After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Companies have different motivations for investing in securities issued by other companies.[269] One motivation is to earn a high rate of return. For example, companies like Coca-Cola and PepsiCo can receive interest revenue from a debt investment or dividend revenue from an equity investment. In addition, they can realize capital gains on both types of securities. Another motivation for investing (in equity securities) is to secure certain operating or financing arrangements with another company. As in the opening story, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo are able to exercise some control over bottler companies based on their significant (but not controlling) equity investments.

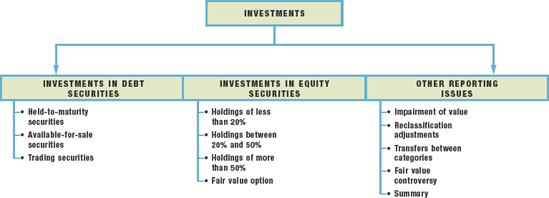

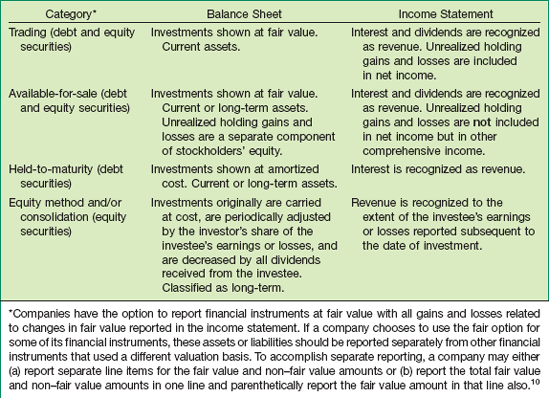

To provide useful information, companies account for investments based on the type of security (debt or equity) and their intent with respect to the investment. As indicated in Illustration 17-1, we organize our study of investments by type of security. Within each section, we explain how the accounting for investments in debt and equity securities varies according to management intent.

Debt securities represent a creditor relationship with another entity. Debt securities include U.S. government securities, municipal securities, corporate bonds, convertible debt, and commercial paper. Trade accounts receivable and loans receivable are not debt securities because they do not meet the definition of a security.

Companies group investments in debt securities into three separate categories for accounting and reporting purposes:

Held-to-maturity: Debt securities that the company has the positive intent and ability to hold to maturity.

Trading: Debt securities bought and held primarily for sale in the near term to generate income on short-term price differences.

Available-for-sale: Debt securities not classified as held-to-maturity or trading securities.

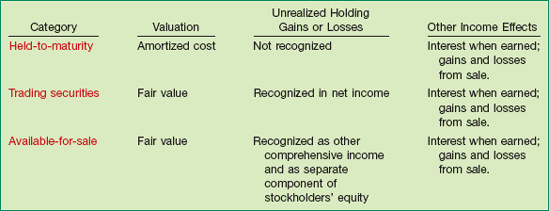

Illustration 17-2 (on page 859) identifies these categories, along with the accounting and reporting treatments required for each.

Amortized cost is the acquisition cost adjusted for the amortization of discount or premium, if appropriate. Fair value is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. [3]

Only debt securities can be classified as held-to-maturity. By definition, equity securities have no maturity date. A company like Starbucks should classify a debt security as held-to-maturity only if it has both (1) the positive intent and (2) the ability to hold those securities to maturity. It should not classify a debt security as held-to-maturity if it intends to hold the security for an indefinite period of time. Likewise, if Starbucks anticipates that a sale may be necessary due to changes in interest rates, foreign currency risk, liquidity needs, or other asset-liability management reasons, it should not classify the security as held-to-maturity.[270]

Companies account for held-to-maturity securities at amortized cost, not fair value. If management intends to hold certain investment securities to maturity and has no plans to sell them, fair values (selling prices) are not relevant for measuring and evaluating the cash flows associated with these securities. Finally, because companies do not adjust held-to-maturity securities to fair value, these securities do not increase the volatility of either reported earnings or reported capital as do trading securities and available-for-sale securities.

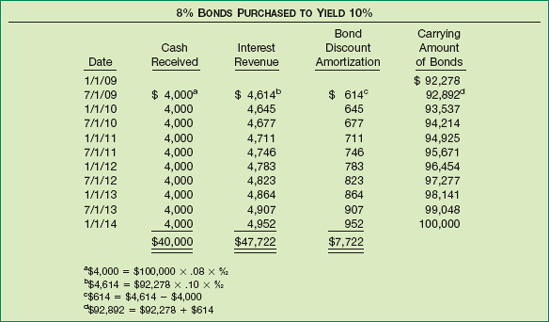

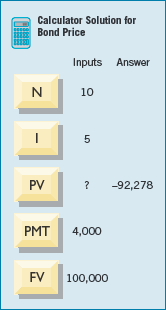

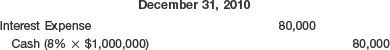

To illustrate the accounting for held-to-maturity debt securities, assume that Robinson Company purchased $100,000 of 8 percent bonds of Evermaster Corporation on January 1, 2009, at a discount, paying $92,278. The bonds mature January 1, 2014 and yield 10%; interest is payable each July 1 and January 1. Robinson records the investment as follows:

Robinson uses a Held-to-Maturity Securities account to indicate the type of debt security purchased.

As indicated in Chapter 14, companies must amortize premium or discount using the effective-interest method unless some other method—such as the straight-line method—yields a similar result. They apply the effective-interest method to bond investments in a way similar to that for bonds payable. To compute interest revenue, companies compute the effective-interest rate or yield at the time of investment and apply that rate to the beginning carrying amount (book value) for each interest period. The investment carrying amount is increased by the amortized discount or decreased by the amortized premium in each period.

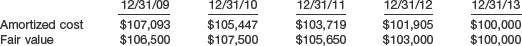

Illustration 17-3 shows the effect of the discount amortization on the interest revenue that Robinson records each period for its investment in Evermaster bonds.

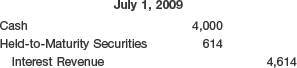

Robinson records the receipt of the first semiannual interest payment on July 1, 2009 (using the data in Illustration 17-3), as follows:

Because Robinson is on a calendar-year basis, it accrues interest and amortizes the discount at December 31, 2009, as follows.

Again, Illustration 17-3 shows the interest and amortization amounts.

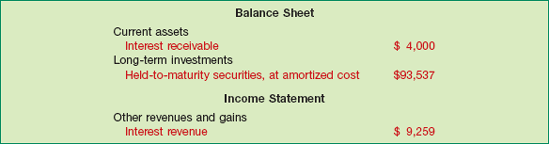

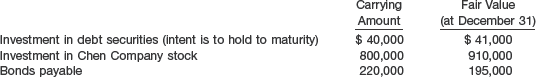

Robinson reports its investment in Evermaster bonds in its December 31, 2009, financial statements, as follows.

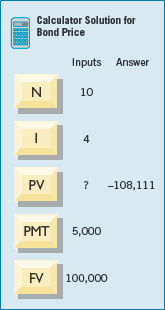

Sometimes a company sells a held-to-maturity debt security so close to its maturity date that a change in the market interest rate would not significantly affect the security's fair value. Such a sale may be considered a sale at maturity and would not call into question the company's original intent to hold the investment to maturity. Let's assume, as an example, that Robinson Company sells its investment in Evermaster bonds on November 1, 2013, at 99¾ plus accrued interest. The discount amortization from July 1, 2013, to November 1, 2013, is $635 (4/6 × $952). Robinson records this discount amortization as follows.

Illustration 17-5 shows the computation of the realized gain on the sale.

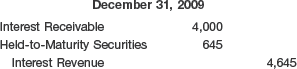

Robinson records the sale of the bonds as:

The credit to Interest Revenue represents accrued interest for four months, for which the purchaser pays cash. The debit to Cash represents the selling price of the bonds plus accrued interest ($99,750 + $2,667). The credit to Held-to-Maturity Securities represents the book value of the bonds on the date of sale. The credit to Gain on Sale of Securities represents the excess of the selling price over the book value of the bonds.

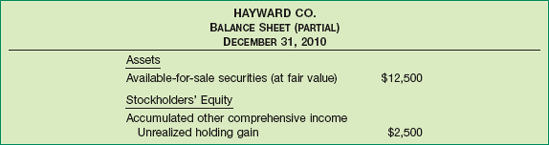

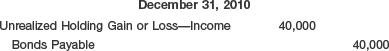

Companies, like Amazon.com, report available-for-sale securities at fair value. It records the unrealized gains and losses related to changes in the fair value of available-for-sale debt securities in an unrealized holding gain or loss account. Amazon adds (subtracts) this amount to other comprehensive income for the period. Other comprehensive income is then added to (subtracted from) accumulated other comprehensive income, which is shown as a separate component of stockholders' equity until realized. Thus, companies report available-for-sale securities at fair value on the balance sheet, but do not report changes in fair value as part of net income until after selling the security. This approach reduces the volatility of net income.

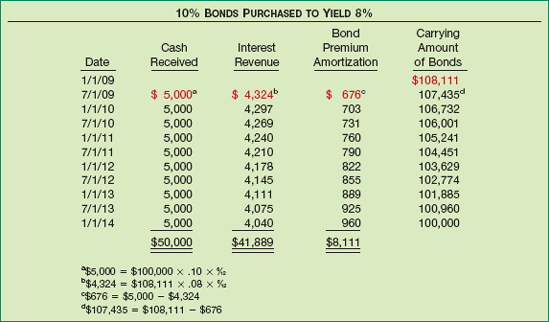

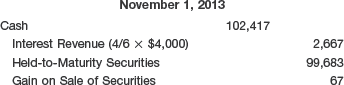

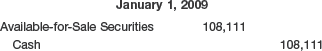

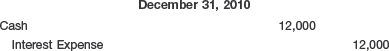

To illustrate the accounting for available-for-sale securities, assume that Graff Corporation purchases $100,000, 10 percent, five-year bonds on January 1, 2009, with interest payable on July 1 and January 1. The bonds sell for $108,111, which results in a bond premium of $8,111 and an effective interest rate of 8 percent.

