over the petty cash fund:

A superior of the petty cash custodian makes surprise counts of the fund from time to time to determine that a satisfactory accounting of the fund has occurred.

The company cancels or mutilates petty cash receipts after they have been submitted for reimbursement, so that they cannot be used to secure a second reimbursement.

Not only must a company safeguard cash receipts and cash disbursements through internal control measures, but it must also protect the cash on hand and in banks. Because receipts become cash on hand and disbursements are made from cash in banks, adequate control of receipts and disbursements is part of the protection of cash balances, along with certain other procedures.

Physical protection of cash is so elementary a necessity that it requires little discussion. A company should make every effort to minimize the cash on hand in the office. It should only have on hand a petty cash fund, the current day's receipts, and perhaps funds for making change. Insofar as possible, it should keep these funds in a vault, safe, or locked cash drawer. The company should transmit intact each day's receipts to the bank as soon as practicable. Accurately stating the amount of available cash both in internal management reports and in external financial statements is also extremely important.

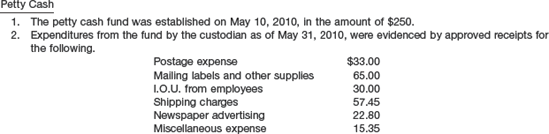

Every company has a record of cash received, disbursed, and the balance. Because of the many cash transactions, however, errors or omissions may occur in keeping this record. Therefore, a company must periodically prove the balance shown in the general ledger. It can count cash actually present in the office—petty cash, change funds, and undeposited receipts—for comparison with the company records. For cash on deposit, a company prepares a bank reconciliation—a reconciliation of the company's record and the bank's record of the company's cash.

At the end of each calendar month the bank supplies each customer with a bank statement (a copy of the bank's account with the customer) together with the customer's checks that the bank paid during the month.[94] If neither the bank nor the customer made any errors, if all deposits made and all checks drawn by the customer reached the bank within the same month, and if no unusual transactions occurred that affected either the company's or the bank's record of cash, the balance of cash reported by the bank to the customer equals that shown in the customer's own records. This condition seldom occurs for one or more of the reconciling items presented on the next page. Hence, a company expects differences between its record of cash and the bank's record. Therefore, it must reconcile the two to determine the nature of the differences between the two amounts.

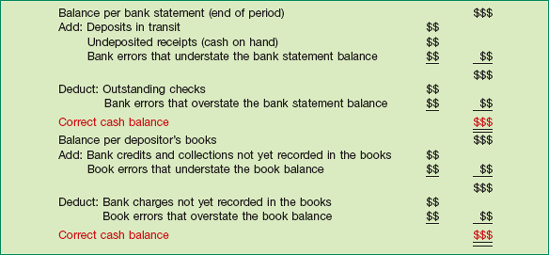

A bank reconciliation is a schedule explaining any differences between the bank's and the company's records of cash. If the difference results only from transactions not yet recorded by the bank, the company's record of cash is considered correct. But, if some part of the difference arises from other items, either the bank or the company must adjust its records.

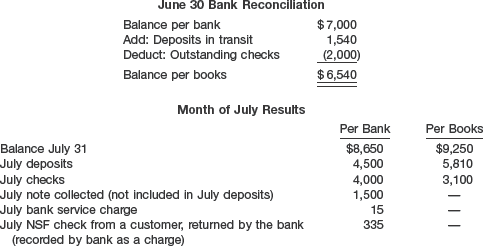

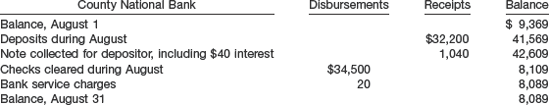

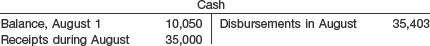

A company may prepare two forms of a bank reconciliation. One form reconciles from the bank statement balance to the book balance or vice versa. The other form reconciles both the bank balance and the book balance to a correct cash balance. Most companies use this latter form. Illustration 7A-1 shows a sample of that form and its common reconciling items.

