After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

The essential characteristics of accounting are: (1) the identification, measurement, and communication of financial information about (2) economic entities to (3) interested parties. Financial accounting is the process that culminates in the preparation of financial reports on the enterprise for use by both internal and external parties. Users of these financial reports include investors, creditors, managers, unions, and government agencies. In contrast, managerial accounting is the process of identifying, measuring, analyzing, and communicating financial information needed by management to plan, control, and evaluate a company's operations.

Financial statements are the principal means through which a company communicates its financial information to those outside it. These statements provide a company's history quantified in money terms. The financial statements most frequently provided are (1) the balance sheet, (2) the income statement, (3) the statement of cash flows, and (4) the statement of owners' or stockholders' equity. Note disclosures are an integral part of each financial statement.

Some financial information is better provided, or can be provided only, by means of financial reporting other than formal financial statements. Examples include the president's letter or supplementary schedules in the corporate annual report, prospectuses, reports filed with government agencies, news releases, management's forecasts, and social or environmental impact statements. Companies may need to provide such information because of authoritative pronouncement, regulatory rule, or custom. Or they may supply it because management wishes to disclose it voluntarily.

In this textbook, we focus on the development of two types of financial information: (1) the basic financial statements and (2) related disclosures.

Resources are limited. As a result, people try to conserve them and ensure that they are used effectively. Efficient use of resources often determines whether a business thrives. This fact places a substantial burden on the accounting profession.

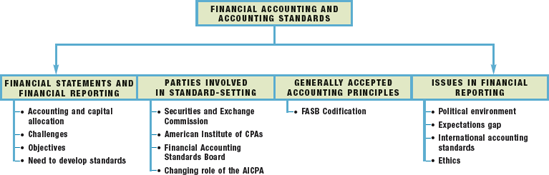

Accountants must measure performance accurately and fairly on a timely basis, so that the right managers and companies are able to attract investment capital. For example, relevant and reliable financial information allows investors and creditors to compare the income and assets employed by such companies as IBM, McDonald's, Microsoft, and Ford. Because these users can assess the relative return and risks associated with investment opportunities, they channel resources more effectively. Illustration 1-1 shows how this process of capital allocation works.

An effective process of capital allocation is critical to a healthy economy. It promotes productivity, encourages innovation, and provides an efficient and liquid market for buying and selling securities and obtaining and granting credit.[1] Unreliable and irrelevant information leads to poor capital allocation, which adversely affects the securities markets.

"It's the accounting." That's what many investors seem to be saying these days. Even the slightest hint of any accounting irregularity at a company leads to a subsequent pounding of the company's stock price. For example, the Wall Street Journal has run the following headlines related to accounting and its effects on the economy.

It now has become clear that investors must trust the accounting numbers or they will abandon the market and put their resources elsewhere. With investor uncertainty, the cost of capital increases for companies who need additional resources. In short, relevant and reliable financial information is necessary for markets to be efficient.

As indicated in the opening story, much is right about financial reporting in the United States. One reason for this success is that our financial statements and related disclosures capture and organize financial information in a useful and reliable fashion. However, much still needs to be done. For example, if we move to the year 2020 and look back at financial reporting today, we might read the following:

Nonfinancial Measurements. Financial reports failed to provide some key performance measures widely used by management, such as customer satisfaction indexes, backlog information, and reject rates on goods purchased.

Forward-looking Information. Financial reports failed to provide forward-looking information needed by present and potential investors and creditors. One individual noted that financial statements in 2008 should have started with the phrase, "Once upon a time," to signify their use of historical cost and accumulation of past events.

Soft Assets. Financial reports focused on hard assets (inventory, plant assets) but failed to provide much information about a company's soft assets (intangibles). The best assets are often intangible. Consider Microsoft's know-how and market dominance, Dell's unique marketing setup and well-trained employees, and J. Crew's brand image.

Timeliness. Companies only prepared financial statements quarterly, and provided audited financials annually. Little to no real-time financial statement information was available.

We believe each of these challenges must be met for the accounting profession to provide the type of information needed for an efficient capital allocation process. We are confident that changes will occur, based on these positive signs:

Already some companies voluntarily disclose information deemed relevant to investors. Often such information is nonfinancial. For example, regional banking companies, such as BankOne Corp., Fifth Third Bancorp, and Sun Trust Banks, now include data on loan growth, credit quality, fee income, operating efficiency, capital management, and management strategy.

Initially, companies used the World Wide Web to provide limited financial data. Now, most companies publish their annual reports in several formats on the Web. The most innovative companies offer sections of their annual reports in a format that the user can readily manipulate, such as in an Excel spreadsheet format. Companies also format their financial reports using extensible business reporting language (XBRL), which permits quicker and lower cost access to companies' financial information.

More accounting standards now require the recording or disclosing of fair value information. For example, companies either record investments in stocks and bonds, debt obligations, and derivatives at fair value or companies show information related to fair values in the notes to the financial statements.

Changes in these directions will enhance the relevance of financial reporting and provide useful information to financial statement readers.

To establish a foundation for financial accounting and reporting, the accounting profession identified a set of objectives of financial reporting by business enterprises. Financial reporting should provide information that:

Is useful to present and potential investors and creditors and other users in making rational investment, credit, and similar decisions. The information should be comprehensible to those who have a reasonable understanding of business and economic activities and are willing to study the information with reasonable diligence.

Helps present and potential investors, creditors, and other users assess the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of prospective cash receipts from dividends or interest and the proceeds from the sale, redemption, or maturity of securities or loans. Since investors' and creditors' cash flows are related to enterprise cash flows, financial reporting should provide information to help investors, creditors, and others assess the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of prospective net cash inflows to the related enterprise.

Clearly portrays the economic resources of an enterprise, the claims to those resources (obligations of the enterprise to transfer resources to other entities and owners' equity), and the effects of transactions, events, and circumstances that change its resources and claims to those resources.[2]

In brief, the objectives of financial reporting are to provide information that is (1) useful in investment and credit decisions, (2) useful in assessing cash flow prospects, and (3) about company resources, claims to those resources, and changes in them.

The emphasis on "assessing cash flow prospects" does not mean that the cash basis is preferred over the accrual basis of accounting. That is not the case. Information based on accrual accounting generally better indicates a company's present and continuing ability to generate favorable cash flows than does information limited to the financial effects of cash receipts and payments.[3]

Recall from your first accounting course the objective of accrual-basis accounting: It ensures that a company records events that change its financial statements in the periods in which the events occur, rather than only in the periods in which it receives or pays cash. Using the accrual basis to determine net income means that a company recognizes revenues when it earns them rather than when it receives cash. Similarly, it recognizes expenses when it incurs them rather than when it pays them. Under accrual accounting, a company generally recognizes revenues when it makes sales. The company can then relate the revenues to the economic environment of the period in which they occurred. Over the long run, trends in revenues and expenses are generally more meaningful than trends in cash receipts and disbursements.

The main controversy in setting accounting standards is, "Whose rules should we play by, and what should they be?" The answer is not immediately clear. Users of financial accounting statements have both coinciding and conflicting needs for information of various types. To meet these needs, and to satisfy the fiduciary[4] reporting responsibility of management, companies prepare a single set of general-purpose financial statements. Users expect these statements to present fairly, clearly, and completely the company's financial operations.