Graff records the purchase of the bonds as follows.[271]

Illustration 17-6 discloses the effect of the premium amortization on the interest revenue Graff records each period using the effective-interest method.

The entry to record interest revenue on July 1, 2009, is as follows.

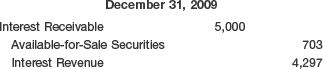

At December 31, 2009, Graff makes the following entry to recognize interest revenue.

As a result, Graff reports revenue for 2009 of $8,621 ($4,324 + $4,297).

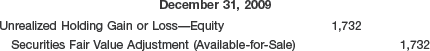

To apply the fair value method to these debt securities, assume that at year-end the fair value of the bonds is $105,000 and that the carrying amount of the investments is $106,732. Comparing this fair value with the carrying amount (amortized cost) of the bonds at December 31, 2009, Graff recognizes an unrealized holding loss of $1,732 ($106,732 − $105,000). It reports this loss as other comprehensive income. Graff makes the following entry.

Graff uses a valuation account instead of crediting the Available-for-Sale Securities account. The use of the Securities Fair Value Adjustment (Available-for-Sale) account enables the company to maintain a record of its amortized cost. Because the adjustment account has a credit balance in this case, Graff subtracts it from the balance of the Available-for-Sale Securities account to determine fair value. Graff reports this fair value amount on the balance sheet. At each reporting date, Graff reports the bonds at fair value with an adjustment to the Unrealized Holding Gain or Loss—Equity account.

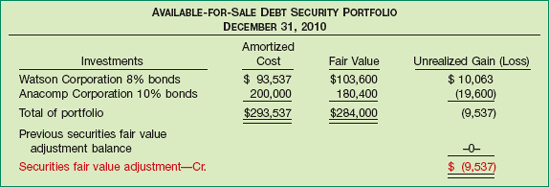

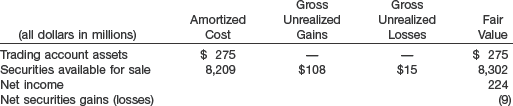

To illustrate the accounting for a portfolio of securities, assume that Webb Corporation has two debt securities classified as available-for-sale. Illustration 17-7 identifies the amortized cost, fair value, and the amount of the unrealized gain or loss.

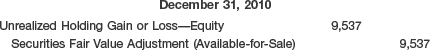

The fair value of Webb's available-for-sale portfolio totals $284,000. The gross unrealized gains are $10,063, and the gross unrealized losses are $19,600, resulting in a net unrealized loss of $9,537. That is, the fair value of available-for-sale securities is $9,537 lower than its amortized cost. Webb makes an adjusting entry to a valuation allowance to record the decrease in value and to record the loss as follows.

Webb reports the unrealized holding loss of $9,537 as other comprehensive income and a reduction of stockholders' equity. Recall that companies exclude from net income any unrealized holding gains and losses related to available-for-sale securities.

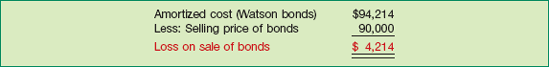

If a company sells bonds carried as investments in available-for-sale securities before the maturity date, it must make entries to remove from the Available-for-Sale Securities account the amortized cost of bonds sold. To illustrate, assume that Webb Corporation sold the Watson bonds (from Illustration 17-7) on July 1, 2011, for $90,000, at which time it had an amortized cost of $94,214. Illustration 17-8 (on page 864) shows the computation of the realized loss.

Webb records the sale of the Watson bonds as follows.

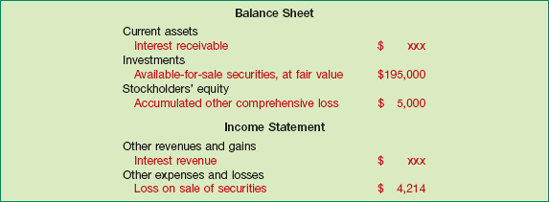

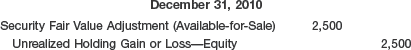

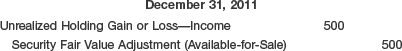

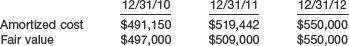

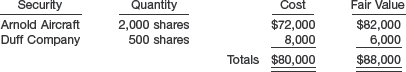

Webb reports this realized loss in the "Other expenses and losses" section of the income statement. Assuming no other purchases and sales of bonds in 2011, Webb on December 31, 2011, prepares the information shown in Illustration 17-9.

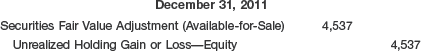

Webb has an unrealized holding loss of $5,000. However, the Securities Fair Value Adjustment account already has a credit balance of $9,537. To reduce the adjustment account balance to $5,000, Webb debits it for $4,537, as follows.

Webb's December 31, 2011, balance sheet and the 2011 income statement include the following items and amounts (the Anacomp bonds are long-term investments but are not intended to be held to maturity).

Some favor including the unrealized holding gain or loss in net income rather than showing it as other comprehensive income.[272] However, some companies, particularly financial institutions, note that recognizing gains and losses on assets, but not liabilities, introduces substantial volatility in net income. They argue that hedges often exist between assets and liabilities so that gains in assets are offset by losses in liabilities, and vice versa. In short, to recognize gains and losses only on the asset side is unfair and not representative of the economic activities of the company.

This argument convinced the FASB. As a result, companies do not include in net income these unrealized gains and losses. [4] However, even this approach solves only some of the problems, because volatility of capital still results. This is of concern to financial institutions because regulators restrict financial institutions' operations based on their level of capital. In addition, companies can still manage their net income by engaging in gains trading (i.e., selling the winners and holding the losers).

In the fall of 2000, Wall Street brokerage firm Morgan Stanley told investors that rumor of big losses in its bond portfolio were "greatly exaggerated." As it turns out, Morgan Stanley also was exaggerating.

As a result, the SEC accused Morgan Stanley of violating securities laws by overstating the value of certain bonds by $75 million. The overvaluations stemmed more from wishful thinking than reality, in violation of generally accepted accounting principles, the SEC said. "In effect, Morgan Stanley valued its positions at the price at which it thought a willing buyer and seller should enter into an exchange, rather than at a price at which a willing buyer and a willing seller would enter into a current exchange," the SEC wrote.

Especially egregious, stated one accounting expert, were the SEC's findings that Morgan Stanley in some instances used its own more optimistic assumptions as a substitute for external pricing sources. "What that is saying is: 'Fair value is what you want the value to be. Pick a number ...' That's especially troublesome."

As indicated in the text, the FASB is assessing what is fair and what isn't when it comes to assigning valuations. Concerns over the issue caught fire after the collapses of Enron Corp. and other energy traders that abused the wide discretion given them under fair value accounting. Investors recently have expressed similar worries about some financial companies, which use internal—and subjectively designed—mathematical models to come up with valuations when market quotes aren't available.

Source: Adapted from Susanne Craig and Jonathan Weil, "SEC Targets Morgan Stanley Values," Wall Street Journal (November 8, 2004), p. C3.

Companies hold trading securities with the intention of selling them in a short period of time. "Trading" in this context means frequent buying and selling. Companies thus use trading securities to generate profits from short-term differences in price. Companies generally hold these securities for less than three months, some for merely days or hours.

Companies report trading securities at fair value, with unrealized holding gains and losses reported as part of net income. Similar to held-to-maturity or available-for-sale investments, they are required to amortize any discount or premium. A holding gain or loss is the net change in the fair value of a security from one period to another, exclusive of dividend or interest revenue recognized but not received. In short, the FASB says to adjust the trading securities to fair value, at each reporting date. In addition, companies report the change in value as part of net income, not other comprehensive income.

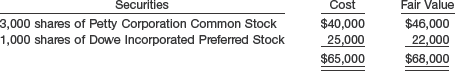

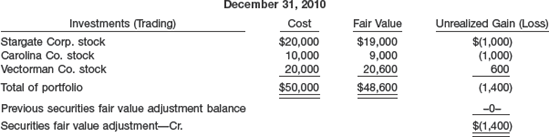

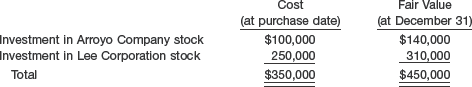

To illustrate, assume that on December 31, 2010, Western Publishing Corporation determined its trading securities portfolio to be as shown in Illustration 17-11. (Assume that 2010 is the first year that Western Publishing held trading securities.) At the date of acquisition, Western Publishing recorded these trading securities at cost, including brokerage commissions and taxes, in the account entitled Trading Securities. This is the first valuation of this recently purchased portfolio.

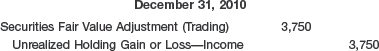

The total cost of Western Publishing's trading portfolio is $314,450. The gross unrealized gains are $12,780 ($7,640 + $5,140), and the gross unrealized losses are $9,030, resulting in a net unrealized gain of $3,750. The fair value of trading securities is $3,750 greater than its cost.

At December 31, Western Publishing makes an adjusting entry to a valuation allowance, referred to as Securities Fair Value Adjustment (Trading), to record the increase in value and to record the unrealized holding gain.