This form of reconciliation consists of two sections: (1) "Balance per bank statement" and (2) "Balance per depositor's books." Both sections end with the same "Correct cash balance." The correct cash balance is the amount to which the books must be adjusted and is the amount reported on the balance sheet. Companies prepare adjusting journal entries for all the addition and deduction items appearing in the "Balance per depositor's books" section. Companies should immediately call to the bank's attention any errors attributable to it.

To illustrate, Nugget Mining Company's books show a cash balance at the Denver National Bank on November 30, 2010, of $20,502. The bank statement covering the month of November shows an ending balance of $22,190. An examination of Nugget's accounting records and November bank statement identified the following reconciling items.

A deposit of $3,680 that Nugget mailed November 30 does not appear on the bank statement.

Checks written in November but not charged to the November bank statement are:

Check #7327

$ 150

#7348

4,820

#7349

31

Nugget has not yet recorded the $600 of interest collected by the bank November 20 on Sequoia Co. bonds held by the bank for Nugget.

Bank service charges of $18 are not yet recorded on Nugget's books.

The bank returned one of Nugget's customer's checks for $220 with the bank statement, marked "NSF." The bank treated this bad check as a disbursement.

Nugget discovered that it incorrectly recorded check #7322, written in November for $131 in payment of an account payable, as $311.

A check for Nugent Oil Co. in the amount of $175 that the bank incorrectly charged to Nugget accompanied the statement.

Nugget reconciled the bank and book balances to the correct cash balance of $21,044 as shown in Illustration 7A-2.

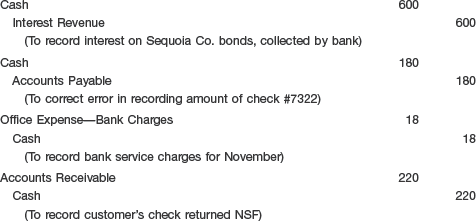

The journal entries required to adjust and correct Nugget's books in early December 2010 are taken from the items in the "Balance per books" section and are as follows.

After posting the entries, Nugget's cash account will have a balance of $21,044. Nugget should return the Nugent Oil Co. check to Denver National Bank, informing the bank of the error.

Rebecca Cobos overdrew her checking account at a Bank of America branch in Los Angeles. When she could not immediately repay the bank, it not only closed her account but also had her, in effect, banned for five years from opening a checking account at most other banks.

Bank of America did so by reporting the 23-year-old university secretary to ChexSystems, a national database to which 80 percent of banks in the country subscribe. Once lodged in ChexSystems, your name automatically stays there for five years, whether your offense was bouncing a check or two or committing serious fraud. The large majority of banks using ChexSystems reject any checking-account applicant they find in the database.

Maintained by a unit of the check-printing company Deluxe Corp., ChexSystems currently has about seven million names on file. Bank officials and executives of the unit, called eFund, defend the database as a valuable weapon in the battle against fraud and high-risk customers. And there is no denying that many of those who end up in the database have been financially careless, or worse.

Source: Paul Beckett, "It's Not in the Mail," Wall Street Journal (August 1, 2000), p. A1.

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVE FOR APPENDIX 7A

Companies continually evaluate their receivables to determine their ultimate collectibility. As discussed in the chapter, the FASB considers the collectibility of receivables a loss contingency. Thus, the allowance method is appropriate in situations where it is probable that an asset has been impaired and the amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated. Generally, companies start with historical loss rates and modify these rates for changes in economic conditions that could affect a borrower's ability to repay the loan. The discussion in the chapter assumed use of this approach to determine the amount of bad debts to be recorded for a period.

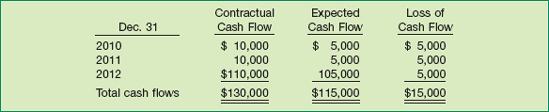

However, for long-term receivables such as loans that are identified as impaired, companies perform an additional impairment evaluation.[95] GAAP has specific rules for measurement and reporting of these impairments. These rules relate to determining the value of these loans and how much loss to recognize if the holder of the loans plans to keep them in hope that the market will recover. More complex rules arise when these loans are sold as part of the securitization process, especially when the original terms of the notes are modified.[96]