The accounting profession has attempted to develop a set of standards that are generally accepted and universally practiced. Otherwise, each enterprise would have to develop its own standards. Further, readers of financial statements would have to familiarize themselves with every company's peculiar accounting and reporting practices. It would be almost impossible to prepare statements that could be compared.

This common set of standards and procedures is called generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The term "generally accepted" means either that an authoritative accounting rule-making body has established a principle of reporting in a given area or that over time a given practice has been accepted as appropriate because of its universal application.[5] Although principles and practices continue to provoke both debate and criticism, most members of the financial community recognize them as the standards that over time have proven to be most useful. We present a more extensive discussion of what constitutes GAAP later in this chapter.

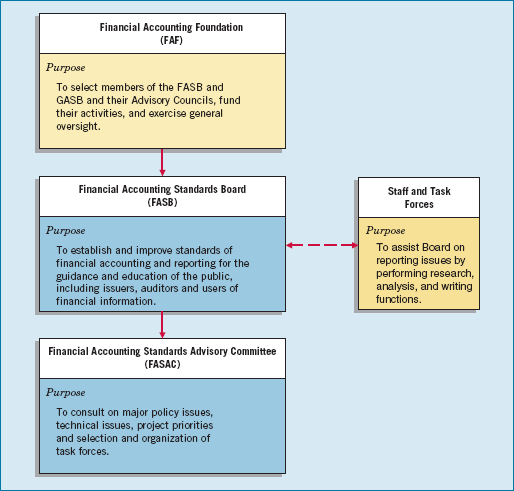

Three organizations are instrumental in the development of financial accounting standards (GAAP) in the United States:

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA)

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)

External financial reporting and auditing developed in tandem with the growth of the industrial economy and its capital markets. However, when the stock market crashed in 1929 and the nation's economy plunged into the Great Depression, there were calls for increased government regulation of business generally, and especially financial institutions and the stock market.

As a result of these events, the federal government established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to help develop and standardize financial information presented to stockholders. The SEC is a federal agency. It administers the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and several other acts. Most companies that issue securities to the public or are listed on a stock exchange are required to file audited financial statements with the SEC. In addition, the SEC has broad powers to prescribe, in whatever detail it desires, the accounting practices and standards to be employed by companies that fall within its jurisdiction. The SEC currently exercises oversight over 12,000 companies that are listed on the major exchanges (e.g., the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq).

At the time the SEC was created, no group—public or private—issued accounting standards. The SEC encouraged the creation of a private standard-setting body because it believed that the private sector had the appropriate resources and talent to achieve this daunting task. As a result, accounting standards have developed in the private sector either through the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) or the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

The SEC has affirmed its support for the FASB by indicating that financial statements conforming to standards set by the FASB are presumed to have substantial authoritative support. In short, the SEC requires registrants to adhere to GAAP. In addition, the SEC indicated in its reports to Congress that "it continues to believe that the initiative for establishing and improving accounting standards should remain in the private sector, subject to Commission oversight."

The SEC's partnership with the private sector works well. The SEC acts with remarkable restraint in the area of developing accounting standards. Generally, the SEC relies on the FASB to develop accounting standards.

The SEC's involvement in the development of accounting standards varies. In some cases, the SEC rejects a standard proposed by the private sector. In other cases, the SEC prods the private sector into taking quicker action on certain reporting problems, such as accounting for investments in debt and equity securities and the reporting of derivative instruments. In still other situations, the SEC communicates problems to the FASB, responds to FASB exposure drafts, and provides the FASB with counsel and advice upon request.

The SEC's mandate is to establish accounting principles. The private sector, therefore, must listen carefully to the views of the SEC. In some sense the private sector is the formulator and the implementor of the standards.[6] However, when the private sector fails to address accounting problems as quickly as the SEC would like, the partnership between the SEC and the private sector can be strained. This occurred in the deliberations on the accounting for business combinations and intangible assets. It is also highlighted by concerns over the accounting for off-balance sheet special-purpose entities, highlighted in the failure of Enron and more recently, the subprime crises that led to the failure of IndyMac Bank.

As we indicated earlier, companies listed on a stock exchange must submit their financial statements to the SEC. If the SEC believes that an accounting or disclosure irregularity exists regarding the form or content of the financial statements, it sends a deficiency letter to the company. Companies usually resolve these deficiency letters quickly. If disagreement continues, the SEC may issue a "stop order," which prevents the registrant from issuing or trading securities on the exchanges. The Department of Justice may also file criminal charges for violations of certain laws. The SEC process, private sector initiatives, and civil and criminal litigation help to ensure the integrity of financial reporting for public companies.

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), which is the national professional organization of practicing Certified Public Accountants (CPAs), has been an important contributor to the development of GAAP. Various committees and boards established since the founding of the AICPA have contributed to this effort.

At the urging of the SEC, the AICPA appointed the Committee on Accounting Procedure in 1939. The Committee on Accounting Procedure (CAP), composed of practicing CPAs, issued 51 Accounting Research Bulletins during the years 1939 to 1959. These bulletins dealt with a variety of accounting problems. But this problem-by-problem approach failed to provide the needed structured body of accounting principles. In response, in 1959 the AICPA created the Accounting Principles Board.

The major purposes of the Accounting Principles Board (APB) were to (1) advance the written expression of accounting principles, (2) determine appropriate practices, and (3) narrow the areas of difference and inconsistency in practice. To achieve these objectives, the APB's mission was twofold: to develop an overall conceptual framework to assist in the resolution of problems as they become evident and to substantively research individual issues before the AICPA issued pronouncements. The Board's 18 to 21 members, selected primarily from public accounting, also included representatives from industry and academia. The Board's official pronouncements, called APB Opinions, were intended to be based mainly on research studies and be supported by reason and analysis. Between its inception in 1959 and its dissolution in 1973, the APB issued 31 opinions.

Unfortunately, the APB came under fire early, charged with lack of productivity and failing to act promptly to correct alleged accounting abuses. Later the APB tackled numerous thorny accounting issues, only to meet a buzz saw of opposition from industry and CPA firms. It also ran into occasional governmental interference. In 1971 the accounting profession's leaders, anxious to avoid governmental rule-making, appointed a Study Group on Establishment of Accounting Principles. Commonly known as the Wheat Committee for its chair Francis Wheat, this group examined the organization and operation of the APB and determined the necessary changes to attain better results. The Study Group submitted its recommendations to the AICPA Council in the spring of 1972. The AICPA Council adopted the recommendations in total, and implemented them by early 1973.

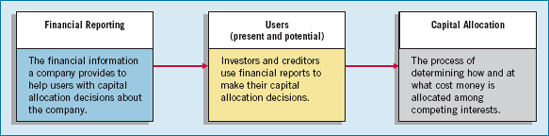

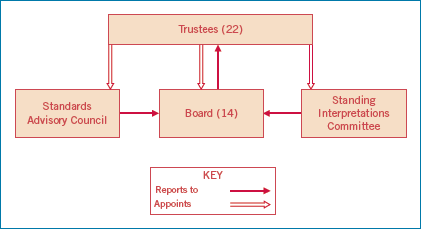

The Wheat Committee's recommendations resulted in the demise of the APB and the creation of a new standard-setting structure composed of three organizations—the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF), the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), and the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council (FASAC). The Financial Accounting Foundation selects the members of the FASB and the Advisory Council, funds their activities, and generally oversees the FASB's activities.