Because the Securities Fair Value Adjustment account balance is a debit, Western Publishing adds it to the cost of the Trading Securities account to arrive at a fair value for the trading securities. Western Publishing reports this fair value amount on the balance sheet.

When securities are actively traded, the FASB believes that the investments should be reported at fair value on the balance sheet. In addition, changes in fair value (unrealized gains and losses) should be reported in income. Such reporting on trading securities provides more relevant information to existing and prospective stockholders.

Equity securities represent ownership interests such as common, preferred, or other capital stock. They also include rights to acquire or dispose of ownership interests at an agreed-upon or determinable price, such as in warrants, rights, and call or put options. Companies do not treat convertible debt securities as equity securities. Nor do they treat as equity securities redeemable preferred stock (which must be redeemed for common stock). The cost of equity securities includes the purchase price of the security plus broker's commissions and other fees incidental to the purchase.

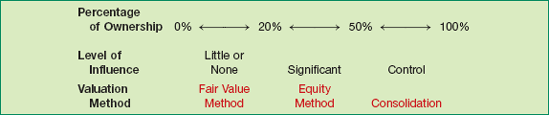

The degree to which one corporation (investor) acquires an interest in the common stock of another corporation (investee) generally determines the accounting treatment for the investment subsequent to acquisition. The classification of such investments depends on the percentage of the investee voting stock that is held by the investor:

Holdings of less than 20 percent (fair value method)—investor has passive interest.

Holdings between 20 percent and 50 percent (equity method)—investor has significant influence.

Holdings of more than 50 percent (consolidated statements)—investor has controlling interest.

Illustration 17-12 lists these levels of interest or influence and the corresponding valuation and reporting method that companies must apply to the investment.

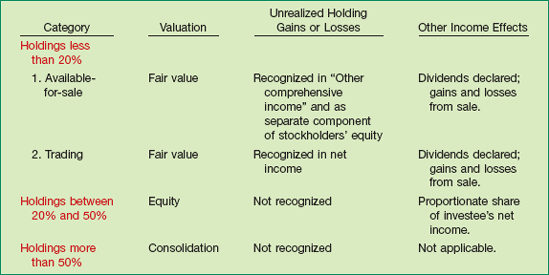

The accounting and reporting for equity securities therefore depend on the level of influence and the type of security involved, as shown in Illustration 17-13.

When an investor has an interest of less than 20 percent, it is presumed that the investor has little or no influence over the investee. In such cases, if market prices are available subsequent to acquisition, the company values and reports the investment using the fair value method.[273] The fair value method requires that companies classify equity securities at acquisition as available-for-sale securities or trading securities. Because equity securities have no maturity date, companies cannot classify them as held-to-maturity.

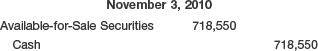

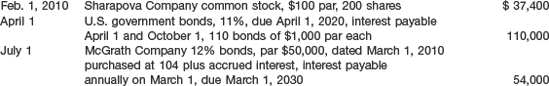

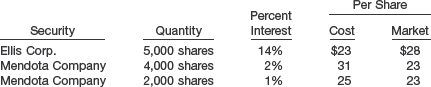

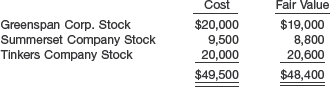

Upon acquisition, companies record available-for-sale securities at cost.[274] To illustrate, assume that on November 3, 2010 Republic Corporation purchased common stock of three companies, each investment representing less than a 20 percent interest.

Republic records these investments as follows.

On December 6, 2010, Republic receives a cash dividend of $4,200 on its investment in the common stock of Campbell Soup Co. It records the cash dividend as follows.

All three of the investee companies reported net income for the year, but only Campbell Soup declared and paid a dividend to Republic. But, recall that when an investor owns less than 20 percent of the common stock of another corporation, it is presumed that the investor has relatively little influence on the investee. As a result, net income earned by the investee is not a proper basis for recognizing income from the investment by the investor. Why? Because the increased net assets resulting from profitable operations may be permanently retained for use in the investee's business. Therefore, the investor earns net income only when the investee declares cash dividends.

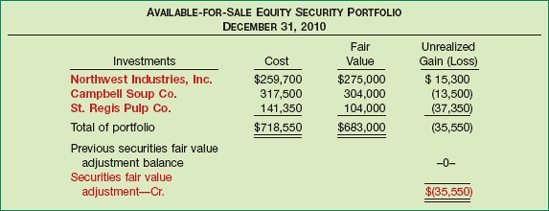

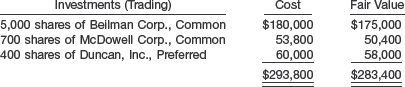

At December 31, 2010, Republic's available-for-sale equity security portfolio has the cost and fair value shown in Illustration 17-14.

Figure 17-14. Computation of Securities Fair Value Adjustment—Available-for-Sale Equity Security Portfolio (2010)

For Republic's available-for-sale equity securities portfolio, the gross unrealized gains are $15,300, and the gross unrealized losses are $50,850 ($13,500 + $37,350), resulting in a net unrealized loss of $35,550. The fair value of the available-for-sale securities portfolio is below cost by $35,550.

As with available-for-sale debt securities, Republic records the net unrealized gains and losses related to changes in the fair value of available-for-sale equity securities in an Unrealized Holding Gain or Loss—Equity account. Republic reports this amount as a part of other comprehensive income and as a component of other accumulated comprehensive income (reported in stockholders' equity) until realized. In this case, Republic prepares an adjusting entry debiting the Unrealized Holding Gain or Loss—Equity account and crediting the Securities Fair Value Adjustment account to record the decrease in fair value and to record the loss as follows.

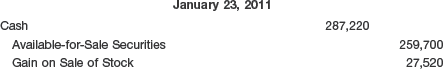

On January 23, 2011, Republic sold all of its Northwest Industries, Inc. common stock receiving net proceeds of $287,220. Illustration 17-15 shows the computation of the realized gain on the sale.

Republic records the sale as follows.

In addition, assume that on February 10, 2011, Republic purchased 20,000 shares of Continental Trucking at a market price of $12.75 per share plus brokerage commissions of $1,850 (total cost, $256,850).

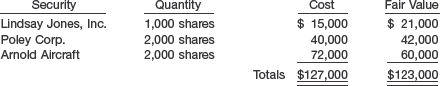

Illustration 17-16 lists Republic's portfolio of available-for-sale securities, as of December 31, 2011.

Figure 17-16. Computation of Securities Fair Value Adjustment—Available-for-Sale Equity Security Portfolio (2011)

At December 31, 2011, the fair value of Republic's available-for-sale equity securities portfolio exceeds cost by $64,250 (unrealized gain). The Securities Fair Value Adjustment account had a credit balance of $35,550 at December 31, 2011. To adjust its December 31, 2011, available-for-sale portfolio to fair value, the company debits the Securities Fair Value Adjustment account for $99,800 ($35,550 + $64,250). Republic records this adjustment as follows.

The accounting entries to record trading equity securities are the same as for available-for-sale equity securities, except for recording the unrealized holding gain or loss. For trading equity securities, companies report the unrealized holding gain or loss as part of net income. Thus, the account titled Unrealized Holding Gain or Loss—Income is used.

An investor corporation may hold an interest of less than 50 percent in an investee corporation and thus not possess legal control. However, as shown in our opening story about Coca-Cola, an investment in voting stock of less than 50 percent can still give Coke (the investor) the ability to exercise significant influence over the operating and financial policies of its bottlers. [5] Significant influence may be indicated in several ways. Examples include representation on the board of directors, participation in policy-making processes, material intercompany transactions, interchange of managerial personnel, or technological dependency.

Another important consideration is the extent of ownership by an investor in relation to the concentration of other shareholdings. To achieve a reasonable degree of uniformity in application of the "significant influence" criterion, the profession concluded that an investment (direct or indirect) of 20 percent or more of the voting stock of an investee should lead to a presumption that in the absence of evidence to the contrary, an investor has the ability to exercise significant influence over an investee.[275]

In instances of "significant influence" (generally an investment of 20 percent or more), the investor must account for the investment using the equity method.

Under the equity method, the investor and the investee acknowledge a substantive economic relationship. The company originally records the investment at the cost of the shares acquired but subsequently adjusts the amount each period for changes in the investee's net assets. That is, the investor's proportionate share of the earnings (losses) of the investee periodically increases (decreases) the investment's carrying amount. All dividends received by the investor from the investee also decrease the investment's carrying amount. The equity method recognizes that investee's earnings increase investee's net assets, and that investee's losses and dividends decrease these net assets.

To illustrate the equity method and compare it with the fair value method, assume that Maxi Company purchases a 20 percent interest in Mini Company. To apply the fair value method in this example, assume that Maxi does not have the ability to exercise significant influence, and classifies the securities as available-for-sale. Where this example applies the equity method, assume that the 20 percent interest permits Maxi to exercise significant influence. Illustration 17-17 shows the entries.

Note that under the fair value method, Maxi reports as revenue only the cash dividends received from Mini. The earning of net income by Mini (the investee) is not considered a proper basis for recognition of income from the investment by Maxi (the investor). Why? Mini may permanently retain in the business any increased net assets resulting from its profitable operation. Therefore, Maxi only earns revenue when it receives dividends from Mini.

Under the equity method, Maxi reports as revenue its share of the net income reported by Mini. Maxi records the cash dividends received from Mini as a decrease in the investment carrying value. As a result, Maxi records its share of the net income of Mini in the year when it is earned. With significant influence, Maxi can ensure that Mini will pay dividends, if desired, on any net asset increases resulting from net income. To wait until receiving a dividend ignores the fact that Maxi is better off if the investee has earned income.

Using dividends as a basis for recognizing income poses an additional problem. For example, assume that the investee reports a net loss. However, the investor exerts influence to force a dividend payment from the investee. In this case, the investor reports income, even though the investee is experiencing a loss. In other words, using dividends as a basis for recognizing income fails to report properly the economics of the situation.

For some companies, equity accounting can be a real pain to the bottom line. For example, Amazon.com, the pioneer of Internet retailing, at one time struggled to turn a profit. Furthermore, some of Amazon's equity investments had resulted in Amazon's earnings performance going from bad to worse. In a recent year, Amazon.com disclosed equity stakes in such companies as Altera International, Basis Technology, Drugstore.com, and Eziba.com. These equity investees reported losses that made Amazon's already bad bottom line even worse, accounting for up to 22 percent of its reported loss in one year alone.

If an investor's share of the investee's losses exceeds the carrying amount of the investment, should the investor recognize additional losses? Ordinarily, the investor should discontinue applying the equity method and not recognize additional losses.

If the investor's potential loss is not limited to the amount of its original investment (by guarantee of the investee's obligations or other commitment to provide further financial support), or if imminent return to profitable operations by the investee appears to be assured, the investor should recognize additional losses. [7]

When one corporation acquires a voting interest of more than 50 percent in another corporation, it is said to have a controlling interest. In such a relationship, the investor corporation is referred to as the parent and the investee corporation as the subsidiary. Companies present the investment in the common stock of the subsidiary as a long-term investment on the separate financial statements of the parent.

When the parent treats the subsidiary as an investment, the parent generally prepares consolidated financial statements. Consolidated financial statements treat the parent and subsidiary corporations as a single economic entity. (Advanced accounting courses extensively discuss the subject of when and how to prepare consolidated financial statements.) Whether or not consolidated financial statements are prepared, the parent company generally accounts for the investment in the subsidiary using the equity method as explained in the previous section of this chapter.

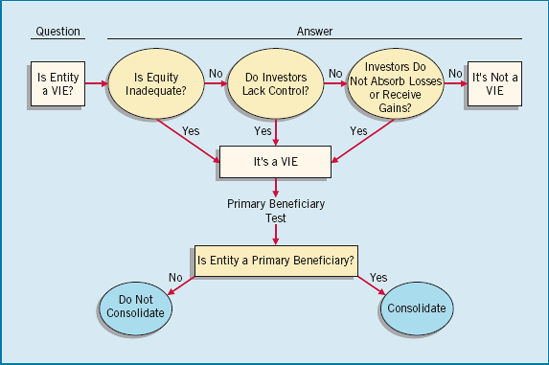

Presently the rules for consolidation seem very straightforward: If a company owns more than 50 percent of another company, it generally should be consolidated. If it owns less than 50 percent, it is generally not consolidated. However the FASB recognizes the artificiality of the present test. Determination of who really has control often relies on factors other than stock ownership.

In fact, specific guidelines force consolidation even though stock ownership is not above 50 percent in certain limited situations. For example, Enron's failure to consolidate three special purpose entities (SPEs) that it effectively controlled led to an overstatement of income of $569 million and overstatement of equity of $1.2 billion. In each of Enron's three SPEs, the GAAP guidelines would have led to consolidation. That is, the following factors indicate that consolidation should have occurred: the majority owner of the special purpose entity (SPE) made only a modest investment; the activities of the SPE primarily benefited Enron; and the substantive risks and rewards related to the assets or debt of the SPE rested directly or indirectly with Enron.

The FASB has issued new guidelines related to SPEs, given all the reporting problems that have surfaced related to SPEs at Enron and other companies. We discuss these new rules in Appendix 17B.

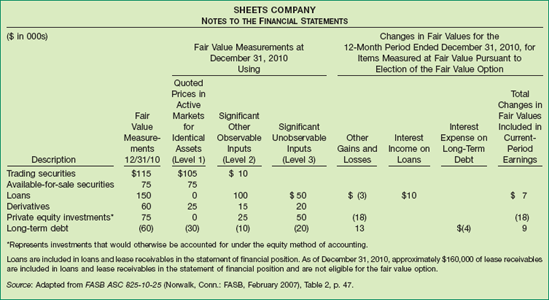

As indicated in earlier chapters, companies have the option to report most financial instruments at fair value, with all gains and losses related to changes in fair value reported in the income statement. This option is applied on an instrument-by-instrument basis. The fair value option is generally available only at the time a company first purchases the financial asset or incurs a financial liability. If a company chooses to use the fair value option, it must measure this instrument at fair value until the company no longer has ownership.

For example, assume that Abbott Laboratories purchased debt securities in 2010 that it classified as held-to-maturity. Abbott does not choose to report this security using the fair value option. In 2011, Abbott buys another held-to-maturity debt security. Abbott decides to report this security using the fair value option. Once it chooses the fair value option for the security bought in 2011, the decision is irrevocable (may not be changed). In addition, Abbott does not have the option to value the held-to-maturity security purchased in 2010 at fair value in 2011 or in subsequent periods.

Many support the use of the fair value option as a step closer to total fair value reporting for financial instruments. They believe this treatment leads to an improvement in financial reporting. Others argue that the fair value option is confusing. A company can choose from period to period whether to use the fair value option for any new investment in a financial instrument. By permitting an instrument-by-instrument approach, companies are able to report some financial instruments at fair value but not others. To illustrate the accounting issues related to the fair value option, we discuss three different situations.

Available-for-sale securities are presently reported at fair value, and any unrealized gains and losses are recorded as part of other comprehensive income. Assume that Hardy Company purchases stock in Fielder Company during 2010 that it classifies as available-for-sale. At December 31, 2010, the cost of this security is $100,000; its fair value at December 31, 2010, is $125,000. If Hardy chooses the fair value option to account for the Fielder Company stock, it makes the following entry at December 31, 2010.

In this situation, Hardy uses an account titled Investment in Fielder Stock to record the change in fair value at December 31. It does not use a Securities Fair Value Adjustment account because the accounting for a fair value option is on an investment-by-investment basis rather than on a portfolio basis. Because Hardy selected the fair value option, the unrealized gain or loss is recorded as part of net income. Hardy must continue to use the fair value method to record this investment until it no longer has ownership of the security.

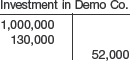

Companies may also use the fair value option for investments that otherwise follow the equity method of accounting. To illustrate, assume that Durham Company holds a 28 percent stake in Suppan Inc. Durham purchased the investment in 2010 for $930,000. At December 31, 2010, the fair value of the investment is $900,000. Durham elects to report the investment in Suppan using the fair value option. The entry to record this investment is as follows.

In contrast to equity method accounting, if the fair value option is chosen, Durham does not have to report its pro rata share of the income or loss from Suppan. In addition, any dividend payments are credited to Dividend Revenue and therefore do not reduce the Investment in Suppan Stock account.

One major advantage of using the fair value option for this type of investment is that it addresses confusion about the equity method of accounting. In other words, what exactly does the one-line consolidation related to the equity method of accounting on the balance sheet tell investors? Many believe it does not provide information about liquidity or solvency, nor does it provide an indication of the worth of the company.

One of the more controversial aspects of the fair value option relates to valuation of a company's own liabilities. Companies may apply the fair value option to their own debt instruments. As a result, changes in the fair value of the debt instrument are included as part of earnings in any given period.

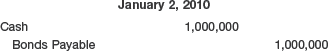

To illustrate, Edmonds Company has issued $500,000 of 6% bonds at face value on May 1, 2010. Edmonds chooses the fair value option for these bonds. At December 31, 2010, the value of the bonds is now $480,000 because interest rates in the market have increased to 8 percent. The value of the debt securities falls because the bond is paying less than market rate for similar securities. Under the fair value option, Edmonds makes the following entry.

As the journal entry indicates, the value of the bonds declined. This decline leads to a reduction in the bond liability and a resulting unrealized holding gain, which is reported as part of net income. The value of Edmonds' debt declined because interest rates increased. In addition, if the creditworthiness of Edmonds Company declines, the value of its debt also declines. That is, Edmonds issued debt at rates reflecting higher creditworthiness. If its creditworthiness declines, its bond investors are receiving a lower rate relative to investors with similar-risk investments. If Edmonds is using the fair value option in this case, it records an unrealized holding gain due to its worsening credit position.

Some question how Edmonds can record a gain when its creditworthiness is becoming worse. As one writer noted, "It seems counter-intuitive." However, the FASB notes that the debtholders' loss is the stockholders' gain. That is, the stockholders' claims on the assets of the company increase when the value of the debtholders declines. In addition, the worsening credit position may indicate that the assets of the company are declining in value as well. Thus, the company may be reporting losses on the asset side which will be offsetting gains on the liability side.

We have identified the basic issues involved in accounting for investments in debt and equity securities. In addition, the following issues relate to both of these types of securities.

Impairment of value.

Reclassification adjustments.

Transfers between categories.

Fair value controversy.