The major operating organization in this three-part structure is the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Its mission is to establish and improve standards of financial accounting and reporting for the guidance and education of the public, which includes issuers, auditors, and users of financial information. The expectations of success and support for the new FASB relied on several significant differences between it and its predecessor, the APB:

Smaller Membership. The FASB consists of five members, replacing the relatively large 18-member APB.

Full-time, Remunerated Membership. FASB members are well-paid, full-time members appointed for renewable 5-year terms. The APB members volunteered their part-time work.

Greater Autonomy. The APB was a senior committee of the AICPA. The FASB is not part of any single professional organization. It is appointed by and answerable only to the Financial Accounting Foundation.

Increased Independence. APB members retained their private positions with firms, companies, or institutions. FASB members must sever all such ties.

Broader Representation. All APB members were required to be CPAs and members of the AICPA. Currently, it is not necessary to be a CPA to be a member of the FASB.

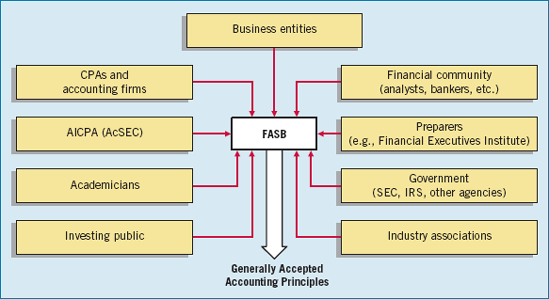

In addition to research help from its own staff, the FASB relies on the expertise of various task force groups formed for various projects and on the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council (FASAC). FASAC consults with the FASB on major policy and technical issues and also helps select task force members. Illustration 1-2 shows the current organizational structure for the development of financial reporting standards.

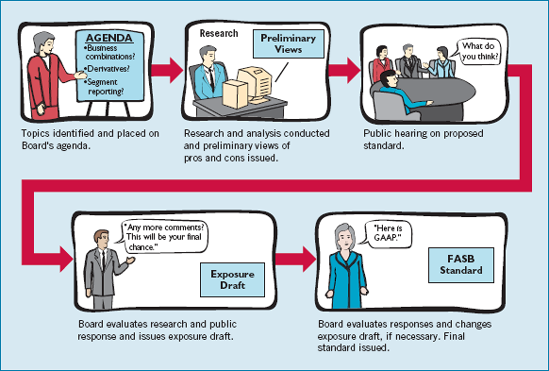

In establishing financial accounting standards, the FASB relies on two basic premises: (1) The FASB should be responsive to the needs and viewpoints of the entire economic community, not just the public accounting profession. (2) It should operate in full view of the public through a "due process" system that gives interested persons ample opportunity to make their views known. To ensure the achievement of these goals, the FASB follows specific steps to develop a typical FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, as Illustration 1-3 shows.

The passage of a new FASB Standards Statement requires the support of three of the five Board members. FASB Statements are considered GAAP and thereby binding in practice. All ARBs and APB Opinions implemented by 1973 (when the FASB formed) continue to be effective until amended or superseded by FASB pronouncements. In recognition of possible misconceptions of the term "principles," the FASB uses the term financial accounting standards in its pronouncements.

The FASB issues three major types of pronouncements:

Standards, Interpretations, and Staff Positions. Financial accounting standards issued by the FASB are considered generally accepted accounting principles. In addition, the FASB also issues interpretations that modify or extend existing standards. Interpretations have the same authority, and require the same votes for passage, as standards. The APB also issued interpretations of APB Opinions. Both types of interpretations are now considered authoritative for purposes of determining GAAP. Finally, the FASB issues staff positions, which provide interpretive guidance and also minor amendments to standards and interpretations. These staff positions have the same authority as standards and interpretations. The Board also has issued FASB Technical Bulletins, which provide timely guidance on selected issues; staff positions are now used in lieu of technical bulletins. Since replacing the APB, the FASB has issued over 160 standards, 48 interpretations, and over 50 staff positions.

Financial Accounting Concepts. As part of a long-range effort to move away from the problem-by-problem approach, the FASB in November 1978 issued the first in a series of Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts as part of its conceptual framework project. (See list at the back of the book.) The series sets forth fundamental objectives and concepts that the Board uses in developing future standards of financial accounting and reporting. The Board intends to form a cohesive set of interrelated concepts—a conceptual framework—that will serve as tools for solving existing and emerging problems in a consistent manner. Unlike a Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, a Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts does not establish GAAP. Concepts statements, however, pass through the same due process system (preliminary views, public hearing, exposure draft, etc.) as do standards statements.

Emerging Issues Task Force Statements. In 1984 the FASB created the Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF). The EITF is comprised of representatives from CPA firms and financial statement preparers. Observers from the SEC and AICPA also attend EITF meetings. The purpose of the task force is to reach a consensus on how to account for new and unusual financial transactions that may potentially create differing financial reporting practices. Examples include accounting for pension plan terminations, revenue from barter transactions by Internet companies, and excessive amounts paid to takeover specialists. The EITF also provided timely guidance for the reporting of the losses arising from the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

We cannot overestimate the importance of the EITF. In one year, for example, the task force examined 61 emerging financial reporting issues and arrived at a consensus on approximately 75 percent of them. The FASB reviews and approves all EITF consensuses. And the SEC indicated that it will view consensus solutions as preferred accounting. Further, it requires persuasive justification for departing from them.

The EITF helps the FASB in many ways. For example, emerging issues often attract public attention. If not resolved quickly, they can lead to financial crises and scandal. They can also undercut public confidence in current reporting practices. The next step, possible governmental intervention, would threaten the continuance of standard-setting in the private sector. The EITF identifies controversial accounting problems as they arise. The EITF determines whether it can quickly resolve them, or whether to involve the FASB in solving them. In essence, it becomes a "problem filter" for the FASB. Thus, the FASB will hopefully work on more pervasive long-term problems, while the EITF deals with short-term emerging issues.

For several decades the AICPA provided leadership in developing accounting principles and rules. More than any other organization, it regulated the accounting profession, and developed and enforced accounting practice. When the FASB replaced the Accounting Principles Board, the AICPA established the Accounting Standards Executive Committee (AcSEC) as the committee authorized to speak for the AICPA in the area of financial accounting and reporting. It does so through various written communications:

Audit and Accounting Guides summarize the accounting practices of specific industries and provide specific guidance on matters not addressed by the FASB. Examples are accounting for casinos, airlines, colleges and universities, banks, insurance companies, and many others.

Statements of Position (SOP) provide guidance on financial reporting topics until the FASB sets standards on the issue in question. SOPs may update, revise, and clarify audit and accounting guides or provide free-standing guidance.

Practice Bulletins indicate AcSEC's views on narrow financial reporting issues not considered by the FASB.

The role of the AICPA in standard-setting has diminished. The FASB and the AICPA agree that the AICPA and AcSEC no longer will issue authoritative accounting guidance for public companies. Furthermore, while the AICPA has been the leader in developing auditing standards through its Auditing Standards Board, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board to oversee the development of auditing standards. The AICPA will continue to develop and grade the CPA examination, which is administered in all 50 states.

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) have substantial authoritative support. The AICPA's Code of Professional Conduct requires that members prepare financial statements in accordance with GAAP. Specifically, Rule 203 of this Code prohibits a member from expressing an unqualified opinion on financial statements that contain a material departure from generally accepted accounting principles.

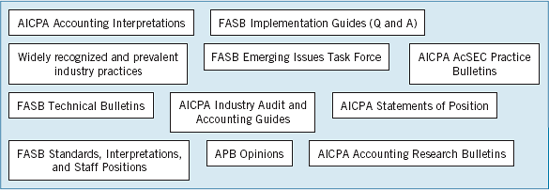

What is GAAP? The major sources of GAAP come from the organizations discussed earlier in this chapter. It is composed of a mixture of over 2,000 documents that have developed over the last 60 years or so. It includes such items as FASB Standards, Interpretations, and Staff Positions; APB Opinions; and AICPA Research Bulletins. Illustration 1-4 highlights the many different types of documents that comprise GAAP.

As might be expected, the documents that comprise GAAP vary in format, completeness, and structure. In some cases, these documents are inconsistent and difficult to interpret. As a result, financial statement preparers sometimes are not sure whether they have the right GAAP; determining what is authoritative and what is not becomes difficult.

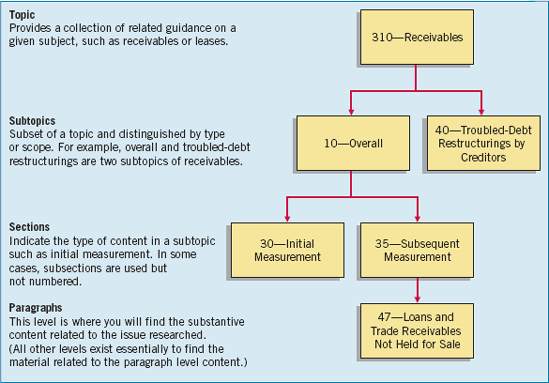

In response to these concerns, the FASB developed the Financial Accounting Standards Board Accounting Standards Codification (or more simply, "the Codification"). The FASB's primary goal in developing the Codification is to provide in one place all the authoritative literature related to a particular topic. This will simplify user access to all authoritative U.S. generally accepted accounting principles. The Codification changes the way GAAP is documented, presented, and updated. It explains what GAAP is and eliminates nonessential information such as redundant document summaries, basis for conclusions sections, and historical content. In short, the Codification is a major restructuring of accounting and reporting standards. Its purpose is to integrate and synthesize existing GAAP—not to create new GAAP. It creates one level of GAAP, which is considered authoritative. All other accounting literature is considered nonauthoritative.[7]

To provide easy access to this Codification, the FASB also developed the Financial Accounting Standards Board Codification Research System (CRS). CRS is an online real-time database that provides easy access to the Codification. The Codification and the related CRS provide a topically organized structure, subdivided into topic, subtopics, sections, and paragraphs, using a numerical index system.

For purposes of referencing authoritative GAAP material in this textbook, we will use the Codification framework. Here is an example of how the Codification framework is cited, using Receivables as the example. The purpose of the search shown below is to determine GAAP for accounting for loans and trade receivables not held for sale subsequent to initial measurement.

Topic | Go to FASB ASC 310 to access the Receivables topic. |

Subtopics | Go to FASB ASC 310-10 to access the Overall Subtopic of the Topic 310. |

Sections | Go to FASB ASC 310-10-35 to access the Subsequent Measurement Section of the Subtopic 310-10. |

Paragraph | Go to FASB ASC 310-10-35-47 to access the Loans and Trade Receivables not Held for Sale paragraph of Section 310-10-35. |

Illustration 1-5 shows the Codification framework graphically.

What happens if the Codification does not cover a certain type of transaction or event? In that case, other accounting literature should be considered, such as FASB Concept Statements, international financial reporting standards, and other professional literature. This will happen only rarely.

The expectations for the Codification are high. It is hoped that the Codification will enable users to better understand what GAAP is. As a result, the time to research accounting issues and the risk of noncompliance with GAAP will be reduced, sometimes substantially. In addition, the electronic web-based format will make updating easier, which will help users stay current with GAAP.[8]

For individuals (like you) attempting to learn GAAP, the Codification will be invaluable. It is an outstanding effort by the profession to streamline and simplify how to determine what GAAP is, which will lead to better financial accounting and reporting. We provide references to the Codification throughout this textbook, using a numbering system. For example, a bracket with a number, such as [1], indicates that the citation to the FASB Codification can be found in the FASB Codification section at the end of the chapter (immediately before the assignment materials).

Should the accounting profession have principles-based standards or rules-based standards? Critics of the profession today say that over the past three decades, standard-setters have moved away from broad accounting principles aimed at ensuring that companies' financial statements are fairly presented.

Instead, these critics say, standard-setters have moved toward drafting voluminous rules that, if technically followed in "check-box" fashion, may shield auditors and companies from legal liability. That has resulted in companies creating complex capital structures that comply with GAAP but hide billions of dollars of debt and other obligations. To add fuel to the fire, the chief accountant of the enforcement division of the SEC recently noted, "One can violate SEC laws and still comply with GAAP."

In short, what he is saying is that it is not enough just to check the boxes. You have to exercise judgment in applying GAAP to achieve high-quality reporting.

Sources: Adapted from S. Liesman, "SEC Accounting Cop's Warning: Playing by the Rules May Not Head Off Fraud Issues," Wall Street Journal (February 12, 2002), p. C7. See also "Study Pursuant to Section 108(d) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 on the Adoption by the United States Financial Reporting System of a Principles-Based Accounting System," SEC (July 25, 2003).

Since the implementation of GAAP may affect many interests, much discussion occurs about who should develop GAAP and to whom it should apply. We discuss some of the major issues below.

User groups are possibly the most powerful force influencing the development of GAAP. User groups consist of those most interested in or affected by accounting rules. Like lobbyists in our state and national capitals, user groups play a significant role. GAAP is as much a product of political action as it is of careful logic or empirical findings. User groups may want particular economic events accounted for or reported in a particular way, and they fight hard to get what they want. They know that the most effective way to influence GAAP is to participate in the formulation of these rules or to try to influence or persuade the formulator of them.

These user groups often target the FASB, to pressure it to influence changes in the existing rules and the development of new ones.[9] In fact, these pressures have been multiplying. Some influential groups demand that the accounting profession act more quickly and decisively to solve its problems. Other groups resist such action, preferring to implement change more slowly, if at all. Illustration 1-6 shows the various user groups that apply pressure.

Should there be politics in establishing GAAP for financial accounting and reporting? Why not? We have politics at home; at school; at the fraternity, sorority, and dormitory; at the office; at church, temple, and mosque. Politics is everywhere. GAAP is part of the real world, and it cannot escape politics and political pressures.