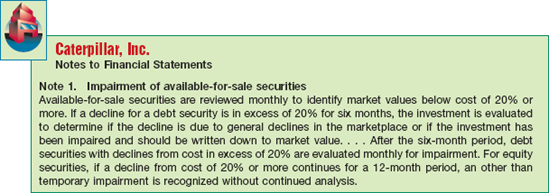

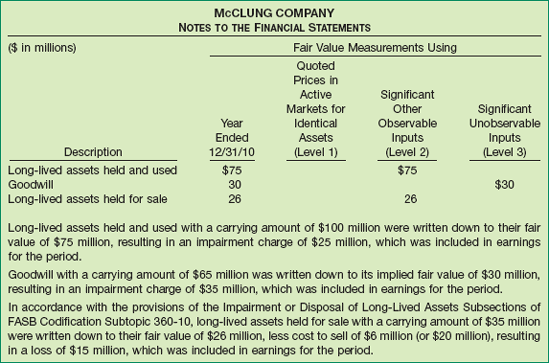

A company should evaluate every investment, at each reporting date, to determine if it has suffered impairment—a loss in value that is other than temporary. For example, if an investee experiences a bankruptcy or a significant liquidity crisis, the investor may suffer a permanent loss. If the decline is judged to be other than temporary, a company writes down the cost basis of the individual security to a new cost basis. The company accounts for the write-down as a realized loss. Therefore, it includes the amount in net income.

For debt securities, a company uses the impairment test to determine whether "it is probable that the investor will be unable to collect all amounts due according to the contractual terms."

For equity securities, the guideline is less precise. Any time realizable value is lower than the carrying amount of the investment, a company must consider an impairment. Factors involved include the length of time and the extent to which the fair value has been less than cost; the financial condition and near-term prospects of the issuer; and the intent and ability of the investor company to retain its investment to allow for any anticipated recovery in fair value.

To illustrate an impairment, assume that Strickler Company holds available-for-sale bond securities with a par value and amortized cost of $1 million. The fair value of these securities is $800,000. Strickler has previously reported an unrealized loss on these securities of $200,000 as part of other comprehensive income. In evaluating the securities, Strickler now determines that it probably will not collect all amounts due. In this case, it reports the unrealized loss of $200,000 as a loss on impairment of $200,000. Strickler includes this amount in income, with the bonds stated at their new cost basis. It records this impairment as follows.

The new cost basis of the investment in debt securities is $800,000. Strickler includes subsequent increases and decreases in the fair value of impaired available-for-sale securities as other comprehensive income.[276]

Companies base impairment for debt and equity securities on a fair value test. This test differs slightly from the impairment test for loans that we discuss in Appendix 7B. The FASB rejected the discounted cash flow alternative for securities because of the availability of market price information.

An example of the criteria used by Caterpillar to assess impairment is provided in Illustration 17-18.

As we indicated in Chapter 4, companies report changes in unrealized holding gains and losses related to available-for-sale securities as part of other comprehensive income. Companies may display the components of other comprehensive income in one of three ways: (1) in a combined statement of income and comprehensive income, (2) in a separate statement of comprehensive income that begins with net income, or (3) in a statement of stockholders' equity.

The reporting of changes in unrealized gains or losses in comprehensive income is straightforward unless a company sells securities during the year. In that case, double counting results when the company reports realized gains or losses as part of net income but also shows the amounts as part of other comprehensive income in the current period or in previous periods.

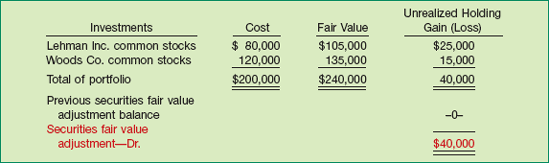

To ensure that gains and losses are not counted twice when a sale occurs, a reclassification adjustment is necessary. To illustrate, assume that Open Company has the following two available-for-sale securities in its portfolio at the end of 2009 (its first year of operations).

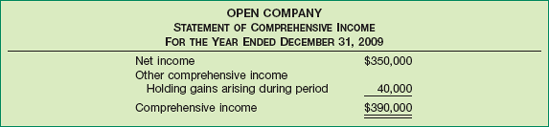

If Open Company reports net income in 2009 of $350,000, it presents a statement of comprehensive income as follows.

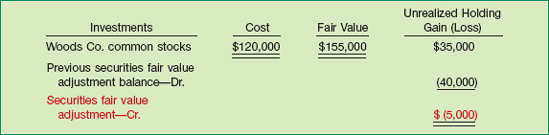

During 2010, Open Company sold the Lehman Inc. common stock for $105,000 and realized a gain on the sale of $25,000 ($105,000 − $80,000). At the end of 2010, the fair value of the Woods Co. common stock increased an additional $20,000, to $155,000. Illustration 17-21 shows the computation of the change in the securities fair value adjustment account.

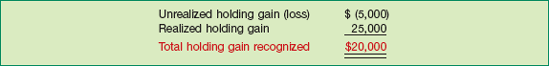

Illustration 17-21 indicates that Open should report an unrealized holding loss of $5,000 in comprehensive income in 2010. In addition, Open realized a gain of $25,000 on the sale of the Lehman common stock. Comprehensive income includes both realized and unrealized components. Therefore, Open recognizes a total holding gain (loss) in 2010 of $20,000, computed as follows.

Open reports net income of $720,000 in 2010, which includes the realized gain on sale of the Lehman securities. Illustration 17-23 shows a statement of comprehensive income for 2010, indicating how Open reported the components of holding gains (losses).

In 2009, Open included the unrealized gain on the Lehman Co. common stock in comprehensive income. In 2010, Open sold the stock. It reported the realized gain in net income, which increased comprehensive income again. To avoid double counting this gain, Open makes a reclassification adjustment to eliminate the realized gain from the computation of comprehensive income in 2010.

A company may display reclassification adjustments on the face of the financial statement in which it reports comprehensive income. Or it may disclose these reclassification adjustments in the notes to the financial statements.

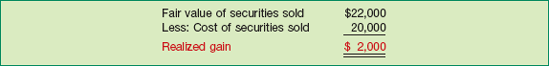

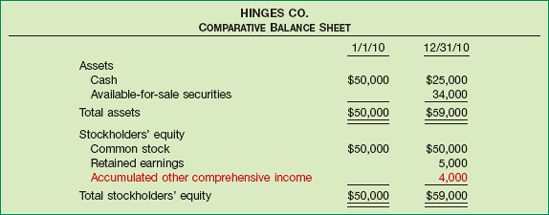

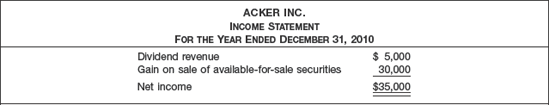

To illustrate the reporting of investment securities and related gain or loss on available-for-sale securities, assume that on January 1, 2010, Hinges Co. had cash and common stock of $50,000.[277] At that date the company had no other asset, liability, or equity balance. On January 2, Hinges purchased for cash $50,000 of equity securities classified as available-for-sale. On June 30, Hinges sold part of the available-for-sale security portfolio, realizing a gain as shown in Illustration 17-24.

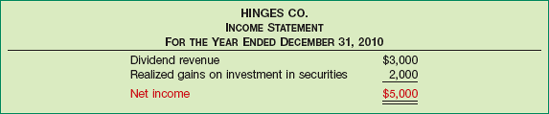

Hinges did not purchase or sell any other securities during 2010. It received $3,000 in dividends during the year. At December 31, 2010, the remaining portfolio is as shown in Illustration 17-25.

Illustration 17-26 shows the company's income statement for 2010.

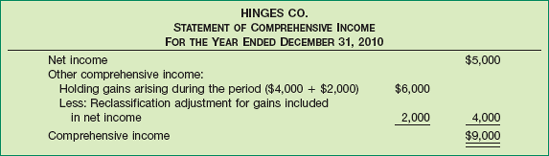

The company reports its change in the unrealized holding gain in a statement of comprehensive income as follows.

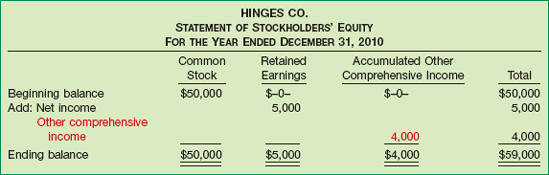

Its statement of stockholders' equity appears in Illustration 17-28.

The comparative balance sheet is shown on the next page in Illustration 17-29.

This example indicates how an unrealized gain or loss on available-for-sale securities affects all the financial statements. Note that a company must disclose the components that comprise accumulated other comprehensive income.

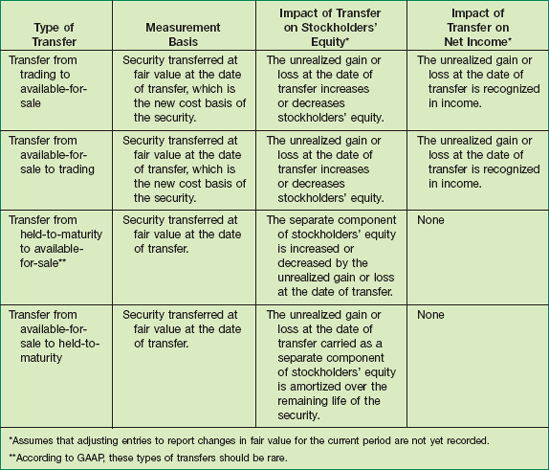

Companies account for transfers between any of the categories at fair value. Thus, if a company transfers available-for-sale securities to held-to-maturity investments, it records the new investment (held-to-maturity) at the date of transfer at fair value in the new category. Similarly, if it transfers held-to-maturity investments to available-for-sale investments, it records the new investments (available-for-sale) at fair value. This fair value rule assures that a company cannot omit recognition of fair value simply by transferring securities to the held-to-maturity category. Illustration 17-30 summarizes the accounting treatment for transfers.