Investors generally ignore an accounting change, except when it substantially affects net income. Goodwill provides a good example. Under previous GAAP, companies with goodwill charged it to revenues over time. Under new rules, companies no longer have to write off this cost. The effect on the bottom line for some companies is substantial. For example, assuming no goodwill amortization, International Paper estimates an income increase of 21 percent, Johnson Controls 16 percent, and Pepsi Bottling Group 30 percent.

Some believe this change will increase their stock's attractiveness. Others argue that it should have no effect because the write-off is a mere bookkeeping charge. Still others argue that the change has no effect on cash flows, but that investors will perceive the company to be more profitable, and therefore a good buy in the marketplace. In short, the numbers have consequences. What do you think?

That is not to say that politics in establishing GAAP is a negative force. Considering the economic consequences[10] of many accounting rules, special interest groups should vocalize their reactions to proposed rules. What the Board should not do is issue pronouncements that are primarily politically motivated. While paying attention to its constituencies, the Board should base GAAP on sound research and a conceptual framework that has its foundation in economic reality.

Accounting scandals at companies like Enron, Cendant, Sunbeam, Rite-Aid, Xerox, and WorldCom have attracted the attention of Congress. As a result, it enacted legislation—the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. This law increases the resources for the SEC to combat fraud and curb poor reporting practices.[11] And the SEC has increased its policing efforts, approving new auditor independence rules and materiality guidelines for financial reporting. In addition, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act introduces sweeping changes to the institutional structure of the accounting profession. The following are some of the key provisions of the legislation.

Establishes an oversight board, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), for accounting practices. The PCAOB has oversight and enforcement authority and establishes auditing, quality control, and independence standards and rules.

Implements stronger independence rules for auditors. Audit partners, for example, are required to rotate every five years and auditors are prohibited from offering certain types of consulting services to corporate clients.

Requires CEOs and CFOs to personally certify that financial statements and disclosures are accurate and complete and requires CEOs and CFOs to forfeit bonuses and profits when there is an accounting restatement.

Requires audit committees to be comprised of independent members and members with financial expertise.

Requires codes of ethics for senior financial officers.

In addition, Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires public companies to attest to the effectiveness of their internal controls over financial reporting. Internal controls are a system of checks and balances designed to prevent and detect fraud and errors. Most companies have these systems in place, but many have never completely documented them. Companies are finding that it is a costly process but perhaps badly needed. Already intense examination of internal controls has found lingering problems in the way companies operate. Recently, 424 companies reported deficiencies in internal control.[12] Many problems involved closing the books, revenue recognition deficiencies, reconciling accounts, or dealing with inventory. SunTrust Bank, for example, fired three officers after discovering errors in how the company calculates its allowance for bad debts. And Visteon, a car parts supplier, said it found problems recording and managing receivables from its largest customer, Ford Motor.

Will these changes be enough? The expectations gap—what the public thinks accountants should do and what accountants think they can do—is difficult to close. Due to the number of fraudulent reporting cases, some question whether the profession is doing enough. Although the profession can argue rightfully that accounting cannot be responsible for every financial catastrophe, it must continue to strive to meet the needs of society. However, efforts to meet these needs will become more costly to society. The development of a highly transparent, clear, and reliable system will require considerable resources.

A former Secretary of the Treasury, Lawrence Summers, indicated that the single most important innovation shaping the capital markets was the idea of generally accepted accounting principles. He went on to say that we need something similar internationally.

We believe that the Secretary is right. Relevant and reliable financial information is a necessity for viable capital markets. Unfortunately, companies outside the United States often prepare financial statements using standards different from U.S. GAAP. As a result, international companies such as Coca-Cola, Microsoft, and IBM have to develop financial information in different ways. Beyond the additional costs these companies incur, users of the financial statements often must understand at least two sets of GAAP. (Understanding one set is hard enough!) It is not surprising therefore that there is a growing demand for one set of high-quality international standards.

Presently, there are two sets of rules accepted for international use—U.S. GAAP and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), also known as iGAAP, issued by the London-based International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). U.S. companies that list overseas are still permitted to use U.S. GAAP, and foreign companies listed on U.S. exchanges are permitted to use iGAAP. As you will learn, there are many similarities between U.S. GAAP and iGAAP.

Already over 100 countries use iGAAP, and the European Union now requires all listed companies in Europe (over 7,000 companies) to use it. Recently the U.S. SEC proposed that it will allow some U.S. companies to adopt iGAAP as early as 2009. The SEC also laid out a roadmap by which all U.S. companies will be required to use iGAAP by 2016. Most parties recognize that global markets will best be served if only one set of GAAP is used. For example, the FASB and the IASB formalized their commitment to the convergence of U.S. GAAP and iGAAP by issuing a memorandum of understanding (often referred to as the Norwalk agreement). The two boards agreed to use their best efforts to:

make their existing financial reporting standards fully compatible as soon as practicable, and

coordinate their future work programs to ensure that once achieved, compatibility is maintained.

As a result of this agreement, the two boards identified a number of short-term and long-term projects that would lead to convergence. For example, one short-term project was for the FASB to issue a rule that permits a fair value option for financial instruments. This rule was issued in 2007, and now the FASB and the IASB follow the same accounting in this area. Conversely, the IASB is presently working on a rule related to borrowing costs, in an effort to make it consistent with U.S. GAAP. Long-term convergence projects relate to such issues as revenue recognition, the conceptual framework, and research and development costs.

Because convergence is such an important issue, we provide throughout this textbook a summary page on international accounting called Convergence Corner. This feature will help you understand the changes that are taking place in the financial reporting area as we move to one set of international GAAP. In addition, throughout the textbook we provide in the margins International Insights to help you understand the international reporting environment. Also, Appendix 24B has an expanded discussion of international accounting.

Robert Sack, a noted commentator on the subject of accounting ethics, observed, "Based on my experience, new graduates tend to be idealistic ... thank goodness for that! Still it is very dangerous to think that your armor is all in place and say to yourself, 'I would have never given in to that.' The pressures don't explode on us; they build, and we often don't recognize them until they have us."

These observations are particularly appropriate for anyone entering the business world. In accounting, as in other areas of business, we frequently encounter ethical dilemmas. Some of these dilemmas are simple and easy to resolve. However, many are not, requiring difficult choices among allowable alternatives.

Companies that concentrate on "maximizing the bottom line," "facing the challenges of competition," and "stressing short-term results" place accountants in an environment of conflict and pressure. Basic questions such as, "Is this way of communicating financial information good or bad?" "Is it right or wrong? "What should I do in the circumstance?" cannot always be answered by simply adhering to GAAP or following the rules of the profession. Technical competence is not enough when encountering ethical decisions.

Doing the right thing is not always easy or obvious. The pressures "to bend the rules," "to play the game," "to just ignore it" can be considerable. For example, "Will my decision affect my job performance negatively?", "Will my superiors be upset?", "Will my colleagues be unhappy with me?" are often questions business people face in making a tough ethical decision. The decision is more difficult because there is no comprehensive ethical system to provide guidelines.

Time, job, client, personal, and peer pressures can complicate the process of ethical sensitivity and selection among alternatives. Throughout this textbook, we present ethical considerations to help sensitize you to the type of situations you may encounter in the performance of your professional responsibility.