The reporting of investment securities is controversial. Some believe that all securities should be reported at fair value; others believe they all should be stated at amortized cost. Others favor the present approach. In this section we look at some of the major unresolved issues.

Companies classify debt securities as held-to-maturity, available-for-sale, or trading. As a result, companies can report three identical debt securities in three different ways in the financial statements. Some argue such treatment is confusing. Furthermore, the held-to-maturity category relies solely on intent, a subjective evaluation. What is not subjective is the fair value of the debt instrument. In other words, the three classifications are subjective, resulting in arbitrary classifications.

Companies can classify certain debt securities as held-to-maturity and therefore report them at amortized cost. Companies can classify other debt and equity securities as available-for-sale and report them at fair value with the unrealized gain or loss reported as other comprehensive income. In either case, a company can become involved in "gains trading" (also referred to as "cherry picking," "snacking," or "sell the best and keep the rest"). In gains trading, companies sell their "winners," reporting the gains in income, and hold on to the losers.

Many argue that if companies report investment securities at fair value, they also should report liabilities at fair value. Why? By recognizing changes in value on only one side of the balance sheet (the asset side), a high degree of volatility can occur in the income and stockholders' equity amounts. Further, financial institutions are involved in asset and liability management (not just asset management). Viewing only one side may lead managers to make uneconomic decisions as a result of the accounting.

Both the IASB and the FASB believe that fair value information for financial assets and financial liabilities provides more useful and relevant information than a cost-based system. The Boards take this position because fair value reflects the current cash equivalent of the financial instrument rather that the cost of a past transaction. As a consequence, only fair value provides an understanding of the current worth of the investment.

Companies must report fair values for some types of financial instruments. In addition, they have the option to record fair values for any of their financial instruments. How many companies will choose this fair value option? We are hopeful that many companies will select this option; we believe that the information provided by fair value reporting for financial instruments is useful and more understandable to financial statement users.

Illustration 17-31 summarizes the major debt and equity securities and their reporting treatment.

As indicated in the last two sections, the level of disclosure for investment securities is extensive. How to account for investment securities is a particularly sensitive area, given the large amounts of equity investments involved. And presently companies report investments in equity securities at cost, equity, fair value, and full consolidation, depending on the circumstances. As a recent SEC study noted, "there are so many different accounting treatments for investments that it raises the question of whether they are all needed."

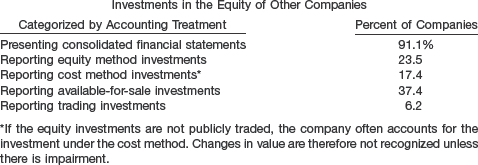

Presented below is an estimate of the percentage of companies on the major exchanges that have investments in the equity of other entities.

As the table indicates, many companies have equity investments of some type. These investments can be substantial. For example, based on the table above, the total amount of equity-method investments appearing on company balance sheets is approximately $403 billion, and the amount shown in the income statements in any one year for all companies is approximately $38 billion.

Source: "Report and Recommendations Pursuant to Section 401(c) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 on Arrangements with Off-Balance Sheet Implications, Special Purpose Entities, and Transparency of Filings by Issuers," United States Securities and Exchange Commission—Office of Chief Accountant, Office of Economic Analyses, Division of Corporation Finance (June 2005), pp. 36–39.

The accounting for investment securities is discussed in IAS 27 ("Consolidated and Separate Financial Statements"), IAS 28 ("Accounting for Investments in Associates"), and IAS 39 ("Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement"). The accounting and reporting under iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are for the most part very similar, although the criteria used to determine the accounting is often different.

The accounting for trading, available-for-sale, and held-to-maturity securities is essentially the same between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP.

Gains and losses related to available-for-sale securities are reported in other comprehensive income under U.S. GAAP. Under iGAAP, these gains and losses are reported directly in equity.

Both iGAAP and U.S. GAAP use the same test to determine whether the equity method of accounting should be used—that is, significant influence with a general guide of over 20 percent ownership. iGAAP uses the term associate investment rather than equity investment to describe its investment under the equity method.

Reclassifications of securities from one category to another generally follow the same accounting under the two GAAP systems. Reclassification in and out of trading securities is prohibited under iGAAP. It is not prohibited under U.S. GAAP, but this type of reclassification should be rare.

Under iGAAP, both the investor and an associate company should follow the same accounting policies. As a result, in order to prepare financial information, adjustments are made to the associate's policies to conform to the investor's books.

The basis for consolidation under iGAAP is control. Under U.S. GAAP, a bipolar approach is used, which is a risk-and-reward model (often referred to as a variable-entity approach) and a voting-interest approach. However, under both systems, for consolidation to occur, the investor company must generally own 50 percent of another company.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are similar in the accounting for the fair value option. That is, the selection to use the fair value method must be made at initial recognition, the selection is irrevocable, and gains and losses related to fair value changes are reported as part of income. The differences relate to disclosures and scope exceptions.

U.S. GAAP does not permit the reversal of an impairment charge related to available-for-sale debt and equity investments. iGAAP follows the same approach for available-for-sale equity investments but permits reversal for available-for-sale debt securities and held-to-maturity securities.

The following example illustrates the accounting for investment impairments under iGAAP. Belerus Company has an available-for-sale investment in the 8 percent, 10-year bonds of Wimbledon Company. The investment has a carrying value of 2,300,000 euros at December 31, 2010. Early in January 2011, Belerus learns that Wimbledon has lost a major customer. As a result, Belerus determines that this investment is impaired and now has a fair value of 1,500,000 euros. Belerus makes the following entry to record the impairment.

Early in 2012, Wimbledon secures several new customers, and its prospects have improved considerably. Belerus determines the fair value of its investment is now 2,000,000 euros and makes the following entry under iGAAP.

Under U.S. GAAP, Belerus is prohibited from recording the recovery in value of the impaired investment. That is, once an investment is impaired, the impaired value becomes the new basis for the investment.

As indicated earlier, both the FASB and IASB have indicated that they believe that all financial instruments should be reported at fair value and that changes in fair value should be reported as part of net income. It seems likely as more companies choose the fair value option for financial instruments, we will eventually arrive at fair value measurement for all financial instruments.

Until the early 1970s, most financial managers worked in a cozy, if unthrilling, world. Since then, constant change caused by volatile markets, new technology, and deregulation has increased the risks to businesses. In response, the financial community developed products to manage these risks.

These products—called derivative financial instruments or simply, derivatives—are useful for managing risk. Companies use the fair values or cash flows of these instruments to offset the changes in fair values or cash flows of the at-risk assets. The development of powerful computing and communication technology has aided the growth in derivative use. This technology provides new ways to analyze information about markets as well as the power to process high volumes of payments.

In order to understand derivatives, consider the following examples.

Example 1—Forward Contract. Assume that a company like Dell believes that the price of Google's stock will increase substantially in the next 3 months. Unfortunately, it does not have the cash resources to purchase the stock today. Dell therefore enters into a contract with a broker for delivery of 10,000 shares of Google stock in 3 months at the price of $110 per share.

Dell has entered into a forward contract, a type of derivative. As a result of the contract, Dell has received the right to receive 10,000 shares of Google stock in 3 months. Further, it has an obligation to pay $110 per share at that time. What is the benefit of this derivative contract? Dell can buy Google stock today and take delivery in 3 months. If the price goes up, as it expects, Dell profits. If the price goes down, Dell loses.

Example 2—Option Contract. Now suppose that Dell needs 2 weeks to decide whether to purchase Google stock. It therefore enters into a different type of contract, one that gives it the right to purchase Google stock at its current price any time within the next 2 weeks. As part of the contract, the broker charges $3,000 for holding the contract open for 2 weeks at a set price.

Dell has now entered into an option contract, another type of derivative. As a result of this contract, it has received the right, but not the obligation to purchase this stock. If the price of the Google stock increases in the next 2 weeks, Dell exercises its option. In this case, the cost of the stock is the price of the stock stated in the contract, plus the cost of the option contract. If the price does not increase, Dell does not exercise the contract, but still incurs the cost for the option.

The forward contract and the option contract both involve a future delivery of stock. The value of the contract relies on the underlying asset—the Google stock. Thus, these financial instruments are known as derivatives because they derive their value from values of other assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, or commodities). Or, put another way, their value relates to a market-determined indicator (e.g., stock price, interest rates, or the Standard and Poor's 500 stock composite index).

In this appendix, we discuss the accounting for three different types of derivatives:

Financial forwards or financial futures.

Options.

Swaps.

Whether to protect for changes in interest rates, the weather, stock prices, oil prices, or foreign currencies, derivative contracts help to smooth the fluctuations caused by various types of risks. A company that wants to ensure against certain types of business risks often uses derivative contracts to achieve this objective.[279]

To illustrate, assume that Heartland Ag is a large producer of potatoes for the consumer market. The present price for potatoes is excellent. Unfortunately, Heartland needs two months to harvest its potatoes and deliver them to the market. Because Heartland expects the price of potatoes to drop in the coming months, it signs a forward contract. It agrees to sell its potatoes today at the current market price for delivery in 2 months.

Who would buy this contract? Suppose on the other side of the contract is McDonald's Corporation. McDonald's wants to have potatoes (for French fries) in 2 months and believes that prices will increase. McDonald's is therefore agreeable to accepting delivery in 2 months at current prices. It knows that it will need potatoes in 2 months, and that it can make an acceptable profit at this price level.