Bob Herz, FASB chairman, believes that there are three fundamental considerations the FASB must keep in mind in its rule-making activities: (1) improvement in financial reporting, (2) simplification of the accounting literature and the rule-making process, and (3) international convergence. These are notable objectives, and the Board is making good progress on all three dimensions. Issues such as off-balance-sheet financing, measurement of fair values, enhanced criteria for revenue recognition, and stock option accounting are examples of where the Board has exerted leadership. Improvements in financial reporting should follow.

Also, the Board is making it easier to understand what GAAP is. GAAP has been contained in a number of different documents. The lack of a single source makes it difficult to access and understand generally accepted principles. As discussed earlier, the Codification now organizes existing GAAP by accounting topic regardless of its source (FASB Statements, APB Opinions, and so on). The codified standards are then considered to be GAAP and to be authoritative. All other literature will be considered nonauthoritative.

Finally, international convergence is underway. Some projects already are completed and differences eliminated. Many more are on the drawing board. It appears to be only a matter of time until we will have one set of global GAAP that will be established by the IASB. The profession has many challenges, but it has responded in a timely, comprehensive, and effective manner.

Most agree that there is a need for one set of international accounting standards. Here is why:

Multinational corporations. Today companies view the entire world as their market. For example, Coca-Cola, Intel, and McDonald's generate more than 50 percent of their sales outside the United States, and many foreign companies find their largest market to be the United States.

Mergers and acquisitions. The mergers that led to international giants DaimlerChrysler and Vodafone/Mannesmann suggest that we will see even more such mergers in the future.

Information technology. As communication barriers continue to topple through advances in technology, companies and individuals in different countries and markets are becoming comfortable buying and selling goods and services from one another.

Financial markets. Financial markets are some of the most significant international markets today. Whether it is currency, equity securities (stocks), bonds, or derivatives, there are active markets throughout the world trading these types of instruments.

iGAAP includes the standards, referred to as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), developed by the IASB. The predecessor to the IASB issued International Accounting Standards (IAS). Both IFRS and IAS are considered iGAAP.

The fact that there are differences between U.S. GAAP and iGAAP should not be surprising because standard-setters have developed standards in response to different user needs. In some countries, the primary users of financial statements are private investors; in others, the primary users are tax authorities or central government planners. In the United States, investors and creditors have driven accounting-standard formulation.

iGAAP tends to be simpler and less stringent in its accounting and disclosure requirements. U.S. GAAP is more detailed. This difference in approach has resulted in a debate about the merits of "principle-based" versus "rule-based" standards.

Regulators have recently eliminated the need for foreign companies that trade shares in U.S. markets to reconcile their accounting with U.S. GAAP.

The IASB is a relatively new organization (formed in 2001). As a result, it has looked to the United States to determine the structure it should follow in establishing iGAAP. Thus, the standard-setting structure internationally is very similar to the standard-setting structure in the United States. Presented below is a chart of the international standard-setting structure.

Both the IASB and the FASB are hard at work developing standards that will lead to the elimination of major differences in the way certain transactions are accounted for and reported. In fact, the IASB has stated that no new major standards will become effective until 2009. The major reason for this policy is to provide companies time to translate and implement iGAAP into practice.

Much has happened in a very short period of time in the international accounting environment. It now appears likely that in a fairly short period of time, U.S. companies will be using iGAAP instead of GAAP in the United States.

Differentiate broadly between financial accounting and managerial accounting.

Differentiate between "financial statements" and "financial reporting."

How does accounting help the capital allocation process?

What are some of the major challenges facing the accounting profession?

What are the major objectives of financial reporting?

Of what value is a common set of standards in financial accounting and reporting?

What is the likely limitation of "general-purpose financial statements"?

In what way is the Securities and Exchange Commission concerned about and supportive of accounting principles and standards?

What was the Committee on Accounting Procedure, and what were its accomplishments and failings?

For what purposes did the AICPA in 1959 create the Accounting Principles Board?

Distinguish among Accounting Research Bulletins, Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board, and Statements of the Financial Accounting Standards Board.

If you had to explain or define "generally accepted accounting principles or standards," what essential characteristics would you include in your explanation?

In what ways was it felt that the statements issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board would carry greater weight than the opinions issued by the Accounting Principles Board?

How are FASB preliminary views and FASB exposure drafts related to FASB "statements"?

Distinguish between FASB "statements of financial accounting standards" and FASB "statements of financial accounting concepts."

What is Rule 203 of the Code of Professional Conduct?

Rank from the most authoritative to the least authoritative, the following three items: FASB Technical Bulletins, AICPA Practice Bulletins, and FASB Standards.

The chairman of the FASB at one time noted that "the flow of standards can only be slowed if (1) producers focus less on quarterly earnings per share and tax benefits and more on quality products, and (2) accountants and lawyers rely less on rules and law and more on professional judgment and conduct." Explain his comment.

What is the purpose of FASB Staff Positions?

Explain the role of the Emerging Issues Task Force in establishing generally accepted accounting principles.

What is the difference between the Codification and the Codification Research System?

What are the primary advantages of having a Codification of generally accepted accounting principles?

What are the sources of pressure that change and influence the development of GAAP?

Some individuals have indicated that the FASB must be cognizant of the economic consequences of its pronouncements. What is meant by "economic consequences"? What dangers exist if politics play too much of a role in the development of GAAP?

If you were given complete authority in the matter, how would you propose that GAAP should be developed and enforced?

One writer recently noted that 99.4 percent of all companies prepare statements that are in accordance with GAAP. Why then is there such concern about fraudulent financial reporting?

What is the "expectations gap"? What is the profession doing to try to close this gap?

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act was enacted to combat fraud and curb poor reporting practices. What are some key provisions of this legislation?

How are financial accountants challenged in their work to make ethical decisions? Is technical mastery of GAAP not sufficient to the practice of financial accounting?

CA1-1 (Financial Accounting) Omar Morena has recently completed his first year of studying accounting. His instructor for next semester has indicated that the primary focus will be the area of financial accounting.

Instructions

Differentiate between financial accounting and managerial accounting.

One part of financial accounting involves the preparation of financial statements. What are the financial statements most frequently provided?

What is the difference between financial statements and financial reporting?

CA1-2 (Objectives of Financial Reporting) Karen Sepan, a recent graduate of the local state university, is presently employed by a large manufacturing company. She has been asked by Jose Martinez, controller, to prepare the company's response to a current Preliminary Views published by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Sepan knows that the FASB has issued seven Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts, and she believes that these concept statements could be used to support the company's response to the Preliminary Views. She has prepared a rough draft of the response citing Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1, "Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises."

Instructions

Identify the three objectives of financial reporting as presented in Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1 (SFAC No. 1).

Describe the level of sophistication expected of the users of financial information by SFAC No. 1.

(CMA adapted)

CA1-3 (Accounting Numbers and the Environment) Hardly a day goes by without an article appearing on the crises affecting many of our financial institutions in the United States. It is estimated that the savings and loan (S&L) debacle of the 1980s, for example, ended up costing $500 billion ($2,000 for every man, woman, and child in the United States). Some argue that if the S&Ls had been required to report their investments at market value instead of cost, large losses would have been reported earlier, which would have signaled regulators to close those S&Ls and, therefore, minimize the losses to U.S. taxpayers.

Explain how reported accounting numbers might affect an individual's perceptions and actions. Cite two examples.

Instructions

Comment on the appropriateness of this viewpoint.

CA1-5 (AICPA's Role in Rule-Making) One of the major groups involved in the standard-setting process is the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Initially it was the primary organization that established accounting principles in the United States. Subsequently it relinquished its power to the FASB.

Instructions

Identify the two committees of the AICPA that established accounting principles prior to the establishment of the FASB.

Speculate as to why these two organizations failed. In your answer, identify steps the FASB has taken to avoid failure.

What is the present role of the AICPA in the rule-making environment?

CA1-6 (FASB Role in Rule-Making) A press release announcing the appointment of the trustees of the new Financial Accounting Foundation stated that the Financial Accounting Standards Board (to be appointed by the trustees) "... will become the established authority for setting accounting principles under which corporations report to the shareholders and others" (AICPA news release July 20, 1972).

Instructions

Identify the sponsoring organization of the FASB and the process by which the FASB arrives at a decision and issues an accounting standard.

Indicate the major types of pronouncements issued by the FASB and the purposes of each of these pronouncements.

Instructions

The Committee on Accounting Procedure of the AICPA was established in the mid- to late 1930s and functioned until 1959, at which time the Accounting Principles Board came into existence. In 1973, the Financial Accounting Standards Board was formed and the APB went out of existence. Do the reasons these groups were formed, their methods of operation while in existence, and the reasons for the demise of the first two indicate an increasing politicization (as the term is used in the broad sense) of accounting standard-setting? Explain your answer by indicating how the CAP, the APB, and the FASB operated or operate. Cite specific developments that tend to support your answer.

What arguments can be raised to support the "politicization" of accounting rule-making?

What arguments can be raised against the "politicization" of accounting rule-making?

(CMA adapted)

CA1-8 (Models for Setting GAAP) Presented below are three models for setting GAAP.

The purely political approach, where national legislative action decrees GAAP.

The private, professional approach, where GAAP is set and enforced by private professional actions only.

The public/private mixed approach, where GAAP is basically set by private-sector bodies that behave as though they were public agencies and whose standards to a great extent are enforced through governmental agencies.

Instructions

Which of these three models best describes standard-setting in the United States? Comment on your answer.

Why do companies, financial analysts, labor unions, industry trade associations, and others take such an active interest in standard-setting?

Cite an example of a group other than the FASB that attempts to establish accounting standards. Speculate as to why another group might wish to set its own standards.

Instructions

Presented below is a list of common accounting acronyms. Identify the term for which each acronym stands, and provide a brief definition of each term.

AICPA

CAP

ARB

APB

FAF

FASAC

SOP

GAAP

CPA

FASB

SEC

IASB

CA1-10 (Accounting Organizations and Documents Issued) Presented below are a number of accounting organizations and types of documents they have issued.

Instructions

Match the appropriate document to the organization involved. Note that more than one document may be issued by the same organization. If no document is provided for an organization, write in "0."

Organization

_____ Accounting Standards Executive Committee

_____ Accounting Principles Board

_____ Committee on Accounting Procedure

_____ Financial Accounting Standards Board

Document

Opinions

Practice Bulletins

Accounting Research Bulletins

Financial Accounting Standards

Statements of Position

CA1-11 (Accounting Pronouncements) Standard-setting bodies have issued a number of authoritative pronouncements. A list is provided on the left, below, with a description of these pronouncements on the right.

Instructions

Match the description to the pronouncements.

_____ Staff Positions

_____ Interpretations (of the Financial Accounting Standards Board)

_____ Statement of Financial Accounting Standards

_____ EITF Statements

_____ Opinions

_____ Statement of Financial Accounting

Official pronouncements of the APB.

Sets forth fundamental objectives and concepts that will be used in developing future standards.

Primary document of the FASB that establishes GAAP.

Provides additional guidance on implementing or applying FASB Standards or Interpretations.

Provides guidance on how to account for new and unusual financial transactions that have the potential for creating diversity in financial reporting practices.

Represent extensions or modifications of existing standards.

Answer the following questions.

What, if any, is the ethical issue involved in this case?

Is the financial vice president acting improperly or immorally?

What does Weller have to gain by advocacy of early implementation?

Which stakeholders might be affected by the decision against early implementation?

(CMA adapted)

CA1-13 (Securities and Exchange Commission) The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was created in 1934 and consists of five commissioners and a large professional staff. The SEC professional staff is organized into five divisions and several principal offices. The primary objective of the SEC is to support fair securities markets. The SEC also strives to foster enlightened stockholder participation in corporate decisions of publicly traded companies. The SEC has a significant presence in financial markets, the development of accounting practices, and corporation-shareholder relations, and has the power to exert influence on entities whose actions lie within the scope of its authority.

Instructions

Explain from where the Securities and Exchange Commission receives its authority.

Describe the official role of the Securities and Exchange Commission in the development of financial accounting theory and practices.

Discuss the interrelationship between the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Financial Accounting Standards Board with respect to the development and establishment of financial accounting theory and practices.

(CMA adapted)

CA1-14 (Rule-Making Process) In 1973, the responsibility for developing and issuing rules on accounting practices was given to the Financial Accounting Foundation and, in particular, to an arm of the foundation called the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). The generally accepted accounting principles established by the FASB are enunciated through a publication series entitled Statements of Financial Accounting Standards. These statements are issued periodically, and over 160 have been issued. The statements have a significant influence on the way in which financial statements are prepared by U.S. corporations.

Instructions

Describe the process by which a topic is selected or identified as appropriate for study by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

Once a topic is considered appropriate for consideration by the FASB, a series of steps is followed before a Statement of Financial Accounting Standards is issued. Describe the major steps in the process leading to the issuance of a standard.

Identify at least three other organizations that influence the setting of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

(CMA adapted)

Instructions

Answer the following questions.

What appears to be the ethical issue involved in this case?

Is Troy Normand acting improperly or immorally?

What would you do if you were Troy Normand?

Who are the major stakeholders in this case?

CA1-16 (Economic Consequences) Presented below are comments made in the financial press.

Instructions

Prepare responses to the requirements in each item.

Rep. John Dingell, the ranking Democrat on the House Commerce Committee, threw his support behind the FASB's controversial derivatives accounting standard and encouraged the FASB to adopt the rule promptly. Indicate why a member of Congress might feel obligated to comment on this proposed FASB standard.

In a strongly worded letter to Senator Lauch Faircloth (R-NC) and House Banking Committee Chairman Jim Leach (R-IA), the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) cautioned against government intervention in the accounting standard-setting process, warning that it had the potential of jeopardizing U.S. capital markets. Explain how government intervention could possibly affect capital markets adversely.

Dear Sirs:

The FASB has been struggling with accounting for derivatives and hedging for many years. The FASB has now developed, over the last few weeks, a new approach that it proposes to adopt as a final standard. We understand that the Board intends to adopt this new approach as a final standard without exposing it for public comment and debate, despite the evident complexity of the new approach, the speed with which it has been developed and the significant changes to the exposure draft since it was released more than one year ago. Instead, the Board plans to allow only a brief review by selected parties, limited to issues of operationality and clarity, and would exclude questions as to the merits of the proposed approach.