In this situation, if the price of potatoes increases before delivery, Heartland loses and McDonald's wins. Conversely, if the price decreases, Heartland wins and McDonald's loses. However, the objective is not to gamble on the outcome. Regardless of which way the price moves, both Heartland and McDonald's have received a price at which they obtain an acceptable profit. In this case, although Heartland is a producer and McDonald's is a consumer, both companies are hedgers. They both hedge their positions to ensure an acceptable financial result.

Commodity prices are volatile. They depend on weather, crop production, and general economic conditions. For the producer and the consumer to plan effectively, it makes good sense to lock in specific future revenues or costs in order to run their businesses successfully.

In some cases, instead of McDonald's taking a position in the forward contract, a speculator may purchase the contract from Heartland. The speculator bets that the price of potatoes will rise, thereby increasing the value of the forward contract. The speculator, who may be in the market for only a few hours, will then sell the forward contract to another speculator or to a company like McDonald's.

Arbitrageurs also use derivatives. These market players attempt to exploit inefficiencies in markets. They seek to lock in profits by simultaneously entering into transactions in two or more markets. For example, an arbitrageur might trade in a futures contract. At the same time, the arbitrageur will also trade in the commodity underlying the futures contract, hoping to achieve small price gains on the difference between the two. Markets rely on speculators and arbitrageurs to keep the market liquid on a daily basis.

In these illustrations, we explained why Heartland (the producer) and McDonald's (the consumer) would become involved in a derivative contract. Consider other types of situations that companies face.

Airlines, like Delta, Southwest, and United, are affected by changes in the price of jet fuel.

Financial institutions, such as Citigroup, Bankers Trust, and M&I Bank, are involved in borrowing and lending funds that are affected by changes in interest rates.

Multinational corporations, like Cisco Systems, Coca-Cola, and General Electric, are subject to changes in foreign exchange rates.

In fact, most corporations are involved in some form of derivatives transactions. Companies give these reasons (in their annual reports) as to why they use derivatives:

ExxonMobil uses derivatives to hedge its exposure to fluctuations in interest rates, foreign currency exchange rates, and hydrocarbon prices.

Caterpillar uses derivatives to manage foreign currency exchange rates, interest rates, and commodity price exposure.

Johnson & Johnson uses derivatives to manage the impact of interest rate and foreign exchange rate changes on earnings and cash flows.

Many corporations use derivatives extensively and successfully. However, derivatives can be dangerous. All parties involved must understand the risks and rewards associated with these contracts.[280]

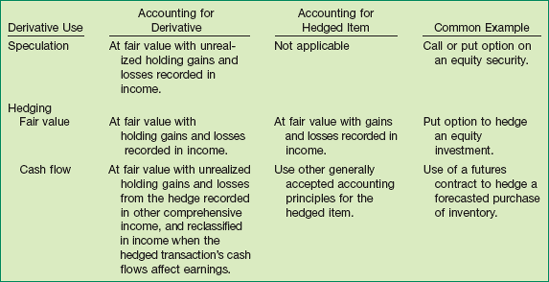

The FASB concluded that derivatives such as forwards and options are assets and liabilities. It also concluded that companies should report them in the balance sheet at fair value[281]. The Board believes that fair value will provide statement users the best information about derivatives. Relying on some other basis of valuation for derivatives, such as historical cost, does not make sense. Why? Because many derivatives have a historical cost of zero. Furthermore, the markets for derivatives, and the assets upon which derivatives' values rely, are well developed. As a result, the Board believes that companies can determine reliable fair value amounts for derivatives.[282]

On the income statement, a company should recognize any unrealized gain or loss in income, if it uses the derivative for speculation purposes. If using the derivative for hedging purposes, the accounting for any gain or loss depends on the type of hedge used. We discuss the accounting for hedged transactions later in the appendix.

In summary, companies follow these guidelines in accounting for derivatives.

Recognize derivatives in the financial statements as assets and liabilities.

Report derivatives at fair value.

Recognize gains and losses resulting from speculation in derivatives immediately in income.

Report gains and losses resulting from hedge transactions differently, depending on the type of hedge.

To illustrate the measurement and reporting of a derivative for speculative purposes, we examine a derivative whose value depends on the market price of Laredo Inc. common stock. A company can realize a gain from the increase in the value of the Laredo shares with the use of a derivative, such as a call option.[283] A call option gives the holder the right, but not the obligation, to buy shares at a preset price. This price is often referred to as the strike price or the exercise price.

For example, assume a company enters into a call option contract with Baird Investment Co., which gives it the option to purchase Laredo stock at $100 per share.[284] If the price of Laredo stock increases above $100, the company can exercise this option and purchase the shares for $100 per share. If Laredo's stock never increases above $100 per share, the call option is worthless.

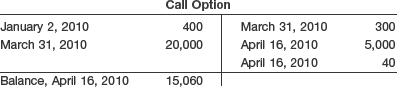

Accounting Entries. To illustrate the accounting for a call option, assume that the company purchases a call option contract on January 2, 2010, when Laredo shares are trading at $100 per share. The contract gives it the option to purchase 1,000 shares (referred to as the notional amount) of Laredo stock at an option price of $100 per share. The option expires on April 30, 2010. The company purchases the call option for $400 and makes the following entry.

This payment is referred to as the option premium. It is generally much less than the cost of purchasing the shares directly. The option premium consists of two amounts: (1) intrinsic value and (2) time value. Illustration 17A-1 shows the formula to compute the option premium.

Intrinsic value is the difference between the market price and the preset strike price at any point in time. It represents the amount realized by the option holder, if exercising the option immediately. On January 2, 2010, the intrinsic value is zero because the market price equals the preset strike price.

Time value refers to the option's value over and above its intrinsic value. Time value reflects the possibility that the option has a fair value greater than zero. How? Because there is some expectation that the price of Laredo shares will increase above the strike price during the option term. As indicated, the time value for the option is $400.[285]

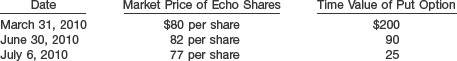

The following additional data are available with respect to the call option.

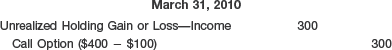

As indicated, on March 31, 2010, the price of Laredo shares increases to $120 per share. The intrinsic value of the call option contract is now $20,000. That is, the company can exercise the call option and purchase 1,000 shares from Baird Investment for $100 per share. It can then sell the shares in the market for $120 per share. This gives the company a gain of $20,000 ($120,000 − $100,000) on the option contract.[286] It records the increase in the intrinsic value of the option as follows.

A market appraisal indicates that the time value of the option at March 31, 2010, is $100[287]. The company records this change in value of the option as follows.

At March 31, 2010, the company reports the call option in its balance sheet at fair value of $20,100.[288] The unrealized holding gain increases net income for the period. The loss on the time value of the option decreases net income.

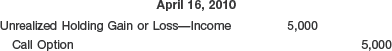

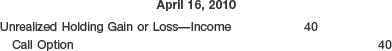

On April 16, 2010, the company settles the option before it expires. To properly record the settlement, it updates the value of the option for the decrease in the intrinsic value of $5,000 ([$20 − $15]) × 1,000) as follows.

The decrease in the time value of the option of $40 ($100 − $60) is recorded as follows.

Thus, at the time of the settlement, the call option's carrying value is as follows.

The company records the settlement of the option contract with Baird as follows.

Illustration 17A-2 summarizes the effects of the call option contract on net income.

The accounting summarized in Illustration 17A-2 is in accord with GAAP. That is, because the call option meets the definition of an asset, the company records it in the balance sheet on March 31, 2010. Furthermore, it reports the call option at fair value, with any gains or losses reported in income.

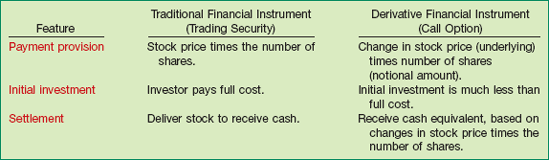

How does a traditional financial instrument differ from a derivative one? A derivative financial instrument has the following three basic characteristics. [10]

The instrument has (1) one or more underlyings and (2) an identified payment provision. An underlying is a specified interest rate, security price, commodity price, index of prices or rates, or other market-related variable. The interaction of the underlying, with the face amount or the number of units specified in the derivative contract (the notional amounts), determines payment. For example, the value of the call option increased in value when the value of the Laredo stock increased. In this case, the underlying is the stock price. To arrive at the payment provision, multiply the change in the stock price by the number of shares (notional amount).

The instrument requires little or no investment at the inception of the contract. To illustrate, the company paid a small premium to purchase the call option—an amount much less than if purchasing the Laredo shares as a direct investment.

The instrument requires or permits net settlement. As indicated in the call option example, the company could realize a profit on the call option without taking possession of the shares. This net settlement feature reduces the transaction costs associated with derivatives.

Illustration 17A-3 summarizes the differences between traditional and derivative financial instruments. Here, we use a trading security for the traditional financial instrument and a call option as an example of a derivative one.

Flexibility in use, and the low-cost features of derivatives relative to traditional financial instruments, explain the popularity of derivatives. An additional use for derivatives is in risk management. For example, companies such as Coca-Cola, ExxonMobil, and General Electric borrow and lend substantial amounts in credit markets. In doing so, they are exposed to significant interest rate risk. That is, they face substantial risk that the fair values or cash flows of interest-sensitive assets or liabilities will change if interest rates increase or decrease. These same companies also have significant international operations. As such, they are also exposed to exchange rate risk—the risk that changes in foreign currency exchange rates will negatively impact the profitability of their international businesses.

Companies can use derivatives to offset the negative impacts of changes in interest rates or foreign currency exchange rates. This use of derivatives is referred to as hedging.

GAAP established accounting and reporting standards for derivative financial instruments used in hedging activities. The FASB allows special accounting for two types of hedges—fair value and cash flow hedges.[289]

As shown in the graph below, use of derivatives has grown steadily in the past several years. In fact, over $450 trillion (in notional amounts) in derivative contracts were in play at the end of 2007. The primary players in the market for derivatives are large companies and various financial institutions, which continue to find new uses for derivatives for speculation and risk management.

Financial engineers continue to develop new uses for derivatives, many times through the use of increasingly complex webs of transactions, spanning a number of markets. As new uses for derivatives appear, the financial system as a whole can be dramatically affected. As a result, some market-watchers are concerned about the risk that a crisis in one company or sector could bring the entire financial system to its knees.

This concern was illustrated recently when both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (two federally-chartered mortgage companies) indicated problems with their derivative accounting, and both of these companies had to restate their financial results for prior periods. This has led Congress to study whether the concentration of mortgages in these institutions is too high. With so many home buyers dependent on Fannie and Freddie, there is concern that these companies may be too loaded down with debt, which could negatively affect the home mortgage market.

Source: Data from International Swaps and Derivatives Association Market Survey (2007).

In a fair value hedge, a company uses a derivative to hedge (offset) the exposure to changes in the fair value of a recognized asset or liability or of an unrecognized commitment. In a perfectly hedged position, the gain or loss on the fair value of the derivative equals and offsets that of the hedged asset or liability.

Companies commonly use several types of fair value hedges. For example, companies use interest rate swaps to hedge the risk that changes in interest rates will impact the fair value of debt obligations. Or, they use put options to hedge the risk that an equity investment will decline in value.

To illustrate a fair value hedge, assume that on April 1, 2010, Hayward Co. purchases 100 shares of Sonoma stock at a market price of $100 per share. Hayward does not intend to actively trade this investment. It consequently classifies the Sonoma investment as available-for-sale. Hayward records this available-for-sale investment as follows.

Hayward records available-for-sale securities at fair value on the balance sheet. It reports unrealized gains and losses in equity as part of other comprehensive income[290]. Fortunately for Hayward, the value of the Sonoma shares increases to $125 per share during 2010. Hayward records the gain on this investment as follows.

Illustration 17A-4 indicates how Hayward reports the Sonoma investment in its balance sheet.

While Hayward benefits from an increase in the price of Sonoma shares, it is exposed to the risk that the price of the Sonoma stock will decline. To hedge this risk, Hayward locks in its gain on the Sonoma investment by purchasing a put option on 100 shares of Sonoma stock.

Hayward enters into the put option contract on January 2, 2011, and designates the option as a fair value hedge of the Sonoma investment. This put option (which expires in two years) gives Hayward the option to sell Sonoma shares at a price of $125. Since the exercise price equals the current market price, no entry is necessary at inception of the put option.[291]

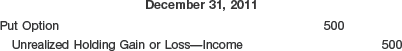

At December 31, 2011, the price of the Sonoma shares has declined to $120 per share. Hayward records the following entry for the Sonoma investment.

Note that upon designation of the hedge, the accounting for the available-for-sale security changes from regular GAAP. That is, Hayward records the unrealized holding loss in income, not in equity. If Hayward had not followed this accounting, a mismatch of gains and losses in the income statement would result. Thus, special accounting for the hedged item (in this case, an available-for-sale security) is necessary in a fair value hedge.

The following journal entry records the increase in value of the put option on Sonoma shares.

The decline in the price of Sonoma shares results in an increase in the fair value of the put option. That is, Hayward could realize a gain on the put option by purchasing 100 shares in the open market for $120 and then exercise the put option, selling the shares for $125. This results in a gain to Hayward of $500 (100 shares × [$125 − $120]).[292]

Illustration 17A-5 indicates how Hayward reports the amounts related to the Sonoma investment and the put option.

The increase in fair value on the option offsets or hedges the decline in value on Hayward's available-for-sale security. By using fair value accounting for both financial instruments, the financial statements reflect the underlying substance of Hayward's net exposure to the risks of holding Sonoma stock. By using fair value accounting for both these financial instruments, the balance sheet reports the amount that Hayward would receive on the investment and the put option contract if Hayward sold and settled them, respectively.

Illustration 17A-6 illustrates the reporting of the effects of the hedging transaction on income for the year ended December 31, 2011.

The income statement indicates that the gain on the put option offsets the loss on the available-for-sale securities[293]. The reporting for these financial instruments, even when they reflect a hedging relationship, illustrates why the FASB argued that fair value accounting provides the most relevant information about financial instruments, including derivatives.

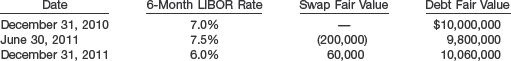

Companies use cash flow hedges to hedge exposures to cash flow risk, which results from the variability in cash flows. The FASB allows special accounting for cash flow hedges. Generally, companies measure and report derivatives at fair value on the balance sheet. They report gains and losses directly in net income. However, companies account for derivatives used in cash flow hedges at fair value on the balance sheet, but they record gains or losses in equity, as part of other comprehensive income.

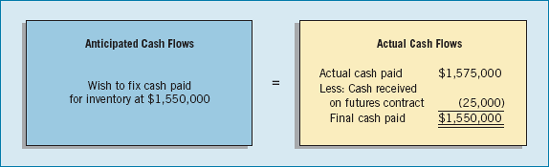

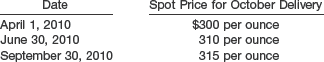

To illustrate, assume that in September 2010 Allied Can Co. anticipates purchasing 1,000 metric tons of aluminum in January 2011. Concerned that prices for aluminum will increase in the next few months, Allied wants to hedge the risk that it might pay higher prices for inventory in January 2011. As a result, Allied enters into an aluminum futures contract.

A futures contract gives the holder the right and the obligation to purchase an asset at a preset price for a specified period of time[294]. In this case, the aluminum futures contract gives Allied the right and the obligation to purchase 1,000 metric tons of aluminum for $1,550 per ton. This contract price is good until the contract expires in January 2011. The underlying for this derivative is the price of aluminum. If the price of aluminum rises above $1,550, the value of the futures contract to Allied increases. Why? Because Allied will be able to purchase the aluminum at the lower price of $1,550 per ton.[295]

Allied enters into the futures contract on September 1, 2010. Assume that the price to be paid today for inventory to be delivered in January—the spot price—equals the contract price. With the two prices equal, the futures contract has no value. Therefore no entry is necessary.

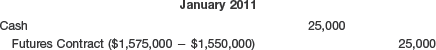

At December 31, 2010, the price for January delivery of aluminum increases to $1,575 per metric ton. Allied makes the following entry to record the increase in the value of the futures contract.

Allied reports the futures contract in the balance sheet as a current asset. It reports the gain on the futures contract as part of other comprehensive income.

Since Allied has not yet purchased and sold the inventory, this gain arises from an anticipated transaction. In this type of transaction, a company accumulates in equity gains or losses on the futures contract as part of other comprehensive income until the period in which it sells the inventory, thereby affecting earnings.

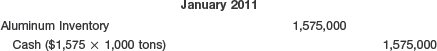

In January 2011, Allied purchases 1,000 metric tons of aluminum for $1,575 and makes the following entry.[296]

At the same time, Allied makes final settlement on the futures contract. It records the following entry.

Through use of the futures contract derivative, Allied fixes the cost of its inventory. The $25,000 futures contract settlement offsets the amount paid to purchase the inventory at the prevailing market price of $1,575,000. The result: net cash outflow of $1,550 per metric ton, as desired. As Illustration 17A-7 shows, Allied has therefore effectively hedged the cash flow for the purchase of inventory.

There are no income effects at this point. Allied accumulates in equity the gain on the futures contract as part of other comprehensive income until the period when it sells the inventory, affecting earnings through cost of goods sold.

For example, assume that Allied processes the aluminum into finished goods (cans). The total cost of the cans (including the aluminum purchases in January 2011) is $1,700,000. Allied sells the cans in July 2011 for $2,000,000, and records this sale as follows.

Since the effect of the anticipated transaction has now affected earnings, Allied makes the following entry related to the hedging transaction.

The gain on the futures contract, which Allied reported as part of other comprehensive income, now reduces cost of goods sold. As a result, the cost of aluminum included in the overall cost of goods sold is $1,550,000. The futures contract has worked as planned. Allied has managed the cash paid for aluminum inventory and the amount of cost of goods sold.

The preceding examples illustrate the basic reporting issues related to the accounting for derivatives. Next, we discuss the following additional issues:

As we indicated at the beginning of this appendix, rapid innovation in the development of complex financial instruments drove efforts toward unifying and improving the accounting standards for derivatives. In recent years, this innovation has led to the development of hybrid securities. These securities have characteristics of both debt and equity. They often combine traditional and derivative financial instruments.

For example, a convertible bond (discussed in Chapter 16) is a hybrid instrument. It consists of two parts: (1) a debt security, referred to as the host security, combined with (2) an option to convert the bond to shares of common stock, the embedded derivative.

To provide consistency in accounting for similar derivatives, a company must account for embedded derivatives similarly to other derivatives. Therefore, to account for an embedded derivative, a company should separate it from the host security and then account for it using the accounting for derivatives. This separation process is referred to as bifurcation[297]. Thus, a company investing in a convertible bond must separate the stock option component of the instrument. It then accounts for the derivative (the stock option) at fair value and the host instrument (the debt) according to GAAP, as if there were no embedded derivative.[298]