As the FASB itself has said throughout this process, its mission does not permit it to consider matters that go beyond accounting and reporting considerations. Accordingly, the FASB may not have adequately considered the wide range of concerns that have been expressed about the derivatives and hedging proposal, including concerns related to the potential impact on the capital markets, the weakening of companies' ability to manage risk, and the adverse control implications of implementing costly and complex new rules imposed at the same time as other major initiatives, including the Year 2000 issues and a single European currency. We believe that these crucial issues must be considered, if not by the FASB, then by the Securities and Exchange Commission, other regulatory agencies, or Congress.

We believe it is essential that the FASB solicit all comments in order to identify and address all material issues that may exist before issuing a final standard. We understand the desire to bring this process to a prompt conclusion, but the underlying issues are so important to this nation's businesses, the customers they serve and the economy as a whole that expediency cannot be the dominant consideration. As a result, we urge the FASB to expose its new proposal for public comment, following the established due process procedures that are essential to acceptance of its standards, and providing sufficient time to affected parties to understand and assess the new approach.

We also urge the SEC to study the comments received in order to assess the impact that these proposed rules may have on the capital markets, on companies' risk management practices, and on management and financial controls. These vital public policy matters deserve consideration as part of the Commission's oversight responsibilities.

We believe that these steps are essential if the FASB is to produce the best possible accounting standard while minimizing adverse economic effects and maintaining the competitiveness of U.S. businesses in the international marketplace.

Very truly yours,

(This letter was signed by the chairs of 22 of the largest U.S. companies.)

Instructions

Answer the following questions.

Explain the "due process" procedures followed by the FASB in developing a financial reporting standard.

What is meant by the term "economic consequences" in accounting standard-setting?

What economic consequences arguments are used in this letter?

What do you believe is the main point of the letter?

Why do you believe a copy of this letter was sent by the business community to influential members of the United States Congress?

Beverly Crusher, a new staff accountant, is confused because of the complexities involving accounting standard-setting. Specifically, she is confused by the number of bodies issuing financial reporting standards of one kind or another and the level of authoritative support that can be attached to these reporting standards. Beverly decides that she must review the environment in which accounting standards are set, if she is to increase her understanding of the accounting profession.

Beverly recalls that during her accounting education there was a chapter or two regarding the environment of financial accounting and the development of GAAP. However, she remembers that her instructor placed little emphasis on these chapters.

Instructions

Help Beverly by identifying key organizations involved in accounting rule-making.

Beverly asks for guidance regarding authoritative support. Please assist her by explaining what is meant by authoritative support.

Give Beverly a historical overview of how rule-making has evolved so that she will not feel that she is the only one to be confused.

What authority for compliance with GAAP has existed throughout the history of rule-making?

The following comments were made at an Annual Conference of the Financial Executives Institute (FEI).

There is an irreversible movement towards the harmonization of financial reporting throughout the world. The international capital markets require an end to:

The confusion caused by international companies announcing different results depending on the set of accounting standards applied.

Companies in some countries obtaining unfair commercial advantages from the use of particular national accounting standards.

The complications in negotiating commercial arrangements for international joint ventures caused by different accounting requirements.

The inefficiency of international companies having to understand and use a myriad of different accounting standards depending on the countries in which they operate and the countries in which they raise capital and debt. Executive talent is wasted on keeping up to date with numerous sets of accounting standards and the never-ending changes to them.

The inefficiency of investment managers, bankers, and financial analysts as they seek to compare financial reporting drawn up in accordance with different sets of accounting standards.

Instructions

What is the International Accounting Standards Board?

What stakeholders might benefit from the use of International Accounting Standards?

What do you believe are some of the major obstacles to harmonization?

As a newly enrolled accounting major, you are anxious to better understand accounting institutions and sources of accounting literature. As a first step, you decide to explore the FASB's Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1 (CON 1).

Instructions

Access the FASB Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts at the FASB website (http://www.fasb.org) and respond to the following items. (Provide paragraph citations.) When you have accessed the documents, you can search them using the search tool in your Internet browser.

Find Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1. List the ways to access it on the FASB site.

According to CON 1, "... financial reporting includes not only financial statements but also other means of communicating information." What other means are there of communicating information?

According to CON 1, "... many people base economic decisions on their relationships to and knowledge about business enterprises and thus are potentially interested in the information provided by financial reporting." Indicate some of the users and the information they are most directly concerned with in economic decision making.

[1] AICPA Special Committee on Financial Reporting, "Improving Business Reporting—A Customer Focus," Journal of Accountancy, Supplement (October 1994).

[2] "Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises," Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, November 1978), pars. 5–8.

[3] SFAC No. 1, p. iv. As used here, cash flow means "cash generated and used in operations." The term cash flows also frequently means cash obtained by borrowing and used to repay borrowing, cash used for investments in resources and obtained from the disposal of investments, and cash contributed by or distributed to owners.

[4] Management's fiduciary responsibility is to manage assets with care and trust.

[5] The terms principles and standards are used interchangeably in practice and throughout this textbook.

[6] One writer described the relationship of the FASB and SEC and the development of financial reporting standards using the analogy of a pearl. The pearl (a financial reporting standard) "is formed by the reaction of certain oysters (FASB) to an irritant (the SEC)—usually a grain of sand—that becomes embedded inside the shell. The oyster coats this grain with layers of nacre, and ultimately a pearl is formed. The pearl is a joint result of the irritant (SEC) and oyster (FASB); without both, it cannot be created." John C. Burton, "Government Regulation of Accounting and Information," Journal of Accountancy (June 1982).

[7] The FASB Codification can be accessed at http://asc.fasb.org/home. Prior to the Codification, the profession relied on FASB 162, "The Hierarchy of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles," that defined the meaning of generally accepted accounting principles. In that document, certain documents were deemed more authoritative than others, which led to various levels of GAAP. Fortunately, the Codification does not have different levels of GAAP.

[8] To increase the usefulness of the Codification for public companies, relevant authoritative content issued by the SEC is included in the Codification. In the case of SEC content, an "S" precedes the section number.

[9] FASB board members acknowledged that they undertook many of the Board's projects, such as "Accounting for Contingencies," "Accounting for Pensions," "Statement of Cash Flows," and "Accounting for Derivatives," due to political pressure.

[10] Economic consequences means the impact of accounting reports on the wealth positions of issuers and users of financial information, and the decision-making behavior resulting from that impact. The resulting behavior of these individuals and groups could have detrimental financial effects on the providers of the financial information. See Stephen A. Zeff, "The Rise of 'Economic Consequences'," Journal of Accountancy (December 1978), pp. 56–63. We extend appreciation to Professor Zeff for his insights on this chapter.

[11] Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, H. R. Rep. No. 107-610 (2002).

[12] Leah Townsend, "Internal Control Deficiency Disclosures—Interim Alert," Yellow Card—Interim Trend Alert (April 12, 2005), Glass, Lewis & Co., LLC.